Abstract

Envenomation by the snake Bothrops jararaca is typically associated with hemostatic abnormalities including pro- and anticoagulant disturbances. Glycyrrhizin (GL) is a plant-derived thrombin inhibitor that also exhibits in vivo antithrombotic properties. Here, we evaluated the ability of GL to counteract the hemostatic abnormalities promoted by B. jararaca venom.

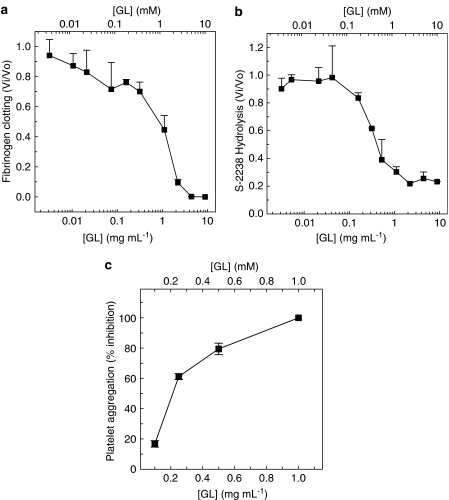

GL inhibited the human fibrinogen clotting (IC50=∼1.0 mg ml−1; 1.2 mM), H-D-phenylalanyl-L-pipecolyl-L-arginine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride hydrolysis (IC50=∼0.4 mg ml−1; 0.47 mM) and platelet aggregation (IC50=∼0.28 mg ml−1; 0.33 mM) induced by B. jararaca venom, in vitro.

The in vivo effect of GL was tested in rats using a model of venous thrombosis in which intravenous (i.v.) administration of B. jararaca venom (100 μg kg−1) produced in all animals a thrombus with a mean weight of 10.6±1.7 mg.

Prior administration of GL (180 mg kg−1) or antibothropic serum (27 μl kg−1) inhibited thrombus formation by 86 and 67%, respectively. Remarkably, co-administration of ineffective doses of GL and antibothropic serum markedly decreased thrombus weight, suggesting a synergistic effect.

Co-administration of GL with antibothropic serum abolished venom-induced bleeding. Ex vivo clotting times showed that rat plasma was non-clotting after i.v. administration of B. jararaca venom. Treatment with GL, antibothropic serum or both before venom administration efficiently prevented this abnormality.

Altogether, we demonstrate here that GL prevents both in vitro and in vivo venom-induced changes in hemostasis, suggesting a potential antiophidic activity.

Keywords: Glycyrrhizin, B. jararaca venom, venous thrombosis, antibothropic serum

Introduction

In Brazil, snakebite accidents represent an important public health problem, with the genus Bothrops (including the species B. jararaca, B. moojeni, B. erythromelas and B. atrox) being responsible for more than 90% of the registered cases (Cardoso, 1990). A number of proteins from bothropic venoms interfere with the hemostatic system and have been characterized in detail (Markland, 1998; Castro et al., 2004) as procoagulant, anticoagulant or fibrinolytic factors (Marsh, 1994). In addition, several components may alter platelet function displaying either pro- or antiaggregating properties (Markland, 1998). The signs and symptoms presented by patients include local (pain, swelling, ecchymosis and necrosis) and systemic (blood incoagulability, hemorrhage) manifestations (Kamiguti et al., 1986; Maruyama et al., 1990). Envenomation by these snakes generally results in strong coagulopathy with persistent bleeding owing to fibrinogen degradation as well as consumption of blood coagulation factors (Maruyama et al., 1990; Kamiguti et al., 1991). On the other hand, massive blood clotting activation may cause thrombosis in small vessels (Thomas et al., 1995). Therefore, severe cases of envenomotion may lead to permanent tissue loss, disability or amputation.

The effective therapeutic treatment for ophidian accidents nowadays is serotherapy (Heard et al., 1999). Nevertheless, alternative medication has been proposed. The use of heparin was first proposed in the late 40s (Ahuja et al., 1946). Although it is a well-known anticoagulant, heparin does not neutralize the thrombin-like activity of bothropic venoms and does not prevent the defibrinogenating syndrome induced by these venoms (Nahas et al., 1975). In fact, structural differences between thrombin and venom-derived thrombin-like enzymes impair the inhibitory action of heparin–antithrombin complex as well as other coagulation inhibitors such as hirudin (Castro et al., 2004).

