Abstract

Mitofusins and Drp1 are key components in mitochondrial membrane fusion and division, but the molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of their activities remains to be clarified. Here, we identified human membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH)-V as a novel transmembrane protein of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that MARCH-V interacts with mitofusin 2 (MFN2) and ubiquitinated forms of Drp1. Overexpression of MARCH-V promoted the formation of long tubular mitochondria in a manner that depends on MFN2 activity. By contrast, mutations in the RING finger caused fragmentation of mitochondria. We also show that MARCH-V promotes ubiquitination of Drp1. These results indicate that MARCH-V has a crucial role in the control of mitochondrial morphology by regulating MFN2 and Drp1 activities.

Keywords: membrane-associated RING-CH, mitofusin, mitochondria, RING finger, ubiquitin

Introduction

Mitochondria frequently fuse and divide to form a dynamic network in various eukaryotic cells (Nunnari et al, 1997; Yaffe, 1999). In mammals, the key molecules for mitochondrial dynamics are mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1 and MFN2), which are involved in fusion, and Drp1, which is involved in division. Mitofusins are large transmembrane GTPases of the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) and cooperate to fuse the mitochondrial membrane in a GTPase-dependent manner (Santel & Fuller, 2001; Rojo et al, 2002; Chen et al, 2003; Eura et al, 2003; Santel et al, 2003; Ishihara et al, 2004). Drp1 is a cytosolic dynamin-related GTPase and assembles on the MOM at sites of division (Smirnova et al, 1998, 2001). A loss of mitofusin function causes mitochondrial fragmentation (Chen et al, 2003; Eura et al, 2003; Santel et al, 2003; Honda et al, 2005). By contrast, inhibition of Drp1 function results in long tubular mitochondria (Smirnova et al, 1998, 2001; Frank et al, 2001; Lee et al, 2004). Although these factors are of fundamental importance in maintaining morphological and functional integrities of mitochondria, the precise mechanisms underlying the regulation of their activities remain poorly understood.

Here, we identified a novel ubiquitin ligase of the MOM. The protein is membrane-associated RING-CH (MARCH)-V, a member of the transmembrane RING-finger protein family the biological functions of which are only beginning to emerge (Lehner et al, 2005). We show that MARCH-V has the ability to bind to MFN2 and Drp1, to ubiquitinate Drp1 and to modify mitochondrial morphology, which provides evidence for a novel regulatory mechanism for mitochondrial dynamics.

Results

MARCH-V is a novel mitochondrial ubiquitin ligase

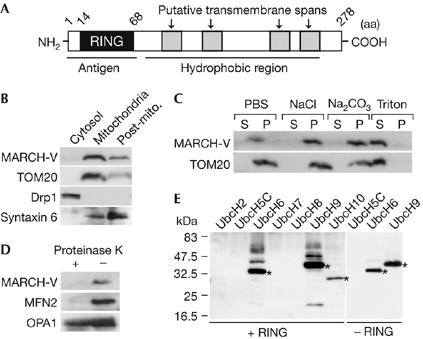

The sequence of human MARCH-V was found by Blast searches using the sequence of MARCH-II, which we previously identified (Nakamura et al, 2005), as the query. MARCH-V consists of 278 amino-acid residues with an amino-terminal RING finger and four carboxy-terminal transmembrane spans (Fig 1A). The recent proteomics analysis of mitochondria in the human heart identified MARCH-V (Taylor et al, 2003). Consistent with this, endogenous MARCH-V was detected in the mitochondrial fraction of COS7 cells by western blotting (Fig 1B). MARCH-V could be extracted from membranes with Triton X-100, but not with high-salt buffer or alkaline solution, indicating that it is an integral membrane protein (Fig 1C). When intact mitochondria were treated with proteinase K, MARCH-V and the MOM protein MFN2 were digested, whereas the intermembrane space protein OPA1 was protected (Fig 1D), suggesting that MARCH-V is localized to the MOM. An in vitro ubiquitination assay showed that recombinant proteins of the MARCH-V RING finger catalysed the formation of polyubiquitinated products in the presence of the E2 enzymes UbcH6 or UbcH9 (Fig 1E). Together, these results indicate that MARCH-V is a transmembrane E3 ubiquitin ligase of the MOM.

