Abstract

Body odour may provide significant cues about a potential sexual partner's genetic quality, reproductive status and health. In animals, a key trait in a female's choice of sexual partner is male dominance but, to date, this has not been examined in humans. Here, we show that women in the fertile phase of their cycle prefer body odour of males who score high on a questionnaire-based dominance scale (international personality items pool). In accordance with the theory of mixed mating strategies, this preference varies with relationship status, being much stronger in fertile women in stable relationships than in fertile single women.

Keywords: attractiveness, scent, smell, good genes, mate choice, sexual selection

1. Introduction

In many systems, dominance-associated traits have been suggested as honest signals of male genetic quality. Several studies on rodent species have reported preferences for the odour of dominant males (e.g. Mossman & Drickamer 1996; Kruczek 1997; Gosling & Roberts 2001). Odour cues may also play a substantial role in human mate choice. For instance, women prefer the smell of men with low fluctuating asymmetry (Thornhill & Gangestad 1999), which is considered to be a marker of genetic and developmental stability and is an important factor influencing visual attractiveness (Gangestad & Simpson 2000). In addition, humans prefer the scent of opposite-sex individuals with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes that are dissimilar (Wedekind et al. 1995; Wedekind & Füri 1997) or intermediately dissimilar (Jacob et al. 2002) to their own (see also Thornhill et al. 2003). Such preferences might result in more viable offspring (Penn 2002).

It has also been observed that preference for men's scent depends on the menstrual cycle phase of women. In controlled experiments, only the women near peak fertility within their cycle preferred scent of men with low fluctuating asymmetry (Gangestad &Thornhill 1998; Rikowski & Grammer 1999; Thornhill & Gangestad 1999; Thornhill et al. 2003). Similarly, research on facial attractiveness indicates that female preference for visual masculinity (a trait putatively correlated with dominance) varies across the cycle (Penton-Voak et al. 1999) and with partnership status (Little et al. 2002). In this study, we investigated whether women's preference for odour of dominant males also varies cyclically and between single women and those in stable relationships.

2. Methods

(a) Odour stimuli

Forty-eight male students aged between 19 and 27 were asked to complete an 11-item questionnaire on dominance from the international personality items pool (http://ipip.ori.org/ipip/; Goldberg 1999) and to wear cotton pads in their armpits for 24 h. Pads (Premium cosmetic pads, Boots, www.boots.co.uk) were 100% cotton, elliptical in shape, approximately 9×7 cm at their longest axis and held in place using MicroporeTM surgical tape (Boots). The questionnaire was used in its original form and corresponds to the scale ‘Narcissism’ in the widely used California psychological inventory (CPI). Subjects were instructed to avoid spicy and smelly food, alcohol, smoking or using any scented cosmetics on both the evening before and during the day when they were wearing the pads.

(b) Subjects and experimental procedure

Freshly collected pads were presented to 30 female students (mean age 20.6 years) in their follicular phase (days 9 to 15) and to 35 female students (mean age 20.2 years) in other phases of the cycle. The range of days included as falling into the follicular phase (i.e. fertile period) was based on results showing that probability of conception is highest within this ‘fertile window’ (Wilcox et al. 2000). None of the women were using hormonal contraception. Each of them rated the odour of 10 pads for their intensity, sexiness and masculinity using a 7-point scale. The ratings from each woman were converted to z-scores to compute the correlation between male odour and male dominance as measured by the questionnaire. The obtained correlation coefficients showed a normal distribution and, therefore, were compared with random expectation (r=0) using one-sample t-tests. Although our design is between-subjects in nature, this should tend to make our results conservative compared with a within-subjects design.