A number of studies have also reported the use of plants (or their extracts) known in popular medicine for treatment of snakebite (Mors et al., 1989; 2000; Mors, 1991; Martz, 1992; Houghton & Osibogun, 1993; Houghton & Skari, 1994). Among these studies, some focus on the inhibition of snake venom hemostatic effects. Extracts from plants widely used in India, Sri Lanka and West Africa showed significant dose-related prolongation of Echis carinatus venom-induced clot formation in human plasma (Onuaguluchi & Okeke, 1989). It has also been shown that the extract of the Brazilian plant Marsypianthes chamaedrys inhibits fibrinogen clotting induced by several Brazilian snake venoms, indicating that it affects thrombin-like enzymes (Castro et al., 2003).

Glycyrrhizin (GL) is a natural triterpenoid saponin extracted from the root of a Legumisosae, Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice), with a molecular mass of 840 Da. This compound is known for its anti-inflammatory activity (Fogden & Neuberger, 2003) and has been also characterized as a thrombin inhibitor (Francischetti et al., 1997). Thrombin, which plays a central role in the hemostatic system, displays very high specificity upon a small range of substrates. This is particularly attributed to the presence of two positively charged regions that are located at a distance from its catalytic site, named ‘anion-binding exosites', which play major roles in the recognition of substrates and inhibitors (Stubbs & Bode, 1995). In fact, it was demonstrated that GL binds to thrombin exosite 1 and blocks the enzyme action upon fibrinogen and platelets (Francischetti et al., 1997), displaying a similar mechanism to that described for the C-terminal hirudin-based non-apeptide (Krstenansky & Mao, 1987). Further studies demonstrated that GL has in vivo antithrombotic properties (Mendes-Silva et al., 2003).

Based on the known coagulopathy state generated by the envenomation, we attempted to evaluate the ability of GL to counteract this condition caused by B. jararaca venom. For this purpose, we injected crude venom intravenously in rats and measured thrombus formation, ex vivo clotting times and bleeding effect. GL was effective both in vitro and in vivo. Also, GL showed a synergistic effect when combined with antibothropic serum. Our data indicate that in vitro experiments combined with the animal model herein described would be useful to evaluate compounds with potential ability to reduce the venom-induced hemostatic abnormalities.

Methods

Material and drugs

Lyophilized B. jararaca venom and polyvalent horse antibothropic serum were kindly provided by Instituto Butantan (São Paulo, SP, Brazil). GL was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). The drug was dissolved in 50 mM NaOH at 37°C and pH was adjusted to 7.4 using 1 M Tris-HCl. Human α-thrombin was purified from frozen human plasma samples following the method described by Ngai & Chang (1991). All other reagents were of analytical grade. Human fibrinogen was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, U.S.A.). S-2238 (H-D-phenylalanyl-L-pipecolyl-L-arginine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride), a chromogenic substrate for thrombin, was obtained from Chromogenix (Mölndal, Sweden). Reagents for determination of APTT (cephalin plus kaolin) and PT (thromboplastin with calcium) were from BioMériaux (RJ, Brazil). Anasedan (Xylazin) and Dopalen (Ketamin) were from Agribrands (RJ, Brazil). Silicone tubing (0.9 × 25 mm) BD Insyte™ was purchased from Dickinson Ind. Cirúrgicas (Minas Gerais, Brazil).

Assay for fibrinogen clotting

Fibrinogen clotting by snake venom was measured in 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% polyethyleneglycol (PEG) 6.000, pH 7.4, using a Thermomax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA, U.S.A.) equipped with a microplate mixer and heating system as described (Francischetti et al., 1999). B. jararaca venom (0.01 μg ml−1) was incubated for 5 min at 37°C with various concentrations of GL and reaction was started by addition of human fibrinogen (2 mg ml−1, final concentration). The total volume of the reactions was 100 μl. The initial rate of fibrinogen clotting was determined from the increase in the Abs405 at 6-s intervals.

Assay for S-2238 hydrolysis

Hydrolysis of the synthetic substrate S-2238 by snake venom was measured in 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl and 0.1% PEG 6.000, pH 7.4 using the reader described above. B. jararaca venom (0.01 μg ml−1) was incubated for 5 min at 37°C with various concentrations of GL and reaction was started by addition of S-2238 (100 μM, final concentration). The total volume of the reaction mixture was 100 μl. The initial rate of the p-nitroaniline release was determined from the increase in the Abs405 at 6-s intervals.

