Short abstract

Most child deaths in the region are preventable and occur in just a few of the 22 countries in the region. The interventions are not expensive, but governments need to implement them

Over 10 million children aged under 5 years die every year, almost 90% of them in a few countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.1-6 Landmark series on child and neonatal survival suggested that this high mortality persists despite low cost solutions being known and that almost 60-70% of these deaths could be prevented by making these interventions widely available.2,4 To evaluate whether countries have acted on this information, we did an in-depth assessment of child health in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean region. The region comprises 22 predominantly Islamic countries, and health indicators vary widely.

Review methods

We used data from WHO and Unicef to determine child deaths and cause specific mortality.7,8 We obtained information from the official websites of ministries of health and nationally accredited institutions or research organisations, describing national research priorities for child health, funding for research, and policy. In addition, we reviewed research funding data from the WHO (Eastern Mediterranean Region) research cooperation and policy unit on subjects directly or indirectly related to newborn and child health as well as information available on activities within the region from other United Nations agencies (Unicef, UN Population Fund, UN Development Programme), World Bank, and major bilateral donors. We also evaluated the evidence base for established interventions as well as relatively new strategies for addressing newborn and child health in health system settings. Finally, we assessed the relation between government effectiveness and child health. Full details of the methods are on bmj.com.

Child mortality in the region

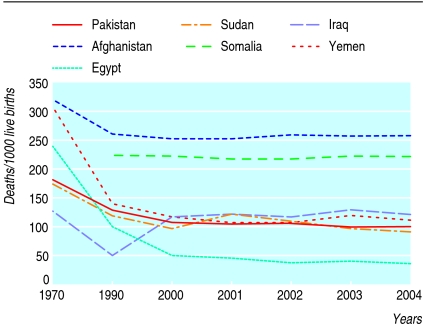

The Eastern Mediterranean region accounts for almost 15% of the total global burden of newborn and child mortality, most of which is concentrated in a few countries. Of the current 1.4 million deaths among children under 5 in the region every year, over 1.2 million (91%) occur in just seven countries (Pakistan, Afghanistan, Egypt, Sudan, Somalia, Iraq, and Yemen) with mortality exceeding 50/1000 live births. Despite falls in mortality from 1970 to 1990, rates in these countries have recently increased (Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia) or stagnated (figure). Accurate data for child health indicators in the Gaza Strip and Darfur are not available, and we do not yet know the full effect of the current humanitarian crisis in Lebanon on child health.

Figure 1.

How many lives can we save and how?

Table 1 indicates the distribution of child deaths from specific causes and the proportions that are preventable in the seven high burden countries of the region. Table 2 details various intervention strategies and their effect on child mortality. We assumed a target of 90% coverage except for the expanded programme of immunisation and tetanus toxoid, for which we assumed 95% coverage. Although these targets are lower than the assumed 99% coverage in the child survival series,2 our analysis indicates that these interventions can still potentially save 52% of all newborn and child deaths in these countries. If we could add newer interventions, including the vaccines for rotavirus diarrhoea and invasive pneumococcal disease, as well as other strategies for secondary care of preterm infants,9 an additional 10-15 % lives can be saved.

Table 1.

Total and preventable deaths in children aged under 5 years in Eastern Mediterranean countries with mortality above 50/1000 live births

| Disease or condition | No of deaths in 2004 (000s) | No (%) preventable (000s) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-neonatal: | ||

| Diarrhoea | 238 | 180 (75.6) |

| Pneumonia | 291 | 178 (61.2) |

| Measles | 56 | 42 (74.6) |

| Malaria | 37 | 32 (84.3) |

| HIV and AIDS | 4 | 3 (68.1) |

| Other | 186 | 0 |

| Neonatal: | ||

| Asphyxia | 117 | 58 (49.1) |

| Prematurity | 127 | 63 (49.6) |

| Sepsis/pneumonia | 167 | 100 (59.9) |

| Tetanus | 69 | 44 (64.1) |

| Diarrhoea | 21 | 3 (15.9) |

| Congenital disorders | 52 | 2 (4.2) |

| Other | 33 | 1 (2.1) |

| Total | 1401 | 706 (50.4) |

Numbers do not always calculate exactly because of rounding.

