Abstract

Root hair development in plants is controlled by many genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors. A number of genes have been shown to be important for root hair formation. Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive 4 mutants were originally identified by screening for NaCl-hypersensitive growth. The SOS4 (Salt Overly Sensitive 4) gene was recently isolated by map-based cloning and shown to encode a pyridoxal (PL) kinase involved in the production of PL-5-phosphate, which is an important cofactor for various enzymes and a ligand for certain ion transporters. The root growth of sos4 mutants is slower than that of the wild type. Microscopic observations revealed that sos4 mutants do not have root hairs in the maturation zone. The sos4 mutations block the initiation of most root hairs, and impair the tip growth of those that are initiated. The root hairless phenotype of sos4 mutants was complemented by the wild-type SOS4 gene. SOS4 promoter-β-glucuronidase analysis showed that SOS4 is expressed in the root hair and other hair-like structures. Consistent with SOS4 function as a PL kinase, in vitro application of pyridoxine and pyridoxamine, but not PL, partially rescued the root hair defect in sos4 mutants. 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid treatments promoted root hair formation in both wild-type and sos4 plants, indicating that genetically SOS4 functions upstream of ethylene and auxin in root hair development. The possible role of SOS4 in ethylene and auxin biosynthesis is discussed.

Root hairs have been employed as a useful model to study the underlying mechanisms of cell patterning, cell differentiation, and cell growth in higher plants (Schiefelbein, 2000). Root hairs form from single root epidermal cells, are easy to observe, and follow a precise morphogenetic pathway, providing a simple tool to study the fundamental features of development. Root hair development can be divided into four stages: cell specification, root hair initiation, tip growth, and maturation (Gilroy and Jones, 2000). During root development in most plant species, root hairs grow out of a specialized subset of epidermal cells called trichoblasts (Peterson and Farquhar, 1996). In the trichoblast, root hair initiation becomes evident by the formation of a highly localized bulge in the cell wall. After initiation, the root hair extends by tip growth, leading to an elongated hair-like morphology.

Much progress has been made on the genetic analysis of root hair development in Arabidopsis. Through mutational analysis, several genes have been defined in Arabidopsis that function in the specification of root epidermal cell types. Among those, the TTG and GL2 genes are the best characterized and function in both the root and shoot as epidermal developmental regulators. TTG encodes a small protein with WD40 repeats and is likely to be an early acting component in the cell specification process because ttg mutations alter all aspects of hair cell differentiation (Galway et al., 1994; Berger et al., 1998; Walker et al., 1999). Both ttg and gl2 mutants possess root hairs on nearly all root epidermal cells. GL2 encodes a homeodomain transcription factor that is preferentially expressed in the differentiating non-hair epidermal cells (Rerie et al., 1994; Di Cristina et al., 1996). TTG is one of the important activators of GL2 because the expression of GL2 is markedly reduced in the ttg background (Hung et al., 1998). WER is also a well-characterized gene that functions in root hair specification. Mutations in the WER gene cause nearly all root epidermal cells to differentiate into root hair cells. WER encodes a MYB-type transcription factor and was proposed to directly regulate GL2 transcription (Hung et al., 1998; Lee and Schiefelbein, 1999). Another MYB-like protein encoded by the CPC gene has been shown to be a positive regulator of root hair cell specification (Wada et al., 1997).

Mutants with altered root hair initiation are defined by a cytologically normal pattern of epidermal cells but abnormal number of root hairs. The mutants identified to date indicate that root hair initiation is regulated by hormones such as auxin and ethylene. For example, auxin response mutants axr2 (Wilson et al., 1990) and axr3 (Leyser et al., 1996) produce very few root hairs, although early cell specification is normal. The ethylene response mutant, ctr1, possesses ectopic root hairs. CTR1 encodes a Raf-like protein kinase that negatively regulates ethylene signaling (Kieber et al., 1993). The rhd6 root hair development mutant, which fails to initiate root hairs correctly, can be rescued by application with the ethylene precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA; Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994). Moreover, ACC induces some ectopic root hair formation (Tanimoto et al., 1995; Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1996; Pitts et al., 1998), but aminoethoxyvinyl-Gly, an ethylene biosynthesis inhibitor, abolishes root hair formation in wild-type Arabidopsis (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994; Tanimoto et al., 1995). In Arabidopsis, root hairs are always localized at the apical end of the epidermal cells. However, the position of root hair formation is shifted in axr2, etr1 (ethylene resistant 1), eto1 (ethylene overproducer 1), and rhd6 mutants (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994), again suggesting that these hormones are critical regulators of root hair formation.

