Abstract

In the present study we investigated whether apoptosis and phagocytosis are regulated by nuclear factor (NF)-κB in a model of chronic inflammation. The subcutaneous implant of λ-carrageenin-soaked sponges elicited an inflammatory response, characterized by a time-related increase of leukocyte infiltration into the sponge and tissue formation, which was inhibited by simultaneous injection of wild-type oligodeoxynucleotide decoy to NF-κB. Molecular and morphological analysis performed on infiltrated cells demonstrated: 1) an inhibition of NF-κB/DNA binding activity; 2) an increase of polymorphonuclear leukocyte apoptosis correlated either to an increase of p53 or Bax and decrease of Bcl-2 protein expression; and 3) an increase of phagocytosis of apoptotic polymorphonuclear leukocytes by macrophages associated with an increase of transforming growth factor-β1 and decrease of tumor necrosis factor-α as well as nitrite/nitrate production. Our results, showing that blockade of NF-κB by oligodeoxynucleotide decoy increases inflammatory cell apoptosis and phagocytosis, may contribute to lead to new insights into the mechanisms governing the inflammatory process.

The current paradigm indicates that the resolution of inflammation is an active process regulated by signals able to control leukocyte trafficking as well as gene expression that accompanies apoptosis and phagocytosis.1–3 The transition from acute to chronic inflammation occurs when these signals might be absent or become dysregulated, although the mechanisms underlying the development of chronic inflammation are primarily undefined. In the last years numerous studies in vitro have shown that apoptosis and phagocytosis play a key role in promoting the resolution of inflammation.4 Polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), the first cells infiltrating into the inflamed site, are constitutively programmed to undergo apoptosis, subsequently recognized and ingested by neighboring macrophages.5,6 Moreover, a rapid and safe clearance by macrophages prevents the secondary necrosis of apoptotic cells, with associated release of damaging intracellular contents that can amplify the inflammatory response.1 While undergoing apoptosis PMNs lose membrane phospholipid symmetry resulting in early externalization of signals, including phosphatidylserine, which enhance their phagocytosis.7–10 It is the recognition of these signals by macrophages that actively inhibits the release of proinflammatory mediators such as in favor of anti-inflammatory mediators including transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1),11–13 although the mechanism that accounts for this phenomenon remains to be explored. Indeed, disorder of apoptosis leading to leukocyte longevity as well as defective clearance of apoptotic cells has been suggested to contribute to the development of chronic inflammation.14–16 It is well known that nuclear factor (NF)-κB plays a central role in inflammation through its ability to induce transcription of proinflammatory genes.17 Many inflammatory mediators that activate NF-κB and their expression are, in turn, controlled by this transcription factor to regulate leukocyte trafficking and activation.18 NF-κB activation is also involved in regulating the apoptotic program of inflammatory cells.19,20 The majority of evidences points to a relationship between NF-κB activity and protection of cells from apoptosis21–23 and several mechanisms are implicated in the anti-apoptotic role of NF-κB.24,25 An enhanced apoptosis observed after the NF-κB inhibition has been reported widely.26–30 In the last few years some studies also have focused on the role of NF-κB in phagocytosis.31–33 The molecular mechanisms and biochemical pathways that regulate apoptosis and the clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytosis in vivo remain poorly understood, although their modulation represents a potential therapeutic target in the control of inflammatory disease.34,35 In the present study, we investigated whether these two critical events of inflammation are controlled by NF-κB in a subcutaneous carrageenin-soaked sponge implant model in the rat. For this purpose, we used synthetic double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) decoy to NF-κB capable of blocking the transcriptional activity of NF-κB.36–39

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Harlan, Udin, Italy), weighing 180 to 250 g, were used in all experiments. Animals were provided with food and water ad libitum. The light cycle was automatically controlled (on 7 hours; off 19 hours) and the room temperature thermostatically regulated to 22 ± 1°C with 60 ± 5% humidity. Before the experiments, animals were housed in these conditions for 3 to 4 days to become acclimatized. Animal care was in accordance with the Italian and European regulations on protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes.

Sponge Implant Model

Sponge implant in the rat was performed as previously described.40 Briefly, two polyether cylindrical sponges (190 mm in length, 10 mm in diameter) for the same treatment were implanted subcutaneously on the back of rats under general anesthesia. Sponges and surgery tools were autoclaved. λ-Carrageenin (1% w/v) was prepared in sterile pyrogen-free saline and endotoxin contamination was evaluated by the Limulus test. After implant, 0.5 ml of 1% λ-carrageenin was injected into each sponge in the presence or absence of wild-type ODN (W.T., 20 μg/site) or mutant ODN (Mut, 20 μg/site) decoy using saline as vehicle. After sponge implant (1, 3, and 5 days) rats were sacrificed in an atmosphere of CO2. The granulomatous tissue around the sponge was dissected and weighted.

Collection of Cells and Exudate

The sponges were removed and centrifuged at 400 × g for 15 minutes. The exudate volume recovered from the sponge was measured and stored at −20°C. The cell pellet was suspended in 1 ml of saline and total cell amount was counted by phase-contrast microscopy. In some experiments total cells (1 × 106) were resuspended in 100 μl of 5% bovine serum albumin/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 10 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-granulocyte antibody (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 15 minutes in the dark at room temperature. The cells were washed and resuspended in 500 μl of PBS and then analyzed by a FACScan 30 (BD) flow cytometer. A threshold was set for FSc to exclude the debris and white blood cell populations were identified using a SSc/Fl-1 or SSc/FSc dual-parameter plot. Cytosolic and nuclear extracts of cells collected from sponges were prepared as previously described.28 Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad (Milan, Italy) protein assay kit.