3. Results

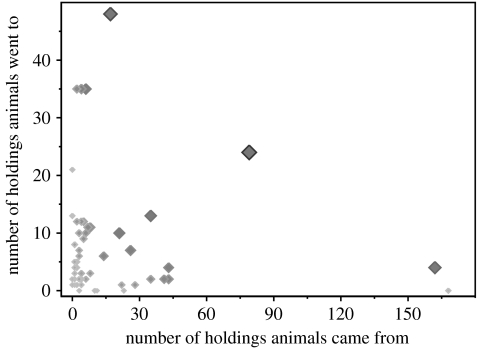

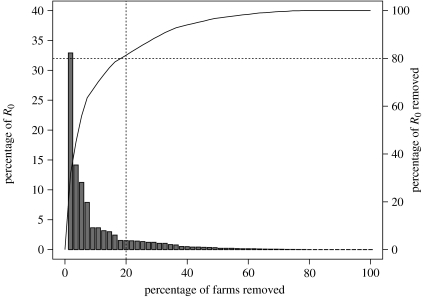

We found a positive correlation between male psychological dominance assessed by the questionnaire and odour sexiness when rated by women in their fertile phase (t29=3.1, p=0.004, mean r=0.20) but not in other phases of their cycle. Subsequently, we tested separately the women who reported to be single and those who were in a heterosexual romantic relationship. A strong association between male odour sexiness and psychological dominance was only found for non-single women in the fertile phase of their menstrual cycle (t12=4.4, p=0.0008, r=0.29; figure 1). There was no significant correlation between male psychological dominance and perceived masculinity of their body odour when rated by single women, regardless of phase of their cycle. In contrast, we found a negative correlation between male dominance and intensity of body odour for both female subsamples (fertile phase of the cycle, t29=2.3, p=0.03, r=−0.13; rest of cycle, t34=3.0, p=0.005, r=−0.18; figure 2). As this effect was observed irrespective of menstrual cycle phase, the shifts in attractiveness of dominant males cannot be explained by variation in odour sensitivity across the cycle (Doty et al. 1981).

Figure 1.

Mean (±s.e.m.) correlation coefficient between the male dominance score and their odour attractiveness rated by single (open bars) or partnered women (grey bars) in the fertile and non-fertile phases of their cycle.

Figure 2.

Correlation between standardized ratings of odour intensity and males' dominance score. (a) Ratings by women in the fertile phase of their cycle, (b) Ratings by women in other phase of their cycle. The two correlations are significant (p<0.05).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that psychological dominance is associated with odour attractiveness. The preference for the odour of dominant men varies with menstrual cycle phase and partnership status of women. The published evidence that men who are visually perceived as dominant are also rated attractive is, however, ambiguous. A positive correlation between attractiveness and perceived dominance was found in one study (Neave et al. 2003), but others have found negative correlations (Perrett et al. 1998; Swaddle & Reierson 2002). None of the studies on facial attractiveness investigated actual dominance in local hierarchies or psychological dominance (i.e. tendency to dominate) of the target subjects. Therefore, it is not clear whether dominant-looking men have a genuine tendency to dominate or whether the attribution of dominance based on facial appearance is misplaced. Evidence for the former suggestion comes from Mueller & Mazur's (1997) study, which found that dominant-looking men reach higher military rank compared with those who look rather submissive. However, even in this case, it remains possible that achieved rank is influenced by dominant appearance without necessarily implying a direct link with psychological dominance.

Although we find that psychological dominance predicts odour attractiveness, we find no significant correlation between dominance and perceived odour masculinity. It has been shown that women rate the smell of androstenone more positively around the time of ovulation (Hummel et al. 1991; Grammer 1993). This substance is a significant constituent of axillary odour and is found in much higher concentrations in men than in women (Gower et al. 1985). More objective measurement of odour masculinity (e.g. levels of 16 androstenes in the axilla) was unfortunately not available in our study. Dominance is stereotypically attributed to more masculine faces (Perrett et al. 1998). However, it is possible that the relationship between dominance and both perceived and measured odour masculinity differs qualitatively from the relationship between dominance and facial masculinity.

