Abstract

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a neoplasm of bone characterized by a localized osteolytic lesion. The nature of GCT is an enigma and the cell type(s) and protease(s) responsible for the extensive localized clinicoradiological osteolysis remain unresolved. We evaluated protease expression and cellular distribution of the proteolytic machinery responsible for the osteolysis. mRNA profiles showed that cathepsin K, cathepsin L, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 were the preferentially expressed collagenases. Moderate expression was found for MMP-13, MMP-14, and cathepsin S. Specific protease activity assays revealed high cathepsin K activity but showed that MMP-9 was primarily present (98%) as inactive proenzyme. Activities of MMP-13 and MMP-14 were low. Immunohistochemistry revealed a clear spatial distribution: cathepsin K, its associated proton pump V-H+-ATPase, and MMP-9 were exclusively expressed in osteoclast-like giant cells, whereas cathepsin L expression was confined to mononuclear cells. To explore a possible role of cathepsin L in osteolysis, GCT-derived, cathepsin L-expressing, mononuclear cells were cultured on dentine disks. No evidence of osteolysis by these cells was found. These results implicate cathepsin K as the principal protease in GCT and suggest that osteoclast-like giant cells are responsible for the osteolysis. Inhibition of cathepsin K or its associated proton-pump may provide new therapeutic opportunities for GCT.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a benign neoplasm of bone, clinically characterized by a solitary localized metaphyseal osteolytic lesion.1,2 GCT typically occurs in the epiphyseal remnant section of long tubular bones of young adults. Less common but well-documented sites of involvement include sacrum (5%), pelvis, and spine. Curettage and adjunctive nonspecific cytotoxic treatment of the surgical margins followed by bone grafting has reduced local recurrence rate to 10 to 35%3 but final prognosis is highly dependent on localization of the process.1–3

The nature of GCT remains an enigma: the process is hallmarked by a localized osteolytic process but local aggressiveness is not exclusively limited to bone tissue, and soft tissue and vascular infiltration is a common finding in GCT.1–3 So called “benign pulmonary metastases” are found in 1 to 2% of all cases and formation of metastasis appears unrelated to local aggressiveness. Histologically, the tumor is characterized by osteoclast-like giant cells in a background of round-shaped mononuclear cells and spindle-shaped stromal cells.1–3 In as much as the mononuclear cells represent the actual neoplastic component and whether the multinucleated osteoclast-like cells are responsible for the bone resorption is still a matter of debate.4,5

Bone is a highly stable fiber-reinforced, calcified tissue. Resorption of bone depends on the concord action of specific proteases able to remove the organic matrix (predominantly fibrillar type I collagen),6 and the formation of an acidic microenvironment necessary for solubilization of the inorganic mineral component (hydroxyapatite).7 A number of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), ie, gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), and stromelysin (MMP-3) have been implicated in the local aggressive behavior of GCT2 but it is dubious whether these proteases are directly responsible for the osteolysis. Fibrillar collagen is highly resistant to proteolytic degradation8 and the only mammalian proteases that have been shown to cleave the native triple helical region of fibrillar collagen are the collagenases of the MMP family9 (ie, MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13, and the membrane type-1 MMP (MT-1 MMP or MMP-14)10 and members of the cysteine protease family (ie, cathepsin L11 and cathepsin K8,12).

Cathepsin K is a unique and potent collagenase primarily expressed in osteoclasts. Cathepsin K is responsible for degradation of the collagen matrix in bone and the critical involvement of cathepsin K in bone remodeling is supported by the finding that cathepsin K deficiency causes the bone-sclerosing disorder pycnodysostosis,13 and by the ability of specific cathepsin K inhibitors to alleviate bone resorption in a primate model of hypogonadism.14 Whether cathepsin K is also responsible for osteolysis by GCT remains to be established.

