Abstract

The first complete-genome DNA microarray was constructed for a hyperthermophile or a nonhalophilic archaeon by using the 2,065 open reading frames (ORFs) that have been annotated in the genome of Pyrococcus furiosus (optimal growth temperature, 100°C). This was used to determine relative transcript levels in cells grown at 95°C with either peptides or a carbohydrate (maltose) used as the primary carbon source. Approximately 20% (398 of 2065) of the ORFs did not appear to be significantly expressed under either growth condition. Of the remaining 1,667 ORFs, the expression of 125 of them (8%) differed by more than fivefold between the two cultures, and 82 of the 125 (65%) appear to be part of operons, indicating extensive coordinate regulation. Of the 27 operons that are regulated, 5 of them encode (conserved) hypothetical proteins. A total of 18 operons are up-regulated (greater than fivefold) in maltose-grown cells, including those responsible for maltose transport and for the biosynthesis of 12 amino acids, of ornithine, and of citric acid cycle intermediate products. A total of nine operons are up-regulated (greater than fivefold) in peptide-grown cells, including those encoding enzymes involved in the production of acyl and aryl acids and 2-ketoacids, which are used for energy conservation. Analyses of the spent growth media confirmed the production of branched-chain and aromatic acids during growth on peptides. In addition, six nonlinked enzymes in the pathways of sugar metabolism were regulated more than fivefold—three in maltose-grown cells that are unique to the unusual glycolytic pathway and three in peptide-grown cells that are unique to gluconeogenesis. The catalytic activities of 16 metabolic enzymes whose expression appeared to be highly regulated in the two cell types correlated very well with the microarray data. The degree of coordinate regulation revealed by the microarray data was unanticipated and shows that P. furiosus can readily adapt to a change in its primary carbon source.

Hyperthermophiles are microorganisms that grow optimally at temperatures of 80°C and above (53). Most are classified as archaea, and many utilize peptides as a carbon source and reduce elemental sulfur (S0) to H2S (53). Some, including several species of Pyrococcus and Thermococcus, are able to metabolize poly- and oligosaccharides as well as peptides (5, 6, 16). Herein, we focus on the primary carbon metabolism of one of the best studied of all hyperthermophiles, Pyrococcus furiosus. This organism was isolated from a shallow marine volcanic vent and grows optimally near 100°C with either peptides or carbohydrates used as its carbon and energy sources (16).

Prior studies of the primary pathways for carbon metabolism by P. furiosus have yielded several surprises. In particular, it contains a modified Embden-Meyerhof pathway with two ADP- rather than ATP-dependent kinases, glucokinase and phosphofructokinase (26, 55). In addition, the expected glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) are replaced by a single enzyme, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (GAPOR) that catalyzes the direct oxidation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate to 3-phosphoglycerate by using ferredoxin as an electron acceptor (36). The pyruvate produced by glycolysis is oxidized to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) by another ferredoxin-linked enzyme, pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (POR), and ATP is formed by substrate-level phosphorylation by another novel enzyme, acetyl-CoA synthetase I (ACS I) (33). Reduced ferredoxin is oxidized either by a respiratory-type membrane-bound hydrogenase complex that both translocates and reduces protons, or by an as-yet-uncharacterized S0-reducing system (45; R. Sapra, K. Bagramyan, and M. W. W. Adams, submitted for publication). The biosynthesis of amino acids from glycolytic intermediates is assumed to occur by the conventional pathways found in mesophilic bacteria, but this has not been investigated to any extent.

On the other hand, during growth of P. furiosus on peptides, carbon is channeled to sugars by what appears to be a slightly modified version of the classical gluconeogenic pathway. This does contain the expected GAPDH and PGK, even though they do not function in glycolysis (46, 58), but the enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate is not defined, and two candidates have been proposed (40, 59). Energy is conserved during amino acid catabolism via the acyl- and aryl-CoAs that are generated by transamination and oxidation of the 2-ketoacids by a family of ferredoxin-dependent, 2-ketoacid oxidoreductases. These utilize 2-ketoglutarate (KGOR), aromatic (IOR), or branched-chain 2-ketoacids (VOR). The CoA derivatives are converted to organic acids by ACS I and its isoenzyme, ACS II, with concomitant generation of ATP (33).

How the pathways of sugar and amino acid metabolism are regulated in P. furiosus and related organisms is largely unknown. Studies of the expression of some individual genes have indicated that glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and GAPOR are the key regulation points in glycolysis (58, 60), while fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (FBA) serves the same role in the gluconeogenic pathway (51). In a preliminary study, P. furiosus grown either on maltose or peptides with and without S0 provided the first evidence for a significant regulatory role for both S0 and the carbon source, based on the activities of several key metabolic enzymes (1). Herein, we have extended this analysis by using the same cells to determine whole-genome transcriptional profiles by using DNA microarrays.

The application of whole-genome DNA microarrays (47) has revolutionized functional genomics in eukaryotic systems, e.g., reference 43, but there have been far fewer analyses conducted by using prokaryotes. In the last 2 years, studies on 14 species have been reported, including Bacillus subtilus (65), Escherichia coli (38), a cyanobacterium (20), and an extreme halophile (4). However, complete genome analyses have yet to be applied to either a nonhalophilic member of the archaeal domain or to a thermophilic or hyperthermophilic organism. Indeed, for such organisms, results from only one partial genome array (271 open reading frames [ORFs]) have been reported, and this study focused on the effects of S0 on the metabolism of P. furiosus (49). Herein, we describe transcriptional analysis that was performed by using all of the 2,065 ORFs that have been annotated in the complete genome of P. furiosus (42). The results reveal extensive coordinate regulation in response to a change in the primary carbon source—a conclusion validated to a large extent by enzymatic and metabolic product analyses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Array design and RNA preparation.

Primers were designed for the 2,065 ORFs in the P. furiosus genome (http://comb5-156.umbi.umd.edu/genemate/) by using Array Designer (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, Calif.) and custom scripts (F. Poole., personal communication). Specific 50-mer oligonucleotides were designed for ORFs PF1327, PF1852, and PF1910 in addition to the full-length probes, as these ORFs have highly similar sequences. All primers were purchased from MWG Biotech (High Point, N.C.). PCR products were generated for 1,949 complete ORFs, and for the remaining 107 ORFs, primers were designed to give products of about 1 kb in length (unless the target ORF was smaller). Products were obtained for all ORFs. These were purified with a 96 PCR purification kit (Telechem, Sunnyvale, Calif.), eluted in 50% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide, and spotted in duplicate on aminosilane-coated slides (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, Mass. and Asper, Tartu, Estonia) in 16 subarrays by using a robotic slide printer (Omnigrid; Genemachines, San Carlos, Calif.). The slides were processed as previously described (10).

P. furiosus (DSM 3638) was grown in batch mode in a 20-liter custom fermentor at 95°C in the presence of S0 with either peptides (hydrolyzed casein) or maltose used as the primary carbon source (1). The cells that were used to prepare RNA for the microarray analyses were identical to those from experiments that have been described previously (1). In that case, activity assays were performed for more than 20 enzymes involved in the primary metabolic pathways by using cytoplasmic and membrane fractions, and these results are referred to below. Samples (2,000 ml) of the same cultures were removed toward the end of log-phase growth (2 × 108 cells/ml), cooled on ice, and total RNA was extracted by using acid phenol extraction (61).

Preparation of cDNA and hybridization conditions.

Each cDNA was prepared as described previously (49), except that they were labeled differentially with Alexa dyes 488, 546, 594, or 647 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled cDNA pools derived from P. furiosus cells grown in the presence of peptides or maltose were combined and hybridized to the microarrays by using a Genetac hybridization station (Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, Mich.) for between 10 and 15 h. The slides were then washed automatically for 20 s in each of 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% Tween 20, 0.2× SSC-0.1% Tween 20, 0.2× SSC, and finally rinsed in distilled water and blown dry with compressed air. Fluorescence intensities of each of the four dyes were measured with a Scan Array 5000 slide reader (Perkin-Elmer) with the appropriate laser and filter settings. To obviate dye effects, each of the samples was labeled with different dyes between replicates and duplicates. However, we did not observe significant differences between the four dyes related to incorporation, fluorescent yield, or stability.

Data analysis.

Fluorescent spots on the microarrays were identified and quantitated by using the Gleams software package (Nutec, Houston, Tex.). The relative amounts of the transcripts were presented in a linear fashion by converting all ratios (maltose/peptides) to a log2 function. The detection limit of fluorescent signals was set arbitrarily to 1,000 intensity units, and such spots are not visible on the false overlay. Only ORFs that display intensities of more than twice the detection limit (2,000 arbitrary units) were considered valid. Each log2 value represents an average of four hybridization experiments performed in duplicate by using cDNA derived from four different cultures of P. furiosus: two grown on peptides and two grown on maltose. Standard deviations for these data are included. The results for each ORF therefore consisted of 16 pairwise comparisons between peptide and maltose cultures. Individual t-test procedures were conducted to identify the significantly differentially expressed ORFs and Holm's step-down P value adjustment procedure was performed (21) to give modified P values.