Figure 1.

Characterization of MARCH-V. (A) Schematic drawing of the potential structure of MARCH-V. (B) The cytosol, mitochondria and post-mitochondria (Post-mito.) fractions (15 μg of protein) of COS7 cells were analysed by western blotting with antibodies to MARCH-V, TOM20, Drp1 and syntaxin 6 (a Golgi/endosomal protein). (C) The total membrane fractions of COS7 cells were incubated with PBS, 1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11) or 1% Triton X-100 for 1 h on ice. After ultracentrifugation, the supernatant (S) and pellets (P; 20 μg of protein each) were analysed by western blotting. (D) The mitochondrial fractions were incubated with (+) or without (−) 100 μg/ml proteinase K for 1 h on ice. After quenching proteolysis by addition of phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (1 mM final), the mitochondria were pelleted, dissolved in SDS sample buffer and analysed by western blotting. (E) Reaction mixtures containing E1, E2 indicated above the lanes and ubiquitin (Ub) were incubated in the presence (+RING) or absence (−RING) of glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins of the MARCH-V RING finger for 2 h at 30°C. Ubiquitinated materials were detected by western blotting with anti-Ub antibody. Asterisks indicate Ub-charged E2s.

Expression of MARCH-V affects mitochondrial morphology

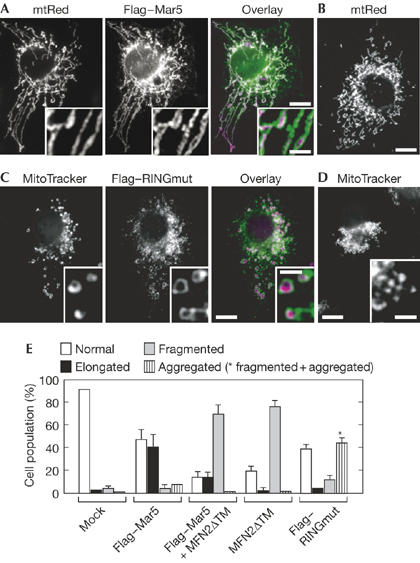

When a 3 × Flag-tagged MARCH-V construct (Flag–Mar5) was transiently transfected into COS7 cells stably expressing matrix-targeted red fluorescent protein (mtRed; COSmtRed cells), Flag–Mar5 was localized to mitochondria surrounding mtRed, supporting the MOM localization of MARCH-V (Fig 2A). Interestingly, around 40% of the transfected cells showed aberrant mitochondrial morphology that was much longer than mitochondria of non- and mock-transfected cells (Fig 2A compared with Fig 2B,E). This mitochondrial elongation was prevented by coexpression of an MFN2 mutant lacking the transmembrane spans (MFN2ΔTM), which has a dominant-negative effect on mitochondrial fusion (Honda et al, 2005), and 70% of the co-transfected cells showed extensive mitochondrial fragmentation without affecting the MOM localization of Flag–Mar5 (Fig 2E; supplementary Fig 1A online). Furthermore, around 55% of cells overexpressing the mutant MARCH-V (Flag–RINGmut) containing point mutations at conserved His 43, Cys 46 and Trp 50 residues of the RING finger, which are crucial for ubiquitin ligase activity, showed mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig 2C,E). The punctate mitochondria accumulated mostly (44%) in the perinuclear region (Fig 2D,E). These results indicate that MARCH-V overexpression promotes the formation of elongated mitochondria, which is dependent on its RING finger and on the activity of MFN2.

Figure 2.

