Abstract

Typically during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection, a nearly homogeneous viral population first emerges and then diversifies over time due to selective forces that are poorly understood. To identify these forces, we conducted an intensive longitudinal study of viral genetic changes and T-cell immunity in one subject at ≤17 time points during his first 3 years of infection, and in his infecting partner near the time of transmission. Autologous peptides covering amino acid sites inferred to be under positive selection were powerful for identifying HIV-1-specific cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes. Positive selection and mutations resulting in escape from CTLs occurred across the viral proteome. We detected 25 CTL epitopes, including 14 previously unreported. Seven new epitopes mapped to the viral Env protein, emphasizing Env as a major target of CTLs. One-third of the selected sites were associated with epitopic mutational escapes from CTLs. Most of these resulted from replacement with amino acids found at low database frequency. Another one-third represented acquisition of amino acids found at high database frequency, suggesting potential reversions of CTL epitopic sites recognized by the immune system of the transmitting partner and mutation toward improved viral fitness in the absence of immune targeting within the recipient. A majority of the remaining selected sites occurred in the envelope protein and may have been subjected to humoral immune selection. Hence, a majority of the amino acids undergoing selection in this subject appeared to result from fitness-balanced CTL selection, confirming CTLs as a dominant selective force in HIV-1 infection.

Understanding the complexities of human immune responses and mechanisms by which human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) evades those responses will assist the development of effective vaccines. Adaptive immune responses mediated by helper (37, 44, 49) and cytotoxic T cells (8, 30, 42), as well as humoral immune responses mediated by antibodies (39), are involved in host defense against and control of HIV-1 infection. HIV-1 evolution thwarts these activities by accumulation of mutations that prevent recognition by these immune effectors. Indeed, selective escape from CD8+ T-cell responses has been reported to be a major driving force of HIV-1 sequence diversity over portions of the region of the viral genome that encodes protein, the viral proteome (3, 24).

In vitro studies indicate that cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) can both effectively kill HIV-1-infected cells and inhibit viral replication through cytolytic and noncytolytic mechanisms (57). Studies of simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys showed that depletion of CTL during primary infection led to the loss of initial control of viral replication and that depletion of CTL during chronic infection was associated with a rapid and marked increase in viremia (50). In humans, CTL responses have been associated with the decline of HIV-1 viremia following primary infection (8, 30). CTL responses are detectable in most study subjects, and responses to all nine HIV-1 proteins have been found to occur (2, 10, 15). Nef, Gag, and Pol (2, 7, 45) are reported to be recognized more frequently than Env, perhaps as a result of exceptionally high variability in Env (6, 15).

Despite these responses, adaptive host immunity is not able to clear HIV-1 infection, and numerous studies implicate CTL escape as an important mechanism for HIV-1 evasion. CTL responses to HIV-1 appear to select for escape mutants during both acute (9, 11, 24, 46) and, perhaps to a more limited extent (14, 27), chronic infection (4, 5, 17, 20, 55). In vitro studies demonstrate that incomplete HIV-1 suppression by CTL can result in rapid emergence of immune escape mutants (56). Viral adaptation to HLA-restricted CTL responses at the population level has also been inferred (25, 33, 34, 40, 61). Furthermore, recent reports indicate that reversion of CTL escape mutations can occur upon transmission to a new host (4, 34), likely reflecting recovery of a viral fitness cost exacted by amino acid substitutions that resulted in immune escape (16, 19, 24).

In an effort to affirm the aforementioned findings and to comprehensively examine the relationship between CTL responses and overall positive selective pressure acting throughout the HIV-1 proteome, we intensively studied the first 3 years of HIV-1 infection in an antiretroviral-therapy-naïve subject (PIC1362). Longitudinal viral genome or subgenome sequences were determined from plasma virions. Using computational methods, we identified sites potentially having experienced positive selection throughout the HIV-1 proteome. In addition, over the same time frame as viral sequencing was done, overlapping peptides representing the amino acid sequences of the entire HIV-1 proteome were tested for their ability to elicit CD8+ gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-secreting-T-cell responses. Our studies demonstrate that CTL responses are a major contributor to the positive selection shaping the viral population during the early years of HIV-1 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects and specimens.

Clinical progression and virologic and preliminary immunologic characterizations of PIC1362 have been reported previously (11). His plasma viral loads were over 104 copies/ml, his CD4+ T-cell counts fluctuated around 103 cells/μl, and no antiretroviral therapy was administered throughout the course of study (Fig. 1A). The subject's class I HLA alleles, determined by sequence-specific primer PCR (11), are A*0201, A*2501, B*1801, B*5101, Cw*0102, and Cw*1203. Plasma samples were obtained from 15 time points: 8, 22, 50, 76, 113, 155, 190, 344, 414, 491, 581, 667, 769, 826, and 1,035 days after onset of acute symptoms of primary HIV-1 infection. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were obtained from 17 time points: 8, 22, 29, 34, 50, 155, 190, 259, 304, 344, 491, 496, 680, 769, 826, 829, and 1,035 days after the onset of acute symptoms.

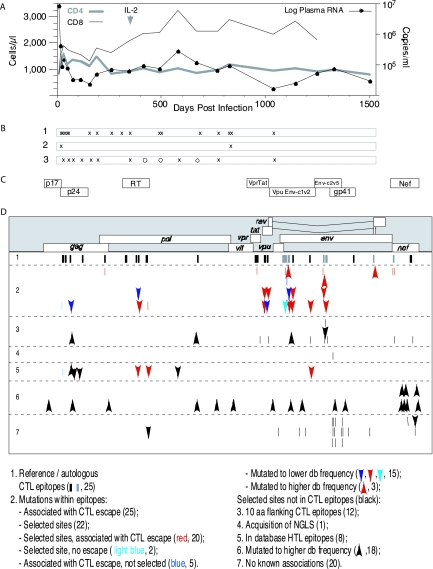

FIG. 1.

Clinical progression, venipuncture time points, and positive selection following acute HIV-1 infection in PIC1362. (A) Longitudinal viral load and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts. The arrow indicates the single treatment of interleukin 2 (IL-2) taken by the subject. (B) Time points of IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis (row 1) and full-length (row 2) as well as subgenomic (row 3) sequencing, indicated by X's. Open circles indicate additional time points at which Gag p17 and p24 coding regions were sequenced. (C) Coding elements of the viral genome encompassed by targeted gene sequencing. (D) Codon positions of amino acids potentially under positive selection in the HIV-1 genome and their relationships to CTL responses and other potential selective forces. Reference epitopes were identified using peptides derived from HIV-1 subtype B lab strains or consensus sequences. Autologous epitopes were identified using peptides whose amino acid sequences were derived from the viral gene sequences of the subject. The numbers in parentheses correspond to the numbers of epitopes or amino acid sites within each category. Arrows pointing downward show sites mutated to a lower database (db) frequency, meaning the amino acid at a particular position had a database frequency of >50% during the initial infection and later mutated to a state with a database frequency of less than 50% and less than half of the database frequency of the initial state. Arrows pointing upward show sites mutated to a higher database frequency, meaning the amino acid at a particular position had a database frequency of <50% during the initial infection and later mutated to a state with a database frequency of more than 50% and at least twofold higher than the database frequency of the initial state. NGLS, N-linked glycosylation site.

Plasma and PBMC samples were obtained from his partner, PIC1365, at 23 days as well as approximately 4 years after onset of acute symptoms of HIV-1 infection in PIC1362. PIC1365 had been HIV-1 positive for ∼10 years at the time of the transmission, and his class I HLA alleles were determined to be A*0101, A*0201, B*0801, B*5001/5004, Cw*0602, and Cw*0701.

Amplification and sequencing of viral genomes and fragments.

RNA was purified from plasma virions by use of a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Viral RNA was reverse transcribed and targeted gene regions amplified by nested PCR as previously described (36). Primers used in this study and their corresponding products are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

For half- and full-length viral genome cDNA synthesis, a mixture of 34 μl viral RNA, 40 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), and 80 pmol of 24-mer oligo(dT) primers was preincubated for 5 min at 65°C and then incubated for 1.5 h at 45°C with prewarmed 40 U RNase inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), 800 U SuperscriptII, and 5X First-Strand buffer (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The mixture was supplemented with 400 U of SuperscriptII and incubated for another 1.5 h. The resulting cDNA was treated with 4 U RNase H (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) for 30 min prior to PCR amplification. An Expand long-template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was then used for amplification by following the manufacturer's recommendations for buffer system 1. Hot-start PCR was carried out using paraffin in 0.5-ml thin-walled tubes in a DNA engine thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) under the following conditions: 2 min at 94°C; 10 cycles of 10 s at 94°C and 8.5 min at 68°C; and 20 cycles of 10 s at 94°C and 8.5 min at 68°C (with the extension step incremented by 20 s per cycle).