Platelet aggregation assays

Washed rabbit platelets were obtained from blood anticoagulated with 5 mM EDTA. Platelets were isolated by centrifugation and washed twice according to Zingali et al. (1993) with calcium-free Tyrode's buffer, pH 6.5, containing 0.1% glucose, 0.2% gelatin, 0.14 M NaCl, 0.3 M NaHCO3, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 2.7 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EGTA. Washed platelets were resuspended in a modified Tyrode's buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM CaCl2 at 300,000–400,000 cells μl−1. Assays were performed at 37°C using a Chronolog Aggregometer (Havertown, PA, U.S.A.). Aggregation in the volume of 350 μl was induced by B. jararaca venom (17.5 μg ml−1). Inhibition of platelet aggregation was tested by adding GL, at various concentrations, 1 min before induction with venom. The inhibition was calculated using the maximum peak height tracing, which was compared with control values obtained in the absence of the drug.

Stasis-induced thrombosis after injection of snake venom

A deep venous thrombosis model in rats was developed by adapting the method described by Mendes-Silva et al. (2003) with slight modifications. Thrombus formation was induced by a combination of stasis and hypercoagulability produced by intravenous (i.v.) administration of B. jararaca venom. Wistar rats weighing 170–250 g were anesthetized with xylazin (16 mg kg−1, i.m.) followed by ketamin (100 mg kg−1, i.m.). The abdomen was surgically opened, and after careful incision the vena cava was exposed and dissected free from surrounding tissue. Two loose ligatures were prepared 1 cm apart on the inferior vena cava just below the left renal vein. B. jararaca snake venom at different doses was injected into the vena cava (below the distal loose suture) and stasis was immediately established by tightening the proximal suture. The distal suture was tightened 20 min after administration of venom solution and the ligated segment was removed. The formed thrombus was detached from the segment, rinsed, blotted on filter paper, dried for 1 h at 60°C and weighed. The ability of GL and/or antibothropic serum to inhibit thrombus formation was evaluated using venom doses of 100 μg kg−1 body weight. In this case, GL and/or antibothropic serum at the indicated doses were administered intravenously (below the distal loose suture) 5 min before thrombosis induction. The protocol received official approval with regard to the care and use of laboratory animals. Data presented represent mean±s.d. of 5–10 animals.

Ex vivo determination of APTT and PT

Rat's carotid artery was carefully exposed and dissected free from surrounding tissue. Saline, GL and/or antibothropic serum were injected 5 min before administration of B. jararaca venom (100 μg kg−1 body weight) through a silicone tubing inserted into the carotid artery. The same device was used to collect blood samples (0.6 ml in 3.8% trisodium citrate, 9:1 v v−1) after venom administration (0–120 min). Blood samples were centrifuged (2000 × g, 10 min), and the platelet-poor plasma was stored at −20°C until use. APTT and PT were measured on an Amelung KC4A Coagulometer as follows. For APTT tests, cephalin plus kaolin (APTT reagent, BioMériaux, RJ, Brazil) were incubated for 1 min with 50 μl of pre-warmed plasma (37°C). The reaction was started by addition of 100 μl of pre-warmed CaCl2 (25 mM). For PT tests, 50 μl of pre-warmed plasma was incubated for 2 min (37°C) and reaction was started by addition of 100 μl of pre-warmed thromboplastin with calcium (PT reagent, BioMériaux, RJ, Brazil).

Bleeding effect

For evaluation of the bleeding effect, the carotid artery was carefully exposed and dissected free from surrounding tissue. B. jararaca venom was administered at the indicated doses through a silicone tubing inserted into the carotid artery. Five minutes after venom administration, the rat's tail was cut 3 mm from the tip and immersed in 40 ml of distilled water at room temperature. Blood loss was evaluated 60 and 120 min later as a function of absorbance at 540 nm due to the hemoglobin content in water solution (Herbert et al., 1996). The absorbance detected for a control group that received saline instead of venom was taken as control blood loss. For evaluation of the antiophidic activity, GL and/or antibothropic serum were injected 5 min before the administration of venom (100 μg kg−1 body weight) through the same device described above.

Statistics

All data presented represent mean±s.d. Differences in mean values were analyzed using Student's t-test. When more than one group was compared with one control, significance was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically signicant.

