Abstract

Lymphocyte infiltration of salivary and lacrimal glands leading to diminished secretion and gland destruction as a result of apoptosis is thought to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome (SS). The cytoskeletal protein α-fodrin is cleaved during this apoptotic process, and a strong antibody (Ab) response is elicited to a 120-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin in the majority of SS patients, but generally not in other diseases in which apoptosis also occurs. Little is known about the anti-α-fodrin autoantibody response on a molecular level. To address this issue, IgG phage display libraries were generated from the bone marrow of two SS donors and a panel of anti-α-fodrin IgGs was isolated by selection on α-fodrin immunoblots. All of the human monoclonal Abs (hmAbs) reacted with a 150-kd fragment and not with the 120-kd fragment or intact α-fodrin, indicating that the epitope recognized became exposed after α-fodrin cleavage. Analysis of a large panel of SS patients (defined by the strict San Diego diagnostic criteria) showed that 25% of SS sera exhibited this 150-kd α-fodrin specificity. The hmAbs stained human cultured salivary acinar cells and the staining was redistributed to surface blebs during apoptosis. They also stained inflamed acinar/ductal epithelial cells in SS salivary tissue biopsies, and only partially co-localized with monoclonal Abs recognizing the full-length α-fodrin. Our study shows that in SS patients, neoepitopes on the 150-kd cleaved product of α-fodrin become exposed to the immune system, frequently eliciting anti-150-kd α-fodrin Abs in addition to the previously reported anti-120-kd Abs. The anti-150-kd α-fodrin hmAbs may serve as valuable reagents for the study of SS pathogenesis and diagnostic analyses of SS salivary gland tissue.

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disease, causing ocular and oral dryness and extraglandular manifestations in three to four million people in the United States alone.1–3 The disease is characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates and destruction of the salivary and lacrimal glands, and systemic production of characteristic autoantibodies. Xerostomia and keratojunctivitis sicca are the common clinical signs, but the San Diego SS diagnostic criteria also require a positive salivary gland biopsy or the presence of autoantibodies to the ribonucleoprotein SS-A/Ro for diagnosis;4 these requirements are not included in the European Economic Committee diagnostic criteria.5,6 The typical histopathological findings of SS salivary and lacrimal gland tissues include glandular attrition in acinar and ductal epithelia concomitant with lymphoplasmacytic infiltration consisting of predominantly CD4+ cells, but also CD8+, B cells, and plasma cells. Several immune and inflammatory effector pathways seem to be implicated in the ongoing pathology of SS, but our understanding of the initiation factors and the precise mechanism of epithelial cell damage and dysfunction remains limited.

Recent studies have indicated a 120-kd fragment of α-fodrin as a potential important autoantigen in the pathogenesis of primary SS in both a mouse model and in humans.7–11 Fodrin is an abundant component of the membrane cytoskeleton of most eukaryotic cells. It is composed of heterodimers of an α (240 kd) and a β (235 kd) subunit that share homologous internal spectrin repeats, but have distinct amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions. The α-fodrin subunit is an actin-binding protein that may be involved in secretion12–14 and has been shown in apoptotic cells to be cleaved by calpain, caspases, and an unidentified protease present in T-cell granule content.15–18 Indeed, treatment of mice with caspase inhibitors prevents induction of SS.19 Autoantibodies to the 120-kd cleavage fragment of α-fodrin have been detected in patients with primary and secondary SS but also in a few systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients without SS.7,9,20–22 Different diagnostic criteria for SS have been used in the various studies and differences in the specificity of 120-kd α-fodrin for SS have been observed, which has rendered the importance of 120-kd α-fodrin as a diagnostic marker controversial.

Here, we have further evaluated the incidence and specificity of anti-α-fodrin Ab response in American SS patients and found a correlation between anti-α-fodrin Ab and SS, but a lower prevalence of anti-120-kd α-fodrin Abs in American versus Japanese SS patients. We also found that ∼25% of SS sera contained Abs against the 150-kd cleavage fragment of α-fodrin. To examine these Abs at a molecular level, we cloned and characterized a panel of hmAbs from SS patients using phage display technology that specifically recognized the 150-kd α-fodrin neoepitope. The anti-150-kd hmAbs were shown to detect 150-kd α-fodrin in apoptotic acinar and ductal salivary gland cells in cell culture, and in SS salivary gland tissue sections, indicating that the hmAbs may be useful diagnostic reagents in SS pathology.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Sera were obtained from 60 SS patients (42 American and 18 Japanese) who fulfilled the San Diego criteria for the diagnosis of SS;23 12 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients; 12 SLE patients, diagnosed based on American College of Rheumatology criteria; and 10 healthy individuals. Bone marrow from two Caucasian American patients with secondary SS (designated SS23 and SS30) were obtained for Ab library construction.

Western Blot Analysis

α-Fodrin was purified from mouse brain tissue using the method of Cheney and colleagues24 yielding >95% purity. Mouse α-fodrin exhibits 94% amino acid sequence identity to human α-fodrin. Coomassie staining of mouse brain α-fodrin separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 10% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) showed an intense band at 240 kd corresponding to intact α-fodrin, but also weaker bands at 180, 150, 120, 80, 50, and 30 kd that corresponded to cleaved α-fodrin because of low levels of constitutive apoptosis, as previously reported.14,17,24,25 Mouse brain α-fodrin separated by SDS-PAGE was also electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore, Bedford, MA), the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.0, for 30 minutes, and incubated with serum (diluted 1:1000 in PBS), human recombinant Fabs (1 to 20 μg/ml) or mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 (Affiniti, Exeter, UK) for 1 hour on a rotator. mAb AA6 predominantly recognizes the 240-kd intact form of α-fodrin, but also the 120- and 150-kd cleaved form of α-fodrin. The membrane was washed three times (10 minutes/wash) in PBS and bound serum Ab was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat Fab anti-human IgG (H+L) Ab (Bio-Rad). A patient serum was used as internal control in each blotting experiment to adjust for band intensity variations between gels. The intensity of the bands was scored (1 to 5) based on quantification by densitometry. Bound human recombinant Fabs were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 Ab and bound mouse mAb detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (both Jackson) diluted in blocking solution and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing for 45 minutes with PBS, membranes were rinsed briefly in MilliQ water, and bound enzyme-labeled Ab was visualized using chemiluminescent substrate (SuperSignal, WestPico; Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and autoradiographic film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). All incubations were done at room temperature. As controls, all experiments were performed using the anti-Ebola virus Fab ELZ510, the anti-HIV-1 gp120 Fab b12, normal sera or by omitting the primary Ab.

