Abstract

The profile of opioid and cannabinoid receptors in neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) has been studied using the whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique.

Experiments with selective agonists and antagonists of opioid, ORL and cannabinoid receptors indicated that μ-opioid, κ-opioid, ORL-1 and CB1, but not δ-opioid, receptors inhibit VDCCs in NTS.

Application of [D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO; μ-opioid receptor agonist), Orphanin FQ (ORL-1 receptor agonist) and WIN55,122 (CB1 receptor agonist) caused inhibition of IBa in a concentration-dependent manner, with IC50's of 390 nM, 220 nM and 2.2 μM, respectively.

Intracellular dialysis of the Gi-protein antibody attenuated DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,122-induced inhibition of IBa.

Both pretreatment with adenylate cyclase inhibitor and intracellular dialysis of the protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor attenuated WIN55,122-induced inhibition of IBa but not DAMGO- and Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition.

Mainly N- and P/Q-type VDCCs were inhibited by both DAMGO and Orphanin FQ, while L-type VDCCs were inhibited by WIN55,122.

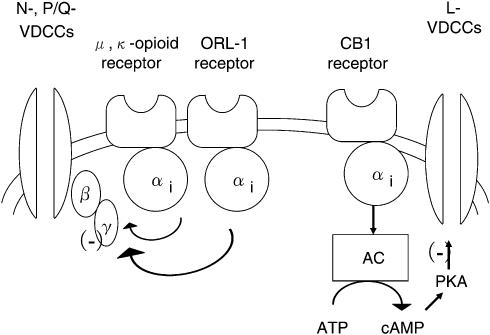

These results suggest that μ- and κ-opioid receptors and ORL-1 receptor inhibit N- and P/Q-type VDCCs via Gαi-protein βγ subunits, whereas CB1 receptors inhibit L-type VDCCs via Gαi-proteins involving PKA in NTS.

Keywords: Nucleus tractus solitarius, calcium channel currents, opioid peptides, cannabinoid, patch-clamp techniques

Introduction

Endogenous opioid peptides and their analogs produce many effects, such as analgesia, modulation of pain transmission, inhibition of diarrhea, respiratory depression and catalepsy, on the nervous system by interacting with a widely distributed receptor system. At a cellular level, these effects result from modulation of ionic channels. Opioid receptors are G-protein coupled and have been classified into three major subtypes, namely μ-, κ- and δ-opioid receptors (Uhl et al., 1994). The endogenous ligands for these subtypes of opioid receptors are endomorphins (Monory et al., 2000), enkephalins and dynorphins (Sapru et al., 1987), respectively.

After successful cloning of cDNAs encoding the classic opioid receptors, a novel opioid-related receptor was cloned by several groups (Henderson & McKnight, 1997). This new receptor is named opioid-receptor-like-1 (ORL-1) receptor. In searching for a natural ligand that interacts with the ORL-1 receptor, Meunier et al. (1995) and Reinscheid et al. (1996) isolated and identified a biologically active heptadecapeptide from rat brain that was named nociceptin (Meunier et al., 1995) and Orphanin FQ (Reinscheid et al., 1996) (hereafter N/OFQ). Zhang & Yu (1995) have identified dynorphin A as a potential ligand for the ORL-1 receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes. This receptor also shares a high sequence homology with opioid receptors (Bunzow et al., 1994).

Cannabinoids, the active constituents of marijuana, have a broad range of potential medical benefits, including analgesic, antiemetic and anticonvulsive effects (Hollister, 1984; Howlett, 1995). The brain cannabinoid (CB1) receptor is a member of G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily (Matsuda et al., 1990). Many studies demonstrate the existence of bi-directional interactions between the endogenous cannabinoid and opioid systems (Manzanares et al., 1999; Maldonado, 2003). Accordingly, the endogenous opioid system has been reported to participate in several pharmacological actions induced by cannabinoid, such as antinociception, addictive properties and anxiolytic-like effects (Pertwee, 2001; Berrendero & Maldonado, 2002; Maldonado & Rodríguez de Fonseca, 2002).

The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) is known to play a major role in the regulation of cardiovascular, respiratory, gustatory, hepatic and swallowing functions (Lawrence & Jarrott, 1996; Jean, 2001). The NTS appears not to be a simple ‘relay' nucleus, rather it performs complex integration of information from multiple synaptic inputs of both peripheral and central origins (Paton & Kasparov, 1999). Several studies demonstrated that administration of opioid peptides, N/OFQ and cannabinoid into the NTS area resulted in increased feeding (Kotz et al., 1997), inhibition of gastric secretions (Burks et al., 1987; Del Tacca et al., 1987), respiratory depression (Padley et al., 2003; Pfitzer et al., 2004) and elevated blood pressure and heart rate (Mao & Wang, 2000).

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) serve as crucial mediators of membrane excitability and Ca2+-dependent functions, such as neurotransmitter release, enzyme activity and gene expression. The modulation of VDCCs is believed to be an important means of regulating Ca2+ influx and thus has a direct influence on many Ca2+-dependent processes. Modulation of VDCC current (ICa) by opioid has been described previously in various types of cells. Rhim et al. (1996) demonstrated that in NTS μ-opioid receptor inhibits VDCCs. In addition, it has been reported that both N/OFQ and cannabinoid modulate VDCCs in other cells (Mackie & Hille, 1992; Twitchell et al., 1997). However, the mechanism of opioid and cannabinoid effects on VDCCs in NTS has been extensively studied, but remains unclear and even controversial. Consequently, it is the purpose of this study to investigate the effects of opioids and cannnabinoids on ICa in NTS.

Methods

Cell preparation

Experiments were conducted according to the international guidelines on the use of animals for experimentation. Young Wistar rats (7–18 days old) were decapitated and their brains were quickly removed and submerged in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 of the following composition (in mM): 126 NaCl, 26.2 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 3 KCl, 1.5 MgSO4, 1.5 CaCl2 and 30 glucose; pH 7.4. Thin transverse slices from brainstems, 400 μm in thickness, were prepared by a tissue slicer (DTK-1000; Dosaka EM Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan). After being sectioned, 3–5 slices obtained from a single brain were transferred to a holding chamber and stored in oxygenated aCSF at room temperature for at least 40 min before use. Slices were then transferred to a conical tube containing gently bubbled aCSF at 36°C, to which 1.8 U ml−1 dispase (grade I; 0.75 ml slice−1) was added. After 60 min incubation, slices were rinsed with enzyme-free aCSF. Under a dissecting microscope, the NTS region was micropunched and placed on a poly-L-lysine-coated coverslip. The cells were then dissociated by trituration using progressively smaller-diameter pipettes and allowed to settle on a coverslip for 20 min.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Voltage-clamp recordings were conducted using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981). Fabricated recording pipettes (2–3 MΩ) were filled with the internal solution of the following composition (in mM): 100 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 BAPTA, 3.6 MgATP, 14 Tris2phosphocreatine (CP), 0.1 GTP and 50 U ml−1 creatine phosphokinase (CPK). The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The inclusion of CP and CPK effectively reduced ‘rundown' of current. After the formation of a giga seal, in order to record ICa carried by Ba2+ (IBa), the external solution was replaced from Krebs solution to a solution containing the following (in mM): 151 tetraethylammonium (TEA) chloride, 5 BaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES and 10 glucose. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with TEA-OH. Command voltage protocols were generated with a computer software pCLAMP version 8 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.) and transformed to an analogue signal using a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, U.S.A.). DigiData 1200 interface was used to record and digitize current. The command pulses were applied to cells through an L/M-EPC7 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). The currents were recorded with the amplifier and a computer software pCLAMP 8 acquisition system. Access resistance (<15 Mω) was determined by transient responses to voltage commands. Access resistance compensation was not used. To ascertain that no major changes in the access resistance had occurred during the recordings, a 5-mV, 10-ms pulse was used before IBa was evoked. Initial input resistances were in the range of 500 MΩ to 1.2 GΩ. Series resistance was estimated by cancellation of the capacitance-charging current transient after patch rupture. In most case, series resistance compensation of 80–90% was obtained without inducing significant noise or oscillation, resulting in final series resistances ranging from 0.1 to 1.2 MΩ. No data were included in the analysis where series resistance resulted in a 5 mV or greater error in voltage commands.

