Abstract

A transcriptionally active region has been identified in the 5′ flanking region of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus through the evaluation of the activity of putative transcriptional regulators and the role of the region upstream of the gene under specific metabolic circumstances. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays with crude extracts revealed protein complexes that most likely contain TATA box-associated factors. When the TATA element was deleted from the region, binding sites for both DNA binding proteins, such as the small chromatin structure-modeling Sso7d and Sso10b (Alba), and transcription factors, such as the repressor Lrs14, were revealed. To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the substrate-induced expression of the adh gene, the promoter was analyzed for the presence of cis-acting elements recognized by specific transcription factors upon exposure of the cell to benzaldehyde. Progressive dissection of the identified promoter region restricted the analysis to a minimal responsive element (PAL) located immediately upstream of the transcription factor B-responsive element-TATA element, resembling typical bacterial regulatory sequences. A benzaldehyde-activated transcription factor (Bald) that specifically binds to the PAL cis-acting element was also identified. This protein was purified from heparin-fractionated extracts of benzaldehyde-induced cells and was shown to have a molecular mass of ∼16 kDa. The correlation between S. solfataricus adh gene activation and benzaldehyde-inducible occupation of a specific DNA sequence in its promoter suggests that a molecular signaling mechanism is responsible for the switch of the aromatic aldehyde metabolism as a response to environmental changes.

Alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs; EC 1.1.1.1) occur widely in nature and have been found in all living organisms (9). Despite being involved in many different metabolic pathways (23, 25), their role has yet to be clarified.

In the Eucarya, they are commonly encoded by multiple genes and variously expressed tissue specifically or under particular physiological conditions. ADH gene regulation has been demonstrated to be controlled mainly at the transcriptional level; environmental changes affecting the intracellular redox state are the main general factors in the different control mechanisms (30). Induction by oxygen limitation has already been observed in yeasts and bacteria (29, 17), and there is evidence that it can also be linked to carbon source availability during fermentative growth (32). Tissue-specific gene regulation has been studied in detail for insects and mammals (2, 20, 46), in which subcellular compartmentalization contributes to different expression patterns of the isoforms (41). In plants, ADHs can play an important role in defense against different forms of stress, such as in recovery after exposure to toxic drugs and pathogen infection, via transcriptional activation of the corresponding genes (24). For example, a benzyl alcohol dehydrogenase has recently been proposed to be involved in the conversion of benzaldehyde derivatives to the corresponding benzyl alcohols associated either with the incorporation of phenolic defense materials into the cell wall or with the metabolism and disposal of soluble compounds (39). Aryl aldehyde reduction by specific alcohol dehydrogenases is also used by fungi in ligninolysis for the utilization of lignin as a carbon source, namely, by in vivo degradation of natural lignin-derived aldehydes, such veratrylaldehyde and anysaldehyde (28).

The complexity of the functional role of alcohol dehydrogenases is even less exhaustively interpreted among members of the third domain of life, Archaea (45). Detailed investigation of stability, structure, biochemical function, and distribution among different species has been carried out for the euryarchaeaon Pyrococcus furiosus (43) and the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus (3, 15, 16, 21, 37).

As a general rule, these studies have been hampered by the lack of thorough knowledge of fundamental mechanisms controlling cellular processes in thermophilic archaea, although some progress has been achieved due to a combination of biochemistry, genome sequencing (13, 38), and the recent development of promising genetic tools (4, 14, 40). In this context, separate functional studies, as well as the exploitation of genome sequences, have revealed cis- and trans- acting factors that regulate or could modulate transcription in archaea (6, 10). Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the genes involved in specific metabolic pathways are still not completely exploited and are understood mainly for archaeal representatives for which full genetic tools are available (18, 42).

The purpose of this study was to understand the molecular mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene in S. solfataricus (adh) under typical growth conditions, as well as in response to growth in the presence of benzaldehyde, the substrate of the encoded enzyme (16). We identified a functional transcriptionally active sequence in the 5′ flanking region of the gene which is responsive to physiologically relevant DNA binding proteins. The DNA binding proteins were purified and identified. On the basis of the results obtained, it was possible to hypothesize a functional role of the target adh gene in resistance-related aromatic-alcohol metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and preparation of crude extracts.

S.solfataricus cells were grown at 75°C in a DSM (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikoorganismen und Zellkulturen) 182 medium, supplemented with 1 mM benzaldehyde or unsupplemented, under conditions of horizontally shaken cultures in a water bath or in a dry-air incubator where shaking was done by pumping air into a 4-liter fermenter (12). Cell extracts were prepared from cultures harvested at early logarithmic phase, corresponding to an optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.3 or 0.5. Homogenization was done by resuspending the cell pellet in 12 ml of cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and immediately sonicating it six times for 1 min each time with cooling in an ultrasonic liquid processor (Heat System Ultrasonic Inc.) at 20 KHz. The lysate was centrifuged for 30 min at 40,000 × g in an SW41 rotor (Beckman). The cell extracts were concentrated by ultrafiltration through an Amicon ultrafiltration cell (YM1 membrane; 1-kDa cutoff) and, when not used immediately, were frozen and stored at −20°C. The protein concentration was determined as described by Bradford (8), using the Bio-Rad assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Preparation of DNA for DNA binding assays.

Different DNA fragments for mobility shift assays were prepared by endonuclease restriction (ApaI-NcoI, ApaI-EcoRI, EcoRI-NcoI, EcoRI-SspI, and XbaI-SspI) of the 328-bp region upstream of the adh gene (16). The purified fragments were radiolabeled with [α32-P]dATP by Klenow fill in.