Analysis of Patient Sera and Human Fabs by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Mouse brain α-fodrin (2 μg/ml) and ovalbumin (4 μg/ml) (Pierce) were coated onto microtiter wells (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at 4°C overnight. Wells were washed with PBS; blocked with 4% nonfat dry milk in PBS for 30 minutes; and incubated with patient serum (diluted 1:100 and 1:400 in PBS), human Fabs, or mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 for 1 hour at 37°C. Wells were washed six times with PBS-0.05% Tween and bound Ab was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat IgG anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 Ab or anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 Ab (both 1:500 in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS, Pierce) and visualized with nitrophenol substrate (NPP substrate) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) by reading absorbance at 405 nm.

RNA Isolation and Library Construction

RNA was isolated from bone marrow of two American SS patients (designated SS23 and SS30) by a guanidinium isothiocyanate method, as described previously.26 Serum samples from each donor were drawn concomitantly. After reverse-transcription, the γ1 (Fd region) and κ and λ chains were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and phage-display libraries were constructed in the phage-display vector pComb3, as described previously.27–29

Ab Library Selection

Libraries were selected against α-fodrin blotted membrane. Mouse brain α-fodrin was separated by SDS-PAGE using a 10% Tris-HCl gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk/PBS for 30 minutes, the membrane was incubated with phage (1011 pfu) resuspended in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin for 2 hours at room temperature. The membrane was washed and the bound phage, enriched for those bearing antigen-binding surface Fabs, were eluted with 0.2 mol/L glycine-HCl buffer, pH 2.2, as previously described.29–31 The eluted phages were amplified by infection of Escherichia coli and superinfection with M13 helper phage. The libraries were panned for four consecutive rounds with increasing washing stringency (2 × 10 minutes for first panning round and 4 × 10 minutes thereafter). Phagemid DNA, isolated after the last round of panning, was digested with NheI and SpeI restriction endonucleases and religated to excise the cpIII gene. The reconstructed phagemid was used to transform XL1-Blue cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to produce clones secreting soluble Fab fragments. Positive Fab clones were purified from bacterial supernatants by affinity chromatography as previously described.32

Nucleic Acid Sequencing

Nucleic acid sequencing was performed on a 373A or 377A automated DNA sequencer (ABI, Foster City, CA) using a Taq fluorescent dideoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (ABI). Sequencing primers were as reported.33 Comparison to reported Ig germline sequences from GenBank and EMBL was performed using the Genetic Computer Group (GCG) sequence analysis program.

Confocal Laser-Scanning Microscopy Analysis of Human Cells and Tissue Biopsies

Human salivary gland (HSG) cells were grown in minimum essential medium, Eagle’s, in Earle’s balanced salt solution (EMEM) medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and allowed to adhere to chambered coverslips (Nunc, Kamstrup, Denmark) for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2, to form monolayers. Apoptosis of HSG cells was induced by incubating the cells with 100 ng/ml of tumor necrosis factor-α (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) and 1 μg/ml of cycloheximide for 3 to 15 hours at 37°C/5% CO2. Untreated cells or those induced to undergo apoptosis were fixed by 96% ice-cold ethanol for 5 minutes at 4°C or by 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were washed in PBS before being permeabilized in 0.005% saponin for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing in PBS and blocking with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour, cells were incubated with Ab. Fresh-frozen tissue was obtained from labial biopsies of patients with active SS and healthy controls. Freshly cut 5-μm sections were dried overnight, fixed by ice-cold 96% ethanol for 5 minutes at 4°C or by acetone for 10 minutes at room temperature, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum. HSG cells and tissue sections were incubated with human Fabs (10 μg/ml in PBS), or mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 (Affiniti) for 1 hour. In some experiments apoptotic cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC (Pharmingen, La Jolla, CA) for 1 hour before fixation. The slides were washed with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled (Fab′)2 goat anti-human IgG (Fab′)2 Ab (Jackson), and Texas Red-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (Jackson), or propidium iodine (Sigma) for 1 hour. The slides were again washed with PBS for 5 minutes and mounted with Slow Fade in PBS/glycerol (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) before analysis using a Zeiss Axiovert S100 TV confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss, New York, NY). All incubations were performed at room temperature unless otherwise indicated. As controls, all experiments were performed using the human Fab b12 to HIV-1 gp120 or by omitting the primary Ab. Adjacent tissue sections were hematoxylin and eosin stained or stained with anti-CD3 (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), and anti-cytokeratin 18 (CY-90; Sigma-Aldrich) mAbs to determine the cell type present.

