Abstract

The covalent modification of proteins by ubiquitination is a major regulatory mechanism of protein degradation and quality control, endocytosis, vesicular trafficking, cell-cycle control, stress response, DNA repair, growth-factor signalling, transcription, gene silencing and other areas of biology. A class of specific ubiquitin-binding domains mediates most of the effects of protein ubiquitination. The known membership of this group has expanded rapidly and now includes at least sixteen domains: UBA, UIM, MIU, DUIM, CUE, GAT, NZF, A20 ZnF, UBP ZnF, UBZ, Ubc, UEV, UBM, GLUE, Jab1/MPN and PFU. The structures of many of the complexes with mono-ubiquitin have been determined, revealing interactions with multiple surfaces on ubiquitin. Inroads into understanding polyubiquitin specificity have been made for two UBA domains, whose structures have been characterized in complex with Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin. Several ubiquitin-binding domains, including the UIM, CUE and A20 ZnF (zinc finger) domains, promote auto-ubiquitination, which regulates the activity of proteins that contain them. At least one of these domains, the A20 ZnF, acts as a ubiquitin ligase by recruiting a ubiquitin–ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme thiolester adduct in a process that depends on the ubiquitin-binding activity of the A20 ZnF. The affinities of the mono-ubiquitin-binding interactions of these domains span a wide range, but are most commonly weak, with Kd>100 μM. The weak interactions between individual domains and mono-ubiquitin are leveraged into physiologically relevant high-affinity interactions via several mechanisms: ubiquitin polymerization, modification multiplicity, oligomerization of ubiquitinated proteins and binding domain proteins, tandem-binding domains, binding domains with multiple ubiquitin-binding sites and co-operativity between ubiquitin binding and binding through other domains to phospholipids and small G-proteins.

Keywords: endocytosis, proteasome, protein structure, ubiquitination, ubiquitin-binding domain, vesicle trafficking

Abbreviations: CUE, coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to endoplasmic reticulum degradation; DUIM, double-sided ubiquitin-interacting motif; ESCRT, endosomal sorting complexes required for transport; GAT, GGA and TOM; GGA, Golgi-localized, gamma-ear-containing, ADP-ribosylation-factor-binding protein; GLUE, GRAM-like ubiquitin binding in EAP45; MIU, motif interacting with ubiquitin; NZF, Npl4 zinc finger; PAZ, polyubiquitin-associated zinc binding; PFU, PLAA family ubiquitin binding; PH, pleckstrin homology; RIP, receptor-interacting protein; TOM, target of Myb; UBA, ubiquitin-associated; Ubc, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; UBM, ubiquitin-binding motif; UBP, ubiquitin-specific processing protease; UBZ, ubiquitin-binding zinc finger; UEV, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant; UIM, ubiquitin-interacting motif; Vps, vacuolar sorting protein; ZnF, zinc finger

UBIQUITIN AND PROTEIN UBIQUITINATION

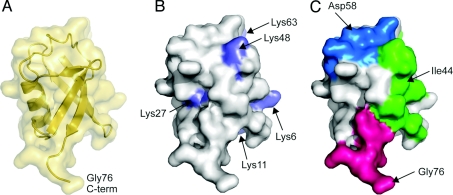

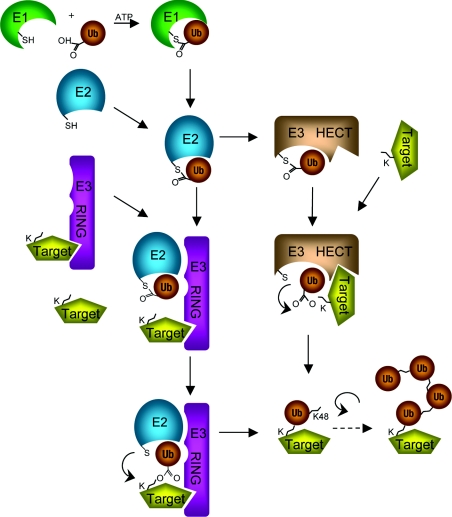

Ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid protein (Figure 1), so-named for its extraordinarily wide distribution from yeast to man [1]. The covalent ubiquitination of proteins is a widespread regulatory post-translational modification, much like protein phosphorylation. The C-terminus of ubiquitin is conjugated to lysine residues of target proteins by the action of three enzymes: an ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and an ubiquitin protein ligase (E3) (Figure 2) [1–4]. Ubiquitin is conjugated to proteins via an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of ubiquitin and specific lysine residues in the ubiquitinated protein. Ubiquitin may be attached to proteins as a monomer or as a polyubiquitin chain. Ubiquitin polymers are formed when additional ubiquitin molecules are attached to lysine residues on a previously attached ubiquitin.

Figure 1. Structural features of ubiquitin.

(A) Ribbon and surface representations of ubiquitin (Protein data bank identication code: 1UBQ). The C-terminal Gly76 is marked. (B) Location of lysine residues (blue) on ubiquitin. The ubiquitin molecule is shown as surface representation. (C) Major recognition patches on ubiquitin. The hydrophobic patch centred on Ile44 (green), the polar patch centred on Asp58 (blue) and the diglycine patch near the C-terminal Gly76 (pink) are shown.

Figure 2. Major enzymatic pathways of protein ubiquitination.

HECT, homologous to E6AP C-terminus; K, lysine; RING, really interesting new gene; Ub, ubiquitin.

Early interest in ubiquitination centred on the role of polyubiquitin chains in targeting proteins for degradation by the 26 S proteasome [5,6]. We now know that ubiquitination regulates a much wider array of cell processes, including endocytosis, vesicular trafficking [7–9], cell-cycle control, stress response, DNA repair [10], signalling [11,12], transcription and gene silencing. Recent progress in the discovery of new biological roles for ubiquitination has gone hand in hand with the discovery of a host of ubiquitin-binding domains [13,14] (Table 1). The characterization of these domains has become a major foundation for advancing the biology of ubiquitin-based regulatory mechanisms.

Table 1. Complex structures and binding affinities of ubiquitin-binding domains.

The Kd values are for mono-ubiquitin unless otherwise specified. Protein data bank identification codes (PDB ID) (http://www.rcsb.org) are only listed for co-ordinates containing ubiquitin-binding domains complexed with ubiquitin unless otherwise specified. ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; Ub, ubiquitin.

| Binding affinity | Structure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ub-binding domain | Source protein | Kd (μM) | Method | PDB ID | Method (resolution, Å) | Note | Reference |

| UBA | Dsk2 | 14.8±5.3 | SPR | 1WR1 | NMR | [47] | |

| hHR23A | 400±100 (mono-Ub) | NMR | 1ZO6 | NMR | UBA2–two Ub | [48] | |

| Mud1 | 390±50 (mono-Ub) | SPR | 1Z96 | X-ray (1.8) | PDB for UBA alone | [55] | |

| Ede1 | 83±9 | NMR | 2G3Q | NMR | [49] | ||

| CUE | Vps9 | 20±1 | ITC | 1P3Q | X-ray (1.7) | Dimeric CUE | [52] |

| Cue2 | 155±9 | NMR | 1OTR | NMR | Monomeric CUE | [53] | |

| GAT | GGA3 | 181±39 | ITC | 1YD8 | X-ray (2.8) | Two Ub-binding sites; Ub binds to site 1 in the crystal structure | [72] |

| GGA3 | 1WR6 | X-ray (2.6) | [73] | ||||

| TOM1 | 409±13 | SPR | 1WRD | X-ray (1.75) | [74] | ||

| UEV | Vps23 | 1UZX | X-ray (1.85) | [88] | |||

| Tsg101 | 510±35 | SPR | 1S1Q | X-ray (2.0) | [87,89] | ||

| Ubc | UbcH5 | ∼300 | NMR | 2FUH | NMR | [90] | |

| UIM | Vps27 | 277±8 (UIM1) | NMR | 1Q0W | NMR | UIM1–Ub | [27] |

| 177±17 (UIM2) | |||||||

| Vps27 | 246±1 (UIM1) | SPR | 1O06 | X-ray (1.45) | UIM2 only; no Ub | [26] | |

| 1690±40 (UIM2) | |||||||

| S5a | ∼350 (UIM1) | NMR | 1YX5 | NMR | [29] | ||

| S5a | 73 (UIM2) | NMR | 1YX6 | NMR | [28,29] | ||

| DUIM | Hrs | 190 (wt) | SPR | 2D3G | X-ray | Two Ub-binding sites | [32] |

| 491 (site 1) | |||||||

| 543 (site 2) | |||||||

| MIU | Rabex-5 | 29±4.8 (Y25A, SPR) | SPR, ITC | 2FID, 2FIF | X-ray (2.5) | [30] | |

| 29±1 (Y26A, ITC) | |||||||

| 28.7 | ITC | 2C7N | X-ray (2.1) | [31] | |||

| NZF | Npl4 | 126±26 | SPR | 1Q5W | NMR | [79] | |

| A20 ZnF | Rabex-5 | 22±0.4 (A58D, SPR) | SPR, ITC | 2FID, 2FIF | X-ray (2.5) | [30] | |

| 21±1 (A58D, ITC) | |||||||

| Rabex-5 | 12 | ITC | 2C7N | X-ray (2.1) | [31] | ||

| ZnF UBP | Isopeptidase T | 2.8 | ITC | 2G45 | X-ray (2.0) | [82] | |

UBIQUITIN-BINDING DOMAINS: STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