To identify the culprit protease(s) in the GCT-mediated osteolysis we used an integrated approach: mRNA expression profiles of MMP and cysteine collagenases in GCTs were established by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and cellular distribution of candidate proteases was assessed by immunohistochemistry. Because these approaches do not provide information on the critical posttranscriptional regulation of protease activity,9 we therefore used specific immunocapture protease activity assays,15,16 and in vitro assays that address the complex posttranslational regulation of protease activity.

Materials and Methods

Patients

All samples were obtained during surgery and processed in a coded manner in accordance with the guidelines of the local medical ethical committee. Samples were split and snap-frozen in CO2-cooled isopentane or fixed in formaldehyde for histological analysis. Histological diagnosis was confirmed by an experienced pathologist (P.C.W.H.).

Real-Time Competitive LightCycler MMP and Cathepsin PCR

Real-time PCR was performed according to the Taqman method of Applied Biosystems (Nieuwerkerk aan de Ijssel, The Netherlands) by using a combination of a forward and a backward primer and a specific [6-carboxy-fluorescein/6-carboxy-tetramethyl-rhodamine (FAM/TAMRA)] double-labeled probe. Specific amplicons were chosen according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Results were corrected for glyceraldehyde-3- phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression. Protease probes and primers were obtained form Isogen (Maarsen, The Netherlands) and the VIC-labeled GAPDH primer-probe combination was purchased from Applied Biosystems (Nieuwerkerk aan de IJssel, The Netherlands).

Specific Immunocapture Activity Assays

MMP-9 and MMP-13 activity assays (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) were performed according to the suppliers recommendations. These assays measure both active (mature) MMP as well as total MMP [ie, already active plus activatable (latent or pro-MMP)] activity. In brief, MMP-9 or MMP-13 are captured by a specific antibody immobilized on a microtiter plate. Total (latent and active) MMP activity is measured through activation of the latent MMP by preincubation with 0.5 mmol/L p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) for 2 hours at 37°C. MMP activity is assessed by incubation of the captured MMP with a modified proenzyme (UKcol) and subsequent proteolytic activation of the UKcol was quantified using a chromogenic peptide substrate (S-2444). Color development was recorded at 405 nm at different time intervals.17

We developed a similar technique for the assessment of cathepsin K activity. Costar Stripwell plates were coated (2 hours, 4°C) with 100 μl of cathepsin K-specific monoclonal antibody (TNO B1446, 1 μg/ml) generated against a loop structure in the mature protein. This antibody recognizes native cathepsin K, does not cross-react with cathepsin L or cathepsin S; minimally cross-reacts with cathepsin V (less than 5%, Figure 1), and does not affect activity. Binding of cathepsin K was performed by incubation of purified cathepsin K or biological sample for 16 hours at 4°C in capture buffer [50 mmol/L sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 2.5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.03 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.01% (v/v) gelatin, and 0.01% (v/v) Tween-80], plates were subsequently washed four times with capture buffer and incubated with detection buffer [50 mmol/L sodium acetate, pH 6.5, 2.5 mmol/L EDTA, 0.03 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.01% (v/v) gelatin, and 0.01% (v/v) Tween-80]. Cathepsin K activity was measured by incubation of the captured cathepsin K with a modified prourokinase variant (UKcatK) in which the endogenous plasmin activation site has been adapted to a cathepsin K-specific activation site. Activated UKcatK was quantified using a chromogenic peptide substrate (S-2444; Biosource Europe, Nivelles, Belgium) and color development was recorded at 405 nm. Assay sensitivity is dependent on the incubation time and ranges from 0.04 to 3 ng/ml at a typical reaction time of 2 hours. Cross-reactivity of the assay with other cathepsin cysteine proteases is minimal (cross-reactivity for cathepsin L, cathepsin S, and cathepsin V: 0.02%, 0.01%, and 0.7%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Specificity of the cathepsin K-specific monoclonal antibody (TNO B1446) (Western blot analysis: lane 1, cathepsin K; lane 2, negative control buffer; lane 3, pro-MMP-3; lane 4, cathepsin L; lane 5, cathepsin S; and lane 6, cathepsin V), showing minimal cross-reactivity (∼5%) with cathepsin V and no cross reactivity with cathepsins L and S. MMP-3 was included as a negative control.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-μm deparaffinized, ethanol-dehydrated tissue sections. For cathepsin K, cathepsin L, and MMP-9 tissue sections were boiled for 10 minutes in 10 mmol/L citrate, pH 6.0, in a microwave oven, allowed to cool to room temperature and rinsed with PBS. Tissue sections were subsequently incubated overnight with a polyclonal antibody against cathepsin K (Santa Cruz. Heidelberg, Germany), cathepsin L (Chemicon Europe, Ltd., Chandlers Ford, UK), cathepsin S (a generous gift from Dr. E. Weber, Institute of Physiological Chemistry, Medical Faculty, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Germany), or MMP-9 (polyclonal, TNO B21).17 Staining for V-ATPase was performed by a polyclonal antibody against the 100-kd transmembrane subunit of the human V-ATPase (a generous gift from Dr. M.A. Harrison, School of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK). AB-conjugated biotinylated anti-goat or rabbit anti-IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Sections were stained with Nova Red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin. Controls were performed by omitting the primary antibody.

