Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize and characterize nanogel carriers composed of amphiphilic polymers and cationic polyethylenimine for encapsulation and delivery of cytotoxic nucleoside analogs 5′-triphosphates (NTP) into cancer cells.

Methods

Nanogels were synthesized by a novel micellar approach and compared with carriers prepared by the emulsification/evaporation method. Complexes of nanogels with NTP were prepared; particle size and in vitro drug release were characterized. Resistance of the nanogel-encapsulated NTP to enzymatic hydrolysis was analyzed by ion-pair HPLC. Binding to isolated cellular membranes, cellular accumulation and cytotoxicity were compared using breast carcinoma cell lines CL-66, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. In vivo biodistribution of the 3H-labeled NTP encapsulated in different types of nanogels was evaluated in comparison to the injected NTP alone.

Results

Nanogels with a particle size of 100–300 nm in the unloaded form and less than 140 nm in the NTP-loaded form were prepared. An in vitro release of NTP was ≥50% during the first 24 h. Nanogel formulations ensured increased NTP drug stability against enzymatic hydrolysis as compared to the drug alone. Pluronic®-based nanogels NG(F68), NG(F127), NG(P85) and NGM(P123) demonstrated 2–2.5 times enhanced interaction with cellular membranes and association with various cancer cells compared to NG(PEG). Among them NG(F68) and NG(F127) exhibited the lowest cytotoxicity. Injection of nanogel-formulated NTP significantly modulated the drug accumulation in different mouse organs.

Conclusions

Nanogels composed of Pluronic® F68 and P123 were shown to display certain advanced properties compared to NG(PEG) as a drug delivery system for NTP analogs. Formulations of nucleoside analogs in active NTP form with these nanogels will improve the delivery of these cytotoxic drugs to cancer cells and the therapeutic potential of this anti-cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: nanogels, synthesis, breast cancer cells, cellular association, drug release, organ biodistribution

Abbreviations: HLB, hydrophilic-lipophilic balance; PEI, polyethylenimine; NA, nucleoside analogs; NMP, nucleoside 5′-monophosphate; NTP, nucleoside 5′-triphosphates; PEO, poly(ethylene oxide); PPO, poly(propylene oxide); PEI, polyethylenimine; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); CTP, cytidine 5′-triphophate; FBS, fetal bovine serum; MWCO, molecular weight cut-off; CMC, critical micellization concentration

INTRODUCTION

A recent therapeutic strategy in anti-cancer treatment is the application of polymer- based nanosized drug delivery systems, such as micelles, biodegradable nanoparticles, liposomes and microgels (1). These nanocarriers can reduce non-specific systemic toxicity of antiproliferative drugs and allow a significant amount of drug to be delivered into targeted cancer cells. An important step in drug delivery is the interaction of drug carrier with targeted cells followed by drug release from the carrier. Rational design of the nanocarriers can considerably improve this process. Given the growing number of anticancer drugs, nucleoside analogs (NA) remain among the most effective therapeutic agents despite their toxicity and the multitude of drug resistance mechanisms (2). Nucleoside analogs act as antimetabolites that interfere with nucleic acid synthesis and can exert cytotoxic activity either by incorporating into DNA or RNA or by modifying the metabolism of physiological nucleosides. These agents are generally S-phase specific and show an antiproliferative effect in actively dividing cancer cells. These compounds also possess unique drug-targeted cancer cell interactions that help explain their different spectra of activity. The biological activity of NA depends primarily on their ability to be converted by intracellular kinases into the corresponding 5′-mono-, di-, and triphosphates (3). Consequently, the cellular kinases’ substrate specificity restricts the potential biological activity of NA. In addition, the long-term administration of nucleoside-based drugs can result in decreased kinase activity, thus reducing their efficacy, as seen in AZT, where reduced antiviral activity was due to decreased activity of the prerequisite first phosphorylating enzyme (4, 5). Recent progress in understanding NA drug uptake, metabolism, and interaction with cellular targets concludes that the phosphorylation steps are the key factors in their antiproliferative activity and, in turn, strongly depend on nucleoside structure and cellular type.

In principal, the problem of initial cellular phosphorylation of NA could be overcome by the use of nucleoside 5′-monophosphate (NMP) or their derivatives. Unfortunately, NMP are not metabolically stable in vivo, and they are incapable of crossing cellular membranes since their molecules carry a negative charge at physiological pH. To address this challenge, several ‘pronucleotide’ prodrug approaches have been devised. Amino acid phosphoramidates of NMP have shown promise as potential ‘pronucleotides’ on the assumption that these derivatives will be taken up by tumor tissues and converted in vivo to the corresponding NMP (6). Cell extract studies have provided preliminary evidence of bioactivation but this is still a gray area in the research (7). The ‘pronucleotide’ concept can resolve some of the problems associated with intracellular activation of nucleoside analogues, e.g. some derivatives of the 5′-triphophate of antiviral agent AZT showed higher activity and lower toxicity than AZT (8). However, the ‘pronucleotide’ approach does not solve problems associated with intracellular delivery of phosphorylated nucleoside analogues. Cellular uptake of polyanionic phosphorylated NA is usually an ineffective process, making this step decisive for the final drug activity.

One of the ways to enhance drug uptake and bioavailability is an application of efficient drug delivery systems. Recent efforts were directed toward the development of delivery systems similar to liposomes, which can deliver NA or protect their prodrugs against rapid metabolic activation (9). As an example, encapsulation of a series of 4-(N)-acylated prodrugs of gemcitabine in liposomes can be mentioned (10). However, many small water-soluble molecules, such as ara-C, a NA related to gemcitabine, and 5-fluorouridine diffused rapidly through the liposome bilayer, thus limiting the shelf life and clinical usefulness of these liposomal drug formulations (11, 12). These findings strongly suggest the need to develop a new efficient drug delivery system for NA.

