Abstract

The lytic origins of DNA replication for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), oriLyt-L and oriLyt-R, are located between open reading frames K4.2 and K5 and ORF69 and vFLIP, respectively. These lytic origins were elucidated using a transient replication assay. Although this assay is a powerful tool for identifying many herpesvirus lytic origins, it is limited in its ability to evaluate the activity of replication origins in the context of the viral genome. To this end, we investigated the ability of a recombinant HHV8 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) to replicate in the absence of oriLyt-R, oriLyt-L, or both oriLyt regions. We generated the HHV8 BAC recombinants (BAC36-ΔOri-R, BAC36-ΔOri-L, and BAC36-ΔOri-RL), which removed one or all of the identified lytic origins. An evaluation of these recombinant BACs revealed that oriLyt-L was sufficient to propagate the viral genome, whereas oriLyt-R alone failed to direct the amplification of viral DNA.

Transient transfection experiments suggest that lytic replication of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) is directed by two origins of DNA replication, oriLyt-L and oriLyt-R (2, 10). Fine mapping studies indicated that several DNA elements contained within these lytic origins play essential or ancillary roles in the efficient amplification of cloned oriLyt (1, 17). The HHV8 oriLyt regions contain two A+T-rich regions that flank the DNA sequence that contains several consensus CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha sites, along with a promoter region that is composed of an ORF50 response element (1, 13, 17). This promoter sequence apparently drives the expression of a small transcript downstream of the ORF50 response element (1, 17). In addition, the requirement of both K-Rta and the gene product of K8, K-bZIP, in the transient replication assay suggests that the initiation of HHV8 lytic replication involves transcription (1).

Although the transient replication assay was a valuable tool in the elucidation of HHV8 and other herpesvirus lytic replication origins, the assay cannot evaluate the role of each origin in the context of the viral genome. As an initial step to the introduction of specific mutations in the oriLyt regions of the HHV8 genome, we sought to evaluate the activity of each oriLyt region within the virus and go beyond the limitations of the transient replication assay. We chose to take advantage of the efficiency of generating recombinants in the backbone of the HHV8 BAC36 construct (19). Previous work using the HHV8 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) system has shown that the generation of mutants within the context of the viral genome addresses gene function and regulation in a manner that goes beyond the ability of transient systems (9, 12, 18).

In this report, we generated HHV8 BAC recombinants that lack either the rightward oriLyt (oriLyt-R nucleotides [nt] 118108 to 122139), the leftward oriLyt (oriLyt-L nt 22534 to 25665), or both oriLyt regions. Each recombinant, BAC36-ΔOri-R, BAC36-ΔOri-L, or BAC36-ΔOri-RL, respectively, was transfected into Vero cells and evaluated for its ability to propagate viral DNA. The deletion of the rightward oriLyt region, oriLyt-R, had little effect on the accumulation of viral DNA and lytic DNA synthesis. An evaluation of viral DNA synthesis mRNA levels of ORF50 (K-Rta) as well as the production of infectious virus revealed that BAC36-ΔOri-R displayed wild-type characteristics, indicating that the HHV8 genome requires only one oriLyt for growth. However, both the double deletion BAC36-ΔOri-RL and the single leftward oriLyt, BAC36-ΔOri-L, failed to propagate viral DNA or yield infectious virus.