TGF-β1, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α, and Nitrite/Nitrate (NOx) Determination

The accumulation of TGF-β1 and TNF-α in the inflammatory exudate was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TGF-β1, Emax ImmunoAssay System; Promega, Madison, WI; TEMA Ricerche, Milan, Italy). The amount of NOx, stable metabolites of nitric oxide, was determined as previously described.41

Histological and Immunohistochemical Investigations

Explants were fixed in formol-methanol (9:1, v/v) solution at 4°C for 24 hours. After dehydration in an ethanol series and infiltration with xylol, paraffin wax sections were cut at 4 to 6 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Mallory’s triple stain. The cellular migration into the sponge was evaluated by counting 100 cells per well at ×1000 magnification under oil immersion. Immunostaining of sections was performed for p65, p53, Bax, and Bcl-2 antibodies using a streptavidin-biotin immunoperoxidase technique. Chromogen reaction was developed with diaminobenzidine solution (DAKO, Milan, Italy). Phagocytosis was evaluated by counting 200 to 300 macrophages per well at ×1000 magnification under oil immersion. Results were expressed as percentage of monocyte-derived macrophages (MΦ) containing at least one ingested apoptotic PMN (phagocytic percent).

Ultrastructure Investigations

Immediately after explant the granuloma was rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then immersed in a mixture of 2% glutaraldehyde and 1% formaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L of phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 2 hours. The specimens were divided and used for investigations by scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

After primary fixation the specimens were dehydrated in acetone and dried in a critical point drier CPD010 (Balzers Union, Liechtenstein) with carbon dioxide. The specimens were mounted on the aluminum mounts and sputtered in Coating Unit E5100 (Polaron, UK) with gold-palladium and examined under a Tesla BS340 microscope. The pictures were taken and additionally enlarged to the desired magnification at ×3000.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

During the primary fixation the samples were divided into ∼1- to 2-mm3 blocks for the better fixation. The primary fixation was followed by a 2-hour secondary fixation in 2% osmium tetraoxide in the 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer. After dehydration in acetone with uranium acetate and embedding in Durcupan ACM (Fluka, Milan, Italy), semi-thin toluidine blue-stained sections were made for the control in the light microscope. From the selected areas target ultra-thin section were cut, stained by uranium acetate and lead citrate, and examined and photographed under the transmission electron microscope (Opton 109, Zeiss, Milan, Italy) at the accelerating voltage 80 kV. The pictures were taken at the primary magnification of ×1000 to ×50,000 and additionally enlarged to desired magnification.

Apoptosis Analysis

PMN apoptosis was evaluated through morphological criteria by light microscopy. Criteria used to diagnose apoptosis included chromatin aggregation, cytoplasmic vacuolation, and/or cell shrinkage.5 Moreover, analysis of apoptosis was performed by flow cytometry using annexin V that binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells. To measure granulocyte apoptosis, 1 × 106 cells were incubated, in double staining, with annexin V phycoerythrin-conjugated (Alexis, San Diego, CA) plus the fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-rat granulocyte monoclonal antibody (Pharmingen/Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) in 100 μl of binding buffer containing 10 mmol/L Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.5, 140 mmol/L NaCl, and 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2 for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Then 400 μl of the same buffer were added to each sample and the cells were analyzed by a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer. The percentage of annexin-positive cells was referred to the gated (FL1/SSC) granulocyte.

Transcription Factor Decoy Oligonucleotides

Plain double-stranded ODN decoys to NF-κB were prepared by annealing of sense and anti-sense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides in vitro in 1× annealing buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mmol/L MgCl2,and 50 mmol/L NaCl). The mixture was heated at 100°C for 12 minutes and allowed to cool to room temperature slowly throughout 18 hours.

The sequence of ODN decoy to NF-κB (W.T. ODN) used was: wild-type NF-κB consensus sequence 5′-GAT CGA GGG GAC TTT CCC TAG C-3′ and 3′-CTA GCT CCC CTG AAA GGG ATC G-5′; mutant NF-κB consensus sequence with a mutation of the bolded bases (GGAC to AAGC) of wild-type NF-κB consensus sequence (Mut ODN) 5′-GAT CGA GGA AGC TTT CCC TAG C-3′ and 3′-CTA GCT CCT TCG AAA GGG ATC G-5′.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

Double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the NF-κB recognition sequence (5′-CAACGGCAGGGGAATCTCCCTCTCCTT-3′) as well as W.T. ODN were end-labeled with 32P-γ-ATP. Nuclear extracts containing 5 μg of protein were incubated for 15 minutes with radiolabeled oligonucleotides (2.5 to 5.0 × 104 cpm) in a reaction buffer as previously described.28 The specificity of the NF-κB/DNA binding was determined by a competition reaction in which a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled wild-type, mutant, or Sp-1 oligonucleotide was added to the binding reaction 15 minutes before the radiolabeled probe. The specificity of the ODN/DNA binding was determined by competition reaction in which a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled wild-type or mutant ODN was added to the binding reaction 15 minutes before the radiolabeled probe. In the supershift assay, antibodies reactive to p52, c-Rel, RelB, p50, or p65 proteins were added to the reaction mixture 15 minutes before the addition of the radiolabeled NF-κB probe. Nuclear protein-oligonucleotide complexes were resolved by electrophoresis on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE (Tris borate-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) buffer at 150 V for 2 hours at 4°C. The gel was dried and autoradiographed with intensifying screen at −80°C for 20 hours. Subsequently, the relative bands were quantified by densitometric scanning of the X-ray films with a GS-700 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad) and a computer program (Molecular Analyst; IBM).