Recently, we proposed a novel type of formulation for cytotoxic NA in their active nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (NTP) form based on a nanogel polymeric network composed of branched PEI and polyethylene glycol (PEG)/Pluronic® molecules (13, 14). NTP cause not only termination of chain elongation by DNA polymerases but also induce S-phase specific apoptosis (15). Administration of NTP as a therapeutic agent has several advantages over NA themselves, including bypass of the key cellular phosphorylation step, direct availability of the drug in active form for inhibition of DNA(RNA) polymerases in proliferating cancer cells, and reduced dosage and non-specific toxicity. A major obstacle in administrating NTP systemically is drug instability and rapid degradation in the blood stream. Formulation of NTP with cationic polymer molecules of nanogels can significantly increase drug stability (13, 16). The complex structure can differ by molecular architecture, as well as by lipophilic properties. The nanogel network binds NTP through ionic interactions forming compact particles, where the drug is protected by the polymer envelope from enzymatic activities and interaction with serum proteins. Moreover, NTP-nanogel complexes are neutral or positively charged, so their cellular accumulation can be significantly enhanced following the initial contact with the cellular membrane. An important property of nanogels is the low buoyant density of the drug formulations that enhances their dispersion stability (16). There are a number of advantages of drug-nanogel formulations over other delivery systems, such as PLGA nanoparticles, liposomes and polymer micelles. The drug-nanogel formulations are prepared by simple mixing of the aqueous solution of NTP and the dispersion of cationic nanogels, thus avoiding the complicated procedures of synthesis of nanoparticles in the presence of encapsulating drug or liposome preparation. The labile NTP cannot be formulated into PLGA nanoparticles by in situ polymerization. High drug loading in the drug-nanogel formulations can provide an increased local drug concentration following its delivery to a targeted site, resolving many of the problems associated with development of drug resistance to NA. The drug-nanogel formulations can be lyophilized and stored at room temperature, a major advantage for therapeutic applications. The polymer envelope surrounding the NTP complexed with PEI backbone of nanogels can greatly reduce exposure of the NTP to the degradative biological environment after systemic administration. Efficient accumulation in cancer cells or tumors may be achieved by vectorizing the nanogels with ligands specific to surface determinants on cancer cells. Importantly, the nanogel-encapsulated NTP are able to cross cellular and endosomal membrane barriers because of enhanced interaction with the membrane itself, a property which can be modified by a proper design of nanogels and their polymer composition. Therefore, these nanogel carriers can be a structural basis in the development of drug delivery systems for chemotherapy using cytotoxic NA.

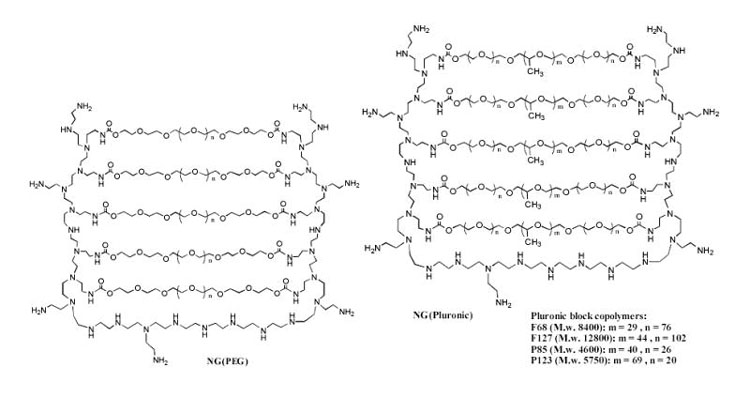

In the present study, we have synthesized and characterized a series of nanogel carriers composed of the cross-linked amphiphilic Pluronic® block copolymers and cationic branched polyethylenimine (PEI) for delivery of 5′-triphosphorylated NA into the cancer cells (Fig. 1). The individual Pluronic® consist of hydrophilic poly(oxyethylene) (PEO) and lipophilic poly(oxypropylene)(PPO) segments of the various length and are characterized by a different hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB). NTP-nanogel complexes were obtained and their membranotropic properties were evaluated in vitro. The present study examines binding of nanogels with the cellular membrane and drug release from the carriers. These findings provide a rationale for quantitative analysis of structure-activity relationships and allow us to identify the prospective candidates for further development of the nanogel-based drug delivery systems.

1.

Schematic presentation of nanogel structure composed of (a) PEG-cl-PEI, or (b) Pluronic®-cl-PEI conjugates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All solvents and reagents, except specially mentioned, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) at the highest purity grade. Pluronic® block copolymers were a generous gift from BASF Corp. (Parsippany, NJ). 3H-Succinimidyl propionate, specific activity 40Ci/mmol, was purchased from ARC, Inc. (St.Louis, MO). BODIPY® FL ATP was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). SpectraPor dialysis membrane tubes with various MW cutoffs were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

Synthesis of Nanogels

Both ends of PEG (MW 4.6 and 8 kDa) and Pluronic® (F127, F68, P85 or P123) were activated by reaction with 10-fold molar excess of 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole in dry acetonitrile (40°C, 2 h). Activated products were purified by dialysis (MWCO 2 kDa) twice for 4 h against 10% ethanol at 4°C. These solutions were concentrated in vacuo and lyophilized. Commercial PEI (MW 25 kDa) was purified by gel-permeation chromatography using Sephacryl S200 column (2.5 x 60 cm) and water as an eluent and a weight diagram was obtained for the content of all fractions. Fractions of PEI with intermediate MW (more than 50% of loaded PEI by weight) were pooled and directly used in nanogel synthesis. Synthesis of nanogels, NG(PEG), NG(F68), NG(F127) and NG(P85), was performed using the ‘emulsification-solvent evaporation’ method as described previously (13, 14).

Another, micellar approach was used to synthesize nanogels NGM(F127), NGM(P85) and NGM(P123). In this method, aqueous 1% (w/v) PEI solution was added dropwise into an equal volume of aqueous 2% solution of the freshly activated Pluronic® under a vigorous stirring to form polymer micelles. The reaction of PEI with activated ends of polymer micelles was continued overnight at 25°C. Finally, the same volume of aqueous 4% solution of the activated PEG was added to the reaction mixture to cross-link the PEI envelope surrounding the polymer micelles. The stirring was continued for another 24 h at 25°C. The formed nanogel dispersions were purified by dialysis (MWCO 50 kDa) twice during 24 h against 10% ethanol containing 0.02% aqueous ammonia at 25°C and lyophilized.

For analysis of the polymer/PEI ratio in nanogels, 5% solutions were prepared in D2O and filtered, and 1H NMR spectra (with integration) were registered at 25°C in the range of 0–6 ppm using the Varian 300 MHz spectrometer. Elemental analysis (M-H-W Laboratories, Phoenix, AZ) was used to measure the total nitrogen content in nanogel preparations.

Rhodamine-Labeled Nanogels

Dispersion of nanogels (10% w/v) in 2 ml of 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer, pH 9, was treated with 1% solution of rhodamine isothiocyanate (0.2 ml) in DMF overnight at 25°C. The rhodamine-labeled nanogels were isolated by gel filtration using NAP-10 columns (GE-Amersham, Parsipany, NJ) in 10% ethanol and lyophilized. Fluorescent spectral characteristics of the rhodamine-labeled nanogels (λex 549 nm and λem 577 nm) were measured in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using a Shimadzu RF5000 spectrofluorimeter. Linear calibration curves for each nanogel were obtained in the range of 1–500 μg/ml.