Collagen Degradation Assay

GCT homogenate and reconstituted fluorescein-labeled collagen (2 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich Chemie B.V. Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) were incubated in a sodium-acetate buffer (50 mmol/L), pH 5.5, containing 2.5 mmol/L EDTA, 0.3 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 0.01% Tween (cathepsin buffer) or in a Tris buffer (50 mmol/L), pH 7.6, containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2, 1 μmol/L ZnCl2, 0.01% Brij, and 150 mmol/L NaCl (MMP buffer). After incubation (16 hours, 36°C), mixtures were centrifuged and fluorescence of released labeled peptides quantified.18

Bone Degradation by Cathepsin L-Expressing GCT-Derived Mononuclear Cells

The ability of GCT-derived cathepsin L-expressing mononuclear cells to induce osteolysis was assessed by a bone degradation assay. Three mononuclear cell lines were derived from clinicoradiological distinct, histologically proven, primary GCTs (L980, L1050, L1180). Tissue samples were obtained during surgery, mechanically dissected, and cells separated by collagenase treatment. The cell suspension was subsequently cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (GIBCO). Depending on the cell growth and density, samples were refreshed in every 3 to 5 days and were propagated in new dishes on confluence. Giant cells gradually disappeared and were only seen in the first two passages. Detailed characteristics of the developed cell lines are provided by Szuhai and colleagues (submitted for publication).

The osteolytic potential of these mononuclear cells was tested in a bone degradation assay: to that end GCT-derived mononuclear cells at passage numbers 16,16, and 9 (L980, L1050, and L1180, respectively), were cultured individually for 1 to 21 days on devitalized dentine disks (IDS, Boldon, UK) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% (v/v) fetal calf serum (GIBCO). Medium was refreshed weekly according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 1, 3, 7, 14, or 21 days bone slices with cells were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 mol/L sodium cacodylate solution for 10 minutes at room temperature and stained with 1% (w/v) toluidine blue in 0.5% (w/v) sodium tetraborate solution for 3 minutes. Bone resorption was reviewed by light microscopy.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in protease activity were compared by the independent t-test.

Results

Clinical characteristics and origin of the tumor samples are shown in Table 1. GCT mRNA expression profiles of MMP and cathepsin collagenases are shown in Figure 2. Normalized Ct values for GCT mRNA expression are provided in Table 2. Cathepsin K and to a lesser extend cathepsin L and MMP-9 appeared the most abundantly expressed proteases in GCT. Expression of cathepsin S, cathepsin V, MMP-13, and MMP-14 was considerably lower whereas expression of MMP-1 and MMP-8 remained below the detection threshold of the assay (≥40 PCR cycles).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patient Population

| Age | Gender | Bone | Site | Grade | Prim/Rec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L35 | 34 | Female | Femur | Distal ME | 2 | Prim |

| L42 | 30 | Female | Femur | Distal ME | 2 | Rec |

| L48 | 52 | Female | Femur | Distal ME | 2 | Prim |

| L82 | 20 | Male | Radius | Distal ME | 2 | Prim |

| L806 | 42 | Male | Femur | Distal ME | 3 | Rec |

| L858 | 40 | Female | Vertebra | Sacral Corpus | 2 | Rec |

| L980* | 27 | Male | Femur | Distal ME | 2 | Prim |

| L1050† | 50 | Male | Tibia | Proximal ME | 2 | Prim |

| L1180† | 20 | Male | Femur | Distal ME | 2 | Prim |

ME, Meta-epiphysis; Prim, primary; Rec, recurrence.