The oligonucleotides employed for band shift analysis were as follows: FPAL (5′-TAATGCTATTACGTTATATAACCCCGGG-3′), RPAL (5′-CCCGGGGTTATATAACG-3′), PP1 (5′-TAATGCTATTACCCGGG-3′), RP1 (5′-CCCGGGTAATAGC-3′), PP2 (5′-CGTTATATAACCCCGGG-3′), RP2 5′-CCCGGGTTATAT-3′), 2p1f (5′-TAATGCTATTACTAATGCTATTA-3′), 2p1r (5′-TAATAGCATTAGTAATAGC-3′), 2p2f (5′-GTTATATAACCGTTATATAACCCGGG-3′), 2p2r (5′-GTTATATAACGGTTAT-3′), p1invf (5′-ATTACGATAATCGTTATATAAC-3′), p1invr (5′-GTTATATAACGATTATCG-3′), p2invf (5′-TAATGCTATTACCAATATATTG-3′), and p2invr (5′-CAATATATTGGTAATAGC-3′).

For the preparation of radiolabeled double-stranded probes, reverse oligonucleotides were annealed to an equimolar amount of forward oligonucleotides by slowly cooling them from 95°C to room temperature and were extended using the Klenow enzyme in the presence of [α32-P]dATP. After phenol chloroform extraction, unincorporated oligonucleotides were removed on G-50 nick column chromatography (Pharmacia).

Electrophoretic mobility shifts assays.

Radiolabeled fragments (15,000 cpm) or annealed oligonucleotides (0.2 ng) were used for each binding reaction. A typical reaction mixture contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% glycerol, 4 μg of crude extract or different amounts of purified proteins, and 1 μg of poly(dI-dC). Binding reaction mixtures were preincubated for 10 min at 40°C before the probe was added, and the incubation was continued for 20 min at the same temperature. Glycerol was added to the final 5% concentration, and the samples were loaded on a running 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 1× Tris-borate-EDTA. Electrophoresis was carried out at 100 V in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA running buffer. The gel was dried and exposed to autoradiography.

DNase I footprinting.

The probe for footprinting was prepared by PCR using 32P-labeled 5′-ATGATTACGAATTCGAGCT-3′ (FootR) and 5′ATGAAGGAATTCATGAAC-3′ (FootP) primers designed based on the pUC18 and adh promoter sequences, respectively (the EcoRI site is underlined). FootR was labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The same primer was used to generate a dideoxynucleotide sequence ladder using the Sequenase version 2.0 kit (Amersham). DNase I footprinting was performed as described by Bell and Jackson (7).

Purification of DNA binding activities and native molecular mass determination.

Fractionation was done by loading 3 ml of the cell extracts from benzaldehyde-treated and untreated cells (4 mg/ml) onto a HiTrap heparin-Sepharose column (5 ml; Pharmacia) connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography system and equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)-50 mM KCl. The bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient (60 ml; 50 to 1,000 mM KCl), collected, dialyzed, and concentrated. Active fractions were revealed for their ability to bind to the EcoRI-SspI fragment of the adh promoter and/or to the PAL oligonucleotide and applied to a HiLoad Superdex S-75 column (1.6 by 60 cm; Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)-200 mM KCl and connected to a fast protein liquid chromatography system at a flow rate of 2.0 ml/min. Aliquots of the fractions were analyzed by band shift analysis as described above. Analytical S-75 chromatography (1.0 by 30 cm; Pharmacia) was used to determine the native apparent molecular masses of the proteins using a calibration run under the same conditions with yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (150.0 kDa), bovine serum albumin (69.0 kDa), ovalbumin (44.0 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30.0 kDa), RNase (13.7 kDa), and insulin (5.7 kDa) as molecular mass standards.

Alternatively, the cell extract (48 mg) was applied to a DEAE-Sepharose fast-flow column (7 ml; Pharmacia) equilibrated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). A 50-ml linear gradient (0 to 0.4 M KCl) was used to elute bound proteins. The fractions were assayed for the ability to retard the EcoRI-SspI fragment in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The active fractions were pooled, concentrated, dialyzed, and further purified onto a heparin-Sepharose column as described above.

UV cross-linking.

A chromatographic fraction (10 μg), recovered from heparin-Sepharose chromatography, of extracts from benzaldehyde-treated cells was allowed to bind to radiolabeled PAL double-stranded oligonucleotide (50,000 cpm) in the presence of nonspecific competitor poly(dI-dC) under the same conditions described for the electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The mixture was exposed to UV light (254 nm) for 30 min to cross-link the DNA to the protein before being boiled and loaded on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-15% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried and autoradiographed. After exposure, the same gel was colored with Coomassie blue R250.

DNA affinity chromatography.

Multimerized PAL oligonucleotide was covalently bound to CNBr-activated Sepharose CL4B (Pharmacia), as suggested by the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA bound resin was equilibrated in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8)-50 mM KCl- 10 mM MgCl2- 1 mM DTT- 5% glycerol.

A chromatographic fraction recovered from heparin-Sepharose (300 μg) was incubated for 10 min at 40°C in the presence of 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 8 μg of poly(dI-dC) in a final volume of 1 ml, and the mixture was centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min. The sample was then incubated with the resin for 16 h at 4°C on a rotary shaker. Afterwards, the resin was washed twice before a linear gradient of ionic strength (0.1 to 2.0 M KCl with 0.1 M increases) was applied.

The collected fractions were dialyzed overnight at 4°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) gels, and analyzed by band shift assay.

SDS-PAGE analysis and N-terminal sequence determinations.

All purification steps were analyzed using SDS-PAGE as described by Laemmli (27) on 12.5% polyacrylamide slab gels (Bio-Rad), and the protein bands were stained with either Coomassie brilliant blue (Bio-Rad) or silver stain.

