Abstract

Energetically costly behaviours, such as flight, push physiological systems to their limits requiring metabolic rates (MR) that are highly elevated above the resting MR (RMR). Both RMR and MR during exercise (e.g. flight or running) in birds and mammals scale allometrically, although there is little consensus about the underlying mechanisms or the scaling relationships themselves. Even less is known about the allometric scaling of RMR and MR during exercise in insects. We analysed data on the resting and flight MR (FMR) of over 50 insect species that fly to determine whether RMR and FMR scale allometrically. RMR scaled with body mass to the power of 0.66 (M0.66), whereas FMR scaled with M1.10. Further analysis suggested that FMR scaled with two separate relationships; insects weighing less than 10 mg had fourfold lower FMR than predicted from the scaling of FMR in insects weighing more than 10 mg, although both groups scaled with M0.86. The scaling exponents of RMR and FMR in insects were not significantly different from those of birds and mammals, suggesting that they might be determined by similar factors. We argue that low FMR in small insects suggests these insects may be making considerable energy savings during flight, which could be extremely important for the physiology and evolution of insect flight.

Keywords: resting metabolic rate, flight metabolic rate, insect, allometric scaling

1. Introduction

Insects were the first animals to evolve flight and they remain unsurpassed in their manoeuvrability, performing spectacular aerial acrobatics. Yet despite their flight prowess, relatively little is understood about the physiological basis of insect flight. The demands on active metabolism during flight may be particularly acute as flapping flight is an extremely energetically expensive form of locomotion. Insect flight muscles are among the most metabolically active of tissues known (Dudley 2000). Within the insects, there is considerable variation in flight performance and many species are flightless. Insects are also extremely diverse in terms of their size and shape, much more so than birds or mammals.

During exercise, such as flight, the metabolic rates (MR) of animals are dominated by the activity of skeletal muscles, whereas at rest their metabolic rate is likely to be dominated by other tissues such as the nervous system and excretory organs (Weibel 2002). Therefore, during flight, insect metabolism is likely to be dominated by the energy consumption of the flight muscles. Although there is no current theory relating metabolic rate at rest (RMR) to that during exercise (Weibel et al. 2004), several studies on birds and mammals have linked the two (Bishop 1999; Darveau et al. 2002).

The RMR of insects is likely to scale allometrically—that is, scale with some power of body mass (Reinhold 1999; Addo-Bediako et al. 2002). Such scaling has also been observed in arthropods (e.g. chelicerates) as well as in vertebrates, including fishes, birds and mammals (Bishop 1999; Lighton et al. 2001; White & Seymour 2003; Bokma 2004). In these studies RMR correlated positively with body mass, whereas mass-specific RMR (sRMR) correlated negatively with body mass. Although few studies have measured MR during exercise, studies of mammals and birds (Taylor et al. 1981; Bishop 1999; Bundle et al. 1999; Weibel et al. 2004) suggest that this also correlates positively with body mass, whereas the mass-specific MR (sMR) during exercise correlates negatively with body mass. Since the majority of insects are ectothermic at rest and have a relatively small body mass, their RMR is likely to be extremely low—much lower than that of birds and mammals. During flight, the highly elevated MR of insects will produce even higher sMR, which may have significantly effects upon flight physiology.

The allometric scaling relationships reported in birds and mammals, and even the underlying basis of these relationships, remain controversial (Dodds et al. 2001; Weibel 2001; Niven 2004). Several recent studies have suggested that the scaling of RMR in mammals may be linked to nutrient supply networks (West et al. 1997). However, it is clear from studies of allometric scaling in birds and mammals that current theories explaining RMR scaling are unlikely to explain the scaling of MR during exercise (Weibel et al. 2004). The insect tracheal system may be considered analogous to the supply networks in mammals and birds. Therefore, examination of allometric scaling relationships for RMR and metabolic rate in flight (FMR) in insects may not only provide insights into the evolution and adaptation of insect metabolism for flight but also, more generally, into interactions between RMR and MR during exercise.

2. Materials and methods

See Electronic Appendix section A.