Helical domains

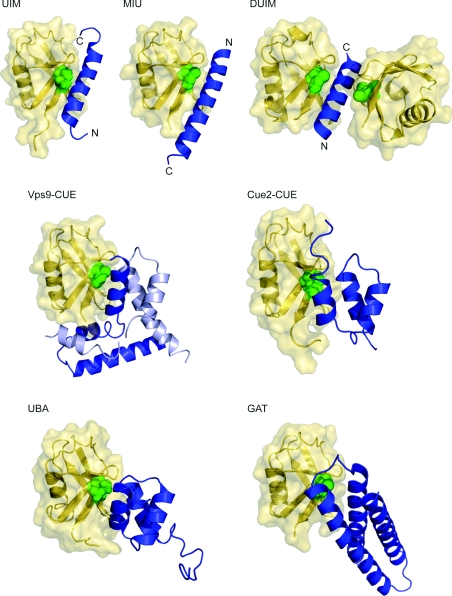

The largest class of ubiquitin-binding domains are α-helical: UBA (ubiquitin associated), UIM (ubiquitin-interacting motif), DUIM (double-sided UIM), MIU (motif interacting with ubiquitin), CUE (coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to endoplasmic reticulum degradation) and GAT [GGA (Golgi-localized, gamma-ear-containing, ADP-ribosylation-factor-binding protein) and TOM (target of Myb)]. All of the helical ubiquitin-binding domains are known to interact with a single region on ubiquitin, the Ile44 hydrophobic patch. The UBA and CUE domains have structural homology, with a common three-helical bundle architecture. They also have similar modes of binding to the Ile44 patch. The UIM and GAT domain structures are unrelated, except for being helical, and they interact with this patch in different ways (Figure 3). The otherwise unrelated octahelical VHS [Vps (vacuolar sorting protein) 27/Hrs/STAM] domain has also been reported to bind to ubiquitin [15].

Figure 3. Helical ubiquitin-binding domain structures.

Ubiquitin molecule (yellow) in ribbon and surface representations is shown with corresponding helical domain (blue) in ribbon representation. Ile44, the centre of the hydrophobic recognition patch on the ubiquitin, is shown as green spheres. Ubiquitin molecules are placed in the same orientation as in Figure 1 for comparison. For the UIM, MIU and DUIM structures, both N- and C-termini are marked. Protein data bank identication codes used are as follows: UIM, 1Q0W; MIU, 2FIF; DUIM, 2D3G; Vps9 CUE, 1P3Q; Cue2-CUE, 1OTR; UBA, 1WR1; GAT, 1YD8. Vps9 CUE domain forms a domain-swapped dimer, shown in blue and light blue. The missing part in Vps9 CUE was modelled on the basis of the apo structure.

UIM

The UIM is found in many trafficking proteins that recognize ubiquitinated cargo, the S5a subunit of the proteasome and other proteins [16–21]. Many UIMs have been shown to promote the ubiquitination of proteins that contain them [17–19,21–24]. UIMs bind to mono-ubiquitin with low affinity in the 100 μM to 2 mM range [25,26]. The UIM consists of a single α-helix, centred around a conserved alanine residue [26,27]. S5a and Vps27 contain two UIMs. The NMR structures of ubiquitin bound to the UIM-1 of Vps27 [27] and of the tandem UIMs of S5a [28,29] show that the UIM helix binds in a shallow hydrophobic groove on the surface of ubiquitin, and the alanine residue packs against Ile44 of ubiquitin. Other interactions are centred around Ile44 and bury a modest amount of surface area, consistent with the low affinity of the interaction. Vps27 UIM-1 and UIM-2 are connected by a highly mobile linker, and are randomly oriented with respect to each other [27]. They do not seem to co-operate in the binding of mono-ubiquitin.

UIM variants: MIU and DUIM

Two recently described UIM variants illustrate the versatility of single helix-based ubiquitin recognition. The MIU is a single helix that, so far, seems to be unique to one protein, the Rab5 exchange factor Rabex-5 [30,31]. The Rabex-5 MIU is attached to the helical C-terminus of the A20 ZnF (zinc finger) domain. The MIU is centred on a functionally essential alanine residue that contacts Ile44 of ubiquitin. The MIU helix sits in the same hydrophobic groove that binds the UIM, but does so in the opposite orientation. The N-terminus of the UIM has a position equivalent to the C-terminus of the MIU and vice versa. The MIU has more extensive contacts with ubiquitin than the UIM, and contains one additional turn of helix that is in contact with ubiquitin. Therefore, its affinity for ubiquitin is correspondingly higher, approx. 30 μM. Key hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions are preserved in the UIM and MIU, so the MIU appears to truly be an inverted functional cognate of the UIM. The MIU is a remarkably clear-cut and elegant example of convergent evolution.

The DUIM is another remarkable variation on the UIM theme. One face of the conventional UIM helix binds ubiquitin, whereas the other face is exposed to solvent. In the DUIM, two UIM sequences are interlaid on a single helix such that both faces are capable of binding to ubiquitin [32]. The individual binding events have comparable affinities with the conventional UIM [32]. The DUIM provides a mechanism for binding to two, rather than one, ubiquitin moiety, which provides an alternative to a double repeat of a conventional UIM. The human homologue of Vps27, Hrs, contains one DUIM, whereas yeast Vps27 contains two conventional UIMs. It is anticipated that DUIMs could bind to polyubiquitinated, multimono-ubiquitinated or oligomers of mono-ubiquitinated proteins with high co-operativity, although this has not been directly tested.

UBA

The UBA domain was the first ubiquitin-binding domain described. UBA domains were discovered as a region of homology in many proteins that were either involved in ubiquitination cascades or contained ubiquitin-like domains, or both [33]. UBA domains are compact three-helix bundles [34–36]. Polyubiquitin binding is the most established physiological function for the UBA domain [37–39]. UBA domains bind to mono-ubiquitin in vitro [40–42] and have been found to play a role in a variety of other protein–protein interactions [34,35,43]. The Ile44 patch on mono-ubiquitin binds to a conserved hydrophobic patch on the α1 and α3 helices of the UBA domain [44–50], similar to the equivalent region of the UBL (ubiquitin-like) domain of Dks2p [51]. There is some variation in the details of the orientation of the UBA domain relative to ubiquitin in different reports, but all of the structural studies agree on the identity of the binding sites on each partner. The only available crystal structure of a UBA–ubiquitin complex [51] and the NOE (nuclear Overhauser effect)-based NMR structures of UBA–mono-ubiquitin complexes [47,49] converge on a single orientation. This orientation agrees with predictions based on the structures of CUE domain–ubiquitin complexes [52,53].

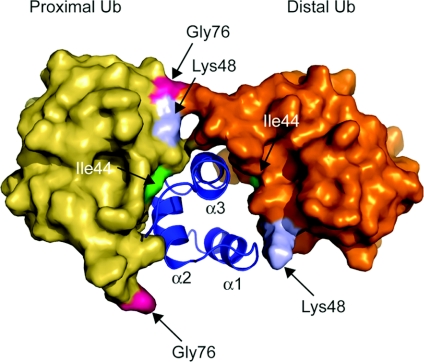

UBA domains and polyubiquitin recognition

The great majority of ubiquitin–ubiquitin-binding domain analyses have focused on interactions between ubiquitin monomers and domains. The late Cecile Pickart and her co-workers pioneered studies on UBA domain recognition of polyubiquitin chains formed through different types of linkage. In a study of 30 different UBA domains, four major specificity classes were identified [54]: class 1, which contains two known members, hHR23A UBA2 [54] and Mud1 UBA [55] domains, selectively binds to Lys48-linked polyubiquitin; class 2 binds preferentially to Lys63-linked polyubiquitin; class 3 UBA domains do not bind to ubiquitin at all; and class 4 UBA domains bind to polyubiquitin chains without any linkage specificity. Classes 1, 2 and 4 also bind to mono-ubiquitin, but in all cases with much lower affinity than to polyubiquitin. These classes must be considered provisional as they are not distinguished by any clear patterns of sequence conservation, and in most cases the mechanistic basis for discrimination is still unclear.

