Abstract

MurG is a peripheral membrane protein that is one of the key enzymes in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. The crystal structure of Escherichia coli MurG (S. Ha, D. Walker, Y. Shi, and S. Walker, Protein Sci. 9:1045-1052, 2000) contains a hydrophobic patch surrounded by basic residues that may represent a membrane association site. To allow investigation of the membrane interaction of MurG on a molecular level, we expressed and purified MurG from E. coli in the absence of detergent. Surprisingly, we found that lipid vesicles copurify with MurG. Freeze fracture electron microscopy of whole cells and lysates suggested that these vesicles are derived from vesicular intracellular membranes that are formed during overexpression. This is the first study which shows that overexpression of a peripheral membrane protein results in formation of additional membranes within the cell. The cardiolipin content of cells overexpressing MurG was increased from 1 ± 1 to 7 ± 1 mol% compared to nonoverexpressing cells. The lipids that copurify with MurG were even further enriched in cardiolipin (13 ± 4 mol%). MurG activity measurements of lipid I, its natural substrate, incorporated in pure lipid vesicles showed that the MurG activity is higher for vesicles containing cardiolipin than for vesicles with phosphatidylglycerol. These findings support the suggestion that MurG interacts with phospholipids of the bacterial membrane. In addition, the results show a special role for cardiolipin in the MurG-membrane interaction.

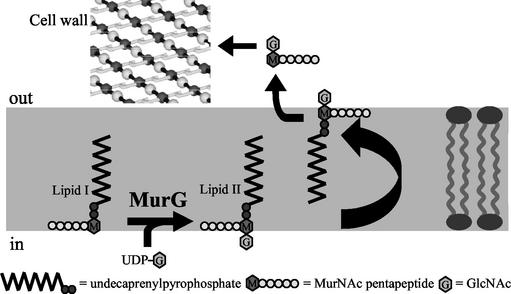

Bacterial cell membranes are surrounded by peptidoglycan, a heteropolymer consisting of glycan strands cross-linked by peptides. An enzyme involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis is the glycosyltransferase MurG. As schematically shown in Fig. 1, the substrate of MurG is lipid I, which consists of an undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate anchored within the membrane and linked to a muramyl pentapeptide. MurG catalyzes the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) from UDP-GlcNAc to lipid I to form lipid II (19). This process takes place on the cytoplasmic surface of the bacterial membrane prior to the translocation of lipid II to the extracellular face of the cell membrane (10). Subsequently, the disaccharide is polymerized and cross-linked to the preexisting peptidoglycan strands of the cell wall (15). This peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway has been shown to be a good target for antibiotics, for example, for the lantibiotic nisin Z, which uses lipid II as a receptor (8, 9).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the role of MurG within the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway. The substrate for MurG is lipid I, which consists of undecaprenylpyrophosphate and the sugar N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) pentapeptide (l-Ala-γd-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala). MurG adds the sugar GlcNAc to lipid I to form lipid II. Subsequently, lipid II is translocated across the cell membrane, after which the disaccharide-pentapeptide is transferred to the peptidoglycan network.

MurG is a moderately hydrophobic protein without any membrane-spanning domain and with a molecular mass of 37,684 Da (19). Based on cell fractionation experiments, it was suggested that the protein is associated with membranes (19). Bupp and Van Heijenoort concluded that MurG is associated with the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane of Escherichia coli, based on the finding that MurG in spheroplasts was insensitive to trypsin (10). The crystal structure of E. coli MurG (14) showed that the protein consists of a C-terminal domain, which probably contains the UDP-GlcNAc-binding site, and an N-terminal domain, which probably contains the lipid I binding site. Additionally, a hydrophobic patch in the N domain, surrounded by basic residues, was found. It was proposed that this is the membrane association site and that association involves both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions with the membrane (14).

