Abstract

Pbx proteins comprise a family of TALE (three amino acid loop extension) class homeodomain transcription factors that are implicated in developmental gene expression through their abilities to form hetero-oligomeric DNA-binding complexes and function as transcriptional regulators in numerous cell types. We demonstrate here that one member of this family, Pbx3, is expressed at high levels predominantly in the developing central nervous system, including a region of the medulla oblongata that is implicated in the control of respiration. Pbx3-deficient mice develop to term but die within a few hours of birth from central respiratory failure due to abnormal activity of inspiratory neurons in the medulla. This partially phenocopies the defect in mice deficient for Rnx, a metaHox homeodomain transcription factor, that we demonstrate here is capable of forming a DNA-binding complex with Pbx3. Rnx expression is unperturbed in Pbx3-deficient mice, but its ability to enhance transcription in vitro as a complex with TALE proteins is compromised in the absence of Pbx3. Thus, Pbx3 is essential for respiration and, like its DNA-binding partner Rnx, is critical for proper development of medullary respiratory control mechanisms. Pbx3-deficient mice provide a model for congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and suggest that Pbx3 mutations may promote the pathogenesis of this disorder.

Pbx proteins comprise a set of four TALE (three amino acid loop extension) class homeodomain transcription factors1–4 that are implicated in developmental gene expression. They form hetero-oligomeric DNA-binding complexes and function as transcriptional regulators in cells of different developmental lineages.5 Pbx proteins are orthologs of Drosophila extradenticle,6 which contributes to axial and limb patterning,7 eye development,8 and patterning of the embryonic peripheral nervous system.9 Similarly, loss-of-function studies in knockout mice demonstrate a role for Pbx1 in patterning and morphogenesis.10–13 Most organs are abnormally developed in Pbx1−/− embryos and some of the observed deficiencies in organogenesis and cellular differentiation appear to result from compromise of orphan Hox proteins.12 To further define the developmental roles of Pbx proteins and their potential isotype-specific contributions, we have determined the expression pattern of Pbx3 and created Pbx3-deficient mice. We report here that lack of Pbx3 results in neonatal death due to central respiratory failure, a phenotype similar to that of mice deficient for Rnx,14 a metaHox protein that is also expressed in the medulla and capable of associating with Pbx3 in a higher-order DNA-binding transcriptional complex. Our studies implicate Pbx3 as being critical for development of central control of respiration in vertebrates and suggest the broader hypothesis that mutations of Pbx3, its cofactors, or its regulators may promote the pathogenesis of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Pbx3 Null Mice

The Pbx3 gene was mutated by deletion of a HindIII-BamH1 fragment spanning exon 3 and replacement with a PGK neo cassette (from the pNT vector) in opposite transcriptional orientation. The Pbx3 deletion creates an early frame-shift mutation that causes termination of the Pbx3 reading frame upstream of its dimerization and DNA-binding domains. A 12-kb XbaI-EcoR1 fragment of genomic DNA spanning the disrupted Pbx3 exon 3 was then cloned into the targeting vector. Homologous recombinant clones were identified by Southern blot analyses. Out of 132 informative clones, 8 were identified as homologous recombinants. Euploid clones were microinjected into C57BL/6 host blastocysts, which were then implanted in pseudo-pregnant females. Chimeric male mice were backcrossed with wt C57BL/6 females to obtain germline transmission of the targeted allele. Phenotypes were analyzed in neonates derived from third backcross generations on a C57BL/6 background.

Antibodies and Immunohistochemistry

Monoclonal antibodies were raised against maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion proteins containing the 80 or 30 carboxy-terminal amino acids of human Pbx3a or Pbx3b, respectively. Specificity for Pbx3 proteins was established by Western blot analysis of in vitro translated Pbx family proteins (Pbx1, 2, and 3). Anti-Rnx rabbit antisera were raised against an affinity-purified MBP-Rnx fusion protein containing the 75 C-terminal amino acids of mouse Rnx. Immune sera were purified by Protein A Sepharose affinity chromatography (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and their specificity determined by Western blot analysis of in vitro translated Hox11 family proteins.