The mechanism of linkage-specific recognition is one of the most challenging questions for the ubiquitin-binding domain field. One major clue comes from studies of the conformations of different forms of polyubiquitin. Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin has a closed conformation [56], whereas, in contrast, Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin has an extended conformation [57]. Important inroads have been made from NMR studies of the hHR23A UBA2 and Mud1 UBA domains bound to Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin [48,55]. These structures reveal that the UBA domain binds in the centre of a ‘sandwich’ between the two mono-ubiquitin moieties (Figure 4). Both of the mono-ubiquitin moieties that bind to the hHR23A UBA2 domain interact with the UBA domain via their Ile44 patches, as seen in previous studies of mono-ubiquitin–UBA domain interactions [48]. The hHR23A UBA2 domain binds to the ‘distal’ mono-ubiquitin moiety through the same α1 and α3 helices that the UBA2 domain uses to bind free mono-ubiquitin [45]. For both the hHR23A and Mud1 UBA domains, the second mono-ubiquitin moiety binds to the rear of the domain formed by α2 and α3 helices. This is a novel interaction surface in the context of UBA domains. The rear binding is, however, reminiscent of the rear binding of one of the monomers in the Vps9–CUE dimer to a secondary recognition site on mono-ubiquitin [52]. The hHR23A UBA2 domain appears to interact directly with the Lys48 linkage [48], offering a partial explanation for linkage selectivity. However, the linkage-specific conformational alignment of the mono-ubiquitin moieties in a manner optimal for simultaneous front and rear binding is thought to be the dominant factor in Lys48 linkage-specific binding [48,55].

Figure 4. A model for polyubiquitin recognition by a UBA domain.

The UBA2 domain of hHR23A (blue) with two ubiquitin molecules (yellow and gold) covalently linked via an iso-peptide bond between Lys48 (light blue) of proximal ubiquitin and Gly76 (pink) of distal ubiquitin is shown. The proximal ubiquitin is placed in the same orientation as in Figure 1 for comparison. Ile44 (green) is also indicated. Each helix in the UBA2 domain is labelled. The protein data bank identication code used is 1ZO6.

CUE domain

The CUE domain was discovered through bioinformatics analysis of proteins related in various ways to protein degradation pathways [58]. Its function in ubiquitin binding was subsequently uncovered by screens for mono-ubiquitin interactors in yeast [59–61]. The C-terminal CUE domain of the yeast Rabex-5 homologue Vps9 binds mono-ubiquitin with high affinity. Like the UIM, CUE domains are capable of promoting the ubiquitination of proteins that contain them. CUE domains are structurally closely related to the UBA domains. Both are three-helix bundles and both bind ubiquitin via conserved hydrophobic residues at the C-terminus of the α1 helix [52,53].

Ubiquitin binding appears to be a universal property of CUE domains, as all the domains tested show binding. However, most CUE domains bind to mono-ubiquitin with much lower affinity than the Vps9 CUE domain [60]. The structures of the high-affinity Vps9 CUE domain and the low-affinity yeast Cue2 CUE domain complexes with ubiquitin explain how they bind mono-ubiquitin with such different affinities. The Vps9 CUE domain forms a domain-swapped dimer [52]. In domain swapping, a portion of one protomer, usually a free N- or C-terminus, changes places with the same region in another protomer, giving rise to dimers or higher-order oligomers. The domain-swapped Vps9 CUE dimer makes extended contacts with a large area on the surface of ubiquitin. The recognition includes the canonical Ile44 patch, but extends well beyond it to a region around Leu8 and Ile36. These interactions bury almost 900 Å2 of solvent accessible surface area, more than most other ubiquitin-binding domains. The affinity of the interaction has been estimated at between 1 and 20 μM, depending on the technique used [52,60]. In contrast, the Cue2 CUE domain is a monomer and binds mono-ubiquitin with a Kd of 155 μM [53]. The Cue2 CUE domain interacts only with the Ile44 patch on ubiquitin. The Cue2 CUE domain lacks the second interaction site found in the Vps9 CUE dimer, and therefore does not interact with the Leu8/Ile36 region of ubiquitin. The Vps9 CUE domain is thus able to bind ubiquitin with much higher affinity than other CUE domains, because it can form domain-swapped dimers and interact with a secondary site on ubiquitin.

GAT domain

Ubiquitin binding by the GAT domain was discovered as a result of the biological role of the GGA adaptor proteins in trafficking of ubiquitinated cargoes [62,63]. GAT domains are three-helix bundles [64–67] which serve as hubs for interacting with a range of trafficking proteins, including ubiquitin [62,68–71]. The GAT domains of both the GGA adaptor proteins and TOM1 bind to mono-ubiquitin with affinities of approx. 100 μM or weaker [70,72]. GAT domains appear to bind to the Ile44 patch on ubiquitin through two distinct sites [70]. The higher-affinity site appears to be the main locus for binding and is formed by helices α1 and α2, and structure of the mono-ubiquitin complex formed via this site with ubiquitin has been determined [72,73]. There is evidence from mutational analysis [69,70] and NMR chemical-shift perturbations [70] that support the existence of a second lower-affinity site on helices α2 and α3. This site is sterically blocked by crystal contacts in the published crystallographic analyses [72–74]. The two-site ubiquitin-binding mechanism of the GAT domain could facilitate binding to polyubiquitinated, multimono-ubiquinated or clustered mono-ubiquitinated proteins, as also proposed for the tandem- and double-UIM motifs and for the tandem-ubiquitin-binding domains of Rabex-5.

ZnF domains

ZnFs are the second largest class of ubiquitin-binding domains. Each of the three known ubiquitin-binding ZnFs were discovered initially through domain dissections of known ubiquitin-binding proteins. Ubiquitin binding by the NZF (Npl4 ZnF) domain was established in studies on Ufd1 Npl4 [75], a ubiquitin-binding adaptor protein of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. The A20 ZnF domain was found to function in the ubiquitin ligase step of the ubiquitin-chain editing activity of A20, a component of the NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) signalling cascade [76]. The UBP (ubiquitin-specific processing protease) ZnF domain was discovered via a dissection of the ubiquitin-binding sites of histone deactylases [77,78]. The ZnF ubiquitin-binding domains offer much more diversity in recognition and binding affinity than the helical domains (Figure 5). ZnF domains recognize three different regions on the surface of ubiquitin (Figure 1), and bind with affinities that are in the range of approx. 1 μM to nearly millimolar. Their structural diversity is mirrored by their wide range of biological roles.

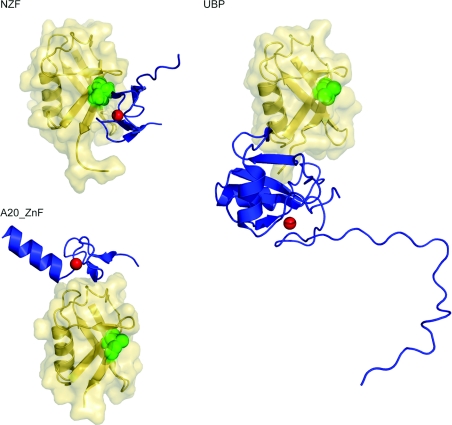

Figure 5. ZnF domain structures.

Three ZnF domains (NZF, UBP and A20 ZnF) are shown (blue) in ribbon representation, with ubiquitin (yellow) in ribbon and surface representations. Ile44, the centre of the hydrophobic recognition patch on the ubiquitin, is shown as green spheres. Ubiquitin molecules are placed in the same orientation as in Figure 1 for comparison. Zinc ions are depicted as red spheres. Protein data bank identication codes used are: A20 ZnF, 2FIF; NZF, 1Q5W; UBP, 2G45.