There is no common agreement on the interpretation of the association between dominance and attractiveness. Some researchers have suggested that the high mating value of dominant men is a result of their tendency to reaching higher socio-economical status and, therefore, gaining the resources that they may invest in their mate and offspring (Mueller & Mazur 1997). Alternatively, dominance has been suggested to honestly reflect male genetic quality. Tendency to dominate is a risky strategy in competitive encounters and is associated with higher levels of testosterone, which may reduce immunocompetence in various species (Folstad & Karter 1992); dominance could, therefore, reliably indicate male condition. There is also evidence that males of high genetic quality have a tendency for lower parental investment (Waynforth 1998). In response, a mixed mating strategy may have evolved in females: they prefer genetically superior males as short-term or extra-pair sexual partners while, at the same time, they seek males who are more willing to invest in their offspring as long-term or social partners (Reynolds 1996; Penton-Voak et al. 1999; Blomqvist et al. 2002; Foerster et al. 2003). This interpretation is consistent with our findings that women in stable relationships have a strong tendency to prefer the smell of dominant men when in the fertile phase of their cycle, while single women and all women in non-fertile phases lack this preference.

Changes in preference for mate-related traits during the menstrual cycle have been demonstrated repeatedly. Researchers have focused particularly on body odour, symmetry and facial masculinity. The results of four different studies show that the body odour of symmetrical men is rated as more attractive by women in the fertile phase but not other phases of the cycle (Gangestad & Thornhill 1998; Rikowski & Grammer 1999; Thornhill & Gangestad 1999; Thornhill et al. 2003). Several studies also report that women in the fertile phase of their cycle prefer relatively more masculine faces (Penton-Voak et al. 1999; Penton-Voak & Perrett 2000; Johnston et al. 2001). The relative preference for more masculine faces was found also when rated by single women or in a short-term partnership context (Little et al. 2002). All of the above-mentioned studies are congruent with our findings and support the hypothesis about female mixed mating strategies dependent on their cyclical and partnership states.

The proximate mechanism responsible for the correlation between psychological dominance and odour sexiness is unknown. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that emotional state (e.g. fear or happiness) may influence perception of body odour quality (Chen & Haviland-Jones 2000; Ackerl et al. 2002). The higher self-confidence of dominant males may also have an impact on the perceived sexiness of their body odour.

Acknowledgments

We thank all volunteers for their participation in the study, two anonymous referees for their comments on the manuscript and Jindra Jileckova for language corrections. This study was supported in part by the NATO Science Fellowship and the Owen F. Aldis Fund (J.H.) and grant no. 0021620828 awarded to J.F. by the Czech Ministry of Education.

References

- Ackerl K, Atzmueller M, Grammer K. The scent of fear. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2002;23:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist D, Andersson M, Küpper C, Cuthill I.C, Kis J, Lanctot R.B, Sandercock B.K, Székely T, Wallander K, Kempenaers B. Genetic similarity between mates and extra-pair parentage in three species of shorebirds. Nature. 2002;419:613–615. doi: 10.1038/nature01104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Haviland-Jones J. Human olfactory communication of emotion. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2000;91:771–781. doi: 10.2466/pms.2000.91.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty R.L, Snyder P.J, Huggins G.R, Lowry L.D. Endocrine, cardiovascular, and psychological correlates of olfactory sensitivity changes during menstrual-cycle. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1981;98:45–60. doi: 10.1037/h0077755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerster K, Delhey K, Johnsen A, Lifjeld J.T, Kempenaers B. Females increase offspring heterozygosity and fitness through extra-pair matings. Nature. 2003;425:714–717. doi: 10.1038/nature01969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstad I, Karter A.J. Parasites, bright males, and the immunocompetence handicap. Am. Nat. 1992;139:603–622. [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S.W, Simpson J.A. The evolution of human mating: trade-off and strategic pluralism. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000;23:573–644. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x0000337x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangestad S.W, Thornhill R. Menstrual cycle variation in women's preferences for the scent of symmetrical men. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:927–933. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0380. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg L.R. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary I, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F, editors. Personality psychology in Europe. Tilburg University Press; Tilburg, The Netherlands: 1999. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling L.M, Roberts S.C. Scent-marking by male mammals: cheat-proof signals to competitors and mates. Adv. Stud. Behav. 2001;30:169–217. [Google Scholar]