Results

Serological Analysis of α-Fodrin Autoantibodies in SS Patients

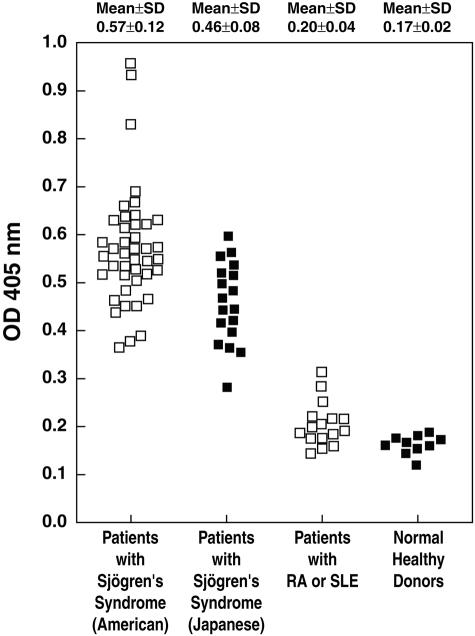

To investigate the specificity and sensitivity of anti-α-fodrin Abs for SS, serum from patients with SS, RA, SLE, and healthy individuals were tested for binding to mouse brain α-fodrin by ELISA. A secondary Ab capable of detecting both IgG and IgA was used, because anti-α-fodrin Ab of both the IgG and IgA have been suggested to be elevated in SS sera. As shown in Figure 1, elevated α-fodrin Ab levels were observed in both American and Japanese SS patients compared to the RA and SLE patient groups and healthy individuals. Positivity was defined as an OD405 value greater than twice the mean of the normal controls (>0.33) at a serum dilution of 1:400. Sera from all of the American SS patients and all but one of the Japanese SS patients were positive for α-fodrin Abs (98%), whereas only 1 of 16 RA/SLE patients (6%), and none of the healthy donors, were positive. The mean level of anti-α-fodrin Ab in both the American (OD405 nm, 0.57 ± 0.12) and Japanese SS patients (OD405 nm, 0.46 ± 0.08) were significantly higher than healthy controls (0.17 ± 0.02, P < 0.0001) or the RA/SLE patients (0.20 ± 0.04, P < 0.0001). The mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 was included in each experiment as a control (OD405 nm, 0.8).

Figure 1.

Sera from SS patients contain anti-α-fodrin Abs, as measured by ELISA. Sera, diluted 1:400 in PBS, from 42 American SS patients, 17 Japanese SS patients, 16 RA and SLE patients, and 10 healthy individuals were tested for binding to mouse brain α-fodrin by ELISA. Samples with A405 values more than twice the mean of the control normals (>0.33) were considered positive.

The frequency of SS sera with Abs specific for the 120-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin was determined by assessing binding to Western blots of mouse brain α-fodrin. Fifteen of 42 American SS sera (36%) (diluted 1:1000) exhibited reactivity against the 120-kd fragment of α-fodrin (Table 1). In addition, 10 sera showed reactivity with a 150-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin (24%), while 7 showed reactivity with a 180-kd fragment and other cleaved products of α-fodrin. As shown in Table 1, some patient sera reacted with multiple α-fodrin fragments, whereas the Western blot for other sera revealed reactivity with only one of the fragments. Overall, 22 American SS sera (52%) reacted with at least one form of cleaved α-fodrin. When the 17 Japanese SS sera were tested by Western blotting, the prevalence of anti-α-fodrin Ab reactivity was found to be significantly higher than in the American SS sera (12 of 17 positive, 70.6%; P < 0.01). All of the α-fodrin-reactive sera from the Japanese patients recognized 120-kd, but five also bound to the 150-kd α-fodrin (29.4%) (Table 1). Serum of 8 RA patients, 8 SLE patients, and 10 healthy individuals was also tested by Western blot analysis. Only one SLE serum was found to react with the 120-kd fragments of α-fodrin and none reacted with the 150-kd fragments of α-fodrin.

Table 1.

Binding of American (ASSP) and Japanese (JSSP) SS Patient Sera to Cleaved Mouse Brain α-Fodrin by Western Blot Analysis

| Patient | Intensity* of bands | Fragment size (kd) |

|---|---|---|

| ASSP1 | − | |

| ASSP2 | − | |

| ASSP3 | 1+ | 150 |

| ASSP4 | − | |

| ASSP5 | − | |

| ASSP6 | 1+ | 120 |

| ASSP7 | 3+ | 180 |

| ASSP8 | 3+ | 120, 150, 50 |

| ASSP9 | 2+ | 120 |

| ASSP10 | − | |

| ASSP11 | − | |

| ASSP12 | 1+ | 150, 80, 30 |

| ASSP13 | − | |

| ASSP14 | − | |

| ASSP15 | − | |

| ASSP16 | − | |

| ASSP17 | − | |

| ASSP18 | − | |

| ASSP19 | 1+ | 120, 150 |

| ASSP20 | 1+ | 120, 150 |

| ASSP21 | − | |

| ASSP22 | 2+ | 150, 180 |

| ASSP23 | 4+ | 120, 150 |

| ASSP24 | − | |

| ASSP25 | 2+ | 150 |

| ASSP26 | − | |

| ASSP27 | 2+ | 150 |

| ASSP28 | 3+ | 120, 180 |

| ASSP29 | 2+ | 120, 180 |

| ASSP30 | 5+ | 150 |

| ASSP31 | 3+ | 120 |

| ASSP32 | − | |

| ASSP33 | − | |

| ASSP34 | 3+ | 120 |

| ASSP35 | 2+ | 120, 180, 50 |

| ASSP36 | 1+ | 120 |

| ASSP37 | − | |

| ASSP38 | − | |

| ASSP39 | 1+ | 120, 180, 50 |

| ASSP40 | − | |

| ASSP41 | 2+ | 120, 180, 80 |

| ASSP42 | 2+ | 120, 50 |

| JSSP1 | 3+ | 120 |

| JSSP2 | 2+ | 120 |

| JSSP3 | 2+ | 120, 150 |

| JSSP4 | 2+ | 120 |

| JSSP5 | 2+ | 120, 150 |

| JSSP6 | 1+ | 120 |

| JSSP7 | 1+ | 120, 150 |

| JSSP8 | 1+ | 120 |

| JSSP9 | 1+ | 120 |

| JSSP10 | 1+ | 120, 150 |

| JSSP11 | 1+ | 120 |

| JSSP12 | 1+ | 120, 150 |

| JSSP13 | − | |

| JSSP14 | − | |

| JSSP15 | − | |

| JSSP16 | − | |

| JSSP17 | − |

The intensity was evaluated at a scale 1 to 5; 5 being the most intense.