NZF domains

NZF domains are approx. 30-residue domains that are built around a single zinc-binding site [79,80]. Not all NZF domains bind to ubiquitin. Of those tested that do bind to ubiquitin, including Npl4, TAB2 (TAK1-binding protein 2) and the NZF2 of the ESCRT-II (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport II) subunit Vps36, affinities are 100 μM or weaker. A Thr–Phe pair in the first ‘zinc knuckle’ and a hydrophobic residue in the second knuckle (the TFΦ fingerprint) appear to be the main determinants for binding to ubiquitin. These residues make hydrophobic contacts with the ubiquitin Ile44 patch. The non-ubiquitin-binding subset of NZF domains, such as that of Ran-binding protein 2, do not possess the TFΦ fingerprint for ubiquitin recognition. However, engineered variants of the Ran-binding-protein-2 NZF domain that do have this fingerprint are capable of binding to ubiquitin with affinities comparable with those of naturally occurring ubiquitin-binding NZF domains [79].

A20 ZnF domains

A20 ZnF domains were first implicated in ubiquitin binding indirectly, by virtue of their role in the ubiquitin-chain editing activity of the A20 protein [76]. This remarkable multifunctional enzyme first removes a Lys63-linked polyubiquitin chain from its substrate, RIP (receptor-interacting protein), using an OTU (ovarian tumour) family de-ubiquitinating enzyme domain. It then attaches Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chains to RIP via its A20 ZnF domains. Rabex-5 is one of the mammalian homologues of yeast Vps9. Unlike Vps9, Rabex-5 does not contain a CUE domain, but instead binds ubiquitin via an N-terminal A20 ZnF domain fused to a MIU [81]. The Rabex-5 A20 ZnF domain binds ubiquitin with 12 to 22 μM affinity [30,31]. The A20 ZnF domains use a pair of aromatic residues and several polar residues to bind to a predominantly polar patch on ubiquitin centred on Asp58. The A20 ZnF-binding epitope on ubiquitin does not overlap with the Ile44 patch.

ZnF UBP

The ZnF UBP is a ubiquitin-binding module found in various de-ubiquitinating enzymes, the ubiquitin ligase IMP/BRAP2 and the microtubule deacetylase HDAC6. The ZnF UBP has also been referred to as the PAZ (polyubiquitin-associated zinc binding) domain, although it is unrelated to the widely studied RNA-binding PAZ domain. The ZnF UBP domain is approx. 130 residues in length, much larger than other ubiquitin-binding ZnFs. The domain is built around a single zinc-binding site in its N-terminal half which is fused to an α/β fold [82]. The ZnF UBP is one of the highest affinity ubiquitin binders among known binding domains: Kd=3 μM for the human isopeptidase T ZnF UBP [82]. The free C-terminal glycine residue of ubiquitin is required for ZnF UBP binding. The structure of the isopeptidase T ZnF UBP domain–ubiquitin complex shows that the extended C-terminus of ubiquitin penetrates deep into a tunnel-like cavity in the ZnF UBP domain. The free C-terminal carboxylate of ubiquitin makes multiple hydrogen bonds at the bottom of the cavity. The extensive interactions with the C-terminus of ubiquitin are supplemented by interactions with the Ile36 surface region, but there are no interactions with the Ile44 patch.

UBZ (ubiquitin-binding ZnF) domain

The UBZ domain occurs in Y-family DNA polymerases [83]. The UBZ domain consists of approx. 30 amino acid residues, and is presumed to bind to a single zinc ion based on its four conserved cysteine and histidine residues.

Ubc (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme)-related domains

Ubcs, also known as E2, are intermediates between the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) and the ubiquitin ligase (E3) in protein ubiquitination [2]. Ubcs all contain a common 150-amino-acid catalytic core with an α/β fold [2] (Figure 6). A conserved active-site cysteine residue forms a thiolester bond with the ubiquitin C-terminus as part of the reaction cycle [2]. Under normal catalytic conditions, the thiolester-linked ubiquitin moiety that is transferred is thought to have sparse non-covalent interactions with the Ubc [2]. Ubc enzymology is described elsewhere [2]. However, the Ubc fold binds ubiquitin non-covalently in two circumstances described below.

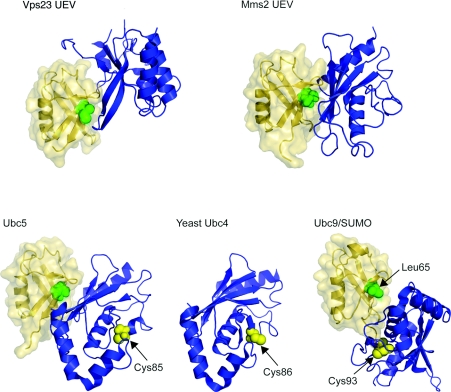

Figure 6. Ubc-related domain structures.

Upper panel: UEV domains of Vps23 and Mms2 are shown (blue) in ribbon representation with ubiquitin (yellow) in ribbon and surface representations. Ile44, the centre of the hydrophobic recognition patch on the ubiquitin, is shown as green spheres. Ubiquitin molecules are placed in the same orientation as in Figure 1 for comparison. Protein data bank identication codes used are: Vps23 UEV, 1UZX; Mms2 UEV, 1ZGU. Lower panels: Ubc5 (blue) is shown on the left with ubiquitin (yellow). The catalytically important Cys85 is depicted as yellow sphere. Yeast Ubc4 is presented in the middle panel for comparison. Again, catalytic Cys86 is shown as yellow sphere. On the right, Ubc9 (blue) complexed with SUMO (small ubiquitin-related modifier) (yellow) is shown [109], as there is no equivalent structure of a Ubc–ubiquitin conjugate available. Leu65 on SUMO, equivalent to Ile44 from sequence alignment, is indicated as green sphere and Cys93 of Ubc9 as yellow sphere. Protein data bank identication codes used are: Ubc5, 2FUH; Ubc4, 1QCQ; Ubc9/SUMO, 1Z5S. The SUMO molecule is also placed in the same orientation as the ubiqutin molecule.

UEV (Ubc E2 variant) domain

The UEV domain is a Ubc fold lacking a catalytic cysteine residue. Mms2 is a UEV domain protein that heterodimerizes with Ubc13 to facilitate the assembly of polyubiquitin chains. Ubiquitin binds the UEV domain of Mms2 with 100 μM affinity [84], and the interaction surface has been inferred from NMR chemical-shift perturbation studies [85,86]. The ESCRT-I trafficking complex binds to the mono-ubiquitin moieties of transmembrane cargo proteins through the UEV domain of its Vps23 subunit. The affinity of the UEV domain for mono-ubiquitin is approx. 500 μM [87], which is at the low end of the spectrum for known ubiquitin-binding domains. The structures of the UEV domains of yeast Vps23 [88] and its human homologue Tsg101 [89] have been determined in complex with ubiquitin. In both structures, two different regions of the UEV domains contact ubiquitin. The β1–β2 ‘tongue’ contacts the Ile44 hydrophobic patch of ubiquitin, the same region involved in contacts with the Vps27 UIM and with other mono-ubiquitin-binding domains. The loop between the α3 and α3′ helices forms a ‘lip’ that contacts a hydrophilic site centred on Gln62 of ubiquitin [88,89]. In contrast with the Ile44 site, the Gln62 site does not participate in most other known ubiquitin–ubiquitin-binding domain interactions.

Non-covalent ubiquitin binding by Ubc catalytic domains

Many Ubcs participate in the progressive formation of polyubiquitin chains. Chain elongation requires non-covalent interactions with the nascent chain facilitated by the catalytic machinery of ubiquitination. Many Ubcs contain ubiquitin-binding domains fused to the Ubc catalytic domain. Class I Ubcs, however, contain only a Ubc catalytic domain. UbcH5C, a class I Ubc, binds non-covalently to ubiquitin with an affinity of approx. 300 μM [90]. UbcH5C binds to the Ile44 patch of ubiquitin via its β-sheet [90]. This surface is on the opposite side of the enzyme from the catalytic site, and is distinct from the ubiquitin-binding site on the UEV domain.

Other ubiquitin-binding domains

UBM (ubiquitin-binding motif)

The UBM was discovered in a screen for domains interacting with ubiquitin independent of Ile44 [83]. UBMs, like the UBZ domains, are found in Y-family DNA polymerases involved in DNA repair [83]. UBMs bind to mono-ubiquitin with an affinity of approx. 180 μM. The UBM contains approx. 30 residues, is predicted to be mostly helical, and is centred on an invariant Leu–Pro pair. The UBM epitope on ubiquitin is centred around Leu8, near, but not overlapping with, Ile44 [83].