Enzyme assays.

Cell extracts used for all assays were prepared as described previously (1). Isocitrate dehydrogenase activity was measured at 85°C by the formation of NADPH by the previously described method (52), except that 50 mM N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[3-propanesulfonic acid] (EPPS) pH (7.5), was used as the buffer. Amylase activity was measured by the release of Remazolbrilliant Blue (41). A 0.6% (wt/vol) suspension of starch azure (Sigma, St Louis, Mo.) was washed in 50 mM EPPS (pH 7.5) containing 40 mM NaCl at 95°C for 2 min. The insoluble substrate was recovered by centrifugation and resuspended at 0.6% (wt/vol) in the same buffer. Cell extracts were incubated with the substrate suspension at 85°C with continuous mixing. Product release was measured at 595 nm (41). Acetolactate synthase was measured by incubating cell extracts in EPPS buffer (pH 7.5) in the presence of 50 mM pyruvate, 1 mM thiamine PPi, and 10 μM flavin adenine dinucleotide at 85°C. Formation of acetolactate was performed as described previously (64). GAPDH activity was measured by monitoring NADPH production as described previously (50). Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase (CPS) and carbamate kinase (CK) activities were estimated by measuring carbamoyl phosphate indirectly by using the ornithine transcarbamoylase pathway in cell extracts to produce citrulline (30). The reaction mixture used to measure both enzyme activities contained 50 mM EPPS (pH 8.0), 8 mM l-ornithine, 20 mM ATP, 0.4 mg of urease per ml (Sigma), and 100 mM sodium bicarbonate. The N sources for the CK and CPS assays were 200 mM ammonium chloride and 2.5 mM glutamine, respectively. The reaction (500 μl) was incubated at 60°C for 30 min and was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of concentrated sulfuric acid. Citrulline was determined as described previously (7). The methods for other enzyme assays are described in reference 1.

Determination of organic acids.

Samples of media (1 ml) were removed from growing cultures of P. furiosus at various points in the growth phase, and cells were collected by centrifugation. The supernatant fractions were acidified and extracted three times with an equal volume of ether. Organic acids were converted to their potassium salts by adding 1 M KOH to pH 8 and dried by lyophilization. To obtain derivatives of the organic acids, the dried samples were suspended in 2 ml of acetonitrile containing α,p-dibromoacetophenone with 18-crown-6 ether used as a catalyst to yield UV-absorbing compounds as described previously (14). The adducts of the common organic acids were separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography (Alliance 2690; Waters, Milford, Mass.) by using a C-18 column (150 by 3.9 mm) with a linear gradient of 45 to 75% (vol/vol) methanol in water. The adducts were detected with a photodiode array detector (Waters) at 260 nm. The identity of the organic acids was determined from standards and verified with electro spray mass spectrometry at the mass spectrometry facility of the University of Georgia.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Experimental protocols and data analysis.

A total of 2,065 ORFs are annotated in the genome sequence of P. furiosus (http://comb5-156.umbi.umd.edu/genemate/). Approximately 50% of these are designated (conserved) hypothetical and show no similarity to characterized ORFs in other genomes (42). Each of the 2,065 ORFs was cloned by PCR amplification and was arrayed onto glass slides. The arrays were used to assess differential gene expression in P. furiosus cells grown in the presence of S0 by using either peptides (hydrolyzed casein) or the disaccharide maltose as the primary carbon source. Results were obtained from RNA samples that were prepared from four different P. furiosus cultures, two grown independently on each carbon source. All possible hybridization combinations were performed twice in duplicate by using the four sources of RNA, giving rise to 16 data points for each of the 2,065 ORFs.

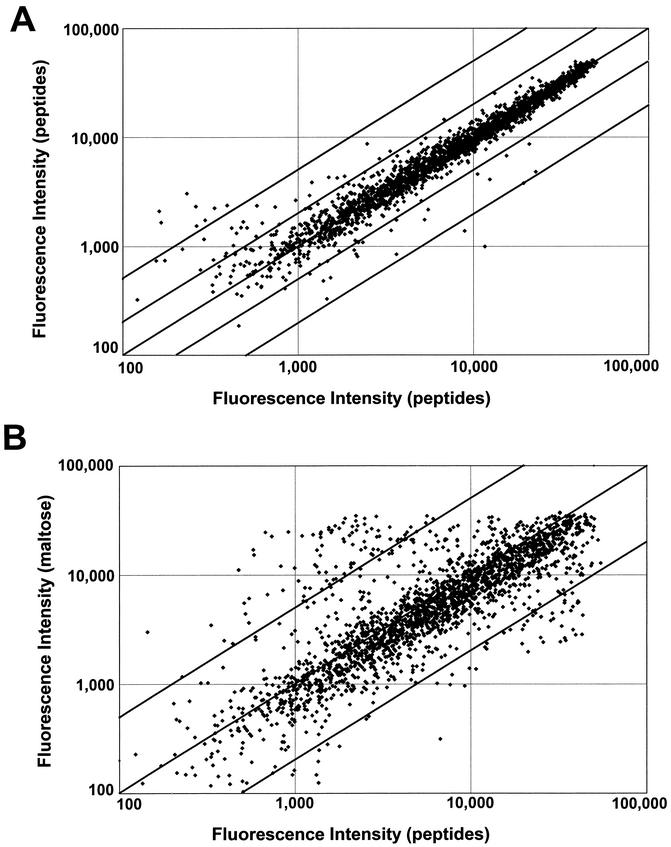

The efficacy of the microarray experiment is shown by using RNA samples derived from two different cultures of P. furiosus cells grown independently under the same set of conditions. These were differentially labeled and hybridized to the same slide. Figure 1A shows the two sets of signal intensities using cells grown on peptides. Intensities vary over a >103 range, and ORFs with intensities less than 2,000 arbitrary units (or twice the detection limit [Fig. 1A]) are considered not to be significantly expressed. As expected, low-intensity signals show a high standard deviation because of background fluorescence, but otherwise the data points from the majority of the ORFs lie close to the diagonal. As indicated by the multiple lines, more than a fivefold difference in signal intensity (outer lines in Fig. 1A) is readily discerned, while most ORFs display less than twofold change.

FIG. 1.

Fluorescence intensities of DNA microarrays. (A) cDNA vs cDNA derived from two independent cultures of cells grown with peptides as the carbon source. (B) cDNA versus cDNA derived from two independent cultures of cells grown with peptides or maltose as the carbon source. In panel A, the upper and lower diagonal line pairs indicate twofold and fivefold changes in the signal intensities, respectively, while only the lines indicating fivefold changes are given in panel B. See text for details.

As shown in Fig. 1B, a change in the primary carbon source from peptides to maltose has a clear effect on gene expression when viewed on a genome-wide basis (cf. Fig. 1A). Of the 2,065 ORFs analyzed, 311 had P values that were <0.05 (supplementary data [http://adams.bomb.uga.edu/pubs/sup238.pdf]). In the following, we focus on ORFs whose expression appears to be strongly regulated by the presence of peptides or maltose such that the signal intensity changes by at least fivefold (shown by the upper and lower diagonal lines in Fig. 1B. Approximately 80% (1,666 of 2,065) of the ORFs are significantly expressed under one or both growth conditions (intensity more than twofold greater than the detection limit). The expression of 125 (7.5%) ORFs are up-regulated by more than fivefold in either maltose- (total, 80) or peptide (total, 45)-grown cells, and these are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Statistical support for the 125 highly regulated ORFs is provided by a t test-based analysis (described in Materials and Methods). This analysis yielded P values of >0.05 for two ORFs (PF1686 and PF1701), 119 ORFs yielded P values of <0.01, and the remaining four ORFs yielded P values between 0.01 and 0.05 (Table 1 and 2). The remaining ORFs can be subdivided into those that appear to be up-regulated between two- and fivefold by maltose (total, 46) or peptides (total, 99) and those that are not significantly regulated (total, 1,396) under either condition, in addition to those that are not expressed (total, 399). Information on the ORFs not listed in Tables 1 and 2 are available as supplementary information (http://adams.bmb.uga.edu/pubs/sup238.pdf).

TABLE 1.