Targeted-gene PCR products were cloned into the TOPO TA vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and selected for sequencing as described previously (52) to avoid template resampling (35). PCR products from half- and full-length genome amplifications were gel purified, cloned into the pCR-XL-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), and sequenced by primer walking. To avoid template resampling, only one clone from each PCR was sequenced. Sequencing primers were designed for every 600 to 700 bases from HIV-1 clade B alignments, with a total of 32 primers. Due to viral variation, sequencing primers often had to be redesigned to amplify specific sequences. Sequences were determined with an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and edited using SEQUENCHER, version 3.0 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI).

Synthetic peptides and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays.

By use of selected reference strains and consensus sequences as guides, 769 peptides spanning the entire HIV-1 subtype B proteome were synthesized for enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays. Env peptides (212 11- to 15-mers) were based on HIV-1MN; Gag (122 15-mer), Pol (248 12- to 15-mer), Tat (23 15-mer), and Nef (49 15-mer) peptides were based on HIV-1HXB2; and Vpr (22 15-mer), Rev (27 15-mer), Vif (47 15-mer), and Vpu (six 9-mer and 13 15-mer) peptides were based on the 2001 HIV-1 subtype B consensus sequence (32). In addition, to cover the differences between the major variants of the viruses infecting PIC1362 and the initial testing peptide panel, for Nef and variable loops of Env, a total of 91 additional peptides (41 Env 15-mer peptides [20 for V1/V2, 8 for V3, 8 for V4, and 5 for V5] and 50 Nef 15-mer peptides) were derived from autologous sequences from plasma viruses sequenced 8 days after onset of symptoms. Last, we synthesized 78 additional autologous 15-mer peptides whose sequences corresponded to 29 selected sites outside Nef and the variable regions of Env but were not included within the initial testing peptide panels. All 15-mers overlapped by 11 amino acids. For ELISPOT assay-positive 15-mers, shorter peptides were synthesized to define optimal CTL epitopes. All peptides used in this study are provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Peptides were synthesized by the Biotechnology Center at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Synpep (Dublin, CA), or kindly provided by the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays and determination of 50% effective concentration (EC50), the effective peptide concentration eliciting 50% of the peak IFN-γ response in the ELISPOT assay, were performed as previously described (10).

Estimation of diversifying selection.

Amino acid sites under diversifying selection, in which mutations to other amino acids are advantageous, are indicated by an excessive nonsynonymous-substitution distance compared to the synonymous-substitution distance within the codon (e.g., see references 18 and 48). Mutations within a codon that change the encoded amino acid are referred to as nonsynonymous, whereas mutations that do not change the encoded amino acid are referred to as synonymous. The number of nonsynonymous or synonymous changes per potential nonsynonymous or synonymous site is referred to as the nonsynonymous or synonymous distance (dn and ds, respectively). The ratio dn/ds, or ω, has been used to assess selection (26). Generally speaking, ω of >1 indicates diversifying selection. For this analysis, the program PAUP* (54) was used to generate maximum-likelihood trees. CODEML, from a package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood (PAML) (58, 59), was then used to identify sites potentially under diversifying selection. The latter program employs codon-based models that allow for variable selection intensities among sites within protein-coding DNA sequences. By estimating dn and ds from the sample's phylogeny, the program can identify individual sites experiencing diversifying selection, i.e., those with ω of >1. The sequence data were fit to a model (M7) in which all sites belonged to a category in which ω was beta-distributed and bound between 0 and 1 and to a model (M8) in which a fraction of sites belonged to a category in which ω was beta-distributed and bound between 0 and 1, with the remaining sites belonging to a category with a freely estimated ω value. A significantly better fit of M8 than of M7 (by a likelihood ratio test with 2 degrees of freedom) and a freely estimated ω value greater than 1 were taken as evidence of diversifying selection. Next, if a codon's posterior probability of belonging to the category of codons with ω of >1 was greater than 99%, it was considered to have experienced diversifying selection.

Estimation of directional selection.

Amino acid sites experiencing directional selection, in which mutation to one particular amino acid is advantageous, are inferred when a mutant accumulates in the population faster than expected due to random drift. Suppose the frequency of a mutant at a site increases from f1 to f2 in time t1 to t2. A simulation program was written to determine if the frequency increase was likely due to random genetic drift. One thousand simulations of random genetic drift were repeated with a population of n individuals, with the parents being randomly sampled with replacement each generation. The effective population size of HIV-1 within a chronically infected individual has been estimated to be on the order of 103 (1, 31, 51, 53); thus, n was set to 1,000. The probability that an allele increases in frequency from f1 to f2 from time t1 to t2 by random genetic drift, P(time = t2 − t1 | finitial = f1, ffinal = f2, n = 1,000), can thus be estimated. If P is >5%, the frequency increase can be explained by random genetic drift. Otherwise, the mutated site is considered to be potentially under directional selection. The generation time of HIV-1 has been estimated to be 2.0 days (38); thus, the time interval between t1 and t2 can be converted from days to generations.

Longitudinal sequence alignments of PIC1362 were screened for amino acid sites with mutations that had increasing frequencies over time. For a mutant, t1 was taken as the time point just before the observation of the mutation and f1 was set at 1/n1, with n1 being the sample size at t1. If the sequences in the data set were not all in the mutant form at the last time point, t2 was taken as the last time point, and the observed last time point frequency of the mutant was used as f2. Otherwise, the time point after which the mutant frequency remained at 100% in the data set was used as t2 and f2 was set at (n2 − 1)/n2, with n2 being the sample size at t2.

Estimation of selection coefficient.

We assumed that HIV-1 would behave as a haploid organism and that its evolution could be described adequately by a discrete-generations model due to fast turnover (47). Therefore, the effect of selection can be described by log(pt/qt) = log(p0/q0) + t × log(1 + s) (22), where p0 is the initial frequency of the advantageous mutant and q0 is the initial frequency of the original amino acid. After t generations, the frequency of the advantageous mutant becomes pt, and the frequency of the original amino acid becomes qt (note that p0 + q0 = 1 and pt + qt = 1). When multiple mutant forms were observed for an epitope, all of the mutants were treated equally: p0 and pt are the sums of the frequencies of all of the mutants at generation 0 and generation t, respectively. For each epitope or site of interest, the selection coefficient, s, was estimated from longitudinal data from the time that any mutant was observed until the time at which no wild type was observed. Estimation of s was conducted with nonlinear regression using SAS version 9 PROC MODEL. s was assumed to be constant over all observation times. Profile likelihood was used to obtain s for each case where two or more data points were available for analysis.

Calculation of the database representation of each amino acid at positions of interest.

The database frequencies of amino acids at each position were calculated using a collection of subtype B HIV-1 sequences chosen at random, one sequence per individual, from the HIV-1 sequence database (28, 32): 139 sequences for p17, 150 for p24, 130 for protease, 87 for reverse transcriptase (RT), 75 for IN, 155 for Vpr, 94 for Tat, 91 for Vpu, 111 for gp160, and 226 for Nef.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers DQ853426 to DQ854622.

RESULTS

Amino acid sites potentially having experienced diversifying or directional selection.

Viral sequences were derived from 10 5′ and 3′ half genomes from day 8 and from 10 whole genomes from day 826 after the onset of acute symptoms of HIV-1 infection. Subgenomic-fragment sequences encompassing 55% of the viral genome were obtained and analyzed. These included fragments from gag-p17, gag-p24, pol-RT, vpr-tat, vpu-V2(env), env-C2-V5, env-gp41, and nef from an additional 10 time points (days 22, 50, 76, 113, 155, 190, 344, 581, 769, and 1035), as well as a gag-p24 fragment from days 414 and 491 and a gag-p17 fragment from days 491 and 667 (Fig. 1B). An average of 13 sequences per gene fragment per time point was available for analysis.