3. Results

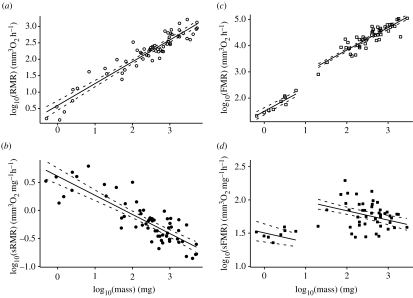

RMR of 61 insect species from seven orders were obtained from published data, covering more than three orders of magnitude in body mass (see Electronic Appendix section A). Insect RMR scaled positively with body mass (figure 1a: RMR=4.14M0.66; F1,59=544.9, p<0.0001; 95% CI of exponent: 0.600, 0.713 and r2=0.90), whereas sRMR scaled negatively with body mass (figure 1b: sRMR=4.14M−0.34; F1,59=148.5, p<0.0001; 95% CI: −0.343, −0.287 and r2=0.72). The negative exponent indicated that an equivalent amount of tissue is more energetically expensive in smaller insects.

Figure 1.

Allometric scaling of resting (RMR) and flight metabolic rates (FMR) with insect body mass. Double-log plots of body mass versus (a) RMR, (b) mass-specific RMR (sRMR), (c) FMR and (d) mass-specific FMR (sFMR). Lines are least-squares regression lines (a), (b) and ANCOVA lines for small (less than 10 mg) and large (greater than 10 mg) insects (c), (d). Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence limits.

We obtained FMR values for 56 insect species from six orders from previously published data (see Electronic Appendix section A). Although measurements were taken from hovering or flying insects, this is unlikely to significantly affect the FMR, which is similar over a range of moderate flight speeds (Ellington et al. 1990). Both FMR and mass-specific FMR (sFMR) of the entire dataset scaled positively with body mass (FMR=35.08M1.07, F1,54=1108, p<0.0001, 95% CI: 1.010, 1.138; sFMR=35.08M0.07, F1,54=5.22, p=0.026 and 95% CI: 0.009, 0.138), and body mass explained much of the variation in FMR (r2=0.95) but little of the variation in sFMR (r2=0.09). Surprisingly, the positive scaling exponent of sFMR suggested that an equivalent amount of tissue was more energetically expensive in larger insects.

This seems unlikely, as sMR at rest and during exercise correlated negatively with body mass in several other groups of animals (e.g. Taylor et al. 1981; Bishop 1999). Instead, the overall scaling relationships of FMR and sFMR may be composed of several separate allometric scaling relationships. Two distinct clusters of points were clearly visible (figure 1c,d), suggesting that this might be the case. One cluster contained insects with small body mass (less than 10 mg), whereas the other contained larger species (greater than 10 mg). We employed ANCOVAs to test whether there were significant differences between these two clusters in the exponent and intercept of the scaling relationship. While the exponents of the power law relationship for FMR and sFMR were not significantly different for small and large insects (F1,53=0.47, p=0.50 and F1,53=0.47, p=0.50, respectively), they had significantly different intercepts (F1,50=15.18, p<0.0003 and F1,50=15.18, p<0.0003; figure 1c,d, respectively). The relationship for large insects was FMR=129.94M0.87, whereas that for small insects was FMR=31.62M0.87 (95% CI: 0.736, 0.983; r2=0.96), suggesting that the FMR of smaller insects was approximately fourfold lower than predicted from larger insects (figure 1c). Likewise, the relationship for large insects was sFMR=129.94M−0.14, whereas that for small insects was sFMR=31.62M−0.14 (95% CI: −0.264, −0.017; figure 1d). In contrast to the analyses of the entire dataset, this suggests that within each group an equivalent amount of tissue was more energetically expensive in smaller insects and explained a greater proportion of the variation (r2=0.29).