ORFs whose expression is dramatically up-regulated in maltose-grown cells and their potential operon arrangement

| Function and ORF | Descriptiona | Mean intensity ratio (log ± SD)b | Change in expression (fold)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| PF0101 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 4.4 ± 2.5 | 21.1 |

| TCA cycle | |||

| PF0201 | [Aconitase] | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 |

| PF0202 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase (52) | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 |

| PF0203 | Citrate synthase (35) | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 17.1 |

| [Glutamate biosynthesis] | |||

| PF0204 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 19.7 |

| PF0205 | [Glutamate synthase, alpha] | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 13.9 |

| PF0206 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 9.2 |

| [Arginine biosynthesis] | |||

| PF0207 | [Argininosuccinate synthase] | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 7.0 |

| PF0208 | [Argininosuccinate lyase] | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 5.3d |

| PF0209 | [Ribosomal protein s6 modification protein] | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 3.0d |

| PF0272 | Alpha-amylase (27, 28) | 4.7 ± 1.7 | 26.0 |

| PF0371 | [Putative transporter] | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 8.6 |

| PF0428 | [Partial alanyl-tRNA synthetase] | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 6.5 |

| PF0429 | [Putative proline permease] | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 7.5 |

| PF0450 | [Glutamine synthetase I] | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 19.7 |

| PF0464 | Glyceraldehyde-3-P Fd oxidoreductase (36) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 5.8 |

| PF0514 | [Alanine glycine permease] | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 5.3 |

| PF0651 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 |

| [Unknown] | |||

| PF0881 | [ABC transporter] | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 8.6 |

| PF0882 | [Hypothetical protein] | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 12.1 |

| PF0883 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 4.6 |

| PF0884 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 12.1 |

| [Branched amino acid biosynthesis] | |||

| PF0935 | [Acetolactate synthase] | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 17.1 |

| PF0936 | [Ketol-acid reductoisomerase] | 5.0 ± 2.5 | 32.0 |

| PF0937 | [2-Isopropylmalate synthase] | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 6.5 |

| PF0938 | [3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase, large] | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 6.1 |

| PF0939 | [3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase, small] | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 4.9 |

| PF0940 | [3-Isopropylmalate dehydrogenase] | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 6.1 |

| PF0941 | [Alpha-isopropylmalate synthase] | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 4.9 |

| PF0942 | [Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase] | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 5.7 |

| PF0962 | [Hypothetical protein] | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 5.3 |

| PF1025 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 5.7 |

| [Serine/threonine biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1052 | [Probable aspartokinase] | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 26.0 |

| PF1053 | [Aspartokinase II, alpha] | 5.6 ± 2.0 | 48.5 |

| PF1054 | [Homoserine kinase] | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 32.0 |

| PF1055 | [Threonine synthase] | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 27.9 |

| PF1056 | [Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase] | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 16.0 |

| PF1104 | [Homoserine dehydrogenase] | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 8.0 |

| [Unknown] | |||

| PF1109 | [Hypothetical protein] | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 10.6 |

| PF1110 | [Hypothetical protein] | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 4.6 |

| [Unknown] | |||

| PF1129 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 4.5 |

| PF1130 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 5.5 |

| [Methionine biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1266 | [Cystathionine gamma-lyase] | 4.6 ± 1.4 | 24.3 |

| PF1267 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 21.1 |

| PF1268 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 5.5 ± 16 | 45.3 |

| PF1269 | [Methionine synthase] | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 21.1 |

| Ferredoxin:NADPH oxidoreductase I | |||

| PF1327 | Fd NADPH oxidoreductase, alpha (32) | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 5.7 |

| PF1328 | Fd NADPH oxidoreductase, beta (32) | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 5.7 |

| [Unknown] | |||

| PF1536 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 4.3 |

| PF1537 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 3.7 |

| PF1538 | [N-ethylammeline chlorohydrolase] | 3.2 ± 06 | 9.2 |

| PF1592 | [Tryptophan synthase, beta] | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 12.1 |

| [Histidine biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1657 | [Histidyl-tRNA synthetase] | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 10.6 |

| PF1658 | [ATP phosphoribosyltransferase] | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 11.3 |

| PF1659 | [Histidinol dehydrogenase] | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 7.0 |

| PF1661 | [Glutamine amidotransferase] | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 4.0 |

| PF1662 | [HisA] | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 5.3 |

| PF1663 | [Imidazoleglycerol-phosphate synthase] | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 7.0 |

| PF1665 | [histidinol-phosphate aminotransferase] | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 4.0d |

| PF1670 | [Alkaline serine protease] | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 8.0 |

| [Branched amino acid biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1678 | [2-Isopropylmalate synthase] | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 42.2 |

| PF1679 | [3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase, large] | 5.0 ± 1.4 | 32.0 |

| PF1680 | [3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase, small] | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 16.0 |

| [Ornithine biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1682 | [Ribosomal protein s6 modification protein] | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 11.3 |

| PF1683 | [N-acetyl-γ-glutamyl-phosphate reductase] | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 13.9 |

| PF1684 | [Acetylglutamate kinase] | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 8.6 |

| PF1685 | [Acetylornithine aminotransferase] | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 |

| PF1686 | [Acetylornithine deacetylase] | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 7.5e |

| [Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1687 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 4.3 |

| PF1688 | [Transketolase N-terminal section] | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 9.8 |

| PF1689 | [Transketolase C-terminal section] | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 4.3 |

| PF1690 | [2-Dehydro-3-deoxyphosphoheptonate aldolase] | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 8.6 |

| PF1692 | [3-Dehydroquinate dehydratase] | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 6.5 |

| PF1693 | [Shikimate 5-dehydrogenase] | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 17.1 |

| PF1694 | [Archaeal shikimate kinase] | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 6.5 |

| [Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis] | |||

| PF1699 | [3-Phosphoshikimate 1-carboxyvinyltransferase] | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 4.9 |

| PF1700 | [Chorismate synthase] | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 4.0 |

| PF1701 | [Chorismate mutase] | 2.9 ± 2.1 | 7.5e |

| PF1702 | [Aspartate aminotransferase] | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 17.1 |

| PF1703 | [Prephenate dehydrogenase] | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 14.9 |

| PF1706 | [Tryptophan synthase, subunit beta] | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 4.3 |

| PF1708 | [Anthranilate synthase component II] | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 4.3 |

| PF1709 | [Anthranilate synthase component I] | 2.7 ± 1.4 | 6.5d |

| PF1710 | [Anthranilate phosphoribosyltransferase] | 2.9 ± 1.0 | 7.5 |

| PF1711 | [Indoleglycerol phosphate synthase] | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 17.1 |

| PF1713 | [Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, small] | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 8.0 |

| PF1739 | [Trehalose-maltose binding protein] | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 6.1 |

| [Maltose transport] | |||

| PF1740 | [Trehalose-maltose transport protein] | 3.6 ± 0.7 | 12.1 |

| PF1741 | [Trehalose/maltose transport protein] | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 10.6 |

| PF1742 | [Trehalose synthase] | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 10.6 |

| PF1784 | ADP-Phosphofructokinase (55) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 5.8 |

| PF1852 | [Glutamate synthase, small] | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 6.1 |

| PF1870 | [Hypothetical protein] | 4.0 ± 1.7 | 16.0 |

| [Maltose transport] | |||

| PF1935 | Amylopullulanase (12) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 4.9 |

| PF1936 | [Sugar transport protein] | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 |

| PF1937 | [Sugar transport protein] | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 6.1 |

| PF1938 | Maltotriose binding protein (15) | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 4.3 |

| PF1951 | [Partial asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase] | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 18.4 |

| PF1975 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 22.6 |

The ORF description is derived either from the annotation (http://comb5-156.umbi.umd.edu/genemate: given within brackets) or from the indicated reference in which there is experimental data to support the ORF assignment specifically in P. furiosus (given without brackets). Potential operons are indicated by bold entries within a group where the intergenic distances are less than 30 nt.

The intensity ratio (maltose/peptide) is expressed as a log2 value so that the standard deviation can be given. For comparison between ORFs, the apparent change in the expression level is also indicated. ORFs are listed that are more than fivefold regulated or that are potentially part of an operon with >fivefold-regulated ORFs but which themselves are regulated by at least threefold. The regulation is statistically significant (P value <0.01) for all ORFs unless otherwise indicated.

Calculated from the average log2 intensity ratio.

The P value ranges from 0.01 to 0.05.

The P values are >0.05.

TABLE 2.