Isolation of Human IgG mAbs Against the 150-kd Form of Cleaved α-Fodrin from SS Patients

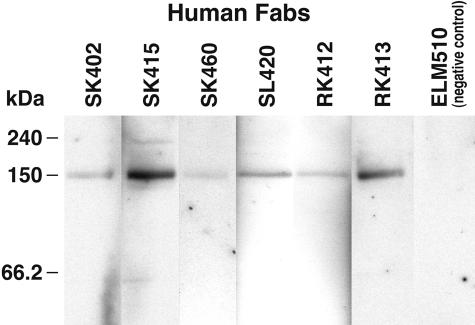

To characterize the anti-150-kd α-fodrin Abs response at a molecular level, IgG1 κ/λ Ab phage display libraries were generated from two patients (SS23 and SS30), whose sera predominantly recognized the 150-kd cleavage fragment of α-fodrin and also reacted with extract of human SS salivary gland tissue. As starting material for the Ab library construction, bone marrow was obtained from patients SS23 and SS30. Bone marrow has been shown to be a major repository for the plasma cells that produce the Abs found in the circulation. The Ab libraries from patients SS23 (≈6 × 106 members) and SS30 (≈8 × 106 members) were panned against mouse brain α-fodrin consisting of mostly intact α-fodrin, but also a small amount of apoptotic cleaved α-fodrin. The α-fodrin preparation was either separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane or coated on microtiter wells. After four rounds of biopanning against α-fodrin blotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, a significant increase in eluted phage was observed, indicating enrichment for antigen-binding Fab-phages. Individual clones, expressed as soluble Fabs by excising the gene III from the pcomb3 phagemid DNA from the last round of selection, were tested for binding to α-fodrin by Western blotting. This analysis yielded 19 Fabs that exhibited strong binding to the 150-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin and no binding to intact α-fodrin (240 kd), although present in significant excess, or the 120-kd cleaved form of α-fodrin (Figure 2). The Fabs also failed to react with Western blots of HeLa lysate, which contained intact α-fodrin, but not 120- or 150-kd α-fodrin, as determined by staining with mouse mAb AA6. Sequencing the DNA encoding the heavy chain variable region of the 19 Fabs revealed that 4 Fabs isolated from patient SS23 (SK402, SK415, SK460, and SL420) and 2 Fabs isolated from patient SS30 (RK412 and RK413) were unique, whereas the remaining sequences were repeats of the six sequences (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Binding of human monoclonal IgG Fabs to purified mouse α-fodrin brain extract by Western blot analysis. All of the Fabs specifically bound to the 150-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin and did not react with 240-kd intact α-fodrin. The human monoclonal anti-Ebola virus Fab ELZ510 was used as a negative control.

Table 2.

Deduced Amino Acid Sequences of the Heavy Chain CDR3 Region and Adjacent Framework Regions of Anti-150 kd, α-Fodrin IgGs

| Fab | VH/germline | FR3 | CDR3 | FR4 | JH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK402 (3) | VH1–8 | YYCAR | EGWPPTNDY | WGQ | JH4 |

| SK415 (1) | VH3–21 | YFCVR | DLCGGRDS | WGQ | JH5 |

| SK460 (2) | VH3–33 | YLCAR | EAWHDIGEYDGRRTLGSVPSLDL | WGQ | JH5 |

| SL420 (1) | VH3–21 | YYCAR | DGDGYRDY | WGQ | JH4 |

| RK412 (8) | VH1–69 | YYCAR | GFGGEDAYYDNFGYYASTEF | WGL | JH3 |

| RK413 (4) | VH4–4 | YYCAR | WGPRDLSGRSGGFDP | WGP | JH4 |

Number in parentheses denotes the number of Fabs that had the same heavy-chain CDR3 sequence. The closest germline gene, VH and JH families for each clone are also shown.

The IgG-Derived Anti-150-kd α-Fodrin Fabs Are Derived as a Result of an Affinity-Matured Antigen-Driven Antibody Response

Next, the variable heavy and light chain genes of the IgG-derived anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fab fragments were compared with the closest germline sequences in the GenBank database (Table 2). The Ab heavy chain is the major contributor to antigen-binding in many instances and so detailed analysis was focused on this chain. All of the variable heavy chain region genes of the anti-150-kd α-fodrin IgG Fabs were highly mutated, and exhibited a high replacement (R) to silent (S) mutation ratio (R/S ratio) for the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) (CDR1 and CDR2) compared to the framework regions (FR) (FR1, FR2, and FR3), characteristic of an affinity-matured antigen-driven Ab response. No particular restriction in the VH or JH gene usage of the anti-150-kd α-fodrin IgG Fabs was observed (Table 2), neither did the analysis reveal any restriction in the germline usage within the context of the VH families used. Unequivocal identification of the closest germline D segment proved impossible because of significant somatic modification.

Epitope Characterization

To pinpoint the epitopes recognized by the anti-150-kd α-fodrin human Fabs, three polypeptides spanning α-fodrin were coated on ELISA wells and tested for reactivity with the Fabs. The polypeptides included JS-1 (1 to 1784 bp), 2.7A (2258 to 4884 bp), and 3′DA (3963 to 7083 bp). None of the tested Fabs recognized any of the peptides, suggesting that the Fabs either recognized regions or partial conformational epitopes of α-fodrin not represented by the peptides.