GLUE: a ubiquitin-binding PH (pleckstrin homology) domain

The Vps36 subunit of the ESCRT-II trafficking complex binds both phosphoinositides and ubiquitin, which are molecules central to its function in sorting ubiquitinated transmembrane proteins at endosomal membranes. Human Vps36 (also known as EAP45 (ELL-associated protein 45) binds to both ubiquitin and phosphoinositides via its N-terminal GLUE (GRAM-like ubiquitin binding in EAP45) domain [91]. Yeast Vps36 contains a split GLUE domain into which two NZF domains are inserted. In the case of yeast Vps36, ubiquitin does not bind to the core GLUE domain [92], but rather to the second of the inserted NZF domains [79]. The GLUE domain structure shows that it is an example of a PH domain. Many PH domains bind phosphoinositides, but there are not other reports of their binding to ubiquitin.

Jab1/MPN domain

Jab1/MPN domains were first characterized as the catalytic domain of metalloproteases specific for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like protein isopeptide bonds [93–95]. Catalytically active Jab1/MPN domains contain a metalloprotease signature motif known as a JAMM (Jab1/MPN domain metalloenzyme). Variants of the Jab1/MPN domains lack key residues in this motif, by analogy to UEV domain, an inactive Ubc variant. The Jab1/MPN domain of the pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp8p binds to ubiquitin with an affinity of approx. 380 μM [96]. The binding is thought to involve the Ile44 patch on the basis of mutational studies of binding affinity, and appears to be important for the biological function of Prp8p [96].

PFU (PLAA family ubiquitin binding) domain

The PFU domain of Doa1 was recently shown to bind both mono- and poly-ubiquitin [97]. The PFU domain does not have significant sequence identity to other ubiquitin-binding domains, but there may be structural homology with the UEV domain on the basis of its predicted secondary structure [97].

UBIQUITIN-BINDING DOMAINS: THEMES AND MECHANISMS

Structure and affinity of ubiquitin-binding domains

The only consistent theme in the structures and affinities of ubiquitin-binding domains seems to be their diversity. A wide range of structural folds are capable of binding ubiquitin. Contrary with early impressions, ubiquitin-binding domains recognize various surfaces on ubiquitin, not just the patch surrounding Ile44. The only generalization that can still be made is that known ubiquitin-binding domains are compact and have some regular secondary structure or a ZnF, or both, as core elements. So far there have been no confirmed reports of short unstructured peptide motifs acting as ubiquitin-binding domains.

The early impression that all ubiquitin-binding domains have very low affinity for mono-ubiquitin also now appears to have been too broad a generalization. We now know that the affinity of ubiquitin-binding domains for mono-ubiquitin can be as high as Kd=∼1 μM. As a crude generalization, binding domains in enzymes with activities involved in or regulated by ubiquitination tend to have affinities in the low micromolar range. Adaptors that bind ubiquitinated membrane proteins contain domains that typically bind mono-ubiquitin with affinities in the 100 μM range or lower. The largest class of characterized ubiquitin-binding domains do have mono-ubiquitin affinities which seem surprisingly low for a physiological interaction.

Oligomerization, polymerization and membrane binding in ubiquitin recognition

Mono-ubiquitination is a physiological regulatory mechanism [98], yet most ubiquitin-binding domains have a very low affinity for mono-ubiquitin. There are several ways to resolve this apparent contradiction. Multiple mono-ubiquitin moieties may be presented by covalent ubiquitination at multiple sites on a single protein, known as multimono-ubiquitination [99,100]. The best known multimono-ubiquitinated protein, EGFR (epidermal-growth-factor receptor), is also polyubiquitinated, primarily with Lys63-linked chains [101]. Both multimono-ubiquitination and polyubiquitination present multiple mono-ubiquitin moieties. The oligomerization of singly mono-ubiquitinated proteins might offer another mechanism for presenting multiple ubiquitin moieties that can function in addition to polyubiquitination [102,103] (Figure 7). Multiple mono-ubiquitin moieties can be recognized with high avidity by multiple ubiquitin-binding domains, by multiple surfaces of a ubiquitin-binding domain or by a combination of the two. The tandem UIMs in Vps27 and epsin, and the tandem A20 ZnF and MIU of Rabex-5, are examples of multiple ubiquitin-binding domains within a protein. The combined A20 ZnF and MIU of Rabex-5 bind to immobilized ubiquitin on a sensor chip, a possible facsimile of oligomeric ubiquitin on a membrane, with Kd=1 μM, even though the individual domains have affinities in the 12–29 μM range [30]. In other instances, ubiquitin-binding domains such as GAT and DUIM bind two mono-ubiquitin moieties simultaneously, providing a different mechanism for avidity [32,104].

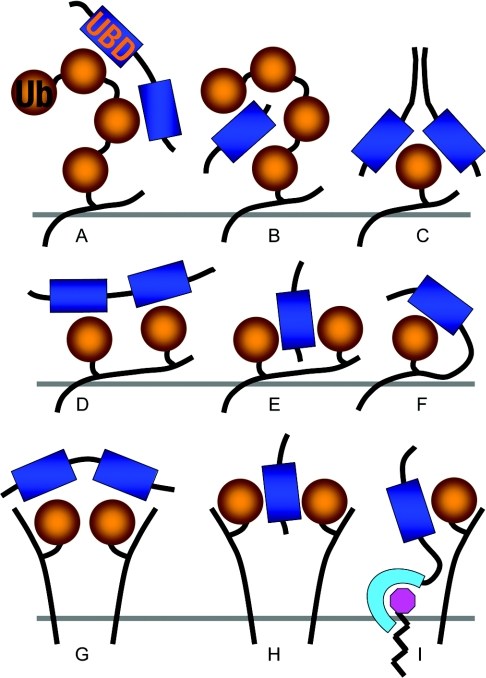

Figure 7. Co-operativity between weak mono-ubiquitin–ubiquitin-binding domain interactions.

(A) Recognition of polyubiquitin by tandem mono-ubiquitin-binding domains (UBD) [102,103]. (B) Recognition of polyubiquitin by a two different faces of ubiquitin-binding domain [48,55]. (C) High-affinity binding to mono-ubiquitin by a dimeric ubiquitin-binding domain that uses two different faces on each of the two monomers to recognize two different sites on a single ubiquitin moiety [52]. (D) Recognition of a multimono-ubiquitinated protein by tandem mono-ubiquitin-binding domains [100,110]. (E) Recognition of a multimono-ubiquitinated protein by a two-faced ubiquitin-binding domain [32]. (F) The local concentration facilitates intramolecular inhibition by auto-ubiquitination via a univalent ubiquitin–ubiquitin-binding domain interaction [107]. (G) Recognition of clustered mono-ubiquitinated membrane proteins by tandem mono-ubiquitin-binding domains. (H) Recognition of clustered mono-ubiquitinated membrane proteins by a two-faced ubiquitin-binding domain. (I) Co-operative recognition of a mono-ubiquitinated membrane proteins by a protein containing lipid and mono-ubiquitin-binding domains.

These avidity effects may be further strengthened as many mono-ubiquitin-binding proteins and complexes come together to form assemblies on membranes. Such processes are typically initiated by high-affinity interactions with phosphoinositides (i.e. between FYVE domains and phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate [105]) or small G-proteins {i.e. between GGAs and Arf1 (ADP-ribosylation-factor-binding protein 1) [106]}, which localize ubiquitin-binding proteins to cell membranes. This increases the local concentration of ubiquitin-binding proteins at the membrane, and provides yet one more mechanism for binding to mono-ubiquitinated membrane proteins with a high affinity. This is best illustrated by the ESCRT system for sorting mono-ubiquitinated proteins into multivesicular bodies [105].

Auto-ubiquitination of ubiquitin-binding domain proteins

Auto-ubiquitination refers to the covalent ubiquitination of a ubiquitin receptor. A number of proteins that contain UIM [17–19,21–24], CUE [59–61], MIU [31,81] and A20 ZnF [30,81] domains are auto-ubiquitinated in a process that requires a competent ubiquitin-binding domain. The mechanism of ubiquitin-binding domain-dependent auto-ubiquitination, known as coupled ubiquitination, remains elusive. The A20 ZnF of Rabex-5 has a ubiquitin ligase activity that depends on its ability to bind to the ubiquitin moiety in a covalent ubiquitin–Ubc adduct. The A20 ZnF domain recruits some ubiquitin-bound Ubcs (i.e. UbcH5C), but not others (i.e. Ube2g2). Since there is some apparent Ubc specificity, it is likely that the A20 ZnF has a direct physical interaction with the Ubc catalytic domain. Recent findings suggest that UIMs are capable of acting as ubiquitin ligases ‘in cis’ to auto-ubiquitinate the proteins that contain them (Ivan Dikic, personal communication). The ligase mechanism involves direct recruitment of a thiolester-linked ubiquitin–Ubc conjugate in the same manner as the A20 ZnF domain.