One thousand sixty three amino acid sites across the viral proteome exhibited polymorphism within this data set. We used computational methods to identify sites among them that potentially had experienced diversifying selection or directional selection (see Materials and Methods). We found 39 sites undergoing diversifying selection and 34 others undergoing directional selection. Of the total of 73 sites, 36 were in Env, 14 in Nef, 8 in Pol, 5 in Gag, a total of 10 in Vif, Vpr, Tat, and Vpu, and none in Rev (Fig. 1C). Table 1 summarizes all of the selected amino acid sites and their associations with known selective forces.

TABLE 1.

Summary of selected amino acid sites

| Type of selection | No. (%) of selected sites

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Within CTL epitopes | Outside CTL epitopes

|

|||||||

| Within 10 aa of CTL epitopes | In known HTL epitopes | Resulted in acquisition of NGLSa | Mutated to higher database frequencyb | Otherc

|

Total | ||||

| Within Env | Outside Env | ||||||||

| Diversifying | 39 | 15 (38) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | 12 (31) | 2 (5) | 24 (62) |

| Directional | 34 | 7 (21) | 4 (12) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 15 (44) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) | 27 (79) |

| Total | 73 | 22 (30) | 12 (16) | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 18 (25) | 15 (21) | 5 (7) | 51 (70) |

NGLS, N-linked glycosylation site.

The amino acid at a particular position had a database frequency of <50% during the initial infection and later mutated to a state with a database frequency of more than 50% and at least twofold higher than the database frequency of the initial state.

Selected amino acid sites not associated with the listed selection forces.

Longitudinal CTL recognition of HIV-1 peptides.

We identified and characterized in detail the epitopic peptides spanning the entire HIV-1 proteome that were recognized by IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells by use of PBMCs cryopreserved from 17 time points. We defined 25 CD8+ T-cell epitopes, including 14 not reported previously (Table 2). Eighteen epitopes were identified using a panel of 769 peptides derived from HIV-1HXB2, HIV-1MN, or consensus sequences covering the whole proteome. Sequences of gp120 and Nef in this subject were largely different from those of the tested peptides. We therefore examined an additional 91 autologous 15-mer peptides derived from the viral sequences found at day 8 across Nef and all five variable regions of Env. The viral population sampled at this time point was virtually homogeneous, with the only genetic diversity corresponding to scattered, clone-specific changes (data not shown). In this process, two additional epitopes (Nef WW9 and Env EY10) were identified.

TABLE 2.

HIV-1-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes recognized by PIC1362

| Protein | Epitope sequencea | Epitope name | HIV-1 protein (epitope position [aa])b | HLA restriction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag | QAISPRTLNAW | Gag QW11 | p24 (13-23) | A*2501 |

| VIPMFSAL | Gag VL8 | p24 (36-43) | Cw*0102 | |

| ETINEEAAEW | Gag EW10 | p24 (71-80) | A*2501 | |

| FRDYVDRFYK | Gag FK10 | p24 (161-170) | B*1801 | |

| Pol | NSPTRREL | Pol NL8 | p6 (35-42) | Cw*0102 |

| EKEGKISKI | Pol EI9 | RT (42-50) | B*5101 | |

| TAFTIPSI | Pol TI8 | RT (128-135) | B*5101 | |

| NNETPGVRY | Pol NY9 | RT (136-144) | B*1801 | |

| ELRQHLLRW | Pol EW9 | RT (204-212) | A*2501 | |

| LPPVVAKEI | Pol LI9 | IN (28-36) | B*5101 | |

| Vpr | EAVRHFPRI | Vpr EI9 | Vpr (29-37) | B*5101 |

| IYETYGDTW | Vpr IW9 | Vpr (46-54) | A*2501 | |

| Vpu | HAPWDVNDL# | Vpu HL9 | Vpu (74-82) | Cw*0102 |

| Tat | PVDPRLEPW | Tat PW9 | Tat (3-11) | A*2501 |

| CCFHCQVC | Tat CC8 | Tat (30-37) | Cw*1203 | |

| Env | AENLWVTVY# | Env AY9 | gp120 (31-39) | B*1801 |

| YETEVHNVW# | Env YW9 | gp120 (61-69) | B*1801 | |

| NVTENFNMW | Env NW9 | gp120 (88-96) | A*2501 | |

| YCAPAGFAIL | Env YL10 | gp120 (217-226) | Cw*0102 | |

| EIIGDIRQAY* | Env EY10 | gp120 (322-330) | A*2501 | |

| TLSQIVTKL# | Env TL9 | gp120 (341-349) | A*0201 | |

| RAIEAQQHLc | Env RL9 | gp41 (46-54) | B*5101 | |

| YSPLSLQTL# | Env YL9 | gp41 (201-209) | Cw*0102 | |

| Nef | WSKSSIIGW* | Nef WW9 | Nef (5-13) | A*2501 |

| YPLTFGWCFc | Nef YF9 | Nef (135-143) | B*1801 |

Amino acid sequences of CD8+ T-cell epitopes identified by IFN-γ ELISPOT assays are shown, with newly defined epitopes highlighted in bold. Epitope sequences are identical to the autologous sequences obtained from the first time point, 8 days after the onset of acute symptoms. Epitopes labeled with an asterisk (*) were identified using a set of 91 autologous peptides from Nef and the variable loops of Env. Epitopes labeled with a number symbol (#) were identified using a set of 78 autologous peptides encompassing selective sites outside of Nef and the variant loops of Env. All other epitopes were identified using peptides based on an HIV-1 clade B lab strain (HXB2 or MN) or consensus sequences. Amino acid sites identified as potentially having experienced positive selection are underlined.

HXB2 amino acid numerations are used.

These two epitopes were identified first using epitope sequence RAIEAQQML derived from the HIV-1MN sequence and epitope sequence YPLTFGWCY derived from the HIV-1HXB2 sequence (the differences are underlined). The IFN-γ SFC frequencies responding to the autologous and the lab strain epitopic peptides were similar.

To identify T-cell determinants within other regions of the day 8 virus would have required synthesis and analysis of 369 additional 15-mer peptides. Instead, we generated and tested 78 autologous 15-mer peptides whose sequences corresponded to the remaining unexamined 29 selected sites across the viral proteome. This yielded identification of five more newly described epitopes: Vpu HL9, Env AY9, Env YW9, Env TL9, and Env YL9. In addition, the two epitopes (Nef WW9 and Env EY10) detected using 15-mer peptides derived from full-length Nef and variable loops of Env would have been identified using 15-mer peptides corresponding to selected sites. Thus, inference of genetic selection was a more productive path to finding epitopes than broad screening of autologous sequences from a single time point.

CD8+ T-cell-mediated responses were restricted by all six of this subject's HLA class I alleles: 9 by HLA-A, 10 by HLA-B, and 6 by HLA-C alleles (Table 2). Notably, Env was the richest region for CTL recognition, with eight reactive epitopes, including five identified only by use of autologous peptides encompassing selected sites.

Relationship between amino acid sites under positive selection and CD8+ T-cell recognition and escape.

For each CTL epitope identified, we also tested T-cell recognition of the mutant forms detected over time. Functional avidity, summarized by EC50 values, was characterized for responses to both the wild-type and mutant forms by use of T cells obtained at the time point at which the epitope elicited peak responses. Mutant forms with EC50 values at least 10-fold higher than those of the corresponding wild-type epitope forms were designated escape mutants. Escape mutations occurred at 25 amino acid sites within 16 epitopes. Of note, 13 sites of mutation were within seven Env epitopes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