Tritium-Labeled Nanogels

All 3H-labeled nanogels used in present study were obtained as described earlier (17). Briefly, 10% (w/v) dispersion of nanogels in 1 ml of anhydrous acetonitrile containing 2% (v/v) of triethylamine was treated with a solution of 3H-succinimidyl propionate (100 μCi) in ethyl acetate overnight at 25°C. Organic solvents were removed in the flow of nitrogen, and 3H -labeled nanogels were isolated using NAP-10 column in 10% ethanol. Fractions containing nanogel were collected, analyzed by liquid scintillation counting, and lyophilized. Specific activity of the labeled nanogels was ca. 8 μCi/mg.

Nanogel-Drug Complexes

Nanogel-drug complexes were prepared using cytidine 5′-triphosphate (CTP) as a model nucleoside-based drug. Drug loading was performed by simple mixing of the solution of a sodium salt of CTP with different nanogel dispersions in phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and the N/P ratio (total amino group concentration in nanogel solution to phosphate group concentration) equal to 3. Complexes were allowed to form for at least 30 min. Excess unbound CTP was removed by short dialysis (MWCO 2 kDa, 4 h, 4 °C) , and the obtained formulations were freeze-dried (Formulations A). In the second approach, nanogels were converted into a free amino form by overnight dialysis against 0.02% aqueous ammonia. The nanogel dispersion was concentrated in vacuo, filtered, and redissolved in water. Sodium salt of CTP was dissolved in water and passed through a short column with Dowex 50 × 6 in H+ form to obtain a free acid form of CTP. The column was then washed by water (2 × 15 ml), and the eluate was used directly for titration of nanogel dispersions until pH 7.4. The obtained dispersions of the CTP-loaded nanogels (Formulations B) were freeze-dried. CTP content in the dispersions was then determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm.

Electron Microscopy

Electron-contrasted nanogels were prepared from aqueous dispersions (5 mg mL−1) mixed with 1 mM cupric nitrate in 10 mM tris buffer, pH 7.4, at the molar Cu2+/PEI ratio 10, which is equivalent to about 10% of PEI saturation by Cu2+ cations. Aqueous CTP solution (0.1 M; 5 μl per 1 mg of nanogel) was added 30 min later, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 25°C to obtain nanogel-CTP complexes. Low-molecular weight components were removed during dialysis (MWCO 2,000 Da) against water for 4 h and complexes were freeze-dried. Samples were resuspended by sonication in water (concentration 1%) prior the TEM analysis, placed on the grid and directly investigated using a Philips 410LS transmission electron microscope equipped with an AMT digital imaging system (UNMC Electron Microscopy Core).

Cell Culturing

Human breast carcinoma MCF-7 and MDA-MD-231 cells were obtained from the ATCC (Rockville, MD), and murine breast carcinoma CL-66 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Rakesh Singh (UNMC). Cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with nonessential amino acids, 2 mM of l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml). All culture media were obtained from Gibco (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cancer cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells per well in 96-wells plates or 50,000 cells per well in 24-wells or Bioptech plate for confocal microscopy and allowed to grow overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2 for reattachment.

Interaction of Nanogels with Isolated Cellular Membranes

Crude cellular membranes were isolated according to the procedure of Hamada et al with some modifications (18). Briefly, approximately 2x 108 harvested MCF-7 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and the cell pellet was resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, and 1 mM PMSF; 1 x 107 cells in 1 ml). The swollen cells were disrupted with 20 strokes in a tightly fitting homogenizer and nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 1200x g for 10 min at 4°C. The nuclei-free supernatant was centrifuged at 110,000x g for 1 h at 4°C and the pellet was used as a crude membrane fraction. The membrane fraction was suspended in a hypotonic lysis buffer containing 50% (w/v) glycerol and stored at −80°C. The total protein content in the membranes was determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay.

Binding of 3H-labeled nanogels to isolated cellular membranes was performed as described earlier (13). Briefly, isolated membrane aliquots (1 mg/ml of total protein) were treated with 70μg of the 3H -labeled nanogels and incubated at 37°C for different time intervals (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h). Membranes were separated from nanogels in the samples by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm. The membrane pellet was dissolved in 500 μl PBS, and 10μl of solution was used for the radioactive counting. All measurements were done in triplicate.

In Vitro Drug Release

Nanogel-CTP complexes (Formulations A) were divided into two equal parts with cellular membranes (1mg/ml protein) added to one part. The mixtures were placed into dialysis tubes (MWCO 2 kDa) and dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.4) at 25°C. At each time point, 50 μl-samples were removed, diluted 20-fold, and their UV-absorbance was determined at 260 nm.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

0.1% (w/v) dispersions of nanogel-CTP complexes (Formulations B) were prepared in the Ringer’s solution, pH 8.2. 95μl of each solution was incubated with or without 5 μL (2 units) of alkaline phosphatase at 37º C for 10 min. Samples were analyzed by the ion-pair HPLC using Vydac C18 column (5μm, 0.46 x 15cm) at flow rate of 1 ml/min. Elution with the buffer A: 40 mM KH2PO4, 0.2% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, pH 7.0, and the buffer B: 30% acetonitrile, 40 mM KH2PO4, 0.2% tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, pH 7.0, in gradient mode: 100% of the buffer B in 20 min, was used in this analysis.

Cellular Accumulation

Cellular accumulation of rhodamine-labeled Nanogel was examined in breast carcinoma cell lines as described earlier (19). Cells were treated with rhodamine-labeled nanogels (0.01 mg/ml) in the serum-free assay buffer for 2 h at 37 °C. After treatment, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS containing 1% BSA and then solubilized in 1% Triton X-100 solution. Fluorescence associated with the cells was measured at λex = 549 nm and λem = 577 nm, and obtained values were normalized by protein content (Pierce BCA protein assay) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity Analysis

Cytotoxicity of CTP-loaded nanogels was determined using the standard MTT assay (20). Briefly, serial dilutions of nanogel-CTP complexes in the assay buffer (122 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM KCl, 1.2 mM Mg(SO4)2, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 0.4 mM K2HPO4, 10 mM glucose and 10 mM HEPES ) were incubated with the cells for 24 h at 37 °C. Samples were washed with 100 μl of assay buffer and grown for three days in a full culture medium changed daily. Then, 25 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added and cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. The medium and indicator dye were washed out with PBS and cells were lysed with 20% sodium dodecylsulfate in 50% aqueous dimethylformamide (100 μl) overnight at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm and cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the initial absorbance values obtained for control non-treated cells. The IC50 values were calculated for 6–8 parallels using the Graph Pad Prizm software.