ORFs whose expression is dramatically up-regulated in peptide-grown cells and their potential operon arrangement

| Function and ORF | Descriptiona | Mean intensity ratio (log2 ± SD)a | Change in expression (fold)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| PF0289 | [Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase] | −2.9 ± 0.5 | 7.5 |

| Aminopeptidase | |||

| PF0366 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −1.9 ± 0.5 | 3.7 |

| PF0368 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −1.8 ± 0.3 | 3.5 |

| PF0369 | Deblocking aminopeptidase (54) | −1.8 ± 0.9 | 3.5b |

| PF0370 | [Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase] | −2.6 ± 0.4 | 6.1 |

| PF0477 | Alpha amylase (24) | −2.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 |

| [Cobalt metabolism] | |||

| PF0528 | [Cobalt transport ATP-binding protein] | −2.4 ± 0.7 | 5.3 |

| PF0529 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −2.1 ± 0.8 | 4.3 |

| PF0530 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −1.6 ± 1.1 | 3.0b |

| PF0531 | [Cobalamin biosynthesis protein] | −2.2 ± 0.8 | 4.6 |

| Aryl 2-ketoacid metabolism | |||

| PF0532 | Acetyl-CoA synthetase II alpha (33) | −2.8 ± 0.9 | 7.0 |

| PF0533 | Indolepyruvate Fd oxidoreductase alpha (48) | −2.2 ± 0.6 | 4.6 |

| PF0559 | [Hydrogenase regulatory protein] | −2.4 ± 0.9 | 5.3 |

| PF0612 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −2.8 ± 1.1 | 7.0 |

| PF0613 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (40) | −3.9 ± 0.7 | 15.5 |

| PF0676 | Carbamate kinase (56) | −2.5 ± 0.8 | 5.6 |

| PF0689 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −2.5 ± 1.7 | 5.6d |

| PF0692 | [Prismane] | −3.0 ± 0.8 | 8.0 |

| Hydrogenase I | |||

| PF0891 | Hydrogenase I beta (8) | −3.2 ± 0.7 | 9.2 |

| PF0892 | Hydrogenase I gamma (8) | −3.7 ± 0.8 | 13.0 |

| PF0893 | Hydrogenase I delta (8) | −3.4 ± 0.8 | 10.6 |

| PF0894 | Hydrogenase I alpha (8) | −3.0 ± 0.5 | 8.0 |

| PF0913 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −3.0 ± 0.9 | 8.0 |

| PF0915 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −2.7 ± 2.2 | 6.5b |

| [Acetyl-CoA synthetase] | |||

| PF0972 | [Acyl carrier protein synthase] | −2.4 ± 0.5 | 5.3 |

| PF0973 | [Acetyl CoA synthase] | −2.3 ± 0.9 | 4.9 |

| PF0974 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −2.2 ± 0.6 | 4.6 |

| PF1057 | [Phophoglycerate kinase] | −2.9 ± 1.2 | 7.3 |

| [Amino acid metabolism] | |||

| PF1245 | [d-Nopaline dehydrogenase] | −2.4 ± 1.1 | 5.1 |

| PF1246 | [Sarcosine oxidase, beta] | −2.3 ± 0.7 | 4.9b |

| PF1253 | [Aspartate transaminase] | −2.6 ± 0.7 | 6.1 |

| PF1341 | [Aminomethyltransferase] | −2.9 ± 0.3 | 7.5 |

| 2-Keto acid ferredoxin oxidoreductases | |||

| PF1767 | 2-Ketoglutarate Fd oxidoreductase, delta (48) | −2.9 ± 0.5 | 7.5 |

| PF1768 | 2-Ketoglutarate Fd oxidoreductase alpha (48) | −3.2 ± 0.5 | 9.2 |

| PF1769 | 2-Ketoglutarate Fd oxidoreductase beta (48) | −2.5 ± 0.9 | 5.6 |

| PF1770 | 2-Ketoglutarate Fd oxidoreductase gamma (48) | −3.0 ± 1.0 | 8.0 |

| PF1771 | [2-Ketoacid Fd oxidoreductase, alpha] | −2.7 ± 0.4 | 6.5 |

| PF1772 | [2-Ketoacid Fd oxidoreductase, beta] | −2.4 ± 0.6 | 5.3 |

| PF1773 | [2-Ketoacid Fd oxidoreductase, gamma] | −2.5 ± 0.6 | 5.6 |

| PF1874 | [Glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase] | −3.2 ± 0.8 | 9.3 |

| [Ferredoxin:NADPH oxidoreductase II] | |||

| PF1910 | [Fd NADPH oxidoreductase II] | −4.1 ± 0.8 | 17.1 |

| PF1911 | [Fd NADPH oxidoreductase II] | −3.8 ± 0.7 | 13.9 |

| [Unknown] | |||

| PF2001 | [Conserved hypothetical protein] | −3.6 ± 1.1 | 12.2 |

| PF2002 | [Sucrose transport protein] | −3.4 ± 0.9 | 10.6 |

| PF2047 | [1-Asparaginase] | −2.4 ± 1.0 | 5.3 |

See Table 1 for details.

The P values for these ORFs range from 0.01 to 0.05. For all other ORFs, P < 0.01.

Coordinate regulation of ORF expression.

The ORFs that are up-regulated more than fivefold are listed in Tables 1 and 2 in the order that they are found in the genome. Those that are adjacent to each other with intergenic distances of less than 30 nucleotides are assumed to be coordinately regulated and to be part of the same operon. Remarkably, of the 125 ORFs that are up-regulated, 82 (65%) are part of a total of 27 different operons, 18 affected by maltose and 9 by peptides. That these are operons is supported by the short intergenic distances (compared with distances of >30 nucleotides for the genome in general) and by the proposed (annotated) functions of the ORFs, which in most of the operons are clearly closely related. The notable exceptions are 5 of the 27 operons that encode only (conserved) hypothetical proteins and so their functions cannot be assessed.

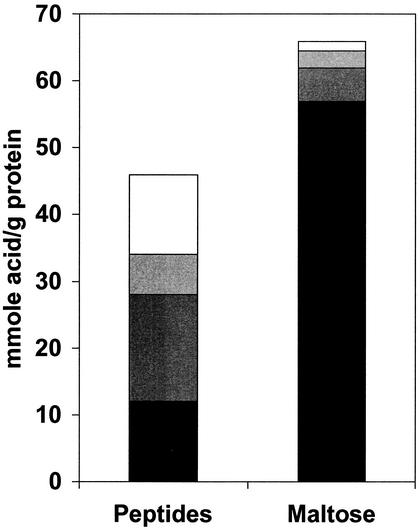

The power of the microarray approach is demonstrated by the fact that the operons that are up-regulated more than fivefold by maltose include those that are responsible for maltose transport and for the biosynthesis of 12 amino acids (Glu, Arg, Leu, Val, Ile, Ser, Thr, Met, His, Phe, Trp, and Try), for ornithine, and for citric acid cycle intermediate products (Table 1). Conversely, operons that are up-regulated in peptide-grown cells include those encoding enzymes involved in the production of acyl and aryl acids and 2-ketoacids from amino acids (Table 2). These data obviously demonstrate significant up-regulation of ORFs involved in biosynthesis of amino acids during growth on maltose, and the data support the proposed pathways for the catabolism of peptide-derived amino acids via transamination and formation of energy-yielding CoA derivatives (1, 33, 48). Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2, analyses of the growth media that were used to obtain the cells that provided the RNA for the microarrays show that a mixture of organic acids, including isovalerate, butyrate, isobutyrate, and phenylacetate, are produced during growth on peptides, whereas acetate is the major product during growth on maltose. These results support a specific switch in regulation in response to a change in the primary carbon source. In the following, we consider the biochemical consequences of the coordinately regulated pathways that are indicated by the microarray analyses.

FIG. 2.

Organic acid production by P. furiosus. Spent media of cells grown by using either peptides or maltose as the carbon source were analyzed for acetate (black), isovalerate (dark gray), (iso)butyrate (light gray), and phenylacetate (white).

Biosynthesis of amino acids in maltose-grown cells.