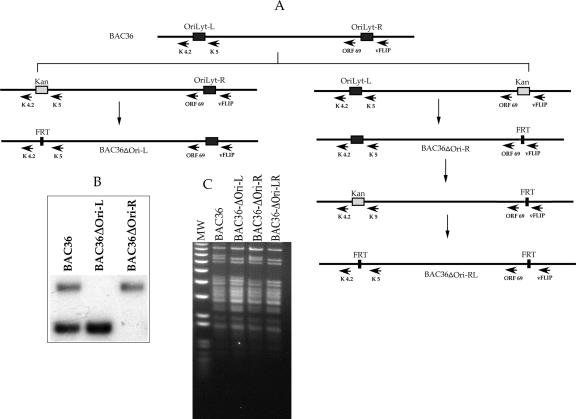

We took advantage of the Red recombination method to delete the oriLyt region within wild-type BAC36. Using this method, we first generated an HHV8 BAC recombinant containing the kanamycin resistance (Kanr) cassette in place of the oriLyt regions (Fig. 1A). The Kanr cassette was subsequently removed by the introduction of a plasmid expressing FLP recombinase, leaving only the FLP target recognition (FRT) site (Fig. 1A). The mutagenesis of HHV8 BAC36 (16), accession number U75698, was performed using Red-mediated recombination essentially as described previously (6). Escherichia coli DH10B cells harboring BAC36 DNA were transformed with the Red helper plasmid pKD46 (kindly provided by Barry Wanner, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN) containing the λ Red genes (γ, β, and exo) under the control of the arabinose-inducible promoter. The mutagenesis strategy used was the replacement of the oriLyt regions with the Kanr gene by homologous recombination and then the removal the Kanr gene by using flanking FRT sites. The Kanr gene from KD13, having the Kanr gene flanked by FRT sites, was amplified by PCR using PCR primers 70 nucleotides in length that contained 50-nucleotide homology arms at their 5′ ends and 20 nucleotides at their 3′ ends for the amplification of the Kanr gene. The PCR primers used for the generation of the oriLyt-R deletion were the C primer, 5′-CCGGGACATGAACTGCCACAAACACCGTTAAGCCTCTATCCATGCATTGGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′, and D primer, 5′-TTTCCGGCCCATCACACTCCCAACACTATCGCCATACACCATAGATAACACTGTCAAACATGAGAATTAA-3′ (the homology arms to oriLyt regions are underlined). The subsequent deletion was from nt 118108 to 122139 of the BAC genome. For the leftward deletion primers, primer A, 5′-GAGCAGCCCCAAATGTGCGCGCAACACCCAGCACATGCTCCACATACAGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′, and primer B, 5′-GAACAACCACTTGGGTGCACAGAGATATGTGACGTGACGCCCTGGGTGTTCTGTCAAACATGAGAATTAA-3′, were used.

FIG. 1.

Generation of HHV8 BAC oriLyt deletion mutants. (A) Schematic of the procedure used to generate BAC36ΔOri-L, BAC36ΔOri-R, and BAC36ΔOri-LR. The first step used the Kanr cassette to select for BAC recombinants that had either oriLyt-L (left side of the schematic) or oriLyt-R (right side of the schematic) removed and replaced with Kanr. Kanr was then removed using FLP recombinase. For the generation of the double deletion, BAC36ΔOri-R was used as the template for the insertion of Kanr, followed by the removal by FLP recombinase (lower right side). (B) Southern blot analysis of BAC36, BAC36ΔOri-R, and BAC36ΔOri-L recombinants. Purified BAC DNAs were cleaved with PstI and hybridized with 32P-labeled pDA15 plasmid. This probe will hybridize to both oriLyt regions. Lanes: 1, PstI-cleaved wild-type BAC DNA, BAC36; 2, PstI-cleaved BAC36ΔOri-L DNA; 3, PstI-cleaved BAC36ΔOri-R DNA. (C) Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel showing PstI-generated cleavage pattern of the three recombinant BAC DNAs and BAC36 DNA. MW, molecular weight.

For the construction of the BAC36-ΔOri-RL double mutant, BAC36-ΔOri-R DH10B bacteria were used as the target and primer set A and B was used for PCR amplification. Mutagenesis and selection were performed as previously described for the other BAC constructs.

For the selection of BAC36-ΔOri-L-independent isolates, the BAC mutagenesis was repeated another two times and BAC DNA was purified and used in BAC DNA transient replication experiments.

pKD46-containing BAC36 cells were induced with 1 mM arabinose and electroporated with the various PCR fragments. Colonies harboring the Camr and Kanr genes were identified on plates containing both antibiotics. After the selection of the correct recombinants and removal of the pKD46 plasmid as described previously (6), the Kanr gene was excised from the genome by transformation with the FLP expression plasmid pCD20 (kindly provided by Barry Wanner, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN) as described previously (6). Southern blot analysis and direct DNA sequencing were used to confirm the final BAC mutant.