To study the membrane interaction of MurG, we expressed the His-tagged protein in E. coli and purified it in the absence of detergent. Surprisingly, we found that lipids in the form of vesicles copurify with MurG. These MurG-lipid vesicles were enriched in the negatively charged lipid cardiolipin (CL). Using freeze fracture electron microscopy (EM), we showed that overexpression of MurG in E. coli results in the formation of vesicular intracellular membranes which contain almost no integral membrane proteins. This is the first time that such intracellular membranes have been observed for overexpression of a peripheral membrane protein. Activity measurements with lipid I-containing vesicles showed that MurG activity is enhanced by the presence of CL. The results suggest that MurG binds to membranes via a direct interaction with the lipids and that it preferentially interacts with CL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS was obtained from The Netherlands Culture Collection of Bacteria. E. coli SD12 (pyrD34 his68 galK35 phoA8 glpD3 glpR2 glpK glpKp) and SD11 (SD12 cls) were first described by Shibuya et al. (26). Lipid I was produced and purified according to the method of Breukink et al. (7) using Micrococcus flavus membrane vesicles, UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide purified from Staphylococcus simulans, and undecaprenylphosphate purified from Laurus nobilus, which was a kind gift of E. Swiezewska. The plasmid pET21b carrying the MurG gene containing a C-terminal LEHHHHHH sequence was a kind gift of S. Walker. MurG without a His tag but with an additional leucine at the C terminus was cloned from MurG containing a C-terminal LEHHHHHH sequence according to the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (Stratagene), which was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose was from Qiagen. His tag monoclonal antibody was obtained from Novagen. 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DOPG), and 1,1′,2,2′-tetraoleoyl CL (TOCL) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. IPTG (isopropylthiogalactoside), UDP-GlcNAc, and n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (octylglucoside) were obtained from Sigma. Uridine diphospho-N-acetyl-d-[U-14C]glucosamine (14C-UDP-GlcNAc; 9.84 GBq/mmol) was purchased from Amersham Pharmacia. DNase and RNase were from Sigma. Lysozyme was obtained from Roche. All other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available.

Expression of MurG.

BL21(DE3)/plysS cells overexpressing MurG (with or without a His tag) from a pET21b vector were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/ml and 25 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. When the optical density at 600 nm reached a value of 0.6, IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The induced cell culture was grown for another 3 h. The cell cultures were then incubated on ice for 15 min and harvested by centrifugation (Sorvall RC3Bplus; H-6000A rotor; 4°C; 30 min; 7,300 × g). The cell pellets were frozen at −20°C.

Purification of His-tagged MurG.

For the purification of His-tagged MurG in the absence of detergent, we modified the protocol described by Ha et al. (14). The cell pellets were thawed at 4°C, and the cells were resuspended in 5 ml of 5 mM imidazole- 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (buffer A), per g of cells and disrupted by forcing them through a French press three times at 12,000 lb/in2. The cell lysate was centrifuged (Sorvall RC5Bplus; Sorvall SS34 rotor; 4°C; 30 min; 4,300 × g), and the supernatant was applied to a Ni-NTA agarose column equilibrated with buffer A. After the column was washed with 25 column volumes of buffer A, the MurG protein was eluted with a stepwise imidazole gradient in buffer A, starting with 15 column volumes of 25 mM imidazole in buffer A, followed by 15 column volumes of 50 mM imidazole in buffer A and 15 column volumes of 100 mM imidazole in buffer A at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The eluted fractions were concentrated with Centricon Plus-20 concentrators (nominal molecular weight limit [NMWL], 10,000; Millipore). The purified MurG was stored at −20°C in the presence of 20% glycerol. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (6).

Preparation of SD11 and SD12 cell lysates.

SD11 and SD12 cells were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium till the optical density at 600 nm reached a value of 0.8. Subsequently, the cells were harvested by centrifugation (Sorvall RC3Bplus; H-6000A rotor; 4°C; 30 min; 7,300 × g) and washed once with physiological salt solution. The cells were resuspended in 5 ml of buffer per g of cells, containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 3% Triton X-100, 4 mM dithiothreitol, 5 mM MgCl2, 40 μg of lysozyme/ml, 20 μg of DNase/ml, and 20 μg of RNase/ml. The cell suspension was incubated on ice for 45 min and subsequently at 37°C for 15 min. The cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation (Sorvall RC5Bplus; SS34 rotor; 4°C; 30 min; 48,000 × g). Finally, the protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein determination kit (Pierce). The most concentrated lysate was diluted to obtain the same protein content for both lysates (dilution factor, 1.4), using a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 3% Triton X-100, 4 mM dithiothreitol, and 5 mM MgCl2.

Enzymatic activity assay.

To determine the enzymatic activity of MurG, an assay was developed, based on a recently developed protocol for the synthesis and purification of lipid II (7). The assay was performed as follows: 50 or 100 ng of MurG was incubated with 3 nmol of lipid I, 10 nmol of UDP-GlcNAc, and 35 pmol of 14C-UDP-GlcNAc in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 6.7 mM MgCl2 and 1% octylglucoside or Triton X-100 in a total volume of 30 μl at room temperature for 1 to 15 min. Lipids were extracted in 60 μl of butanol containing 6.25% pyridine-acetic acid, pH 4.2, which was washed once with 60 μl of water. The amount of lipid II in the butanol-pyridine mixture was determined by liquid scintillation counting. The extraction procedure was validated by thin-layer chromatography on silica plates (Silica gel 60; Merck) using chloroform-methanol-water-ammonia (88:48:10:1, by volume) as eluents, showing that after extraction no detectable amount of lipid II was present in the water phase while no free 14C-UDP-GlcNAc was present in the butanol phase (data not shown).