HIV-1-specific CTL escape mutants in PIC1362

| Epitope sequencea | HIV-1 protein (epitope position [aa])b | Mutant sequencec | EC50

|

Selection coefficient (s) (95% CI)g | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epitope (nM)d | Mutant (nM)e | Ratiof | ||||

| QAISPRTLNAW | p24 (13-23) | QALSPRTLNAW | 500 | 1,200 | 2.4 | |

| ETINEEAAEW | p24 (71-80) | ETINDEAAEW | 70 | 1,900 | 27 | |

| NSPTRREL | p6Pol (35-42) | NSPTSPTRREL | 20 | NR | F | 0.0220 |

| TSPTRREL | NR | F | ||||

| TAFTIPSI | RT (128-135) | TAFTIPST | 19 | >2,000 | >100 | 0.0372 (0.00597 to 0.0694) |

| TAFTIPSR | >2,000 | >100 | ||||

| TAFTIPSV | >2,000 | >100 | ||||

| NNETPGVRY | RT (136-144) | NNETPGIRY | 20 | 0.3 | 0.015 | 0.1588 (0.1051 to 0.2149) |

| NSETPGVRY | 0.24 | 0.012 | ||||

| NNEIPGVRY | 32 | 1.6 | ||||

| NNEIPGIRY | 45 | 2.25 | ||||

| NNGTPGVRY | 440 | 22 | ||||

| NNEVPGIRY | 0.035 | 0.002 | ||||

| ELRQHLLRW | RT (204-212) | ELRQHLLKW | 116 | NR | F | 0.00242 (0.00113 to 0.00597) |

| EAVRHFPRI | Vpr (29-37) | EAVRHFPRT | 30 | 1,280 | 43 | 0.2432 |

| EAVRHFPRL | 550 | 18 | ||||

| HAPWDVNDL | Vpu (74-82) | HAPWDVNDM | 270 | >1,000 | >3.7 | |

| PVDPRLEPW | Tat (3-11) | PVDPRLDPW | 428 | NR | F | 0.0149 (0.0105 to 0.0194) |

| PVDPSLEPW | NR | F | ||||

| PVDPKLEPW | NR | F | ||||

| CCFHCQVC | Tat (30-37) | CCLHCQVC | 212 | NR | F | 0.414 |

| CCFHCQSC | NR | F | ||||

| AENLWVTVY | gp120 (31-39) | ADNLWVTVY | 37 | 15 | 0.45 | 0.0131 (0.00774 to 0.0185) |

| TDNLWVTVY | 5.9 | 0.159 | ||||

| TEDLWVTVY | NR | F | ||||

| EEDLWVTVY | NR | F | ||||

| AEDSWVTVY | NR | F | ||||

| YETEVHNVW | gp120 (61-69) | YGTEVHNVW | 12 | 267 | 22 | 0.0131 (0.00774 to 0.0185) |

| YDTEVHNVW | 154 | 13 | ||||

| YETEAHNVW | 0.07 | 0.0056 | ||||

| YDTEAHNVW | >1,000 | >83 | ||||

| NVTENFNMW | gp120 (88-96) | NVTEDFDMW | 1,340 | NR | F | 0.0125 (−0.0192 to 0.0452) |

| NVTEEFDMW | NR | F | ||||

| NVTESFDMW | NR | F | ||||

| YCAPAGFAIL | gp120 (217-226) | YCAPAGFAII | 66 | NR | F | 0.0238 (0.0109 to 0.0368) |

| EIIGDIRQAY | gp120 (322-330) | QIIGDIRQAY | 4.6 | >1,000 | >200 | 0.0167 (0.00708 to 0.0265) |

| DIIGDIRQAH | 160 | 34 | ||||

| EIIGNIRQAH | 73 | 15.9 | ||||

| EIIGDIRQAH | NR | F | ||||

| TLSQIVTKL | gp120 (341-349) | TLSKIVTKL | 51 | NR | F | 0.0107 (0.00877 to 0.0127) |

| YSPLSLQTL | gp41 (201-209) | YSPLSLQTR | 82 | NR | F | |

| WSKSSIIGW | Nef (5-13) | WSKTSIIGW | 91 | NR | F | 0.0285 (0.0217 to 0.0354) |

| WSKSSMIGW | 91 | NR | F | |||

Amino acid sequences of identified CTL epitopes are shown, with amino acid sites potentially having experienced positive selection underlined. Epitope sequences are identical to the autologous viral sequences obtained from the first time point, 8 days after the onset of acute symptoms.

HXB2 amino acid numerations are used.

Sequences of mutant forms of identified CTL epitopes are shown, with mutated amino acids underlined.

The EC50 was measured at the time point when the epitope elicited peak CTL responses. The EC50 is defined as the effective concentration giving 50% of signal, based on peptide titration and generation of a dose-response curve.

NR, no response, i.e., CTL recognition of the mutant form was not detected by ELISPOT assays and the EC50 of the mutant form was not measured.

EC50 ratio = EC50 of mutant form/EC50 of epitope. F, full escape, i.e., CTL recognition of the mutant form was not detected. Other mutant forms are partial (EC50 ratio ≥ 10) or not (EC50 ratio < 10) escape mutants. Full and partial escapes are shown in bold.

For some epitopes, there was a lack of data between time points where the mutants were first detected and where the mutant reached 100%. Therefore, in these cases no 95% CIs were calculated.

As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1C, of the 73 selected sites, 22 (30%) were located within 16 CTL epitopes identified in our longitudinal analysis. Fourteen of these 16 epitopes developed escape mutations, accounting for 20 of the selected sites. Approximately one-third (7 of 22) of the epitope-associated selected sites were identified only by the method for detection of directional selection (21% of the sites experiencing directional selection), with the remaining two-thirds identified through detection of diversifying selection (38% of this category of selected sites).

Selected sites flanking CTL epitopes.

CTL escape can be mediated both by mutations within an epitope that result in poor binding to the presenting HLA class I molecules and/or the T-cell receptor and by amino acid changes flanking an epitope, with escape resulting from impaired processing and presentation (4, 13, 60). Of the 51 selected sites not in CTL epitopes, 12 were located in the flanking regions within 10 amino acids of the epitopes (Fig. 1C), of which 7 were located within 5 amino acids of the epitopes.

Apparent selective advantage of escape mutants.

CTL responses to two epitopes, CCFHCQVC (Tat CC8, amino acids [aa] 30 to 37) and EAVRHFPRI (Vpr EI9, aa 29 to 37), were detected as early as day 8, and escape mutants were observed as early as day 50 after onset of acute symptoms (11). The Vpr EI9 escape variant completely replaced the epitope within 54 days (0/15 at day 22 versus 10/10 at day 76), corresponding to approximately 27 generations (assuming a 2.0-day replication cycle [38]). For Tat CC8, escape mutants increased from 0/17 to 9/9 within 29 days. Selection coefficients of the mutants were thus calculated to be 0.24 for Vpr EI9 and 0.41 for Tat CC8 (see Materials and Methods), indicating that in the presence of CTL responses, the mutants had a 24% or 41% increased likelihood for survival and replication over the wild type. The selective coefficients of other CTL escape mutants ranged from 0.0024 to 0.15, with an average of 0.03. Thus, it appeared that the escape mutants from the earliest CTL recognition conferred a higher survival advantage than the later-appearing mutants.

Association of amino acid sites under positive selection with other adaptive immune responses.

To estimate the possible effects of other immune responses, namely, helper T-lymphocyte (HTL) and humoral immune responses, on the selection of HIV-1 variants, we compared the observed viral sequences to epitopes of CD4+ HTL and neutralizing antibodies reported in the HIV-1 immunology database (29). We found that eight of the selected amino acid sites were located in known HTL epitopes (Fig. 1C). However, four of these, p24-15I, RT-135I, RT-211R, and gp120-226L, were also within confirmed CD8+ T-cell epitopes. No selected site in Env was located within a known neutralizing antibody binding site, and only one change, I399S in gp120, resulted in the acquisition of an N-linked glycosylation site (Fig. 1C).

Association of amino acid mutations mediating CTL escape with viral database frequency.

Amino acids associated with high viral replicative fitness are likely to be carried with high frequency in HIV infection. Indeed, infection of a new host results in the reacquisition of mutations that are more ancestral or consensus-like (23). Therefore, viruses with amino acids found at higher frequencies in the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) HIV sequence database (32) might reasonably be hypothesized to be associated with better replicative capacity or to be more stable in the absence of host immune pressure (3). Exceptions may include those within peptides that have been adapted extensively to a human population with shared HLA alleles (33, 40). We compared the frequencies of amino acids at each escape position in their original and escape mutant forms in the subtype B database (32). In our study, the database frequencies of the amino acids responsible for CTL escape were significantly lower than those of the corresponding amino acids found in the recognized epitope (P = 0.0021, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

Amino acid changes associated with transmission and outgrowth early in infection.