All recombinants were initially confirmed to have the correct deletion by Southern blot analysis using the hybridization probe pDA15, a plasmid containing DNA sequences complementary to both oriLyt regions. In order to be able to detect the oriLyt deletions within the recombinant BAC DNAs, we cleaved BAC recombinants with PstI. This cleavage pattern resulted in DNA fragments that contained the entire sequence for the oriLyt regions, such that the loss of an either higher (oriLyt-L)- or lower (oriLyt-R)-molecular-weight band would signify the correct recombination event (Fig. 1B). In addition, we also separated each recombinant on an agarose gel to visually confirm that no gross DNA mutations of the HHV8 genome were introduced (Fig. 1C). Finally, all recombinants were sequenced with respect to the regions flanking the oriLyt sequences to ensure that the ORFs flanking the oriLyt loci were not removed or interrupted as a result of the recombination event.

Once we generated the HHV8 BAC recombinants, we investigated the ability of this BAC to replicate upon induction to the lytic phase. We took advantage of the fact that BAC DNA is methylated as a result of propagation in bacteria (Dam+). This allowed us to perform a transient replication assay similar to those performed with oriLyt-containing plasmid DNA. Vero cells were transfected with the BAC DNAs and then treated with an adenovirus overexpressing the viral transactivator K-Rta (ORF50) (provided by D. Ganem). Total cellular DNA was harvested at 5 days posttreatment and cleaved with EcoRI and DpnI. This protocol would allow for the detection of replicated BAC DNA since DpnI will cleave only input (methylated) BAC DNA; however, if the BAC replicates, this amplified DNA (unmethylated) becomes resistant to DpnI cleavage. Both BAC36 and BAC36-ΔOri-R displayed DpnI-resistant BAC DNA, indicating that amplification had occurred (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 4, respectively). No amplification products were visible when cells were not infected with the K-Rta-expressing adenovirus (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). This result demonstrated that the leftward oriLyt, oriLyt-L, was capable of directing the amplification of the viral genome. However, the transient transfection of the BAC recombinant BAC36-ΔOri-L resulted in the lack of detectable amplification products, even when several independently isolated BAC DNAs of BAC36-ΔOri-L were transiently transfected into Vero cells that were subsequently infected with the K-Rta-expressing adenovirus (Fig. 2A, lanes 6 to 8). These results suggested that although the leftward oriLyt alone was sufficient for viral replication, oriLyt-R did not support BAC amplification.

FIG. 2.

BAC36-Δori-L and BAC36-Δori-LR are unable to replicate BAC DNA. (A) Transient DNA replication of HHV8 BAC recombinants. Vero cells transfected with BAC36 or BAC oriLyt deletion recombinants were treated with AdKRta and evaluated for the amplification of the BAC genome using DpnI. Lanes: 1, BAC36 DNA transfected into Vero cells plus AdKRta; 2, BAC36 DNA transfected into Vero cells; 3, BAC36ΔOri-R DNA transfected into Vero cells; 4, BAC36ΔOri-R transfected into Vero cells plus AdKRta; 5, BAC36ΔOri-LIS-1 DNA transfected into Vero cells; 6, BAC36ΔOri-LIS-1 DNA transfected into Vero cells plus AdKRta; 7, BAC36ΔOri-LIS-2 DNA transfected into Vero cells plus AdKRta; 8, BAC36ΔOri-LIS-3 DNA transfected into Vero cells plus AdKRta. The arrow indicates replicated BAC DNA. (B) Recovery of BAC DNA from Vero cell lines. DNA from Vero cell lines harboring BAC36 (lane 1), BAC36ΔOri-R (lane 2), BAC36ΔOri-L (lane 3), or BAC36ΔOri-LR (lane 4) was used to transform DH10B bacteria. BAC DNA was purified from bacteria and cleaved with PstI to show the integrity of BAC DNA. (C) BAC36-Δori-L and BAC36-Δori-LR are unable to produce supernatant virus. Vero cell lines were treated with TPA, and supernatant virus was harvested at various days posttreatment and analyzed for viral DNA by qPCR. (D) BAC36 is unable to complement BAC36ΔOri-L. A Southern blot of Vero cell DNA cotransfected with either BAC36ΔOri-L (Kan) or BAC36ΔOri-R (Kan) in the presence of BAC36 and a K-Rta expression vector is shown. The amplification of the bacmid genome was detected after EcoRI and DpnI cleavage using the Kan resistance gene as a hybridization probe. Lanes: 1, BAC36, BAC36ΔOri-R (Kan) plus a K-Rta expression vector; 2, BAC36ΔOri-R (Kan) plus a K-Rta expression vector; 3, BAC36, BAC36ΔOri-L (Kan) plus a K-Rta expression vector.

