Abstract

Cytosolic division in mitotic cells involves the function of a number of cytoskeletal proteins, whose coordination in the spatio-temporal control of cytokinesis is poorly defined. We studied the role of p85/p110 phosphoinositide kinase (PI3K) in mammalian cytokinesis. Deletion of the p85α regulatory subunit induced cell accumulation in telophase and appearance of binucleated cells, whereas inhibition of PI3K activity did not affect cytokinesis. Moreover, reconstitution of p85α-deficient cells with a Δp85α mutant, which does not bind the catalytic subunit, corrected the cytokinesis defects of p85α−/− cells. We analyzed the mechanism by which p85α regulates cytokinesis; p85α deletion reduced Cdc42 activation in the cleavage furrow and septin 2 accumulation at this site. As Cdc42 deletion also triggered septin 2 and cytokinesis defects, a mechanism by which p85 controls cytokinesis is by regulating the local activation of Cdc42 in the cleavage furrow and in turn septin 2 localization. We show that p85 acts as a scaffold to bind Cdc42 and septin 2 simultaneously. p85 is thus involved in the spatial control of cytosolic division through regulation of Cdc42 and septin 2, in a PI3K-activity independent manner.

Keywords: cell cycle, cytokinesis, p85 regulatory subunit, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Introduction

Cell division ends with the processes of nuclear division and cytosolic separation (cytokinesis). Cytosolic division occurs when DNA separation terminates. Preparation for cytokinesis nonetheless begins in metaphase, with selection of the division site at the cell center (cleavage plane specification), continues in anaphase, with recruitment of proteins to the cleavage furrow, and finishes in telophase, with formation of the contractile actomyosin ring and abscission of the intracellular bridge.

Cytokinesis requires cooperation of cytoskeletal components such as actin and myosin, which concentrate at the borders of the cytokinetic furrow, as well as tubulin, which forms the midzone microtubule (MT) structure (Straight and Field, 2000). Another cytoskeletal component that regulates cytokinesis is the septin family of guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, which form filaments and associate with actin and/or tubulin in the cleavage furrow (Surka et al, 2002, reviewed by Kinoshita, 2003). Cytokinesis is also controlled by small GTPases of the Rho family such as RhoA, which regulates the actin cytoskeleton (Mishima et al, 2002). Cdc42 also controls actin and septin cytoskeletons in interphase (Joberty et al, 2001), and regulates septin ring formation during yeast cytokinesis (Caviston et al, 2003). Although many cytokinesis regulators are known, the mechanism controlling the time and place of mammalian cytokinesis is poorly understood.

Here we studied the contribution of p85/p110 class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) to mammalian cytokinesis. The class IA PI3K are dual specificity lipid and protein kinases composed of a catalytic subunit (p110α, β, or δ) and a regulatory subunit (p85α, p85β, or p55γ), which catalyze formation of 3-poly-phosphoinositides (PIP3) following Tyr kinase stimulation (Vanhaesebroeck and Waterfield, 1999). The regulatory subunit p85 also controls cell responses by regulating activation of signaling molecules such as Cdc42 in a PI3K activity-independent manner (Jiménez et al, 2000).

PI3K activity increases early in M phase to regulate mitosis entry in several cell types, more markedly in epithelial cells (Shtivelman et al, 2002; Dangi et al, 2003). We previously showed that increased p85α expression diminishes PI3K activity, reducing S phase entry, but accelerating the M-to-G1 transition (Alvarez et al, 2001). This suggests a p85α contribution to cell cycle termination.

We show that deletion of p85α induces cell accumulation in telophase, delayed cytokinesis, and appearance of binucleated cells. These defects were not observed following inhibition of PI3K activity. Cytokinesis was restored by reconstitution of the cells with Δp85, a mutant that does not bind the p110 catalytic subunit (Hara et al, 1994). Considering that p85α associates with and regulates Cdc42 in a PI3K-independent manner during interphase (Jiménez et al, 2000), we examined whether p85α also controls Cdc42 in mitosis. p85α deletion diminished Cdc42-GTP levels, and impaired its cleavage furrow localization in cytokinesis. We show that defects in either p85α or Cdc42 affect septin organization in telophase. Finally, we examined p85 association with Cdc42 and septin 2 during cytokinesis. We present data illustrating a novel PI3K activity-independent p85α function in mammalian cytokinesis.

Results

Cytokinesis defects in p85α-deficient fibroblasts

To study the role of PI3K in mitosis, we examined the phenotype of p85α-deficient cells. p85α−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) showed higher p85β expression levels than wild type (WT) cells (Figure 1A). As p85α is more abundant than p85β (Ueki et al, 2002), however, total p85 levels were still notably lower in p85α−/− MEF (Figure 1A). p85α−/− cells had lower p110α and nearly normal p110β levels (Figure 1A).

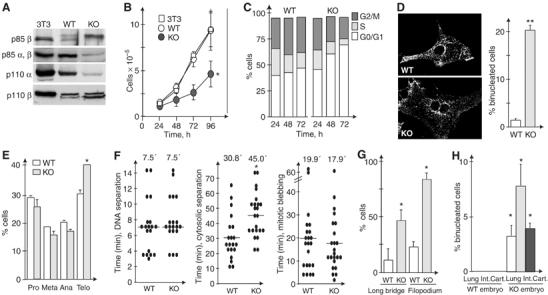

Figure 1.

Cytokinesis defects in p85α-deficient cells. (A) Expression of PI3K subunits in NIH3T3 cells, WT, and p85α−/− MEF. p85β expression was examined by specific immunoprecipitation followed by WB with anti-p85 Ab (top). Total p85, p110α, and p110β expression levels were analyzed by WB with specific Ab. (B) NIH3T3 cells, WT, and p85α−/− MEF (used immediately after preparation) were seeded at similar densities and counted at 24 h intervals. Mean of five assays. (C) Percentage of WT and p85α−/− MEF (as in A) in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases. (D) Representative image of WT and p85α−/− MEF stained with anti-pan-cadherin and percentage of binucleated cells in WT and p85α−/− MEF cultures. (E) Percentage of cells at different mitosis stages (100% total mitotic cell count). Mean±s.d. of four experiments. (F) Time required for mitotic events (indicated). Mean time is included. Each dot represents an independent cell video. (G) Percentage of cells showing persistent filopodia or long intracellular bridges. (H) Binucleated cells in sections of lung, small intestine (int), and cartilage (cart) from WT and p85α−/− E14.5 embryos. Statistical significance was calculated by comparing mean values of at least three experiments performed with different WT and p85α−/− MEF lines. Student's t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.001. Bar=10 μm.

Proliferation was slower in p85α−/− MEF than in WT cells, as estimated by cell counting (Figure 1B) and [3H]-Thy incorporation (not shown). Accordingly, cell cycle distribution at different times after seeding showed a larger proportion of G0/G1 cells in p85α−/− cultures than in WT MEF (Figure 1C). The decreased PI3K activity in p85α−/− cells (∼50%; Ueki et al, 2003) explains the slower division of p85α−/− MEF, as PI3K activity regulates cell cycle entry (Álvarez et al, 2001). The most striking observation in p85α−/− cultures was the larger proportion of binucleated cells compared to controls. Whereas NIH3T3 (not shown) and WT MEF cultures had a maximum of 1% binucleated cells, approximately 20% of p85α−/− MEF were binucleated (Figure 1D). A larger proportion of p85α−/− MEF were in telophase compared to WT cells (Figure 1E), suggesting slower progression through this phase.

We then recorded WT and p85α−/− prometaphase cells by phase-contrast videomicroscopy (Supplementary videos 1, 2 and 3 and Supplementary legends, representative videos, n=30/cell type). We measured the time required for DNA separation, considered as the interval from metaphase plate formation until early telophase (visualized by cleavage furrow emergence, immediately after anaphase). In some videos, we observed cell rounding and detachment during recording indicative of mitosis initiation, which allowed determination of the time from cell rounding to metaphase plate formation. We also estimated cytosolic division time, considered as the interval from early telophase to abscission. Cytosolic separation was slower in p85α−/− than in WT MEF (Figure 1F), confirming p85α involvement in cytokinesis. We detected no evident DNA separation defects in p85α−/− MEF, and its duration was similar in both cells (∼7.5 min; Figure 1F). Metaphase plate formation was slower in p85α−/− than WT MEF (10.18±2.81 versus 4.8±1.05 min, respectively).