The tip growth right after initiation and bulge formation of root hair is due to the deposition of cell membranes and wall materials at a restricted tip area of the plasma membrane (Schnepf, 1986). Many Arabidopsis genes affecting this process have been identified through mutant analysis (Parker et al., 2000). Among them, the RHD2 gene appears to be specifically required for the initiation of root hair tip growth because rhd2 mutants possess bulges of the proper size and location but lack subsequent hair elongation (Schiefelbein and Somerville, 1990). The TRH1 (Tiny Root Hair 1) gene is required for root tip growth and was cloned recently and shown to encode a potassium transporter (Rigas et al., 2001). The trh1 mutants form initiation sites but fail to undergo tip growth, implicating potassium-related turgor pressure in the elongation of root hairs. Several other loci are required for root hair tip growth, including COW1, RHD3, RHD4, TIP1, WAVY, KOJAK/AtCSLD3, and LRX1. Mutations in these genes result in altered root hair morphology, generating swollen, branched, wavy, or other defective shapes. RHD3 encodes a protein with GTP-binding motifs that may be required during vacuole enlargement, illustrating the critical role of this process in root hair tip growth (Wang et al., 1997). The recent isolation and functional characterization of KOJAK/AtCSLD3, a cellulose synthase-like protein (Favery et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001), and LRX1, a chimeric Leu-rich repeat/extensin cell wall protein (Baumberger et al., 2001), revealed the importance of cell wall components on the regulation of root hair morphology and elongation. After the demonstration of the central role of AtRop1 and AtRac2 on pollen tube tip growth (Zheng and Yang, 2000), the Rop GTPases, AtRop4 and AtRop6, were found to affect the tip growth of root hairs (Molendijk et al., 2001).

Recently, we reported the characterization and isolation of the Arabidopsis SOS4 (Salt Overly Sensitive 4) gene (Shi et al., 2002). sos4 mutants were recovered based on their NaCl-hypersensitive phenotype. The growth of sos4 mutant plants showed enhanced sensitivity to inhibition by high concentrations of NaCl. Under NaCl stress, sos4 plants accumulate more Na+ and retain less K+ compared with wild-type plants. SOS4 encodes a pyridoxal (PL) kinase that is involved in the biosynthesis of PL-5-phosphate (PLP), an active form of vitamin B6 (Shi et al., 2002). Besides being a cofactor for many cellular enzymes, PLP is known to be a ligand that regulates the activity of certain ion transporters in animal cells. This latter property may be related to the salt tolerance function of SOS4 (Shi et al., 2002).

Here, we describe a novel morphological phenotype of sos4. sos4 mutants are defective in root hair initiation and tip growth. This root hair defect was complemented by the wild-type SOS4 gene. In vitro application of pyridoxine (PN) and pyridoxamine (PM), but not PL, partially rescued the root hair defect in sos4 mutants. This observation indicates that impaired PL kinase activity is the cause of the root hairless phenotype of sos4 mutants. ACC and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) also can partially rescue the sos4 root hair phenotype, suggesting that this function of SOS4 is related to auxin and ethylene regulation of root hair development.

RESULTS

sos4 Mutants Are Defective in Root Hair Development

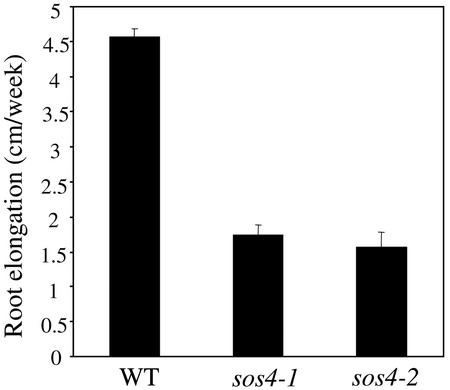

sos4 mutants were initially isolated by screening for NaCl-hypersensitive growth, using a root-bending assay (Shi et al., 2002). sos4 plants are hypersensitive to Na+, Li+, and K+ treatments. Molecular cloning revealed that SOS4 encodes a PL kinase, which is involved in the biosynthesis of PLP (Shi et al., 2002). Under normal growth conditions, the aerial parts of sos4 mutants are indistinguishable from the wild type but the roots of the mutants grow more slowly than wild-type roots (Shi et al., 2002). sos4 mutant seedlings grew into normal fertile plants with normal seed set. Figure 1 shows the root growth rates of sos4 mutants and wild-type seedlings. On Murashige and Skoog nutrient medium, the root growth of both sos4-1 and sos4-2 was reduced by about 60% compared with that of wild type (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Elongation rates of primary roots in sos4 mutant and wild-type plants. Four-day-old seedlings grown vertically on Murashige and Skoog agar medium were marked at the root tips and the extent of new root growth was measured 7 d later. Error bars represent sds (n = 15).