Tissue Biodistribution Study

In animal study described below, cage size and animal care conformed to the IACUC guidelines. Female Balb/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), 6–8 weeks of age, weight 20–23g, were assigned to one of five groups (five animals per cage per group). Animals of the first group received single doses of 2 μCi of 3H-CTP and 0.2 mg of cold CTP (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 100 μl of HBS intravenously via tail vein. Other groups received injections of 1 mg of nanogel formulations containing 2 μCi of 3H-CTP and 0.2 mg of cold CTP in 100 μl of HBS. Dispersion of nanogels in HBS was initially mixed with 3H-CTP, incubated for 30 min on ice, then mixed with cold CTP solution and again incubated for 30 min. This solution was spinned for 1 min at 12,000 g and directly used for injections. Samples of plasma and selected tissues were collected 90 min post-dose. The following tissues were collected: liver, lung, kidney, spleen and brain, weighed and homogenized in Tissue solubilizer (0.5–0.7 ml) prior to analysis. Homogenized tissue or plasma samples (100 μl) were placed in scintillation cocktail, and radioactive counts were measured. Drug accumulation in tissues (%ID/g) and tissue/blood ratio values were calculated as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Synthesis of Nanogels

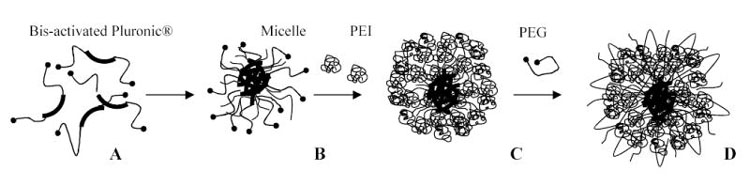

For preparation of nanogels we used two synthetic approaches. The first was described previously and consisted in the conjugation of polymers in heterogeneous phase of the dichloromethane-in-water emulsion (16). In order to simplify the whole synthetic procedure and reduce utilization of the environmentally hazardous organic solvent, we proposed a novel approach to preparation of nanogels. This second approach is based on the micelle-forming property of amphiphilic block copolymers, Pluronic® (Poloxamer) having a PEO-PPO-PEO structure. Many of these block copolymers are able to form polymeric micelles at concentrations as low as 0.01 mg/ml. The synthetic procedure consisted of three simple steps: (1) activation of both ends of Pluronic® molecules and dispersion in water at a concentration higher than the critical micellization concentration (CMC) of this type of Pluronic®, (2) interaction of the polymeric micelles with PEI and (3) cross-linking and modification of the Pluronic®-PEI micelles with activated PEG molecules as shown in Figure 2. The whole synthesis is a one-pot procedure performed by sequential addition of aqueous solutions of nanogel components. We have obtained three types of nanogels using the micellar approach, NGM(F127), NGM(P85) and NGM(P123) and their properties, together with properties of nanogels obtained by the emulsification/evaporation method, e.g. NG(PEG), NG(F68), NG(F127), NG(P85) and NG(P123), are all listed in Table I. The average obtained polymer to PEI weight ratio was about seven with initial Pluronic® to PEI ratio equal to two. The crude nanogels were purified by gel permeation chromatography using Sephacryl S-200 to remove very large particles, small molecular conjugates and initial polymer components. The obtained white solid lyophilized material was readily swollen and dispersed in water forming transparent particles with hydrodynamic diameters between 100 and 300 nm. Mass recovery was usually higher than 60–70%.

2.

Nanogel synthesis using the micellar approach. Activated Pluronic® block copolymers (A) formed micelles (B) in aqueous solutions, which could be covered with a layer of PEI (C) cross-linked by activated PEG molecules (D).

Complexes with Nucleoside 5′-Triphosphate

Nanogel solutions were directly mixed with solution of nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (CTP); fast formation of ionic complexes between PEI-backbone of nanogels and CTP occurred spontaneously, which was demonstrated by a significant 2–2.5-fold reduction of the observed hydrodynamic diameter of nanogels (Table 1). The size of unloaded nanogel usually showed no visible dependence on the nature of polymer used for the synthesis and was in the range of 100–300 nm. The size of nanogels obtained by micellar approach also fell in this range. By contrast, CTP-loaded nanogels displayed diameters mostly lower than 100 nm, and only the Pluronic® P85-based nanogel showed a larger diameter in the range of 120–140 nm. These complexes lyophilized after a short dialysis and could be then stored in dry form at 4ºC for many months without any signs of significant degradation of nucleoside 5′-triphosphate (data not shown).

Table 1.

Composition and particle size of nanogels

| Hydrodynamic diameter, nm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanogel | Total N, μmol/mg* | Weight ratio polymer/PEI* | unloaded** | CTP-loaded*** |

| NG(PEG) | 3.5 | 5.6 | 152±6 | 84±3 |

| NG(F127) | 2.3 | 9.1 | 113±0 | 70±2 |

| NG(F68) | 2.7 | 7.6 | 176±4 | 74±0.5 |

| NG(P85) | 2.6 | 7.9 | 297±4 | 120±1 |

| NGM(F127) | 3.0 | 6.6 | 132±4 | 69±1 |

| NGM(P85) | 2.2 | 9.5 | 270±3 | 144±4 |

| NGM(P123) | 2.7 | 7.6 | 102±1 | 69±0.5 |

Data obtained by elemental analysis. Weight ratio was calculated based on the total nitrogen (N) content for PEI: 23.2 μmol/mg (theor.).

Nanogels in PBS, at 1 mg/ml.

CTP-nanogel complex (N/P ratio 3) in PBS, at 0.1 mg/ml.

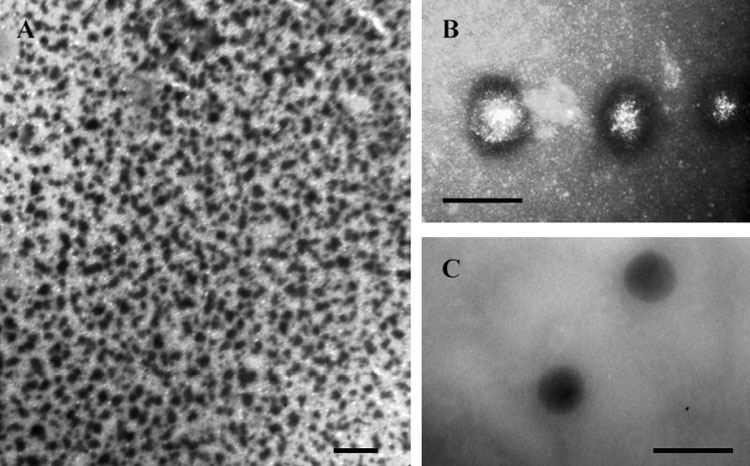

Transmission electron microscopy demonstrated the formation of spherical particles following the CTP binding with Cu2+-stained nanogels and compaction of CTP-PEI complexes into the structures with a dense core (Fig.3). The only difference observed for nanogels composed of the lipophilic Pluronic® P123 and synthesized using micellar approach was their distinct morphology characterized by a higher peripheral electron density. Evidently, hydrophilic PEG chains, which are not stained by Cu2+ cations, surround the compact core of CTP-PEI complexes, stabilize their aqueous dispersion, and shield them from interactions with macromolecules. However, lipophilic segments of Pluronic®-based nanogels evidently become more efficiently exposed following formation of a dense core in order to enhance the efficacy of nanogel interactions with cellular membranes.