Western Blot Analysis

Immunoblotting analysis of anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2, anti-p53, anti-histone 1, anti-p50, and anti-p65 was performed on cytosolic or nuclear fraction, respectively, as previously described.28 Cytosolic and nuclear fraction proteins were mixed with gel loading buffer in a ratio of 1:1, boiled, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g. Protein concentration was determined and equivalent amounts (50 μg) of each sample were electrophoresed in a 8% discontinuous polyacrylamide minigel. The proteins were transferred onto nitro-cellulose membranes, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad). The membranes were saturated by incubation at room temperature for 2 hours with 10% nonfat dry milk in PBS and then incubated with (1:1000) anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2, anti-p53, anti-p50, and anti-p65 at 4°C overnight. The membranes were washed with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and then incubated with anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-goat immunoglobulins coupled to peroxidase (1:1000) (DAKO, Milan, Italy). The immunocomplexes were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham, Milan, Italy). The membranes were stripped and reprobed with β-actin antibody to verify equal loading of proteins. Subsequently, the relative expression of Bax, Bcl-2, p53, p50, and p65 in cytosolic and nuclear fraction was quantified by densitometric scanning of the X-ray films with a GS 700 Imaging Densitometer (Bio-Rad) and a computer program (Molecular Analyst, IBM).

Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated by one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni-corrected P value for multiple comparison test. The level of statistically significant difference was defined as P < 0.05. The fold increase was calculated by dividing the combination value by sum of individual values.

Reagents

Oligonucleotide synthesis was performed to our specifications by Tib Molbiol, Boehringer-Mannheim (Genova, Italy). 32P-γ-ATP was from Amersham (Milan, Italy). Poly dI-dC was from Boehringer-Mannheim (Milan, Italy). Anti-p50, anti-p65, anti-p52, anti-c-Rel, anti-RelB, and anti-histone 1 antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Milan, Italy). Anti-Bax, anti-Bcl-2, and anti-β-actin antibodies were from Oncogene (Milan, Italy). Anti-p53 antibody was from Pharmingen/Becton Dickinson (San Diego, CA). PBS and Tween 20 were from ICN (Milan, Italy). Nonfat dry milk was from Applichem (Darmstadt, Germany). All other reagents were from Sigma (Milan, Italy).

Results

ODN Decoy to NF-κB Reduces Infiltrating Leukocytes and Granulomatous Tissue Formation