Results

In order to determine whether GL could prevent the hemostatic disturbances induced by B. jararaca venom, we first tested the drug using in vitro assays. Figure 1a shows that increasing GL concentrations caused a progressive inhibitory effect upon venom-induced human fibrinogen clotting, with an IC50 of ∼1.0 mg ml−1 (1.2 mM). GL was also tested against venom-induced hydrolysis of the synthetic thrombin substrate S-2238. Again, GL showed a dose-dependent pattern of inhibition of the venom's hydrolytic activity (Figure 1b), with an IC50 of ∼0.4 mg ml−1 (0.47 mM). These results differ from those previously reported for human α-thrombin (Francischetti et al., 1997). It has been observed that GL inhibits thrombin-induced fibrinogen clotting, whereas the S-2238 hydrolysis is significantly increased. We further evaluated the ability of GL to interfere with venom-induced platelet aggregation. As seen in Figure 1c, GL inhibited this biological activity in a dose-dependent fashion, with an IC50 of ∼0.28 mg ml−1 (0.33 mM).

Figure 1.

Effect of GL on the enzymatic activity of B. jararaca venom. (a) The effect of increasing GL concentrations on human fibrinogen (2 mg ml−1) clotting induced by B. jararaca venom (0.01 μg ml−1) was investigated. Experiments were performed at 37°C in 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG 6.000, pH 7.4. Ordinates, Vi/Vo, initial rate of fibrinogen clotting in the presence of GL/initial rate in its absence. Data represent mean±s.d. of three determinations. (b) Effect of increasing GL concentrations on S-2238 (100 μM, final concentration) hydrolysis induced by B. jararaca venom (0.01 μg ml−1). Ordinates, Vi/Vo, initial rate of S-2238 hydrolysis in the presence of GL/initial rate in its absence. (c) Effect of GL, at the indicated doses, on venom-induced (17.5 mg ml−1) platelet aggregation was performed as described in the Methods section. Data represent mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

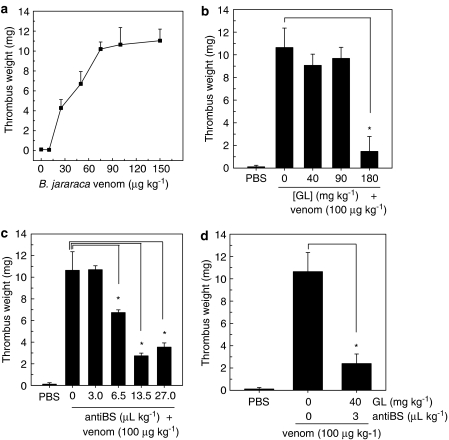

For evaluation of the in vivo antiophidic effect, we have established a venous thrombosis model in rats in which thrombosis is induced by B. jararaca venom administration combined with stasis. Venom doses above 10 μg kg−1 caused a thrombus to form in 100% of the rats (Figure 2a). The group of animals that received venom doses of 150 μg kg−1 had thrombus weight of 11.4±1.2 mg but showed 80% mortality during the surgical procedure. A common feature for low-venom doses (10 and 25 μg kg−1) was a significant blood extravasation after i.v. inoculation whereas the high venom doses (50–150 μg kg−1) resulted in significant thrombus formation beyond the segment dissected free from surrounding tissue.

Figure 2.

Effect of GL and antibothropic serum on thrombus weight after administration of B. jararaca venom in the rat. (a) B. jararaca venom was administered intravenously at the indicated doses and stasis was immediately established for induction of thrombosis, as described in Methods. (b) GL was administered intravenously at the indicated doses 5 min before the induction of thrombosis by venom (100 μg kg−1) combined with stasis. (c) Antibothropic serum was administered intravenously at the indicated doses 5 min before the induction of thrombosis by venom (100 μg kg−1) combined with stasis. (d) GL and antibothropic serum (As) were co-administrated intravenously 5 min before the induction of thrombosis by venom (100 μg kg−1) combined with stasis. Each point represents mean±s.d. of 5–10 animals. Asterisk, P<0.05.

I.v. administration of GL doses of 180 mg kg−1 produced a significant inhibition of 86% in thrombus weight (1.5±1.3 mg) against 100 μg kg−1 venom doses (Figure 2b). No effect was observed with lower GL doses. Similar assays performed with antibothropic serum doses of 13.5 and 27 μl kg−1 decreased by 75 and 67% (2.7±0.3 and 3.5±0.4 mg), respectively, the thrombus weight produced by 100 μg kg−1 of venom (Figure 2c).

We further tested the ability of a combination of GL and antibothropic serum to counteract venom-induced thrombus formation (Figure 2d). Co-administration of 40 mg kg−1 of GL with 3 μl kg−1 of antibothropic serum decreased thrombus weight by 76% (2.4±0.8 mg). It is worth emphasizing that these GL or antibothropic serum doses were not effective when given alone (9.1±0.9 and 10.7±0.4 mg thrombus weight, respectively).