Materials

[D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO), Orphanin FQ, WIN55,122, U69593, [D-Pen2,5]-enkephalin (DPDPE), naloxone, [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2, PD98,059 and nifedipine (Nif) were purchased from Sigma (Tokyo, Japan). AM281 was purchased from Tocris (Avonmouth, U.K.). Anti-Gαi antibodies, anti-Gαq/11 antibodies and anti-Gαs antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). All antibodies were from rabbits immunized with a synthetic peptide corresponding to the COOH-terminal sequence of the human Gαi, Gαq/11 and Gαs subunits. SQ22536 and PKI(5–24) were purchased from Biomol Research Laboratories (Plymouth, PA, U.S.A.). 2-[1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide (GF109203X) and LY294002 were purchased from Calbiochem. ω-Conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTx GVIA) and ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-Aga IVA) were purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan). Most drugs were dissolved in distilled water. U69593 was dissolved in ethanol. WIN55,122, PD98,059, AM281, GF109203X and Nif were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 mM as a stock solution. The final concentration of DMSO and ethanol was <0.01%, which had no effect on the IBa.

Analysis and statistics

All data analyses were performed using pCLAMP 8.0 acquisition system. Values in text and figures are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was made by Student's t-test for comparisons between pairs of groups and by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's test. Probability (P) values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa

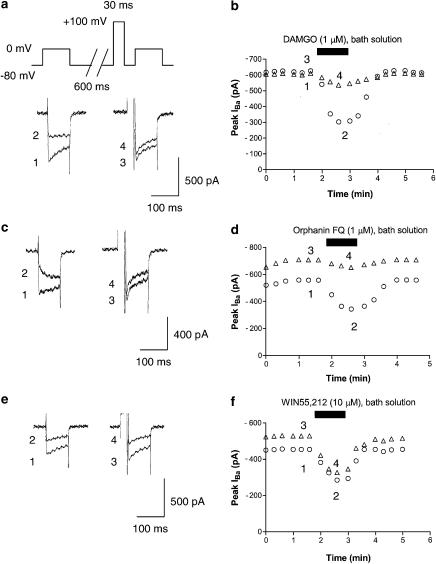

Representative examples of superimposed IBa traces in the absence and presence of 1 μM DAMGO (μ-opioid receptor agonist), 1 μM Orphanin FQ (ORL-1 receptor agonist) and 10 μM WIN55,212 (CB1 receptor agonist) are shown in Figure 1. IBa was evoked every 20 s with a 100-ms depolarizing voltage step to 0 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. The average IBa value (around 620 pA) was slightly, but nonsignificantly, smaller than the value that has been previously demonstrated by Rhim & Miller (around 1 nA, 1994).

Figure 1.

Opioid-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa. (a) Typical superimposed IBa traces recorded using a double-pulse voltage protocol at the times indicated in the time-course graph b. Paired IBa were evoked from a holding potential of −80 mV by a 100-ms voltage step to 0 mV at 20-s intervals. An intervening strong depolarizing prepulse (100 mV, 30 ms) ended 5 ms prior to the second IBa activation. (b) Typical time course of DAMGO-induced IBa inhibition. The opened circle and triangles in the graph indicate IBa without prepulse and IBa with prepulse, respectively. DAMGO (1 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. (c) Typical superimposed IBa traces recorded using a double-pulse voltage protocol at the times indicated in the time course graph d. (d) Typical time course of Orphanin FQ-induced IBa inhibition. Orphanin FQ (1 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. (e) Typical superimposed IBa traces recorded using a double-pulse voltage protocol at the times indicated in the time course graph f. (f) The typical time course of WIN55,212-induced IBa inhibition. WIN55,212 (10 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar.

As shown in Figure 1, application of DAMGO (in 106 of 142 neurons), Orphanin FQ (in 109 of 151 neurons) and WIN55,212 (in 83 of 131 neurons) rapidly and reversibly inhibits IBa. Application of 1 μM U69593 (κ-opioid receptor agonist) also inhibits IBa (in 99 of 132 neurons, data not shown). In contrast, application of 1 μM DPDPE (δ opioid receptor agonist) did not modulate IBa (n=31).

To investigate the voltage dependency of inhibition of IBa by opioid and cannabinoid, we used a double-pulse voltage protocol as shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, the application of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse attenuated DAMGO- and Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa. In addition, the application of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse also attenuated 1 μM U69593-induced inhibition of IBa (data not shown). In contrast, WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa was not attenuated by prepulse.

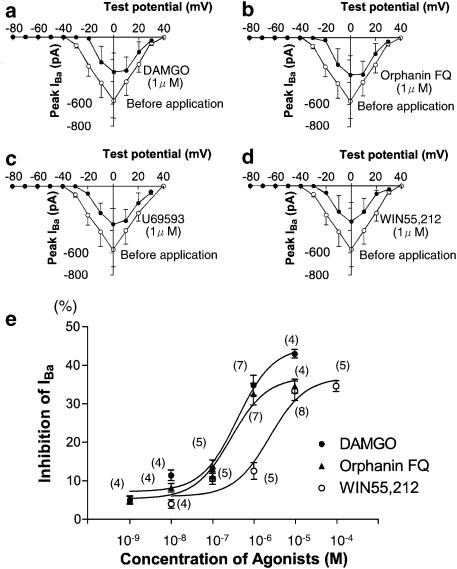

The current–voltage relationships for IBa in the absence and presence of 1 μM DAMGO, 1 μM Orphanin FQ, 1 μM U69593 and 10 μM WIN55,212 are shown in Figures 2a–d. From a holding potential of −80 mV, the IBa was activated after −30 mV with a peak current amplitude at 0 mV. As shown in Figures 2a–d, DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and U69593-induced inhibition resulted in a shift in the voltage dependence of the IBa to more positive potentials. In contrast, WIN55,212 did not change the shape of current–voltage relationship; that is, the peak potential for IBa was not altered.