To identify sites associated with viral outgrowth in the newly infected host, we sequenced 10 full-length viral genomes from plasma of the subject's sexual partner (PIC1365) obtained 1 month after onset of acute symptoms in subject PIC1362. Phylogenetic analysis of random sequences of C2-V5 of Env (and other regions) from the LANL sequence database and those from PIC1362 and PIC1365 showed monophyletic clustering between sequences from PIC1362 and PIC1365 (data not shown). This is consistent with historical documentation that PIC1365 was the transmitting source partner. Comparing sequences from PIC1362, PIC1365, and known HIV-1 CTL epitopes specific only to PIC1365's class I HLA alleles (A*0101, B*0801, B*5001/5004, Cw*0602, and Cw*0701) in the LANL HIV immunology database (29), we identified two selected sites in the recipient (PIC1362) within p17 (aa 31) and Nef (aa 94). Of interest, these amino acid changes resided at putative anchor residues (underlined) within two HLA-B8-restricted epitopes, GGKKKYKL, Gag GL8, of p17 (aa 24 to 31) and FLKEKGGL, Nef FL8, of Nef (aa 90 to 97), and were transmitted from an HLA-B8-positive donor (PIC1365) to the HLA-B8-negative recipient (PIC1362) in the form of p17-31F and Nef-94E (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Longitudinal viral sequence analysis of and CTL responses to Gag GL8 and NEF FL8

| Epitope (location [aa]) | Subject | Sampling time(s) (day[s])a | Sequence | Clonal frequency (%) | CTL response (SFC)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag GL8 (p17 24-31) | GGKKKYKLb | ||||

| PIC1365 | 23 | -------F | 6/10 (60) | <50 | |

| -------Lc | 4/10 (40) | <50 | |||

| 1501 | -------Lc | 10/10 (100) | 185 | ||

| PIC1362 | 8, 50, 190 | -------F | 39/39 (100) | ||

| 344, 491 | -------F | 13/29 (45) | |||

| -------Ld | 16/29 (55) | ||||

| 667 | -------F | 2/15 (13) | |||

| -------Ld | 13/15 (87) | ||||

| 826 | -------F | 1/10 (10) | |||

| -------Ld | 9/10 (90) | ||||

| 1035 | -------F | 3/16 (19) | |||

| -------Ld | 13/16 (81) | ||||

| FL8 (Nef 90-97) | FLKEKGGLb | ||||

| PIC1365 | 23 | ----E--- | 8/10 (80) | <50 | |

| ---VE--- | 2/10 (20) | ||||

| ----K--- | 0/10 (0) | <50 | |||

| 1501 | ----K--- | <50 | |||

| PIC1362 | 8, 22, 50 | ----E--- | 37/39 (95) | ||

| ----E---P | 1/39 (2.5) | ||||

| ---GE--- | 1/39 (2.5) | ||||

| 76, 113 | ----E--- | 22/26 (84) | |||

| ----G--- | 2/26 (7) | ||||

| ----K--- | 2/26 (7) | ||||

| 155 | ----E--- | 7/10 (70) | |||

| ----K--- | 3/10 (30) | ||||

| 190 | ----E--- | 4/15 (27) | |||

| ----K--- | 11/15 (73) | ||||

| 344, 580, 769, 826, | ----K--- | 65/68 (95.5) | |||

| 1035 | ---EK--- | 1/68 (1.5) | |||

| C---K--- | 1/68 (1.5) | ||||

| S---K--- | 1/68 (1.5) |

Sampling times are indicated by days after onset of acute symptoms in the recipient, subject PIC1362.

Sequence of the HLA-B8 epitope form.

The 31L is encoded by CTA.

The 31L is encoded by CTC, CTT, or TTA.

Shown are CTL responses (SFC/106 cells) to the peptides in the Sequence column, measured by ELISPOT assay. The response was considered ELISPOT positive when the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells was over 50 SFC/106 PBMC and greater than twice the background level.

Several studies demonstrated that the Nef sequence FLKEEGGL may be highly unfavorable for HLA-B8 binding and CTL recognition (21, 46). The Nef sequence transmitted to PIC1362 thus may correspond to an escape form of the epitope in donor PIC1365. No CTL recognition of any autologous 15-mer encompassing Gag p17-31 and Nef-94 was detected in the HLA-B8-negative recipient throughout the course of the study. Nonetheless, viruses in the form of p17-31L and Nef-94K later came to be predominant in the recipient. The selection coefficient calculated for p17-31L was 0.00600 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.00285 to 0.00916), and that for Nef-94K was 0.0332 (0.0181 to 0.0485). Furthermore, it should be noted that 40% of the sequences found in the donor shortly after transmission to PIC1362 were in the form of p17-31L, with 31L encoded by CTA. At later times in the recipient, however, p17-31L was encoded by CTC, CTT, or TTA, indicating that outgrowth of p17-31L in the recipient was most likely due to selection following de novo mutation from phenylalanine (F) to leucine (L) and not outgrowth of p17-31L viruses transmitted from the donor.

The database frequency is 100% for p17-31L and 91% for Nef-94K for subtype B. Therefore, the selection for p17-31L and Nef-94K in the recipient suggests that viruses evolved toward the higher-database-frequency form, likely the more replication-fit form, in the absence of corresponding CTL responses. We detected no CTL responses to either p17-31 or Nef-94 peptides in the donor at the time point just following transmission (Table 4). However, 4 years later, all of the sampled viruses from the donor were in the form p17-31L and a low-level ELISPOT assay response (185 spot-forming cells [SFC]/106 PBMCs) was detected. This is consistent with the idea that the viruses with p17-31F were escape mutants in PIC1365 and that this escape might be associated with fitness cost. Loss of the epitope form, leading to a decay of CTL pressure in PIC1365, may have accounted for the late development of the epitope form of p17-31L, which was then followed by reemergence of a CTL response.

Of the 73 selected sites (Fig. 1C), 21 (29%), including p17-31 and Nef-94, were found with sequence changes evolved from those at a lower subtype B database frequency (<50% at early infection) to those at a database frequency at least twofold higher and with over 50% database frequency. Moreover, 86% (18/21) of these sites evolving to amino acids of higher database frequency were not within CTL epitopes recognized in PIC1362. Of the 18 sites, 15 were identified only by the method for detection of directional selection. Therefore, evolution to enhance replicative fitness, including reversion of CTL escapes with fitness costs in the donor, is very likely to be another significant positive-selection force in HIV-1 infection.

We were not able to implicate known selective forces for the remaining 20 selected amino acid sites not accounted for as discussed above (Fig. 1C). However, 15 of these sites were in Env, the principal target of the humoral immune response. It is therefore possible that some of these sites in Env were selected as a result of conferring escape from presently undefined humoral immune responses.

DISCUSSION

Our study reveals that among the large amount of viral genomic variation that occurs within an HIV-1-infected host, those relatively few amino acid sites that undergo positive selection by predefined criteria exert a critical role in adapting to the host immune response. In our intensive longitudinal data set of 15 time points over the first 3 years following acute infection in PIC1362, we demonstrate that only 73 of the 1,063 (6.9%) polymorphic amino acid sites underwent what we could define as directional or diversifying selection. Notably, this selection occurred throughout the HIV-1 proteome, involving eight of the nine viral proteins. Moreover, T-cell responses, particularly those of CD8+ CTL, exhibited the single greatest immune response that can account for these changes.

We found CTL epitopic responses, as well as escape mutations, within seven of the HIV-1 proteins, which together were restricted by all six of the subject's HLA alleles. Sixteen of the 25 epitopes detected (64%) developed escape mutations over the course of the first 3 years of infection. Four of the epitopes that developed escape mutations were identified only by using peptides encompassing selective sites. Thus, we may have overestimated the percentage of epitopes with escape mutations. However, excluding these four epitopes, we still found that 12 of 21 (57%) epitopes developed escape mutations. A total of 22 of the 73 selected sites identified (30%) were in 16 confirmed CTL epitopes, and 20 of these sites were located in 14 CTL epitopes in which escape mutations occurred. An additional 12 selected sites were located within 10 amino acids flanking an epitope, where mutations might impair epitope processing and presentation (4, 13, 60). Fewer responses could be readily attributed to HTL (≤8 sites) or neutralizing antibodies (1 site). In addition, 21 selected sites (29%), including 18 not located in CTL epitopes recognized in this subject, were found to mutate from a form of low database representation to a form of high database representation. Mutations at two of these sites appeared to revert two donor-specific epitopes from CTL escape mutant forms in the donor to their epitopic forms in the recipient. Thus, in the absence of the selective pressure of a targeted immune response, these amino acids may have reverted to the more common, epitopic forms.