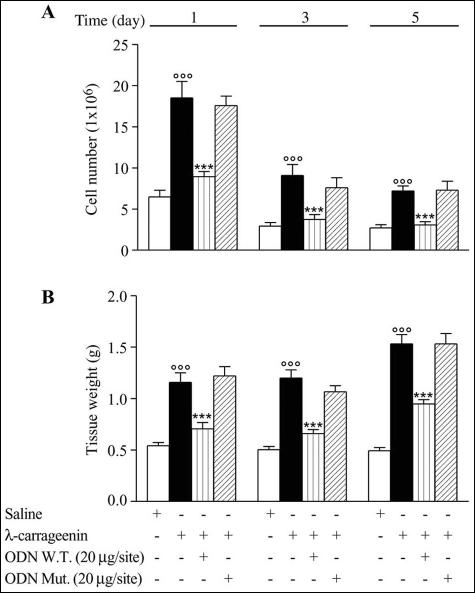

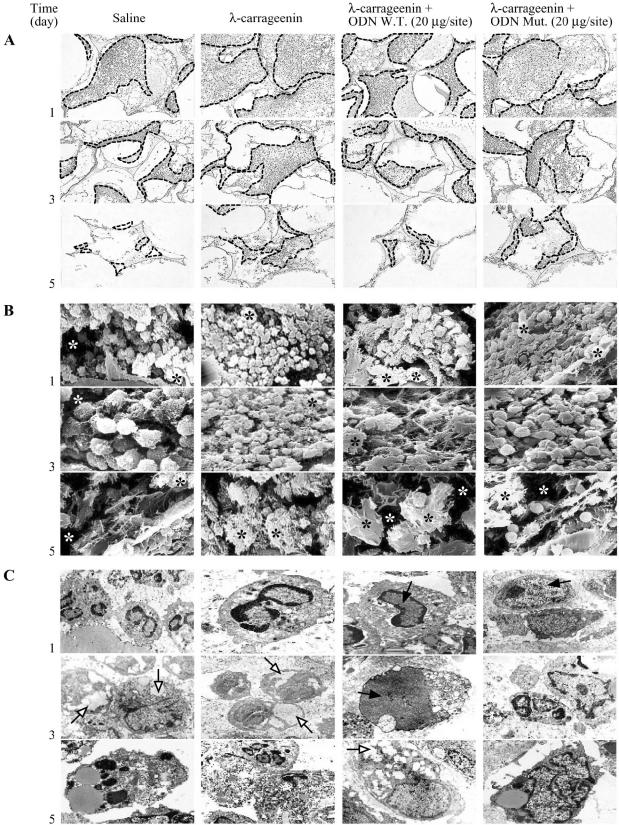

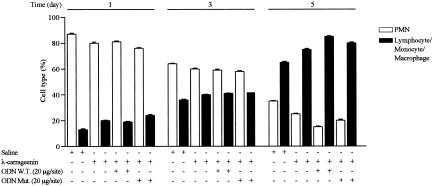

λ-Carrageenin (1%) induced a significant increase in infiltrating leukocytes and granulomatous tissue formation after 1, 3, and 5 day (versus saline). The exudate volume did not change throughout the time and treatment. The total number of infiltrated leukocytes into the sponge was highest at day 1, and then declined time dependently. Conversely, tissue weight was further increased up to day 5. Local injection of W.T. ODN decoy to NF-κB (20 μg/site), but not Mut ODN decoy (20 μg/site), inhibited leukocyte infiltration (by 51.65 ± 0.62%, 59.34 ± 0.45%, and 57.36 ± 0.4%, P < 0.0001; n = 15 to 20 sponges from 9 to 10 rats) and granuloma formation (by 38.96 ± 0.06%, 45.0 ± 0.04%, and 38.03 ± 0.09%, P < 0.0001; n = 15 to 20 sponges from 9 to 10 rats) as compared to carrageenin alone at time points considered (Figure 1, A and B). The migration and concomitant tridimensional organization of leukocytes into the sponge was studied by light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy, respectively (Figure 2, A and B). A first identification of cell activation status as well as apoptosis and phagocytosis was performed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2C). We observed that W.T. ODN decoy treatment caused a reduced migration accompanied with changed arrangement of cell populations in the sponge. Particularly, transmission electron microscopy analysis indicated a marked leukocyte activation associated with pictures of apoptosis and phagocytosis. The inflammatory cell profile, determined by light microscopy, is illustrated in Figure 3. The PMN contribution to the infiltrate was maximal on day 1 and declined after 3 days, whereas lymphocyte/monocyte/macrophage infiltration increased progressively up to 5 days. The W.T. ODN decoy did not affect the cellular profile. However, flow cytometry analysis confirmed the composition of the cells infiltrated into the sponge using both SSc/FL-1 (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-granulocyte antibody) and SSc/FSc dual-parameter plots. The profile of leukocytes from the λ-carrageenin-treated sponge was the following: 90% granulocytes, 4% lymphocytes, and 6% monocytes/macrophages on day 1; 64% granulocytes, 15% lymphocytes, and 21% monocytes/macrophages on day 3. These results were comparable to those obtained from the saline-, W.T. ODN-, and Mut ODN-treated sponges. Unfortunately, we were not able to analyze the samples on day 5 because the cells apparently have lost the typical FSc and SSc patterns.

Figure 1.

Leukocyte infiltration (A) and granulomatous tissue formation (B). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 15 to 20 sponges from 9 to 10 rats. °°°, P < 0.0001 versus saline; ***, P < 0.0001 versus λ-carrageenin alone.

Figure 2.

Morphological summary depicting cell migration, tridimensional organization, and activation status in the sponge after treatments. A: Light microscopy: relationship between spaces invaded by cells (outlined areas) and exudate as well as debris. B: Scanning electron microscopy: presence of cells organized even in clusters with debris (black asterisk) and exudate (white asterisk) areas. C: Transmission electron microscopy: ultrastructural features of cell populations with cytosol suggestive of phagocytosis as well as autophagy (open arrows) and nuclei involution (filled arrows) Fields are representative of three experiments. Original magnifications: ×100 (A); ×2400 (B); ×6400 to 8900 (C).

Figure 3.

Leukocyte population infiltrated into the sponge. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three sponges from three rats. Cell counting was performed as reported in Materials and Methods.

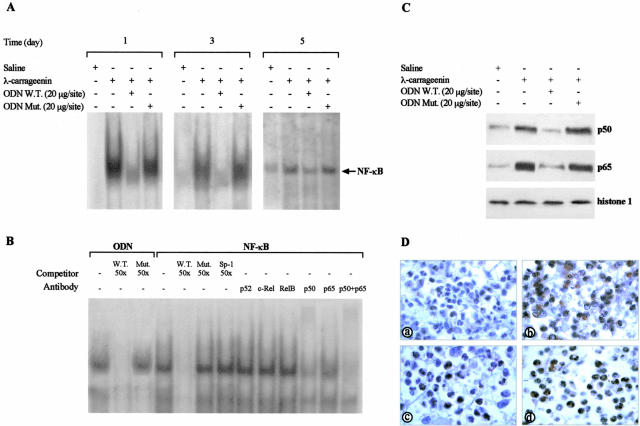

NF-κB Activation in Inflammatory Cells

The granuloma formation and cellular infiltrate were correlated with NF-κB activation. To detect NF-κB/DNA binding activity nuclear extracts from total leukocytes were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay. A basal level of NF-κB/DNA activity was detected in nuclear extracts of cells from saline-treated sponges harvested on days 1, 3, and 5 after implant. The DNA binding activity significantly increased in nuclear extracts of cells obtained from carrageenin-treated sponges as compared to saline. Local injection of the W.T. ODN decoy to NF-κB (20 μg/site) caused a significant reduction of carrageenin-induced NF-κB/DNA binding activity (by 41.22 ± 4.4%, 69.4± 3.7%, and 66.7 ± 2.1%, P < 0.001; n = 6) whereas the Mut ODN decoy (20 μg/site) had no effect (Figure 4A). The composition of the NF-κB complex activated by carrageenin was determined by competition and supershift experiments (Figure 4B). The specificity of the W.T. ODN/DNA binding complex was demonstrated by the complete displacement of the W.T. ODN/DNA binding in the presence of a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled W.T. ODN probe (W.T., 50×) in the competition reaction. In contrast a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled Mut ODN probe (Mut, 50×) had no effect on this DNA binding activity. The specificity of NF-κB/DNA binding complex was demonstrated by the complete displacement of the NF-κB/DNA binding in the presence of a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled NF-κB probe (W.T., 50×) in the competition reaction. In contrast a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled mutated NF-κB probe (Mut, 50×) or Sp-1 oligonucleotide (Sp-1, 50×) had no effect on this DNA binding activity. The composition of the NF-κB complex activated by carrageenin was determined by using specific antibodies against p52, c-Rel, RelB, p50, and p65 subunits of NF-κB proteins. Addition of either anti-p50 or anti-p65 and their combination to the binding reaction resulted in a marked reduction of NF-κB band intensity, suggesting that the NF-κB complex contained p50 and p65 heterodimers. NF-κB activation was confirmed by Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis on day 1 (Figure 4, C and D) as well as on days 3 and 5 (data not shown). In carrageenin-treated sponges the p50 and p65 nuclear levels were increased as compared to saline. Administration of W.T. ODN decoy, but not Mut ODN decoy, preventing nuclear translocation, reduced both p50 and p65 band intensity (by 70.82 ± 0.2% and 83.57 ± 0.9%, P < 0.0001; n = 3, respectively). Both PMN and mononuclear cells from carrageenin-treated sponges exhibited higher positivity for p65 compared to W.T. ODN decoy and saline.