In an attempt to rule out the possibility that the observed defect in replication for BAC36-ΔOri-L was due to the introduction of a mutation within an essential viral gene and not the direct result of the loss of the leftward oriLyt, we cotransfected BAC36-ΔOri-L along with BAC36 and again assayed for BAC36-ΔOri-L BAC amplification. Three cotransfections were performed. The first used BAC36-ΔOri-R containing the Kan cassette, BAC36 (no Kan present), and a K-Rta expression plasmid (Fig. 2D, lane 1). The second contained BAC36-ΔOri-R containing the Kan cassette and a K-Rta expression plasmid (Fig. 2D, lane 2). The third contained BAC36-ΔOri-L containing the Kan cassette, BAC36, and a K-Rta expression plasmid (Fig. 2D, lane 3). Total cell DNA was harvested 5 days posttransfection and cleaved with EcoRI and DpnI. Southern blots were prepared, and the amplification of BAC DNAs was detected using the Kan resistance gene as a hybridization probe. Since BAC36 is replication competent, it should complement any trans genetic defect in BAC36-ΔOri-L. The result of the cotransfection experiment showed that BAC36 could not complement the amplification of BAC36-ΔOri-L (Kan), suggesting that the defect is due to the lack of the cis-acting oriLyt-L sequence (Fig. 2D, lane 3).

We also examined the amount of infectious virus produced in the supernatant of cell lines harboring BAC recombinants. The relative amount of supernatant virus was determined by treating Vero cells harboring BAC DNAs with tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (TPA) for 48, 72, 96, or 120 h. Cell supernatants were collected at each time point and subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Viral DNA was pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 15 min), and DNA was resuspended in 20 μl of Tris-EDTA. The relative amount of viral DNA was measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using a latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA)-specific probe and primers. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the relative amount of DNA was compared to that for untreated BAC36 supernatants. The results were consistent with what was observed from the studies performed to investigate the amplification of the recombinant BAC genomes. Similar increases in supernatant viral DNA were observed from cells containing BAC36 and BAC36-ΔOri-R (Fig. 2C). However, no increase in viral supernatant DNA was observed in BAC36-ΔOri-L- or BAC36-ΔOri-RL-containing cells treated with TPA (Fig. 2C). This result indicated that these BAC recombinants were unable to produce infectious virus.