Figure 2.

Current–voltage relations and dose dependency of opioid-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa. (a) Current–voltage relations of IBa evoked by a series of voltage steps from a holding potential of −80 mV to test pulses between −80 and +40 mV in +10 mV increments in the absence (opened points) and presence (filled points) of DAMGO (1 μM). (b) Current–voltage relations of IBa in the absence (opened points) and presence (filled points) of Orphanin FQ (1 μM). (c) Current–voltage relations of IBa in the absence (opened points) and presence (filled points) of U69593 (1 μM). (d) Current–voltage relations of IBa in the absence (opened points) and presence (filled points) of WIN55,212 (10 μM). Values of IBa are the averages of five neurons each. (e) Concentration–response curves for IBa inhibition induced by DAMGO (•), Orphanin FQ (▴) and WIN55,212 (○). The currents were elicited as in Figure 1. The inhibition (%) was normalized to that induced by each agonist at a maximal concentration. The curve was obtained from fitting to a single-site binding isotherm with least-squares nonlinear regression. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested.

The dose–response relation in the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa is shown in Figure 2e. For the generation of the concentration–response curve, opioid and cannabinoid concentrations were applied randomly, and not all concentrations in a single neuron were tested. Figure 2e shows that progressive increases in opioid and cannabinoid concentration resulted in progressively greater inhibition of IBa.

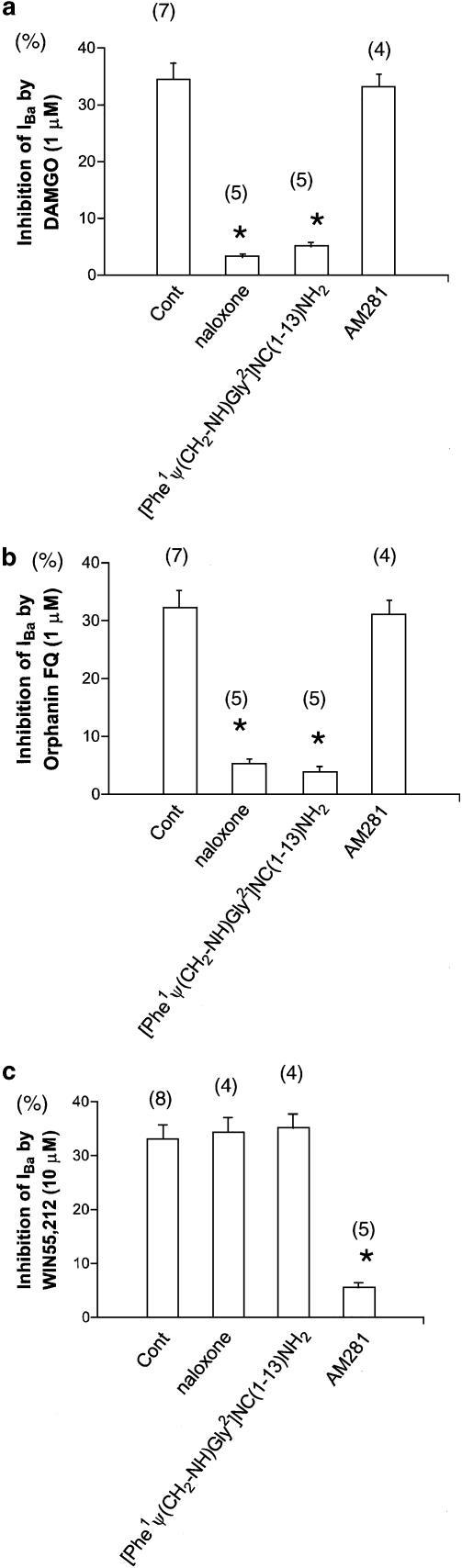

Effects of various antagonists in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa

In the next series of experiments, we analyzed the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in neurons treated with specific antagonists. In this experiment, specific antagonists were applied prior to the opioid or cannabinoid. Treatment with opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (1 μM for 3 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration) attenuated the DAMGO-induced inhibition of IBa. Treatment with ORL-1 receptor antagonist [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 (10 μM for 3 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration) also attenuated the DAMGO-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, treatment with CB1 receptor antagonist AM281 (10 μM for 3 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration) did not attenuate the DAMGO-induced inhibition of IBa.

Treatment with naloxone attenuated the Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa. Treatment with [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 also attenuated the Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, treatment with AM281 did not attenuate the Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa.

Treatment with naloxone did not attenuate the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa. Treatment with [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 also did not attenuate the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, treatment with AM281 attenuated the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Antagonist effects of opioid-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa. (a) IBa inhibition by 1 μM DAMGO in control (untreated neurons), after naloxone (opioid receptor antagonist), after [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 (ORL-1 receptor antagonist) and after AM281 (CB1 receptor antagonist). (b) IBa inhibition by 1 μM Orphanin FQ in control (untreated neurons), after naloxone, after [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 and after AM281. (c) IBa inhibition by 10 μM WIN55,212 in control (untreated neurons), after naloxone, after [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2 and after AM281. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested. *P<0.05 compared with control, ANOVA.

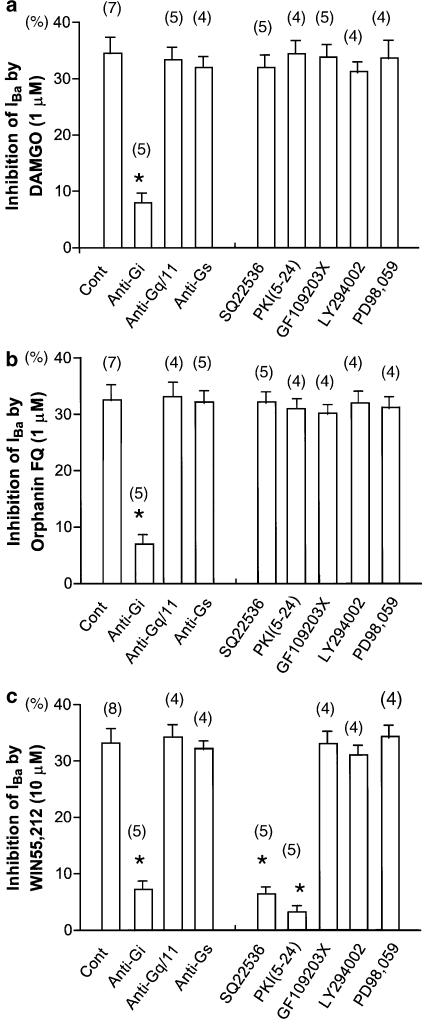

Characterization of G-protein subtypes in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa

The G-protein comprises heterotrimeric molecules with α, β and γ subunits. The α subunit can be classified into families, depending on whether they are targets for pertussis toxin (PTX) (Gi/o), cholera toxin (Gs), or neither. To characterize the G-protein subtypes in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, specific antibodies raised against the Gαi-, Gαq/11- and Gαs-protein were used. Experiments were performed using a solution in a pipette containing each G-protein antibody. In these experiments, the G-protein antibody (1 : 50 dilution; the final concentration was approximately 0.5 mg ml−1) was dissolved in the internal solution. The tip of the recording pipette was filled with the standard internal solution, and the pipette was then backfilled with solution which containing the G-protein antibody. In order to obtain the effect of antibody, opioid or cannabinoid was applied 7 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration.