Figure 4.

A: Representative electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing NF-κB/DNA binding activity in nuclear extract from inflammatory cells. Data are from a single experiment and are representative of six separate experiments. B: Characterization of NF-κB/DNA complex was performed on λ-carrageenin-treated cells harvested on 1 day after implant. In competition reaction nuclear extracts were incubated with radiolabeled W.T. ODN probe in the absence or presence of identical but unlabeled oligonucleotide (W.T., 50×) or mutated nonfunctional ODN probe (Mut, 50×). In addition, nuclear extracts were incubated with radiolabeled NF-κB probe in absence or presence of: identical but unlabeled oligonucleotide (W.T., 50×), mutated nonfunctional NF-κB probe (Mut, 50×) or unlabeled oligonucleotide containing the consensus sequence for Sp-1 (Sp-1, 50×). In supershift experiments nuclear extracts were incubated with antibodies against p52, c-Rel, RelB, p50, and p65 15 minutes before incubation with radiolabeled NF-κB probe. Data are from a single experiment and are representative of six separate experiments. C: Representative Western blot of p50 and p65 nuclear level from cells collected on 1 day after implant. Histone 1 expression is shown as control. Data are from a single experiment and are representative of three separate experiments. D: Immunohistochemical analysis of p65 protein expression in cells from saline (a), λ-carrageenin (b), W.T. ODN (c), and Mut ODN (d) decoy-treated sponges harvested on 1 day after implant. Fields are representative of three experiments. Original magnifications, ×320 (D).

Inhibition of NF-κB Increases Leukocyte Apoptosis

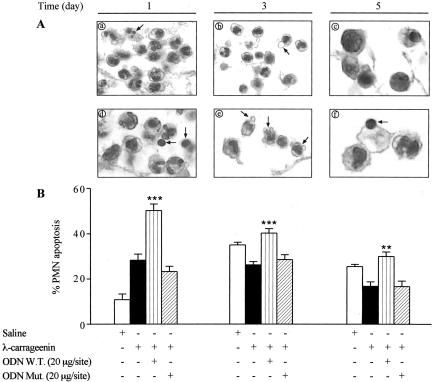

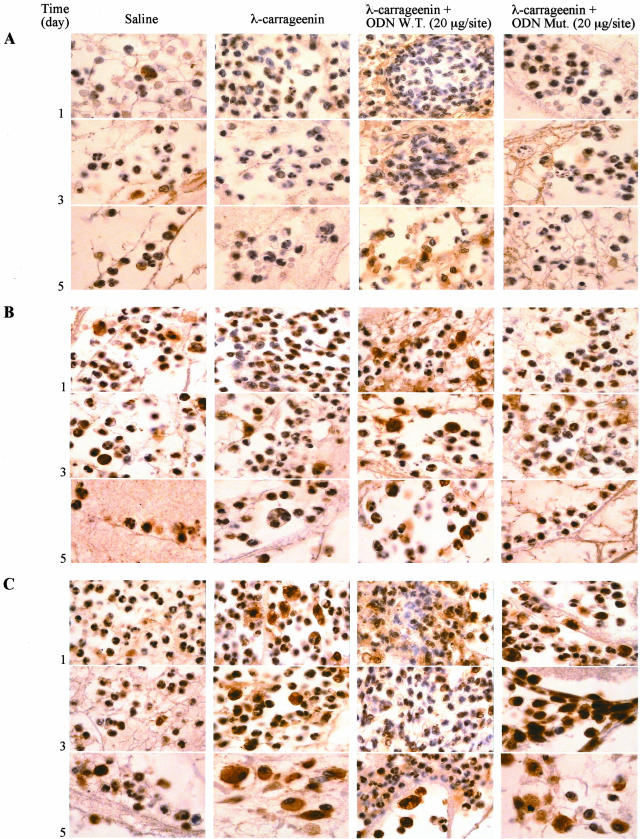

Leukocytes harvested on days 1, 3, and 5 after implant were examined for apoptosis using morphological criteria. PMNs from W.T. ODN decoy-treated sponges visualized by phase-contrast microscopy were indicative of apoptosis (Figure 5A; d, e, and f) as compared to carrageenin alone (Figure 5A; a, b, and c). In addition, we examined PMN apoptosis using annexin V staining by flow cytometry. As indicated in Figure 5B, PMNs isolated from saline-treated sponges exhibited on day 1 a low incidence of apoptosis with a substantial enhancement on days 3 and 5; conversely, carrageenin induced PMN apoptosis that was significantly increased by treatment with W.T. ODN decoy to NF-κB (20 μg/site) (by 1.8-, 1.5-, and 1.8-fold) at the time points studied. Mut ODN decoy (20 μg/site) had no effect. The percentage of apoptotic cells would be correlated with the total number of leukocytes infiltrated into the sponge. The expression of both p53 and Bax proapoptotic protein as well as Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic protein in infiltrated leukocytes was determined by Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis. A significant increase in protein expression of both p53 (by 2.4-, 2.7-, and 3.9-fold, P < 0.0001; n = 3) and Bax (by 2.4-, 2.7-, and 4.2-fold, P < 0.0001; n = 3) was detected in cells from W.T. ODN decoy-treated sponges compared to carrageenin alone. Conversely, carrageenin induced the appearance of a marked Bcl-2 band, the intensity of which was reduced (by 69.93 ± 0.5%, 60.34 ± 0.3%, and 69.70 ± 0.2%, P < 0.0001; n = 4) by treatment with W.T. ODN decoy. Mut ODN decoy had no effect (Figure 6). These evidences were corroborated by immunohistochemical analysis showing a marked positivity in PMNs, nevertheless a positivity even was present in lymphocytes/monocytes/macrophages (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

A: Morphological features of apoptosis (arrows) in PMNs from λ-carrageenin (a–c) and W.T. ODN decoy-treated sponges (d–f). Fields are representative of three experiments. B: PMN apoptosis was evaluated by FACS using annexin V staining. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three to five sponges from three to five rats. **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001 versus λ-carrageenin alone. Original magnifications, ×320 (A).