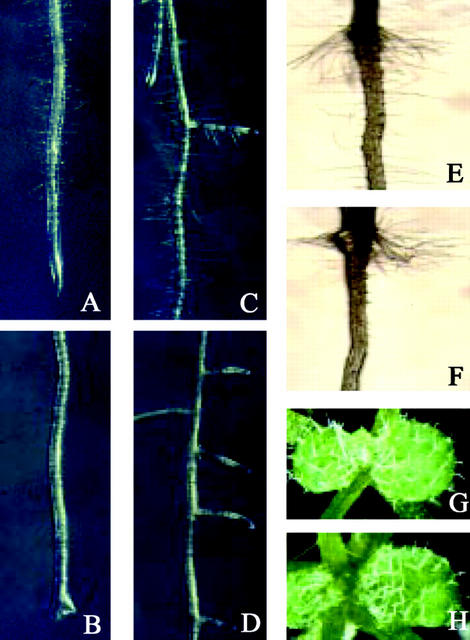

Observations of the mutant roots under a microscope revealed that sos4 mutants have a root hair defect. Because sos4-1 and sos4-2 mutants show identical mutant phenotypes, only the sos4-1 phenotype is shown (Fig. 2). sos4 mutants failed to form root hairs at the maturation zone near the root tip and at the older part of primary root with lateral roots (Fig. 2, B and D), as compared with the normal root hair formation in wild-type plants (Fig. 2, A and C). However, sos4 mutants show normal formation of root hairs at the root-hypocotyl junction, as the wild type does (Fig. 2, E and F). Because sos4 mutants are in the Columbia gl1 background that does not have trichomes, the mutants were crossed with Columbia wild type (GL1) to determine whether the mutations affect trichome development. Homozygous sos4-1 mutants with trichomes on their leaves were found in the F2 population derived from the crosses. There were no changes in the shape and spacing of trichomes in the leaf epidermis of sos4 mutants compared with the GL1/SOS4 wild type (Fig. 2, G and H). These results indicate that SOS4 is not required for trichome development.

Figure 2.

Phenotypes of wild-type and sos4 mutant visualized by a stereomicroscope. A, C, E, and G, Wild type. B, D, F, and H, sos4-1 mutant. A and B, Primary root with root tip, showing a lack of root hair formation in the maturation zone in sos4-1. C and D, Two-week-old primary root with lateral roots. E and F, Root hair formation in the root-hypocotyl junction region. G and H, Young leaves of 2-week-old seedlings, showing trichome morphology.

Backcrosses of sos4-1 plants to the wild type produced F1 plants with a wild-type root hair phenotype. An approximately 3:1 segregation of wild-type versus mutant root hair phenotypes was observed in the F2 population generated from the F1 plants (data not shown), indicating that the sos4-1 root hair mutation is recessive and in a single nuclear locus.

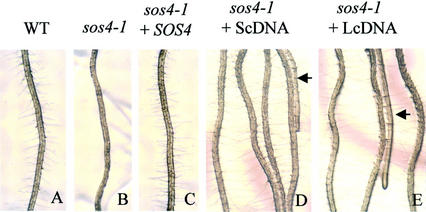

To determine whether mutations in the SOS4 gene are responsible for the sos4 root hairless phenotype, complementation tests were performed. As shown in Figure 3, transgenic plants harboring an approximately 7.0-kb genomic fragment spanning the entire SOS4 gene and transgenic plants overexpressing SOS4 cDNA show normal root hair formation. Cosegregation of the transgenes and the root hair phenotype in the F2 transgenic plants was confirmed by PCR analysis of the transgenes (data not shown). These results clearly demonstrate that the root hair-defective phenotype in sos4 mutant plants is caused by a mutation in the SOS4 gene.

Figure 3.

SOS4 complements the root hair-defective phenotype of sos4 mutant. A, Wild-type primary root with visible root hairs. B, sos4-1 primary root showing no root hair formation. C, Root of a representative T2 transgenic sos4-1 mutant transformed with an approximately 7.0-kb genomic fragment containing the wild-type SOS4 gene. D, T2 transgenic line of sos4-1 mutant transformed with the short cDNA (ScDNA) of SOS4 under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. E, T2 transgenic line of sos4-1 mutant transformed with the long cDNA (LcDNA) of SOS4 driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter. Arrows point to sos4 mutants segregated from the T2 transgenic lines.