In a recent study (3), Allen et al. monitored four HIV-1-infected subjects for viral sequence changes in the 4 to 5 years following acute infection. Consensus whole-genome sequences, excluding Env, were determined over time. Fifty-three percent of the accumulating mutations (equivalent to the selected sites described here) they reported were associated with CTL responses. This compares with 30% of the mutations we studied over the whole proteome in recognized epitopes, or 43% if we exclude Env. In addition, 18% of the mutations they detected were associated with mutations towards more common HIV-1 subtype B consensus sequences, and these sites were inferred to be reversions of transmitted CTL escape mutants. This compares to 25% of the mutations we found, or 30% if we exclude Env. Last, 29% of the mutations detected by Allen et al. were not linked to cellular immune responses or reversion, compared to 45% overall in our study, or 38% outside Env. Our results are therefore in substantial agreement with this and other previous studies (3, 24) and confirm that in the first few years of infection, escape from CTL responses and improvements in replication fitness are two major positive-selection forces shaping the natural course of HIV-1 evolution across the viral proteome.

Amino acid sites under positive selection were typically inferred when the codon exhibited an excessive nonsynonymous-substitution distance compared to the synonymous-substitution distance. This method is sensitive for identifying amino acid sites under diversifying selection, in which mutations to multiple other amino acids are advantageous, or parallel evolution, in which the same mutation recurs in separate lineages. However, this method largely fails to identify amino acid sites under directional selection, in which mutation to one particular advantageous amino acid occurs once. Hence, to identify amino acid sites under directional selection, we developed a method to screen sequences for sites showing a mutant frequency that increased faster than one would expect under random genetic drift. Thirty-four of the 73 selected sites were identified by this method but were missed by nonsynonymous/synonymous-distance analysis. Of the directionally selected amino acid sites, 7 were associated with CTL responses and 15 were correlated with fitness improvement. Therefore, our method for identification of sites under directional selection should be very useful for epitope identification as well as studies of viral evolution and host-virus interactions.

CTL responses against HIV-1 infection are commonly assessed using peptides derived from lab strains. The use of peptides derived from consensus sequences has improved the detection rate of CTL responses, with further increases noted by use of peptides based on autologous viral sequences (6, 15). However, due to the high degree of genetic variation between HIV-1 strains both among and within infected individuals, it is impractical to estimate CTL responses by using all autologous peptides, and such an approach is likely to have a low yield of immune-targeted sites. Indeed, when we synthesized 91 autologous 15-mer peptides derived from the viral sequences dominating initial infection, and covering full-length Nef and the variable loops of Env, we identified only two new epitopes. In a more targeted approach, we used positively selected sites detected by computational analyses to guide identification of autologous epitopes. In this way, we identified these two plus five new epitopes by using 78 autologous 15-mers covering selected sites, a threefold- to fourfold-better rate of detection of epitopes. Thus, designing and testing autologous peptides based on amino acid sites under positive selection is a powerful and cost-saving method to identify CTL epitopes missed by conventional methods that employ only peptides derived from reference strains or consensus sequences. It also needs to be noted that selection-based methods are biased to identify CTL epitopes that escaped recognition, whereas epitopes with minimum evolution are missed by these methods.

Prior studies have omitted Env from study (3) or generally failed to show that Env is as important a CTL target as Nef, Gag, and Pol (2, 7, 45). The use of autologous peptides targeted by inclusion of selected sites, however, showed that Env was the gene product most frequently targeted by CTL in this subject, with eight reactive epitopes, of which seven developed escape mutations. Indeed, five of the eight Env epitopes identified were detected only by using autologous peptides covering selected sites. Thus, as a result of the exceptionally high variability in Env, CTL responses to Env will remain underappreciated if only peptides derived from consensus or lab strains are examined.

Although CTL escape mutants are advantageous in terms of escaping immunity, they may have replication fitness costs (4, 16, 19, 24, 34). Our study showed that compared to the epitopic forms, mutants mediating CTL escapes were associated with low database frequency, implying fitness costs of these mutations. In addition, 18/51 (35%) of the selected amino acid sites not in recognized CTL epitopes were found to have mutated from lower-database-frequency forms to higher-database-frequency forms, including two sites at which mutations appeared to result in reversion of CTL escape mutants present in the donor. This suggests the existence of selective pressure in the new host to improve replication fitness when the site is no longer targeted by an active immune response.

Given the extensive CTL escape mutants observed with PIC1362 and by other studies (4, 5, 9, 11, 17, 20, 24, 46, 55), it is surprising to note that only two amino acid sites at which mutations appeared to result in reversion of potential CTL escape mutants were identified in the infecting partner, PIC1365. It may be that many of the escapes that occur within a host have little fitness impact on the virus and thus revert slowly or not at all. Alternatively, compensatory mutations outside the epitopes that affect presentation and restore fitness may obviate the requirement for reversion. In addition, these two sites were identified by comparing sequences from PIC1362, PIC1365, and known HIV-1 CTL epitopes specific to PIC1365's class I HLA alleles in the LANL HIV immunology database (29). It should be noted that this database is substantially incomplete. For example, in the case of PIC1362, 14 of the 25 recognized epitopes were not reported previously. In any case, we did not have specimens available to follow the infecting partner over time and thus are unable to document most of his cellular responses or escape mutations.

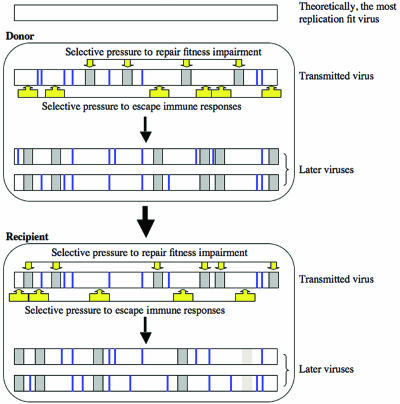

Figure 2 illustrates the balancing selective pressures we hypothesize to play critical roles in shaping the viral proteome. Escape mutants are selected in an HIV-1-infected donor due in large measure to CTL responses. However, many of these escape mutations have a replication fitness cost. Therefore, viruses with these escape mutations are less fit when transmitted to a new host. Viruses in a recipient with different HLA alleles target different stretches of the viral proteome. Thus, a new set of escape mutants, many of which have reduced replicative fitness, is selected. Balancing this effect, escape mutations which occurred in the donor but are no longer under immune pressure in the recipient and which result in impaired fitness come under selective pressure to revert to a state with an amino acid that confers greater fitness. Therefore, pressures to repair impaired replicative fitness of the transmitted viruses and to escape immune responses, especially CTL, are two major positive-selection forces shaping the natural course of HIV-1 evolution.

FIG. 2.

Two major positive-selection forces hypothesized to act on HIV-1 during the natural course of infection: escape from CTL responses and increasing replication fitness. Dark-gray bars indicate immune escape mutations that are balanced by a partial loss in replication fitness. Light-gray bars indicate immune escape mutations that have little or no replication fitness cost. Thick vertical lines indicate sequence differences from the theoretically most replication-fit virus that have no or little effect on viral fitness.

In support of this hypothesis, we have shown recently that the HIV-1 genome is partially “reset” during the early years of HIV-1 infection by developing mutations associated with evolution toward a phylogenetically ancestral state (23). As noted above, epitopic forms of peptides are composed of high-database-frequency amino acid variants, whereas escape forms are typically found at lower database frequencies. Furthermore, we have shown that phylogenetically ancestral states are composed largely of the most common amino acids at each site within the HIV-1 proteome, due in part to convergent evolution in multiple hosts (12, 23). Hence, the resetting of the viral genome we previously observed is hypothesized to be due in part to reversion at amino acid sites to epitopic forms no longer being targeted by CTL responses in the newly infected hosts.

Our findings also have important implications for HIV-1 vaccine designs that seek to reduce disease progression and transmission rates if the goal of sterilizing immunity cannot be attained (41). Immunization against viruses of more-fit form should force replicating viruses that break through this immunity to escape into forms of increasingly lower fitness. Thus, the challenge suggested by our and other recent findings is to develop vaccines that target amino acid variants mediating high fitness and provide wide coverage of different variants (43). Given the frequent CTL targeting at Env observed in this subject by use of autologous peptides, it is also important to include Env as an immunogen in order to elicit maximum cellular as well as humoral responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenjie Deng and Brian Birditt for assistance in sequence submission.