Defects in RhoA downregulation induce abnormal cortical activity during cytokinesis, manifested by increased mitotic blebbing (Prothero and Spencer, 1968), which correlates with appearance of micronuclei (Lee et al, 2004). Mitotic blebbing was similar in WT and p85α−/− MEF. Approximately 15% of cells showed little or no blebbing; a similar percentage showed high-intensity blebbing, and remaining cells showed intermediate blebbing in both cell types. Bleb location and duration were similar in WT and p85α−/− MEF (Figure 1F). Nonetheless, ∼43% of p85α−/− and ∼26% of WT MEF (n=30) formed large blebs that resembled ectopic contractions (Supplementary videos 1 and 3). Micronuclei (examined by DNA staining) were seen in ∼4% of both cell types. p85 deficiency thus does not induce marked alterations in cortical integrity as do RhoA, tropomyosin, or myosin defects (Lee et al, 2004). Of the p85α−/− MEF videos examined (n=30), one showed apoptosis after detachment, and two showed virtual cytokinesis failure, with furrow formation and subsequent regression (not shown). In addition, ∼40% of p85α−/− cells developed very long furrows (Supplementary video 2), a phenotype seen in only ∼10% of mitotic WT MEF (Figure 1G). Moreover, WT MEF formed filopodium-like structures at pro-metaphase and in telophase immediately before reattachment, but p85α−/− cells showed these structures throughout mitosis (Figure 1G).

p85α−/− mice die at birth (Fruman et al, 1999). To analyze cytokinesis defects in vivo, we compared binucleated cell numbers in WT and p85α−/− embryos at developmental day E14.5. In a variety of tissues, the proportion of binucleated cells was larger in p85α−/− than in WT embryos (Figure 1H; 4.9±2.4 versus 0.2±0.5%, respectively; P<0.05), confirming p85α involvement in cytokinesis control.

PI3K inhibition does not affect cytokinesis

To examine the role of PI3K activity in cytokinesis, we analyzed PI3K activation during mitosis. NIH3T3 cells synchronized in G0 were examined at different times after serum addition (Martinez-Gac et al, 2004). Cells were also arrested in G2 phase by etoposide treatment, or in metaphase using colcemid, a MT-depolymerizing agent. Cells can re-establish metaphase following colcemid removal. We examined PI3K activity by measuring phosphorylation of its effector PKB (Álvarez et al, 2001). pPKB increased in G1 and when cells re-established metaphase, 1 h after colcemid removal (Figure 2A and B).

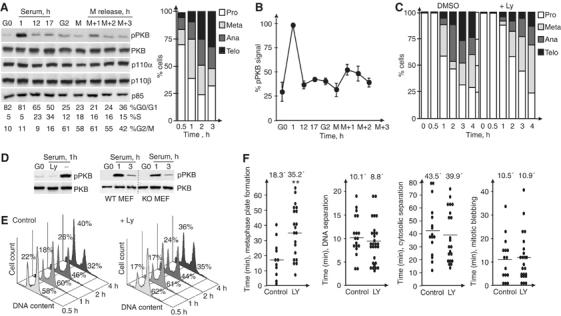

Figure 2.

PI3K inhibition does not interfere with cytokinesis. (A) NIH3T3 cells were arrested in G0 and released in serum, or were arrested in G2 or in metaphase (M), and released for different periods. Extracts (40 μg) were examined in WB using appropriate Ab. Cell samples were examined to control progression through mitotic phases (as in Figure 1E). (B) Percentage of phospho-PKB examined as in (A), compared to maximum pPKB signal at 1 h after serum addition (100%). Mean±s.d. of three experiments. (C) Cells were arrested in metaphase and a fraction was treated with Ly294002 1 h before and after colcemid withdrawal. Percentage of cells in different mitosis phases. (D) NIH3T3 cells, WT, and p85α−/− MEF were serum-starved, preincubated alone or with Ly294002 (1 h), and then stimulated with serum (1 h). pPKB was examined by WB. (E) Cell cycle distribution after colcemid removal (as in C), in control and Ly294002-treated cells (%G0/G1 and G2/M indicated). Binucleated cells 6 h after colcemid removal was ∼1% in control and Ly294002-treated cells. (F) NIH3T3 cells were arrested by serum deprivation and released for 17 h with serum; Ly294002 was then added (1 h) and cultures examined as in Figure 1F. **P<0.001.

We studied the consequences on cytokinesis of interfering PI3K activity using the PI3K inhibitor Ly294002. NIH3T3 cells were synchronized in G0 as above. PI3K inhibition at 12 h postserum addition (∼30% cells in S phase) delayed mitotic entry by 2 h (not shown), as reported (Shtivelman et al, 2002). Nonetheless, PI3K inhibition did not increase the proportion of telophase cells (not shown) or the percentage of binucleated cells (∼1%, with and without Ly294002). We also arrested cells in metaphase and released them, alone or with Ly294002. PI3K inhibition delayed metaphase, but did not cause cell accumulation in telophase (Figure 2C) or appearance of binucleated cells (∼1%, alone or with Ly294002). We confirmed the efficiency of PI3K inhibition in parallel by analyzing pPKB in a cell fraction treated with Ly294002 (1 h), then stimulated with serum (1 h). PI3K/PKB inhibition by Ly294002 treatment was greater than that observed by p85α deletion (Figure 2D). Control and Ly294002-treated cells exited cell cycle at a similar rate (Figure 2E).

We examined the consequences of PI3K inhibition in cytokinesis by phase-contrast videomicroscopy. NIH3T3 cells, synchronized in G0 and released as above, were treated with vehicle or Ly294002 at 17 h postserum addition (∼50% in S/G2/M) and recorded 1 h later, as above. PI3K inhibition delayed metaphase plate formation (Figure 2F) more markedly than p85α deletion (Figure 1), confirming a contribution of PI3K activity in early mitosis (Dangi et al, 2003). Cells nonetheless progressed to subsequent mitotic phases, and we detected no significant differences in mitotic blebbing, DNA or cytosolic separation times (Figure 2F), supporting the idea that PI3K inhibition does not interfere with cytokinesis.

Inhibition of PI3K in metaphase yielded comparable results (not shown). Ly294002 treatment of HeLa human epithelioid carcinoma cells exiting from metaphase (as above) did not induce cell accumulation in telophase, and only slightly increased the proportion of binucleated cells (∼3 versus ∼1% in untreated controls). Thus, PI3K inhibition did not delay DNA or cytosolic separation, and induced neither cell accumulation in telophase nor appearance of binucleated cells.

Cdc42 and p85 localization in mitosis

To identify the mechanism by which p85α operates in cytokinesis, we considered that p85 regulates Cdc42 activity, and that molecule controls cell separation (Jiménez et al, 2000); we postulated that p85 may act in cytokinesis by regulating Cdc42.