Table 2.

Estimate of deaths averted (in thousands) among children aged under 5 years by interventions in Eastern Mediterranean countries with mortality above 50/1000 live births

| Intervention | No (%) of deaths prevented |

|---|---|

| Preventive | |

| Family and community care: | |

| Periconceptual folic acid | 4 (0.3) |

| Promotion of breast feeding | 151 (10.8) |

| Appropriate complementary feeding strategies including dietary diversification | 54 (3.9) |

| Water, sanitation, and hygiene strategies | 31 (2.2) |

| Outreach services: | |

| Effective antenatal care | 17 (1.2) |

| Tetanus toxoid administration | 36 (2.6) |

| Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy | 2 (0.2) |

| Insecticide treated materials for malaria | 24 (1.7) |

| Vitamin A supplementation | 11 (0.8) |

| Clinic based care: | |

| Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy | 8 (0.6) |

| Skilled maternal and immediate newborn care | 53 (3.8) |

| Antenatal steroids in high risk cases (preterm births) | 23 (1.6) |

| Extra care of low birthweight infants | 19 (1.4) |

| Haemophillus influenzae B vaccine (as part of standard vaccination schedule) | 29 (2.1) |

| Measles vaccine | 30 (2.1) |

| Treatment | |

| Family and community care: | |

| Oral rehydration therapy | 65 (4.7) |

| Appropriate antibiotics for pneumonia | 42 (3.0) |

| Outreach services: | |

| Zinc for diarrhoea | 4 (0.3) |

| Appropriate antimalarials including artemisin combination | 4 (0.3) |

| Clinic based care: | |

| Antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes | 5 (0.3) |

| Emergency obstetric care | 19 (1.3) |

| Emergency newborn care | 35 (2.5) |

| Appropriate treatment of neonatal pneumonia | 31 (2.2) |

| Antibiotics for dysentery | 6 (0.4) |

| Vitamin A for measles | 1 (0.1) |

| Antiretroviral treatment | 3 (0.2) |

So why are these interventions not happening? The explanations relate to issues such as lack of awareness at the policy level of the importance of child survival, the specific packages of interventions selected by programmes, and efforts to scale up delivery strategies in health systems. We found a close correlation between our index of government effectiveness—that is, ability to implement policy—and child mortality (see fig B on bmj.com). Although specific data on national spending for newborn and child health in the high burden countries were not available, overall funding levels for health services varied considerably. Figure B on bmj.com indicates the relation of the health to defence expenditure ratio and infant mortality in Eastern Mediterranean countries with the highest numbers of child deaths

Scaling up delivery is recognised as essential to meeting the millennium development goals10 and must be supported with financial and other resources. Current coverage for many of these interventions is extremely variable, with big contrasts between rural and urban populations for some basic newborn and child survival interventions such as skilled care at birth, measles vaccination, and nutrition support programmes tackling chronic under-nutrition problems such as stunting (see fig D on bmj.com).

The state of maternal care and strategies for newborn care in these countries clearly contribute to the persistently high rates of newborn deaths. A large proportion of all births take place at home with unskilled attendants, and few community based strategies or outreach programmes for maternal and newborn care are in place. Despite the success of composite community based initiatives,11 only Pakistan and Iran have been able to set up a robust programme of interventions through community based health workers.12,13 Although much of the focus has been on community delivery of specific interventions and commodities, the effect of such programmes can be greatly increased by strategies aimed at empowerment of women, domiciliary practices, community engagement, and governance of services.