Effects of MARCH-V overexpression on mitochondrial morphology. (A,B) COS7 cells stably expressing matrix-targeted red fluorescent protein (mtRed) were transiently transfected with Flag–Mar5 and stained with Flag antibody. Signals for Flag and mtRed are shown in green and magenta, respectively. Insets show higher magnification images. A typical example of normal mitochondrial morphology in non-transfected cells is shown in (B). Scale bars, 10 (A,B) and 2 μm (A, inset). (C,D) COS7 cells transiently transfected with Flag–RINGmut were stained with Flag antibody and MitoTracker. Signals for Flag and MitoTracker are shown in green and magenta, respectively. Insets show higher magnification images. Expression of Flag–RINGmut caused aggregation of fragmented mitochondria in the perinuclear region, as shown in (D). Scale bars, 10 and 2 μm (insets). (E) Percentage of cell population with normal (open bar), elongated (solid bar), fragmented (grey bar) and aggregated (striped bar) mitochondria in COS7 cells transiently transfected with mock (n=527), Flag–Mar5 (n=306), Flag–Mar5 plus MFN2ΔTM (n=302), MFN2ΔTM (n=303) or Flag–RINGmut (n=306). The asterisk represents the cell population of aggregated and fragmented mitochondria. Data represent the mean±s.d. of three independent experiments.

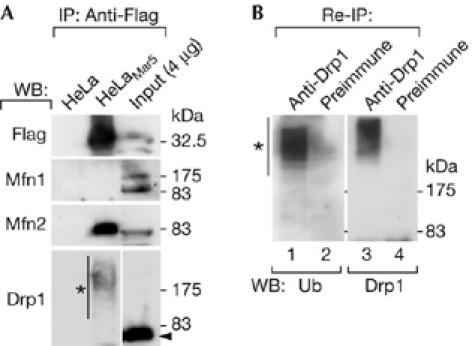

MARCH-V binds to mitofusin 2 and Drp1

The above findings led us to examine the possibility that MARCH-V interacts with mitofusins and Drp1. Lysates of HeLa cells stably expressing Flag–Mar5 (HeLaMar5 cells) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag beads. Western blotting of the immunoprecipitates showed that endogenous MFN2, but not MFN1, was co-precipitated with Flag–Mar5 (Fig 3A). Interestingly, a high-molecular-weight smear of Drp1 was detected above its molecular weight of 82 kDa (Fig 3A, asterisk). When the high-molecular-weight forms of Drp1 were subjected to a second immunoprecipitation with Drp1 antiserum followed by western blotting with ubiquitin antibody, the smear signal was detected again (Fig 3B), indicating that the upward shift of Drp1 was due to ubiquitination. We also detected the interaction of endogenous MARCH-V with MFN2 and ubiquitinated Drp1 (supplementary Fig 2 online).

Figure 3.

Association of MARCH-V with mitofusin 2 and ubiquitinated Drp1. (A) Total cell lysates of HeLa or HeLaMar5 cells were incubated with anti-Flag beads followed by western blotting (WB). The lysate of HeLaMar5 cells (0.4% of the input) was run in parallel. The arrowhead and the asterisk indicate the positions of unmodified and modified Drp1, respectively. IP, immunoprecipitation. (B) The anti-Flag immunoprecipitants of HeLaMar5 cells were further immunoprecipitated with either rabbit Drp1 antiserum (lanes 1,3) or preimmune serum (lanes 2,4) followed by western blotting with a monoclonal antibody to ubiquitin (Ub; lanes 1,2) or Drp1 (lanes 3,4). The asterisk indicates ubiquitinated Drp1. HeLaMar5, HeLa cells stably expressing Flag–Mar5.