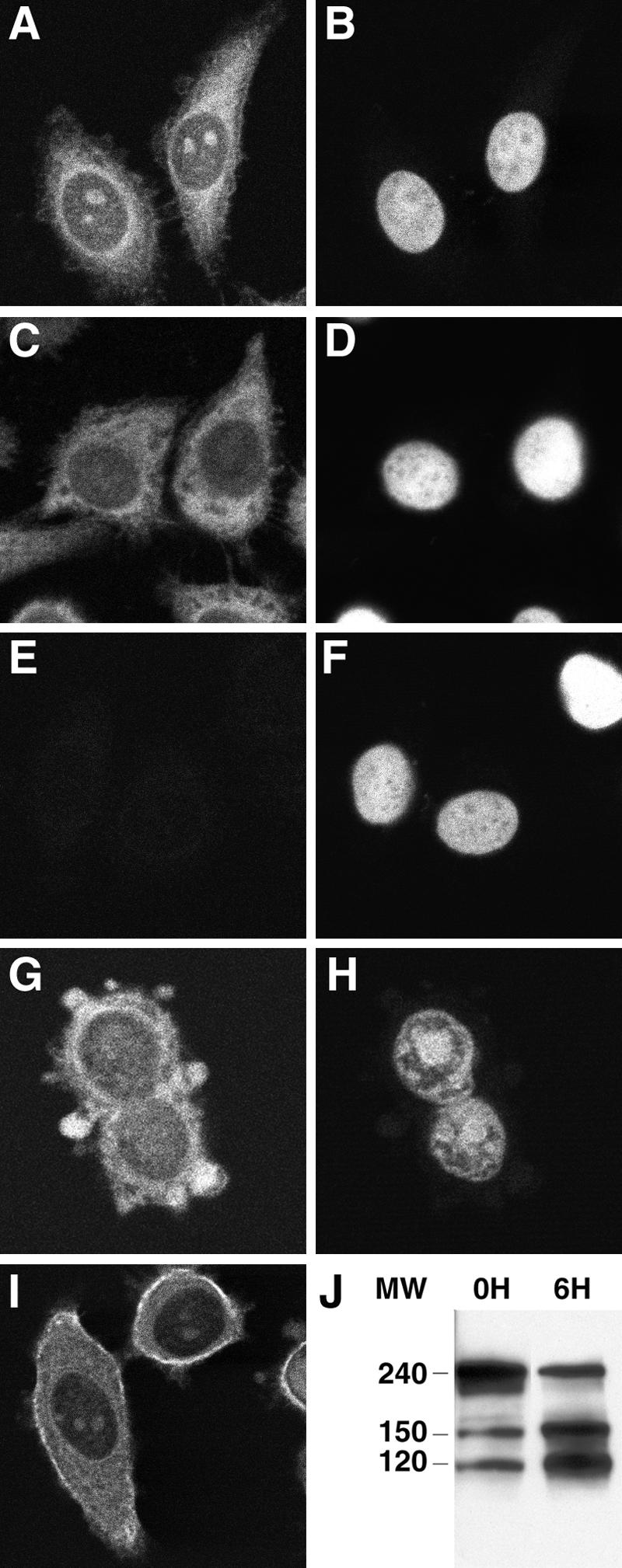

Subcellular Distribution of 150-kd α-Fodrin in HSG Cells

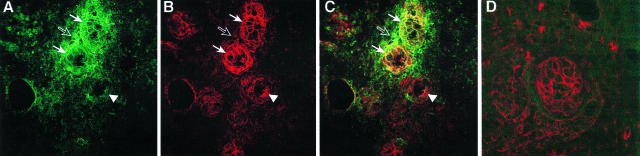

To determine the subcellular distribution of the 150-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin, HSG cells were stained with selected human Fabs and examined by laser-scanning confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 3, Fab SK415 and SK460 exhibited cytoplasmic staining, whereas no staining was observed with a control Fab. Similar cytoplasmic staining was also observed with mouse mAb AA6 recognizing both intact and cleaved α-fodrin (Figure 3I). As previously reported, the cytoplasmic staining of the mouse mAb AA6 was particularly intense, corresponding to the plasma membrane, but this was not observed with the human anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fabs. The fixation method of the HSG cells (ethanol or paraformaldehyde/saponin) did not seem to influence the staining patterns of Fab SK415 and mAb AA6.

Figure 3.

Subcellular distribution of intact and cleaved α-fodrin in human salivary cells. Ethanol-fixed human salivary HSG cells were stained with the human anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fabs SK415 (A) and SK460 (C), a human anti-HIV-1 gp120 Fab, b12 (E, negative control), and the mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 (I). Intense cytoplasmic staining with Fabs SK415 and SK460 and mouse mAb AA6 was observed in the permeabilized cells, although only partial co-localization between the human and mouse mAbs was observed. The cells were also stained with propidium iodine (B, D, F, H). Apoptotic HSG cells, exhibiting increased levels of cleaved 120- and 150-kd α-fodrin (J, 6H) compared to nonapoptotic cells (J, 0H), were also stained with Fab SK415 (G) and showed intense staining at the surface blebs.

Cleaved 150-kd α-Fodrin Is Present in Blebs of Apoptotic HSG Cells

Previous studies have shown that α-fodrin is cleaved by different apoptotic enzymes, but the question remained as to how α-fodrin, an intracellular protein, became exposed to the immune system. One possibility is that 150-kd fragments of α-fodrin are exposed on the cell surface during the morphological and biochemical process of apoptosis. Recent reports have demonstrated that certain SS-associated autoantigens, including La, translocate during apoptosis to the cell surface, and particularly to cell surface blebs.34–36 To determine whether 150-kd α-fodrin fragments become concentrated at the surface of apoptotic HSG cells, apoptosis was induced in HSG cell cultures by tumor necrosis factor-α and cycloheximide, and the cells stained with the anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fab SK415 or anti-HIV-1 gp120 Fab (negative control), and propidium iodine (PI). Apoptotic cells were visualized by the binding of fluorescein isothiocyanate-annexin V to phosphatidylserine on the cell surface before fixation and by morphological appearance, including nuclear condensation, surface blebbing, and cell shrinkage (Figure 3, G and H). HSG cell cultures induced by tumor necrosis factor-α and cycloheximide to undergo apoptosis were also analyzed by Western blot and showed increased levels of cleaved 120- and 150-kd α-fodrin (Figure 3J, 6H) compared to noninduced HSG cell cultures, which contained only low amounts of constitutive apoptotic cells, as previously reported (Figure 3J, 0H).14,17 Confocal analysis demonstrated that anti-150-kd α-fodrin translocated to cell surface blebs of apoptotic HSG cells (Figure 3G). No staining was observed with a control human Fab Ab against HIV-1 gp120 (data not shown).