To test the activity of MurG on lipid vesicles, large unilamellar vesicles (200-nm diameter) were prepared as follows. A dry lipid film containing 1% lipid I was hydrated in 50 mM NaCl- 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The dispersion was frozen and thawed 10 times and extruded 6 times through 200-nm-pore-size membrane filters (Anatop 10; Whatman), essentially as described previously (16). The assay was performed as described above for 100 ng of MurG without the addition of octylglucoside or Triton X-100.

Light scattering.

The size distribution of vesicles was determined by using light scattering by means of a Zetasizer 3000 (Malvern Instruments) using a monomodal analysis mode. As a reference, large unilamellar vesicles with a defined diameter of 100 nm were used, which were prepared as follows. A dry lipid film of DOPE-DOPG-CL (75:20:5) was hydrated in 50 mM NaCl- 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The dispersion was frozen and thawed 10 times and extruded through two stacked 100-nm-pore-size polycarbonate filters (Millipore) as described previously (16).

Freeze fracture EM.

Samples of whole cells were taken from the cell pellet directly after harvesting. Samples of cell lysate and purified MurG were concentrated by Centricon Plus-20 concentrators (10,000 NMWL; Millipore) or ultracentrifugation (Beckman L-60 ultracentrifuge; 60 Ti rotor; 4°C; 90 min; 45,000 × g).

These samples were sandwiched between two hat-shaped copper holders. No cryoprotectants were added. The samples were fast frozen by plunging them into liquid propane, cooled to its melting point with liquid nitrogen, using a KF80 plunge-freezing device (Reichert Jung). The samples were fractured and subsequently replicated with platinum according to standard procedures, using a BAF400 freeze fracture device (Bal-tec AG). The replicas were stripped from the copper holders and cleaned with chromic acid followed by distilled water according to the method of Costello et al. (12). A CM10 electron microscope (Philips) operated at 80 kV was used for examining the replicas.

Phospholipid analysis.

Lipids were extracted according to the method of Bligh and Dyer (5). The phosphorus concentration was determined according to the method of Rouser et al. (24). The phospholipid composition of the lipid extracts was analyzed by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography on silica plates, using chloroform-methanol-water (65:25:4, by volume) for the first dimension and chloroform-methanol-acetic acid (65:25:10, by volume) for the second dimension.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of His-tagged MurG.

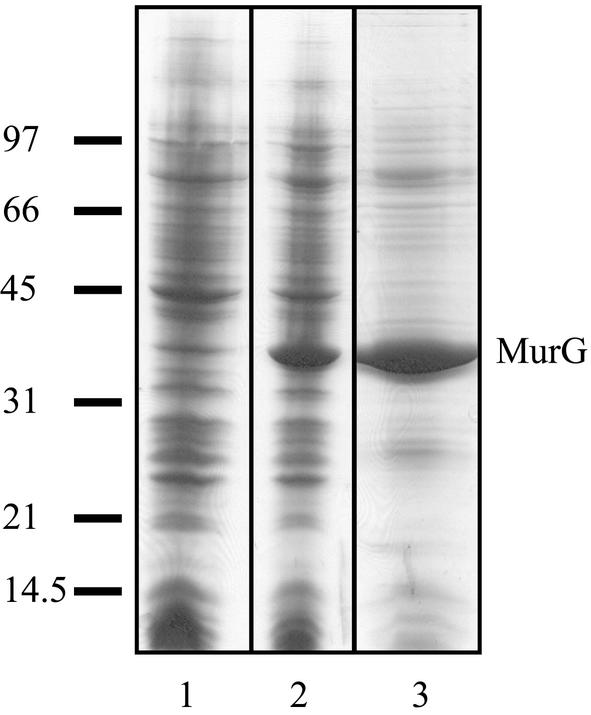

His-tagged MurG was expressed from a pet21b vector in an E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS host. As shown in Fig. 2 (compare lanes 1 and 2), induction with IPTG resulted in the appearance of an intense band on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at a molecular mass of ∼38 kDa, which is the molecular mass of MurG. This protein contained a His tag, as was shown by Western blotting using anti-His tag antibodies (data not shown). Because our aim was to study the membrane interaction of MurG, we wanted to purify the protein in the absence of detergent. Therefore, we set up a new purification procedure, using a Ni-NTA column with an imidazole gradient. The result of the purification is shown in Fig. 2, lane 3. The yield of purified protein was ∼5 mg per liter of cells. The enzymatic activity of His-tagged MurG in 1% octylglucoside was determined to be 10.2 ± 2.7 μmol/min/mg of protein. This is much higher than the value of 2.8 nmol/min/mg of protein published earlier by Crouvoisier et al. (13). This difference is probably due to different assay conditions, since we used pure lipid I while Crouvoisier et al. used E. coli membranes (13). Addition of 20% glycerol before storage at −20°C was found to be necessary to keep MurG enzymatically active (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Expression and purification of His-tagged MurG. Lane 1, E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells containing the pet21b+MurG vector before IPTG induction; lane 2, E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells containing the pet21b+MurG vector 3 h after IPTG induction, just before harvesting; lane 3, purified MurG. A protein size marker is shown on the left.