As shown in Figure 4, intracellular dialysis of the Gαi-protein antibody attenuated the DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, intracellular dialysis of Gαq/11- and Gαs-protein antibodies did not attenuate the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa. Using the same protocol, we have demonstrated that intracellular dialysis of the Gαq/11-protein antibody (0.5 mg ml−1) attenuated metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonist-induced facilitation of VDCCs (Endoh, 2004). Thus, it can be considered that these methods are suitable for the questions posed. These results suggest that the Gαi-proteins are involved in the DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa in NTS, but Gαq/11- and Gαs-proteins are not.

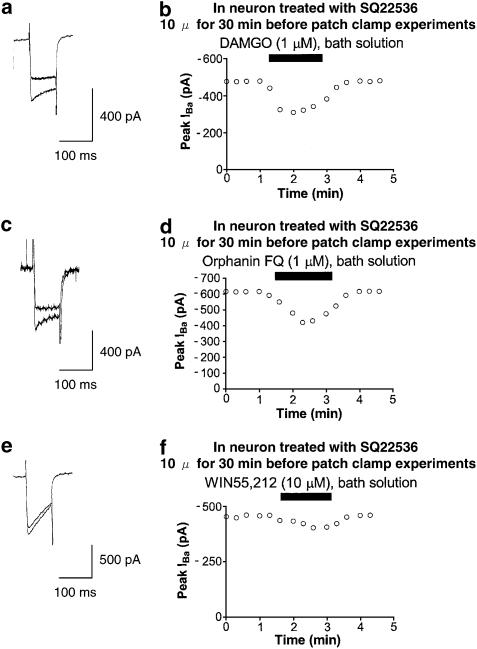

Figure 4.

Opioid-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa in neuron treated with adenylate cyclase inhibitor. (a) Typical superimposed IBa traces at the times indicated in the time-course graph b. (b) Typical time course of DAMGO-induced IBa inhibition. DAMGO (1 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. (c) Typical superimposed IBa traces at the times indicated in the time-course graph d. (d) Typical time course of Orphanin FQ-induced IBa inhibition. Orphanin FQ (1 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. (e) Typical superimposed IBa traces at the times indicated in the time course graph f. (f) Typical time course of WIN55,212-induced IBa inhibition. WIN55,212 (10 μM) was bath-applied during the time indicated by the filled bar.

Characterization of second messengers in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa

To investigate which second messengers contribute to opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of IBa in neurons treated with specific activators and inhibitors of the second messenger kinases were examined.

To evaluate the possible contribution of adenylate cyclase to the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in neurons treated with SQ22536 (a selective adenylate cyclase inhibitor) were investigated. Treatment with SQ22536 (10 μM for 30 min before patch-clamp experiments) attenuated the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, treatment with SQ22536 did not attenuate the DAMGO- and Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 4).

To evaluate the possible contribution of protein kinase A (PKA) to the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in the presence of PKI(5–24) (a selective PKA inhibitor) in the recording pipette were investigated. Intracellular application of PKI(5–24) (20 μM for 7 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration) attenuated the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa. In contrast, intracellular application of PKI(5–24) did not attenuate the DAMGO- and Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Summary of opioid-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa under various conditions. (a) IBa inhibition by 1 μM DAMGO in control (untreated neurons), intracellular dialysis with anti-Gi antibody, intracellular dialysis with anti-Gq/11 antibody, intracellular dialysis with anti-Gs antibody, after SQ22536 (an adenylate cyclase inhibitor), intracellular dialysis with PKI(5–24) (a PKA inhibitor), after GF109203X (a PKC inhibitor), after LY294002 (a PI3K inhibitor) and after PD98,059 (a MAPK inhibitor). (b) IBa inhibition by 1 μM Orphanin FQ in control (untreated neurons) and other conditions. (c) IBa inhibition by 10 μM WIN55,212 in control (untreated neurons) and other conditions. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested. *P<0.05 compared with control.

To evaluate the possible contribution of protein kinase C (PKC) to the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in neurons treated with GF109203X (a selective PKC inhibitor) were investigated. Treatment with GF109203X (10 μM for 30 min before patch-clamp experiments) did not attenuate the DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 5). Using the same protocol, we have demonstrated that pretreatment with GF109203X (10 μM for 30 min) attenuated mGluR agonist-induced facilitation of VDCCs (Endoh, 2004). Thus, it can be considered that these methods are suitable for the questions posed.

To evaluate the possible contribution of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) to the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in neurons treated with LY294002 (a selective PI3K inhibitor) were investigated. Treatment with LY294002 (10 μM for 10 min before patch-clamp experiments) did not attenuate the DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 5).

To evaluate the possible contribution of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) to the opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa, the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on IBa in neurons treated with PD98,059 (a selective MAPK inhibitor) were investigated. Treatment with PD98,059 (10 μM for 2 min after assuming the whole-cell configuration) did not attenuate the DAMGO-, Orphanin FQ- and WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa (Figure 5). Using the same protocol, we have demonstrated that pretreatment with PD98,059 (10 μM for 2 min) attenuated angiotensin II-induced facilitation of VDCCs (Endoh, 2005). Thus, it can be considered that these methods are suitable for the questions posed.

These results indicate that the PKA are involved in the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of IBa in NTS.

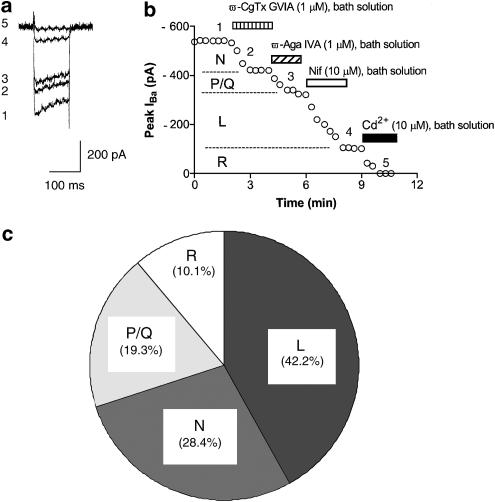

Characterization of VDCC subtypes in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of IBa

Several studies have defined pharmacological distinct high voltage-activated (HVA) VDCCs on neuronal cell bodies, such as L-, N-, P-, Q- and R-type VDCCs. In this study, specific VDCC blockers were used to isolate each VDCC's current component. Typical examples of sequential application of each selective blocker on IBa are shown in Figure 6. ω-CgTx GVIA, ω-Aga IVA and Nif block N-, P/Q- and L-type VDCCs, respectively. In this study, the mean percentages of IBa-L, IBa-N, IBa-P/Q and IBa-R of total IBa are 42.2±3.8, 28.4±3.4, 19.3±3.2 and 10.1±1.4%, respectively (n=9). These data are quite similar to the previous data reported by Ishibashi et al. (1995). It has been demonstrated in NTS that the mean percentages of ICa-L, ICa-N, ICa-P/Q and ICa-R of total ICa were 35.7, 28.7, 19.3 and 16.0%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Pharmacological characterization of four IBa components by sequential application of each VDCC blocker. (a) Typical superimposed IBa traces at the times indicated in the time-course graph b. (b) Typical time course of sequential application of each selective VDCC blocker on IBa. ω-CgTx GVIA, ω-Aga IVA, Nif and Cd2+ were bath applied during the time indicated by the filled bar. ω-CgTx GVIA, ω-Aga IVA, Nif and Cd2+ were bath-applied during the time indicated by each bar. (c) Summary of the distribution of VDCC subtypes.