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Services, including support for the Seattle Primary Infection Program (AI57005) and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (AI27757), and by grant M01-RR-00037 for leukapheresis.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achaz, G., S. Palmer, M. Kearney, F. Maldarelli, J. W. Mellors, J. M. Coffin, and J. Wakeley. 2004. A robust measure of HIV-1 population turnover within chronically infected individuals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21:1902-1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addo, M. M., X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, D. Cohen, R. L. Eldridge, D. Strick, M. N. Johnston, C. Corcoran, A. G. Wurcel, C. A. Fitzpatrick, M. E. Feeney, W. R. Rodriguez, N. Basgoz, R. Draenert, D. R. Stone, C. Brander, P. J. Goulder, E. S. Rosenberg, M. Altfeld, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Comprehensive epitope analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T-cell responses directed against the entire expressed HIV-1 genome demonstrate broadly directed responses, but no correlation to viral load. J. Virol. 77:2081-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, S. C. Geer, E. T. Kalife, C. Moore, K. M. O'Sullivan, I. DeSouza, M. E. Feeney, R. L. Eldridge, E. L. Maier, D. E. Kaufmann, M. P. Lahaie, L. Reyor, G. Tanzi, M. N. Johnston, C. Brander, R. Draenert, J. K. Rockstroh, H. Jessen, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Selective escape from CD8+ T-cell responses represents a major driving force of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) sequence diversity and reveals constraints on HIV-1 evolution. J. Virol. 79:13239-13249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen, T. M., M. Altfeld, X. G. Yu, K. M. O'Sullivan, M. Lichterfeld, S. Le Gall, M. John, B. R. Mothe, P. K. Lee, E. T. Kalife, D. E. Cohen, K. A. Freedberg, D. A. Strick, M. N. Johnston, A. Sette, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, P. J. Goulder, C. Brander, and B. D. Walker. 2004. Selection, transmission, and reversion of an antigen-processing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape mutation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 78:7069-7078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen, T. M., X. G. Yu, E. T. Kalife, L. L. Reyor, M. Lichterfeld, M. John, M. Cheng, R. L. Allgaier, S. Mui, N. Frahm, G. Alter, N. V. Brown, M. N. Johnston, E. S. Rosenberg, S. A. Mallal, C. Brander, B. D. Walker, and M. Altfeld. 2005. De novo generation of escape variant-specific CD8+ T-cell responses following cytotoxic T-lymphocyte escape in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 79:12952-12960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altfeld, M., M. M. Addo, R. Shankarappa, P. K. Lee, T. M. Allen, X. G. Yu, A. Rathod, J. Harlow, K. O'Sullivan, M. N. Johnston, P. J. R. Goulder, J. I. Mullins, E. S. Rosenberg, C. Brander, B. Korber, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Enhanced detection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific T-cell responses to highly variable regions by using peptides based on autologous virus sequences. J. Virol. 77:7330-7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betts, M. R., D. R. Ambrozak, D. C. Douek, S. Bonhoeffer, J. M. Brenchley, J. P. Casazza, R. A. Koup, and L. J. Picker. 2001. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J. Virol. 75:11983-11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrow, P., H. Lewick, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1994. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 68:6103-6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borrow, P., H. Lewicki, X. Wei, M. S. Horwitz, N. Peffer, H. Meyers, J. A. Nelson, J. E. Gairin, B. H. Hahn, M. B. Oldstone, and G. M. Shaw. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat. Med. 3:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao, J., J. McNevin, S. Holte, L. Fink, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Comprehensive analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific gamma interferon-secreting CD8+ T cells in primary HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 77:6867-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao, J., J. McNevin, U. Malhotra, and M. J. McElrath. 2003. Evolution of CD8+ T cell immunity and viral escape following acute HIV-1 infection. J. Immunol. 171:3837-3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doria-Rose, N., G. H. Learn, A. G. Rodrigo, D. C. Nickle, F. Li, M. Malahanabis, M. T. Hensel, S. McLaughlin, P. F. Edmonson, D. Montefiori, S. W. Barnett, N. L. Haigwood, and J. I. Mullins. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype B ancestral envelope protein is functional and elicits neutralizing antibodies in rabbits similar to those elicited by a circulating subtype B envelope. J. Virol. 79:11214-11224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draenert, R., S. Le Gall, K. J. Pfafferott, A. J. Leslie, P. Chetty, C. Brander, E. C. Holmes, S. C. Chang, M. E. Feeney, M. M. Addo, L. Ruiz, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, M. Altfeld, S. Thomas, Y. Tang, C. L. Verrill, C. Dixon, J. G. Prado, P. Kiepiela, J. Martinez-Picado, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. Immune selection for altered antigen processing leads to cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape in chronic HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 199:905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draenert, R., C. L. Verrill, Y. Tang, T. M. Allen, A. G. Wurcel, M. Boczanowski, A. Lechner, A. Y. Kim, T. Suscovich, N. V. Brown, M. M. Addo, and B. D. Walker. 2004. Persistent recognition of autologous virus by high-avidity CD8 T cells in chronic, progressive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 78:630-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frahm, N., B. T. Korber, C. M. Adams, J. J. Szinger, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. E. Feeney, K. Yusim, K. Sango, N. V. Brown, D. SenGupta, A. Piechocka-Trocha, T. Simonis, F. M. Marincola, A. G. Wurcel, D. R. Stone, C. J. Russell, P. Adolf, D. Cohen, T. Roach, A. StJohn, A. Khatri, K. Davis, J. Mullins, P. J. R. Goulder, B. D. Walker, and C. Brander. 2004. Consistent cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte targeting of immunodominant regions in human immunodeficiency virus across multiple ethnicities. J. Virol. 78:2187-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedrich, T. C., E. J. Dodds, L. J. Yant, L. Vojnov, R. Rudersdorf, C. Cullen, D. T. Evans, R. C. Desrosiers, B. R. Mothe, J. Sidney, A. Sette, K. Kunstman, S. Wolinsky, M. Piatak, J. Lifson, A. L. Hughes, N. Wilson, D. H. O'Connor, and D. I. Watkins. 2004. Reversion of CTL escape-variant immunodeficiency viruses in vivo. Nat. Med. 10:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geels, M. J., M. Cornelissen, H. Schuitemaker, K. Anderson, D. Kwa, J. Maas, J. T. Dekker, E. Baan, F. Zorgdrager, R. van den Burg, M. van Beelen, V. V. Lukashov, T. M. Fu, W. A. Paxton, L. van der Hoek, S. A. Dubey, J. W. Shiver, and J. Goudsmit. 2003. Identification of sequential viral escape mutants associated with altered T-cell responses in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individual. J. Virol. 77:12430-12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gojobori, T., Y. Yamaguchi, K. Ikeo, and M. Mizokami. 1994. Evolution of pathogenic viruses with special reference to the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitutions. Jpn. J. Genet. 69:481-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goulder, P. J., C. Brander, Y. Tang, C. Tremblay, R. A. Colbert, M. M. Addo, E. S. Rosenberg, T. Nguyen, R. Allen, A. Trocha, M. Altfeld, S. He, M. Bunce, R. Funkhouser, S. I. Pelton, S. K. Burchett, K. McIntosh, B. T. Korber, and B. D. Walker. 2001. Evolution and transmission of stable CTL escape mutations in HIV infection. Nature 412:334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goulder, P. J., R. E. Phillips, R. A. Colbert, S. McAdam, G. Ogg, M. A. Nowak, P. Giangrande, G. Luzzi, B. Morgan, A. Edwards, A. J. McMichael, and S. Rowland-Jones. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3:212-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulder, P. J., S. W. Reid, D. A. Price, C. A. O'Callaghan, A. J. McMichael, R. E. Phillips, and E. Y. Jones. 1997. Combined structural and immunological refinement of HIV-1 HLA-B8-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:1515-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartl, D. L., and A. G. Clark. 1997. Principles of population genetics, 3rd ed., p. 211-266. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 23.Herbeck, J. T., D. C. Nickle, G. H. Learn, G. S. Gottlieb, M. E. Curlin, L. Heath, and J. I. Mullins. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env evolves toward ancestral states upon transmission to a new host. J. Virol. 80:1637-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, N. A., X. Wei, D. R. Flower, M. Wong, F. Michor, M. S. Saag, B. H. Hahn, M. A. Nowak, G. M. Shaw, and P. Borrow. 2004. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 escape from the primary CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. J. Exp. Med. 200:1243-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiepiela, P., A. J. Leslie, I. Honeyborne, D. Ramduth, C. Thobakgale, S. Chetty, P. Rathnavalu, C. Moore, K. J. Pfafferott, L. Hilton, P. Zimbwa, S. Moore, T. Allen, C. Brander, M. M. Addo, M. Altfeld, I. James, S. Mallal, M. Bunce, L. D. Barber, J. Szinger, C. Day, P. Klenerman, J. Mullins, B. Korber, H. M. Coovadia, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432:769-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura, M. 1983. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 27.Koibuchi, T., T. M. Allen, M. Lichterfeld, S. K. Mui, K. M. O'Sullivan, A. Trocha, S. A. Kalams, R. P. Johnson, and B. D. Walker. 2005. Limited sequence evolution within persistently targeted CD8 epitopes in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 79:8171-8181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korber, B. T., K. MacInnes, R. F. Smith, and G. Myers. 1994. Mutational trends in V3 loop protein sequences observed in different genetic lineages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:6730-6744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korber, B. T. M., C. Brander, B. F. Haynes, R. Koup, J. P. Moore, B. D. Walker, and D. I. Watkins (ed). 2005. HIV molecular immunology 2005. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos, N.Mex. LA-UR 06-0036.