Phospholipids copurify with His-tagged MurG.

Based on a phosphate determination after Bligh and Dyer extraction, we found that the solution of purified His-tagged MurG still contained phospholipids. The lipid composition was determined and is shown in Table 1. We found that the lipids that copurify with His-tagged MurG are enriched in CL compared to the total lipid extract of nonoverexpressing cells: the CL content is increased from between 1 and 2 to 13 mol%. Furthermore, the total lipid extract of His-tagged MurG-overproducing cells also shows enrichment of CL, but to a lesser extent: the CL content was found to be 7 mol%.

TABLE 1.

Phospholipid composition of phospholipid extracts of purified MurG and E. coli cells with and without MurG overexpressiona

| Phospholipid extract | Phospholipid composition (mol%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PEf | PG | CL | |

| Purified MurGb | 66 ± 7 | 21 ± 4 | 13 ± 4 |

| Nonoverexpressing cells (MurG vector; no IPTG)c | 75 ± 4 | 24 ± 4 | 1 ± 1 |

| Nonoverexpressing cells (empty vector; + IPTG)d | 69 ± 2 | 29 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

| MurG-overexpressing cells (MurG vector; + IPTG)e | 75 ± 2 | 18 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 |

See Materials and Methods for the exact description of MurG expression and purification, lipid extraction, and determination of the phospholipid composition. Standard deviations are based on at least three independent measurements.

Lipid extract of MurG.

Total lipid extract of cells containing the plasmid pet21b+MurGhistag without induction by IPTG.

Total lipid extract of cells containing the plasmid pet21b with induction by IPTG.

Total lipid extract of cells containing the plasmid pet21b+MurGhistag with induction by IPTG.

PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

The question then arose as to the form in which the lipids in association with MurG are present in the solution: as vesicles or as molecular complexes with His-tagged MurG. To get a first indication about the aggregation form of the lipids, we used dynamic light scattering. We observed that particles were present in a solution of purified His-tagged MurG. We found that the particles had an average diameter of 130 nm, with a polydispersity index of 0.36 (data not shown). This large size suggests that the particles represent lipids that are present as lipid vesicles, but the possibility that they represent large protein aggregates cannot be excluded.

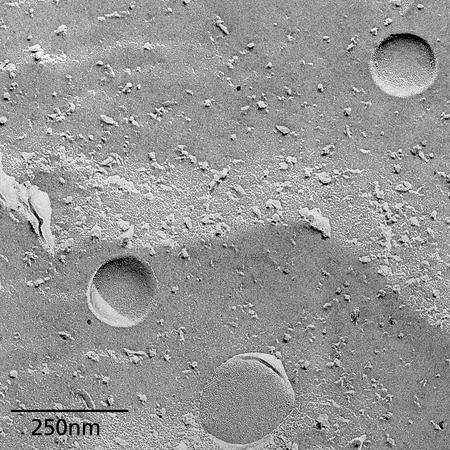

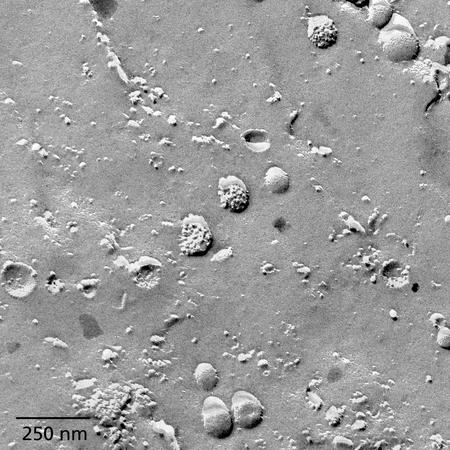

To further investigate the nature of these particles, we therefore used freeze fracture EM. The result is shown in Fig. 3. This EM picture shows the presence of spherical particles with smooth fracture faces, typical of lipid vesicles. The size of these vesicles, which have an average diameter of 148 ± 87 nm (n = 15), is in agreement with the size of the particles as determined by dynamic light scattering. These results demonstrate that the lipids that copurify with His-tagged MurG are present as lipid vesicles.

FIG. 3.

Freeze fracture electron micrograph of purified MurG with copurified lipids.