SOS4 Is Required for the Initiation and Tip Growth of Root Hairs

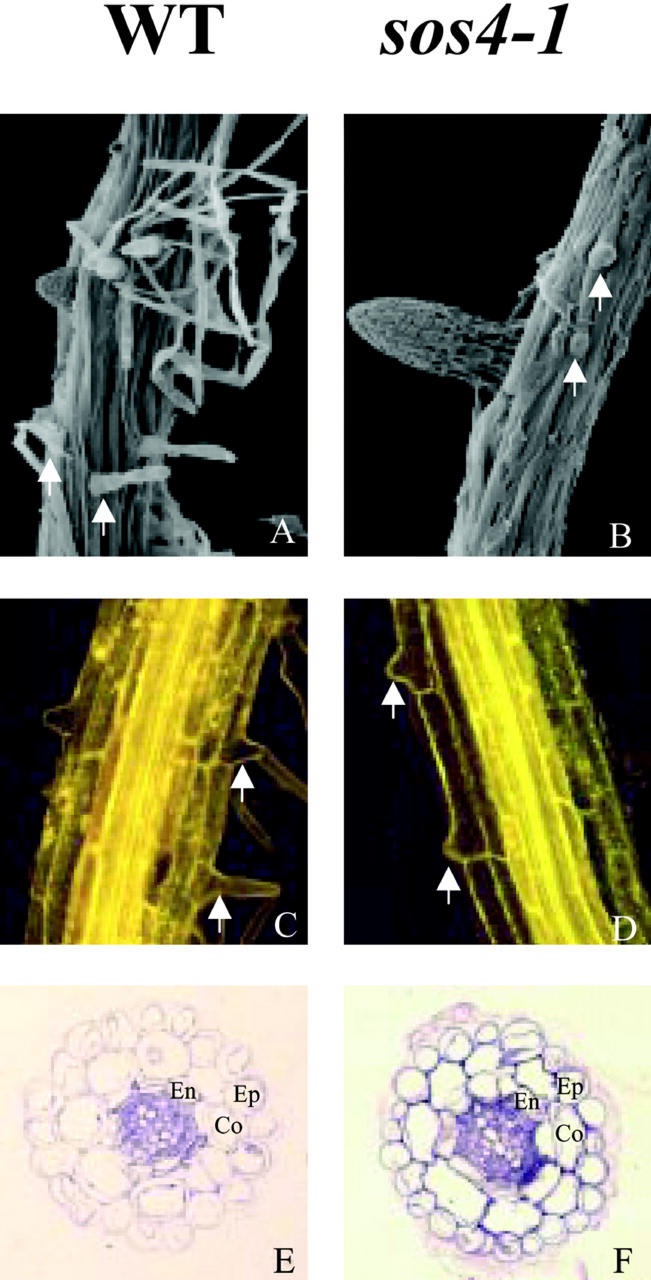

Root hair development occurs in four phases: cell fate specification, initiation, tip growth, and maturation (Gilroy and Jones, 2000). To determine which stage of root hair development is arrested in sos4 mutant plants, scanning microscopy was employed to visualize the formation of root hairs. In wild-type plants, epidermal cells in the region of primary root where lateral roots emerge produce many elongated mature root hairs (Fig. 4A). However, sos4 mutant roots have only a few occasional bulges on the epidermal cells in this region (Fig. 4B). This indicates that the sos4 mutation results in the reduction in root hair initiation and arrest in tip growth. Pollen tube growth is not defective in sos4 mutants, although this cell type also undergoes tip growth (data not shown). During normal root hair development, the trichoblast produces highly localized expansion to form a bulge at the apical end of the cell, from which a tip-growing hair emerges. The site of root hair initiation on the lateral wall of the trichoblast is precisely regulated in Arabidopsis wild-type plants (Fig. 4C). Although the root hair elongation is arrested in sos4 mutants once root hair initiation is completed in some epidermal cells, the initiation site of root hair is correctly localized at the apical end (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Root hair development is arrested at the stage of initiation and tip growth in sos4-1 mutant. A, C, and E, Wild type. B, D, and F, sos4-1 mutant. A and B, Primary root visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). C and D, Primary root visualized by confocal microscopy after fluorescent brightener staining. E and F, Thin section of primary root. Arrows point to root hairs or hair initials. Ep, Epidermis; Co, cortex; En, endodermis.

In Arabidopsis, the number of cell files in each root tissue layer is relatively constant (Schneider et al., 1997). Because the mutations in SOS4 gene affect both normal root growth and root hair development, the structure of the primary root was investigated. In both wild-type and sos4 mutant roots, there are eight endodermal cells surrounding the stele, and eight cortical cells outside the endodermis (Fig. 4, E and F). There are also similar numbers of epidermal cells surrounding the cortex in the wild type and sos4 mutant (Fig. 4, E and F).

SOS4 Is Expressed in Root Hairs and Other Tip-Growing Cells

Analysis using SOS4 promoter-β-glucuronidase (GUS) in transgenic Arabidopsis revealed that SOS4 is ubiquitously expressed in roots, stem, and leaves (Shi et al., 2002). In this study, we performed detailed microscopic observations to determine whether SOS4 promoter-GUS is also expressed in root hairs and other hair-like cells. As shown in Figure 5, GUS expression was detected in the root hairs at the root-hypocotyl junction, although sos4 mutations do not have obvious effects on this type of root hair (Fig. 5A). As expected, GUS expression was also detected in the root hairs near the root tip (Fig. 5, B and C). Although the sos4 mutant is not defective in trichome development or pollen tube growth, GUS staining was detected in trichomes, pollens, and pollen tubes (Fig. 5, D–F). GUS was also strongly expressed in the papillar cells on the top of stigma (Fig. 5G). Nevertheless, our observations showed that the development of stigmatic papilla is not defective in sos4 mutants (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Detection of SOS4 promoter-GUS activity in root hair and other hair-like structures. A, GUS staining in the crown root hairs. B, Maturation zone of primary root, showing GUS expression in root hairs. C, Enlarged image of root hairs in B. D, Strong GUS staining in trichomes. E, Pollens. F, Germinated pollens. G, Stigma with strong GUS staining in papillar cells.