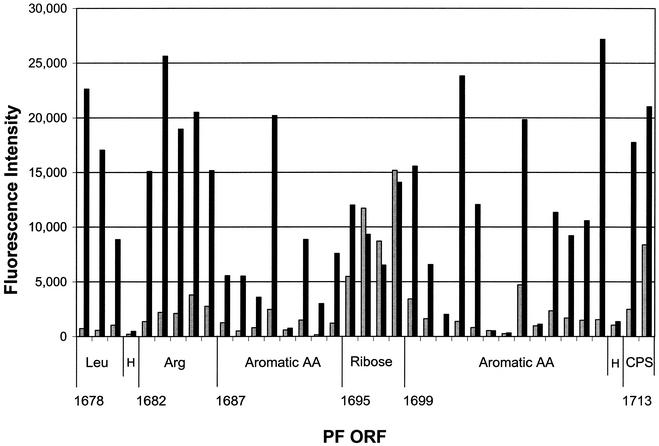

Not only are many of the ORFs involved in amino acid biosynthesis in P. furiosus arranged in operons, but those specific for aromatic amino acids—histidine, ornithine, and branched-chain amino acids—are clustered together in a 51-kb segment (PF1657 to PF1715). As shown in Fig. 3, the majority of the ORFs in this region are up-regulated in maltose-grown cells. In fact, those that are not up-regulated encode proteins involved in ribose transport or are (conserved) hypothetical ORFs. The activity of one of the enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis, acetolactate synthase (PF0935), increased 40-fold in maltose-grown cells (Table 3), in agreement with the measured 17-fold increase in transcript level (Table 1). Carbon for amino acid biosynthesis during growth on maltose appears to be made available in part via three citric acid cycle enzymes: citrate synthase, aconitase, and isocitrate dehydrogenase (PF0201 to PF0203). These presumably supply 2-ketoglutarate for glutamate synthesis and are arranged in an operon that is up-regulated more than fivefold in maltose-grown cultures (Table 1). The activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase is more than twofold higher in maltose-grown cells (Table 3). In agreement with a biosynthetic role for these enzymes, the closely related species Pyrococcus horikoshii and Pyrococcus abyssi, which do not utilize carbohydrates, lack homologs of these three ORFs (2, 23).

FIG. 3.

Relative expression and genome organization of PF1678 to PF1714. The ORFs encoding the subunits of homologs to enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of leucine (Leu), arginine (Arg), aromatic amino acids, and CPS in the transport of ribose (Ribose), and hypothetical (H) ORFs, are indicated. The relative signal intensities are displayed for cDNA obtained from cells grown on peptides (gray bars) or maltose (solid bars).

TABLE 3.

Activities and relative expression levels of key metabolic enzymes

| Enzymea | Peptides (U/mg)d | Maltose (U/mg)d | Ratio (n-fold)d | Peptides (signal intensity)e | Maltose (signal intensity)e | Ratio (fold)f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetolactate synthaseb | 0.0001 ± 0.0001 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | +40 | 1,685 | 28,160 | +17.1 |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenaseb | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.08 | +2.5 | 4,921 | 24,940 | +5.1 |

| GAPDHb | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | −7.0 | 21,051 | 1,967 | −9.3 |

| Amylaseb | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 26.1 ± 8.7 | +5.3 | 1,874 | 30,126 | +26.0 |

| Carbamate kinaseb | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | −1.2 | 19,579 | 3,152 | −5.7 |

| Carbamoyl phosphate synthetaseb | 0.01 ± 0.007 | 0.02 ± 0.009 | +2.0 | 8,382 | 21,041 | +2.3 |

| GAPORc | 0.42 ± 0.38 | 2.25 ± 0.85 | +5.4 | 4,340 | 24,580 | +5.8 |

| GDHc | 5.70 ± 0.67 | 0.73 ± 0.20 | −7.8 | 54,613 | 12,807 | −4.4 |

| PORc | 4.95 ± 1.60 | 4.89 ± 0.87 | 1.0 | 46,512 | 29,744 | −1.5 |

| KGORc | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | −2.2 | 24,841 | 2,654 | −9.4 |

| IORc | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | −12.5 | 33,474 | 7,281 | −4.7 |

| VORc | 1.80 ± 0.61 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | −2.3 | 33,699 | 24,435 | −1.4 |

| ACS Ic | 0.35 ± 0.12 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | −2.3 | 34,988 | 28,575 | −1.2 |

| ACS IIc | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 1.0 | 32,985 | 4,536 | −6.8 |

| PPSc | 1.59 ± 0.09 | 1.02 ± 0.55 | −1.6 | 54,969 | 45,403 | −1.2 |

| H2ase I+IIc | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.10 | −2.4 | 37,936 | 5,102 | −7.8 |

Abbreviations: GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAPOR, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin (Fd) oxidoreductase; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; POR, pyruvate Fd oxidoreductase; KGOR, 2-ketoglutarate Fd oxidoreductase; IOR, indolepyruvate Fd oxidoreductase; VOR, 2-ketoisovalerate Fd oxidoreductase; ACS, acetyl-CoA synthetase; PPS, phosphoenolpyruvate synthetase; H2ase I+II, hydrogenase I and hydrogenase II.

This study.

Taken from reference 1.

Units are defined as micromoles of product formed per minute per milligram of protein. The ratio indicates if they increased (+) or decreased (−) in maltose-grown cells compared to peptide-grown cells.

Average values from eight hybridization experiments carried out in duplicate. Only values for the alpha subunits are given for heteromeric proteins.

The microarray data also shed light on the controversial issue of carbamate metabolism in P. furiosus. Previously, it was proposed that P. furiosus possesses a novel CK (PF0676) that synthesizes carbamoyl phosphate for arginine and pyrimidine biosynthesis (13, 56) rather than its usual physiological role of using carbamoyl phosphate to synthesize ATP. However, the expression of PF0676 is up-regulated (5.7-fold) in peptide-grown cells (Table 2), which is more consistent with the latter energy-conserving role in amino acid catabolism. Moreover, CK is proposed to form a physiological complex with ornithine carbamoyltransferase (PF0594) (34) but ornithine carbamoyltransferase is not significantly regulated by peptides (< twofold). In addition, P. furiosus contains two ORFs (PF1713 and PF1714) that are annotated as (a heterodimeric) CPS. These two ORFs are up-regulated (8.0- and 2.3-fold) in maltose-grown cells, consistent with a role for the enzyme in the biosynthesis of arginine. Further evidence for a traditional role for CK in P. furiosus is its presence in the proteolytic, nonsaccharolytic archaea P. abyssi and P. horikoshii, organisms that do not possess a CPS homolog (2).

New information is also provided by the array data on glutamate metabolism in P. furiosus. For example, the citric acid cycle enzymes (PF0201 to PF0203) that are up-regulated during growth on maltose are adjacent to an operon of three ORFs (PF0204 to PF0206), all of which are also up-regulated by about an order of magnitude. PF0205 is annotated as the large subunit of an NAD-dependent glutamate synthase, an enzyme that catalyzes the reductive transfer of the amine group of glutamine to 2-ketoglutarate, forming glutamate. However, ORFs PF0204 to PF0206 appear to encode subunits of a heterotrimeric, ferredoxin-linked glutamate synthase that is equivalent to the large single-subunit enzymes found in some cyanobacteria (37). This enzyme usually functions in concert with a glutamine synthetase, which forms glutamine from glutamate and ammonia in an ATP-dependent reaction. Accordingly, the putative glutamine synthetase (PF0450) in P. furiosus is up-regulated on maltose by almost 20-fold (Table 1). Interestingly, P. abyssi and P. horikoshii do not possess ORFs corresponding to PF0204 to PF0206, consistent with their inability to grow on maltose in the absence of peptides. P. furiosus also contains a homolog (PF1852) of a novel type of glutamate synthase that has been characterized from another Pyrococcus species (KOD1) (24). This catalyzes the synthesis of glutamate from ammonia and 2-ketoglutarate in an NADPH-dependent reaction. In P. furiosus, expression of PF1852 is up-regulated sixfold in maltose-grown cells, consistent with a role for the enzyme in amino acid biosynthesis.

Transport of carbon growth substrates.

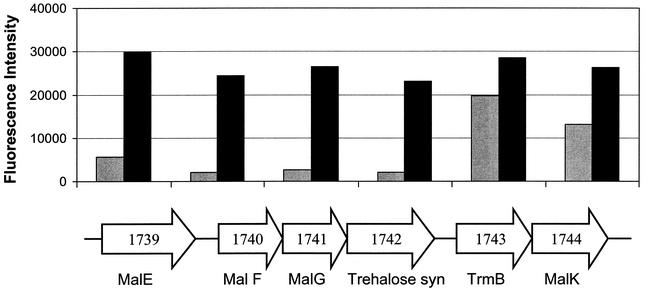

The genome sequence of P. furiosus contains several ORFs that are annotated as peptide transporters of one type or another (PF0191 to PF0194, PF0357 to PF0361, PF0999 to PF1001, and PF1408 to PF1412). However, none of them are up-regulated in peptide-grown cells, suggesting that peptides also can be utilized as a carbon source when P. furiosus is grown in a maltose-containing medium. On the other hand, for maltose uptake, there are two operons that show high sequence similarity to the ORFs in the maltose-trehalose transporter (Mal) operon of the hyperthermophile Thermococcus litoralis (63). Both operons are up-regulated more than fivefold in maltose-grown P. furiosus cells (Table 2). This transport cluster is not found in the genomes of the nonsaccharolytic P. horikoshii and P. abyssi (29; http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/Pab/). The Mal cluster in T. litoralis encodes a maltose binding protein (MalE), two transmembrane proteins (MalF and MalG) and an ATPase subunit (MalK) (63), together with a maltose-specific transcriptional regulator, TrmB, and an ORF annotated as a trehalose synthase (29). An almost exact copy (even on the nucleotide level) of the Mal cluster in T. litoralis is present in P. furiosus (Fig. 4), and this is thought to have arisen by horizontal gene transfer between the two organisms (11). The microarray data indicate that the Mal (I) cluster in P. furiosus is divided into three transcriptional units: MalE, MalFG-trehalose synthase, and TrmB-MalK (Fig. 4). The finding of significant amounts of the MalE and TrmB-MalK transcripts in maltose-grown P. furiosus cells (Fig. 4) is in agreement with the report that the MalK and MalE proteins can be detected in T. litoralis cells grown in the absence of maltose (17) and that TrmB represses the synthesis of the MalEFG-trehalose synthase cluster (29). However, although P. furiosus converts maltose into glucose (63), no obvious candidate for an α-glucosidase has been identified in the genome. A protein with α-glucosidase activity was purified from P. furiosus, but sequence information was not obtained (9). A likely candidate for at least one maltose-utilizing enzyme is the putative trehalose synthase, which contains glucanotransferase motifs and is present in the Mal I cluster.