3.

Transmission electron microscopy of CTP-loaded nanogels contrasted by Cu2+ cations: NG(F127) (A, bar - 500 nm), NGM(P123) (B, bar - 100 nm), and NG(F68) (C, bar - 100 nm).

Protection of the encapsulated CTP against enzymatic degradation was studied using ion-pair HPLC analysis of nucleotides. Complexes of CTP with nanogels immediately dissociated in the presence of ion-pairing tetra(n-butyl)ammonium cations following the injection of nanogel formulations in the column, where nucleoside and nucleotides could be separated as discrete peaks. Nanogel-formulated CTP showed an enhanced resistance to hydrolysis by the intestinal alkaline phosphatase. Free CTP was digested more than three times as much as encapsulated CTP in the enzyme assay (Table 2). The total balance of other nucleotides was also improved in the case of encapsulated CTP; this is an additional advantage because any type of phosphorylated NA can be active during the treatment of cancer cells.

Table 2.

Protection of CTP formulations with nanogels*

| Nanogel | Initial complex | Phosphatase-treated |

|---|---|---|

| NG(PEG) | 93.5 | 38.0±2.5 |

| NG(F127) | 93.0 | 26.6±1.9 |

| NG(F68) | 92.0 | 28.5±1.4 |

| NG(P85) | 88.7 | 34.5±0.7 |

| NGM(P123) | 91.7 | 29.0±1.1 |

| CTP w/o NG | 92.1 | 10.1±0.6 |

Based on ion-pair HPLC data. The CTP peak areas are presented as a percentile of total integrated HPLC areas (n=3, SEM).

Nucleoside 5′-triphosphates are small molecule that have three negative charges at physiological conditions. We studied in vitro drug release of CTP from the complex with nanogels in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, using an equilibrium dialysis approach at 25°C. Released CTP and products of its hydrolysis freely diffused from the incubated cell through the dialysis membrane in the equilibrating buffer, while nanogel-complexed drug remained inside. Change in the quantity of nanogel-loaded drug was measured by UV absorbance directly from the cell at different time points. We observed an initial phase of relatively fast drug release during the first 24 h, when about 50–70% of the drug was released from the nanogel. During the slow second phase, from 24 to 48 h, the drug release was five times slower than the initial phase. NMR spectra of nanogels demonstrated that the PEI-backbone of nanogels was composed of primary, secondary and tertiary amino groups with molar ratio 1:2:1 and only primary (pKa 9.2) and secondary (pKa 6.5) amines could be protonated at pH 7.4 (14). Evidently, binding of these amino groups with the phosphate groups of CTP is different, e.g. the binding of phosphate group with primary amino groups may be stronger than to the secondary amino groups, which means that 1/3rd of the encapsulated drug could be bound more strongly to the nanogel backbone than another 2/3rd of the drug. This might partly explain the partial stability of the encapsulated CTP to enzymatic hydrolysis (Table 2).

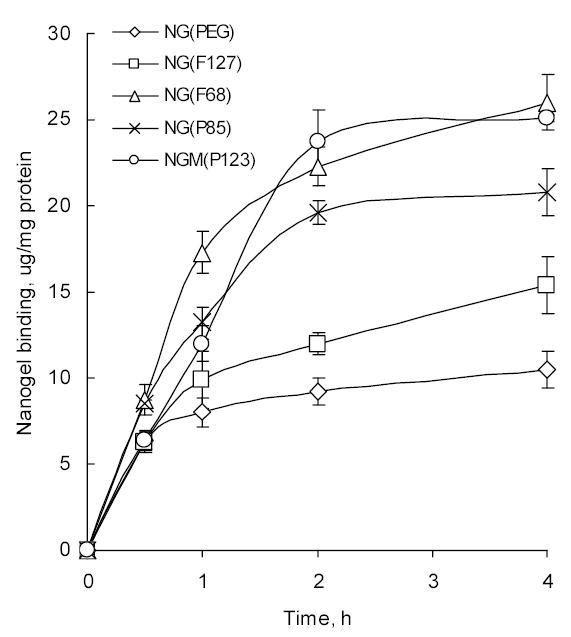

Affinity to Cellular Membranes

The lipophilic properties of Pluronic® block copolymers primarily depend on the length of poly(oxypropylene) block. In this paper, we explored how nanogels composed of different Pluronic® molecules and synthesized by two different procedures bind cellular membranes of cancer cells. To evaluate separately the degree of binding with cellular membrane and internalization of nanogels, we first studied the interaction of nanogels with isolated cellular membranes. For binding studies, cellular membranes were isolated from MCF-7 cells and incubated with 3H-labeled nanogels at 37°C for different time periods. Membrane-bound nanogel was precipitated by centrifugation and radioactivity associated with the membrane was counted. Binding of nanogels was expressed as μg/mg of membrane protein (Fig. 4). The binding curves showed saturation after about 2 h of incubation and binding efficiency of different nanogels increased in the following order: NG(PEG)<NG(F127)<NG(P85)<NG(F68)=NGM(P123). Mostly this trend reflects increasing length of the PPO block in corresponding Pluronic®-based nanogels. Initial phase of binding (0–0.5 h) was fast and mostly independent of the polymer composition of nanogels.

4.

Binding of nanogels to MCF-7 isolated cellular membranes. The same amount of cellular membranes (1 mg/ml protein) and 3H-labeled nanogels were used in each experiment. The data are the means ± SEM (n = 3).