PN and PM, But Not PL, Can Partially Rescue the Root Hair Defect of sos4

Three natural, free forms of vitamin B6, PN, PL, and PM could be converted to the biologically active PLP. PL can be converted to PLP by PL kinase (SOS4). PN/PM can be converted to PNP/PMP by a presumably nonspecific PN/PM kinase, which then are turned into PLP by a PNP/PMP oxidase (McCormick and Chen, 1999). Because SOS4 encodes a PL kinase involved in the biosynthesis of active vitamin B6, in vitro application of vitamin B6 might rescue the mutant phenotypes (Shi et al., 2002). To test which form of vitamin B6 could rescue the sos4 root hair phenotype, feeding tests were carried out by adding 100 μm PN, PM, PL, or PLP dissolved in Murashige and Skoog nutrient solution directly onto growing root tips. Seeds were first germinated on Murashige and Skoog agar medium and 4-d-old seedlings were subjected to the vitamin B6 treatments. As shown in Figure 6, supplementation of PN, PM, or PL has no significant impact on the root hair growth of wild-type plants. However, 2 d after being treated with 100 μm PN or PM solution, sos4 roots exhibited growth of new root hairs, which is very distinct from the hairless part grown before treatment (Fig. 6, D and F). Quantitative measurements of root hair length further support that the PN and PM treatments did not significantly affect root hair elongation in wild-type seedlings, but induced root hair formation and elongation in sos4 mutant seedlings (Table I). No ectopic or multiple root hairs were observed in wild-type roots after the treatment with vitamins. These results suggest that the induction of root hair formation and elongation in sos4 mutant roots by PN and PM may due to biochemical complementation for the mutation in SOS4 gene rather than a general promotion of root hair initiation and elongation. PL did not rescue the root hair defect of sos4 mutant plants (Fig. 6H). PLP also failed to restore root hair growth in sos4 (not shown) because this compound is known to be incapable of passing through the cell membrane (Lam et al., 1992). These results are consistent with SOS4 being a PL kinase (Shi et al., 2002), and suggest that the root hair defect in sos4 is caused by a deficit in PLP.

Figure 6.

PN, PM, but not PL can partially rescue the root hair defect of sos4 mutant. A, C, E, and G, Wild type. B, D, F, and H, sos4-1. A and B, Primary root grown on Murashige and Skoog agar medium only. C and D, Primary root treated with 100 μm PN. E and F, Primary root treated with 100 μm PM. G and H, Primary root treated with 100 μm PL. Arrows show newly formed root hairs in sos4-1 mutant after treatments.

Table I.

Root hair length in response to vitamins and hormonesa

| Genotype | Root Hair Length

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | PN | PM | ACC | 2,4-D | |

| μm | |||||

| Wild type | 405 ± 11.3 | 392 ± 13.5 | 398 ± 10.4 | 830 ± 25.2 | 852 ± 34.4 |

| sos4-1 | 0 | 185 ± 25.2 | 226 ± 43.8 | 103 ± 4.2 | 335 ± 21.4 |

At least 50 root hairs were measured. ± Represents sd.

Ethylene and Auxin Induce Root Hair Growth in sos4

Both genetic and physiological studies have implicated ethylene and auxin in promoting root hair development (Schiefelbein, 2000). To examine the impact of these hormones on root hair development in sos4 mutants, we tested in vitro application of the ethylene precursor, ACC, and synthetic auxin 2,4-D. As expected, ACC promoted root hair growth in wild-type seedlings (Fig. 7A; Table I). Interestingly, ACC also induced root hair formation in sos4 mutant seedlings, although the length of the induced root hairs is still not as great as that of the wild type (Fig. 7B; Table I). The partial restoration of root hair growth in sos4 mutants by ACC indicates that SOS4 is possibly involved in ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis.

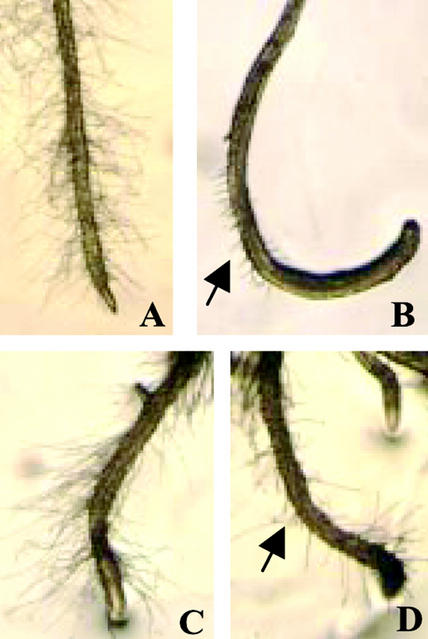

Figure 7.

ACC and 2,4-D promote root hair growth in sos4 mutant. A and C, Wild type. B and D, sos4-1 mutant. A and B, Primary root after ACC treatment. C and D, Primary root after 2,4-D treatment. Arrows show newly formed root hairs in sos4-1 mutant after treatments.