Embryos were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin using standard procedures. Sectioned tissues were stained with anti-Pbx3a (0.008 mg/ml), anti-Pbx3b (0.04 mg/ml), or anti-Meis15 (0.043 mg/ml) monoclonal antibodies followed by biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:150). Immune complexes were visualized using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) and DAB chromagen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For Rnx/Pbx3 co-localization, paraffin sections were stained with anti-Rnx (1:25) and Pbx3a (0.16 mg/ml) antibodies. Secondary antibodies (1:150) consisted of Texas red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Accurate Antibodies, Westbury, NY) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Accurate Antibodies). Stained slides were mounted in DAPI-containing slide mount medium with antiquench (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) and examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Respiratory Analyses

Whole body plethysmography was performed on P0 mice less than 1 day of age.16 Respiratory frequency, tidal volume, and minute volume were calculated from 50 to 70 respiratory cycles during quiet breathing. Medulla and spinal cords for in vitro preparations were isolated from P0 mice under deep ether anesthesia as described previously.14,17,18 Respiratory-like activity corresponding to the inspiration rhythm was monitored at the C4/C5 ventral root through a glass capillary suction electrode and a high-pass filter with a 0.3 seconds time constant. Values are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (analysis of variance) for all three genotypes. Significant differences between groups were identified using post-hoc Bonferroni tests. Membrane potentials of inspiratory neurons in the ventrolateral medulla19 were recorded using conventional whole-cell patch-clamp methods.20 The membrane potentials were recorded with a single-electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (CEZ-3100, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) after compensation of the series resistance (25 to 50 mol/LΩ) and capacitance.

DNA-Binding and Transcriptional Assays

Proteins used in DNA-binding assays were produced in vitro from SP6 expression plasmids using a coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate system (Promega, Madison, WI). The DNA probe consisted of a gel-purified, end-labeled, double-stranded oligonucleotide encoding a modified HoxB2 r4 enhancer,15 containing consensus Pbx and Meis sites and a Hox site that was altered to favor binding by Rnx.21 Transient transfection assays were performed as described22 using a pGL3 luciferase reporter (driven by SV40 early promoter containing one copy of the modified HoxB2 r4 enhancer) and internal control (pCMV-1 β-gal) plasmids. Luciferase activity was measured in light units using a Monolight 2010 luminometer; β-gal activity was used to normalize luciferase activity to account for differences in transfection efficiency.