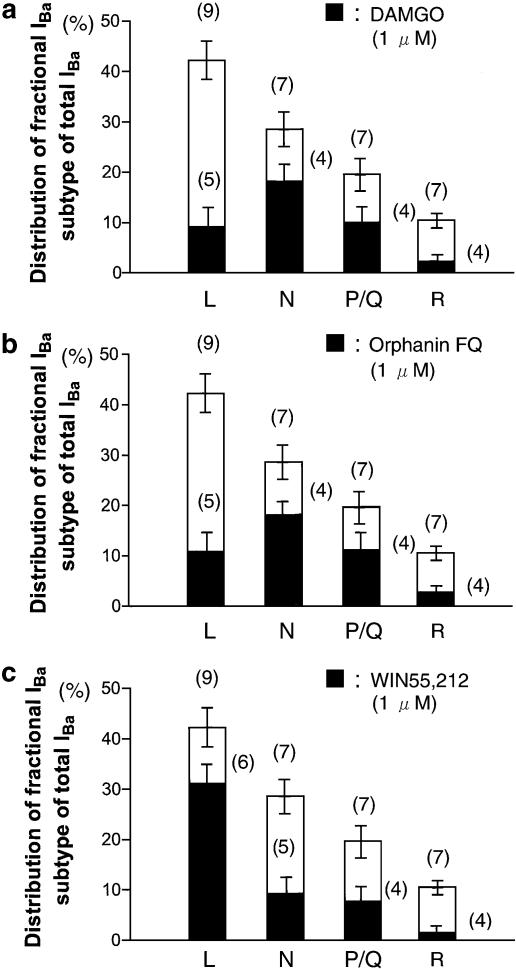

Therefore, it was investigated as to which types of the VDCCs were inhibited by opioid and cannabinoid. The effect of opioid and cannabinoid on the IBa-L was investigated using a neuron treated with ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM) and ω-Aga IVA (1 μM). The effect of opioid and cannabinoid on the IBa-N was investigated using a neuron treated with Nif (10 μM) and ω-Aga IVA (1 μM). The effect of opioid and cannabinoid on the IBa-P/Q was investigated using a neuron treated with Nif (10 μM) and ω-CgTx GVIA (1 μM). The effect of opioid and cannabinoid on the IBa-R was investigated using a neuron treated with all VDCC blockers.

Each of the IBa components and the percentage of the inhibition by DAMGO, Orphanin FQ and WIN55,212 are summarized in Figure 7. In this figure, contribution of the total current represents the mean percentages of IBa-L, IBa-N, IBa-P/Q and IBa-R of total IBa from Figure 6. In the case of DAMGO and Orphanin FQ, only the inhibition of IBa-N and IBa-P/Q was significant. In contrast, WIN55,212 mainly inhibited IBa-L. Results shown in Figure 7 demonstrate that DAMGO and Orphanin FQ inhibited IBa-N and IBa-P/Q, whereas WIN55,212 inhibited IBa-L in NTS neurons (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Opioid agonist-, Orphanin FQ- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of distinct IBa. (a) Fractional components of L-, N-, P/Q- and R-type IBa and those inhibited by DAMGO (1 μM). (b) Fractional components of L-, N-, P/Q- and R-type IBa and those inhibited by Orphanin FQ (1 μM). (c) Fractional components of L-, N-, P/Q- and R-type IBa and those inhibited by WIN55,212 (10 μM). The total height of the bars (open and hatched) represents the mean±s.e.m. contribution of the indicated VDCC type to the total IBa. The hatched bars represent the mean±s.e.m. inhibition by each agonist of the corresponding VDCC type. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of neurons tested.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the proposed signaling pathways responsible for opioid-, ORL-1- and CB1-receptor-mediated inhibition of VDCCs. The model is based on both the results from this study and the evidence reported in the literature. Activation of μ, κ opioid and ORL-1 receptor inhibited N- and P/Q-type VDCCs, whereas activation of CB1 receptor inhibited L-type VDCCs involving PKA pathways. Abbreviation for intracellular proteins: α, β and γ, G-protein subunits; AC, adenylate cyclase; PKA, protein kinase.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of opioid and cannabinoid on VDCCs in NTS. While Rhim & Miller (1994) have demonstrated DAMGO-induced inhibition of VDCCs in NTS, this is the first demonstration that μ- and κ-opioid receptors and ORL-1 receptor inhibit N- and P/Q-type VDCCs via Gαi-protein βγ subunits. The present study also demonstrates that CB1 receptors inhibit L-type VDCCs via Gαi-proteins involving PKA in NTS. Our present results, together with the result that administration of opioid and cannabinoid into NTS area regulates autonomic function, indicate the growing importance of opioid and cannabinoid in the regulation of NTS.

In several neurons, it has been reported that opioid and cannabinoid inhibit VDCCs. μ-Opioid receptor inhibits VDCCs in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG; Rusin & Moises, 1995), intracardiac neuron (Jeong et al., 1999), submandibular ganglion neuron (Endoh & Suzuki, 1998) and hippocampal neuron (Bushell et al., 2002). N/OFQ inhibits VDCCs in DRG (Abdulla & Smith, 1997), SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line (Conner et al., 1996), periaqueductal gray neuron (Beedle et al., 2004) and suprachiasmatic nucleus (Gompf et al., 2005). Cannabinoid inhibits VDCCs in neuroblastoma-glioma cell (Mackie & Hille, 1992) and hippocampal neuron (Twitchell et al., 1997).

According to biophysical criteria, the modes of modulation of VDCCs can be classified as voltage-dependent (VD) and a voltage-independent (VI). In the VD mode, inhibition of VDCCs is relieved at a higher potential or by means of a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse to positive voltage (Bean, 1989; Dolphin, 1996), whereas, in the VI mode, inhibition of VDCCs is not affected by a strong depolarizing voltage prepulse (Formenti et al., 1993). The G-proteins are heterotrimeric molecules with α, β and γ subunits. The VD-mode inhibition is mediated by a rapid ‘membrane delimited' pathway, probably involving the interaction of G-protein βγ subunits with the VDCCs (Herlitze et al., 1996; Ikeda, 1996), whereas the VI-mode inhibition is generally thought to involve a diffusible second messenger (Bernheim et al., 1991; Hille, 1994). Application of DAMGO, U69593 and Orphanin FQ produced a typical VD-mode inhibition of VDCCs characterized by slowed kinetic of activation and relieved by strong depolarizing voltage prepulse (Figures 1a–d). In contrast, application of WIN55,212 produced VI-mode inhibition of VDCCs in NTS.