4. Discussion

Two alternative theoretical relationships, M3/4 and M2/3, have been suggested to describe the allometric scaling of RMR in mammals and birds (Rubner 1883; Kleiber 1932; Dodds et al. 2001), with the three-quarter-power scaling proposed as a universal scaling law (West et al. 1997). The scaling exponent we obtained for insect RMR, 0.66±0.03 (least-squares regression coefficient±s.e.), was significantly different from M3/4 but not from M2/3 (t-test on means: t=3.30, p=0.0016 and t=0.46, p=0.65, respectively, and d.f.=59 for both). This raises the possibility that, even if a three-quarter-power relationship describes the allometric scaling of RMR in mammals, it may not be a universal scaling law. Our scaling relationship for RMR in insects is closer to the two-third-power scaling originally proposed by Rubner (1883); however, the 0.69±0.03 scaling exponent obtained by reduced major axis regression lies between the two theoretical exponents (see Electronic Appendix section A). Previous studies using least-squares regression have obtained allometric scaling relationships for teleost fishes (0.72; Bokma 2004), birds and mammals (0.73; Bishop 1999) and mammals (0.74; Savage et al. 2004) whose exponents are significantly different from the 0.66 exponent we obtained for insect RMR, although the 0.68 exponent for mammals obtained by White & Seymour (2003) was not significantly different. The consistent differences between the experimentally observed and theoretical exponents raise the possibility that a single relationship may not be sufficient to describe metabolic scaling in animals.

Previous studies on insects, which assessed flying and non-flying species separately, have also suggested that RMR may not scale with M3/4; RMR∝M0.70 for flying insects and RMR∝M0.86 or M0.82 for non-flying insects (Lighton et al. 2001; Addo-Bediako et al. 2002). The exponent for flying insects obtained by Addo-Bediako et al. (2002) was not significantly different from the exponent obtained in this study, whereas both exponents for non-flying insects were significantly different. There may also be substantial differences in RMR related to differing phylogeny among insects. Comparative analysis by independent contrasts may produce different scaling relationships from those obtained without taking phylogeny into account (Harvey & Pagel 1991). However, phylogenies have not been established for many insect species and the use of incorrect phylogenies may produce erroneous allometric scaling relationships (Symonds & Elgar 2002).

In our analyses of the entire dataset, FMR and sFMR both correlated positively with body mass, suggesting that an equivalent amount of tissue is more expensive in larger insects. The scaling exponents of FMR and sFMR (M0.86 and M−0.14, respectively) after allowing for clusters of large and small insects are different from those of RMR and sRMR. Mammals and birds also show allometric scaling of MR during exercise close to M0.86 (e.g. M0.87 in running mammals and M0.88 in flying birds) that is significantly larger than their RMR scaling (Taylor et al. 1981; Bishop 1999; Weibel et al. 2004). Although FMR is not necessarily equivalent to maximal MR in insects (Roberts et al. 2004), this suggests that MR during exercise scales allometrically in a similar way in insects, birds and mammals.

The FMR intercept for large insects was approximately 32-fold higher than that of the same insects at rest, whereas for small insects it was approximately eightfold higher. The reduction of both FMR and sFMR of small insects relative to their predicted values from larger insects suggests that they are expending considerably less energy during flight. Indeed, the fruitfly, Drosophila melanogaster, has a similar sFMR to the desert locust, Schistocerca gregaria, which weighs over 1000 times as much. Although tethering may have artefactually reduced the estimates of FMR and sFMR during experiments in which flight force was not monitored, it is unlikely to explain the low measurements in small insects fully, unless its effects have been severely underestimated (see Electronic Appendix section B).

FMR is primarily determined by the contraction of synchronous or asynchronous flight muscles; nevertheless, flight muscles constitute a relatively constant proportion of body mass in insects (Greenewalt 1962). Moreover, flight muscle efficiency appears to be independent of both insect size and muscle type (synchronous or asynchronous; Lehmann 2001), suggesting that the amount or efficiency of muscle cannot account for the observed differences in FMR between small and large insects.