Both primary tumor material and mononuclear cell line available.

Exclusively mononuclear cell line available.

Figure 2.

Normalized protease mRNA expression in human GCTs (GAPDH = 1) assessed by real-time PCR cycles presented on a log scale. Mean (SD) of seven individual tumors. ND, not detectable (>40 PCR cycles).

Table 2.

Normalized Delta Ct Values for MMP and Cathepsin Collagenases (GAPDH = 0)*

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| MMP-9 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| MMP-13 | 5.4 | 0.7 |

| MMP-14 | 10.8 | 1.6 |

| Cathepsin K | −1.1 | 1.3 |

| Cathepsin L | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Cathepsin S | 3.1 | 0.5 |

| Cathepsin V | 10.8 | 1.3 |

Expression of MMP-1 and -8 was below the detection threshold of the assay (more than 40 cycles).

Cellular distribution of the preferentially expressed proteases was assessed by immunohistochemistry, which revealed a distinct expression pattern: cathepsin K and MMP-9 (Figure 3, B and C) were exclusively expressed in the multinucleated giant cells whereas expression of cathepsins L and S was confined to the mononuclear cells (Figure 3, D and E). Cathepsin K stability and activity is highly pH-dependent and in osteoclasts an acidic microenvironment required for optimum cathepsin K activity and stability is created by the action of vacuolar ATPase, a trans-membranous proton pump. Figure 3F shows that the multinucleated giant cells express the proton pump V-H+-ATPase.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of human GCT. A: control; B: cathepsin K; C: MMP-9; D: cathepsin L; E: cathepsin S; and F: V-H+-ATPase. Note that cathepsin K, MMP-9, and v-ATPase are exclusively expressed in the multinucleated giant cells whereas cathepsin L and S expression is confined to the mononuclear cells. Arrows in A indicate the multinucleated giant cells. Original magnifications, ×200.

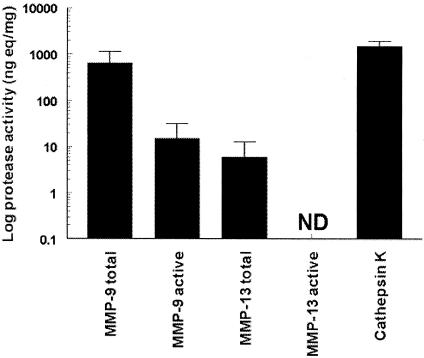

Results of the above studies do not address the complex regulation of protease activity. We therefore used specific immunocapture protease activity assays to quantify cathepsin K, MMP-9, and MMP-13 activities. Figure 4 shows that cathepsin K was by far the most abundant active protease (P < 0.001). High total activity was also found for MMP-9 but only a small fraction (∼2%) of the enzyme was present in the active form (P < 0.001), thus indicating that the enzyme is predominantly present as an inactive proenzyme (latent form). Total MMP-13 activity was low and active MMP-13 remained below the detection limit of the assay.

Figure 4.

Total (ie, latent and active) and active MMP-9, MMP-13, and cathepsin K activity in GCT [activity is expressed as recombinant enzyme equivalents (ng)/mg homogenate]. Mean (SD) of seven individual tumors. ND, not detectable.

Involvement of cathepsin and MMP collagenases was further explored through incubation of fluorescein-labeled fibrillar collagen in selective buffer systems: collagen degradation was not observed at pH 7.4 whereas substantial collagen destabilization was seen at pH 5.5 in the presence of EDTA (results not shown), thus indicating involvement of cathepsin rather than MMP collagenases.