Over the past few years, the evidence on the feasibility and potential impact of community based interventions and innovative delivery strategies has greatly improved.13-15 Many of the interventions to prevent child deaths that our analysis identified could be delivered to whole populations through community based approaches and outreach programmes. However, efforts for implementing and scaling up these interventions are slow in most countries. More importantly, where interventions exist, monitoring and evaluation frameworks are poor and effectiveness evaluation and research extremely limited.

Importance of research into effectiveness

Evaluation of the effectiveness of child survival interventions is critical to generating the momentum to introduce and increase their coverage within health systems.16 Evaluation does not always require randomised controlled trials. Alternative study methods, such as well designed observational studies or phased introduction of interventions through a step-wedge design can also provide strong evidence to inform policy making for child health.17 Little research has been done on the effectiveness of essential child health interventions and delivery packages,18 particularly community based interventions and outreach programmes. Such evidence and experience in real health systems is critical in developing policy, particularly for newer interventions such as use of zinc for diarrhoea. This was highlighted by the recent evaluation of supervised and unsupervised treatment of children with malaria in Myanmar, which showed that an inexpensive dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine combination was as effective as artesunate-mefloquine.19

Summary points

Child deaths in the Eastern Mediterranean region account for 15% of the total global burden for newborn and child mortality

Most of the deaths occur in just seven countries, several of which are in a state of conflict

Available evidence based interventions, if fully implemented, can prevent half of all child deaths in these countries

Barriers to implementation of these interventions are not so much lack of knowledge as political will and appropriate allocation of resources

We also evaluated the evidence base and gaps for many of the interventions when packaged together according to current delivery strategies. As table B on bmj.com shows, much of the evidence has been derived from relatively small scale efficacy studies, and few interventions have been evaluated in whole health systems. Very few research projects are evaluating strategies for scaling up child survival interventions to whole health systems (total expenditure under $4m (£2m, €3m)). We could identify only three projects during 2000-4 in the region that had evaluated the effectiveness of country-wide child survival interventions or packages.

Role of social determinants and political will

Although we have largely focused on health interventions, this should not be misconstrued as downplaying the importance of factors such as education, social development, economic and sex equality, and feudal power structures.20 Interventions related to some of these determinants would normally be implemented by sectors other than health but are critical to supporting public health interventions.

In addition, several elements in health sector planning such as devolution and democratisation of decision making, governance, and reform are critical to progress in the region. Our analysis shows that relatively low levels of spending on health (in comparison with military expenditure) and ineffective health sector governance are important correlates of child survival in the poorest countries of the region. This suggests that much can be done, even with limited resources. Indeed, Morocco and Egypt have made remarkable gains in child survival over the past decade with relatively limited resources (box).

Conclusions

Our review of child survival has several limitations. Our estimates of the effect of interventions are largely derived from small efficacy studies and have wide confidence intervals. However, we do not think that this detracts from the main message that much can be done with existing knowledge and resources. Because of the focus on survival, we have not discussed the emerging issues of mental health and child development, urbanisation, environmental change, and lifestyle issues such as obesity. The high rates of consanguinity and inherited disorders in the region will also emerge as public health issues once child mortality drops. We believe, however, that our data point to an unacceptable persistent burden of child mortality from common disorders in some countries in the region. In most instances, these deaths are largely preventable by well established interventions. These existing interventions, as well as the promising new targeted strategies, must be delivered to all those who need them most. This will require concerted efforts by public health policy makers, development agencies, and civic societies to garner resources for child health. Not only must these interventions be based on robust evidence but their implementation in health systems must also be part of a learning process.

Morocco's success story

Morocco has a population of 30 million and mortality for children under 5 years is 43/1000 live births. Mortality has fallen sharply since Morocco became independent, averaging 6% a year. Despite numerous challenges and a per capita annual income of $1540, the government has been able to introduce several high quality health programmes:

Immunisation—A national programme was started in 1981 and reinforced in 1987 comprising systematic vaccinations in health posts, annual national vaccination days, and mobile teams going four times a year to rural areas. Current vaccine coverage exceeds 95%

Diarrhoeal diseases—A control programme was initiated in 1979 and extended in 1990

Acute respiratory infections—Programme started in 1997

Nutrition programme includes promotion of exclusive breast feeding and complementary feeding; monitoring of child growth; prevention of vitamin D, vitamin A, and iron deficiencies; and detection and treatment of severe malnutrition. Vitamin A is also distributed at time of vaccination.