Figure 6.

Representative Western blot of p53 (A), Bax, and Bcl-2 (B) protein expression in nuclear and cytosolic extracts from inflammatory cells. Histone 1 and β-actin expression are shown as control, respectively. Data are from a single experiment and are representative of three to four separate experiments.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical summary of p53 (A), Bax (B), and Bcl-2 (C) protein expression in inflammatory cells after treatments. Fields are representative of three experiments. Original magnifications, ×320.

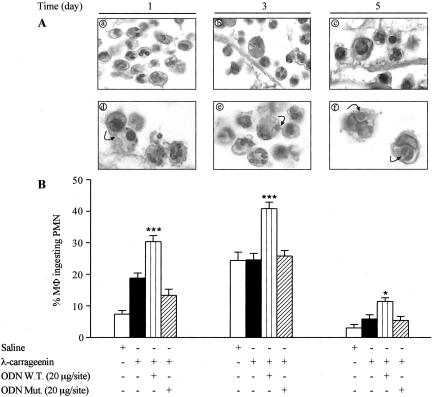

Inhibition of NF-κB Increases Leukocyte Phagocytosis

We also determined macrophage phagocytosis on 1, 3, and 5 days after implant by histological analysis. The increased incidence of PMN apoptosis was associated with a substantial increase of phagocytosis (by 1.6-, 1.7-, and 1.9-fold, P < 0.0001, P < 0.05; n = 3) by macrophages from sponges treated with W.T. ODN decoy to NF-κB (20 μg/site) compared to carrageenin alone at the time points studied (Figure 8, A and B). Moreover, the increase in phagocytosis of apoptotic PMNs by W.T. ODN decoy was accompanied by an increased release of TGF-β1 (by fourfold, threefold, and fourfold, respectively) and decreased levels either of TNF-α (by 32%, 43%, and 46%, respectively) or nitrite/nitrate (by 32%, 46%, and 48%, respectively) in the inflammatory exudate at the time points considered (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

A: Morphological appearance of MΦ phagocytosis (arrows) from λ-carrageenin (a–c) and W.T. ODN decoy-treated sponges (d–f). Fields are representative of three experiments. B: Phagocytosis was evaluated as phagocytic percent. Data are expressed as percentage of mean ± SEM of MΦ containing at least one ingested apoptotic PMN (n = 3 sponges from three rats). *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.0001 versus λ-carrageenin alone. Original magnifications, ×320 (A).

Figure 9.

Effect of W.T. ODN decoy on TGF-β1 (A), TNF-α (B), and NOx (C) production by inflammatory exudate. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three experiments in triplicate. °, P < 0.05; °°, P < 0.001; °°°, P < 0.0001 versus saline; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001 versus λ-carrageenin alone.