The ex vivo clotting tests were evaluated using PT and aPTT tests (Table 1). Blood collected immediately or 10 min after the venom administration clotted instantly before tests could be performed. Both tests showed non-clotting plasma samples 30 or 120 min after B. jararaca administration (100 μg kg−1). These observations are consistent with fibrinogen consumption. On the other hand, animals that were pretreated with GL (40 mg kg−1), antibothropic serum (27 μl kg−1) or both GL and antibothropic serum (40 mg kg−1 and 3 μl kg −1, respectively) before venom administration showed significant protection against venom effects. Both PT and APTT (Table 1) were slightly increased as compared to control animals treated with saline (PT=25.7±2.8 s; APTT=23.5±1.8 s). Interestingly, pretreatment with GL (180 mg kg−1) showed non-clotting plasma for samples collected 10, 30 or 120 min after B. jararaca administration (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of B. Jararaca venom and GL and/or antibothropic serum treatments on ex vivo clotting tests

|

Animal group |

Clotting times |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPTT (s) | PT (s) | |||||

| Control |

23.5±1.8 |

25.7±2.8 |

||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Time after venom administration (min) |

|||||

| Treated with |

10 |

30 |

120 |

10 |

30 |

120 |

| Venom1 |

C |

NC |

NC |

C |

NC |

NC |

| Venom1+GL2 |

25.4±0.4 |

28.2±1.5 |

19.1±2.6 |

33.8±9.3 |

32.3±0.8 |

42.6±8.0 |

| Venom1+As3 |

31.9±5.4 |

29.2±3.6 |

36.7±12.6 |

35.5±3.7 |

37.1±6.2 |

50.8±2.2 |

| Venom1+GL2+As4 | C | 22.4±1.3 | 38.5±4.3 | C | 26.6±2.6 | 52.2±2.5 |

PT and APTT clotting times were measured as described in Methods. Citrated plasma samples were taken at the indicated times from animals treated as described: 1B. jararaca venom, 100 μg kg−1; 2GL, 40 mg kg−1, antibothropic serum, 3As, 27 μl kg−1 or 4As, 3 μl kg−1. Data show mean±s.d. of at least five animals.

C means that blood clotted before tests could be performed.

NC means that plasma did not clot until 150 s.

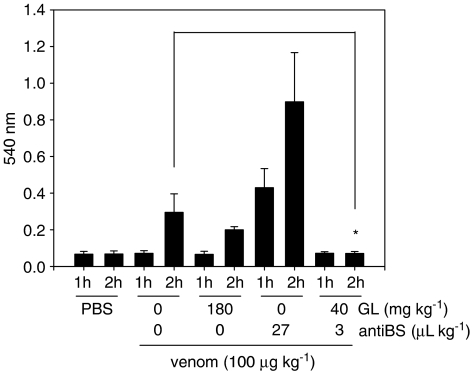

The antivenom action of GL was further evaluated using a venom-induced bleeding model. Figure 3 shows that venom doses of 100 μg kg−1 increased the hemorrhage by ∼4-fold, after 2 h of venom administration. A mild bleeding starts to be observed after ∼40 min of venom injection (not shown). Interestingly, we also observed a strong hematuria in most animals that received these venom doses (data not shown). Treatment with GL (180 mg kg−1) was not able to decrease the venom-induced bleeding, although it completely abolished hematuria (data not shown). Most striking was the observation that treatment of animals with antibothropic serum (27 μl kg−1) caused a dramatic increase in the venom-induced bleeding. Antivenom increased the hemorrhage by six- and three-fold after 1 and 2 h, respectively. At this point, it is possible that these effects are derived from the neutralization of specific venom components, possibly those with clotting activity. The combined action of GL and antibothropic serum was further evaluated. Co-administration of GL (40 mg kg−1) and antibothopic serum (3.0 μl kg−1) completely abolished the venom-induced bleeding. Also, no hematuria was observed in animals receiving this treatment (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of GL and antibothropic serum on venom-induced hemorrhage. The effects of GL and/or antibothropic serum (at the indicated doses) on the bleeding effect caused by B. jararaca venom (100 μg kg−1) were evaluated 60 and 120 min later as described in the section Ex vivo determination of APTT and PT. The absorbance detected for a control group that received saline instead of B. jararaca venom was taken as control blood loss. Results shown represent mean±s.d. of 5–10 animals. Asterisk, P<0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, GL was identified as a compound displaying inhibitory effects towards the hemostatic abnormalities induced by B. jararaca venom. As previously reported for human α-thrombin (Francischetti et al., 1997), GL decreased the venom-induced fibrinogen clotting (Figure 1a). On the other hand, whreas GL did not inhibit the thrombin catalytic site, it strongly decreased the S-2238 hydrolysis by snake venom (Figure 1b). We speculate that these observations arise from differences among thrombin and the thrombin-like enzymes found in the venom (Castro et al., 2004). In fact, it was shown that GL binds to the so-called anion-binding exosite on thrombin, a region that is important for the recognition of macromolecular substrates such as fibrinogen (Stubbs & Bode, 1995; Francischetti et al., 1997). There is no evidence of similar regions on thrombin-like enzymes from snake venoms (Castro et al., 2004).