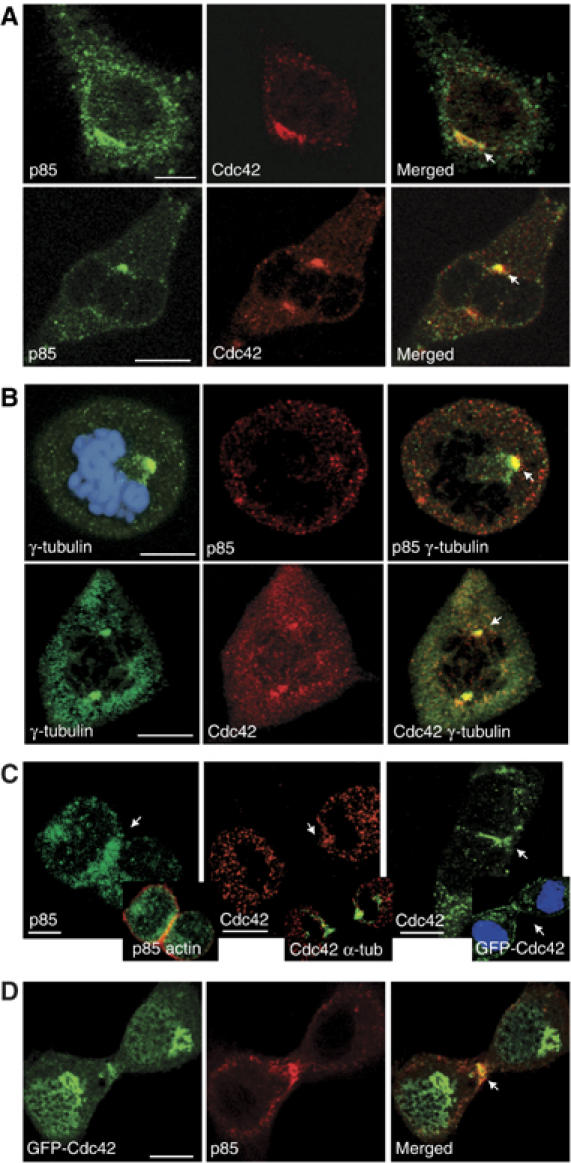

We examined p85 and Cdc42 localization by immunofluorescence, using specific antibodies (Ab). In interphase, p85 localized throughout cytoplasm in vesicle-like structures, while most Cdc42 concentrated in a discrete region (Figure 3A), the Golgi (not shown; Erickson et al, 1996). A fraction of p85 colocalized with Cdc42 in interphase (Figure 3A). In metaphase, p85 and Cdc42 distributed in vesicles, and colocalized (>90% of the cells) in a position near centrosomes (Figure 3A), as determined by simultaneous staining with γ-tubulin (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Cdc42 and p85 localization in mitosis. (A) Simultaneous p85 and Cdc42 staining in interphase (top) or metaphase cells (bottom). (B) Simultaneous p85 or Cdc42 and γ-tubulin staining. DNA staining is shown in the top image. (C) p85 immunofluorescence (left) and colocalization with actin (inset). Localization of Cdc42 (middle) and simultaneous analysis of Cdc42 and α-tubulin (inset). Analysis of Cdc42 (left) and GFP-Cdc42 distribution (inset, DNA staining). (D) Colocalization of GFP-Cdc42 with p85, examined by immunofluorescence. (A–D) NIH3T3 cells. Arrow indicates the region where p85 and/or Cdc42 concentrate near centrosomes or cleavage furrow. Bar=10 μm. DNA staining was examined in all samples, and included in some images when required to illustrate the mitosis phase of the cell.

In telophase, p85 still exhibits a vesicular localization and in ∼50% of the cells a fraction of it concentrates at the cleavage furrow (Figure 3C, left). Cdc42 localization in telophase was also vesicular. Telophase images showed Cdc42 vesicles throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 3C, middle and right), in the nascent Golgi (Figure 3D), and in ∼60% of the cells in the cleavage furrow (Figure 3C, middle and right, and D), near central spindle MT (Figure 3C, middle). Similar to endogenous Cdc42, GFP-Cdc42 was found at nascent Golgi and the cleavage furrow, with the exception of a nonspecific GFP-Cdc42 nuclear localization (Figure 3C, right inset and D). Thus, both Cdc42 and p85 localized, at least transiently, to the cleavage furrow in telophase. Simultaneous staining of p85 and Cdc42 (not shown) and p85 staining in cells expressing GFP-Cdc42 suggested physical proximity of these molecules at the cleavage furrow during telophase (in ∼60% of images; Figure 3D).

Defective Cdc42 activation in p85α-deficient cells

To quantitate Cdc42 activation in WT and p85α−/− MEF, we measured Cdc42-GTP in pull-down assays (Jiménez et al, 2000). Cells were arrested in metaphase, then released to obtain cultures enriched in different mitotic phases. Cdc42-GTP levels fluctuated during mitosis progression in WT MEF. High Cdc42-GTP levels were found in metaphase-enriched WT cultures (Figure 4A and B), concurring with other studies (Oceguera-Yanez et al, 2005). In addition, Cdc42-GTP increased systematically 3 h after colcemid removal in WT MEF, when the most abundant mitotic phase is telophase (Figure 4A and B). In p85α−/− cells, metaphase re-establishment was slower than in controls, but cells reached telophase normally (Figure 4B); Cdc42-GTP levels were always greatly reduced in p85α−/− MEF (Figure 4A).

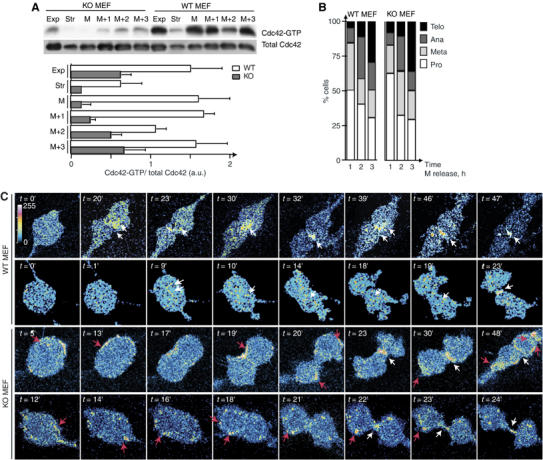

Figure 4.

Cdc42-GTP cleavage furrow localization in WT, but not p85α−/− MEF. (A) WT and p85α−/− MEF were serum-starved (Str), cultured to exponential growth (Exp), or arrested in metaphase (M) by mild colcemid treatment, then released for different periods. Extracts were analyzed in pull-down assays using Gex2T-CRIBN-WASP as bait. Cdc42-GTP and total Cdc42 cell content was examined by WB. A representative experiment of three is shown. Quantitative analysis of Cdc42-GTP normalized to total Cdc42. (B) Mitosis phases were examined in a fraction of the cells from (A). (C) WT and p85α−/− MEF expressing CFP-CRIBN-WASP were examined in time-lapse confocal video microscopy. Images are from two representative videos of each type (n=30). The time of image collection from the beginning of recording (∼pro-metaphase t=0) is indicated. Images are shown in false color scale to illustrate relative distribution of the probe. White arrows show the normal of Cdc42-GTP itinerary in WT cells and its final localization at the cleavage furrow in both MEF types, red arrows ectopic Cdc42-GTP localization in p85α−/− cells.

As active Cdc42 levels were reduced but not abrogated in p85α−/− cells, we examined whether Cdc42-GTP was appropriately localized in p85α−/− MEF. We tracked Cdc42-GTP location by monitoring cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fused to CRIBN-WASP (Figure 4C; Supplementary video 4 including a WT and a p85α−/− cell; n=30/cell type), which selectively binds Cdc42-GTP (Miki et al, 1998; Benink and Bement, 2005). We also examined Pak-1 CRIB domain distribution in mitotic cells (Supplementary video 5, a WT and a p85α−/− cell; n=25/cell type). Although Pak-1 binds both Rac-1-GTP and Cdc42-GTP, Rac-1 is not active in telophase (Oceguera-Yanez et al, 2005). Expression of CRIB constructs by retroviral infection yielded uniform expression levels in p85α−/− and WT MEF, and did not alter mitosis timing compared to uninfected controls (not shown). Video microscopy of WT MEF showed the CRIB probe concentrated at the inner region of the cleavage furrow (Figure 4C; Supplementary videos 4 and 5). The analysis suggested dynamic Cdc42-GTP behavior, as images of CRIBN-WASP at the midzone MT region alternate with images of CRIBN-WASP at the furrow (Figure 4C). In contrast, CRIB concentrates at the cell membrane in p85α−/− MEF, from which it eventually arrives at the cleavage furrow (Figure 4C; Supplementary videos 4 and 5).

Mitotic blebbing was similar to that in uninfected cells; large membrane protrusions were present at higher frequency in p85α−/− MEF; CFP-CRIBN-WASP localized at these protuberances. However, in WT MEF, mitotic blebbing was detected only in phase-contrast (Supplementary video 6), as CFP-CRIBN-WASP localizes at an inner cell structure, making it difficult to delimit cell membrane. The defective Cdc42-GTP distribution in p85α−/− cells correlates with defective cytokinesis in these cells.

Septin 2 localization defects in p85α−/− fibroblasts

As Cdc42 regulates the septin cytoskeleton during yeast mitosis (Kinoshita, 2003), we examined whether p85, which controls Cdc42, regulates mitotic septin 2 organization.