Discussion

Apoptosis and the clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytosis are complex and intriguing processes orchestrated by a repertoire of cellular signals.4 Although much progress has been made in recent years toward an understanding of how apoptosis and phagocytosis influence each other in vitro, much remains to be understood in vivo. In the study presented here we investigated the role of NF-κB in inflammatory cell apoptosis and phagocytosis using a rat carrageenin-soaked sponge implant. This model allows the possibility to identify and quantify the cellular infiltrate into the sponge as well as freeze activation status throughout time. In preliminary experiments we found that the W.T. ODN decoy to NF-κB reduced both granuloma formation and leukocyte infiltration induced by carrageenin. The morphological observations revealed that mainly leukocytes from the W.T. ODN decoy treated-sponges were PMNs with clear features of apoptosis and macrophages appearing to have ingested PMNs. The reduction of cellular infiltrate was correlated with NF-κB activation. Active NF-κB occurred in either PMNs or lymphocytes/monocytes/macrophages from carrageenin-treated sponges and exhibited higher positivity for p65 in comparison with those from W.T. ODN decoy. It is interesting to note that the cellular profile, with a peak for PMNs on 1 day and for lymphocytes/monocytes/macrophages on 5 days, was not affected by the W.T. ODN decoy treatment. These findings, demonstrating that the W.T. ODN decoy reduces the cellular migration but does not affect the type of cellular population, suggest that NF-κB may represent a key target for safely driving resolution of inflammation. It has been reported that NF-κB inhibition reduces leukocyte adhesion and transmigration.42 Our findings suggest that NF-κB blockade inhibits the number of leukocytes infiltrated into the sponge through the suppression of NF-κB-dependent genes involved in cellular trafficking. Supporting morphological criteria we studied PMN apoptosis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. A high rate of PMN apoptosis was observed after the blockade of NF-κB activation at any examined time, whereas NF-κB activation caused not only an increase of the total number of infiltrated leukocytes but dramatically augmented PMN survival. PMNs isolated from saline-treated sponges exhibited on day 1 a low incidence of apoptosis with a substantial enhancement on day 3 and day 5. The survival of PMNs on day 1 may depend on signals encountered on arrival into the sponge and unlike from λ-carrageenin. The subsequent increase in PMN apoptosis on day 3 and day 5 might allow for their efficient removal by macrophages. The increase of PMN apoptosis by the W.T. ODN decoy was associated with an increase of either p53 or Bax and a decrease of Bcl-2 protein expression. It has been demonstrated that NF-κB and p53 transcriptionally cross-regulate each other’s activity through the competition for co-activators.43,44 Bax expression is increased in certain cells that express the IκBα superrepressor and overexpression of NF-κB inhibits p53-stimulated Bax promoter activity.45 Moreover, Bax has been shown to be involved in p53-dependent apoptosis in vivo.46 Bcl-2 expression is defective in B cells that lack both c-Rel and RelA.47 Thus, it is plausible to speculate that blockage of NF-κB activation induces an increase of PMN apoptosis through up-regulation of p53 activity that, in turn, can activate Bax expression. Taken together our results, showing that NF-κB inhibition causes also a decreased Bcl-2 expression, support the hypothesis that NF-κB contributes to PMN survival promoting inflammation. It is now well established that phagocytes recognize and engulf apoptotic PMNs at an inflammatory site,4 but phagocytes also can promote the induction and execution of apoptosis in target cells.48 Nevertheless, the mechanisms that control phagocytic capacity for the clearance of apoptotic cells are poorly understood. We found that the increased incidence of PMN apoptosis was accompanied by a substantial augmentation of the phagocytic potential by macrophages from sponges treated with W.T. ODN decoy. It has been reported that p53 and Bax expression promote the uptake of apoptotic cells and accelerate the engulfment.49 Our results, showing that NF-κB inhibition up-regulates p53 and Bax expression, suggest that NF-κB even might modulate phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. There is strong evidence that clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages can suppress the inflammatory response inducing an anti-inflammatory phenotype.4 We observed that the enhancement of phagocytosis was accompanied by a concomitant increase of TGF-β1 and a decrease of both TNF-α and nitrite/nitrate level in inflammatory exudate. It has been shown that TGF-β1 blocks inflammatory cytokine production by macrophages through inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB.50 It is possible that NF-κB inhibition enhancing apoptosis and phagocytosis leads to increased production of TGF-β1 that, in turn, may contribute to inhibit NF-κB thereby potentiating macrophage phagocytosis. In conclusion, this is the first in vivo evidence that NF-κB inhibition reduces cellular migration and induces PMN apoptosis accompanied by augmentation of phagocytic capacity of macrophages at inflamed site. Further studies will be needed to define the mechanisms underlying the enhancement of leukocyte apoptosis and phagocytosis after NF-κB blockade. Our observations indicating NF-κB as a regulator of inflammatory cell fate, at least in part, might be important to understanding mechanisms governing inflammatory process and, consequently, develop more effective therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. M.L. Del Basso De Caro for assistance and technical support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to R. Carnuccio, Dipartimento di Farmacologia Sperimentale, Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II,” Via D. Montesano, 49, 80131 Napoli, Italy. E-mail: carnucci@unina.it.

Supported by the Italian Government and the Associazione Italiana Ricerca Cancro.