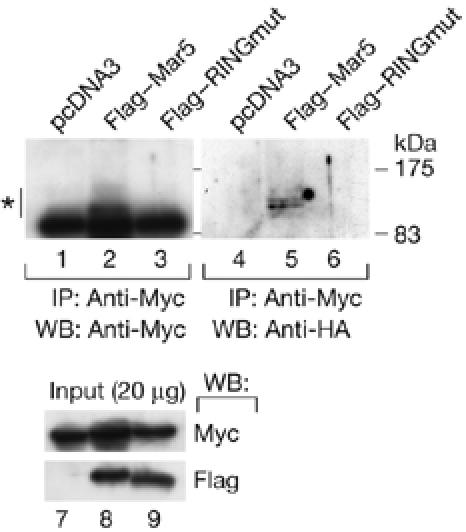

MARCH-V targets Drp1 for ubiquitination

To determine whether MARCH-V acts as a ubiquitin ligase to ubiquitinate Drp1, 6 × Myc-tagged Drp1 was coexpressed in COS7 cells with haemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ubiquitin in the absence or presence of Flag–Mar5 or Flag–RINGmut. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Myc antibody followed by western blotting with anti-HA antibody to detect ubiquitinated Drp1. As shown in Fig 4, increased levels of HA–ubiquitin were detected on 6 × Myc–Drp1 only in the presence of Flag–Mar5, indicating that MARCH-V promotes ubiquitination of Drp1.

Figure 4.

Ubiquitination of Drp1 by MARCH-V. COS7 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids encoding HA–ubiquitin (0.6 μg), 6 × Myc–Drp1 (1.0 μg) and empty vector (lanes 1,4,7), Flag–Mar5 (lanes 2,5,8) or Flag–RINGmut (lanes 3,6,9; 1.4 μg). Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc beads followed by western blotting (WB) with Myc (top left) or HA antibody (top right). The asterisk indicates ubiquitinated Drp1. The bottom panel shows the result of western blotting of the lysates with Myc or Flag antibody. HA, haemagglutinin.

Discussion

In this study, we identified MARCH-V as a novel component of mitochondria that interacts with MFN2 and Drp1. A notable finding is that overexpression of MARCH-V resulted in a change in mitochondrial shape to elongated tubular structures. Morphology and distribution of mitochondria are maintained by a balance between mitochondrial fusion and division (Nunnari et al, 1997; Yaffe, 1999). The mitochondrial elongation by MARCH-V could be due to an increase in mitochondrial fusion, a decrease in division or a combination of both. Because MFN2ΔTM induced mitochondrial fragmentation even under MARCH-V overexpression, it is conceivable that MARCH-V does not have the intrinsic ability to fuse mitochondria and that its effect is exerted through MFN2 activity. Under physiological conditions, MARCH-V might control mitochondrial fusion by modulating MFN2 activity through physical association. From a recent report that mitochondrial fusion is promoted by activation of MFN2 GTPase activity (Neuspiel et al, 2005), it is evident that elevated MARCH-V levels possibly resulted in an increase in its interaction with MFN2, leading to activation of MFN2 at levels sufficient to promote mitochondrial fusion. Moreover, a mutational study showed that mitochondrial elongation by MARCH-V requires an intact RING finger and that Flag–RINGmut led to mitochondrial fragmentation, suggesting that ubiquitin activity is involved in the effect on mitochondrial morphology. In addition, MARCH-V acts as a ubiquitin ligase for Drp1 and forms a complex only with ubiquitinated forms of Drp1 at steady state. These findings raise the possibility that an increase in Drp1 ubiquitination could have an inhibitory effect on mitochondrial division, similar to GTPase-deficient mutants of Drp1 (Smirnova et al, 1998, 2001; Frank et al, 2001), in turn stimulating mitochondrial elongation to some extent. Recently, SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) modification was shown to protect Drp1 from degradation at sites where mitochondrial division occurs (Harder et al, 2004). Thus, our data suggest that mitochondrial division is regulated by two distinct mechanisms: SUMOylation and ubiquitination. Given that these modifications cause different effects on some cellular processes (Gill, 2004), ubiquitin modification might negatively regulate the activity and/or stability of Drp1. Several genetic studies in yeast have suggested that ubiquitin ligases are required for maintenance of mitochondrial morphology, including Rsp5 (Fisk & Yaffe, 1999) and the Skp1/Cullin/F-box protein (SCF) complex (Fritz et al, 2003; Altmann & Westermann, 2005). Our finding also provides further evidence of the involvement of the ubiquitin system in mammalian mitochondrial dynamics.