Quantification of the phospholipid content in the solution of purified MurG showed that the phospholipid-to-protein molar ratio was 4.5 ± 1.5 (assuming one phosphate per phospholipid). Since this ratio is quite low, the question arises whether all MurG molecules are bound to these vesicles. One MurG molecule covers at least 20 phospholipid molecules (an estimation based on the crystal structure of MurG [14]), indicating that it is not possible that all MurG molecules are bound to these vesicles via a lipid-protein interaction. We suggest that some MurG molecules are directly bound to the lipid vesicles while others are bound in an additionally adsorbed layer via protein-protein interactions, as was shown before for apocytochrome c (23).

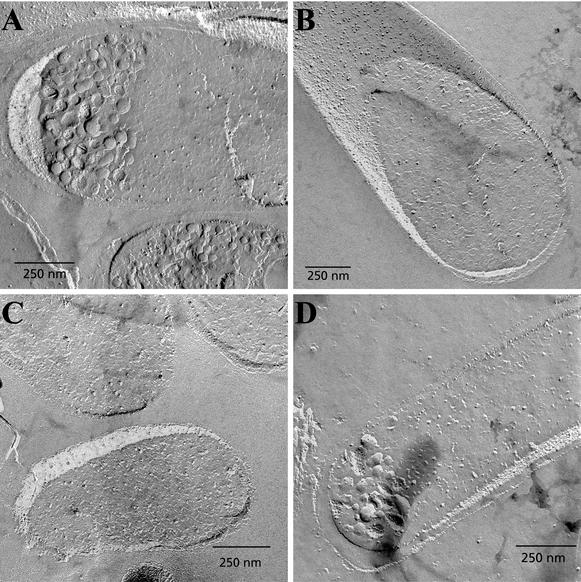

Lipid vesicles in overexpressing cells and lysate.

When are these lipid vesicles formed? To get an indication whether this occurs during cell lysis or within the cell during overexpression of His-tagged MurG, we again used freeze fracture EM. Figure 4A shows a micrograph of an E. coli cell that overexpresses His-tagged MurG. It can be seen that additional membranes are present in the cytosol of the cell which in the microscope have the appearance of vesicles. Most of the vesicles in the cell have smooth surfaces, indicating that they contain almost no integral membrane proteins. Strikingly, these vesicles seem to accumulate at the cell poles. The average diameter of the vesicles is 53 ± 16 nm (n = 22). Such vesicles were not observed in cells without overexpression or with induction of an empty vector (Fig. 4B and C). Control experiments, in which the His tag was removed by site-directed mutagenesis, showed that for MurG without a His tag, overexpression of this protein also results in the formation of vesicles in the cell (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Freeze fracture electron micrographs of cells. (A) E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells carrying the pet21b+MurGhistag plasmid with IPTG induction. (B) E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells carrying the pet21b+MurGhistag plasmid without IPTG induction. (C) E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells carrying the empty pet21b plasmid with IPTG induction. (D) E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells carrying the pet21b+MurG (without His tag) plasmid with IPTG induction.

The cell lysate after French pressure contained a mixture of smooth vesicles and vesicles with intramembranous particles (Fig. 5). These intramembranous particles are interpreted as reflecting the presence of intrinsic membrane proteins (30). The high density of these intramembranous particles is typical for inner membrane vesicles (4). The smooth vesicles were not present in the lysate of cells without MurG overexpression (data not shown) but only in the lysate of His-tagged MurG-overexpressing cells (the lysate of cells overexpressing MurG without a His tag was not tested).

FIG. 5.

Freeze fracture electron micrograph of lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3)/plysS cells carrying the pet21b+MurGhistag plasmid with IPTG induction.

These data strongly indicate that the vesicles that copurify with His-tagged MurG originate from the additional membranes that are formed within the cell during overexpression. The size difference between the vesicles within the cell (±53 nm) (Fig. 4A) and the vesicles copurified with His-tagged MurG (±148 nm) (Fig. 3) might be caused by the process of cell lysis and a lower osmotic pressure during purification by affinity chromatography that possibly caused fusion of the vesicles into larger ones.

Role of CL.