The biological function of auto-ubiquitination is currently under investigation. One popular idea is that there could be an intramolecular interaction between a ubiquitin-binding domain and a ubiquitin moiety covalently attached to some other region of the same protein (i.e. not within to the ubiquitin-binding domain). This would sequester the ubiquitin-binding domain in an intramolecular interaction and thus render it non-functional for intermolecular binding (Figure 8). The mono-ubiquitination of the endocytic proteins Sts1, Sts2, Eps15 and Hrs blocks binding of these proteins to the ubiquitinated target proteins by intramolecular interactions by this mechanism [107]. It will be important to determine if auto-ubiquitination can have other regulatory consequences beyond the intramolecular sequestration of ubiquitin-binding domains, such as, perhaps, regulation of the guanine nucleotide-exchange factor activity of the auto-ubiquitinated proteins Vps9 and Rabex-5. Another interesting possibility, although not strictly related to auto-ubiquitination, is the possibility of protein kinase regulation through engagement of a UBA domain [108].

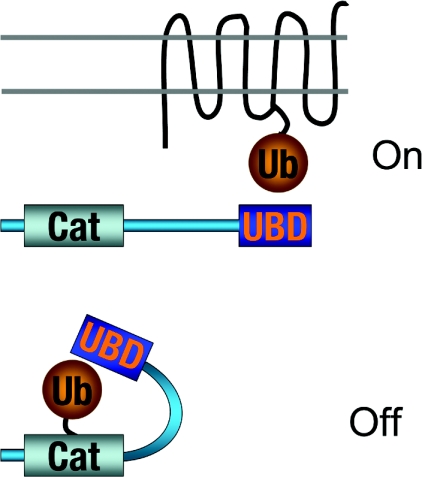

Figure 8. Auto-inhibition of ubiquitin-binding domain proteins.

A present model for the regulation of ubiquitin-binding-domain-containing proteins by ubiquitination. UBD, ubiquitin-binding domain.

CONCLUSION

It has been a decade since the first ubiquitin-binding domain, the UBA domain, was identified. The field has matured rapidly in the past 5 years. At least 15 more ubiquitin-binding domains have been identified in the past 5 years. Many of the main principles of ubiquitin recognition by this class of domains have been worked out. The physiological roles of these domains have expanded far beyond the first discoveries in proteasomal targeting. The linkage-specific recognition of polyubiquitin chains, and the related question of discrimination between polyubiqutin, ‘multimono-ubiquitin’ and mono-ubiquitin remain major issues for the field. Ubiquitin-binding domains have largely been studied in isolation. A second, and even more important, frontier for the field will be to integrate the large body of information and experimentation on isolated domains into an understanding of the intact proteins and multiprotein assemblies that contain these domains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juan Bonifacino, Allan Weissman, Craig Blackstone and Yihong Ye for constructive comments on the manuscript, and many colleagues in the ubiquitin field and the members of the J.H.H.'s laboratory for discussions. Research in the J.H.H.'s laboratory is supported by the intramural research program of the NIDDK (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), NIH (National Institutes of Health), and by the IATAP (Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program), NIH.