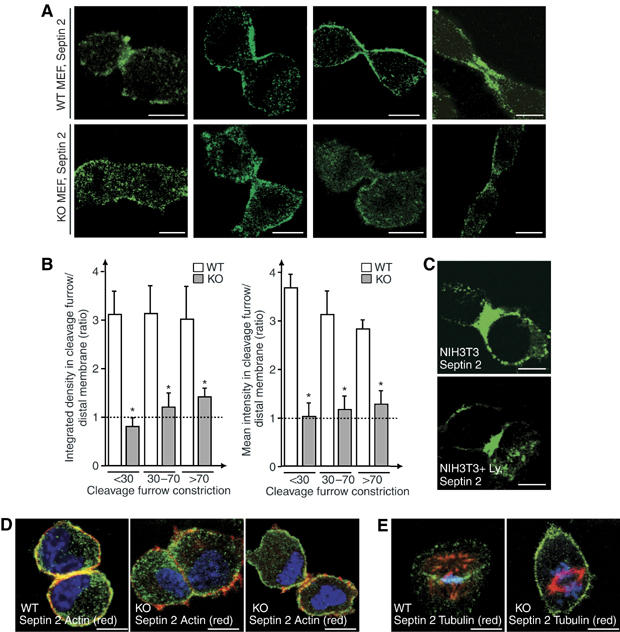

Septin 2 localization in MEF (Figure 5) was similar to that in HeLa cells (Surka et al, 2002). Septin 2 distribution was clearly disrupted in p85α−/− MEF (Figure 5A). Septin 2 stained the division plane in metaphase (see below), and concentrated in the cytokinesis furrow in telophase WT MEF (Figure 5A). In contrast, in p85α−/− MEF, septin 2 concentrated at the metaphase division plane in only ∼50% of cells, and did not localize to the cleavage furrow in most telophases (>75%; Figure 5A). Quantitation of the septin 2 signal in the cleavage furrow and distal cell membrane confirmed that whereas the septin 2 signal in the cleavage furrow is greater than that at distal membrane in WT cells, in p85α−/− MEF the signal is lower, and of comparable magnitude in the furrow and distal membrane regions (Figure 5B). PI3K inhibition in early mitosis did not alter septin 2 localization in telophase (∼85%) (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Septin localization in WT and p85α-deficient cells. (A) Septin 2 localization in WT and p85α−/− MEF (indicated). Mitotic cells were identified by simultaneous DNA staining (not shown). (B) The total integrated septin 2 signal (left panel) was measured in the cleavage furrow region and distal cell membrane, the figure illustrates the ratio of these values. The signal per area unit (right panel) was examined and plotted similarly. *P<0.05. The X-axis indicates the percentage of furrow constriction in the cells examined, compared to maximal constriction at abscission (100%). (C) NIH3T3 cells arrested in metaphase were incubated alone or with Ly294002 during release from metaphase arrest (6 h), then fixed and stained with anti-septin 2 Ab. (D, E) Simultaneous staining of septin 2, DNA, and either actin (D) or α-tubulin (E). Labeling and image collection was similar in both MEF. Bar=10 μm. (A, C–E) show representative images.

Actin and septin 2 colocalize in the WT MEF cleavage furrow (Figure 5D). Actin also concentrates in the cleavage furrow in p85α−/− MEF (∼70%) with a lower intensity than in WT cells (∼30%) and localizes in filopodium-like structures in p85α−/− MEF (∼70%; Figure 5D). This phenotype may be caused by Cdc42-GTP membrane localization in p85α−/− MEF, as Cdc42-GTP triggers filopodium formation (Jiménez et al, 2000). The tubulin cytoskeleton showed no notable defects in p85α−/− MEF (not shown). The mitotic spindle was incorrectly located in a small proportion of metaphase p85α−/− cells (∼8 versus 2% in WT MEF, P<0.05; Figure 5E), and some showed unattached chromatids (∼7 versus 2% in WT MEF, P<0.05). Micronuclei were found in ∼4% of both cell types. p85α deficiency thus results in cytokinesis and septin 2 distribution defects, but fewer defects in DNA separation and in actin/tubulin.

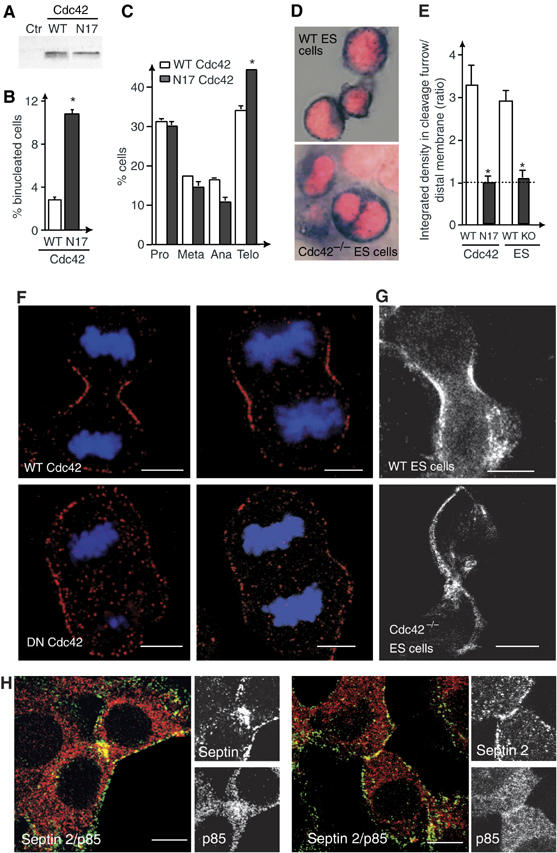

Interference with Cdc42 induces septin 2 localization defects

The hypothesis that p85α regulates cytosolic division by affecting the activity of Cdc42, a molecule that controls septin dynamics during yeast mitosis (Kinoshita, 2003), anticipates that interference with endogenous Cdc42 may induce septin 2 localization defects in MEF. Expression of a dominant-negative Cdc42 mutant (N17-Cdc42; Jiménez et al, 2000; Figure 6A) in NIH3T3 cells induced appearance of binucleated cells and increased the proportion of cells in telophase (Figure 6B and C). Although Cdc42 deficiency is embryonic lethal, Cdc42−/− embryonic stem cells (ES) are viable (Chen et al, 2000). A significant proportion of Cdc42−/− ES cells were binucleated (>12 versus <1% control ES cells; Figure 6D). Moreover, both expression of N17-Cdc42 (>65% of cells; Figure 6F) and Cdc42-deletion (>80%; Figure 6G) reduced the amount of septin 2 localized at the cleavage furrow (Figure 6E). Interference with Cdc42 function thus affects septin 2 localization in telophase.

Figure 6.

Interference with Cdc42 activation or expression impairs cytokinesis and septin 2 localization. (A–C) NIH3T3 cells were transfected with WT- or N17-Cdc42. We examined expression levels (A), percentage of binucleated cells (B) and percentage of cells at different mitotic phases (C). Mean±s.d. of four experiments. (D) DNA staining and cytosolic alkaline phosphatase activity was examined in control and Cdc42−/− ES cells. (E) The relative septin 2-signal intensity in the cleavage furrow was examined as in Figure 5B. NIH3T3 cells expressing WT or N17-Cdc42 as well as WT or Cdc42−/− ES cells are compared (Mean of 30 images). (F, G) Immunofluorescence analysis of septin 2 in control and N17-Cdc42-expressing NIH3T3 cells (E), or in control and Cdc42−/− ES cells (F). Labeling and recording in the samples were similar. (H) Colocalization of p85 and septin 2 immunofluorescence signal in NIH3T3 cells. Merged images show co-localization. Bar=10 μm. *P<0.05.

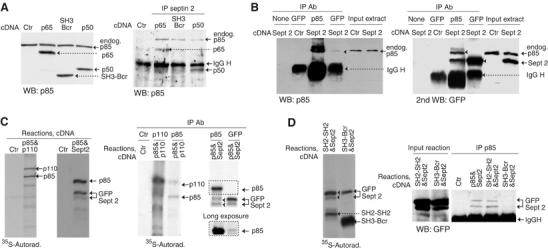

p85 associates with septin 2

We showed that p85 deletion reduced Cdc42-GTP levels in the cleavage furrow and diminished septin 2 at this site. As Cdc42 controls septin organization in mitosis (Figure 6), it appears that p85 regulates Cdc42 activation and septin 2 in a sequential manner. Since p85 associates with Cdc42 (Jiménez et al, 2000), and a fraction of p85 colocalizes with septin 2 in interphase (unpublished results), we examined whether p85 might link Cdc42 and septin 2.