When 4-d-old seedlings were transferred to a medium containing 0.05 μm 2,4-D, the root hair growth of both wild-type and sos4 mutant seedlings was dramatically promoted (Fig. 7, C and D; Table I). The promotion of sos4 root hair growth by 2,4-D appeared to be greater than that by ACC (Fig. 7, B and D; Table I). This observation suggests that SOS4 also acts upstream of auxin in the control of root hair development.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported a defective root hair development phenotype of sos4 mutants. In Arabidopsis wild-type plants, the root epidermis is made of alternate columns of hair cells and hairless cells. Cell fate is determined by the relative location of epidermal cells with respect to the cortex cell walls. Epidermal cells will form hairs only if they are present over the radial walls separating adjacent cortical cells (Berger et al., 1998). Because there is a constant number of eight cortical cell files in the Arabidopsis primary root, the number of hair cell files is fixed to eight as well. After cell specification, hair cell initiation, and subsequent tip growth, visible root hairs can be seen from the end of the elongation zone up to the root-hypocotyl junction. Microscopic observations revealed that sos4 roots fail to form root hairs at the maturation zone and only have root hairs at the crown (root-hypocotyl junction; Fig. 2, B, D, and F). Although the cell files of sos4 primary roots are identical to those of wild-type roots (Fig. 4, E and F), sos4 root epidermis only shows a few occasional bulges (Fig. 4, A and B), indicating that the sos4 mutations not only arrest root hair tip growth, but also diminish root hair initiation. sos4 mutations have no effect on the location of root hair initiation sites (Fig. 4, C and D). The normal root hair development at the root-hypocotyl junction in sos4 mutants (Fig. 2F) suggests a distinct genetic control of root hair formation in this region.

The SOS4 gene was isolated previously by positional cloning and shown to function as a PL kinase that converts PL to the biologically active PLP (Shi et al., 2002). Besides rescuing the salt hypersensitive phenotype of sos4 mutant (Shi et al., 2002), PN and PM, but not PL, can also partially rescue the root hairless phenotype of sos4 (Fig. 6), further supporting that SOS4 functions as a PL kinase in Arabidopsis. Presumably due to salvage pathways of PLP biosynthesis, sos4 mutant plants are not completely deficient in PLP, as evidenced by the nonlethal nature of the sos4 null mutations (Shi et al., 2002).

PLP is one of the most versatile enzyme cofactors in nature. PLP-dependent enzymes play major roles in the metabolism of amino acids, and are found in various pathways ranging from the interconversion of α-amino acids to the biosynthesis of antibiotic compounds (Schneider et al., 2000). Among the superfamily of PLP-dependent enzymes, ACC synthase belongs to the α-family, shares a modest level of sequence similarity with other members of this family, and contains a PLP-binding site (Capitani et al., 1999). In plants, ACC synthase catalyzes the committed step in ethylene biosynthesis, the conversion of S-adenosyl-Met to ACC. ACC is converted to ethylene, which plays a critical role in root hair development. Therefore, the control of root hair formation by SOS4 is likely at least in part through the control of ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, which is supported by our finding that ACC could partially restore root hair formation in sos4 mutants.

Several enzymes involved in auxin biosynthesis may also be dependent on PLP. Evidence suggests that plants can synthesize IAA from l-Trp (Bartel, 1997). Trp synthase is one of the PLP-dependent enzymes (Schneider et al., 2000). The major pathway from l-Trp to IAA is thought to proceed via indole-3-pyruvic acid and indole-3-acetaldehyde. In this pathway, Trp aminotransferase, which converts l-Trp to indole-3-pyruvic acid, and indole-3-pyruvic acid decarboxylase, which catalyzes the formation of indole-3-acetaldehyde, are also presumably PLP-dependent enzymes. Previous studies have shown that treatment of Arabidopsis wild-type roots with 2,4-D promotes root hair elongation (Pitts et al., 1998). The increased root hair length by 2,4-D treatment in wild-type plants is possibly due to the induction of ethylene biosynthesis in roots (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1996). Our results show that 2,4-D induces root hair formation in sos4 mutant plants and that the root hair length induced by 2,4-D appears to be much greater than that induced by ACC. This suggests that sos4 mutations disrupt root hair development mainly by affecting the level of auxin in root epidermal cells.

The sos4 mutant shows a very similar root hairless phenotype as the rhd6 mutant. rhd6 also has normal root hair development at the root-hypocotyl junction but nearly no root hair formation at the elongated zone of mature roots (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994). In vitro application of auxin and ethylene also was shown to be able to rescue the rhd6 mutant phenotype (Masucci and Schiefelbein, 1994). The RHD6 gene was mapped to chromosome 1 of Arabidopsis (Parker et al., 2000), indicating that it encodes a protein distinct from SOS4. The phenotypic similarities suggest that SOS4 and RHD6 may function in the same pathway controlling root hair development.

Plant root hairs are thought to play critical roles in the anchorage, nutrient uptake, and interaction with microbes (Peterson and Farquhar, 1996). The tube-like growth pattern of root hairs increases the root surface area that contacts with soil to aid nutrient ion uptake. Although the normal vegetative growth in some root hair-defective mutants (Schiefelbein and Somerville, 1990) indicates that root hairs are not essential for growth, the involvement of root hairs in the uptake of most major and micronutrients has been documented (for review, see Gilroy and Jones, 2000). As the most abundant cellular cation, potassium can be accumulated from soils to a cytoplasmic level exceeding 100 mm. The preferential expression of some K+ channels in root hair cells suggests that root hairs are involved in potassium uptake (Downey et al., 2000; Hartje et al., 2000). The fact that sos4 mutant roots accumulated less potassium than the wild-type roots (Shi et al., 2002) supports the notion that root hairs play some role in K+ uptake.