The presence of components interfering with platelets in vitro is well known in B. jararaca venom (Markland, 1998). These factors seem to contribute to the coagulopathy observed in envenomed patients (Maruyama et al., 1990; Kamiguti et al., 1991). In this context, as previously shown with α-thrombin (Francischetti et al., 1997), GL inhibited venom-induced platelet aggregation.

Here we demonstrate for the first time an experimental venous thrombosis model induced by i.v. administration of B. jararaca venom combined with stasis. Venom doses above 10 μg kg−1 body weight caused 100% incidence of thrombus (Figure 2a). This effect may result from the combined action of proteins that activate the blood coagulation cascade, such as factor X-activating components, thrombin-like enzymes and platelet-activating compounds (Nahas et al., 1979; Markland, 1998; Castro et al., 2004). This procoagulant effect is very rapid and leads to a subsequent bleeding effect (Kamiguti et al., 1991). This may explain why venous thrombosis is rarely observed in patients, whereas the non-coagulating blood associated with local and/or systemic bleeding is a common feature (Kamiguti et al., 1986; Maruyama et al., 1990).

GL was highly effective in preventing venom-induced thrombus formation (Figure 2b). This is in agreement with a previous study demonstrating that GL inhibits thrombus formation in a similar animal model in which the hypercoagulability state is produced by i.v. administration of a thromboplastin solution (Mendes-Silva et al., 2003). Comparing in vivo (thrombosis model) with in vitro (fibrinoclotting) effects of GL, we observed that a four-fold higher concentration of GL (1.8 and 0.42 mg μg−1 of venom, respectively) is necessary in vivo for the complete inhibition of the clotting action of this venom. These data indicate that other venom/plasma components that contribute to the thrombus formation might be inactivated by GL. These may include thrombin generated by prothrombin activators (Markland, 1998) and platelet-activating components (see Figure 1c).

Venom-induced thrombus formation was also inhibited by an antibothropic serum (Figure 2c), but a maximum of only ∼75% inhibition was achieved at the highest antivenom doses. Remarkably, the association of GL and antibothropic serum, at doses that showed no significant inhibitory effects when given alone, strongly decreased venom-induced thrombus formation (Figure 2d).

It is well established that envenomation by B. jararaca leads to fibrinogen consumption, as observed in humans as well as in animal models using dogs and rats (Maruyama et al., 1990; Burdmann et al., 1993; Sano-Martins et al., 1995). Therefore, we decided to express blood-clotting function using PT and APTT tests. As they are well-correlated with fibrinogen levels, an elevation of these clotting times would be expected if fibrinogen consumption was taking place. This was observed in animals that were treated with venom alone. On the contrary, as seen in Table 1, treatment with low doses of GL, antibothropic serum or both kept PT and aPTT values close to normal strongly suggesting that fibrinogen consumption was partially impaired. It is interesting to observe that significantly higher GL doses were necessary to decrease in vivo thrombus formation (180 mg kg−1) as compared to effects on ex vivo clotting of plasma (40 mg kg−1). A possible explanation is that the combination of stasis with i.v. administration of venom in the in vivo thrombus model confines a higher concentration of procoagulant factors within a vessel compartment, whereas ex vivo clotting tests were performed in blood samples collected from animals that received GL and venom that freely circulated during the treatment. Another striking feature is that high GL doses (180 mg kg−1) completely impaired plasma clotting for samples collected 10, 30 or 120 min after venom administration, suggesting an effective protection against the early procoagulant events.