Since 1998 many of these vertical programmes have been brought together in the integrated management of sick children strategy. The decline in mortality has been faster for children aged 1-4 years than for infants. A recent evaluation concluded that vaccine preventable diseases contributed to 23% of the total fall in mortality, diarrhoea and malnutrition to 33%, and other infectious diseases to 29%. However, mortality for accidents, acute respiratory infection in infancy, and some neonatal conditions (birth trauma and prematurity) has not changed much. These findings have led to the recent inclusion of the neonatal period in the national strategy for management of sick children.

Supplementary Material

Further details of the review are on bmj.com

Further details of the review are on bmj.com

We thank Arjumand Rizvi for help with the analysis of the effect of interventions and Mohammad Afzal for additional information on research funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors and sources: This paper is part of a larger analysis of child health and survival in the Eastern Mediterranean region and the global evidence base of interventions. ZAB conceived of the idea for the article and analysis, collected the primary information, and wrote the first draft. All co-authors contributed to the analytical and paper writing process as well as contributing specific information as required. ZAB is guarantor.

References

- 1.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet 2003;361: 2226-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 2003;362: 65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? where? why? Lancet 2005;365: 891-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L, Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet 2005;365: 977-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. World health report 2005. Make every mother and child count. www.who.int/whr/2005/en/index.html (accessed 26 Jul 2006).

- 6.Task Force on Child Health and Maternal Health. Who's got the power? Transforming health systems for women and children. New York: UN Millennium Project, 2005. www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/tf_health.htm (accessed 26 Jul 2006).

- 7.World Health Organization. Statistics. www.who.int/research/en/ (accessed 27 Jul 2006).

- 8.Unicef. Monitoring the status of women and children. www.childinfo.org/ (accessed 26 Jul 2006).

- 9.Bhutta ZA, Khan I, Salat S, Raza F, Ara H. Reducing length of stay in hospital for very low birth weight infants by involving mothers in a stepdown unit: an experience from Karachi (Pakistan). BMJ 2004;329: 1151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A, Pang T, Bhutta Z, Hyder AA, et al. Overcoming health-systems constraints to achieve the millennium development goals. Lancet 2004;364: 900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Community based initiatives: Success stories from the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2006. www.emro.who.int/cbi/pdf/CBI_SuccessStories.pdf (accessed 20 Sep 2006).

- 12.Shadpour K. Primary health care networks in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterranean Health J 2000;6: 822-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haines A, Sanders D, Rowe AK, Lawn J, Jan S, Walker D, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics 2005;115(suppl): 519-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bang AT, Baitule SB, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Bang RA. Low birth weight and preterm neonates: can they be managed at home by mother and a trained village health worker? J Perinatol 2005;25(suppl 1): S72-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryce J, Victora CG, MCE-IMCI Technical Advisors. Ten methodological lessons from the multi-country evaluation of integrated management of childhood illness. Health Policy Plan 2005;20(suppl 1): i94-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Victora CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health 2004;94: 400-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhutta ZA, Lassi S. Child health: how can health research make a difference? Global Forum Update on Research for Health 2005:107-11. www.globalforumhealth.org/filesupld/global_update1/GlobalUpdate4.pdf (accessed 26 Jul 2006).

- 19.Smithuis F, Kyaw MK, Phe O, Aye KZ, Htet L, Barends M, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus artesunate-mefloquine in falciparum malaria: an open-label randomized comparison. Lancet 2006;367: 2075-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health and health equity in the EMR/MENA region, 2006. www.who.int/social_determinants/resources/emro_workshop_rpt.pdf (accessed 15 Sep 2006).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.