The precise mechanism of SOS4 function in controlling root hair development requires further investigation. The effect of sos4 mutations on the levels of PLP and its intermediates in various plant tissues needs to be determined. Quantitative measurements of auxin and ethylene contents in sos4 mutant plants could provide direct evidence to support our hypothesis that the sos4 mutations disrupt root hair development by reducing auxin and ethylene biosynthesis in some root cells. Generation and characterization of double or triple mutants between sos4 and other root hair mutants would help to better position SOS4 in the genetic network controlling root hair development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The isolation of sos4 mutants and SOS4 gene cloning have been described recently (Shi et al., 2002). Mutant and wild-type Arabidopsis (ecotype Columbia) seeds were surface sterilized and rinsed with sterile water. The seeds were then suspended in sterile 0.3% (w/v) low-melting-point agarose. After being treated at 4°C for 3 d, the seeds were sown in rows onto Murashige and Skoog nutrients agar media as previously described (Wu et al., 1996). The plates were placed vertically in a growth chamber at 22°C, with a daily cycle of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark.

Analysis of Root Morphology

Photographs of roots grown vertically on agar surface as described above were taken under a stereomicroscope. For SEM, the roots of 7-d-old seedlings were fixed in situ in the agar plates by using 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in Murashige and Skoog solution and post-fixed with 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide in water. After dehydration and critical point drying, the samples were attached to stubs, coated with gold, and examined under SEM. For thin cross section, the materials were infiltrated with LR White resin after fixation and dehydration. Sections (1.0 μm thick) were collected and examined under a light microscope. Seven-day-old seedlings were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution, washed with PBS, and stained with 0.01% (w/v) fluorescent brightener 28 (Sigma, St. Louis) in PBS for 1 min. Stained materials were washed with PBS, placed onto a glass microscope slide under a coverslip, and visualized using a 1024 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) attached to a Optiphot 2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo).

Complementation Test

The construction of binary SOS4 gene constructs for complementation and the plant transformation were described previously (Shi et al., 2002). Two types of SOS4 cDNA, designated as ScDNA (short cDNA) and LcDNA (long cDNA), were amplified by reverse transcriptase-PCR and cloned into binary vector for complementation tests (Shi et al., 2002). The two cDNAs arise from alternative splicing and differ in the first exon; the LcDNA includes approximately 100 bp that is spliced out in the ScDNA (Shi et al., 2002). At least 10 independent transgenic lines in the T2 generation for each construct were examined for the complementation of root hair phenotype.

GUS Staining

An approximately 1.9-kb promoter region of the SOS4 gene was cloned into binary vector pCAMBIA 1391Z, resulting in a transcriptional fusion of SOS4 promoter and the GUS coding region (Shi et al., 2002). T2 transgenic seedlings grown vertically on agar surface were subjected to GUS staining to visualize the GUS expression in root hairs and leaf trichomes. Hygromycin-resistant T2 transgenic plants were transferred to soil and grown to adult plants for GUS staining of the stigma and pollens. Pollens were germinated in a pollen germination medium containing 5 μm CaCl2, 5 μm Ca(NO3)2, 1 mm MgSO4, 0.01% (w/v) H3BO3, and 18% (w/v) Suc, pH 6.5, and the pollen tubes were stained to visualize GUS expression.