Localization of 150-kd Cleaved α-Fodrin within SS Salivary Gland Tissue

To determine the distribution of 150-kd fragments of α-fodrin in salivary tissue from patients with active SS, fresh-frozen labial biopsies from three SS patients were obtained and examined by immunohistochemistry. Cryostat tissue sections were stained with anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fab SK415 and a mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 (Figure 4, A and B). Laser-scanning confocal microscopy of the SS-infiltrated salivary gland using SK415 revealed intense staining of the acinar epithelia cells, with intensification at the cell surface and co-localization with the mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb (Figure 4C, solid arrows). However, SK415 also exhibited intense patchy staining corresponding to the lymphocytic infiltrate immediately surrounding the affected acini, an area not stained by the mAb AA6 or the fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-human F(ab′)2 Ab alone (Figure 4, open arrows). The SK415 staining in this area was not confined to cells, but seemed to be associated with 150-kd α-fodrin, which had leaked from inflamed glandular cells. The unaffected duct cells were stained by mAb AA6 (Figure 4, arrowheads), but only weakly by Fab SK415. Similarly, duct cells from normal salivary gland tissue were stained by mAb AA6, but not, or only weakly, by Fab SK415 (Figure 4D). The fixation method of the labial biopsy sections (ethanol or acetone) did not seem to influence the staining patterns of Fab SK415 and mAb AA6.

Figure 4.

Distribution of cleaved and intact α-fodrin in salivary gland tissue of a SS patient with active disease. Tissue sections from salivary gland biopsies of patients with SS were stained with human anti-150-kd α-fodrin Fab SK415 (A, green) and mouse anti-α-fodrin mAb AA6 (B, red) and analyzed by laser-scanning confocal microscopy. Intense staining corresponding to acinar epithelia cells, and with intensification at the cell surface was observed with SK415 (solid arrows). Only partial co-localization was observed between Fab SK415 and mAb AA6 (C), because Fab SK415, but not mAb AA6, also stained areas corresponding to the lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the affected acini (open arrow), whereas AA6, but not SK415, stained unaffected ducts (arrowhead). Duct cells from a normal salivary gland were stained with AA6, but not, or only weakly, with SK415 (D). No staining of the salivary gland tissue sections was observed with the negative control Fab b12 or a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-human F(ab)2 alone (not shown).

Discussion

Lymphocyte infiltration in the salivary glands leading to glandular destruction is a common finding in SS patients. The infiltrate consists of predominantly T cells as well as large numbers of B and plasma cells that actively produce immunoglobulin with autoimmune reactivity. To elucidate the components of this immunopathology, we examined the Ab response to α-fodrin in SS patients using serology and phage display cloning.

In the initial study proposing anti-α-fodrin Abs as a disease marker of SS, Western blot analysis of a large panel of Japanese SS patients showed that IgG Ab to 120-kd cleaved α-fodrin could be used as a marker for SS, because it exhibited high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (100%).7 Subsequently, anti-120-kd α-fodrin Abs were also found in some patients with SLE without SS.9 The high sensitivity and specificity of anti-α-fodrin Ab as a diagnostic marker of SS has been questioned,21 although other investigators have also found good correlation between SS and anti-α-fodrin Abs, although the sensitivity was lower than in the Japanese study.11,37 We investigated a panel of SS patients fulfilling the strict San Diego criteria by evaluating serum panels by both ELISA and Western blotting using purified mouse brain α-fodrin, similar to the antigen source used in the initial Japanese study. This antigen preparation contains both intact (240 kd) and cleaved forms (eg, 120 kd, 150 kd) of α-fodrin, and thus will also be recognized by Abs that specifically bind epitopes accessible only on the cleaved forms of α-fodrin, such as those cloned in this study. Our study demonstrated significant differences in sensitivity between ELISA and Western blotting, suggesting that a major part of the α-fodrin Ab response is directed against conformational epitopes, or that the affinity of the anti-α-fodrin Ab in some SS patients was not sufficient to allow detection by Western blotting. Nearly all (98%) of the SS patients were positive for α-fodrin by ELISA, whereas anti-α-fodrin Ab reactivity by Western blotting was significantly lower (52%), and only 36.0% stained the 120-kd α-fodrin fragment. Some differences in α-fodrin Ab profiles were observed between the American and the Japanese SS patient groups, probably because the two groups represent two distinct populations with different genetic and environmental influences.

Interestingly, we found that ∼25% of both the American and Japanese SS sera recognized a 150-kd fragment of cleaved α-fodrin, an Ab specificity not previously evaluated. This specificity was not seen in a panel of sera from healthy individuals and patients with SLE or RA. Molecular analysis of the anti-150-kd Ab response using IgG Ab phage display libraries generated from two of anti-150-kd seropositive SS patients yielded a panel of hmAbs that specifically recognized the 150-kd form of cleaved α-fodrin and not 120-kd or intact α-fodrin. The specificity of these hmAbs is distinct from that of the currently available mouse anti-α-fodrin mAbs recognizing 150-kd α-fodrin, which also bind 120-kd α-fodrin and intact α-fodrin.