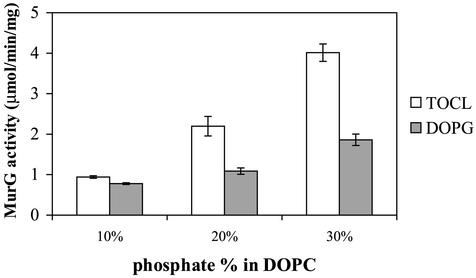

Overexpression of MurG resulted in enrichment of CL. To test the possibility that this was due to a specific interaction of MurG with CL, we determined the effect of CL on the enzymatic activity of His-tagged MurG. We measured the enzymatic activity of MurG on lipid I incorporated in large unilamellar vesicles. We mixed TOCL with DOPC to obtain stable bilayers. As a reference, we used vesicles of DOPC and DOPG, which, like CL, is an anionic lipid. The results are shown in Fig. 6. A larger amount of lipid II was formed when more (anionic) CL or phosphatidylglycerol (PG) was incorporated in the (zwitterionic) phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Furthermore, we observed a significantly higher MurG activity in the presence of CL than in the presence of PG, indicating that there is not only a general effect of anionic lipids but also a special interaction between MurG and CL. To gain insight into the physiological relevance of this interaction, we used the E. coli strain SD11, which has a defective CL synthase, resulting in a CL content of 0.1% (26). The growth rate of SD11 is only slightly lower than the growth rate of SD12 (1.68 versus 1.76 turbidity doublings/h [26]), indicating that the cell wall synthesis is at a normal level. If CL is important for the function of MurG, it could be that SD11 compensates for the lower enzymatic activity of MurG, due to the absence of CL, by upregulation of the amount of MurG. To get an indication of MurG upregulation, we measured the enzymatic activity of MurG in cell lysate under conditions where the difference in phospholipid composition had no effect. This was possible in the presence of 1% Triton X-100 (data not shown). We measured for SD11 lysate an enzymatic activity of 0.67 ± 0.05 nmol/min/mg and for SD12 lysate an enzymatic activity of 0.43 ± 0.04 nmol/min/mg. This suggests that MurG may indeed be upregulated in SD11 cells due to the absence of CL. This supports our idea that CL is important for the function of MurG.

FIG. 6.

MurG activity on lipid I incorporated in pure lipid vesicles. His-tagged MurG (100 ng) was incubated with 0.3 μmol of lipid vesicles containing 2 Pi% lipid I and a certain percentage of TOCL or DOPG normalized for the amount of phosphate. This was done for 0.5 to 16 min at room temperature in the presence of 0.33 mM UDP-GlcNAc (of which 1% was 14C labeled), 6.7 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, and 50 mM NaCl. All measurements were performed in duplicate. The MurG activity was calculated as the amount of lipid II formed per min per mg of protein, based on the trend line through the data points. The error bars indicate standard deviations based on two or three measurements.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that MurG overexpression results in the formation of additional membranes within the cell and enrichment of CL. Furthermore, we observed that lipids, further enriched in CL, copurified with MurG, and we obtained strong indications of a specific interaction between MurG and CL.

The observation that overexpression results in the formation of additional membrane structures within the cell is rather striking. Similar observations were done previously for various other proteins, such as fumarate reductase (34), membrane-bound ATP synthase (32), sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (35), LamB-LacZ hybrid proteins (33), sp6.6 (2), and the b subunit of F1Fo ATP synthase (1). However, these proteins are all integral membrane proteins, which need a membrane to be expressed in a functional form. This is the first time that such an effect has been shown for a peripheral membrane protein. This suggests that for overexpression of MurG as well, the membrane is important. Because of that, we conclude that in E. coli most of the overexpressed MurG is probably bound to the vesicles.

The membrane structures in MurG-overexpressing cells have smooth surfaces. This is also the case for the vesicles that copurified with MurG, indicating that they do not contain any integral membrane protein. Therefore, we suggest that the overexpressed MurG is bound to these vesicles via a direct interaction with the lipids and not via a (specific) interaction with an integral membrane protein. This is supported by the fact that MurG is able to use lipid I as a substrate, even when it is incorporated in vesicles composed of only lipids (Fig. 6). It is also in agreement with the suggestion of Ha and coworkers (14) that MurG is bound to the membrane via a hydrophobic patch surrounded by basic residues. Moreover, this protein shows a certain similarity with the catalytic domain of leader peptidase, which contains a large exposed hydrophobic patch as a membrane association surface (21). It has been shown by our group that this protein can bind to pure lipid membranes (27, 28).

The additional membranes in MurG-overexpressing cells accumulate at the cell poles. It is known that the cell poles are metabolically silent immediately after their formation (31). Therefore, it is not likely that MurG itself preferentially localizes there. We suggest that the localization of the vesicles (with MurG) at the cell poles is due to the process of overexpression, since most cytosolic free space is probably located at these sites. However, no cell pole localization was observed in the cases of the membrane proteins that were also overexpressed in additional membrane structures (1, 2, 32-35).