The role of cathepsin L in bone resorption is far from clear. Cathepsin L is primarily expressed by mononuclear cells and not by the multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3). We have established several GCT-derived mononuclear cell lines that show ample cathepsin L, moderate cathepsin S, and low cathepsin K mRNA expression (Figure 5). To explore a possible direct role of cathepsin L in bone resorption, separate GCT-derived mononuclear cell lines were seeded and grown to confluence on devitalized dentine disks, a model of bone resorption. Growth of the mononuclear cell population on dentine disk was relatively slow and for the first 14-day culture period only a moderate cell proliferation was observed. After 21 days of culture all cell lines showed 75 to 95% confluence on the dentine disk. No evidence for osteolysis was found throughout the 21-day culture period (Figure 6). Formation of bi- or multinucleated cell was extremely rare, indicating formation of multinucleated tumor cells formed by endo-reduplication rather than existence of true giant cells.

Figure 5.

Relative mRNA expression (GAPDH = 1) of cathepsin K, cathepsin L, cathepsin S, and MMP-9 in three separate GCT-derived mononuclear cell lines (mean SD). Values are based on the number of real-time PCR cycles. Cathepsin L expression was ∼42-fold higher than cathepsin K expression. MMP-9 expression was negligible.

Figure 6.

Cathepsin L-expressing GCT-derived mononuclear cells do not induce osteolysis. Cathepsin L-expressing GCT-derived mononuclear cells were grown on devitalized dentine disks for 21 days. No evidence of bone resorption by these cells was found (A–C). D: A control dentine disk with cultured osteoclasts showing the typical pattern of resorption lines. Representative images were obtained in multiple experiments with three different cell lines (L980, L1050, L1180). Original magnifications, ×400.

Discussion

GCT is characterized by a localized metaphyseal osteolytic process. A number of proteases, such as the MMP gelatinases and stromelysin have been associated with the local aggressive behavior2 but it is unlikely that these proteases are directly responsible for the osteolysis associated with GCT. This report shows that the papain-like cysteine protease cathepsin K, along with the transmembranous proton pump V-ATPase, is abundantly expressed in the multinucleated giant cells and suggests that the cathepsin K/V-ATPase system is primarily responsible for the osteolytic potential of GCT.

A number of MMPs (namely the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9),19 and stromelysin (MMP-3)20 have been implicated in the local aggressive behavior of GCT. However, these proteases are incapable of destabilizing the triple helix in fibrillar collagen, the primary constituent of bone matrix. Degradation of structural collagen depends on the action of specific collagenases, which are able to destabilize the intact triple helix of fibrillar collagen. Destabilized collagen helices can than be further degraded by less specific proteases such as gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9). Hence, degradation of collagen matrix in bone is primarily dependent on the initial action of specific collagenases (ie, the MMP collagenases MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13,9 and possibly MMP-14, or the cathepsin collagenases cathepsin K8,12 and cathepsin L.11).

To identify candidate collagenases in GCT, mRNA expression profiles of MMP and cathepsin collagenases were established by real-time PCR. In line with previous reports we observed massive cathepsin K expression21 and high expression of cathepsin L.22 On the other hand, expression of MMP collagenases was low (MMP-13 and MMP-14) or even below the detection limit of the method (MMP-1 and MMP-8). In contrast, ample expression of the MMP gelatinase, MMP-9 was found. Cellular distribution of the most prominently expressed proteases as elaborated by immunohistochemistry showed that both cathepsin K and MMP-9 were exclusively expressed in the multinucleated giant cells whereas expression of cathepsin L was confined to the mononuclear cells.