- Gower D.B, Bird S, Sharma P, House F.R. Axillary 5 alpha-androst-16-en-3-one in men and women: relationships with olfactory acuity to odorous 16-androstenes. Experientia. 1985;41:1134–1136. doi: 10.1007/BF01951694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammer K. 5-α-androst-16en-3α-on: a male pheromone? A brief report. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1993;14:201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Gollisch R, Wildt G, Kobal G. Changes in olfactory perception during the menstrual cycle. Experientia. 1991;47:712–715. doi: 10.1007/BF01958823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S, McClintock M.K, Zelano B, Ober C. Paternally inherited HLA alleles are associated with women's choice of male odor. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:175–179. doi: 10.1038/ng830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston V.S, Hagel R, Franklin M, Fink B, Grammer K. Male facial attractiveness. Evidence for hormone-mediated adaptive design. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2001;22:251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek M. Male rank and female choice in the bank vole, Clethrionomys glareolus. Behav. Processes. 1997;40:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(97)00785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Jones B.C, Penton-Voak I.S, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Partnership status and the temporal context of relationships influence human female preferences for sexual dimorphism in male face shape. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:1095–1100. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1984. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman C.A, Drickamer L.C. Odor preferences of female house mice (Mus domesticus) in seminatural enclosures. J. Comp. Psychol. 1996;110:131–138. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.110.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller U, Mazur A. Facial dominance in Homo sapiens as honest signaling of male quality. Behav. Ecol. 1997;8:569–579. [Google Scholar]

- Neave N, Laing S, Fink B, Manning J.T. Second to fourth digit ratio, testosterone and perceived male dominance. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270:2167–2172. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2502. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn D.J. The scent of genetic compatibility: sexual selection and the major histocompatibility complex. Ethology. 2002;108:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Perrett D.I. Female preference for male faces changes cyclically: further evidence. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2000;21:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Perrett D.I, Castles D.L, Kobayashi T, Burt D.M, Murray L.K, Minamisawa R. Menstrual cycle alters face preference. Nature. 1999;399:741–742. doi: 10.1038/21557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrett D.I, Lee K.J, Penton-Voak I.S, Rowland D, Yoshikawa S, Burt D.M, Henzi S.P, Castles D.L, Akamatsu S. Effects of sexual dimorphism on facial attractiveness. Nature. 1998;394:884–887. doi: 10.1038/29772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.D. Animal breeding systems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996;11:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)81045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikowski A, Grammer K. Human body odour, symmetry and attractiveness. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:869–874. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0717. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaddle J.P, Reierson G.W. Testosterone increases perceived dominance but not attractiveness in human males. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:2285–2289. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2165. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad S.W. The scent of symmetry: a human sex pheromone that signals fitness? Evol. Hum. Behav. 1999;20:175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Thornhill R, Gangestad S.W, Miller R, Scheyd G, McCollough J.K, Franklin M. Major histocompatibility complex genes, symmetry, and body scent attractiveness in men and women. Behav. Ecol. 2003;14:668–678. [Google Scholar]

- Waynforth D. Fluctuating asymmetry and human male life-history traits in rural Belize. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:1497–1501. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0463. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind C, Füri S. Body odour preferences in men and women: do they aim for specific MHC combinations or simply heterozygosity? Proc. R. Soc. B. 1997;264:1471–1479. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0204. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind C, Seebeck T, Bettens F, Paepke A.J. MHC-dependent mate preference in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1995;260:245–249. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A.J, Dunson D, Baird D.D. The timing of the ‘fertile window’ in the menstrual cycle: day specific estimates from a prospective study. Br. Med. J. 2000;321:1259–1262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]