The in vivo properties of GL against B. jararaca venom were also evaluated in a bleeding model (Figure 3). GL alone was not able to impair venom-induced bleeding. In fact, GL (180 mg kg−1) produces bleeding itself, as previously shown (Mendes-Silva et al., 2003). To our surprise, the antibothropic serum used in this study strongly potentiated the hemorrhage caused by venom administration. This effect is clearly demonstrated here for the first time, and points to an issue that should be systematically tested, especially when high doses of antivenom are used. At this point, we cannot explain these observations, although we can propose that perhaps anticoagulant molecules, present in this venom (Kamiguti et al., 1986; 1991), are poorly neutralized by this anti-serum. Nevertheless, this hypothesis has yet to be proven. On the other hand, the association of GL and antivenom was highly effective in preventing bleeding in this animal model.

Altogether, our data support that the association of GL with antibothropic serum efficiently counteracts the in vivo hemostatic abnormalities evoked by B. jaracaca venom in an animal model. However, it is worth emphasizing that rather than being a model that mimics an envenomation accident, the animal model described here seems more useful for the study of molecules that could potentially neutralize the hemostatic abnormalities caused by the envenomation. Drugs were administered before the challenge with snake venom and, most importantly, venom was administered by i.v. route, initiating a very fast procoagulant response (as seen in Table 1). In this context, the use of protocols that better parallel the clinical situation observed during treatment of snakebite accident is crucial before considering GL or other drugs as potential adjuvants for antivenom therapy. Furthermore, the in vivo model here described might be very useful to better understand the contribution of isolated procoagulant and pro-aggregating venom components in coagulopathy caused by whole venom.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Butantan Institute (São Paulo, Brazil) for providing the venom and antibothropic serum used in this study, Dr Paulo Melo for valuable suggestions and Dr Martha Sorenson for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported in part by the International Foundation of Science (Stockholm, Sweden) grant to R.B.Z. (contract F/3156-1). Additional support was provided by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos do Brasil (FINEP) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Carlos Chagas Filho (FAPERJ).

Abbreviations

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- GL

glycyrrhizin

- PT

prothrombin time

- S-2238

H-D-phenylalanyl-L-pipecolyl-L-arginine-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride

References

- AHUJA M.L., VEERARAGHAVAN N., MENON I.G.K. Action of heparin on the venom of Echis carinatus. Nature. 1946;158:878. doi: 10.1038/158878a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURDMANN E.A., WORONIK V., PRADO E.B., ABDULKADER R.C., SALDANHA L.B., BARRETO O.C., MARCONDES M. Snakebite-induced acute renal failure: an experimental model. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;48:82–88. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.48.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARDOSO J.L.C. Bothropic accidents. Mem. Inst. Butantan. 1990;52:43–44. [Google Scholar]