We first examined p85 association with septin 2. Immunofluorescence analysis showed colocalization of these molecules in telophase (∼70% of cells; Figure 6H). Association of endogenous septin 2 and p85 was also shown by immunoprecipitation of septin 2 followed by Western blot (WB) detection p85 (Figure 7A, right panel). To characterize the p85 region that binds septin 2, we transfected cells with cDNA encoding different p85 mutants (Jiménez et al, 2000). Septin 2 associated with p50α (an alternatively spliced form encompassing the C-terminal SH2-SH2 region) and with p65PI3K, but not with the N-terminal SH3-Bcr p85 region (Figure 7A). We also found septin 2 association with Δp85 (not shown), which does not bind to p110 (Hara et al, 1994).

Figure 7.

p85 associates with septin 2. (A) We transfected NIH3T3 cells with cDNA encoding different p85 forms and confirmed transfection efficiency by WB (left). Extracts were immunoprecipitated (300 μg) with anti-septin 2 Ab and associated p85 examined in WB (right). (B) NIH3T3 cells were transfected with a control vector or cDNA encoding GFP-septin 2. Cell extracts (300 μg) were immunoprecipitated with anti-p85 or -GFP Ab (indicated). Immunoprecipitated proteins and extracts (40 μg) were resolved in SDS–PAGE and examined by WB with anti-p85 and -GFP Ab. (C, D) In vitro transcription and translation (using 35S-Met) reactions with indicated cDNA were examined by autoradiography. Reactions were also immunoprecipitated (IP) and examined by autoradiography. A longer exposure of the marked section (C, right) is included to visualize p85 in immunoprecipitates of GFP. Septin 2 was also identified in p85 immunoprecipitates by WB (D, right). Representative experiments of at least three performed, with similar results.

We studied septin 2/p85 association in a reverse analysis, by immunoprecipitating p85 and detecting septin 2 in WB. For this experiment, we transfected NIH3T3 cells with exogenous GFP-septin 2, as the IgG heavy chain masked WB detection of endogenous septin 2. We identified endogenous p85 associated with GFP-septin 2, as well as GFP-septin 2 in p85 immunoprecipitates (Figure 7B). Quantitation of the bands in this figure indicate that p85 brings down 50% the amount of GFP-Septin 2 detected in GFP immunoprecipitates, and approximately 15% of total GFP-Septin 2 input (examined in WB of total cell extracts). Detection of the complex by GFP immunoprecipitation was less efficient.

We also tested whether p85 associates directly with septin 2 in vitro, using translated GFP-septin 2 and p85α. p85 associated with GFP-septin 2, and GFP-septin 2 was identified in complex with p85 (Figure 7C); this complex was unaffected by the presence of p110α (not shown). As translation originates several synthesis intermediates, we confirmed by WB that GFP-septin 2 associates with p85α and p50α, but not with the SH3-Brc p85 region (Figure 7D). The amount of GFP-septin 2 bound to p85 immuno-complexes in vitro represented 20% of that present in immunoprecipitates using anti-GFP Ab. p85 thus associates with septin 2; association is direct but is higher within cells. Complex formation involves the N-SH2 and/or inter-SH2 domains of p85 and does not involve p110.

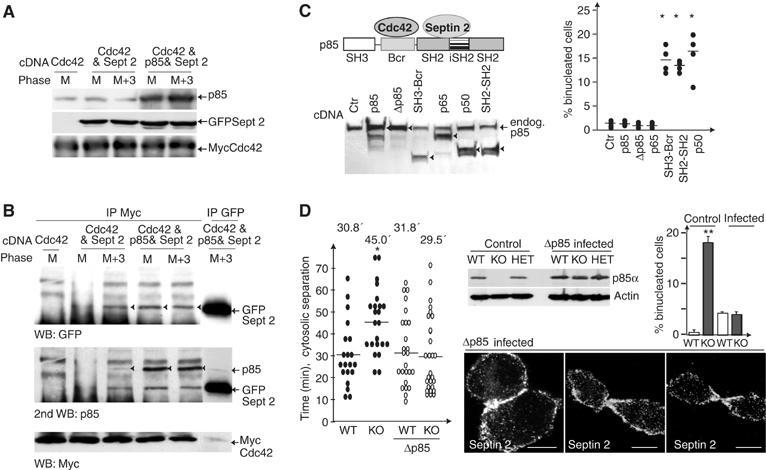

A Cdc42/p85/septin 2 complex regulates cytokinesis

As p85 associates with Cdc42 through the Bcr domain (Jiménez et al, 2000) and with septin 2 through the C-terminus, p85 could form a simultaneous complex with Cdc42 and septin 2. To examine triple-complex formation, we transfected Myc-tagged-Cdc42, as available anti-Cdc42 Ab are inefficient in WB; we also transfected GFP-septin 2, as the septin 2 Mr is similar to that of the IgG heavy chain. A ternary complex was not detected in exponentially growing cells (not shown). Although p85 binds septin 2 efficiently (Figure 7), the p85/Cdc42 association is inducible (Jiménez et al, 2000); we thus examined complex formation in mitosis, when p85, Cdc42-GTP and septin regulate cytokinesis. To enrich cultures in telophase cells, cells were synchronized in metaphase and released for 3 h. We verified transfected cDNA expression by WB (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

A ternary complex including Cdc42, p85, and septin 2 regulates cytokinesis. (A, B) NIH3T3 cells transfected with cDNA encoding p85, Myc-Cdc42 and GFP-septin 2 were arrested in metaphase (M), then released for 3 h (M+3). Transfection efficiency was tested in WB (A). Extracts (800 μg) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc or (400 μg) with anti-GFP Ab and examined in WB with anti-GFP (top) or -p85 Ab (middle). A fraction of the immunoprecipitates (10%) was examined in WB with anti-Myc Ab (bottom). (C) Squematic representation of p85 in complex with septin 2 and Cdc42. Expression of the different p85 forms transfected in NIH3T3 cells and percentage of binucleated cells in transfected cells. Each point represents an independent experiment. (D) WT, p85α+/− and p85α−/− MEF before and after Δp85α infection were examined by WB with anti-p85 Ab. Actin loading control is shown below. Time (min) required for cytosolic separation in Δp85α-expressing WT and p85α−/− MEF, compared to WT and p85α−/− MEF from Figure 1F. Percentage of binucleated cells in non-infected and infected (GFP+, ∼90%) cells. Septin 2 immunofluorescence analysis in Δp85α-reconstituted p85α−/− MEF (mitosis identified by DNA staining, not shown). Statistics were calculated as in Figure 1.

In these conditions, we detected GFP-septin 2 in Myc-Cdc42 immunoprecipitates, as well as Myc-Cdc42 in GFP-septin 2 immunoprecipitates (Figure 8B, top and bottom, respectively). Complexes involving endogenous p85 were larger in cultures enriched in telophases (Figure 8B, top). Transfection of exogenous p85 nonetheless enhanced complex formation, which was detected in metaphase and telophase (Figure 8B). p85 was associated to Cdc42 and to septin 2 (Figure 8B, middle). Quantitation of three experiments showed that the amount of GFP-septin 2 in complex with Cdc42 represented ∼9% of total input, and ∼20% the amount of GFP-septin 2 detected in immunoprecipitates using anti-GFP Ab. We barely detected triple complex formation in vitro (not shown); this could be due to a requirement for additional proteins or to a modification event in mitosis, as even in vivo, we detected the triple complex only in mitosis. This reflects that complex formation is induced in mitosis when Cdc42, p85, and septin 2 regulate cytokinesis.

To determine whether the Cdc42/p85/septin 2 complex has a function in control of cytokinesis, we interfered with endogenous complex formation by overexpressing recombinant p85 fragments that do not associate with septin 2 (SH3-Bcr domains) or Cdc42 (SH2-SH2 domains or p50α). Expression of SH3-Bcr or SH2-SH2 domains, or of p50α induced generation of binucleated cells (Figure 8C). In contrast, expression of p85α, Δp85 or p65PI3K, all of which associate with Cdc42 and septin 2, did not generate binucleated cells (Figure 8C). Transfection of these p85 constructs in HeLa cells also induced the appearance of binucleated cells (not shown). SH3-BcR or p50α expression impaired septin 2 localization in the cleavage furrow (not shown). These results indicate that the simultaneous association of p85 with Cdc42 and septin 2 is required for optimal cytokinesis.