In the present study, we further characterized the second messengers in opioid- and cannabinoid-induced inhibition of VDCCs. Treatment with adenylate cyclase inhibitor, intracellular application of PKA inhibitor, treatment with PKC inhibitor, treatment with PI3K inhibitor and treatment with MAPK inhibitor did not modulate DAMGO-, U69593- and Orphanin FQ-induced inhibition of VDCCs. In addition, these agonists produced VD-mode inhibition of VDCCs. Therefore, it can be considered that μ-, κ-opioid receptors and ORL-1 receptor inhibit VDCCs via G-protein βγ subunits. In contrast, treatment with adenylate cyclase inhibitor and intracellular application of PKA inhibitor attenuated the WIN55,212-induced inhibition of VDCCs. These results indicate that CB1 receptor inhibit VDCCs involving PKA in NTS. Several studies have also been demonstrated that activation of CB1 receptors reduces adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation in neurons via G-protein-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (Bidaut-Russell et al., 1990; Howlett, 1995; 1998).

There are some reports suggesting that the N/OFQ system may interact with the opioid system. For instance, in behavioral studies, both dynorphin (mediated by κ-opioid receptors) and N/OFQ diminish spatial learning in rats (Sandin et al., 1997; 1998). ORL-1 receptor is expressed throughout the brain and spinal cord (Anton et al., 1996; Mollereau & Mouledous, 2000). The presence of immunoreactivity for N/OFQ has also been reported throughout the CNS (Neal et al., 1999). Examination of these reports indicates that ORL-1 and immunoreactivity for N/OFQ are present in the NTS.

Alternatively, similar agonist and antagonist experiments demonstrated that opioid and N/OFQ are two independent systems in the NTS (Mao & Wang, 2005). It has been demonstrated that N/OFQ does not bind to μ-, δ- and κ-opioid receptors. Similarly, opioid ligands do not bind ORL-1 receptor (Reinscheid et al., 1995). In the present study, however, pretreatment of N/OFQ antagonist attenuates the DAMGO-induced inhibition of VDCCs. Similar results are reported by Hurlé et al. (1999). These authors demonstrated that ORL-1 receptor antagonist, [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2, antagonized κ-opioid receptor-induced inhibition of depolarization-induced intracellular Ca2+ increase. Interestingly, Butour et al. (1998) reported that ORL-1 receptor antagonist, [Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]NC(1–13)NH2, acted as an agonist in transformed CHO cells expressing the human ORL-1 receptor. Thus, opioid and ORL-1 receptor's function must be investigated in a further study.

Several hypotheses have been formulated to explain the interactions between opioid and cannabinoid systems, including the release of opioid peptide by cannabinoid, an interaction at the level of their signal-transduction mechanisms, or a direct interaction at the receptor level (Maldonado & Rodríguez de Fonseca, 2002). Indeed, opioid and cannabinoid receptors overlap in many brain areas, and a specific colocalization of μ-opioid receptor and CB1 receptor in the same neurons in striatum (Rodríguez et al., 2001) and lamina II of the dorsal horn (Salio et al., 2001) has been recently reported, indicating the existence of a possible reciprocal competition for the same pool of G-proteins in neurons containing these two receptors.

As mentioned above, administration of opioid, N/OFQ and cannabinoid into the NTS area elevated blood pressure and heart rate (Mao & Wang, 2000). NTS neurons can be divided into two groups, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic and glutamatergic (Mifflin & Felder, 1990; Brooks et al., 1992). N-, P- and Q-types VDCCs are implicated in transmitter release in CNS (Reuter, 1996). Several reports proposed that activation of opioid and ORL-1 receptor directly inhibits release of excitatory transmitters, such as glutamate, a proposed transmitter of primary baroreceptor afferents at the level of the NTS (Talman et al., 1980; Reis et al., 1981; Leone & Gordon, 1989; North, 1993). Reduction of glutamate release can result in reduction of NTS neuronal activity and thus increases in blood pressure and heart rate. In support of this, blockade of glutamate receptors in the NTS produces N/OFQ-like pressor and tachycardic responses (Ohta & Talman, 1994). In addition, N/OFQ indirectly results in an increase in release of inhibitory transmitter, such as GABA, an enriched transmitter in the NTS, which, like N/OFQ, can induce hypertension and tachycardia after intra-NTS injection (Bousquet et al., 1982; De Wildt et al., 1994; Barron et al., 1997). It also can be considered that opioid acts at μ- and/or ORL-1 opioid receptors on presynaptic terminals to inhibit glutamate release, and on postsynaptic opioid and/or cannabinoid receptors to reduce the activity of GABA neurons.

The ability of inhibiting L-type VDCCs singles out cannabinoid receptor from most receptors because non-L-type VDCCs modulation is quite common, whereas L-type VDCCs are rarely targeted in many neurons types so far examined (Viana & Hille, 1996; Abe et al., 2003; Endoh, 2004). Opioid and cannabinoid modulation of somatic Ca2+ influx, via L- and/or non-L-type VDCCs, could also potentially affect Ca2+-dependent gene expression and neuronal development (Murphy et al., 1991; Finkbeiner & Greenberg, 1996; Hardingham et al., 1997).

In conclusion, the present study in NTS demonstrated that postsynaptic opioid and cannabinoid receptors modulate neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission and Ca2+-dependent neuronal function using various signaling pathways in NTS. In this regard, however, experiments were performed in neonatal neurons. In fact, it has been demonstrated that aging alters the relative contributions of each VDCC subtype (Tanaka & Ando, 2001), opioid's receptor-binding affinity (Crisp et al., 1994) and opioid receptor's G-protein coupling (Talbot et al., 2004) in CNS neurons. Therefore, opioid and cannabinoid receptors' functions must be investigated in adults in a further study. It will also be important to investigate using a brain slice to synaptic transmission, as well as spike responses.