- CASTRO H.C., ZINGALI R.B., ALBUQUERQUE M.G., PUJOL-LUZ M., RODRIGUES C.R. Snake venom thrombin-like enzymes: from reptilase to now. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASTRO K.N.C., CARVALHO A.L.O., ALMEIDA A.P., OLIVEIRA D.B., BORBA H.R, COSTA S.S., ZINGALI R.B. Preliminary in vitro studies on the Marsypianthes chamaedrys (boia-caá) extracts at fibrinoclotting induced by snake venoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:929–932. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(03)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOGDEN E., NEUBERGER J. Alternative medicines and the liver. Liver Int. 2003;23:213–220. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2003.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCISCHETTI I.M., VALENZUELA J.G., RIBEIRO J.M. Anophelin: kinetics and mechanism of thrombin inhibition. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16678–16685. doi: 10.1021/bi991231p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCISCHETTI I.M.B., MONTEIRO R.Q., GUIMARÃES J.A. Identification of glycyrrhizin as a thrombin inhibitor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;235:259–263. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEARD K., O'MALLEY G.F., DART R.C. Antivenom therapy in the Americas. Drugs. 1999;58:5–15. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERBERT J.M., HÉRAULT J.P., BERNAT A., VAN AMSTERDAN R.G.M., VOGEL G.M.T., LORMEAU J.C. Biochemical and pharmacological properties of SANORG 32701. Comparison with the ‘synthetic pentasacharide (SR90107/org 31549)' and standard heparin. Circ. Res. 1996;79:590–600. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUGHTON P.J., OSIBOGUN I.M. Flowering plants used against snakebite. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993;39:1–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUGHTON P.J., SKARI K.P. The effect on blood clotting of some West African plants used against snakebite. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1994;44:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMIGUTI A.S., CARDOSO J.L.C., THEAKSTON I.S., SANO-MARTINS I.S., HUTTON R.A., RUGMAN F.P., WARREL D.A., HAY C.R.M. Coagulopathy and haemorrhage victims of Bothrops jararaca envenoming in Brazil. Toxicon. 1991;29:961–972. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMIGUTI A.S., MATSUNAGA S., SPIR M., SANO-MARTINS I.S., NAHAS L. Alterations of the blood coagulation system after accidental human inoculation by Bothrops jararaca venom. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1986;19:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRSTENANSKY J.L., MAO S.J.T. Antithrombin properties of C-terminus of hirudin using synthetic unsulfated N-alpha-acetyl-hirudin45-65. FEBS Lett. 1987;211:10–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKLAND F.S. Snake venoms and the haemostatic system. Toxicon. 1998;36:1749–1800. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARSH N.A. Snake venoms affecting the haemostatic mechanism – a consideration of their mechanisms, practical applications and biological significance. Blood Coagul. Fibrinol. 1994;5:399–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTZ W. Plants with a reputation against snakebite. Toxicon. 1992;30:1131–1142. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARUYAMA M., KAMIGUTI A.S., CARDOSO J.L.C., SANO-MARTINS I.S., CHUDZINSKI A.M., SANTORO M.L., MORENA P., TOMY S.C., ANTONIO L.C., MIHARA H., KELEN E.M.A. Studies on blood coagulation and fibrinolysis in patients bitten by Bothrops jararaca (jararaca) Thromb. Haemost. 1990;63:449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MENDES-SILVA W., ASSAFIM M., RUTA B., MONTEIRO R.Q., GUIMARÃES J.A., ZINGALI R.B. Antithrombotic effect of Glycyrrhizin, a plant-derived thrombin inhibitor. Thromb. Res. 2003;112:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORS W.B. Plants active against snakebite. Econ. Med. Plant Res. 1991;5:353–373. [Google Scholar]

- MORS W.B., NASCIMENTO M.C., PARENTE J.P., SILVA M.H., MELO P.A., SUAREZ-KURTZ G. Neutralization of lethal and myotoxic activities of South American rattlesnake venom by extracts and constituents of the plant Eclipta prostrata (Asteraceae) Toxicon. 1989;27:1003–1009. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90151-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORS W.B., NASCIMENTO M.C., PEREIRA B.M.R., PEREIRA N.A. Plant natural products active against snake bite – the molecular approach. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:627–642. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAHAS L., KAMIGUTI A.S., BARROS M.A. Thrombin-like and factor X-activator components of Bothrops snake venoms. Thromb. Haemost. 1979;41:314–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAHAS L., KAMIGUTI A.S., RZEPPA H.W., SANO I.S., MATSUNAGA S. Effect of heparin on the coagulant action of snake venoms. Toxicon. 1975;13:457–463. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(75)90175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NGAI P.K., CHANG J.Y. A novel one-step purification of human alpha-thrombin after direct activation of crude prothrombin enriched from plasma. Biochem. J. 1991;280:805–808. doi: 10.1042/bj2800805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONUAGULUCHI G., OKEKE P.C. Preliminary in vitro studies on the antagonistic effects of an ethanolic extract from Diodia scandens on Echis carinatus venom-induced changes in the clotting of human blood. Phytother. Res. 1989;3:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- SANO-MARTINS I.S., SANTORO M.L., MORENA P., SOUSA-E-SILVA M.C., TOMY S.C., ANTONIO L.C., NISHIKAWA A.K., GONCALVES I.L., LARSSON M.H., HAGIWARA M.K., KAMIGUTI A.S. Hematological changes induced by Bothrops jararaca venom in dogs. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1995;28:303–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STUBBS M.T., BODE W. The clot thickens: clues provided by thrombin structure. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMAS L., TYBURN B., BUCHER B., PECOUT F., KETTERLE J., RIEUX D., SMADJA D., GARNIER D., PLUMELLE Y. Prevention of thromboses in human patients with Bothrops lanceolatus envenoming in Martinique: failure of anticoagulants and efficacy of a monospecific antivenom. Research Group on Snake Bites in Martinique. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995;52:419–426. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZINGALI R.B., JANDROT-PERRUS M., GUILLIN M.C., BON C. Bothrojaracin, a new thrombin inhibitor isolated from Bothrops jararaca venom: characterization and mechanism of thrombin inhibition. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10794–10802. doi: 10.1021/bi00091a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]