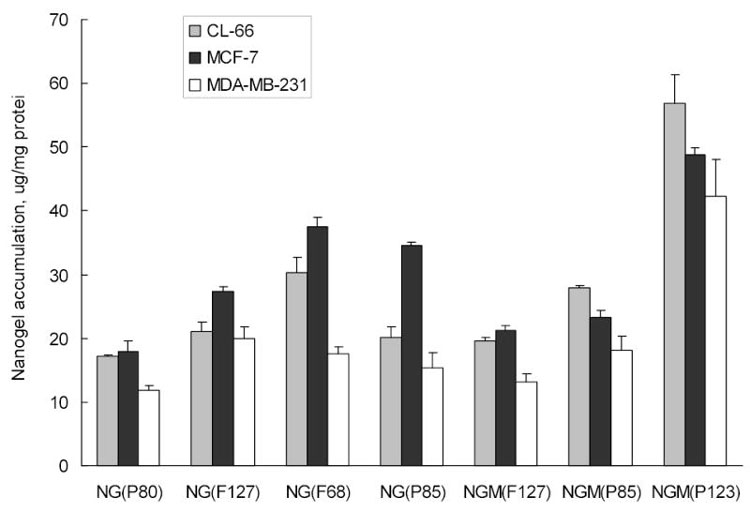

Cellular Accumulation

In this part we compared cellular accumulation of rhodamine-labeled nanogels in various types of breast carcinoma cells, mouse CL-66 and human MCF-7 and MDA-MB231 lines. Cells were treated with nontoxic concentrations of rhodamine-labeled nanogels (0.005–0.01 mg/ml) for 2 h, and then lysed. The cell-associated fluorescence was measured and normalized by the protein content in each sample. Nanogel association with cells was highest for NG(F68), NG(P85) and NGM(P123); intermediate for NG(F127) and NGM(P85), and lowest for NG(PEG) and NGM(F127) (Fig.4). MDA-MB-231 and CL-66 demonstrated lower levels of nanogel association compared to MCF-7 cells, but the observed general trend was the same. Cellular association of nanogels is an integral process that includes binding with cellular membrane, internalization and accumulation in the cytosol. The percentage of associated nanogels that internalized can be calculated by subtraction of the nanogel amount bound to the isolated cellular membranes at the same time points. This internalization was higher for nanogels composed of Pluronic® with lower HLB, e.g. 16–24μg/mg for NGM(P123), NG(P85) and NG(F68) and 10–15μg/mg for NG(PEG) and NG(F127), and constituted about 50% of the total quantity of cell-associated nanogels following 2 h-incubation. The difference between membrane-bound and internalized parts of nanogels was even higher at time point 4h. In general, these data provide evidence of an efficient drug release from the studied drug-nanogel formulations following binding of nanogels with cellular membranes and internalization into cancer cells.

Cytotoxicity

Application of nanogels for delivery of cytotoxic NTP makes nanogel cytotoxicity an additional factor in increasing the efficacy of drug-nanogel formulations. However, non-specific cytotoxicity of nanogels caused by accumulation in various tissues and organs remains an important question. In general, drug carriers with lower levels of intrinsic cytotoxicity are regarded as more advantageous. Therefore, in this study we compared cytotoxicity of various nanogels loaded with non-toxic CTP as a model drug in two human breast carcinoma cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 (Table III). Cytotoxicity of nanogels was significantly lower than cytotoxicity of PEI itself. Hydrophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels, such as NG(F127), NG(F68) and NGM(F127), were 2–3 times less cytotoxic compared to lipophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels. Also nanogels obtained by micellar approach demonstrated a comparable cytotoxicity with nanogels obtained by standard method. The metastatic MDA-MB-231 cell line was more sensitive to the nanogel treatment and observed IC50 values were about 6–20 times lower compared to MCF-7 cell line. These results suggest that application of drug-nanogel formulations may be especially effective in the treatment of advanced metastatic types of breast cancer.

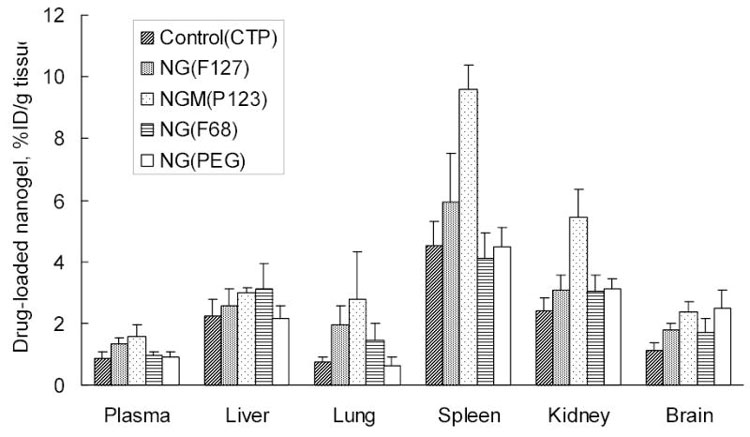

Mouse Tissue Biodistribution

Injected doses of drug-loaded nanogels (50 mg/kg) were well tolerated by animals. Obtained data on the biodistribution of drug (3H-CTP) alone, and drug formulations with nanogels NG(PEG), NG(F68), NG(F127) and NGM(P123) are shown in Fig. 6. Evidently, 3H-CTP is rapidly degraded in circulation to the 3H-cytidine and accumulation data for the free injected drug are related to this product. Pyrimidine nucleoside transporters are widely distributed in the body. The drug was quickly removed from circulation and mainly distributed in liver, spleen and kidney. We observed 50–90% increase in %ID/g in serum only for two nanogels, NG(F127) and NGM(P123). Drug retention in the first passing organ, liver, was slightly higher for more lipophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels. RES macrophages and Kupfer cells in liver effectively consume large particles, while relatively small loaded nanogels demonstrate low retention. High accumulation levels for nanogel NGM(P123) were observed in the spleen, kidney and brain. Spleen passes large volumes of blood and effectively removes hydrophilic particles from circulation. Transport to the spleen was found to be significantly increased for NGM(P123), the most lipophilic of studied nanogels. The similar trend was observed in the lung and kidney that are also known as efficient accumulators of cationic polymers. NG(PEG) demonstrated low levels of retention in all these organs. Brain accumulation was 50–120% higher for all nanogels compared to the free drug, with NG(PEG) and NGM(P123) as the most effective carriers.

6.

Tissue distribution of 3H-CTP in mice 90 min following injection of free drug and drug formulations with nanogels NG(PEG), NG(F68), NG(F127) and NGM(P123). Data were given as mean ± SEM for n=5.

DISCUSSION

Our data demonstrate that hydrophilic polymers of Pluronic®/Poloxamer type can be used for the preparation of PEI-based nanogels, which substantially enhances the cell binding affinity of these drug carriers. Many PEI-based delivery systems were able to induce efficient escape of the encapsulated polynucleotide drugs from endosomes into the cytosol. We showed previously the ability of nanogel to deliver NTP into the cells in an intact form (13). An anticipated mode of drug release from nanogel formulations encapsulating nucleoside analogs in 5′-triphosphate form includes interaction of nanogels with cellular membranes before or after endocytosis. The polymer properties can significantly influence binding properties of polymeric drug carriers. Optimization of the polymeric composition of nanogels to increase cellular membrane affinity and cytosolic delivery of NTP was the major focus of this study.