For N-terminal sequences, purified protein samples were subjected to Edman degradation carried out on a pulsed liquid-phase sequencer model 477A (Applied Biosystems) equipped with a 120-A analyzer for the online detection of phenylthiohydantoin amino acids. When the identification of the N-terminal amino acid was hampered, the homogeneous polypeptide was identified by tryptic digestion followed by N-terminal sequencing of the peptides and interrogation of the S. solfataricus P2 genome (38; http://www-archbac.u-psud.fr/projects/sulfolobus/).

RESULTS

Detection of protein-DNA complexes in the promoter region of Ssadh.

A preliminary analysis of the 5′ flanking region of the S.solfataricus alcohol dehydrogenase gene (Ssadh) indicated the presence of cis-acting regulatory sequences typical of archaeal promoters and belonging to the basal transcriptional apparatus, such as the TATA box centered at −27 from the transcriptional start site (16).

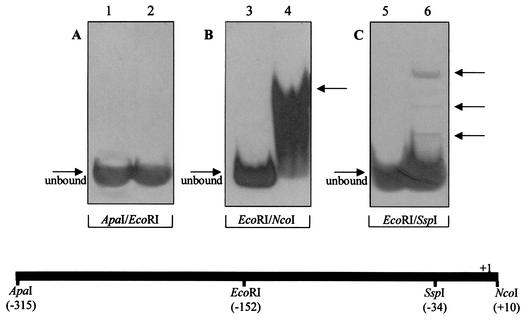

Therefore, in an attempt to precisely locate other transcriptional regulatory sites and to define the boundaries of the adh promoter, the 300-bp sequence upstream of the adh coding region was used as substrate DNA for electrophoretic mobility shift assays using crude extracts of S. solfataricus prepared from cells grown under standard conditions. Two different regions were used in single assays, namely, the restriction subfragments ApaI-EcoRI (at positions −315 to −152 relative to the transcription start site) and EcoRI-NcoI (at positions −152 to +10). The upstream DNA moiety did not show any retardation under the conditions used (Fig. 1A), suggesting the absence of significant regulatory sequences, whereas a complex and continuous shift signal was detected when the second fragment was tested (Fig. 1B); this signal can be attributed to the high-molecular-weight protein complex binding to the minimal promoter sequence. Further dissection of the EcoRI-NcoI region to produce a TATA-less EcoRI-SspI fragment (positions −152 to −34) revealed a much simpler retardation pattern (Fig. 1C), indicating that DNA binding proteins other than basal transcription factors bind specifically in a restricted sequence and thus defining a minimal transcriptionally active upstream region.

FIG. 1.

Detection of binding to the promoter region of Ssadh by proteins in crude extracts of S. solfataricus cells. (A) Binding to the ApaI-EcoRI probe. Lane 1, unbound probe; lane 2, binding of crude extracts. (B) Binding to the EcoRI-NcoI probe. Lane 3, unbound probe; lane 4, binding of crude extracts. The arrow indicates basal complex and complexes 1, 2, and 3. (C) Binding to the EcoRI-SspI probe. Lane 5, unbound probe; lane 6, binding of crude extracts. Arrows indicate complexes 1, 2, and 3 (top to bottom). Below, the positions of restriction sites are numbered relative to the transcription start site.

Purification of the proteins and transcription factors binding to the promoter region of Ssadh.

Two main strategies were adopted for the isolation of proteins different from basal transcription factors and showing affinity with the adh promoter. Crude extracts were fractionated on heparin-Sepharose columns using a KCl salt gradient and tested for the ability to shift the EcoRI-SspI promoter fragment. No activity was revealed in the flowthrough, while two active fractions, eluting in a very narrow range of ionic strengths (at 0.4 [pool 1] and 0.65 [pool 2] M KCl) produced different mobility retardation patterns.

As a further purification step, the two distinct DNA binding activities (pool 1 and pool 2) were isolated by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex S-75 column and eluted with different retention times.

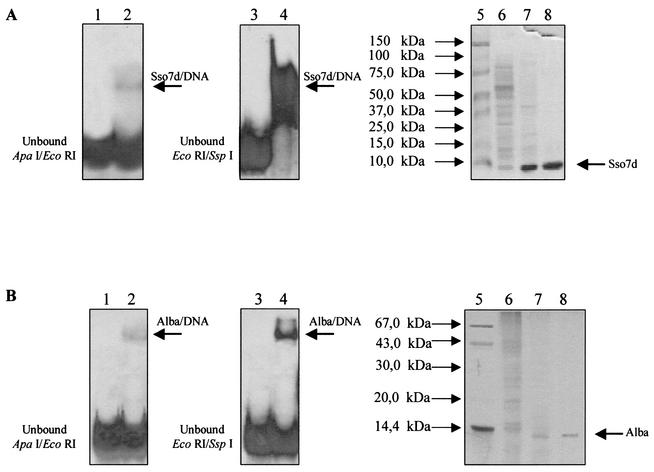

The protein showing binding activity in pool 1 eluted around an apparent molecular mass of ∼7 kDa and was in fact revealed as a unique 7-kDa band when analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (Fig. 2A). For protein identification, the N-terminal amino acid sequence (ATVKFKY) was determined before being used for a search of matching sequences on the S. solfataricus P2 genome by BLAST alignment and recognized as the DNA binding protein Sso7d, already characterized (1, 22, 31, 34).

FIG. 2.