References

- Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:375–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi SD, Voyich JM, Buhl CL, Stahl RM, DeLeo FR. Global changes in gene expression by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes during receptor-mediated phagocytosis: cell fate is regulated at the level of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6901–6906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092148299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi SD, Voyich JM, Somerville JA, Braughton KR, Malech HL, Musser JM, DeLeo FR. An apoptosis-differentiation program in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes facilitates resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:315–322. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev. 2002;2:965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J, Wyllie AH, Henson JE, Walport MJ, Henson PM, Haslett C. Macrophage phagocytosis of aging neutrophils in inflammation. Programmed cell death in the neutrophil leads to its recognition by macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:865–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI113970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J, Fadok VA. Corpse clearance defines the meaning of cell death. Nature. 2000;407:784–788. doi: 10.1038/35037722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Frasch SC, Warner ML, Henson PM. The role of phosphatidylserine in recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:551–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Rose DM, Pearson A, Ezekewitz RAB, Henson PM. A receptor for phosphatidylserine-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. Nature. 2000;405:85–90. doi: 10.1038/35011084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Heinisch I, Ross E, Shaw K, Buckley CD, Savill J. Apoptosis disables CD31-mediated cell detachment from phagocytes promoting binding and engulfment. Nature. 2002;418:200–203. doi: 10.1038/nature00811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg S, Grinstein S. Phagocytosis and innate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:136–145. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(01)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Freed PW, Westcott JY, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-β, PGE2 and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–898. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PP, Fadok VA, Bratton D, Henson PM. Transcriptional and translational regulation of inflammatory mediator production by endogenous TGF-β in macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:6164–6172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh M-LN, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-β secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern M, Savill J, Haslett C. Human monocyte-derived macrophage phagocytosis of senescent eosinophils undergoing apoptosis. Mediation by alpha v beta 3/CD36/ thrombospondin recognition mechanism and lack of phlogistic response. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:911–921. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PR, Carugati A, Fadok VA, Cook HT, Andrews M, Carroll MC, Savill J, Henson PM, Botto M, Walport MJ. A hierarchical role for classical pathway complement proteins in the clearance of apoptotic cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000;3:359–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franc NC. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in mammals, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Front Biosci. 2002;7:1298–1313. doi: 10.2741/A841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Williams-Skipp C, Tao Y, Schleicher MS, Cano LL, Duke RC, Scheinman RI. NF-κB functions as both a proapoptotic and antiapoptotic regulatory factor within a single cell type. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:570–582. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal BB. Apoptosis and nuclear factor-κB: a tale of association and dissociation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Antwerp DJ, Martin SJ, Kafri T, Green DR, Verma IM. Suppression of TNF-α-induced apoptosis by NF-κB. Science. 1996;274:787–789. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Mayo MW, Korneluk RG, Goeddel DV, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-κB antiapoptosis: induction of TRAF1 and TRAF2 and c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 to suppress caspase-8 activation. Science. 1998;281:1680–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Nguyen DU, Jin R, Jones J, Cong R, Franzoso G. Induction of gadd45β by NF-κB downregulates pro-apoptotic JNK signalling. Nature. 2001;414:308–313. doi: 10.1038/35104560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Lin A. NF-κB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Lee H, Bellas RE, Schauer SL, Arsura M, Katz D, Fitzgerald MJ, Rothstein TL, Sherr DH, Sonenshein GE. Inhibition of NF-κB/Rel induces apoptosis of murine B cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:4682–4690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Chilvers ER, Lawson MF, Pryde JG, Fujihara S, Farrow SN, Haslett C, Rossi AG. NF-κB activation is a critical regulator of human granulocyte apoptosis in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4309–4318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Acquisto F, De Cristofaro F, Maiuri MC, Tajana G, Carnuccio R. Protective role of nuclear factor kappaB against nitric-oxide apoptosis in J774 macrophages. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:144–151. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara S, Ward C, Dransfield I, Hay RT, Uings IJ, Hayes B, Farrow SN, Haslett C, Rossi AG. Inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation un-mask the ability of TNF-α to induce human eosinophil apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:457–466. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<457::AID-IMMU457>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas DK, Martin KJ, McAlister C, Cruz AP, Graner E, Dai S, Pardee AB. Apoptosis caused by chemotherapeutic inhibition of nuclear factor-κB activation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger CM, Finlay BB. Phagocyte sabotage: disruption of macrophage signalling by bacterial pathogens. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:385–396. doi: 10.1038/nrm1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tridandapani S, Wang Y, Marsh CB, Anderson CL. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol polyphosphate phosphatase regulates NF-κB-mediated gene transcription by phagocytic FcγRs in human myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4370–4378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Punturieri A, Todt J, Sonstein J, Polak T, Curtis JL. Recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic T cells by resident murine tissue macrophages require multiple signal transduction events. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:881–889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Dransfield I, Chilvers ER, Haslett C, Rossi AG. Pharmacological manipulation of granulocyte apoptosis: potential therapeutic targets. TiPS. 1999;20:503–509. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman SJ, Giles KM, Ward C, Rossi AG, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Glucocorticoid-mediated regulation of granulocytes apoptosis and macrophages phagocytosis of apoptotic cells: implications for the resolution of inflammation. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:29–36. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita R, Sugimoto T, Aoki M, Kida I, Tomita N, Moriguchi A, Maeda K, Sawa Y, Kaneda Y, Higaki J, Ogihara T. In vivo transfection of cis element “decoy” against nuclear factor-kappaB binding site prevents myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 1997;3:894–899. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miagkov AV, Kovalenko DV, Brown CE, Didsbury JR, Cogswell JP, Stimpson SA, Baldwin AS, Makarov SS. NF-kappaB activation provides the potential link between inflammation and hyperplasia in the arthritic joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13859–13864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita T, Takeuchi E, Tomita N, Morishita R, Kaneko M, Yamamoto K, Nakase T, Seki H, Kato K, Kaneda Y, Ochi T. Suppressed severity of collagen-induced arthritis by in vivo transfection of nuclear factor-kappaB decoy oligodeoxynucleotides as a gene therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2532–2542. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199912)42:12<2532::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Acquisto F, Ialenti A, Ianaro A, Di Vaio R, Carnuccio R. Local administration of transcription factor decoy oligonucleotides to nuclear factor-kappaB prevents carrageenin-induced inflammation in rat hind paw. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1731–1737. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuvone T, Carnuccio R, Di Rosa M. Modulation of granuloma formation by endogenous nitric oxide. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;265:89–92. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Acquisto F, Ialenti A, Ianaro A, Carnuccio R. Nuclear factor-κB activation mediates inducile nitric oxide synthase expression in carrageenin-induced rat pleurisy. N-S Arch Pharmacol. 1999;360:670–675. doi: 10.1007/s002109900149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Rosenbloom CL, Anderson DC, Manning AM. Selective inhibition of E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression by inhibitors of IkappaB-alpha phosphorylation. J Immunol. 1995;155:3538–3545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadgaonkar R, Phelps KM, Haque Z, Williams AJ, Silverman ES, Collins T. CREB-binding protein is a nuclear integrator of nuclear factor-κB and p53 signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1879–1882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster GA, Perkins ND. Transcriptional cross talk between NF-κB and p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3485–3495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentires-Alj M, Dejardin E, Viatour P, Van Lint C, Froesch B, Reed JC, Merville MP, Bours V. Inhibition of the NF-κB transcription factor increases Bax expression in cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2001;20:2805–2813. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C, Knudson M, Korsmeyer SJ, Van Dyke T. Bax suppresses tumorigenesis and stimulates apoptosis in vivo. Nature. 1997;385:637–640. doi: 10.1038/385637a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann M, O’Reilly LA, Gugasyan R, Strasser A, Adams JM, Gerondakis S. The anti-apoptotic activities of Rel and RelA required during B-cell maturation involve the regulation of Bcl-2 expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:6351–6360. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt B. With a little help from your friends: cells don’t die alone. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E139–E143. doi: 10.1038/ncb0602-e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand UK, Corbach S, Prescott AR, Savill J, Spruce BA. The trigger to cell death determines the efficiency with which dying cells are cleared by neighbours. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8:734–746. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YQ, Malcolm K, Worthen GS, Gardai S, Schiemann WP, Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Cross-talk between ERK and p38 MAPK mediates selective suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines by transforming growth factor-β. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14884–14893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]