Abbreviations

- ω-Aga IVA

ω-agatoxin IVA

- ω-CgTx GVIA

ω-conotoxin GVIA

- DAMGO

[D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin

- DPDPE

[D-Pen2,5]-enkephalin

- GF109203X

2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide

- ICa

VDCC current

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- N/OFQ

nociceptin/Orphanin FQ

- Nif

nifedipine

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- ORL-1

opioid-receptor-like-1

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- VD

voltage-dependent

- VDCCs

voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

- VI

voltage-independent

References

- ABDULLA F.A., SMITH P.A. Nociceptin inhibits T-type Ca2+ channel current in rat sensory neurons by a G-protein-independent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:8721–8728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08721.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABE M., ENDOH T., SUZUKI T. Extracellular ATP-induced calcium channel inhibition mediated by P1/P2Y purinoceptors in hamster submandibular ganglion neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:1535–1543. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANTON B., FEIN J., TO T., LI X., SILBERSTEIN L., EVANS C.J. Immunohistochemical localization of ORL-1 in the central nervous system of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;368:229–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960429)368:2<229::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRON K.W., PAVELKA S.M., GARRETT K.M. Diazepam-sensitive GABA(A) receptors in the NTS participate in cardiovascular control. Brain Res. 1997;773:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00882-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAN B.P. Classes of calcium channels in vertebrate cells. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1989;51:367–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEEDLE A.M., McRORY J.E., POIROT O., DOERING C.J., ALTIER C., BARRERE C., HAMID J., NARGEOT J., BOURINET E., ZAMPONI G.W. Agonist-independent modulation of N-type calcium channels by ORL1 receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:118–125. doi: 10.1038/nn1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNHEIM L., BEECH D.J., HILLE B. A diffusible second messenger mediates one of the pathways coupling receptors to calcium channels in rat sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1991;6:859–867. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90226-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRENDERO F., MALDONADO R. Involvement of the opioid system in the anxiolytic-like effects induced by Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIDAUT-RUSSELL M., DEVANE W.A., HOWLETT A.C. Cannabinoid receptors and modulation of cyclic AMP accumulation in the rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUSQUET P., FELDMAN J., BLOCH R., SCHWARTZ J. Evidence for a neuromodulatory role of GABA at the first synapse of the baroreceptor reflex pathway. Effects of GABA derivatives injected into the NTS. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1982;319:168–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00503932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS P.A., GLAUM S.R., MILLER R.J., SPYER K.M. The actions of baclofen on neurons and synaptic transmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat in vitro. J. Physiol. 1992;457:115–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUNZOW J.R., SAEZ C., MORTRUD M., BOUVIER C., WILLIAMS J.T., LOW M., GRANDY D.K. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of a putative member of the rat opioid receptor gene family that is not a mu, delta or kappa opioid receptor type. FEBS Lett. 1994;347:284–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURKS T.F., GALLIGAN J.J., HIRNING L.D., PORRECA F. Brain, spinal cord and peripheral sites of action of enkephalins and other endogenous opioids on gastrointestinal motility. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 1987;11:44B–51B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSHELL T., ENDOH T., SIMEN A.A., REN D., BINDOKAS V.P., MILLER R.J. Molecular components of tolerance to opiates in single hippocampal neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61:55–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTOUR J.-L., MOISAND C., MOLLEREAU C., MEUNIER J.-C. Phe1Ψ(CH2-NH)Gly2]nociceptin-(1–13)-NH2 is an agonist of the nociceptin (ORL1) receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;349:R5–R6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNER M., YEO A., HENDERSON G. The effect of nociceptin on Ca2+ channel current and intracellular Ca2+ in the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:205–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRISP T., STAFINSKY J.L., HOSKINS D.L., PERNI V.C., URAM M., GORDON T.L. Age-related changes in the spinal antinociceptive effects of DAGO, DPDPE, and β-endorphin in the rat. Brain Res. 1994;643:282–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE WILDT D.J., VAN DER VEN J.C., BERGEN P.V., LANG H.D., VERSTEEG D.H.G. A hypotensive and bradycardic action of γ2-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (γ2-MSH) microinjected into the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1994;349:50–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00178205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEL TACCA M., BERNARDINI C., CORSANO E., SOLDANI G., ROZE C. Effects of morphine on gastric ulceration, barrier mucus and acid secretion in pylorusligated rats. Pharmacology. 1987;35:174–180. doi: 10.1159/000138309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLPHIN A.C. Facilitation of Ca2+ current in excitable cells. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)81865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDOH T. Characterization of modulatory effects of postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors on calcium currents in rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res. 2004;1024:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDOH T. Involvement of Src tyrosine kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase in the facilitation of calcium channels in rat nucleus tractus solitarius by angiotensin II. J. Physiol. 2005;568:851–865. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENDOH T., SUZUKI T. The regulating manner of opioid receptors on distinct types of calcium channels in hamster submandibular ganglion cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 1998;43:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(98)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FINKBEINER S., GREENBERG M.E. Ca2+-dependent routes to Ras: mechanisms for neuronal survival, differentiation, and plasticity. Neuron. 1996;16:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORMENTI A., ARRIGONI E., MANCIA M. Two distinct modulatory effects on calcium channels in adult rat sensory neurons. Biophys. J. 1993;64:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMPF H.S., MOLDAVAN M.G., IRWIN R.P., ALLEN C.N. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) inhibits excitatory and inhibitory synaptic signaling in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) Neuroscience. 2005;132:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDINGHAM G., CHAWLA S., JOHNSON C., BADING H. Distinct functions of nuclear and cytoplasmic calcium in the control of gene expression. Nature. 1997;385:260–265. doi: 10.1038/385260a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflu"gers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENDERSON G., MCKNIGHT A.T. The orphan opioid receptor and its endogenous ligand-nociceptin/orphanin FQ. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERLITZE S, GARCIA D.E., MACKIE K., HILLE B., SCHEUER T., CATTERALL W.A. Modulation of Ca2+ channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:258–262. doi: 10.1038/380258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HILLE B. Modulation of ion-channel function by G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLISTER L.H.Health aspects of cannabis use The Cannabinoids: Chemical, Pharmacological and Therapeutic Aspects 1984New York: Academic Press; 3–20.ed. Agurell, S., Dewey, W.L. & Willette, R.E. pp [Google Scholar]