References

- 1.Hershko A., Ciechanover A., Varshavsky A. The ubiquitin system. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/80384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickart C. M. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weissman A. M. Themes and variations on ubiquitylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35056563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstrasser M. Evolution and function of ubiquitin-like protein-conjugation systems. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:E153–E157. doi: 10.1038/35019643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller J., Gordon C. The regulation of proteasome degradation by multi-ubiquitin chain binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3224–3230. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsasser S., Finley D. Delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to protein-unfolding machines. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005;7:742–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicke L. A new ticket for entry into budding vesicles – ubiquitin. Cell. 2001;106:527–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raiborg C., Rusten T. E., Stenmark H. Protein sorting into multivesicular endosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:446–455. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staub O., Rotin D. Role of ubiquitylation in cellular membrane transport. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:669–707. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang T. T., D'Andrea A. D. Regulation of DNA repair by ubiquitylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:323–334. doi: 10.1038/nrm1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Fiore P. P., Polo S., Hofmann K. When ubiquitin meets ubiquitin receptors: a signalling connection. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nrm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haglund K., Dikic I. Ubiquitylation and cell signaling. EMBO J. 2005;24:3353–3359. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicke L., Schubert H. L., Hill C. P. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper J. W., Schulman B. A. Structural complexity in ubiquitin recognition. Cell. 2006;124:1133–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizuno E., Kawahata K., Kato M., Kitamura N., Komada M. STAM proteins bind ubiquitinated proteins on the early endosome via the VHS domain and ubiquitin-interacting motif. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:3675–3689. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann K., Falquet L. A ubiquitin-interacting motif conserved in components of the proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation systems. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polo S., Sigismund S., Faretta M., Guidi M., Capua M. R., Bossi G., Chen H., De Camilli P., Di Fiore P. P. A single motif responsible for ubiquitin recognition and monoubiquitination in endocytic proteins. Nature. 2002;416:451–455. doi: 10.1038/416451a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih S. C., Katzmann D. J., Schnell J. D., Sutanto M., Emr S. D., Hicke L. Epsins and Vps27p/Hrs contain ubiquitin-binding domains that function in receptor endocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:389–393. doi: 10.1038/ncb790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilodeau P. S., Urbanowski J. L., Winistorfer S. C., Piper R. C. The Vps27p–Hse1p complex binds ubiquitin and mediates endosomal protein sorting. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:534–539. doi: 10.1038/ncb815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raiborg C., Bache K. G., Gillooly D. J., Madshush I. H., Stang E., Stenmark H. Hrs sorts ubiquitinated proteins into clathrin-coated microdomains of early endosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:394–398. doi: 10.1038/ncb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klapisz E., Sorokina I., Lemeer S., Pijnenburg M., Verkleij A. J., Henegouwen P. A ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) is essential for Eps15 and Eps15R ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30746–30753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oldham C. E., Mohney R. P., Miller S. L. H., Hanes R. N., O'Bryan J. P. The ubiquitin-interacting motifs target the endocytic adaptor protein epsin for ubiquitination. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00900-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz M., Shtiegman K., Tal-Or P., Yakir L., Mosesson Y., Harari D., Machluf Y., Asao H., Jovin T., Sugamura K., Yarden Y. Ligand-independent degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor involves receptor ubiquitylation and hgs, an adaptor whose ubiquitin-interacting motif targets ubiquitylation by Nedd4. Traffic. 2002;3:740–751. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller S. L. H., Malotky E., O'Bryan J. P. Analysis of the role of ubiquitin-interacting motifs in ubiquitin binding and ubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33528–33537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shekhtman A., Cowburn D. A ubiquitin-interacting motif from Hrs binds to and occludes the ubiquitin surface necessary for polyubiquitination in monoubiquitinated proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;296:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher R. D., Wang B., Alam S. L., Higginson D. S., Robinson H., Sundquist W. I., Hill C. P. Structure and ubiquitin binding of the ubiquitin-interacting motif. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:28976–28984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson K. A., Kang R. S., Stamenova S. D., Hicke L., Radhakrishnan I. Solution structure of Vps27 UIM-ubiquitin complex important for endosomal sorting and receptor downregulation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4597–4606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryu K. S., Lee K. J., Bae S. H., Kim B. K., Kim K. A., Choi B. S. Binding surface mapping of intra- and interdomain interactions among hHR23B, ubiquitin, and polyubiquitin binding site 2 of S5a. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36621–36627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q. H., Young P., Walters K. J. Structure of S5a bound to monoubiquitin provides a model for polyubiquitin recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S., Tsai Y. C., Mattera R., Smith W. J., Kostelansky M. S., Weissman A. M., Bonifacino J. S., Hurley J. H. Structural basis for ubiquitin recognition and autoubiquitination by Rabex-5. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:264–271. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Penengo L., Mapelli M., Murachelli A. G., Confalonieri S., Magri L., Musacchio A., Di Fiore P. P., Polo S., Schneider T. R. Crystal structure of the ubiquitin binding domains of rabex-5 reveals two modes of interaction with ubiquitin. Cell. 2006;124:1183–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirano S., Kawasaki M., Ura H., Kato R., Raiborg C., Stenmark H., Wakatsuki S. Double-sided ubiquitin binding of Hrs-UIM in endosomal protein sorting. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:272–277. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann K., Bucher P. The UBA domain: a sequence motif present in multiple enzyme classes of the ubiquitination pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:172–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dieckmann T., Withers-Ward E. S., Jarosinski M. A., Liu C. F., Chen I. S. Y., Feigon J. Structure of a human DNA repair protein UBA domain that interacts with HIV-1 Vpr. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:1042–1047. doi: 10.1038/4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Withers-Ward E. S., Mueller T. D., Chen I. S. Y., Feigon J. Biochemical and structural analysis of the interaction between the UBA(2) domain of the DNA repair protein HHR23A and HIV-1 Vpr. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14103–14112. doi: 10.1021/bi0017071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mueller T. D., Feigon J. Solution structures of UBA domains reveal a conserved hydrophobic surface for protein–protein interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1243–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkinson C. R. M., Seeger M., Hartmann-Petersen R., Stone M., Wallace M., Semple C., Gordon C. Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:939–943. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funakoshi M., Sasaki T., Nishimoto T., Kobayashi H. Budding yeast Dsk2p is a polyubiquitin-binding protein that can interact with the proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:745–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012585199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raasi S., Pickart C. M. Rad23 ubiquitin-associated domains (UBA) inhibit 26 S proteasome-catalyzed proteolysis by sequestering lysine 48-linked polyubiquitin chains. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8951–8959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m212841200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vadlamudi R. K., Joung I., Strominger J. L., Shin J. p62, a phosphotyrosine-independent ligand of the SH2 domain of p56lck, belongs to a new class of ubiquitin-binding protiens. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20235–20237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertolaet B. L., Clarke D. J., Wolff M., Watson M. H., Henze M., Divita G., Reed S. I. UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:417–422. doi: 10.1038/87575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen L., Shinde U., Ortolan T. G., Madura K. Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains in Rad23 bind ubiquitin and promote inhibition of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:933–938. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bertolaet B. L., Clarke D. J., Wolff M., Watson M. H., Henze M., Divita G., Reed S. I. UBA domains mediate protein–protein interactions between two DNA damage-inducible proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:955–963. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Q. H., Goh A. M., Howley P. M., Walters K. J. Ubiquitin recognition by the DNA repair protein hHR23a. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13529–13535. doi: 10.1021/bi035391j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller T. D., Kamionka M., Feigon J. Specificity of the interaction between ubiquitin-associated domains and ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:11926–11936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan X. M., Simpson P., McKeown C., Kondo H., Uchiyama K., Wallis R., Dreveny I., Keetch C., Zhang X. D., Robinson C., et al. Structure, dynamics and interactions of p47, a major adaptor of the AAA ATPase, p97. EMBO J. 2004;23:1463–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohno A., Jee J., Fujiwara K., Tenno T., Goda N., Tochio H., Kobayashi H., Hiroaki H., Shirakawa M. Structure of the UBA domain of Dsk2p in complex with ubiquitin: molecular determinants for ubiquitin recognition. Structure. 2005;13:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varadan R., Assfalg M., Raasi S., Pickart C., Fushman D. Structural determinants for selective recognition of a lys48-linked polyubiquitin chain by a UBA domain. Mol. Cell. 2005;18:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swanson K. A., Hicke L., Radhakrishnan I. Structural basis for monoubiquitin recognition by the Ede1 UBA domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;358:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang Y. G., Song A. X., Gao Y. G., Shi Y. H., Lin X. J., Cao X. T., Lin D. H., Hu H. Y. Solution structure of the ubiquitin-associated domain of human BMSC-UbP and its complex with ubiquitin. Prot. Sci. 2006;15:1248–1259. doi: 10.1110/ps.051995006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lowe E. D., Hasan N., Trempe J. F., Fonso L., Noble M. E. M., Endicott J. A., Johnson L. N., Brown N. R. Structures of the Dsk2 UBL and UBA domains and their complex. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:177–188. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905037777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prag G., Misra S., Jones E. A., Ghirlando R., Davies B. A., Horazdovsky B. F., Hurley J. H. Mechanism of ubiquitin recognition by the CUE domain of Vps9p. Cell. 2003;113:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kang R. S., Daniels C. M., Francis S. A., Shih S. C., Salerno W. J., Hicke L., Radhakrishnan I. Solution structure of a CUE–ubiquitin complex reveals a conserved mode of ubiquitin binding. Cell. 2003;113:621–630. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raasi S., Varadan R., Fushman D., Pickart C. M. Diverse polyubiquitin interaction properties of ubiquitin-associated domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:708–714. doi: 10.1038/nsmb962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trempe J. F., Brown N. R., Lowe E. D., Gordon C., Campbell I. D., Noble M. E. M., Endicott J. A. Mechanism of Lys48-linked polyubiquitin chain recognition by the Mud1 UBA domain. EMBO J. 2005;24:3178–3189. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varadan R., Walker O., Pickart C., Fushman D. Structural properties of polyubiquitin chains in solution. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;324:637–647. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Varadan R., Assfalg N., Haririnia A., Raasi S., Pickart C., Fushman D. Solution conformation of Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin chain provides clues to functional diversity of polyubiquitin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:7055–7063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ponting C. P. Proteins of the endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation pathway: domain detection and function prediction. Biochem. J. 2000;351:527–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Donaldson K. M., Yin H. W., Gekakis N., Supek F., Joazeiro C. A. P. Ubiquitin signals protein trafficking via interaction with a novel ubiquitin binding domain in the membrane fusion regulator, Vps9p. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:258–262. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shih S. C., Prag G., Francis S. A., Sutanto M. A., Hurley J. H., Hicke L. A ubiquitin-binding motif required for intramolecular monoubiquitylation, the CUE domain. EMBO J. 2003;22:1273–1281. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies B. A., Topp J. D., Sfeir A. J., Katzmann D. J., Carney D. S., Tall G. G., Friedberg A. S., Deng L., Chen Z. J., Horazdovsky B. F. Vps9p CUE domain ubiquitin binding is required for efficient endocytic protein traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19826–19833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puertollano R., Bonifacino J. S. Interactions of GGA3 with the ubiquitin sorting machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:244–251. doi: 10.1038/ncb1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott P. M., Bilodeau P. S., Zhdankina O., Winistorfer S. C., Hauglund M. J., Allaman M. M., Kearney W. R., Robertson A. D., Boman A. L., Piper R. C. GGA proteins bind ubiquitin to facilitate sorting at the trans-Golgi network. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:252–259. doi: 10.1038/ncb1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins B. M., Watson P. J., Owen D. J. The structure of the GGA1-GAT domain reveals the molecular basis for ARF binding and membrane association of GGAs. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suer S., Misra S., Saidi L. F., Hurley J. H. Structure of the GAT domain of human GGA1: a syntaxin amino-terminal domain fold in an endosomal trafficking adaptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4451–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0831133100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu G. Y., Zhai P., He X. Y., Terzyan S., Zhang R. G., Joachimiak A., Tang J., Zhang X. J. C. Crystal structure of the human GGA1 GAT domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6392–6399. doi: 10.1021/bi034334n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shiba T., Kawasaki M., Takatsu H., Nogi T., Matsugaki N., Igarashi N., Suzuki M., Kato R., Nakayama K., Wakatsuki S. Molecular mechanism of membrane recruitment of GGA by ARF in lysosomal protein transport. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:386–393. doi: 10.1038/nsb920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shiba Y., Katoh Y., Shiba T., Wakatsuki S., Nakayama K. GAT (GGA and Tom1) domain responsible for ubiquitin binding and ubiquitination. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:314A–314A. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mattera R., Puertollano R., Smith W. J., Bonifacino J. S. The trihelical bundle subdomain of the GGA proteins interacts with multiple partners through overlapping but distinct sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31409–31418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bilodeau P. S., Winistorfer S. C., Allaman M. M., Surendhran K., Kearney W. R., Robertson A. D., Piper R. C. The GAT domains of clathrin-associated GGA proteins have two ubiquitin binding motifs. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:54808–54816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406654200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katoh Y., Shiba Y., Mitsuhashi H., Yanagida Y., Takatsu H., Nakayama K. Tollip and Tom1 form a complex and recruit ubiquitin-conjugated proteins onto early endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:24435–24443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prag G., Lee S. H., Mattera R., Arighi C. N., Beach B. M., Bonifacino J. S., Hurley J. H. Structural mechanism for ubiquitinated-cargo recognition by the Golgi-localized, gamma-ear-containing, ADP-ribosylation-factor-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:2334–2339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500118102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kawasaki M., Shiba T., Shiba Y., Yamaguchi Y., Matsugaki N., Igarashi N., Suzuki M., Kato R., Kato K., Nakayama K., Wakatsuki S. Molecular mechanism of ubiquitin recognition by GGA3 GAT domain. Genes Cells. 2005;10:639–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akutsu M., Kawasaki M., Katoh Y., Shiba T., Yamaguchi Y., Kato R., Kato K., Nakayama K., Wakatsuki S. Structural basis for recognition of ubiquitinated cargo by Tom1-GAT domain. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5385–5391. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer H. H., Wang Y. Z., Warren G. Direct binding of ubiquitin conjugates by the mammalian p97 adaptor complexes, p47 and Ufd1-Npl4. EMBO J. 2002;21:5645–5652. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wertz I. E., O'Rourke K. M., Zhou H. L., Eby M., Aravind L., Seshagiri S., Wu P., Wiesmann C., Baker R., Boone D. L., et al. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappa B signalling. Nature. 2004;430:694–699. doi: 10.1038/nature02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hook S. S., Orian A., Cowley S. M., Eisenman R. N. Histone deacetylase 6 binds polyubiquitin through its zinc finger (PAZ domain) and copurifies with deubiquitinating enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:13425–13430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seigneurin-Berny D., Verdel A., Curtet S., Lemercier C., Garin J., Rousseaux S., Khochbin S. Identification of components of the murine histone deacetylase 6 complex: Link between acetylation and ubiquitination signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:8035–8044. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8035-8044.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alam S. L., Sun J., Payne M., Welch B. D., Black B. K., Davis D. R., Meyer H. H., Emr S. D., Sundquist W. I. Ubiquitin interactions of NZF zinc fingers. EMBO J. 2004;23:1411–1421. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang B., Alam S. L., Meyer H. H., Payne M., Stemmler T. L., Davis D. R., Sundquist W. I. Structure and ubiquitin interactions of the conserved zinc finger domain of Npl4. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:20225–20234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300459200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mattera R., Tsai Y. C., Weissman A. M., Bonifacino J. S. The Rab5 guanine nucleotide exchange factor Rabex-5 binds ubiquitin (Ub) and functions as a Ub ligase through an atypical Ub-interacting motif and a zinc finger domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6874–6883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reyes-Turcu F. E., Horton J. R., Mullally J. E., Heroux A., Cheng X. D., Wilkinson K. D. The ubiquitin binding domain ZnFUBP recognizes the C-terminal diglycine motif of unanchored ubiquitin. Cell. 2006;124:1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bienko M., Green C. M., Crosetto N., Rudolf F., Zapart G., Coull B., Kannouche P., Wider G., Peter M., Lehmann A. R., Hofmann K., Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding domains in Y-family polymerases regulate translesion synthesis. Science. 2005;310:1821–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.1120615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McKenna S., Hu J., Moraes T., Xiao W., Ellison M. J., Spyracopoulos L. Energetics and specificity of interactions within Ub·Uev·Ubc13 human ubiquitin conjugation complexes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7922–7930. doi: 10.1021/bi034480t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McKenna S., Spyracopoulos L., Moraes T., Pastushok L., Ptak C., Xiao W., Ellison M. J. Noncovalent interaction between ubiquitin and the human DNA repair protein mms2 is required for ubc13-mediated polyubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40120–40126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McKenna S., Moraes T., Pastushok L., Ptak C., Xiao W., Spyracopoulos L., Ellison M. J. An NMR-based model of the ubiquitin-bound human ubiquitin conjugation complex Mms2·Ubc13 – the structural basis for lysine 63 chain catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:13151–13158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garrus J. E., von Schwedler U. K., Pornillos O. W., Morham S. G., Zavitz K. H., Wang H. E., Wettstein D. A., Stray K. M., Cote M., Rich R. L., et al. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell. 2001;107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Teo H., Veprintsev D. B., Williams R. L. Structural insights into endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT-I) recognition of ubiquitinated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28689–28696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sundquist W. I., Schubert H. L., Kelly B. N., Hill G. C., Holton J. M., Hill C. P. Ubiquitin recognition by the human TSG101 protein. Mol. Cell. 2004;13:783–789. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brzovic P. S., Lissounov A., Christensen D. E., Hoyt D. W., Klevit R. E. A UbcH5/ubiquitin noncovalent complex is required for processive BRCA1-directed ubiquitination. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:873–880. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Slagsvold T., Aasland R., Hirano S., Bache K. G., Raiborg C., Trambaiano D., Wakatsuki S., Stenmark H. Eap45 in mammalian ESCRT-II binds ubiquitin via a phosphoinositide-interacting GLUE domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19600–19606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Teo H., Gill D. J., Sun J., Perisic O., Veprintsev D. B., Vallis Y., Emr S. D., Williams R. L. ESCRT-I core and ESCRT-II GLUE domain structure reveal role for GLUE in linking to ESCRT-I and membranes. Cell. 2006;125:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cope G. A., Suh G. S. B., Aravind L., Schwarz S. E., Zipursky S. L., Koonin E. V., Deshaies R. J. Role of predicted metalloprotease motif of Jab1/Csn5 in cleavage of Nedd8 from Cul1. Science. 2002;298:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1075901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Verma R., Aravind L., Oania R., McDonald W. H., Yates J. R., Koonin E. V., Deshaies R. J. Role of Rpn11 metalloprotease in deubiquitination and degradation by the 26 S proteasome. Science. 2002;298:611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yao T. T., Cohen R. E. A cryptic protease couples deubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Nature. 2002;419:403–407. doi: 10.1038/nature01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bellare P., Kutach A. K., Rines A. K., Guthrie C., Sontheimer E. J. Ubiquitin binding by a variant Jab1/MPN domain in the essential pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp8p. RNA. 2006;12:292–302. doi: 10.1261/rna.2152306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mullally J. E., Chernova T., Wilkinson K. D. Doa1 is a Cdc48 adapter that possesses a novel ubiquitin binding domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:822–830. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.822-830.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Haglund K., Sigismund S., Polo S., Szymkiewicz I., Di Fiore P. P., Dikic I. Multiple monoubiquitination of RTKs is sufficient for their endocytosis and degradation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:461–466. doi: 10.1038/ncb983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mosesson Y., Shtiegman K., Katz M., Zwang Y., Vereb G., Szollosi J., Yarden Y. Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases is driven by monoubiquitylation, not polyubiquitylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21323–21326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang F. T., Kirkpatrick D., Jiang X. J., Gygi S., Sorkin A. Differential regulation of EGF receptor internalization and degradation by multiubiquitination within the kinase domain. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Barriere H., Nemes C., Lechardeur D., Khan-Mohammad M., Fruh K., Lukacs G. L. Molecular basis of oligoubiquitin-dependent internalization of membrane proteins in mammalian cells. Traffic. 2006;7:282–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hawryluk M. J., Keyel P. A., Mishra S. K., Watkins S. C., Heuser J. E., Traub L. M. Epsin 1 is a polyubiquitin-selective clathrin-associated sorting protein. Traffic. 2006;7:262–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alam S. L., Sundquist W. I. Two new structures of Ub–receptor complexes. U2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:186–188. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0306-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hurley J. H., Emr S. D. The ESCRT complexes: structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bonifacino J. S., Traub L. M. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoeller D., Crosetto N., Blagoev B., Raiborg C., Tikkanen R., Wagner S., Kowanetz K., Breitling R., Mann M., Stenmark H., Dikic I. Regulation of ubiquitin-binding proteins by monoubiquitination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:163-U145. doi: 10.1038/ncb1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Panneerselvam S., Marx A., Mandelkow E. M., Mandelkow E. Structure of the catalytic and ubiquitin-associated domains of the protein kinase MARK/Par-1. Structure. 2006;14:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Reverter D., Lima C. D. Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO–RanGAP1–Ubc9–Nup358 complex. Nature. 2005;435:687–692. doi: 10.1038/nature03588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Haglund K., Di Fiore P. P., Dikic I. Distinct monoubiquitin signals in receptor endocytosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]