Δp85 expression restores cytokinesis in p85α−/− cells

To demonstrate that defective cytokinesis in p85α−/− MEF is due primarily to p85α deletion, and not to PI3K activity defects, we reconstituted expression of a p85 regulatory subunit, using a p85α mutant that does not bind to p110 (Δp85α; Hara et al, 1994). Infection was >90% efficient, and Δp85α expression levels were similar to those of endogenous p85α (Figure 8D). Cells were examined by videomicroscopy; Supplementary video 7 shows a representative video (n=30) of Δp85α-reconstituted p85α−/− MEF. Consistent with the lack of p110 binding, Δp85α-reconstituted p85α−/− MEF cells still showed delayed metaphase plate formation (13.1±7.7 min) compared to WT cells (4.8±1.0). Metaphase was also delayed in control WT MEF expressing Δp85α, as approximately half of the total p85α (Δp85α) did not bind to p110 (12.6±6.3). DNA separation time was similar in WT, p85α−/− (see above), Δp85α-reconstituted WT (6.7±0.8 min), and Δ p85α-reconstituted p85α−/− MEF (6.5±1.1 min). Nevertheless, Δp85α expression significantly reduced the percentage of binucleated cells (Figure 8D). Moreover, mean cytokinesis progression time for Δp85α-expressing p85α−/− MEF (29.5±18.9 min) was similar to that of WT MEF (30.8±15.1 min) or Δp85α-expressing WT MEF (31.8±18.7 min). In addition, Δp85α expression corrected the phenotype defects in cytokinesis in p85α−/− MEF, including formation of long intracellular bridges and persistent filopodium formation (not shown). Finally, septin localization was similar in WT and Δp85α-reconstituted p85α−/− MEF (Figure 8D). These observations show that the cytokinesis defects in p85α−/− cells are caused primarily by the regulatory subunit deficiency, but also that cytokinesis is restored independently of PI3K activity.

Discussion

We studied the role of the PI3K regulatory subunit p85α in mitosis, and show that p85α deficiency induces cell accumulation in telophase, delayed cytokinesis, and appearance of binucleated cells. We show that one mechanism by which p85 regulates cytokinesis is by controlling local activation of Cdc42 and, in turn, septin 2 localization in the cleavage furrow. We base this proposal on the observation that p85α−/− cells had lower Cdc42-GTP levels that localized aberrantly during mitosis, and that interference with Cdc42 (and p85α deletion) induced septin 2 localization defects. Neither of these defects was induced by inhibition of PI3K activity. Moreover, cytokinesis defects in p85α−/− MEF were rescued by expression of the Δp85 mutant, which does not bind to p110. We found that p85α acts as a scaffold for Cdc42 and septin 2 binding, a mechanism by which p85 might regulate the septin cytoskeleton. Interference with Cdc42/p85/septin 2 complex formation impairs mammalian cytokinesis.

PI3K activation at mitosis entry was described in fibroblasts, MDCK and HeLa cells (Figure 2; Shtivelman et al, 2002; Dangi et al, 2003). Here, we confirm that PI3K inhibition in late S phase delayed mitosis entry (Shtivelman et al, 2002); nonetheless, we show that PI3K inhibition does not regulate cytokinesis (Figure 2). In contrast, it was proposed that PI3K activity controls cytokinesis in Dictyostelium discoideum, as PIP3 localizes to cell poles and PTEN to the cleavage furrow and simultaneous deletion of PI3K and PTEN inhibit cytokinesis (Janetopoulos et al, 2005). We found that PTEN localizes to the central spindle (not shown); thus, it is possible that the furrow localization is conserved in mammals. Nonetheless, neither activated PKB nor c-Rac was detected in telophase, arguing against a role for PI3K activity in mammalian cytokinesis (Yoshizaki et al, 2003; Oceguera-Yanez et al, 2005). Moreover, reconstitution of p85α−/− MEF with the Δp85 mutant (Hara et al, 1994) corrected the cytokinesis defects, showing that PI3K activity does not regulate this process.

We describe the contribution of the p85α regulatory subunit to cytokinesis, based on the longer p85α−/− MEF cytokinesis period, the accumulation of these cells in telophase, the large proportion of binucleated cells in cultures, and the appearance of telophase cells with long intracellular bridges. This p85 function in cytokinesis can operate only in vertebrates, as the invertebrate PI3K regulatory subunit does not have the SH3-Bcr region (i.e., Drosophila Acc No. Y12498). Expression of interfering p85 mutants also affected cytokinesis in NIH3T3 fibroblasts and HeLa cells. Moreover, various tissues in p85α−/− mouse embryos showed larger percentages of binucleated cells than WT embryos (Figure 1), supporting a general role for p85 in mammalian cytokinesis control.

Due to neonatal death of p85α−/− mice, the phenotype of these mice was previously studied by blastocyst complementation. This approach gives rise to chimeric mice in which only T and B cells are p85α−/−; the B cell differentiation defects observed were linked to reduced PI3K activity (Fruman et al, 1999). Binucleated cells in embryo sections might escape detection in a routine study, as the percentage of binucleated cells is small, although significant (mean 4.9%). Immunofluorescence staining of p85α-deficient MEF using anti-pan-p85 Ab showed p85β at the cleavage furrow (not shown). p85α and β may have a similar function in cytokinesis, although the p85β and p85α N-terminus are only partially conserved (∼60%). Definitive analysis awaits generation of an efficient anti-p85β Ab (in progress).

We propose that one mechanism by which p85α regulates cytokinesis is through reduction of local Cdc42 activation in the cleavage furrow. Defects in Cdc42 activity were quantitative, as seen in pull-down assays, and qualitative, as seen by time-lapse videomicroscopy. The videos showed that Cdc42-GTP localizes in the inner region of the cleavage furrow in WT MEF. Serial image analysis of WT cell videos suggested dynamic GTP-Cdc42 behavior during cytokinesis, as GTP-Cdc42 is seen alternately at the midzone MT region and the cytokinesis furrow. In p85α−/− MEF, Cdc42-GTP localized at the membrane, from which it eventually reached the cleavage furrow. The ectopic Cdc42-GTP localization in p85α−/− MEF correlates with prolonged filopodium formation, long intracellular bridges, delayed cytokinesis and failure of cytokinesis (∼20% of cells are binucleated). GTP-Cdc42 concentration at the furrow seems important for cytosolic division, as this event precedes cleavage furrow contraction in both WT and p85α−/− MEF.

In addition to controlling cytokinesis (Yasuda et al, 2004), Cdc42 is activated and localizes at the polar cell sides in prometaphase–metaphase (Yoshizaki et al, 2003; Oceguera-Yanez et al, 2005) and regulates MT chromosome attachment (Yasuda et al, 2004). Septin 2 also controls DNA separation (Spiliotis et al, 2005). DNA separation time was normal in p85α−/− cells, however, and only a small percentage of p85α−/− MEF showed unattached chromatids (∼7 versus ∼2% in WT MEF, P>0.05). The remaining Cdc42-GTP detected in metaphase in p85α−/− cells may be sufficient to trigger DNA separation, which is also regulated by other Rho-GTPases (Yasuda et al, 2004). Similarly, the defect in septin 2 localization is more frequent in telophase (>75% of cells) than metaphase (∼50%), suggesting that p85 primarily controls Cdc42 and septin 2 function in telophase.

p85 binds to Cdc42 through the Bcr region (Jiménez et al, 2000) and to septin 2 through the N-SH2 or inter-SH2 regions. We show that interference with ternary complex formation induced cytokinesis defects, indicating that the Cdc42/p85/septin 2 complex is required for optimal cytosolic division (Figure 8). Cdc42 governs septin ring formation and cytokinesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In this organism, septins regulate new membrane formation and fluidity, as well as cytosolic separation (Caviston et al, 2003; Kinoshita, 2003). Septins also control cytokinesis in mammals, as interference with septin 2 or the MSF septin inhibit cytokinesis (Kinoshita et al, 1997; Surka et al, 2002). The altered localization of septin 2 in telophase p85α−/− cells, driven by a defective Cdc42 regulation, provides a mechanism for the defective cytokinesis in p85α−/− cells.