- HOWLETT A.C. Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995;35:607–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOWLETT A.C. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor in the brain. Neurobiol. Dis. 1998;5:405–416. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HURLÉ M.A., SÁNCHEZ A., GARCÍA-SANCHO J. Effects of κ- and μ-opioid receptor agonists on Ca2+ channels in neuroblastoma cells: involvement of the orphan opioid receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;379:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IKEDA R.S. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels by G-protein βγ subunits. Nature. 1996;380:255–258. doi: 10.1038/380255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIBASHI H., RHEE J.S., AKAIKE N. Regional difference of high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels in rat CNS neurons. Neuroreport. 1995;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199508000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEAN A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:929–969. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEONG S.-W., IKEDA S.R., WURSTER R.D. Activation of various G-protein coupled receptors modulates Ca2+ channel currents via PTX-sensitive and voltage-dependent pathways in rat intracardiac neurons. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1999;7:68–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOTZ C.M., BILLINGTON C.J., LEVINE A.S. Opioids in the nucleus of the solitary tract are involved in feeding in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:R1028–R1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAWRENCE A., JARROTT B. Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Prog. Neurobiol. 1996;48:21–53. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONE C., GORDON F.J. Is L-glutamate a neurotransmitter of baroreceptor information in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;250:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKIE K., HILLE B. Cannabinoids inhibit N-type calcium channels in neuroblastoma-glioma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3825–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R.Opioid system involvement in cannabinoid tolerance and dependence Molecular Biology of Drug Addition 2003Totowa, NJ: Human Press Inc; 221–245.ed. Maldonado, R. pp [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R., RODRÍGUEZ DE FONSECA F. Cannabinoid addiction: behavioral models and neuronal correlates. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:3326–3331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03326.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANZANARES J., CORCHERO J., ROMERO J., FERNANDEZ-RUIZ J.J., RAMOS J.A., FUENTES J.A. Pharmacological and biochemical interactions between opioids and cannabinoids. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:287–294. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAO L., WANG J.Q. Microinjection of nociceptin (Orphanin FQ) into nucleus tractus solitarii elevates blood pressure and heart rate in both anesthetized and conscious rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;273:248–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAO L., WANG J.Q. Cardiovascular responses to microinjection of nociceptin and endomorphin-1 into the nucleus tractus solitarii in conscious rats. Neuroscience. 2005;132:1009–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUDA L.A., LOLAIT S.J., BROWNSTEIN M.J., YOUNG A.C., BONNER T.I. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEUNIER J.C., MOLLEREAU C., TOLL L., SUAUDEAU C., MOISAND C., ALVINERIE P., BUTOUR J.-L., GUILLEMNOT J.-C., FERRARA P., MONSARRAT B., MAZAGULL H., VASSART G., PARMENTIRER M., BOSTENTIN J. Isolation and structure of the endogenous agonist of opioid receptor-like ORL1 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:532–535. doi: 10.1038/377532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIFFLIN S.W., FELDER R.B. Synaptic mechanisms regulating cardiovascular afferent input to solitary tract nucleus. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;28:H653–H661. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.3.H653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLLEREAU C., MOULEDOUS L. Tissue distribution of the opioid receptor-like (ORL1) receptor. Peptides. 2000;21:907–917. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONORY K., BOURIN M.C., SPETEA M., TOMBOLY C., TOTH G., MATTHES H.W., KIEFFER B.L., HANOUNE J., BORSODI A. Specific activation of the μ opioid receptor (MOR) by endomorphin 1 and endomorphin 2. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:577–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURPHY T., WORLEY P., BARABAN J. L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels mediate synaptic activation of immediate early genes. Neuron. 1991;7:625–635. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90375-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEAL C.R., MANSOUR A., REINSCHEID R., NOTHACKER H.-P., CIVELLI O., WATSON S.J. Localization of orphanin FQ (Nociceptin) peptide and messenger RNA in the central nervous system of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;406:503–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORTH R.A.Presynaptic actions of opioids Presynaptic Receptors in the Mammalian Brain 1993Boston: Birkhäuser; 71–86.ed. Dunwiddie T.V. & Lovinger D.M. pp [Google Scholar]

- OHTA H., TALMAN W.T. Both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors in the NTS participate in the baroreceptor reflex in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:R1065–R1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.4.R1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PADLEY J.R., LI Q., PILOWSKY P.M., GOODCHILD A.K. Cannabinoid receptor activation in the rostal ventrolateral medulla oblongata evokes cardiorespiratory effects in anesthetized rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:384–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATON J.F.R., KASPAROV S. Differential effects of angiotensin II on cardiorespiratory reflexes mediated by nucleus tractus solitarii – a microinjection study in the rat. J. Physiol. 1999;521:213–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERTWEE R.G. Cannabinoid receptors and pain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001;63:569–611. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFITZER T., NIEDERHOFFER N., SZABO B. Central effects of the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55212-2 on respiratory and cardiovascular regulation in anaesthetized rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;142:943–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REINSCHEID R.K., ARDATI A., MONSMA F.J., JR, CIVELLI O. Structure–activity relationship studies on the novel neuropeptide orphanin FQ. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14163–14168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REINSCHEID R.K., NOTHACKER H.P., BOURSON A., ARDATI A., HENNINGSEN R.A., BUNZOW J.R., GRANDY D.K., LANGEN H., MONSMA F.J., JR, CIVELLI O. Orphanin FQ: a neuropeptide that activates an opioidlike G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1995;270:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REIS D.J., GRANATA A.R., PERRONE M.H., TALMAN W.T. Evidence that glutamate acid is the neurotransmitter of baroreceptor afferent terminating in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1981;3:321–334. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(81)90073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REUTER H. Diversity and function of presynaptic calcium channels in the brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996;6:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHIM H., MILLER R.J. Opioid receptors modulate diverse types of calcium channels in the nucleus tractus solitarius of the rat. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:7608–7615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07608.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHIM H., TOTH P., MILLER R.J. Mechanism of inhibition of calcium channels in rat nucleus tractus solitarius by neurotransmitters. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:1341–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODRÍGUEZ J.J., MACKIE K., PICKEL V.M. Ultrastructural localization of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in μ-opioid receptor patches of the rat caudate putamen nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:823–833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-00823.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUSIN K.I., MOISES H.C. μ-Opioid receptor activation reduce multiple components of high-threshold calcium current in rat sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4315–4327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04315.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALIO C., FISCHER J., FRANZONI M.F., MACKIE K., KANEKO T., CONRATH M. CB1-cannabinoid and mu-opioid receptor co-localization on post-synaptic target in the rat dorsal horn. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3689–3692. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDIN J., GEORGIEVA J., SCHÖTT P.A., ÖGREN S.O., TERENIUS L. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ microinjected into hippocampus impairs spatial learning in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1997;9:194–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDIN J., NYLANDER I., GEORGIEVA J., SCHO"TT P.A., O"GREN S.O., TERENIUS L. Hippocampal dynorphin B injections impair spatial learning in rats: a κ-opioid receptor-mediated effect. Neuroscience. 1998;85:375–382. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAPRU H.N., PUNNEN S., WILLETTE R.N.Role of enkephalins in ventrolateral medullary control of blood pressure Brain Peptides and Catecholamines in Cardiovascular Regulation in Normal and Disease States 1987New York: Raven Press; 153–168.ed. Buckley, J.P., Ferrario, C. & Lokhandwala, M. pp [Google Scholar]

- TALBOT J.N., HAPPE H.K., MURRIN L.C. μ Opioid receptor coupling to Gi/o proteins increases during postnatal development in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;314:596–602. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TALMAN W.T., PERRONE M.H., REIS D.J. Evidence for L-glutamate as the neurotransmitter of baroreceptor afferent nerve fibers. Science. 1980;209:813–815. doi: 10.1126/science.6105709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANAKA Y., ANDO S. Age-related changes in the subtypes of voltage-dependent calcium channels in rat brain cortical synapses. Neurosci. Res. 2001;39:213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TWITCHELL W., BROWN S., MACKIE K. Cannabinoids inhibit N- and P/Q-type calcium channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:43–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UHL G.R., CHILDERS S., PASTERNAK G. An opiate-receptor gene family reunion. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIANA F., HILLE B. Modulation of high voltage-activated calcium channels by somatostatin in acutely isolated rat amygdaloid neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6000–6011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06000.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG S., YU L. Identification of dynorphins as endogenous ligands for an opioid receptor-like orphan receptor. J. Neurosci. 1995;270:22772–22776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]