Vitamin B6 and Hormone Treatments

Seedlings were grown in vertical agar plates as described above for 4 d. For vitamin treatments, 100 μm PN, PL, pyridoxamine, or PLP in Murashige and Skoog solution was directly added to the root tip region. The plates were then placed horizontally and the seedlings were cultured for 2 to 4 d after adding the solution. For hormone treatment, 4-d-old seedlings were transferred to Murashige and Skoog agar medium containing 5 μm ACC or 0.05 μm 2,4-D. The plates were placed vertically and seedlings were grown for 4 more d before their photographs were taken. Root hair length on newly grown root parts was measured under a dissecting microscope using a micrometer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Ms. Becky Stevenson for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01GM59138 to J.-K.Z.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.001982.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bartel B. Auxin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:51–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N, Ringli C, Keller B. The chimeric leucine-rich repeat/extensin cell wall protein LRX1 is required for root hair morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1128–1139. doi: 10.1101/gad.200201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Hung CY, Dolan L, Schiefelbein J. Control of cell division in the root epidermis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev Biol. 1998;194:235–245. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capitani G, Hohenester E, Feng L, Storici P, Kirsch JF, Jansonius JN. Structure of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the plant hormone ethylene. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:745–756. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristina M, Sessa G, Dolan L, Linstead P, Baima S, Ruberti I, Morelli G. The Arabidopsis Athb-10 (GLABRA2) is an HD-Zip protein required for regulation of root hair development. Plant J. 1996;10:393–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10030393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey P, Szabo I, Ivashikina N, Negro A, Guzzo F, Ache P, Hedrich R, Terzi M, Schiavo FL. KDC1, a novel carrot root hair K+ channel. Cloning, characterization, and expression in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39420–39426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favery B, Ryan E, Foreman J, Linstead P, Boudonck K, Steer M, Shaw P, Dolan L. KOJAK encodes a cellulose synthase-like protein required for root hair cell morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:79–89. doi: 10.1101/gad.188801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galway ME, Masucci JD, Lloyd AM, Walbot V, Davis RW, Schiefelbein JW. The TTG gene is required to specify epidermal cell fate and cell patterning in the Arabidopsis root. Dev Biol. 1994;166:740–754. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy S, Jones DL. Through form to function: root hair development and nutrient uptake. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:56–60. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartje S, Zimmermann S, Klonus D, Mueller-Roeber B. Functional characterization of LKT1, a K+ uptake channel from tomato root hairs, and comparison with the closely related potato inwardly rectifying K+ channel SKT1 after expression in Xenopus oocytes. Planta. 2000;210:723–731. doi: 10.1007/s004250050673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung CY, Lin Y, Zhang M, Pollock S, Marks MD, Schiefelbein J. A common position-dependent mechanism controls cell-type patterning and GLABRA2 regulation in the root and hypocotyl epidermis of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:73–84. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieber JJ, Rothenberg M, Roman G, Feldmann KA, Ecker JR. CTR1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the raf family of protein kinases. Cell. 1993;72:427–441. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HM, Tancula E, Dempsey WB, Winkler ME. Suppression of insertions in the complex pdxJ operon of Escherichia coli K-12 by lon and other mutations. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1554–1567. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1554-1567.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Schiefelbein J. WEREWOLF, a MYB-related protein in Arabidopsis, is a position-dependent regulator of epidermal cell patterning. Cell. 1999;99:473–483. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyser HM, Pickett FB, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. Mutations in the AXR3 gene of Arabidopsis result in altered auxin response including ectopic expression from the SAUR-AC1 promoter. Plant J. 1996;10:403–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10030403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci JD, Schiefelbein JW. The rhd6 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana alters root hair initiation through an auxin and ethylene associated process. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1335–1346. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masucci JD, Schiefelbein JW. Hormones act downstream of TTG and GL2 to promote root hair outgrowth during epidermis development in the Arabidopsis root. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1505–1517. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.9.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DB, Chen H. Update on interconversions of vitamin B-6 with its coenzyme. J Nutr. 1999;129:325–327. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk AJ, Bischoff F, Rajendrakumar CS, Friml J, Braun M, Gilroy S, Palme K. Arabidopsis thaliana Rop GTPases are localized to tips of root hairs and control polar growth. EMBO J. 2001;20:2779–2788. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Cavell AC, Dolan L, Robert K, Grierson CS. Genetic interactions during root hair morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1961–1974. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RL, Farquhar ML. Root hairs: specialized tubular cells extending root surfaces. Bot Rev. 1996;62:2–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RJ, Cernac A, Estelle M. Auxin and ethylene promote root hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 1998;16:553–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rerie WG, Feldmann KA, Marks MD. The GLABRA2 gene encodes a homeodomain protein required for normal trichome development in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1388–1399. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigas S, Debrosses G, Haralampidis K, Vicente-Agullo F, Feldmann K, Grabov A, Dolan L, Hatzopoulos P. Trh1 encodes a potassium transporter required for tip growth in a Arabidopsis root hairs. Plant Cell. 2001;13:139–151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein JW. Constructing a plant cell. The genetic control of root hair development. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1525–1531. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefelbein JW, Somerville C. Genetic control of root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 1990;2:235–243. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G, Käck H, Lindqvist Y. The manifold of vitamin B6 dependent enzymes. Structure. 2000;8:R1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K, Wells B, Dolan L, Roberts K. Structural and genetic analysis of epidermal cell differentiation in Arabidopsis primary roots. Development. 1997;124:1789–1798. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepf E. Cellular polarity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Xiong L, Stevenson B, Lu T, Zhu J-K. The Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive 4 mutants uncover a critical role for vitamin B6 in plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell. 2002;14:575–588. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto M, Roberts K, Dolan L. Ethylene is a positive regulator of root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1995;8:943–948. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8060943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Tachibana T, Shimura Y, Okada K. Epidermal cell differentiation in Arabidopsis determined by a Myb homolog, CPC. Science. 1997;277:1113–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, Davison PA, Bolognesi-Winfield AC, James CM, Srinivasan N, Blundell TL, Esch JJ, Marks MD, Gray JC. The TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 locus, which regulates trichome differentiation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, encodes a WD40 repeat protein. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1337–1350. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Cnops G, Vanderhaeghen R, De Block S, Van Montagu M, Van Lijsebettens M. AtCSLD3, a cellulose synthase-like gene important for root hair growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:575–586. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Lockwood SK, Hoeltzel MF, Schiefelbein JW. The ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE3 gene encodes an evolutionarily conserved protein with GTP-binding motifs and is required for regulated cell enlargement in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:799–811. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AK, Pickett FB, Turner JC, Estelle M. A dominant mutation in Arabidopsis confers resistance to auxin, ethylene and abscisic acid. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:377–383. doi: 10.1007/BF00633843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Ding L, Zhu J-K. SOS1, a genetic locus essential for salt tolerance and potassium acquisition. Plant Cell. 1996;8:617–627. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZL, Yang Z. The Rrop GTPase switch turns on polar growth in pollen. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:298–303. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01654-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]