Results

Pbx3 Is Expressed in the Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

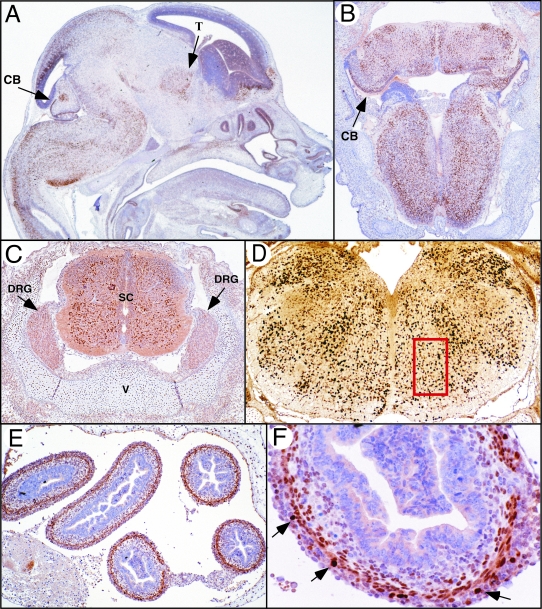

Pbx3 expression was studied using immunohistochemical staining methods using highly specific monoclonal antibodies directed against two different isoforms (Pbx3a and Pbx3b) that arise from differential splicing of the Pbx3 RNA.3 Pbx3a was present throughout the mesenchyme at early gestational days, but was progressively more restricted to tissues of the developing central nervous system (CNS) by E11.5 (data not shown). At E15, nuclear Pbx3a (and to a much lesser extent Pbx3b) staining was observed in the dorsal thalamus, cerebellum, pons, medulla, dorsal root ganglia, and neurons in both the ventral and dorsal columns of the spinal cord (Figure 1A to D). Staining was most intense throughout the medulla (Figure 1, A and D) and was present in regions that overlap with those involved in central control of respiration.23 Pbx3a was also found at high levels in myenteric neurons and at lower levels in smooth muscle myocytes of the intestine (Figure 1, E and F). Even at late gestational days, Pbx3a was not exclusively confined to the nervous system, as lower levels were also observed in chondrocytes throughout the axial and appendicular skeleton (Figure 1C).

Figure 1-4275.

Pbx3 expression in the CNS. Immunohistochemistry was performed using a monclonal antibody directed against Pbx3a on paraffin-embedded tissue sections. A: A sagittal section near the midline of a wild-type C57BL/6 embryo at E15.5 shows presence of Pbx3a protein, as evidenced by intense nuclear staining (brown), in the dorsal thalamus (T), the roof of the midbrain, and the cortex and internal cerebellar primordia (CB). Pbx3 is most widely expressed in the hindbrain, particularly in the medulla. B: A coronal section from E15.5 shows Pbx3a protein in the medulla and cerebellar primordia (CB). C: Transverse section through the spinal cord shows Pbx3 in both the ventral and dorsal portions of the spinal cord (SC). Less intense staining can be seen in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG). Robust staining of chondrocytes in the vertebra (V) is present. D: A coronal section of the caudal medulla shows abundant Pbx3 throughout the medulla, including cells in the ventral respiratory column (indicated by red box). E and F: Transverse sections of the bowel (B) at E15.5 show expression of Pbx3a in nuclei of myenteric ganglion cells (arrows) and smooth muscle myocytes of the muscularis. Magnifications: A, B, and D, ×25; C, ×60; E, ×40; F, ×400.

Generation of Pbx3-Deficient Mice

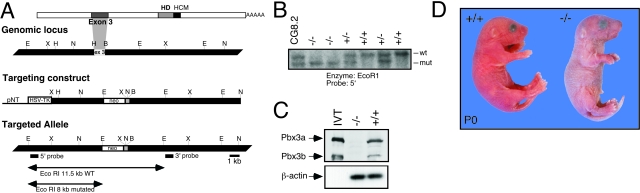

To assess the functional role of Pbx3, gene targeting was used to generate Pbx3-deficient (Pbx3−/−) mice (Figure 2A). Chimeric male mice carrying the Pbx3 null allele were bred with wild-type C57BL/6 mice until the allele was transmitted through the germline as determined by Southern blot analysis (Figure 2B). Mice heterozygous for the targeted Pbx3 gene were viable and fertile. They developed normally and showed no histopathological abnormalities. Intercross matings of Pbx3+/− mice, however, did not yield viable Pbx3−/− mice at 3 weeks of age (0 of 155 pups, P < 0.001). A high number of dead pups were observed at P0, and most were found to be null for Pbx3. Analysis of all neonates showed a Mendelian distribution of genotypes (wild-type, 23 of 93, 25%; Pbx3+/−, 49 of 93, 53%; Pbx3−/−, 21 of 93, 23%) indicating that the absence of Pbx3 did not result in embryonic lethality. Western blot analysis confirmed the lack of Pbx3 protein in the brains of late gestation Pbx3−/− embryos (Figure 2C).

Figure 2-4275.