In the NFS/sld SS mouse model, dysregulation of anti-fodrin CD4+ T cells leads to Fas-mediated apoptosis of salivary gland epithelial cells and a corresponding increase in clinical symptoms.8 In humans, a similar scenario has been proposed, and increased apoptosis has been observed in SS salivary glands. Fas expression in the salivary gland cells and FasL on the infiltrating CD4+ T cell in SS patients have been reported, although their roles in disease pathology remain to be elucidated.38 In addition, CTL-mediated lysis/apoptosis though the granzyme and perforin pathways may be involved in salivary gland destruction.2 In the mouse model,8 the increased apoptosis was accompanied by an increase in cleaved 120-kd α-fodrin in the affected tissue, as well as in serum anti-120-kd Ab levels, similar to our observation of cleaved 150-kd α-fodrin in SS patients. Indeed, treatment of mice with caspase inhibitors prevented induction of SS,19 suggesting that α-fodrin cleavage and anti-α-fodrin Ab production is more that an epiphenomenon. We found the 150-kd α-fodrin fragment within affected acinar epithelial cells, and also in the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate. In the latter areas, the staining was not confined to cells, suggesting leakage of the 150-kd α-fodrin fragment from the apoptotic acinar/ductal epithelial cells into the surrounding interstitium. Interestingly, leakage of 150-kd fragments of α-fodrin has also been observed in tissue cultures of apoptotic human neuroblastoma cells.39 In contrast, the anti-150-kd Fabs stained normal salivary cells with lower intensity than a mouse mAb recognizing both intact and cleaved α-fodrin. Our observation seems to support earlier findings that low levels of 120-kd and 150-kd are present in normal cells, but are significantly increased during apoptosis.14 Our study also suggests that 150-kd α-fodrin is translocated to cell surface blebs in apoptotic HSG cells, similar to Ro/SSA,35,36 thereby possibly presenting it to the immune system and eliciting an Ab response. Previous studies have shown α-fodrin to be cleaved by calpain in apoptotic T cells, and by calpain and caspases in anti-Fas-stimulated Jurkat cells and/or neuronal apoptosis.15–17 In human SS, the 150-kd α-fodrin fragments are most likely the result of caspase cleavage,18,19 but this requires further analysis. In addition, α-fodrin can be cleaved by an unidentified protease present in granules of CD8+ CTLs.18 Interestingly, membrane blebbing during apoptosis has been suggested to be partially due to fodrin cleavage.14

In conclusion, our data supports the theory that in SS patients, α-fodrin is cleaved during apoptosis in the inflamed salivary gland tissue and elicits an Ab response to the cleaved products. Our study also showed that the Ab response to α-fodrin in SS patients is not limited to Abs against the 120-kd fragment, but includes other cleaved products, such as the 150-kd fragment. Inclusion of these Ab specificities would likely increase the sensitivity of the anti-α-fodrin Ab test, and enhance its usefulness as a diagnostic marker of human SS. The isolated human monoclonal Abs to cleaved α-fodrin may serve as useful reagents for diagnostic immunohistochemical analysis of SS salivary gland tissue and study of SS pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Henrik J. Ditzel, Center of Medical Biotechnology, University of Southern Denmark, Winsloewparken 25, 3, 5000 Odense C, Denmark. E-mail: hditzel@health.sdu.dk.

Supported in part by a research grant from the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI41590 and HL63651 to H.J.D.).