Although mRNA expression and immunohistochemistry provide valuable (semiquantitative) information on protein expression and cellular distribution, these approaches do not address the complex regulation of net protease activity. Net protease activity represents a highly regulated process in which final protease activity is dependent on posttranslational processes such as controlled secretion, activation of the inactive proenzyme, and inhibition by specific and nonspecific inhibitors. To address these critical aspects in the regulation of net protease activity, we used specific activity assays9 that address the complex posttranslational regulation of protease activity. In these assays the targeted protease is captured by a specific antibody and after several washing steps, protease activity is quantified through assessment of the proteolytic activation of a modified proenzyme by the captured protease. These assays lack cross-reactivity of conventional chromogenic assays and are insensitive to protease-inhibitor complexes. Moreover, these assays also allow quantification of the amount of latent (pro)-MMP (ie, the potentially activatable pool of MMP) present through activation of latent MMP before the assay.17 Net MMP-13 and MMP-14 (membrane type MMP-1) activity was not found, indicating that these collagenases are primarily present as inactive proenzyme or as protease-inhibitor complex. Net activities of the highly expressed MMP gelatinase MMP-9 were low but high activities were observed after preincubation of the GCT homogenate in the presence of APMA, thus indicating that MMP-9 is predominantly present in an inactive proform and that only a minor fraction of the enzyme is present in as active enzyme.

A novel cathepsin K activity assay, based on the same principle as the MMP activity assays, was used to measure net cathepsin K activity. This assay revealed massive cathepsin K activity, which was more than 100-fold higher than activities found in other tissues expressing cathepsin K (ie, lung,23 atheroma,24 and chondrosarcoma25).

No specific assays are as yet available for the other highly expressed cysteine protease cathepsin L. Traditional peptide-based activity assays lack specificity and are highly influenced by cathepsin K. As yet the role of cathepsin L in bone resorption is unclear: cathepsin L knockout mice develop periodic hair loss and epidermal hyperplasia but apparently do not exhibit any signs of osteosclerosis.26 Reportedly, specific inhibitors of cathepsin L do not interfere with osteoclast-induced bone resorption.27 However, because these osteoclasts do not express cathepsin L,28 these observations do not exclude a role of cathepsin L in GCT-related osteolysis. Immunohistochemistry showed that in contrast to cathepsin K, cathepsin L is preferentially expressed in the mononuclear cell fraction of GCT. To test whether cathepsin L expressed in these cells is involved in bone resorption cathepsin L-expressing GCT-derived mononuclear cell lines were grown to confluence on a dentine disk, a well-established model of bone resorption.29 In this assay no evidence for resorption was found.

Consequently, our findings identify cathepsin K as the primary proteolytic culprit responsible for the osteolysis by GCT. Cathepsin K is highly expressed in osteoclasts and is critically involved in the normal bone homeostasis: overexpression of cathepsin K is associated with an imbalance in bone turnover toward bone loss30 whereas impaired cathepsin K activity is associated with impaired bone resorption. Mutations in the cathepsin K gene underlie the sclerosing bone disorder pycnodysostosis31 and cathepsin K knockout mice show profound osteosclerosis.32 The critical role of cathepsin K in bone homeostasis is further illustrated by the ability of cathepsin K inhibitors to inhibit bone resorption in estrogen-deficient cynomolgus monkeys.33

Cathepsin K is a unique protease because its collagenolytic activity does not solely depend on its ability to destabilize the intact triple helix and that it cleaves the native collagen molecules at more sites than the interstitial collagenases do.10 However, cathepsin K activity and stability is highly influenced by pH34 and the activity and stability of the enzyme is severely impaired at neutral pH or higher.28 In osteoclast-mediated bone resorption an acidic microenvironment is created through proton extrusion mediated by a proton pump belonging to the class of vacuolar H+-ATPases (V-H+-ATPases). Co-expression of V-H+-ATPases and cathepsin K was also found in the multinucleated giant cells, hence these cells are able to create an acidic microenvironment required for cathepsin K activity and stability.