Clearly, the PEI part of nanogels should remain unchanged in order to maintain the NTP binding capacity and important buffering property of nanogel carriers. Recently, we studied and compared conjugates of short PEI molecules with different Pluronic® block copolymers for drug formulation and intracellular/transcellular delivery of antisense oligonucleotides (17). A significant dependence on Pluronic® type and HLB was observed in cellular association and transcellular transport of these conjugated carriers. Hydrophobic Pluronic® P123 was able to significantly enhance cellular association of oligonucleotides with cancer cells; while, Pluronic® P85 with an intermediate HLB was shown to be more efficient in transcellular transport. In the development of systemic drug delivery systems it is important for the carrier to have a minimal interaction with serum proteins. PEGylation of the surface of drug carriers has been shown to be the most successful way to minimize this interaction. In this paper we compared properties of nanogels composed of Pluronic® and PEG in physicochemical studies, in in vitro studies using breast carcinoma cell lines and in in vivo experiments. There should be an optimal HLB balance between lipophilic PPO blocks that are responsible for interaction with cellular membrane and hydrophilic PEO blocks that shield the polymer structure from serum proteins. We demonstrated in these experiments how the polymer structure of nanogels influences the membrane binding, internalization, drug release in vitro, and tissue biodistribution in vivo. Based on this data, some promising nanogel candidates for delivery of NTP among nanocarriers composed of large hydrophilic Pluronic®/Poloxamers were identified.

Successful candidates for delivery of anti-cancer cytotoxic drugs should comply with the following requirements: (1) low non-specific toxicity of the drug carrier at therapeutic doses, (2) efficient association and internalization into cancer cells, and (3) fast drug release from carrier to ensure efficient killing of cancer cells and prevention of drug resistance. Nanogels composed of PEG and PEI showed drastically lower cytotoxicity compared with the corresponding PEI. The polymer to PEI weight ratio was mainly responsible for cytotoxicity of nanogels (14). At the ratio higher than 5, nanogels exhibit the lowest cytotoxicity. We prepared a set of novel nanogels with the polymer to PEI ratio higher than 5. These two studied nanogels, NG(F127) and NG(F68), demonstrated the lowest cytotoxicity in breast carcinoma cells. (Note: Pluronic® F127 also carries the name of Poloxamer 407 and Pluronic® F68 - Poloxamer 188, approved by FDA for in vivo applications). Nanogels composed of more lipophilic nanogels like NG(P85) and NGM(P123) were more cytotoxic. All studied nanogels demonstrated practically identical in vitro drug release profiles and protection of encapsulated NTP against enzymatic degradation. Nevertheless, these nanogels demonstrated completely different membranotropic properties. Even the most hydrophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels bound isolated cellular membranes more efficiently then PEG-based nanogels. We also observed a similar trend in experiments with proliferating breast carcinoma cells. It was found that nanogels NG(F68), NG(F127), NG(P85), and NGM(P123) associated with cancer cells much better than NG(PEG). Based on the properties of these nanogels, we believe that NG(F68) and NGM(P123) can be considered the best candidates for drug delivery of NTP analogs. NG(F127) and NG(P85) could be considered as secondary carrier candidates.

Our data on the intracellular release of encapsulated drug also suggest that these candidate nanogel carriers are capable of the efficient NTP drug release in the cytosol. This is a very important property because these carriers are evidently capable of releasing part of the encapsulated drug following their interactions with cellular membranes. Triggered drug release is a feature of advanced drug delivery systems and usually occurs in response to temperature change, ultrasound, irradiation or enzymatic activity (21–24). We earlier postulated the existence of enhanced drug release from nanogels due to the interaction with cellular membranes, and recently this point of view received experimental confirmation (13). The actual drug release mechanism will ultimately depend on the interaction of nanogels’ PEI-backbone with membrane phospholipids. Therefore, membranotropic properties of neutral polymers in the nanogel structure will provide additional benefits in the form of fast drug release in the cytosol. This ability to release the encapsulated drug following the interaction of a drug carrier with targeted cells remains the most important factor in choosing an optimal drug carrier. Our studies will help define optimal drug carrier formulations.

Comparison of drug tissue biodistribution following an i.v. injection of some selected drug-loaded nanogels demonstrated a higher affinity of Pluronic®-based nanogels to many organs compared to the drug alone or PEG-based nanogel. However, except of NGM(P123), there was no significant asymmetry in biodistribution of these carriers. Based on these results, two nanogels, NG(F127) and NG(F68) can be selected as the most promising candidates for development of novel vectorized nanocarriers for systemic administration of anticancer/antiviral nucleoside analogs. Post-synthetic modification of nanogels with peptide ligands connected through a PEG linker will provide a specific targeting and additional surface shielding, making better their circulation and biodistribution properties.

An important feature of Pluronic® as a polymer for synthesis of nanogels is its strong mucoadhesive property (25–28). Mucoadhesive polymers have a number of advantages compared to other biocompatible polymers. Mucoadhesion increases the contact between drug-loaded nanogels and the mucous surface of many cell types and can significantly enhance the cell permeability of drug. Application of drug delivery systems composed of mucoadhesive polymers resulted in prolonged residence time and protection of the encapsulated active compounds from enzymatic degradation. This is especially important for drug delivery to epithelial cells in respiratory and digestive tracts. We believe that this property of nanogels can be useful for the development of more efficient formulations against cancers related to these organs.

Rational design of systemic drug delivery systems, where the polymer architecture is only the first step, may include also surface modifications and proper vectorization of these carriers with targeting ligands. The present study may be particularly useful in the determination of nanogel candidates for subsequent vectorization of these carriers with cancer-specific peptide ligands and application to in vivo studies. Investigation of the vectorized nanogels and their biodistribution in cancer models will follow.