The wing beat frequency may account for the low FMR of small insects. The wing beat frequency of Drosophilid flies is unusually slow in comparison with their body mass (Greenewalt 1962), which may save energy during flight. However, additional experiments are necessary to further define the allometric scaling of insect FMR before the precise mechanisms can be addressed. While partitioning of the data reveals differences in FMR scaling between small and large insects, partitioning according to phylogeny may reveal differences among insect orders that could contribute to the scaling relationships outlined here. Measurements of FMR from insects of between 10 and 100 mg are crucial to obtain a better estimate of FMR scaling. In particular, there are almost no FMR measurements for larger Dipterans, such as Musca domestica, or small flying insects from orders other than the Diptera. Such measurements will be essential to understand the impact of allometric scaling of FMR on the physiology and evolution of insect flight.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charlie Ellington, Gerda Nolan and three anonymous referees for comments on a previous draft of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant to S. B. Laughlin from the BBSRC.

Footnotes

Present address: Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK.

Supplementary Material

References

- Addo-Bediako A, Chown S.L, Gaston K.J. Metabolic cold adaptation in insects: a large-scale perspective. Funct. Ecol. 2002;16:332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop C.M. The maximum oxygen consumption and aerobic scope of birds and mammals: getting to the heart of the matter. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:2275–2281. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0919. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokma F. Evidence against universal metabolic allometry. Funct. Ecol. 2004;18:184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bundle M.W, Hoppeler H, Vock R, Tester J.M, Weyand P.G. High metabolic rates in running birds. Nature. 1999;397:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Darveau C.-A, Suarez R.K, Andrews R.D, Hochachka P.W. Allometric cascades as a unifying principle of body mass effects on metabolism. Nature. 2002;417:166–170. doi: 10.1038/417166a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.S, Rothman D.H, Weitz J.S. Re-examination of the ‘3/4-law’ of metabolism. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;209:9–27. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R. Princeton University Press; 2000. The biomechanics of insect flight: form, function, evolution. [Google Scholar]

- Ellington C.P, Machin K.E, Casey T.M. Oxygen consumption of bumblebees in forward flight. Nature. 1990;347:472–473. [Google Scholar]

- Greenewalt C.H. Dimensional relationships for flying animals. Smithson. Misc. Collect. 1962;144:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.H, Pagel M.D. OUP; Oxford: 1991. The comparative method in evolutionary biology. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiber M. Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia. 1932;6:315–353. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann F.-O. The efficiency of aerodynamic force production in Drosophila. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;131:77–88. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighton J.R.B, Brownell P.H, Joos B, Turner R.J. Low metabolic rate in scorpions: implications for population biomass and cannibalism. J. Exp. Biol. 2001;204:607–613. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niven J.E. Fishing for answers. J. Exp. Biol. 2004;20:iv. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold K. Energetically costly behaviour and the evolution of resting metabolic rate in insects. Funct. Ecol. 1999;13:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S.P, Harrison J.F, Dudley R. Allometry of kinematics and energetics in carpenter bees (Xylocopa varipuncta) hovering in variable-density gases. J. Exp. Biol. 2004;207:993–1004. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubner M. Ueber den Einfluss der Körpergrösse auf Stoff-und Kraftwechsel. Z. Biol. 1883;19:535–562. [Google Scholar]

- Savage V.M, Gillooly J.F, Woodruff W.H, West G.B, Allen A.P, Enquist B.J, Brown J.H. The predominance of quarter-power scaling in biology. Funct. Ecol. 2004;18:257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Symonds M.R.E, Elgar M.A. Phylogeny affects estimation of metabolic scaling in mammals. Evolution. 2002;56:2330–2333. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C.R, Maloiy G.M.O, Weibel E.R, Lungman V.A, Kamau J.M.Z, Seeherman H.J, Heglund N.C. Design of the mammalian respiratory system 3. Scaling maximum aerobic capacity to body-mass: wild and domestic animals. Respir. Physiol. 1981;44:25–37. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(81)90075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel E.R. The pitfalls of power laws. Nature. 2002;417:131–132. doi: 10.1038/417131a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel E.R, Bacigalupe L.D, Schmitt B, Hoppeler H. Allometric scaling of maximal metabolic rate in mammals: muscle aerobic capacity as a determinant factor. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2004;140:115–132. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West G.B, Brown J.H, Enquist B.J. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science. 1997;276:122–126. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C.R, Seymour R.S. Mammalian basal metabolic rate is proportional to body mass2/3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4046–4049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.