FIG. 4.

Relative expression of ORFs of the Mal I operon in the presence of peptides or maltose. The six ORFs encoding the subunits of the maltose transporter I are arranged according to their genome positions. The relative signal intensities for cDNA obtained from cells grown on peptides (gray bars) or maltose (solid bars) are indicated (actual values with standard deviations are given in Table 2).

Interestingly, the second maltose transporter (Mal II) cluster in P. furiosus (PF1938 to PF1933) is also up-regulated in maltose-grown cells and is organized in a fashion similar to that of Mal I with three transcription units, except that the ORF adjacent to MalG is annotated as an amylopullulanase (12) rather than as a trehalose synthase. The two Mal clusters are probably induced by maltose and/or malto-oligosaccharides, and their gene products presumably work together to metabolize these sugars as well as others derived from starch. In fact, the expression of an α-amylase (PF0272) (27) is up-regulated 26-fold in maltose-grown cultures, consistent with the high α-amylase activity measured in such cells (Table 3). However, peptide-grown cells still contain significant α-amylase activity (Table 3). This is assumed to arise from the product of PF0477, which is also annotated as an α-amylase (25) and is up-regulated 5.3-fold in peptide-grown cells (Table 2). A homolog of this enzyme is present neither in the genome of P. horikoshii nor in that of P. abyssi (2), and this enzyme presumably generates oligosaccharides that then induce the complete saccharolytic pathways when polysaccharides become available during peptide-dependent growth.

Glucose metabolism.

Unlike ORFs that encode some of the enzymes involved with maltose metabolism, ORFs encoding glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes are unlinked in the genome. Their relative transcript levels under the two growth conditions are shown in Table 4. Three of them that are unique to the glycolytic pathway, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (PGI), ADP phophofructokinase (PFK), and GAPOR, are strongly up-regulated in maltose-grown cells. This was previously shown for PGI and GAPOR (58, 60), and the increase in the transcript level of GAPOR is in agreement with the measured increase in enzyme activity (Table 3). Interestingly, glucokinase, which is thought to have arisen from PFK by gene duplication (55), is not regulated, and significant amounts of the transcript are found in peptide-grown cells (Table 4). Conversely, three enzymes unique to gluconeogenesis, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBPase), PGK, and GAPDH, are all up-regulated in peptide-grown cells (Table 4). The increase in the transcript level of GAPDH in peptide-grown cells is in agreement with the observed increase in enzyme activity (Table 3). FBPase (PF0613) is up-regulated 15-fold in peptide-grown cells, and this corresponds to the FBPase proposed by Rashid et al. (40). The other FBPase candidate (F2014) (59) is not significantly regulated and is therefore unlikely to play a gluconeogenic role. FBA was reported to be up-regulated in maltose-grown cells relative to those grown on pyruvate (51), but such regulation is not observed here in peptide-grown cells (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Relative expression of genes involved in glucose catabolism and synthesis

| Function and ORFa | Descriptiona | Mean intensity ratio (log2 ± SD)a,b | Relative expression (maltose/peptide)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | |||

| PF0312 | ADP-glucokinase (26) | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 27/13 |

| PF0196 | Glucose-6-P isomerase (19) | +2.3 ± 0.4 | 17/4 |

| PF1784 | ADP-phosphofructokinase (55) | +2.5 ± 0.5 | 27/5 |

| PF0464 | Glyceraldehyde-3-P Fd oxidoreductase (36) | +2.5 ± 0.5 | 25/4 |

| PF1188 | [Pyruvate kinase] | −0.6 ± 0.6 | 4/6 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | |||

| PF1956 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (51) | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 25/23 |

| PF1959 | Phosphoglycerate mutase (57) | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 28/8 |

| PF0215 | Enolase (39) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 25/11 |

| PF0971 | Pyruvate Fd oxidoreductase gamma (48) | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 32/29 |

| PF0967 | Pyruvate Fd oxidoreductase delta (48) | −0.7 ± 0.5 | 26/41 |

| PF0966 | Pyruvate Fd oxidoreductase alpha (48) | −0.7 ± 0.3 | 29/46 |

| PF0965 | Pyruvate Fd oxidoreductase beta (48) | −0.5 ± 0.3 | 31/45 |

| PF1540 | Acetyl-CoA synthetase alpha (33) | −0.3 ± 0.4 | 29/35 |

| PF1787 | Acetyl-CoA synthetase beta (33) | −0.6 ± 0.3 | 21/32 |

| PF1920 | Triosephosphate isomerase | +2.2 ± 0.6 | 21/4 |

| Gluconeogenesis | |||

| PF0043 | Phosphoenolpyruvate synthetase (22) | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 34/31 |

| PF0613 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (40) | −3.9 ± 0.7 | 3/36 |

| PF1874 | [Glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase] | −3.2 ± 0.8 | 2/21 |

| PF1057 | [Phosphoglycerate kinase] | −2.9 ± 1.2 | 1/8 |

See Table 1 for details.

ORFs that are significantly up (+) or down (−) regulated in the presence of maltose are indicated in bold (P values <0.01).

Relative expression is signal intensity in peptide-grown cells/signal intensity in maltose-grown cells divided by 1,000 for each ORF (16 data points).

One would not expect the remaining 13 ORFs that encode glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzymes to be regulated, but this is indeed the case (Table 4)—with one notable exception. Triosephosphate isomerase is apparently up-regulated almost fivefold in maltose-grown cells for reasons that are not clear at present. Both pyruvate kinase and its gluconeogenic counterpart, phosphoenolpyruvate synthetase (PPS), are each expressed at comparable levels under the two types of growth condition (Table 4), and this was confirmed for PPS with activity measurements (Table 3). PPS is one of the most abundant enzymes in P. furiosus, although the function of the enzyme in maltose-grown cells is not obvious (22, 44). Two other highly expressed enzymes involved in glucose catabolism are POR and ACS I. Like PPS, neither the array data (Table 4) nor the activity measurements (Table 3) indicate significant regulation of either enzyme. This is expected, since POR and ACS I also play key roles in energy conservation in peptide metabolism by using pyruvate derived from amino acid catabolism.

Amino acid catabolism.

The first step in the utilization of amino acids in peptide-grown cells is thought to involve transamination (48) and, accordingly, several transaminases are up-regulated. They include one yet to be characterized, PF1253 (6.1-fold) and two that have been purified, PF0121 (4.5-fold) (3) and PF1497 (2.5-fold) (62). These transamination reactions produce various 2-ketoacids as well as glutamate from 2-ketoglutarate. Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) serves to regenerate the 2-ketoglutarate, and the expression of its gene also increases significantly (4.4-fold) in peptide-grown cells (see supplemental material [http://adams.bomb.uga.edu/pubs/sup238.pdf]). The 2-ketoacids are oxidized by four distinct 2-ketoacid ferredoxin oxidoreductases (KORs) that have been characterized from P. furiosus (48). Two of them, which are specific for 2-ketoglutarate (KGOR; PF1767 to PF1770) and for 2-ketoacids derived from aromatic amino acids (IOR; PF0533 to 0534), are up-regulated in peptide-grown cultures (Table 2). The other two, which utilize pyruvate (POR) and 2-ketoacids derived from the branched-chain amino acids (VOR), are expressed at high levels in peptide-grown as well as in maltose-grown cells. This is expected for POR, as it also uses pyruvate produced from glycolysis during growth on maltose, but the function of VOR in maltose-grown cells is unclear. In any event, the activities of VOR, IOR, KGOR, and POR in cell extracts correspond well with the expression levels determined by the array analyses (Table 3). However, KGOR has been purified (48) and is composed of four different subunits (PF1767 to PF1770), but the KGOR operon contains three additional ORFs, and these encode homologs of the KGOR subunits (PF1771 to PF1773). All three ORFs are coregulated with the four ORFs of KGOR in peptide-grown cells and presumably encode a fifth member of the KOR family with as-yet-unknown substrate specificity (Table 2).