References

- Fox RI, Tornwall J, Maruyama T, Stern M. Evolving concepts of diagnosis, pathogenesis, and therapy of Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1998;10:446–456. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapinos NI, Polihronis M, Tzioufas AG, Skopouli FN. Immunopathology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Med Interne (Paris) 1998;149:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson R, Moen K, Vestrheim D, Szodoray P. Current issues in Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. 2002;8:130–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation,; Sjögren’s SyndromePrimer on the Rheumatic Diseases. 1998:pp 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Moutsopoulos HM, Balestrieri G, Bencivelli W, Bernstein RM, Bjerrum KB, Braga S, Coll J, de Vita S. Preliminary criteria for the classification of Sjogren’s syndrome. Results of a prospective concerted action supported by the European Community. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:340–347. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Moutsopoulos HM, Coll J, Gerli R, Hatron PY, Kater L, Konttinen YT, Manthorpe R, Meyer O, Mosca M, Ostuni P, Pellerito RA, Pennec Y, Porter SR, Richards A, Sauvezie B, Schiodt M, Sciuto M, Shoenfeld Y, Skopouli FN, Smolen JS, Soromenho F, Tishler M, Wattiaux MJ. Assessment of the European classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome in a series of clinically defined cases: results of a prospective multicentre study. The European Study Group on Diagnostic Criteria for Sjogren’s Syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55:116–121. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haneji N, Nakamura T, Takio K, Yanagi K, Higashiyama H, Saito I, Noji S, Sugino H, Hayashi Y. Identification of alpha-fodrin as a candidate autoantigen in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Science. 1997;276:604–607. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru N, Saegusa K, Yanagi K, Haneji N, Saito I, Hayashi Y. Estrogen deficiency accelerates autoimmune exocrinopathy in murine Sjogren’s syndrome through Fas-mediated apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:173–181. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65111-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Tsuchida T, Kanda N, Mori K, Hayashi Y, Tamaki K. Anti-alpha-fodrin antibodies in Sjogren syndrome and lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:535–539. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa S, Yanagi K, Yoshioka A, Kidoguchi K, Shirai T, Hayashi Y. Neonatal lupus erythematosus: maternal IgG antibodies bind to a recombinant NH2-terminal fusion protein encoded by human alpha-fodrin cDNA. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1189–1192. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte T, Matthias T, Oppermann M, Helmke K, Peter HH, Schmidt RE, Tishler M. Prevalence of antibodies against alpha-fodrin in Sjogren’s syndrome: comparison of 2 sets of classification criteria. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2157–2159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin D, Aunis D. Reorganization of alpha-fodrin induced by stimulation in secretory cells. Nature. 1985;315:589–592. doi: 10.1038/315589a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leto TL, Pleasic S, Forget BG, Benz EJ, Jr, Marchesi VT. Characterization of the calmodulin-binding site of nonerythroid alpha-spectrin. Recombinant protein and model peptide studies. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5826–5830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SJ, O’Brien GA, Nishioka WK, McGahon AJ, Mahboubi A, Saido TC, Green DR. Proteolysis of fodrin (non-erythroid spectrin) during apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6425–6428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SJ, Finucane DM, Amarante-Mendes GP, O’Brien GA, Green DR. Phosphatidylserine externalization during CD95-induced apoptosis of cells and cytoplasts requires ICE/CED-3 protease activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28753–28756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanags DM, Porn-Ares MI, Coppola S, Burgess DH, Orrenius S. Protease involvement in fodrin cleavage and phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31075–31085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath R, Raser KJ, Stafford D, Hajimohammadreza I, Posner A, Allen H, Talanian RV, Yuen P, Gilbertsen RB, Wang KK. Non-erythroid alpha-spectrin breakdown by calpain and interleukin 1 beta-converting-enzyme-like protease(s) in apoptotic cells: contributory roles of both protease families in neuronal apoptosis. Biochem J. 1996;319:683–690. doi: 10.1042/bj3190683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju K, Cox A, Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A. Novel fragments of the Sjogren’s syndrome autoantigens alpha-fodrin and type 3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor generated during cytotoxic lymphocyte granule-induced cell death. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2376–2386. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200110)44:10<2376::aid-art402>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa K, Ishimaru N, Yanagi K, Mishima K, Arakaki R, Suda T, Saito I, Hayashi Y. Prevention and induction of autoimmune exocrinopathy is dependent on pathogenic autoantigen cleavage in murine Sjogren’s syndrome. J Immunol. 2002;169:1050–1057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeno N, Takei S, Imanaka H, Oda H, Yanagi K, Hayashi Y, Miyata K. Anti-alpha-fodrin antibodies in Sjogren’s syndrome in children. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:860–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte T, Matthias T, Arnett FC, Peter HH, Hartung K, Sachse C, Wigand R, Braner A, Kalden JR, Lakomek HJ, Schmidt RE. IgA and IgG autoantibodies against alpha-fodrin as markers for Sjogren’s syndrome. Systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2617–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi K, Ishimaru N, Haneji N, Saegusa K, Saito I, Hayashi Y. Anti-120-kDa alpha-fodrin immune response with Th1-cytokine profile in the NOD mouse model of Sjogren’s syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3336–3345. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3336::AID-IMMU3336>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI, Saito I. Criteria for diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20:391–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney R, Levine J, Willard M. Purification of fodrin from mammalian brain. Methods Enzymol. 1986;134:42–54. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)34074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicke RU, Ng P, Sprengart ML, Porter AG. Caspase-3 is required for alpha-fodrin cleavage but dispensable for cleavage of other death substrates in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15540–15545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson MA, Caothien RH, Burton DR. Generation of diverse high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies by repertoire cloning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2432–2436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas CF, III, Wagner J. Synthetic human antibodies selecting and evolving functional protein. Methods CTMIE. 1995;8:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Barbas CF, III, Persson MA, Koenig S, Chanock RM, Lerner RA. A large array of human monoclonal antibodies to type 1 human immunodeficiency virus from combinatorial libraries of asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10134–10137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Rodriguez LL, Jahrling PB, Sanchez A, Khan AS, Nichol ST, Peters CJ, Parren PW, Burton DR. Ebola virus can be effectively neutralized by antibody produced in natural human infection. J Virol. 1999;73:6024–6030. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6024-6030.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmerdam PA, van den Herik-Oudijk IE, Parren PW, Westerdaal NA, van de Winkel JG, Capel PJ. Interaction of a human Fc gamma RIIb1 (CD32) isoform with murine and human IgG subclasses. Int Immunol. 1993;5:239–247. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzel HJ, Binley JM, Moore JP, Sodroski J, Sullivan N, Sawyer LS, Hendry RM, Yang WP, Barbas CF, III, Burton DR. Neutralizing recombinant human antibodies to a conformational V2- and CD4-binding site-sensitive epitope of HIV-1 gp120 isolated by using an epitope-masking procedure. J Immunol. 1995;154:893–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binley JM, Ditzel HJ, Barbas CF, III, Sullivan N, Sodroski J, Parren PW, Burton DR. Human antibody responses to HIV type 1 glycoprotein 41 cloned in phage display libraries suggest three major epitopes are recognized and give evidence for conserved antibody motifs in antigen binding. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1996;12:911–924. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciola-Rosen LA, Anhalt G, Rosen A. Autoantigens targeted in systemic lupus erythematosus are clustered in two populations of surface structures on apoptotic keratinocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1317–1330. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baboonian C, Venables PJ, Booth J, Williams DG, Roffe LM, Maini RN. Virus infection induces redistribution and membrane localization of the nuclear antigen La (SS-B): a possible mechanism for autoimmunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;78:454–459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann M, Chang S, Slor H, Kukulies J, Muller WE. Shuttling of the autoantigen La between nucleus and cell surface after UV irradiation of human keratinocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1990;191:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90002-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandbelt M, Degen W, van de Putte L, van Venrooij W, van den Hoogen Nijmegen F. Anti-a-fodrin antibodies: not specific nor sensitive for Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(Abstract 428 Suppl):S142. [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Ogawa N, Nakabayashi T, Liu GT, D’Souza E, McGuff HS, Guerrero D, Talal N, Dang H. Fas and Fas ligand expression in the salivary glands of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:87–97. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Chiu YC, Probert AW, Wang KK. Selective release of calpain produced alphalI-spectrin (alpha-fodrin) breakdown products by acute neuronal cell death. Biol Chem. 2002;383:785–791. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]