We obtained several indications of a specific interaction between MurG and CL. First, we observed that overexpression of MurG resulted in enrichment of CL. This was even more obvious in the lipids that copurified with MurG. Such enrichment was also shown for cells overexpressing f1 bacteriophage coat protein, for which a specific association with CL was also suggested (11). However, this enrichment could also be affected by several other factors, such as the putative cell pole localization of MurG, since it has been shown that CL is enriched on the cell poles (18, 20). Also, a physiological effect of the formation of additional membranes upon overexpression could play a role, since the overexpression of the integral membrane proteins fumarate reductase (34) and the b subunit of F1Fo ATP synthase (1) was also accompanied by membrane formation and CL enrichment. However, more indications of an interaction between MurG and CL were found. First, we measured a higher enzymatic activity of MurG on lipid I in vesicles containing CL than in vesicles containing PG. Second, we observed a significantly higher MurG activity in the lysate of cells with a defective CL synthase, which could be an indication of upregulation of MurG in these cells.

MurG contains a hydrophobic patch surrounded by basic residues, which was proposed to be the membrane association site (14). These basic residues might interact preferentially with the negatively charged head group of CL. However, because the SD11 strain (with only 0.1% CL) has only a slightly lower growth rate than the wild-type strain (26) while MurG is an essential protein (19), we conclude that CL is not essential for the action of MurG. The increased activity of MurG in the presence of CL relative to that in the presence of PG could be related to the fact that CL has two negative charges at defined positions close to each other, while PG has only one negative charge. Possibly, the fact that CL behaves as a nonbilayer lipid in the presence of divalent cations (25, 29) could also be important. It has been shown that the small head group of nonbilayer lipids results in the formation of interfacial insertion sites that are thought to be important for membrane binding of the catalytic domain of leader peptidase (27). Possibly, the interaction between MurG and CL also provides the cell a potential means of controlling peptidoglycan biosynthesis via regulation of the CL content. In a similar way, it has been suggested that the control of mitochondrial respiration by thyroid hormones is exerted at the level of CL synthase (17), with changes in the CL content leading to changes in the activities of major proteins, such as cytochrome c oxidase (22). Controlling peptidoglycan biosynthesis via regulation of MurG would be possible, since there are indications that MurG performs the rate-limiting step within this pathway (3).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. J. Verkleij for the use of and help with freeze fracture EM.