The CoA derivatives generated by the KORs are used to conserve energy by ACS I and ACS II. These enzymes have both been purified and they utilize acyl- and aryl-CoAs, respectively. Although ACS I (PF1540 and PF1787) is not dramatically regulated by the carbon source, the expression of the alpha subunit (PF0532) of ACS II increases more than fivefold in peptide-grown cells, although the expression of its beta subunit (PF1837) is unaffected, as is its activity in cell extracts (Table 3). Rationalizing such data is not trivial, as the genome contains three more homologs of the alpha subunit of ACS II (PF0233, PF1085, and PF1838), none of which are significantly regulated, and their corresponding beta subunits cannot be identified. Clearly, the nature and role of the ACS family of enzymes is complex, and more biochemical analyses are needed to complement the array data.

During amino acid catabolism, reductant is generated both as reduced ferredoxin from the KORs and as NAD(P)H from GDH. These are interconverted by ferredoxin NAD(P) oxidoreductase (FNOR), an enzyme previously characterized from P. furiosus (31). Surprisingly, the expression of the two subunits of FNOR (PF1327 and PF1328) are both down-regulated more than fivefold in peptide-grown cells (Table 1), yet FNOR activity is largely unaffected (1). However, the genome contains two ORFs (PF1901 and PF1911) that appear to be close homologs of the two FNOR subunits, and their expression increased by more than an order of magnitude in peptide-grown cells, presumably in a compensatory fashion (Table 2). It therefore seems reasonable to conclude that the interconversion of NAD(P)H and ferredoxin is catalyzed by two distinct FNORs (I and II), the expression of which is dependent upon the carbon source. FNOR was also referred to as sulfide dehydrogenase because of its ability to reduce S0 in vitro (31). Indeed, PF1901 and PF1911 have been referred to by Hagen and coworkers as subunits (SudXY) of a second sulfide dehydrogenase based on sequence analyses (18). However, S0 metabolism in P. furiosus involves a novel system unrelated to the two FNOR enzymes (49), and the designation SudXY is inappropriate for the subunits of what is referred to here as FNOR II (Table 2).

Finally, the microarray data also provide intriguing information on one other class of enzyme, the hydrogenases. Previous studies have shown both the expression and the activities of the two cytoplasmic and one membrane-bound hydrogenases of P. furiosus dramatically decrease in maltose-grown cultures when S0 is present (1, 49). To our surprise, however, transcript levels of the four subunits of hydrogenase I all increase by about an order of magnitude in peptide-grown cultures (in the presence of S0; Table 2), even though the hydrogenase activity in the cell extracts remained very low (1). In fact, the expression of the hydrogenase maturation protein HypF (PF0559) is also up-regulated fivefold in peptide-grown cells, so lack of this protein should not prevent formation of active hydrogenase I (Table 2). On the other hand, as expected, transcripts for the four subunits of hydrogenase II could not be detected in peptide-grown cells, and no significant up-regulation of the membrane-bound hydrogenase was observed. It is not clear why hydrogenase I appears to be up-regulated in peptide-grown cells, especially without a corresponding increase in activity, and this phenomenon is currently under study.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM 60329), the National Science Foundation (MCB 0129841, MCB 9904624, and BES-0004257), and the Department of Energy (FG05-95ER20175).