Detection and identification of proteins binding to the adh promoter. (A) Identification of Sso7d. Left, mobility shift assay of ApaI-EcoRI fragment with purified Sso7d; center, mobility shift assay of EcoRI-SspI fragment with purified Sso7d; right, SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane 1, unbound ApaI-EcoRI probe; lanes 2, 4, and 8, fraction from S-75; lane 3, unbound EcoRI-SspI probe; lane 5, molecular mass markers; lane 6, crude extract; lane 7, fraction from heparin-Sepharose eluted at 0.4 M KCl. (B) Identification of Alba by the same assays as in panel A. Lane 1, unbound ApaI-EcoRI probe; lanes 2, 4, and 8, fraction from heparin-Sepharose eluted at 0.75 M KCl; lane 3, unbound EcoRI-SspI probe; lane 5, molecular mass markers; lane 6, crude extract; lane 7, fraction from DEAE eluted at 0.25 M KCl.

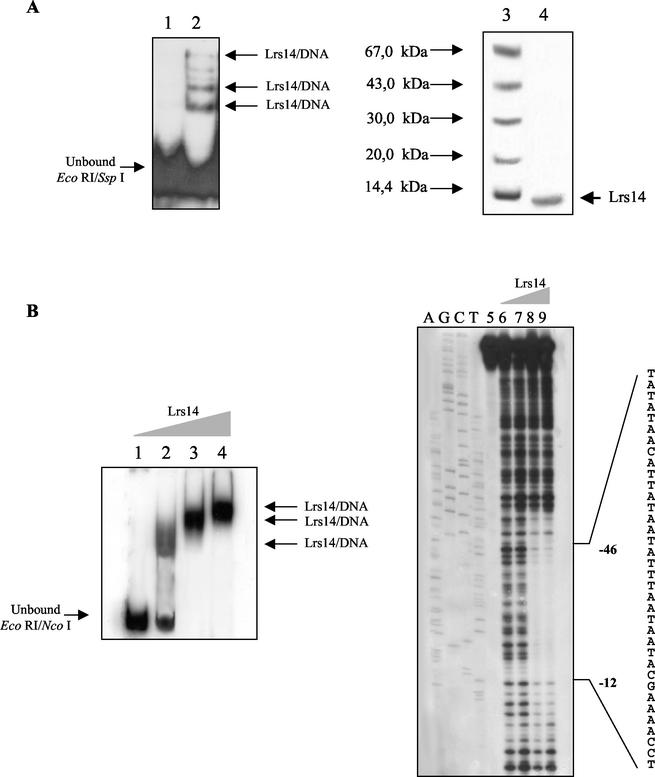

Similarly, the second heparin pool was fractionated on the S-75 column, and an active protein with an apparent native molecular mass of ∼30 kDa was recovered; SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a high-purity-grade protein corresponding to a molecular mass of 14 kDa (Fig. 3A). The N-terminal sequence (MQVENIR) and the research in the S. solfataricus P2 genome data bank identified it as the Lrs14 transcription factor (7, 33). Lrs14 is a recently discovered homodimeric protein related to the bacterial Lrp family of transcriptional regulators. The protein was shown to bind to the promoter region (up to −152) containing or not containing the TATA box, with a mobility shift increasing in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3B), suggesting both the formation of multiple complexes and the presence of multiple binding sites. In fact, Lrs14 gave rise to an extensive DNase I footprint (Fig. 3B) encompassing a core sequence (from −12 to −46) comprising the BRE-TATA element and most of an upstream palindrome sequence located between −40 and −61.

FIG. 3.

Identification and characterization of Lrs14. (A) Purification of Lrs14. Left, mobility shift assay of EcoRI-SspI fragment with purified Lrs14; right, SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane 1, unbound EcoRI-SspI probe; lanes 2 and 4, fraction from S-75; lane 3, molecular mass markers. (B) Characterization of Lrs14. Left, band shift analysis; right, DNase I footprinting. Lane 1, unbound EcoRI-NcoI probe; lanes 2, 3, and 4, Lrs14 (0.5, 1, and 3 μg) incubated with radiolabeled EcoRI-NcoI; lanes A, G, C, and T, sequencing ladders; lane 5, probe (Ssadh promoter); lane 6, probe incubated with DNase I; lanes 7, 8, and 9, probe incubated with Lrs14 (0.2, 0.5, and 1 μg) before the addition of DNase I.

A third protein was identified by a different purification procedure, which consisted of the fractionation of the crude extracts on DEAE-Sepharose followed by a second chromatographic step on heparin-Sepharose.

The protein was purified to homogeneity as assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis, which showed a unique polypeptide of ∼10 kDa (Fig. 2B). Automated amino acid sequence analysis failed, probably because the protein is blocked at its N terminus. Therefore, a step of tryptic digestion, followed by N-terminal microsequencing of the internal peptides, was necessary to produce the sequence VGSQVVTSQDGRQ. Interrogation of the sequences in the S. solfataricus P2 genome identified the DNA binding protein Sso10b, recently renamed Alba (5, 44). As already observed for the crude extract binding, both Sso7d and Alba showed overall very low affinity for the ApaI-EcoRI fragment and significantly stronger (although non-sequence-specific) binding to the TATA-less promoter region immediately downstream (Fig. 2).

An inducible factor binds specifically to a palindromic sequence located upstream of the TATA box.