The mechanism that controls the time and place of cytokinesis is the object of extensive research. In budding yeast, the mitosis exit network cascade regulates Cdk1 inactivation and cytokinesis. In fission yeast, the septation initiation network, activated following Cdk1 inhibition, initiates cytokinesis (Straight and Field, 2000). In mammals, the link between Cdk1 inactivation and furrow constriction is still poorly defined. Once Cdk1 activity is reduced, signals from central spindle MT dictate mitotic cleavage furrow formation (Straight and Field, 2000). A cascade has been proposed in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans that originates in MT and involves RhoA activation, which in turn induces actin polymerization at the cleavage furrow (Mishima et al, 2002; Somers and Saint 2003). There are mammalian homologs of this pathway. In fact, interference with RhoA activity induces appearance of binucleated cells in a proportion similar to that induced by p85α deletion (Yoshizaki et al, 2004). Our data show that, through Cdc42 regulation, p85 is involved in triggering septin 2 accumulation at the cleavage furrow. As p85 associates with MT (Kapeller et al, 1993), future studies will be oriented to determine whether Cdc42-GTP reaches the cleavage furrow through MT. p85/Cdc42 may represent a novel signal to dictate cleavage furrow formation by regulating the local concentration of septins. RhoA and Cdc42 could cooperate to trigger the cytoskeletal reorganization required for cell separation, as is the case for Xenopus wound healing (Benink and Bement, 2005).

Here we present a novel, PI3K activity-independent, function for the p85 regulatory subunit, which controls mammalian cytokinesis via regulation of Cdc42 and septin 2, both involved in the spatio-temporal control of cytosolic division.

Materials and methods

Cells and cDNA

MEF lines were prepared as described (Nagi et al, 2003), freshly isolated WT and p85α−/− lines were cultured and examined in parallel, and used during the first two weeks after preparation. NIH3T3 cells, ES cells, and MEF were cultured as described (Chen et al, 2000; Álvarez et al, 2001). pEXV-myc-WT-Cdc42, -N17-Cdc42, and all vectors encoding p85α and its mutant forms have been described (Jiménez et al, 2000), except for pSG5-SH2-SH2; in this construct the insert, starting at position 307 of murine p85α, was obtained by PCR and inserted into BamHI site of pSG5. To prepare pRV-myc-WT-Cdc42 IRES-Neo for MEF infection, myc-WT-Cdc42 was excised from pEXV-myc-WT-Cdc42 using BamHI and inserted into this site in pRV-IRES-Neo (Genetrix, Madrid, Spain). For intracellular localization studies, WT-Cdc42 (M57298) was obtained by PCR and subcloned into the XhoI and BamHI sites in pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). A mouse cDNA fragment encoding septin 2 (D49382) was cloned into the HindIII and AgeI sites of the pEGFP-C3 vector (Clontech). The CRIBPak1B domain was excised from pGex2T-CRIBPak1 using BamHI and EcoRI (Jiménez et al, 2000), and inserted into these sites in pcDNA3-CFP. HindIII- and EcoRI-restricted CFP-CRIBPak1B was subcloned into the same sites in the pLPC vector. pLPC-CFP-CRIBN-WASP was obtained by replacing CRIBPak1B with CRIBN-WASP in pLPC-CFP-CRIBPak1B, using BamHI and EcoRI sites. Gex2T-CRIBN-WASP was a gift from X Bustelo (CIC, Salamanca, Spain). To prepare pRV-IRES-Δp85α, Δp85α excised from SR-Δp85α (Hara et al, 1994) was subcloned into the pRV-IRES BamHI site.

Transfections, WB, pull-down, immunoprecipitation, infection and in vitro translation

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Gibco BRL), according to manufacturer's instructions. WB were as reported (Álvarez et al, 2001). Primary Ab for WB were anti-phospho-PKB (Cell Signaling), -PKB (Upstate Biotechnologies), -septin 2 (donated by I Macara; Joberty et al, 2001), -GFP (Roche Applied Science), -tubulin (Oncogene Research), -c-Myc (9E10; Jiménez et al, 2000 and C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), -β-actin (Sigma), -p85 (Upstate Biotechnologies), -p110α (a gift from A Klippel; Klippel et al, 1993) and -p110β Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Pull-down assays and retroviral infection were as described (Serrano et al, 1997; Jiménez et al, 2000).

To isolate the triple complex (Figure 8), we lysed cells in digitonin lysis buffer (1% digitonin, 10 mM triethanolamine, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM NaF, 2 mM PMSF, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin, pepstatin, and aprotinin, pH 8.0). Remaining lysates were prepared in TX-100 lysis buffer (Jiménez et al, 2000); immunoprecipitation was as reported (Jiménez et al, 2000). For immunoprecipitation, we used anti-p85β (N4; a gift from B Vanhaesebroeck; Reif et al, 1993), -septin 2 (donated by W Trimble, Surka et al, 2002), and -GFP Ab (Molecular Probes). In vitro transcription and translation was performed according to the instructions (Promega).

Cell cycle, immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Cell syncronization and arrest was previously described (Álvarez et al, 2001). For G0/G1 arrest, MEF were maintained in DMEM with 0.1% serum (3 days). DNA content, G2 arrest, and metaphase arrest (colcemid 100 ng/ml, 14 h) were measured as reported (Álvarez et al, 2001). In addition, we used a milder colcemid treatment (75 ng/ml, 12 h, yielding ∼60% cells with 4n DNA content) to accelerate metaphase re-establishment. Ly294002 (Calbiochem) was used at 10 μM. Mitotic cells were identified by simultaneous staining of DNA and actin or α-tubulin (Álvarez et al, 2001).

For immunofluorescence, more than 300 cells were examined under the microscope and 60-to-100 images were captured for each particular staining. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (7 min), in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (15 min) for MT staining, or in 4% formaldehyde with 2% sucrose (5 min) to examine GFP fusions. Permeabilization was in PBS with 1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100. Blocking, where needed, was performed using 1% BSA, 10% goat serum, 0.01% TX-100 (30 min). Cells were incubated with appropriate primary Ab (1 h, room temperature). Other antibodies for immunofluorescence were anti-α-tubulin (Oncogene), anti-γtubulin (Sigma), anti-Cdc42 (BD Biosciences and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, both gave similar results); septin 2 was stained using an antibody from I Macara and W Trimble (Joberty et al, 2001; Surka et al, 2002), which gave comparable results. Actin was stained with phalloidin-FITC or phalloidin-rhodamine (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cdc42, septin 2 and p85 Ab staining specificity was controlled by expression of GFP fusion proteins.

We used Cy3- and Cy2-conjugated goat anti-mouse and Cy3- and Alexa 488-goat anti-rabbit secondary Ab (Jackson Immunoresearch). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes) or DAPI (in mounting medium, Vector Laboratories). Cells were visualized using a × 63/1.4 aperture Plan Apo objective on an inverted microscope (Leica, Wetzlar Germany). Images, usually 512 × 512, were acquired using four-line mean averaging in a Z series typically containing four ∼2.5 μm sections for a total stack depth of ∼10 μm. Images were also acquired with an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope.

ES cells and whole embryo analysis

For immunofluorescence studies, ES cells were distinguished from feeder fibroblasts by assaying cytosolic alkaline phosphatase activity (developed with nitroblue tetrazolium; Sigma). Nuclei were identified with propidium iodide and RNAase. To analyze binucleated cells in vivo, 14.5 dpc mouse embryos were obtained, genotyped by PCR, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (overnight, 4°C); paraformaldehyde was eliminated in 30% sucrose (overnight, 4°C) and embryos were included in tissue freezing medium (Jung, Germany). Cryosections (10 μm) were stained with anti-pan-cadherin (Sigma) and Hoechst 33258, or with hematoxylin/eosin. Images were collected with a × 100 objective (pan-cadherin/Hoechst) or × 5 and × 40 objectives for tissue identification.