We thank Frank E. Jenney, Jr., Angeli Lal Menon, James F. Holden, Eleanor Green, and Rajat Sapra for many helpful discussions, Farris Poole for bioinformatic analyses, Patrick Lynch and Todd Twiss for assistance with the acid analyses, and Frank T. Robb for providing access to preliminary information from the P. furiosus genome sequencing project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. W. W., J. F. Holden, A. L. Menon, G. J. Schut, A. M. Grunden, C. Hou, A. M. Hutchins, F. E. Jenney, Jr., C. Kim, K. Ma, G. Pan, R. Roy, R. Sapra, S. V. Story, and M. F. Verhagen. 2001. Key role for sulfur in peptide metabolism and in regulation of three hydrogenases in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:716-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreotti, G., M. V. Cubellis, G. Nitti, G. Sannia, X. Mai, M. W. Adams, and G. Marino. 1995. An extremely thermostable aromatic aminotransferase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1247:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baliga, N. S., M. Pan, Y. A. Goo, E. C. Yi, D. R. Goodlett, K. Dimitrov, P. Shannon, R. Aebersold, W. V. Ng, and L. Hood. 2002. Coordinate regulation of energy transduction modules in Halobacterium sp. analyzed by a global systems approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14913-14918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbier, G., A. Godfroy, J. R. Meunier, J. Querellou, M. A. Cambon, F. Lesongeur, P. A. Grimont, and G. Raguenes. 1999. Pyrococcus glycovorans sp. nov., a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from the East Pacific Rise. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt. 4):1829-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blamey, J., M. Chiong, C. Lopez, and E. Smith. 1999. Optimization of the growth conditions of the extremely thermophilic microorganisms Thermococcus celer and Pyrococcus woesei. J. Microbiol. Methods 38:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyde, T. R., and M. Rahmatullah. 1980. Optimization of conditions for the colorimetric determination of citrulline, using diacetyl monoxime. Anal. Biochem. 107:424-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant, F. O., and M. W. W. Adams. 1989. Characterization of hydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium. Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 264:5070-5079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costantino, H. R., S. H. Brown, and R. M. Kelly. 1990. Purification and characterization of an α-glucosidase from a hyperthermophilic archaebacterium, Pyrococcus furiosus, exhibiting a temperature optimum of 105 to 115°C. J. Bacteriol. 172:3654-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Saizieu, A., C. Gardes, N. Flint, C. Wagner, M. Kamber, T. J. Mitchell, W. Keck, K. E. Amrein, and R. Lange. 2000. Microarray-based identification of a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae regulon controlled by an autoinduced peptide. J. Bacteriol. 182:4696-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diruggiero, J., D. Dunn, D. L. Maeder, R. Holley-Shanks, J. Chatard, R. Horlacher, F. T. Robb, W. Boos, and R. B. Weiss. 2000. Evidence of recent lateral gene transfer among hyperthermophilic archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 38:684-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong, G., C. Vieille, and J. G. Zeikus. 1997. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene encoding amylopullulanase from Pyrococcus furiosus and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3577-3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durbecq, V., C. Legrain, M. Roovers, A. Pierard, and N. Glansdorff. 1997. The carbamate kinase-like carbamoyl phosphate synthetase of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus, a missing link in the evolution of carbamoyl phosphate biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12803-12808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durst, H. D., M. Milano, E. J. Kikta, Jr., S. A. Connelly, and E. Grushka. 1975. Phenacyl esters of fatty acids via crown ether catalysts for enhanced ultraviolet detection in liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem. 47:1797-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evdokimov, A. G., D. E. Anderson, K. M. Routzahn, and D. S. Waugh. 2001. Structural basis for oligosaccharide recognition by Pyrococcus furiosus maltodextrin-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol. 305:891-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiala, G., and K. O. Stetter. 1986. Pyrococcus furiosus sp. nov. represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100°C. Arch. Microbiol. 145:56-61. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greller, G., R. Horlacher, J. DiRuggiero, and W. Boos. 1999. Molecular and biochemical analysis of MalK, the ATP-hydrolyzing subunit of the trehalose/maltose transport system of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:20259-20264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagen, W. R., P. J. Silva, M. A. Amorim, P. L. Hagedoorn, H. Wassink, H. Haaker, and F. T. Robb. 2000. Novel structure and redox chemistry of the prosthetic groups of the iron-sulfur flavoprotein sulfide dehydrogenase from Pyrococcus furiosus; evidence for a [2Fe-2S] cluster with Asp(Cys)3 ligands. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 5:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen, T., M. Oehlmann, and P. Schonheit. 2001. Novel type of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:3428-3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hihara, Y., A. Kamei, M. Kanehisa, A. Kaplan, and M. Ikeuchi. 2001. DNA microarray analysis of cyanobacterial gene expression during acclimation to high light. Plant Cell 13:793-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holm, S. 1979. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Statist. 6:65-70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchins, A. M., J. F. Holden, and M. W. W. Adams. 2001. Phosphoenolpyruvate synthetase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 183:709-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huynen, M. A., T. Dandekar, and P. Bork. 1999. Variation and evolution of the citric-acid cycle: a genomic perspective. Trends Microbiol. 7:281-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jongsareejit, B., R. N. Rahman, S. Fujiwara, and T. Imanaka. 1997. Gene cloning, sequencing and enzymatic properties of glutamate synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus sp. KOD1. Mol. Gen. Genet. 254:635-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgensen, S., C. E. Vorgias, and G. Antranikian. 1997. Cloning, sequencing, characterization, and expression of an extracellular alpha-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16335-16342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kengen, S. W., J. E. Tuininga, F. A. de Bok, A. J. Stams, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Purification and characterization of a novel ADP-dependent glucokinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 270:30453-30457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laderman, K. A., K. Asada, T. Uemori, H. Mukai, Y. Taguchi, I. Kato, and C. B. Anfinsen. 1993. Alpha-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Cloning and sequencing of the gene and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24402-24407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laderman, K. A., B. R. Davis, H. C. Krutzsch, M. S. Lewis, Y. V. Griko, P. L. Privalov, and C. B. Anfinsen. 1993. The purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable alpha-amylase from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 268:24394-24401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, S. J., A. Engelmann, R. Horlacher, Q. Qu, G. Vierke, C. Hebbeln, M. Thomm, and W. Boos. 2002. TrmB, a sugar-specific transcriptional regulator of the trehalose/maltose ABC transporter from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. J. Biol. Chem. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Legrain, C., V. Villeret, M. Roovers, C. Tricot, B. Clantin, J. Van Beeumen, V. Stalon, and N. Glansdorff. 2001. Ornithine carbamoyltransferase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Methods Enzymol. 331:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma, K., and M. W. W. Adams. 2001. Ferredoxin NADP oxidoreductase from Pyrococcus furiosus. Methods Enzymol. 334:40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma, K., and M. W. W. Adams. 1994. Sulfide dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: a new multifunctional enzyme involved in the reduction of elemental sulfur. J. Bacteriol. 176:6509-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mai, X., and M. W. W. Adams. 1996. Purification and characterization of two reversible and ADP-dependent acetyl coenzyme A synthetases from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 178:5897-5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massant, J., P. Verstreken, V. Durbecq, A. Kholti, C. Legrain, S. Beeckmans, P. Cornelis, and N. Glansdorff. 2002. Metabolic channeling of carbamoyl phosphate, a thermolabile intermediate: evidence for physical interaction between carbamate kinase-like carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase and ornithine carbamoyltransferase from the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18517-18522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muir, J. M., R. J. Russell, D. W. Hough, and M. J. Danson. 1995. Citrate synthase from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. Protein Eng. 8:583-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukund, S., and M. W. W. Adams. 1995. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, a novel tungsten-containing enzyme with a potential glycolytic role in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 270:8389-8392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro, F., E. Martin-Figueroa, P. Candau, and F. J. Florencio. 2000. Ferredoxin-dependent iron-sulfur flavoprotein glutamate synthase (GlsF) from the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: expression and assembly in Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 379:267-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh, M. K., and J. C. Liao. 2000. Gene expression profiling by DNA microarrays and metabolic fluxes in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Prog. 16:278-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peak, M. J., J. G. Peak, F. J. Stevens, J. Blamey, X. Mai, Z. H. Zhou, and M. W. W. Adams. 1994. The hyperthermophilic glycolytic enzyme enolase in the archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus: comparison with mesophilic enolases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 313:280-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rashid, N., H. Imanaka, T. Kanai, T. Fukui, H. Atomi, and T. Imanaka. 2002. A novel candidate for the true fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 277:30649-30655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rinderknecht, H., E. P. Marbach, C. R. Carmack, C. Conteas, and M. C. Geokas. 1971. Clinical evaluation of an α-amylase assay with insoluble starch labeled with Remazolbrilliant Blue (amylopectin-azure). Clin. Biochem. 4:162-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robb, F. T., D. L. Maeder, J. R. Brown, J. DiRuggiero, M. D. Stump, R. K. Yeh, R. B. Weiss, and D. M. Dunn. 2001. Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus: implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 330:134-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross, D. T., U. Scherf, M. B. Eisen, C. M. Perou, C. Rees, P. Spellman, V. Iyer, S. S. Jeffrey, M. Van de Rijn, M. Waltham, A. Pergamenschikov, J. C. Lee, D. Lashkari, D. Shalon, T. G. Myers, J. N. Weinstein, D. Botstein, and P. O. Brown. 2000. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nat. Genet. 24:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakuraba, H., E. Utsumi, C. Kujo, and T. Ohshima. 1999. An AMP-dependent (ATP-forming) kinase in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: characterization and novel physiological role. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 364:125-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sapra, R., M. F. Verhagen, and M. W. W. Adams. 2000. Purification and characterization of a membrane-bound hydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 182:3423-3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schafer, T., and P. Schonheit. 1993. Gluconeogenesis from pyruvate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus—involvement of reactions of the Embden-Meyerhof pathway. Arch. Microbiol. 159:354-363. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schena, M., D. Shalon, R. W. Davis, and P. O. Brown. 1995. Quantitative monitoring of gene-expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science 270:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schut, G. J., A. L. Menon, and M. W. W. Adams. 2001. 2-ketoacid oxidoreductases from Pyrococcus furiosus and Thermococcus litoralis. Methods Enzymol. 331:144-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schut, G. J., J. Zhou, and M. W. W. Adams. 2001. DNA microarray analysis of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: evidence for a new type of sulfur-reducing enzyme complex. J. Bacteriol. 183:7027-7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selig, M., K. B. Xavier, H. Santos, and P. Schonheit. 1997. Comparative analysis of Embden-Meyerhof and Entner-Doudoroff glycolytic pathways in hyperthermophilic archaea and the bacterium Thermotoga. Arch. Microbiol. 167:217-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siebers, B., H. Brinkmann, C. Dorr, B. Tjaden, H. Lilie, J. van der Oost, and C. H. Verhees. 2001. Archaeal fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolases constitute a new family of archaeal type class I aldolase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:28710-28718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steen, I. H., D. Madern, M. Karlstrom, T. Lien, R. Ladenstein, and N. K. Birkeland. 2001. Comparison of isocitrate dehydrogenase from three hyperthermophiles reveals differences in thermostability, cofactor specificity, oligomeric state, and phylogenetic affiliation. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43924-43931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stetter, K. O. 1999. Extremophiles and their adaptation to hot environments. FEBS Lett. 452:22-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsunasawa, S., S. Nakura, T. Tanigawa, and I. Kato. 1998. Pyrrolidone carboxyl peptidase from the hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus: cloning and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the gene, and its application to protein sequence analysis. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 124:778-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuininga, J. E., C. H. Verhees, J. van der Oost, S. W. Kengen, A. J. Stams, and W. M. de Vos. 1999. Molecular and biochemical characterization of the ADP-dependent phosphofructokinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21023-21028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uriarte, M., A. Marina, S. Ramon-Maiques, I. Fita, and V. Rubio. 1999. The carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase of Pyrococcus furiosus is enzymologically and structurally a carbamate kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:16295-16303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Oost, J., M. A. Huynen, and C. H. Verhees. 2002. Molecular characterization of phosphoglycerate mutase in archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Oost, J., G. Schut, S. W. Kengen, W. R. Hagen, M. Thomm, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. The ferredoxin-dependent conversion of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus represents a novel site of glycolytic regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 273:28149-28154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Verhees, C. H., J. Akerboom, E. Schiltz, W. M. de Vos, and J. van der Oost. 2002. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a distinct type of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 184:3401-3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verhees, C. H., M. A. Huynen, D. E. Ward, E. Schiltz, W. M. de Vos, and J. van der Oost. 2001. The phosphoglucose isomerase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus is a unique glycolytic enzyme that belongs to the cupin superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40926-40932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Voorhorst, W. G., R. I. Eggen, E. J. Luesink, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Characterization of the celB gene coding for β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus and its expression and site-directed mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:7105-7111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward, D. E., S. W. Kengen, J. van Der Oost, and W. M. de Vos. 2000. Purification and characterization of the alanine aminotransferase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus and its role in alanine production. J. Bacteriol. 182:2559-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xavier, K. B., R. Peist, M. Kossmann, W. Boos, and H. Santos. 1999. Maltose metabolism in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis: purification and characterization of key enzymes. J. Bacteriol. 181:3358-3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xing, R. Y., and W. B. Whitman. 1987. Sulfometuron methyl-sensitive and -resistant acetolactate synthases of the archaebacteria Methanococcus spp. J. Bacteriol. 169:4486-4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ye, R. W., W. Tao, L. Bedzyk, T. Young, M. Chen, and L. Li. 2000. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 182:4458-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]