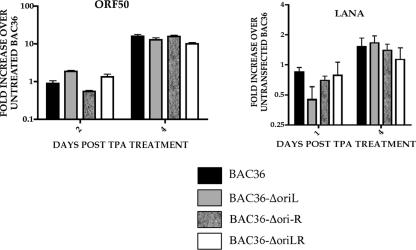

In order to evaluate the relative gene expression pattern of BAC oriLyt deletion mutants compared to that of BAC36, we measured ORF50 mRNA levels in cells harboring BAC DNAs. For the measurement of ORF50 mRNA, cells were induced with TPA (25 ng/ml) and qPCR was performed at 2 or 4 days posttreatment. Total cellular RNA was isolated 2 or 4 days posttransfection using TRIzol (Invitrogen) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples were treated with 10 U of DNase I (Ambion) prior to the generation of cDNA. qPCR primers and probes used to detect specific HHV8 transcripts (ORF50 and LANA) have been described previously (18). qPCR was carried out as previously described, and data were analyzed according to Amersham Biosystems User Bulletin no. 2 (P/N 4303859) by using a derivation of the 2−ΔΔCT method using untreated BAC-containing cells as control samples (11). Each experiment was repeated at least six times, and mRNA levels were measured in triplicate. Data are reported such that test samples were compared to RNA levels observed from untreated BAC36 cells. Similar ORF50 mRNA levels were observed for all BAC recombinants and BAC36-containing cell lines (Fig. 3). As an additional control for the normalization of viral mRNAs, we measured the accumulation of LANA mRNA. This transcript should be relatively unaffected by the replicative state of resident BAC viral DNA. As expected, the accumulation of LANA mRNA was similar in cells containing BAC36 and oriLyt deletion BACs (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of ORF50 and LANA mRNA accumulation in BAC oriLyt deletion mutants by qPCR. Vero cells containing BAC oriLyt mutant recombinants were treated with TPA, and total cellular RNA was analyzed for viral transcript accumulation using qPCR. Error bars indicate standard deviations from six separate experiments.

In this report, we demonstrate that the Red recombination method is a viable method to alter the genome of HHV8 using the available BAC construct BAC36. Recently the Red recombination method was successfully used to introduce and study gene expression of a mutated open reading frame in murine cytomegalovirus as well as a variety of other herpesvirus systems in the context of the viral genome (3). In our hands, this method proved to be a simple technique to manipulate the HHV8 genome in the context of the BAC construct.

Our results show that oriLyt-L alone is sufficient to propagate the HHV8 genome. Although it was shown that in the transient assays for HHV8 oriLyt-L and oriLyt-R function in an equivalent manners, the data presented here emphasize the importance of studying the activity of cis-acting sequences like lytic origins within the context of the virus genome.

The deletion of oriLyt-R from the viral genome does not appear to effect viral gene expression or DNA synthesis. Based on the data presented here, we conclude that oriLyt-R is not required for DNA synthesis in the context of the viral genome. The deletion of oriLyt-R also removes several previously described microRNAs (4, 5, 8, 15). It appears that these microRNAs, along with the cis-acting oriLyt-R, are dispensable for viral replication. oriLyt-L alone is sufficient to direct lytic DNA replication in a manner similar to that observed with wild-type BAC. This result is consistent with laboratory strain of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and the genome of the closely related rhesus monkey rhadinovirus, where only one lytic origin is sufficient to direct replication (14).

A somewhat surprising result is the failure of the BAC with oriLyt-L deleted to support viral replication. The deletion of oriLyt-L also removes an identified open reading frame within this region (17). This could be one explanation for the null phenotype observation; however, we attempted to complement the oriLyt-L BAC deletion by transfecting plasmids that contained both the deleted region and large regions flanking the oriLyt-L loci. We were unable to restore a replication-competent phenotype by the transfection of these plasmids (data not shown). In order to increase the confidence of our result, we remade the BAC36-ΔOri-L BAC several times and tested these independent isolates for the accumulation of viral DNA (Fig. 2). None of these independent isolates supported DNA replication.

The presence of two origins within HHV8 is not unlike that within some clinical strains of EBV, whereas the laboratory strain of EBV (B95-8) contains only one lytic origin. The replication of the EBV genome also displayed somewhat different properties than those observed in transient replication assays when the oriLyt sequence was mutated within the context of the viral genome (7).

Our next step will be to introduce targeted mutations into the oriLyt-L region within the viral genome. These mutations will allow for the correlation of lytic origin activity observed from the transient replication assay. This will be carried out in an attempt to determine whether essential regions elucidated from the transient assay directly translate to requirements within the context of the viral genome. Now that it is established that only one oriLyt region is necessary for efficient propagation of the HHV8 viral genome, it is possible to concentrate on the oriLyt-L region for future genetic manipulations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R01 CA085164.