In conclusion, these findings identify cathepsin K as the primary proteolytic culprit in GCT and suggest that the osteoclast-like giant cells are primarily responsible for the osteolysis. Inhibition of cathepsin K33 or its associated proton pump V-H+-ATPase35 may be beneficial as adjuvant treatment especially for those cases for which radical surgical treatment is not possible without substantial functional impairment (sacrum, vertebrae).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Kleemann for the Western blot analysis.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Roeland Hanemaaijer, Ph.D., Department of Biomedical Research, TNO Prevention and Health, PO Box 2215, 2301 CE Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: lindeman@lumc.nl.

Supported by The Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant NHS 2000.B165).

References

- Reid R, Banerjee SS, Sciot R. Giant cell tumour. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Lyon: IARC Press,; World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics, Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 2002:pp 310–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wülling M, Engels C, Jesse N, Werner M, Delling G, Kaiser E. The nature of giant cell tumor of bone. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2001;127:467–474. doi: 10.1007/s004320100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte RE, Wunder JS, Isler MH, Bell RS, Schachar N, Masri BA, Moreau G, Davis AM. Giant cell tumor of the long bone: a Canadian sarcoma group study. Clin Orthop. 2002;397:248–258. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200204000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills BG, Frausto A. Cytokines expressed in multinucleated cells: Paget’s disease and giant cell tumors versus normal bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 1997;61:16–21. doi: 10.1007/s002239900285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng MH, Robbins P, Xu J, Huang L, Wood DJ, Papadimitriou JM. The histogenesis of giant cell tumour of bone: a model of interaction between neoplastic cells and osteoclasts. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:297–307. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. New York: Raven Press,; 1993:pp 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Blair HC, Teitelbaum SL, Ghiselli R, Gluck S. Osteoclastic bone resorption by a polarized vacuolar proton pump. Science. 1989;245:855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.2528207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafienah W, Bromme D, Buttle DJ, Croucher LJ, Hollander AP. Human cathepsin K cleaves native type I and II collagens at the N-terminal end of the triple helix. Biochem J. 1998;331:727–732. doi: 10.1042/bj3310727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingleton WD, Hodges DJ, Brick P, Cawston TE. Collagenase: a key enzyme in collagen turnover. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:759–775. doi: 10.1139/o96-083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aznavoorian S, Moore BA, Alexander-Lister LD, Hallit SL, Windsor LJ, Engler JA. Membrane type I-matrix metalloproteinase-mediated degradation of type I collagen by oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6264–6275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy GK, Dhar SC. Purification and characterization of collagenolytic property of renal cathepsin L from arthritic rat. Int J Biochem. 1992;24:1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(92)90073-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnero P, Borel O, Byrjalsen I, Ferreras M, Drake FH, McQueney MS, Foged NT, Delmas PD, Delaisse JM. The collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is unique among mammalian proteinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32347–32352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motyckova G, Fisher DE. Pycnodysostosis: role and regulation of cathepsin K in osteoclast function and human disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:407–421. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup GB, Lark MW, Veber DF, Bhattacharyya A, Blake S, Dare LC, Erhard KF, Hoffman SJ, James IE, Marquis RW, Ru Y, Vasko-Moser JA, Smith BR, Tomaszek T, Gowen M. Potent and selective inhibition of human cathepsin K leads to inhibition of bone resorption in vivo in a nonhuman primate. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1739–1746. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen JH. Modified proenzymes as substrates for proteolytic enzymes. 1998 doi: 10.1042/bj3230603. US patent 5811252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheijen JH, Nieuwenbroek NM, Beekman B, Hanemaaijer R, Verspaget HW, Ronday HK, Bakker AH. Modified proenzymes as artificial substrates for proteolytic enzymes: colorimetric assay of bacterial collagenase and matrix metalloproteinase activity using modified pro-urokinase. Biochem J. 1997;323:603–609. doi: 10.1042/bj3230603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanemaaijer R, Visser H, Konttinen YT, Koolwijk P, Verheijen JH. A novel and simple immunocapture assay for determination of gelatinase-B (MMP-9) activities in biological fluids: saliva from patients with Sjogren’s syndrome contain increased latent and active gelatinase-B levels. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:657–665. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baici A, Cohen G, Fehr K, Bõni A. A handy assay for collagenase using reconstituted fluorescein-labeled collagen fibrils. Anal Biochem. 1980;108:230–232. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoedel KE, Greco MA, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Ohori NP, Goswami S, Present D, Steiner GC. Expression of metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in giant cell tumor of bone: an immunohistochemical study with clinical correlation. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:1144–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaguri Y, Komiya S, Sugama K, Suzuki K, Inoue A, Morimatsu M, Nagase H. Production of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 3 (stromelysin) by stromal cells of giant cell tumor of bone. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:611–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood-Evans A, Kokubo T, Ishibashi O, Inaoka T, Wlodarski B, Gallagher JA, Bilbe G. Localization of cathepsin K in human osteoclasts by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Bone. 1997;20:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi O, Inui T, Mori Y, Kurokawa T, Kokubo T, Kumegawa M. Quantification of the expression levels of lysosomal cysteine proteinases in purified human osteoclastic cells by competitive RT-PCR. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;68:109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02678149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhling F, Waldburg N, Gerber A, Hackel C, Kruger S, Reinhold D, Bromme D, Weber E, Ansorge S, Welte T. Cathepsin K expression in human lung. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;477:281–286. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI, Chapman HA, Libby P. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:576–583. doi: 10.1172/JCI181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom M, Ekfors T, Bohling T, Aho A, Aro HT, Vuorio E. Cysteine proteinases in chondrosarcomas. Matrix Biol. 2001;19:717–725. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinheckel T, Deussing J, Roth W, Peters C. Towards specific functions of lysosomal cysteine peptidases: phenotypes of mice deficient for cathepsin B or cathepsin L. Biol Chem. 2001;382:735–741. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James IE, Marquis RW, Blake SM, Hwang SM, Gress CJ, Ru Y, Zembryki D, Yamashita DS, McQueney MS, Tomaszek TA, Oh HJ, Gowen M, Veber DF, Lark MW. Potent and selective cathepsin L inhibitors do not inhibit human osteoclast resorption in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11507–11511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake FH, Dodds RA, James IE, Connor JR, Debouck C, Richardson S, Lee-Rykaczewski E, Coleman L, Rieman D, Barthlow R, Hastings G, Gowen M. Cathepsin K, but not cathepsins B, L, or S, is abundantly expressed in human osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12511–12516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyde A, Ali NN, Jones SJ. Resorption of dentine by isolated osteoclasts in vitro. Br Dent J. 1984;24:216–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviranta R, Morko J, Uusitalo H, Aro HT, Vuorio E, Rantakokko J. Accelerated turnover of metaphyseal trabecular bone in mice overexpressing cathepsin K. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1444–1452. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motyckova G, Fisher DE. Pycnodysostosis: role and regulation of cathepsin K in osteoclast function and human disease. Curr Mol Med. 2002;2:407–421. doi: 10.2174/1566524023362401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen M, Lazner F, Dodds R, Kapadia R, Feild J, Tavaria M, Bertoncello I, Drake F, Zavarselk S, Tellis I, Hertzog P, Debouck C, Kola I. Cathepsin K knockout mice develop osteopetrosis due to a deficit in matrix degradation but not demineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1654–1663. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.10.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup GB, Lark MW, Veber DF, Bhattacharyya A, Blake S, Dare LC, Erhard KF, Hoffman SJ, James IE, Marquis RW, Ru Y, Vasko-Moser JA, Smith BR, Tomaszek T, Gowen M. Potent and selective inhibition of human cathepsin K leads to inhibition of bone resorption in vivo in a nonhuman primate. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1739–1746. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Hou WS, Bromme D. Collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is specifically modulated by cartilage-resident chondroitin sulfates. Biochemistry. 2000;39:529–536. doi: 10.1021/bi992251u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina C, Gagliardi S, Nadler G, Morvan M, Parini C, Belfiore P, Visentin L, Gowen M. Novel bone antiresorptive agents that selectively inhibit the osteoclast V-H+-ATPase. Farmaco. 2001;56:113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0014-827x(01)01013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]