- 30.Koup, R. A., J. T. Safrit, Y. Cao, C. A. Andrews, G. McLeod, W. Borkowsky, C. Farthing, and D. D. Ho. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650-4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leigh-Brown, A. J. 1997. Analysis of HIV-1 env gene sequences reveals evidence for a low effective number in the viral population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1862-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leitner, T., B. Foley, B. Hahn, P. Marx, F. McCutchan, J. Mellors, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber (ed.). 2003. HIV sequence compendium 2003. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos, N.Mex. LA-UR 04-7420.

- 33.Leslie, A., D. Kavanagh, I. Honeyborne, K. Pfafferott, C. Edwards, T. Pillay, L. Hilton, C. Thobakgale, D. Ramduth, R. Draenert, S. Le Gall, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, C. Brander, A. K. Sewell, S. Moore, J. Mullins, C. Moore, S. Mallal, N. Bhardwaj, K. Yusim, R. Phillips, P. Klenerman, B. Korber, P. Kiepiela, B. Walker, and P. Goulder. 2005. Transmission and accumulation of CTL escape variants drive negative associations between HIV polymorphisms and HLA. J. Exp. Med. 201:891-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leslie, A. J., K. J. Pfafferott, P. Chetty, R. Draenert, M. M. Addo, M. Feeney, Y. Tang, E. C. Holmes, T. Allen, J. G. Prado, M. Altfeld, C. Brander, C. Dixon, D. Ramduth, P. Jeena, S. A. Thomas, A. StJohn, T. A. Roach, B. Kupfer, G. Luzzi, A. Edwards, G. Taylor, H. Lyall, G. Tudor-Williams, V. Novelli, J. Martinez-Picado, P. Kiepiela, B. D. Walker, and P. J. Goulder. 2004. HIV evolution: CTL escape mutation and reversion after transmission. Nat. Med. 10:282-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, S.-L., A. G. Rodrigo, R. Shankarappa, G. H. Learn, L. Hsu, O. Davidov, L. P. Zhao, and J. I. Mullins. 1996. HIV quasispecies and resampling. Science 273:415-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, S.-L., T. Schacker, L. Musey, D. Shriner, M. J. McElrath, L. Corey, and J. I. Mullins. 1997. Divergent patterns of progression to AIDS after infection from the same source: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution and antiviral responses. J. Virol. 71:4284-4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malhotra, U., S. Holte, S. Dutta, M. M. Berrey, E. Delpit, D. M. Koelle, A. Sette, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 2001. Role for HLA class II molecules in HIV-1 suppression and cellular immunity following antiretroviral treatment. J. Clin. Investig. 107:505-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markowitz, M., M. Louie, A. Hurley, E. Sun, M. Di Mascio, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 2003. A novel antiviral intervention results in more accurate assessment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication dynamics and T-cell decay in vivo. J. Virol. 77:5037-5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mascola, J. R. 2003. Defining the protective antibody response for HIV-1. Curr. Mol. Med. 3:209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore, C. B., M. John, I. R. James, F. T. Christiansen, C. S. Witt, and S. A. Mallal. 2002. Evidence of HIV-1 adaptation to HLA-restricted immune responses at a population level. Science 296:1439-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mullins, J. I. 1997. Curtailing the AIDS pandemic. Science 276:1955-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musey, L., J. Hughes, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nickle, D. C., M. Rolland, S. L. Kosakovsky Pond, W. Deng, M. Seligman, M. A. Jensen, V. Jojic, C. Kadie, D. Heckerman, J. I. Mullins, and N. Jojic. Submitted for publication.

- 44.Norris, P. J., and E. S. Rosenberg. 2002. CD4+ T helper cells and the role they play in viral control. J. Mol. Med. 80:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novitsky, V., H. Cao, N. Rybak, P. Gilbert, M. F. McLane, S. Gaolekwe, T. Peter, I. Thior, T. Ndung'u, R. Marlink, T. H. Lee, and M. Essex. 2002. Magnitude and frequency of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses: identification of immunodominant regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C. J. Virol. 76:10155-10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Price, D. A., P. J. Goulder, P. Klenerman, A. K. Sewell, P. J. Easterbrook, M. Troop, C. R. Bangham, and R. E. Phillips. 1997. Positive selection of HIV-1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape variants during primary infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1890-1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramratnam, B., S. Bonhoeffer, J. Binley, A. Hurley, L. Zhang, J. E. Mittler, M. Markowitz, J. P. Moore, A. S. Perelson, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Rapid production and clearance of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus assessed by large volume plasma apheresis. Lancet 354:1782-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodrigo, A. G., and J. I. Mullins. 1996. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular evolution and the measure of selection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:1681-1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmitz, J. E., M. J. Kuroda, S. Santra, V. G. Sasseville, M. A. Simon, M. A. Lifton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. Dalesandro, B. J. Scallon, J. Ghrayeb, M. A. Forman, D. C. Montefiori, E. P. Rieber, N. L. Letvin, and K. A. Reimann. 1999. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seo, T.-K., J. L. Thorne, M. Hasegawa, and H. Kishino. 2002. Estimation of effective population size of HIV-1 within a host: a pseudomaximum-likelihood approach. Genetics 160:1283-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shankarappa, R., J. B. Margolick, S. J. Gange, A. G. Rodrigo, D. Upchurch, H. Farzadegan, P. Gupta, C. R. Rinaldo, G. H. Learn, X. He, X. L. Huang, and J. I. Mullins. 1999. Consistent viral evolutionary changes associated with the progression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 73:10489-10502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shriner, D., D. C. Nickle, M. A. Jensen, and J. I. Mullins. 2003. Potential impact of recombination on sitewise approaches for detecting positive natural selection. Genet. Res. 81:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swofford, D. L. 1999. PAUP* 4.0: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), 4.0b2a ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Mass.

- 55.Wolinsky, S. M., B. T. Korber, A. U. Neumann, M. Daniels, K. J. Kunstman, A. J. Whetsell, M. R. Furtado, Y. Cao, D. D. Ho, and J. T. Safrit. 1996. Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science 272:537-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang, O. O., P. T. Sarkis, A. Ali, J. D. Harlow, C. Brander, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 2003. Determinant of HIV-1 mutational escape from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 197:1365-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang, O. O., and B. D. Walker. 1997. CD8+ cells in human immunodeficiency virus type I pathogenesis: cytolytic and noncytolytic inhibition of viral replication. Adv. Immunol. 66:273-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang, Z. 1997. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 13:555-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang, Z., R. Nielsen, N. Goldman, and A. M. Pedersen. 2000. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics 155:431-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yokomaku, Y., H. Miura, H. Tomiyama, A. Kawana-Tachikawa, M. Takiguchi, A. Kojima, Y. Nagai, A. Iwamoto, Z. Matsuda, and K. Ariyoshi. 2004. Impaired processing and presentation of cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes are major escape mechanisms from CTL immune pressure in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 78:1324-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yusim, K., C. Kesmir, B. Gaschen, M. M. Addo, M. Altfeld, S. Brunak, A. Chigaev, V. Detours, and B. T. Korber. 2002. Clustering patterns of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) proteins reveal imprints of immune evasion on HIV-1 global variation. J. Virol. 76:8757-8768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.