REFERENCES

- 1.AuCoin, D. P., K. S. Colletti, S. A. Cei, I. Papouskova, M. Tarrant, and G. S. Pari. 2004. Amplification of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 lytic origin of DNA replication is dependent upon a cis-acting AT-rich region and an ORF50 response element and the trans-acting factors ORF50 (K-Rta) and K8 (K-bZIP). Virology 318:542-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AuCoin, D. P., K. S. Colletti, Y. Xu, S. A. Cei, and G. S. Pari. 2002. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) contains two functional lytic origins of DNA replication. J. Virol. 76:7890-7896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bubeck, A., M. Wagner, Z. Ruzsics, M. Lotzerich, M. Iglesias, I. R. Singh, and U. H. Koszinowski. 2004. Comprehensive mutational analysis of a herpesvirus gene in the viral genome context reveals a region essential for virus replication. J. Virol. 78:8026-8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai, X., and B. R. Cullen. 2006. Transcriptional origin of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs. J. Virol. 80:2234-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai, X., S. Lu, Z. Zhang, C. M. Gonzalez, B. Damania, and B. R. Cullen. 2005. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:5570-5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feederle, R., and H. J. Delecluse. 2004. Low level of lytic replication in a recombinant Epstein-Barr virus carrying an origin of replication devoid of BZLF1-binding sites. J. Virol. 78:12082-12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundhoff, A., C. S. Sullivan, and D. Ganem. 2006. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12:733-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan, H. H., N. Sharma-Walia, L. Zeng, S. J. Gao, and B. Chandran. 2005. Envelope glycoprotein gB of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is essential for egress from infected cells. J. Virol. 79:10952-10967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin, C. L., H. Li, Y. Wang, F. X. Zhu, S. Kudchodkar, and Y. Yuan. 2003. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic origin (ori-Lyt)-dependent DNA replication: identification of the ori-Lyt and association of K8 bZip protein with the origin. J. Virol. 77:5578-5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luna, R. E., F. Zhou, A. Baghian, V. Chouljenko, B. Forghani, S. J. Gao, and K. G. Kousoulas. 2004. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus glycoprotein K8.1 is dispensable for virus entry. J. Virol. 78:6389-6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholas, J., J. C. Zong, D. J. Alcendor, D. M. Ciufo, L. J. Poole, R. T. Sarisky, C. J. Chiou, X. Zhang, X. Wan, H. G. Guo, M. S. Reitz, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Novel organizational features, captured cellular genes, and strain variability within the genome of KSHV/HHV8. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 23:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pari, G. S., D. AuCoin, K. Colletti, S. A. Cei, V. Kirchoff, and S. W. Wong. 2001. Identification of the rhesus macaque rhadinovirus lytic origin of DNA replication. J. Virol. 75:11401-11407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer, S., A. Sewer, M. Lagos-Quintana, R. Sheridan, C. Sander, F. A. Grasser, L. F. van Dyk, C. K. Ho, S. Shuman, M. Chien, J. J. Russo, J. Ju, G. Randall, B. D. Lindenbach, C. M. Rice, V. Simon, D. D. Ho, M. Zavolan, and T. Tuschl. 2005. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat. Methods 2:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X. P., Y. J. Zhang, J. H. Deng, H. Y. Pan, F. C. Zhou, and S. J. Gao. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded oncogene viral interferon regulatory factor by a novel transcriptional silencer, Tis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12023-12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang, Y., H. Li, M. Y. Chan, F. X. Zhu, D. M. Lukac, and Y. Yuan. 2004. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ori-Lyt-dependent DNA replication: cis-acting requirements for replication and ori-Lyt-associated RNA transcription. J. Virol. 78:8615-8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, Y., D. P. AuCoin, A. R. Huete, S. A. Cei, L. J. Hanson, and G. S. Pari. 2005. A Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 ORF50 deletion mutant is defective for reactivation of latent virus and DNA replication. J. Virol. 79:3479-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou, F. C., Y. J. Zhang, J. H. Deng, X. P. Wang, H. Y. Pan, E. Hettler, and S. J. Gao. 2002. Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome: application for genetic analysis. J. Virol. 76:6185-6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]