Phase contrast and CFP-CRIB time-lapse videomicroscopy

For phase contrast time-lapse microscopy, cells were seeded at 30% confluence; after 24 h, rounded cells with disaggregated nuclei were filmed. Images were captured using an Olympus CellR microscope every 45 s for 2.5 h. Images were processed using Olympus software, and videos mounted at 5 frames/s. Time intervals of mitotic processes were determined by counting film frames. Mitosis images of CFP-CRIBPak1-expressing cells were captured every 2–3 min on a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon C1). Images of CFP-CRIBN-WASP-expressing cells in mitosis were acquired every 60 s on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope. Images were processed using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the StatView 512+ program. Quantitation of gel bands and fluorescence intensity were performed using ImageJ software. For quantitation of septin 2 signal, after background correction, we integrated the total signal in the cleavage furrow membrane and in a similar area of the polar cell membrane, and then calculated the ratio. We also measured the mean signal intensity (per area unit) in the region of the cleavage furrow and the polar cell membrane.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary video 1

Supplementary video 2

Supplementary video 3

Supplementary video 4

Supplementary video 5

Supplementary video 6

Supplementary video 7

Legends to Supplementary Videos

Acknowledgments

We thank C Moreno and C Hernández for technical support, M Torres, S Mañes, and I Mérida for technical advice and C Mark for editorial assistance. We thank Drs R Tsien, I Macara, S Trimble, B Vanhaesebroeck, A Viola, X Bustelo, and A Klippel for reagents, and Dr D Fruman for p85α-deficient mice. ZG, MM, and IC received pre-doctoral fellowships from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science. This work was supported by grants from the European Union (QLRT2001-02171) and the Spanish DGCyDT (SAF2004.05955). The Department of Immunology and Oncology was founded and is supported by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and by Pfizer.

References

- Álvarez B, Martínez AC, Burgering BM, Carrera AC (2001) Forkhead transcription factors contribute to execution of the mitotic programme in mammals. Nature 413: 744–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benink HA, Bement WM (2005) Concentric zones of active RhoA and Cdc42 around single cell wounds. J Cell Biol 168: 429–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviston JP, Longtine M, Pringle JR, Bi E (2003) The role of Cdc42p GTPase-activating proteins in assembly of the septin ring in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 14: 4051–4066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Ma L, Parrini MC, Mao X, Lopez M, Wu C, Marks PW, Davidson L, Kwiatkowski DJ, Kirchhausen T, Orkin SH, Rosen FS, Mayer BJ, Kirschner MW, Alt FW (2000) Cdc42 is required for PIP(2)-induced actin polymerization and early development but not for cell viability. Curr Biol 10: 758–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangi S, Cha H, Shapiro P (2003) Requirement for PI3K activity during progression through S-phase and entry into mitosis. Cell Signal 15: 667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JW, Zhang C, Kahn RA, Evans T, Cerione RA (1996) Mammalian Cdc42 is a brefeldin A-sensitive component of the Golgi apparatus. J Biol Chem 271: 26850–26854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA, Snapper SB, Yballe CM, Davidson L, Yu JY, Alt FW, Cantley LC (1999) Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of PI3K p85alpha. Science 283: 393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Yonezawa K, Sakaue H, Ando A, Kotani K, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Ueda H, Stephens L, Jackson TR, Hawkins PT, Dhand R, Clark AE, Holdman GD, Waterfield MD, Kasuga M (1994) PI3K activity is required for insulin-stimulated glucose transport but not for RAS activation in CHO cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 7415–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janetopoulos C, Borleis J, Vazquez F, Iijima M, Devreotes P (2005) Temporal and spatial regulation of phosphoinositide signaling mediates cytokinesis. Dev Cell 8: 467–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez C, Portela RA, Mellado M, R-Frade JM, Collard J, Serrano A, Martínez AC, Avila J, Carrera AC (2000) Role of the PI3K regulatory subunit in the control of actin organization and cell migration. J Cell Biol 151: 249–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joberty FG, Perlungher RR, Sheffield PJ, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Haystead T, Macara IG (2001) Borg proteins control septin organization and are negatively regulated by Cdc42. Nat Cell Biol 3: 861–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapeller R, Chakrabarti R, Cantley L, Fay F, Corvera S (1993) Internalization of activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor–PI3K complexes: potential interactions with the microtubule cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol 13: 6052–6063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M (2003) The septins. Genome Biol 4: 236–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Kumar S, Mizoguchi A, Ide C, Kinoshita A, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y, Noda M (1997) Nedd5, a mammalian septin, is a novel cytoskeletal component interacting with actin-based structures. Genes Dev 11: 1535–1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel A, Escobedo JA, Hu Q, Williams LT (1993) A region of the 85-kilodalton (kDa) subunit of PI3K binds the 110-kDa catalytic subunit in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 13: 5560–5566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kamijo K, Ohara N, Kitamura T, Miki T (2004) MgcRacGAP regulates cortical activity through RhoA during cytokinesis. Exp Cell Res 293: 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gac L, Marques M, Garcia Z, Campanero MR, Carrera AC (2004) Control of cyclin G2 mRNA expression by forkhead transcription factors: novel mechanism for cell cycle control by PI3K and forkhead. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2181–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki H, Sasaki T, Takai Y, Takenawa T (1998) Induction of filopodium formation by a WASP-related actin-depolymerizing protein N-WASP. Nature 391: 93–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Kaitna S, Glotzer M (2002) Central spindle assembly and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity. Dev Cell 2: 41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi A, Gertsenstein K, Vintersten K, Behringer RR (2003) Manipulating the Mouse Embryo: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd edn, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Oceguera-Yanez F, Kimura K, Yasuda S, Higashida C, Kitamura T, Hiraoka Y, Haraguchi T, Narumiya S (2005) Ect2 and MgcRacGAP regulate the activation and function of Cdc42 in mitosis. J Cell Biol 168: 221–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prothero JW, Spencer D (1968) A model of blebbing in mitotic tissue culture cells. Biophys J 9: 41–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif K, Gout I, Waterfield MD, Cantrell DA (1993) Divergent regulation of PI3K p85 alpha and p85 beta isoforms upon T cell activation. J Biol Chem 268: 10780–10788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW (1997) Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88: 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtivelman E, Sussman J, Stokoe D (2002) A role for PI 3-kinase and PKB activity in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. Curr Biol 12: 919–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers WG, Saint R (2003) A RhoGEF and Rho family GTPase-activating protein complex links the contractile ring to cortical microtubules at the onset of cytokinesis. Dev Cell 4: 29–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiliotis ET, Kinoshita M, Nelson WJ (2005) A mitotic septin scaffold required for Mammalian chromosome congression and segregation. Science 307: 1781–1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Field CM (2000) Microtubules, membranes and cytokinesis. Curr Biol 10: 760–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surka MC, Tsang CW, Trimble WS (2002) The mammalian septin MSF localizes with microtubules and is required for completion of cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3532–3545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki K, Fruman DA, Yballe CM, Fasshauer M, Klein J, Asano T, Cantley LC, Kahn CR (2003) Positive and negative roles of p85 alpha and p85 beta regulatory subunits of PI3K in insulin signaling. J Biol Chem 278: 48453–48466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki K, Yballe CM, Brachmann SM, Vicent D, Watt JM, Kahn CR, Cantley LC (2002) Increased insulin sensitivity in mice lacking p85beta subunit of PI3K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 419–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD (1999) Signaling by distinct classes of PI3K. Exp Cell Res 253: 239–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Oceguera-Yanez F, Kato T, Okamoto M, Yonemura S, Terada Y, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S (2004) Cdc42 and mDia3 regulate microtubule attachment to kinetocores. Nature 428: 767–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki H, Ohba Y, Kurokawa K, Itoh RE, Nakamura T, Mochizuki N, Nagashima K, Matsuda M (2003) Activity of Rho-family GTPases during cell division as visualized with FRET-based probes. J Cell Biol 162: 223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki H, Ohba Y, Parrini MC, Dulyaninova NG, Bresnick AR, Mochizuki N, Matsuda M (2004) Cell type specific regulation of Rho A activity during cytokinesis. J Biol Chem 279: 44756–44762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary video 1

Supplementary video 2

Supplementary video 3

Supplementary video 4

Supplementary video 5

Supplementary video 6

Supplementary video 7

Legends to Supplementary Videos