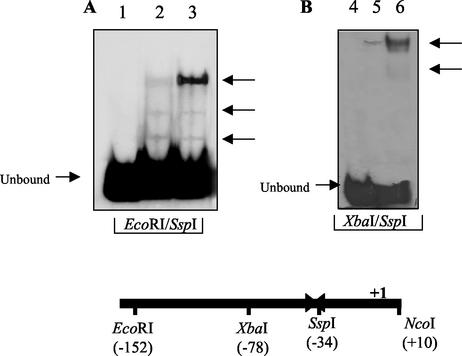

The S. solfataricus adh gene is transcriptionally regulated by benzaldehyde, the substrate of the ADH enzyme, and the maximum inductive effect is observed in cells harvested at early exponential growth phase (A600 = 0.3 OD units) (16). In the framework of a more general project aimed at the assignment of a functional role for the S. solfataricus adh gene to give insight into the definite metabolic role of the encoded enzyme, we investigated in more detail the molecular mechanisms regulating the response to benzaldehyde of adh gene expression. Therefore, we looked for cis-acting elements in the adh promoter interacting with transcriptional regulators specifically present in protein extracts prepared from benzaldehyde-induced cells harvested at an A600 of 0.3 OD units. As a preliminary comparative analysis, the EcoRI-SspI fragment lacking the TATA box element was used in differential band shift assays. Compared to extracts from uninduced cells (Fig. 4A), the appearance of an intense fragment shift in the experiments performed with total proteins from induced cells gave the first evidence of a specific inducible factor. The higher intensity of the specific band shift was even stronger when a shorter 48-bp XbaI-SspI region was used (Fig. 4B), suggesting that one (or more) factor bound tightly and specifically to a very limited sequence in the adh promoter.

FIG. 4.

Mobility shift assay with S. solfataricus cell extracts. (A) Binding to the EcoRI-SspI probe. Lane 1, unbound probe; lane 2, binding of crude extracts; lane 3, binding of crude extracts from benzaldehyde-treated cells. Arrows indicate complexes 1, 2, and 3 (top to bottom). (B) Binding to the XbaI-SspI probe. Lane 4, unbound probe; lane 5, binding of crude extracts; lane 6, binding of crude extracts from benzaldehyde-treated cells. Arrow indicate complexes 1 and 2 (top to bottom).

This region was shown to contain two adjacent double inverted repeats (the same sequence partially recognized by Lrs14), which, due to the similarity to bacterial responsive elements in both position and structure, were good candidates for this specific binding. This hypothesis was verified by testing in independent mobility shift assays a set of double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the same two palindromic sites in the natural sequence (PAL). Figure 5A shows that a site-specific interaction of the protein component identified in the cell extracts was retained with apparently unaltered affinity when tested with the intact PAL sequence. Compared to that caused by extracts of untreated cells, the increased oligonucleotide retardation demonstrated that the binding of a specific protein regulator was markedly induced in response to benzaldehyde. Moreover, the experiments performed with modified versions of the PAL oligonucleotide, containing only the single elements (P1 and P2) or combinations of the two elements in different relative orientations (P1inv and P2inv) or in singular duplications (2P1 and 2P2) (Fig. 5B), demonstrated that the unaltered PAL was the best substrate and that the first palindromic sequence was essential for binding. However, although the second palindrome was unable to be shifted even when duplicated, its presence was considered important, since any modification, such as inversion, strongly reduced the mobility shift of the entire oligonucleotide.

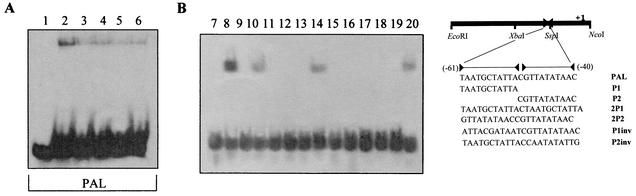

FIG. 5.

Mobility shift assay with S. solfataricus cell extracts of oligonucleotide probes. The assay was performed on one oligonucleotide designed against the region from −61 to −40 (PAL) and on partial subsequences (P1 and P2), duplications (2P1 and 2P2), and inversions of the single motifs (P1inv and P2inv) within the sequence. (A) Binding to the PAL probe. Lane 1, unbound PAL probe; lane 2, binding of crude extracts from benzaldehyde-treated cells; lanes 3, 4, and 5, binding of crude extracts from benzaldehyde-treated cells in the presence of increased amounts of cold specific competitor (200, 400, and 800 ng, respectively); lane 6, binding of cell extracts from untreated cells. (B) Binding to PAL (lanes 7 and 8), P1 (lanes 9 and 10), P2 (lanes 11 and 12), 2P1 (lanes 13 and 14), 2P2 (lanes 15 and 16), P1inv (lanes 17 and 18), and P2inv (lanes 19 and 20) probes. Lanes 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, and 19, unbound probes; lanes 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20, binding of cell extracts from induced cells to the respective probes.

Identification and purification of the inducible factor.

In order to verify that the activity and/or the relative amount of the specific transcription factor increases upon exposure to benzaldehyde, crude extracts from both induced and uninduced S. solfataricus cells were fractionated by heparin-Sepharose chromatography, and active pools were revealed by the presence of a binding activity to the PAL oligonucleotide. Fractions eluting at 0.5 M KCl were found to contain 10-fold-higher binding activity when benzaldehyde was added to the growing cultures (Fig. 6A), whereas those corresponding to the elution of Sso7d, Alba, and Lrs14 were found to contain nearly identical amounts of the specific proteins compared to the same fractions from uninduced cell extracts. Competition experiments demonstrated that interaction with this cis-acting element was very specific, since it could only be competed by the same unlabeled sequence (Fig. 6A).

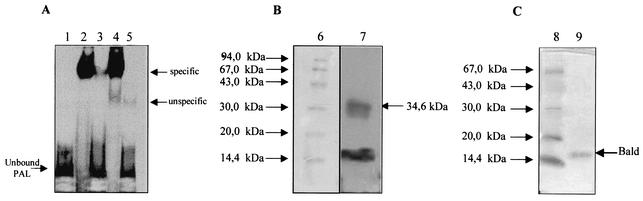

FIG. 6.

Identification and purification of the inducible factor. (A) Band shift analysis. Lane 1, unbound PAL probe; lanes 2 and 3, binding of fractions eluted at 0.5 M KCl from benzaldehyde-induced and uninduced cells; lane 4, binding of benzaldehyde-induced cells incubated with cold nonspecific oligonucleotide (1 μg); lane 5, binding of benzaldehyde-induced cells incubated with cold specific PAL. (B) UV cross-linking. Lane 6, molecular mass markers (Coomassie blue staining); lane 7, PAL protein UV cross-linked complex (autoradiography of SDS-PAGE). (C) SDS-PAGE analysis. Lane 8, molecular mass markers; lane 9, fraction from DNA affinity chromatography.