This work was supported by the Dutch Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter (FOM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arechaga, I., B. Miroux, S. Karrasch, R. Huijbregts, B. de Kruijff, M. J. Runswick, and J. E. Walker. 2000. Characterisation of new intracellular membranes in Escherichia coli accompanying large scale over-production of the b subunit of F1Fo ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 482:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armour, G. A., and G. J. Brewer. 1990. Membrane morphogenesis from cloned fragments of bacteriophage PM2 DNA that contain the sp6.6 gene. FASEB J. 4:1488-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbosa, M. D., H. O. Ross, M. C. Hillman, R. P. Meade, M. G. Kurilla, and D. L. Pompliano. 2002. A multitarget assay for inhibitors of membrane-associated steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Anal. Biochem. 306:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer, M. E., M. Dolack, and E. Houser. 1977. Effects of lipid phase transition of the freeze-cleaved envelope of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 129:1563-1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bligh, E. G., and W. J. Dyer. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breukink, E., H. E. Van Heusden, P. J. Vollmerhaus, E. Swiezewska, L. Brunner, S. Walker, A. J. R. Heck, and B. De Kruijff. Lipid II is an intrinsic component of the pore induced by nisin in bacterial membranes. J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Breukink, E., I. Wiedemann, C. van Kraaij, O. P. Kuipers, H. Sahl, and B. de Kruijff. 1999. Use of the cell wall precursor lipid II by a pore-forming peptide antibiotic. Science 286:2361-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brotz, H., M. Josten, I. Wiedemann, U. Schneider, F. Gotz, G. Bierbaum, and H. G. Sahl. 1998. Role of lipid-bound peptidoglycan precursors in the formation of pores by nisin, epidermin and other lantibiotics. Mol. Microbiol. 30:317-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bupp, K., and J. van Heijenoort. 1993. The final step of peptidoglycan subunit assembly in Escherichia coli occurs in the cytoplasm. J. Bacteriol. 175:1841-1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain, B. K., and R. E. Webster. 1976. Lipid-protein interactions in Escherichia coli. Membrane-associated f1 bacteriophage coat protein and phospholipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 251:7739-7745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costello, M. J., R. Fetter, and M. Hochli. 1982. Simple procedures for evaluating the cryofixation of biological samples. J. Microsc. 125:125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crouvoisier, M., D. Mengin-Lecreulx, and J. van Heijenoort. 1999. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:N-acetylmuramoyl-(pentapeptide) pyrophosphoryl undecaprenol N-acetylglucosamine transferase from Escherichia coli: overproduction, solubilization, and purification. FEBS Lett. 449:289-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha, S., D. Walker, Y. Shi, and S. Walker. 2000. The 1.9 Å crystal structure of Escherichia coli MurG, a membrane-associated glycosyltransferase involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Protein Sci. 9:1045-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtje, J. V. 1998. Growth of the stress-bearing and shape-maintaining murein sacculus of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:181-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hope, M. J., M. B. Bally, G. Webb, and P. R. Cullis. 1985. Production of large unilamellar vesicles by a rapid extrusion procedure. Characterization of size distribution, trapped volume and ability to maintain a membrane potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 812:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hostetler, K. Y. 1991. Effect of thyroxine on the activity of mitochondrial cardiolipin synthase in rat liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1086:139-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koppelman, C. M., T. Den Blaauwen, M. C. Duursma, R. M. Heeren, and N. Nanninga. 2001. Escherichia coli minicell membranes are enriched in cardiolipin. J. Bacteriol. 183:6144-6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mengin-Lecreulx, D., L. Texier, M. Rousseau, and J. van Heijenoort. 1991. The murG gene of Escherichia coli codes for the UDP-N-acetylglucosamine:N-acetylmuramyl-(pentapeptide) pyrophosphoryl-undecaprenol N-acetylglucosamine transferase involved in the membrane steps of peptidoglycan synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 173:4625-4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mileykovskaya, E., and W. Dowhan. 2000. Visualization of phospholipid domains in Escherichia coli by using the cardiolipin-specific fluorescent dye 10-N-nonyl acridine orange. J. Bacteriol. 182:1172-1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paetzel, M., R. E. Dalbey, and N. C. Strynadka. 1998. Crystal structure of a bacterial signal peptidase in complex with a beta-lactam inhibitor. Nature 396:186-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paradies, G., F. M. Ruggiero, P. Dinoi, G. Petrosillo, and E. Quagliariello. 1993. Decreased cytochrome oxidase activity and changes in phospholipids in heart mitochondria from hypothyroid rats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 307:91-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilon, M., W. Jordi, B. De Kruijff, and R. A. Demel. 1987. Interactions of mitochondrial precursor protein apocytochrome c with phosphatidylserine in model membranes. A monolayer study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 902:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouser, G., S. Fkeischer, and A. Yamamoto. 1970. Two dimensional thin layer chromatographic separation of polar lipids and determination of phospholipids by phosphorus analysis of spots. Lipids 5:494-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlame, M., D. Rua, and M. L. Greenberg. 2000. The biosynthesis and functional role of cardiolipin. Prog. Lipid Res. 39:257-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibuya, I., C. Miyazaki, and A. Ohta. 1985. Alteration of phospholipid composition by combined defects in phosphatidylserine and cardiolipin synthases and physiological consequences in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 161:1086-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van den Brink-van der Laan, E., R. E. Dalbey, R. A. Demel, J. A. Killian, and B. De Kruijff. 2001. Effect of nonbilayer lipids on membrane binding and insertion of the catalytic domain of leader peptidase. Biochemistry 40:9677-9684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Klompenburg, W., M. Paetzel, J. M. de Jong, R. E. Dalbey, R. A. Demel, G. von Heijne, and B. de Kruijff. 1998. Phosphatidylethanolamine mediates insertion of the catalytic domain of leader peptidase in membranes. FEBS Lett. 431:75-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vasilenko, I., B. De Kruijff, and A. J. Verkleij. 1982. Polymorphic phase behaviour of cardiolipin from bovine heart and from Bacillus subtilis as detected by 31P-NMR and freeze-fracture techniques. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, Ba2+ and temperature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 684:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verkleij, A. J., and P. H. Ververgaert. 1981. The nature of the intramembranous particle. Acta Histochem. Suppl. 23:137-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vollmer, W., and J. V. Holtje. 2001. Morphogenesis of Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:625-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Meyenburg, K., B. B. Jorgensen, and B. van Deurs. 1984. Physiological and morphological effects of overproduction of membrane-bound ATP synthase in Escherichia coli K-12. EMBO J. 3:1791-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voorhout, W., T. De Kroon, J. Leunissen-Bijvelt, A. Verkleij, and J. Tommassen. 1988. Accumulation of LamB-LacZ hybrid proteins in intracytoplasmic membrane-like structures in Escherichia coli K12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:599-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiner, J. H., B. D. Lemire, M. L. Elmes, R. D. Bradley, and D. G. Scraba. 1984. Overproduction of fumarate reductase in Escherichia coli induces a novel intracellular lipid-protein organelle. J. Bacteriol. 158:590-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkison, W. O., J. P. Walsh, J. M. Corless, and R. M. Bell. 1986. Crystalline arrays of the Escherichia coli sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, an integral membrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9951-9958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]