Database searches showed that no orthologous MARCH-V gene exists in Caenorhabditis elegans or yeast, suggesting that higher eukaryotes have evolved regulatory mechanisms for mitochondrial functions. On the basis of the action and ubiquitous expression of MARCH-V (supplementary Fig 3 online), it might have an essential role in the control of mitochondrial dynamics as a dual modulator of MFN2 and Drp1.

Methods

The methods used are described in the supplementary information online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

supplementary Fig 1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (14104002) and the 21st Century COE Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- Altmann K, Westermann B (2005) Role of essential genes in mitochondrial morphogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 16: 5410–5417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Detmer SA, Ewald AJ, Griffin EE, Fraser SE, Chan DC (2003) Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol 160: 189–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eura Y, Ishihara N, Yokota S, Mihara K (2003) Two mitofusin proteins, mammalian homologues of FZO, with distinct functions are both required for mitochondrial fusion. J Biochem (Tokyo) 134: 333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk HA, Yaffe MP (1999) A role for ubiquitination in mitochondrial inheritance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 145: 1199–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ (2001) The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell 1: 515–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz S, Weinbach N, Westermann B (2003) Mdm30 is an F-box protein required for maintenance of fusion-competent mitochondria in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 14: 2303–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G (2004) SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev 18: 2046–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder Z, Zunino R, McBride H (2004) Sumo1 conjugates mitochondrial substrates and participates in mitochondrial fission. Curr Biol 14: 340–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S, Aihara T, Hontani M, Okubo K, Hirose S (2005) Mutational analysis of action of mitochondrial fusion factor mitofusin-2. J Cell Sci 118: 3153–3161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Eura Y, Mihara K (2004) Mitofusin 1 and 2 play distinct roles in mitochondrial fusion reactions via GTPase activity. J Cell Sci 117: 6535–6546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Jeong SY, Karbowski M, Smith CL, Youle RJ (2004) Roles of the mammalian mitochondrial fission and fusion mediators Fis1, Drp1, and Opa1 in apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell 15: 5001–5011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner PJ, Hoer S, Dodd R, Duncan LM (2005) Downregulation of cell surface receptors by the K3 family of viral and cellular ubiquitin E3 ligases. Immunol Rev 207: 112–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N, Fukuda H, Kato A, Hirose S (2005) MARCH-II is a syntaxin-6-binding protein involved in endosomal trafficking. Mol Biol Cell 16: 1696–1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuspiel M, Zunino R, Gangaraju S, Rippstein P, McBride H (2005) Activated mitofusin 2 signals mitochondrial fusion, interferes with Bax activation, and reduces susceptibility to radical induced depolarization. J Biol Chem 280: 25060–25070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari J, Marshall W, Straight A, Murray A, Sedat J, Walter P (1997) Mitochondrial transmission during mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is determined by mitochondrial fusion and fission and the intramitochondrial segregation of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biol Cell 8: 1233–1242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojo M, Legros F, Chateau D, Lombès A (2002) Membrane topology and mitochondrial targeting of mitofusins, ubiquitous mammalian homologs of the transmembrane GTPase Fzo. J Cell Sci 115: 1663–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santel A, Fuller MT (2001) Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J Cell Sci 114: 867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santel A, Frank S, Gaume B, Herrler M, Youle R, Fuller MT (2003) Mitofusin-1 protein is a generally expressed mediator of mitochondrial fusion in mammalian cells. J Cell Sci 116: 2763–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova E, Shurland DL, Ryazantsev SN, van der Bliek AM (1998) A human dynamin-related protein controls the distribution of mitochondria. J Cell Biol 143: 351–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova E, Griparic L, Shurland DL, van der Bliek AM (2001) Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 12: 2245–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SW et al. (2003) Characterization of the human heart mitochondrial proteome. Nat Biotechnol 21: 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MP (1999) The machinery of mitochondrial inheritance and behavior. Science 283: 1493–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplementary Fig 1