To further prove the presence in these fractions of a unique factor able to bind to the regulatory element PAL, photoactivated cross-linking was performed. As shown in Fig. 6B, UV cross-linking of PAL sequence to the inducible factor, followed by SDS-PAGE analysis, generated a complex of ∼34 kDa and allowed the identification of a unique binding protein with a calculated molecular mass of ∼16 kDa (obtained by subtracting the oligonucleotide molecular mass of 18 kDa).

This result was confirmed by a further purification step on sequence-specific DNA affinity chromatography in which concatemeric PAL sequences had been covalently bound to the matrix (26). In fact, SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified active protein revealed the same apparent molecular mass of 16 kDa (Fig. 6C).

These results conclusively indicated that this protein, named Bald, whose levels are increased in benzaldehyde-grown cells, specifically interacts with the PAL sequence located in the adh promoter and hence is the protein factor which plays a relevant role in the induction of the adh gene expression by substrate.

DISCUSSION

In order to gain insight into the molecular mechanisms regulating gene transcription in hyperthermophilic archaea, we focused on the expression of an alcohol dehydrogenase gene of the crenarchaeon S. solfataricus. In preliminary studies, a 5′ flanking region of 328 bp was characterized by mapping the transcriptional start site (16) and by testing its capability to drive the heterologous expression of a reporter gene in S. solfataricus (19). In the present work, investigation was carried out to identify the limits of a transcriptionally active sequence in this region, as well as the interacting DNA binding proteins, different from those necessary for basal transcription.

The binding analysis performed on derived DNA subregions with protein extracts fractionated on heparin-Sepharose made it possible to mark out a minimal promoter sequence spanning >162 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays of this sequence allowed the detection and purification of three proteins which had already been well characterized: Sso7d, belonging to a family of nonspecific, small, and abundant DNA binding proteins from different Sulfolobus species (1); the Lrs14 transcription factor, demonstrated to bind upstream to its own open reading frame and to be negatively autoregulated (7, 33); and Sso10b, recently renamed Alba (5, 44), structurally and functionally characterized by its ability to bind double-stranded DNA with no specific consensus and without imposing significant compaction.

Recently, a role for Sso7d in the modeling of DNA in constrained chromatin environments has been hypothesized (34); the binding to the 5′ adh flanking region seems to confirm the ability to model the behavior of DNA in active chromatin regions, such as those endowed with transcriptional activity, which are subjected to greater bending and exposure. In fact, the binding of Sso7d to sequences upstream of the adh minimal promoter which contain the 3′ coding sequence of a putative enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase (annotated as Sso 2535 on the S. solfataricus P2 genome sequence) was clearly much weaker.

Similarly, the sequence-independent binding of Alba to the adh promoter can be explained by assuming a contribution to modulating the DNA structure in this region; the higher affinity found for the sequence (proximal to the TATA box), more active transcriptionally, may be ascribed to the hypothesized role of Alba in transcriptional silencing. It is reasonable to argue that this interaction is necessary to stabilize double-stranded DNAs in sequences with high melting potentials and also to allow displacement by more specific transcriptional regulators.

The purification of the native Lrs14 transcription factor based on its ability to bind to the adh promoter strongly suggests a more direct functional involvement in the global regulation of the adh gene. In fact, adh gene transcription had already been demonstrated to be minimal during the early exponential growth phase (A600 = 0.3 OD units) (16), with a trend opposite to the maximal accumulation of the Lrs14 transcript at similar growth phases (A600 = 0.4 OD units) (33). Lrs14 is known to act as a transcriptional repressor in its own gene autoregulation, and its role as a repressor of adh transcription at early stages of growth was apparently confirmed by the DNase I footprinting analysis performed with the purified protein, which pointed out the extension of protection to the BRE-TATA element and further upstream and downstream, as already demonstrated in similar experiments performed on the Lrs14 promoter (7, 33). Therefore, Lrs14 could be a regulator responsible for a mechanism of repression resembling those of bacteria, keeping adh gene transcription down regulated during the early stages of cell growth, at least under our growth conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the Lrs14 protein, which has been purified directly from its natural source with an activity revealed by functional binding to a target different from its own promoter sequence, thus opening up paths for further investigation of its functional regulatory role.

Our recent studies had already pointed out that adh gene expression is finely regulated at the transcriptional level in the early stage of growth by benzaldehyde, a substrate of the enzyme demonstrated to be toxic for cells at low concentrations (16). In this study, the identification of regulatory factors and their interacting regions was the experimental approach followed to elucidate this specific substrate-mediated activation mechanism. In fact, protein components capable of binding to the adh promoter were shown to be specifically present in the cell extracts of cells exposed to benzaldehyde and to recognize two adjacent double inverted repeats, located immediately upstream of the BRE-TATA element. The possibility that one of the proteins already identified could be specifically overexpressed, and hence could participate in this specific metabolism, was excluded, since the Sso7d, Alba, and Lrs14 proteins were always found in identical amounts in both uninduced and induced cell cultures.

The presence of regulatory sites resembling those of bacteria in the promoters of archaeal genes has already been demonstrated for a few organism models by the use of genetic tools available for in vivo analysis (18, 35, 42).