CONCLUSIONS

A novel approach for nanogel synthesis is proposed based on the micelle-forming properties of Pluronic® molecules. The size of unloaded nanogels was in the range of 100–300 nm, showing no strong dependency on the nature of polymer and approach used for the synthesis. Nucleotide drug-loaded nanogels displayed diameters around 100 nm; only the Pluronic® P85-based nanogel showed diameter in the range of 120–140 nm. Nanogel-formulated CTP showed an enhanced resistance to hydrolysis by the intestinal alkaline phosphatase. In vitro drug release from nanogel formulations was also similar among various nanogels. The membrane-binding properties of different nanogels increased in the following order: NG(PEG)<NG(F127)<NG(P85)<NG(F68) = NGM(P123). Nanogel association with breast carcinoma cell lines was also highest with NG(F68), NG(P85) and NGM(P123); NG(F127) and NGM(P85) showed intermediate association levels, and NG(PEG) and NGM(F127) displayed the least efficient binding. Hydrophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels, such as NG(F127), NG(F68) and NGM(F127), were several times less cytotoxic compared to lipophilic Pluronic®-based nanogels. Therefore, nanogels composed of hydrophilic Poloxamers (Pluronic® F68 and F127) and displaying advanced properties compared to NG(PEG) may be considered as prospective candidates for encapsulation of therapeutic nucleoside analogs. Drug delivery systems based on Poloxamer-nanogels for formulation of active NTP form of nucleoside analogs can be developed into novel therapeutic antiviral or anti-cancer drugs and approaches to targeted chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

5.

Cellular uptake of rhodamine-labeled nanogels in different breast carcinoma cell lines following 2h-incubation with CTP-loaded nanogel formulations (0.01 mg/ml). The data are means of three measurements.

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of the CTP-loaded nanogels in human breast carcinoma cells*

| Nanogel | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 |

|---|---|---|

| NG(PEG) | 0.26 | 0.04 |

| NG(F127) | 0.06 | 0.003 |

| NG(F68) | 0.08 | 0.005 |

| NG(P85) | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| NGM(P123) | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| NGM(P85) | 0.025 | 0.003 |

| NGM(F127) | 0.08 | 0.009 |

| PEI(25kDa) | 0.002 | 0.0001 |

IC50 values, mg/ml, at 24h-treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by NIH R01 grant CA102791 (S.V.V.). Authors are extremely grateful to Drs. Elena Batrakova and William Chaney for helpful discussion and Michael Jacobsen for valuable assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Duncan R. The dawning era of polymer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galmarini CM, Mackey JR, Dumontet C. Nucleoside analogues and nucleobases in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:415–24. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzarini J. Metabolism and mechanism of antiretroviral action of purine and pyrimidine derivatives. Pharm World Sci. 1994;16:113–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01880662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonelli G, Turriziani O, Verri A, Narciso P, Ferri F, D’Offizi G, Dianzani F. Long-term exposure to zidovudine affects in vitro and in vivo the efficiency of phosphorylation of thymidine kinase. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:223–8. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoever G, Groeschel B, Chandra P, Doerr HW, Cinatl J. The mechanism of 3′-azido-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine resistance to human lymphoid cells. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:743–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner CR, Iyer VV, McIntee EJ. Pronucleotides: toward the in vivo delivery of antiviral and anticancer nucleotides. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:417–51. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200011)20:6<417::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIntee EJ, Remmel RP, Schinazi RF, Abraham TW, Wagner CR. Probing the mechanism of action and decomposition of amino acid phosphomonoester amidates of antiviral nucleoside prodrugs. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3323–31. doi: 10.1021/jm960694f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Wijk GM, Hostetler KY, Kroneman E, Richman DD, Sridhar CN, Kumar R, van den Bosch H. Synthesis and antiviral activity of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine triphosphate distearoylglycerol: a novel phospholipid conjugate of the anti-HIV agent AZT. Chem Phys Lipids. 1994;70:213–22. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(94)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattel L, Ceruti M, Dosio F. From conventional to stealth liposomes: a new frontier in cancer chemotherapy. Tumori. 2003;89:237–49. doi: 10.1177/030089160308900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Immordino ML, Brusa P, Rocco F, Arpicco S, Ceruti M, Cattel L. Preparation, characterization, cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of liposomes containing lipophilic gemcitabine prodrugs. J Control Release. 2004;100:331–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosasso P, Brusa P, Dosio F, Arpicco S, Pacchioni D, Schuber F, Cattel L. Antitumoral activity of liposomes and immunoliposomes containing 5-fluorouridine prodrugs. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:832–9. doi: 10.1021/js9604467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pateland KR, Baldeschwieler JD. Treatment of intravenously implanted Lewis lung carcinoma with liposome-encapsulated cytosine arabinoside and non-specific immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 1984;34:415–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinogradov SV, Kohli E, Zeman AD. Cross-Linked Polymeric Nanogel Formulations of 5′-Triphosphates of Nucleoside Analogues: Role of the Cellular Membrane in Drug Release. Mol Pharm. 2005;2:449–461. doi: 10.1021/mp0500364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinogradov SV, Zeman AD, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Polyplex Nanogel formulations for drug delivery of cytotoxic nucleoside analogs. J Control Release. 2005;107:143–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant S. Ara-C: cellular and molecular pharmacology. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;72:197–233. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60703-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Nanosized cationic hydrogels for drug delivery: preparation, properties and interactions with cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:135–47. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinogradov SV, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV. Nanogels for oligonucleotide delivery to the brain. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:50–60. doi: 10.1021/bc034164r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamada H, Tsuruo T. Characterization of the ATPase activity of the Mr 170,000 to 180,000 membrane glycoprotein (P-glycoprotein) associated with multidrug resistance in K562/ADM cells. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4926–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinogradov S, Batrakova E, Li S, Kabanov A. Polyion complex micelles with protein-modified corona for receptor-mediated delivery of oligonucleotides into cells. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:851–60. doi: 10.1021/bc990037c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Y. S. Kaneko, K.; Okano, T. . Temperature-responsive hydrogels as intelligent materials, Biorelated Polymers and Gels, Academic Press, 1998, pp. 29–66.

- 22.Kashyap N, Kumar N, Kumar MN. Hydrogels for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2005;22:107–49. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v22.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peppas NA, Wood KM, Blanchette JO. Hydrogels for oral delivery of therapeutic proteins. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:881–7. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.6.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kabanov AV, Lemieux P, Vinogradov S, Alakhov V. Pluronic block copolymers: novel functional molecules for gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:223–33. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alakhov V, Pietrzynski G, Patel K, Kabanov A, Bromberg L, Hatton TA. Pluronic block copolymers and Pluronic poly(acrylic acid) microgels in oral delivery of megestrol acetate. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56:1233–41. doi: 10.1211/0022357044427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bromberg L, Temchenko M, Alakhov V, Hatton TA. Bioadhesive properties and rheology of polyether-modified poly(acrylic acid) hydrogels. Int J Pharm. 2004;282:45–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleary J, Bromberg L, Magner E. Adhesion of polyether-modified poly(acrylic acid) to mucin. Langmuir. 2004;20:9755–62. doi: 10.1021/la048993s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tirnaksizand F, Robinson JR. Rheological, mucoadhesive and release properties of pluronic F-127 gel and pluronic F-127/polycarbophil mixed gel systems. Pharmazie. 2005;60:518–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.