The recently sequenced genome of S. solfataricus P2 (37) had revealed the presence of 13 putative ADH-encoding genes interspersed on the chromosome and not obviously related except for sequence similarity. The comparative study of all putative ADH-encoding genes of S. solfataricus did not show any conservation of the PAL cis element in their 5′ flanking regions. Therefore, this regulatory site is somehow unique, suggesting that the gene evolved to become specialized in a specific set of functions not shared by other Sulfolobus adh genes.

To date, a few regulators have been studied in thermophilic archaea, mainly by identifying sequences on the genomes, by functional genomics, and by in vitro molecular analyses (6, 11), since the purification of the native products was hampered by their low representation. DNA affinity chromatography, used as a purification strategy, was effective for the isolation of the 16-kDa Bald protein binding to the identified cis-acting regulatory site. However, the serious limitation of low yield in the recovery of the active protein did not allow further characterization. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the purification from its archaeal source of a single putative activator protein which specifically binds to a defined region upstream of its metabolic target gene. Our results suggest that the protein is a key factor involved as a mediator in the environmental signal, triggering adh gene expression in the benzaldehyde induction mechanism. This molecular perspective also strengthens the hypothesis of a specific biological role for the encoded ADH, namely, detoxification by aromatic aldehydes, which is very distinctive compared to the roles of the more common ADHs, which are involved mainly in alcohol fermentation. Interestingly, a recent sequence comparison analysis clustered this archaeal ADH with others from fungi and plants in the same NAD(P)-dependent medium-chain dehydrogenase (MDR) subfamily (36). Therefore, it is possible that the enzyme specificity of S. solfataricus ADH (37) is associated in vivo with the cell defense against phenolic-derived materials, displaying the conversion of benzaldehyde and its derivatives to corresponding benzyl alcohols, which are more soluble, easily metabolized, and excretable (39).

In conclusion, this study revealed that multiple factors and control elements contribute to the fine regulation of adh gene transcription in S. solfataricus and that this system can be used as a model for more general and basic studies of site-specific gene regulation and the interaction of activators and repressors with the basal transcription machinery, as well as regulation by chromatin remodeling.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Raffaele Ronca for technical contributions to Lrs14 characterization.

This work was supported by the European Union (contract QLK3-CT-2000-00649 and contract QLK3-CT-2000-00640).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agback, P., H. Baumann, S. Knapp, R. Ladenstein, and T. Hard. 1998. Architecture of nonspecific protein-DNA interactions in the Sso7d-DNA complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5:579-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amador, A., M. Papaceit, and E. Juan. 2001. Evolutionary change in the structure of the regulatory region that drives tissue and temporally regulated expression of alcohol dehydrogenase gene in Drosophila funebris. Insect Mol. Biol. 10:237-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammendola, S., C. A. Raia, C. Caruso, L. Camardella, S. D'Auria, M. De Rosa, and M. Rossi. 1992. Thermostable NAD+-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase from Sulfolobus solfataricus: gene and protein sequence determination and relationship to other alcohol dehydrogenases. Biochemistry 31:12514-12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aravalli, R. N., and R. A. Garrett. 1997. Shuttle vectors for hyperthermophilic archaea. Extremophiles 1:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, S. D., C. H. Botting, B. N. Wardleworth, S. P. Jackson, and M. F. White. 2002. The interaction of Alba, a conserved archaeal chromatin protein, with Sir2 and its regulation by acetylation. Science 296:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell, S. D., S. S. Cairns, R. L. Robson, and S. P. Jackson. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of an archaeal operon in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell 4:971-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell, S. D., and S. P. Jackson. 2000. Mechanism of autoregulation by an archaeal transcriptional repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:31624-31629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branden, C. I., H. Jornvall, H. Eklund, and B. Furugren. 1975. Alcohol dehydrogenase, p. 103-190. In P. D. Boyer (ed.), The enzymes, 3rd ed., vol. 11. Academic Press, Orlando, Fla.

- 10.Brinkman, A. B., I. Dahlke, J. E. Tuininga, T. Lammers, V. Dumay, E. De Heus, J. H. Lebbink, M. Thomm, W. M. De Vos, and J. Van Der Oost. 2000. An Lrp-like transcriptional regulator from the archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus is negatively autoregulated. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38160-38169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkman, A. B., S. D. Bell, R. J. Lebbink, W. M. De Vos, and J. Van Der Oost. 2002. The Sulfolobus solfataricus Lrp-like protein LysM regulates lysine biosynthesis in response to lysine availability. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29537-29549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock, T. D., K. M. Brock, R. T. Belly, and R. L. Weiss. 1972. Sulfolobus: a new genus of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria living at low pH and high temperature. Arch. Microbiol. 84:54-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bult, C. J., O. White, G. Olsen, L. Zhou, R. D. Fleischmann, et al. 1996. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic Archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii. Science 273:1058-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cannio, R., P. Contursi, M. Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 1998. An autonomously replicating transforming vector for Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Bacteriol. 180:3237-3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannio, R., G. Fiorentino, P. Carpinelli, M. Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 1996. Cloning and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the genes encoding NAD-dependent alcohol deydrogenase from two Sulfolobus species. J. Bacteriol. 178:301-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannio, R., G. Fiorentino, M., Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 1999. The alcohol dehydrogenase gene: distribution among Sulfolobales and regulation in Sulfolobus solfataricus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho, J. Y., and T. W. Jeffries. 1999. Transcriptional control of ADH genes in the xylose-fermenting yeast Pichia stipitis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2363-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen-Kupiec, R., C. Blank, and J. A. Leigh. 1997. Transcriptional regulation in Archaea: in vivo demonstration of a repressor binding site in a methanogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1316-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contursi, P., R. Cannio, S. Prato, G. Fiorentino, M. Rossi, and S. Bartolucci. 2003. Development of a genetic system for hyperthermophilic Archaea: expression of a moderate thermophilic bacterial alcohol dehydrogenase gene in Sulfolobus solfataricus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 218:115-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edenberg, H. J. 2000. Regulation of the mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 64:295-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esposito, L., F. Sica, C. A. Raia, A. Giordano, M. Rossi, L. Mazzarella, and A. Zagari. 2002. Crystal structure of the alcohol dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus at 1.85 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 318:463-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guagliardi, A., L. Cerchia, M. Moracci, and M. Rossi. 2000. The chromosomal protein Sso7d of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus rescues aggregated proteins in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 275:31813-31818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hjelmqvist, L., J. Shafqat, A. R. Siddiqi, and H. Jornvall. 1996. Linking of isozyme and class variability patterns in the emergence of novel alcohol dehydrogenase functions. Characterization of isozymes in Uromastix hardwickii. Eur. J. Biochem. 236:563-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoeren, F. U., R. Dolferus, Y. Wu, W. J. Peacock, and E. S. Dennis. 1998. Evidence for a role for AtMYB2 in the induction of the Arabidopsis alcohol dehydrogenase gene (ADH1) at low oxygen. Genetics 149:479-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jornvall, H., J. O. Hoog, and B. Persson. 1999. SDR and MDR: completed genome sequences show these protein families to be large, of old origin, and of complex nature. FEBS Lett. 445:261-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadonaga, T. J., and R. Tjian. 1986. Affinity purification of sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:5889-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larroy, C., M. R. Fernandez, E. Gonzalez, X. Pares, and J. A. Biosca. 2002. Characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae YMR318C (ADH6) gene product as a broad specificity NADPH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase: relevance in aldehyde reduction. Biochem. J. 361:163-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonardo, M. R., P. R. Cunningham, and D. P. Clark. 1993. Anaerobic regulation of adhE gene, encoding the fermentative alcohol dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:870-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardo, M. R., Y. Dailly, and D. P. Clark. 1996. Role of NAD in regulating the adhE gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:6013-6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Garcia, P., S. Knapp, R. Ladenstein, and P. Forterre. 1998. In vitro DNA binding of the archaeal protein Sso7d induces negative supercoiling at temperatures typical for thermophilic growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:2322-2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzoni, C., M. Saliola, and C. Falcone. 1992. Ethanol-induced and glucose-intensive alcohol dehydrogenase activity in the yeast Kluyveromyces lactis. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2279-2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Napoli, A., J. Van der Oost, C. W. Sensen, R. L. Charlebois, M. Rossi, and M. Ciaramella. 1999. An Lrp-like protein of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus which binds to its own promoter. J. Bacteriol. 181:1474-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napoli, A., Y. Zivanovic, C. Bocs, C. Buhler, M. Rossi, P. Forterre, and M. Ciaramella. 2002. DNA bending, compaction and negative supercoiling by the architectural protein Sso7d of Sulfolobus solfataricus. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2656-2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noll, I., S. Muller, and A. Klein. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding the selenium-free [NiFe]-hydrogenase in the Archaeon Methanococcus voltae involves positive and negative control elements. Genetics 152:1335-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordling, E., H. Jornvall, and B. Persson. 2002. Medium-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (MDR). Family characterizations including genome comparisons and active site modeling. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4267-4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raia, C. A., S. D'Auria, and M. Rossi. 1994. NAD+ dependent alcohol dehydrogenase from S. solfataricus: structural and functional features. Biocatalysis 11:143-150. [Google Scholar]

- 38.She, Q., R. K. Singh, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, G. Allard, M. J. Awayez, C. C. Chan-Weiher, I. G. Clausen, B. A. Curtis, A. De Moors, G. Erauso, C. Fletcher, P. M. Gordon, I. Heikamp-de Jong, A. C. Jeffries, C. J. Kozera, N. Medina, X. Peng, H. P. Thi-Ngoc, P. Redder, M. E. Schenk, C. Theriault, N. Tolstrup, R. L. Charlebois, W. F. Doolittle, M. Duguet, T. Gaasterland, R. A. Garrett, M. A. Ragan, C. W. Sensen, and J. Van Der Oost. 2001. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Somssich, I. E., P. Wernert, S. Kiedrowski, and K. Hahlbrock. 1996. Arabidopsis thaliana defense-related protein ELI3 is an aromatic alcohol:NADP(+) oxidoreductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14199-14203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stedman, K. M., C. Schleper, E. Rumpf, and W. Zillig. 1999. Genetic requirements for the function of the archaeal virus SSV1 in Sulfolobus solfataricus: construction and testing of viral shuttle vectors. Genetics 152:1397-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szalai, G., D. Xie, M. Wassenich, M. Veres, J. D. Ceci, M. J. Dewey, A. Molotkov, G. Duester, and M. R. Felder. 2002. Distal and proximal cis-linked sequences are needed for the total expression phenotype of the mouse alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (Adh1) gene. Gene 291:259-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson, D. K., J. R. Palmer, and C. J. Daniels. 1999. Expression and heat-responsive regulation of a TFIIB homologue from the archaeon Haloferax volcanii. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1081-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Der Oost, J., W. G. Voorhorst, S. W. Kengen, A. C. Geerling, V. Wittenhorst, Y. Gueguen, and W. M. De Vos. 2001. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:3062-3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wardleworth, B. N., R. J. Russell, S. D. Bell, G. L. Taylor, and M. F. White. 2002. Structure of Alba: an archaeal chromatin protein modulated by acetylation. EMBO J. 21:4654-4662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woese, C. R., O. Kandler, and M. L. Wheelis. 1990. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4576-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, Y. H., A. V. Wilks, and J. B. Gibson. 1998. A KP element inserted between the two promoters of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene of Drosophila melanogaster differentially affects expression in larvae and adults. Biochem. Genet. 36:363-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]