Construction of Pbx3 null mice. A: A schematic representation of the mouse Pbx3 cDNA, genomic locus, targeting vector, and mutated allele following homologous recombination. In the Pbx3 cDNA, sequences derived from exon 3 and the homeodomain (HD) are shown as shaded boxes. Approximately 20 kb of the Pbx3 locus flanking exon 3 (white box) are depicted along with mapped restriction sites. The targeting construct carries a PGK-neo cassette, which replaces Pbx3 exon3, and the HSV-tk gene, shown as solid white boxes. The transcriptional orientation of the Pbx3 arms of homology is opposite to that of the PGK-neo cassette. The 5′ and 3′ external probes used for Southern blot analyses are shown as solid black boxes below the mutated allele. Restriction enzymes sites: B, BamH1; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NheI; X, XbaI. B: Southern blot analysis of Pbx3 alleles. DNA from ES cells (CG8.2) and mouse tissues was analyzed with probes and enzymes indicated beneath the panel. Wt (11.5 kb) and mutant (8 kb) Pbx3 alleles are indicated to the right. C: Western blot analysis of Pbx3 expression. Protein extracts prepared from brain tissue of E16 embryos were subjected to Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibodies specific for the Pbx3a and Pbx3b isoforms. Genotypes determined by Southern blotting are listed at the top of the panel. Left lane contains in vitro translated Pbx3a and Pbx3b proteins. Migrations of Pbx3 protein isoforms and β-actin loading controls are indicated on the left. D: Gross appearance of pups within a few hours of birth shows marked cyanosis of the Pbx3 newborn (right) compared to a wt littermate (left).

Close observation showed that Pbx3−/− pups were viable at birth with intact heart rate but died within a few hours. They appeared apneic and developed marked cyanosis shortly after birth (Figure 2D). Gross anatomical examination of Pbx3−/− mice showed that all internal organs were present, properly developed, and of appropriate size; however the lungs were not inflated indicating an absence of appropriate ventilation. Neurofilament staining of E10.5 embryos showed no gross abnormalities of cranial nerve ganglia, indicating correct specification of hindbrain rhombomeres and associated cranial nerve nuclei (data not shown). The brain and spinal cord appeared grossly normal in Pbx3−/− mice at P0 and no histological abnormalities of the cranial nerves, ganglia, or brainstem nuclei were observed. No apparent neuronal loss or gliosis was observed in the brainstem, including areas of the ventral medulla implicated in respiratory control and associated with high-level Pbx3 expression.

Pbx3-Deficient Mice Exhibit Central Hypoventilation

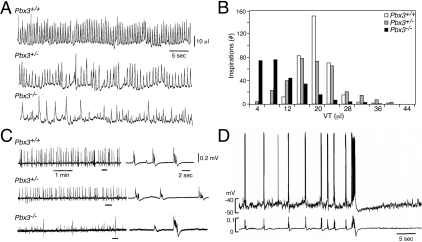

The physiological abnormality in Pbx3−/− mice was examined by monitoring spontaneous inspiration, using whole body plethysmography.16 The respiratory pattern in Pbx3−/− mice exhibited a marked irregularity of the tidal volume in each respiratory cycle (Figure 3, A and B). In addition, the average respiratory frequency of 81 ± 35 per minute in Pbx3−/− mice was significantly lower than that observed in Pbx3+/− and wild-type (wt) mice (Table 1). As a consequence, the mean respiratory minute volume of 0.72 ± 0.29 ml/min in Pbx3−/− mice was significantly lower than that of wt (1.57 ± 0.62 ml/min; P < 0.01) and Pbx3+/− mice, suggesting that hypoventilation was a likely cause of death within several hours after birth.

Figure 3-4275.

Respiratory analysis of Pbx3-deficient mice. A: Spontaneous inspiratory activity of newborn mice. Plethysmographic recordings correspond to spontaneous inspiration in Pbx3−/−, Pbx3+/− and wt littermates, respectively. B: Amplitude histograms of tidal volume (VT) in different genotypes calculated from recording data shown in A. The number of respiratory cycles measured were 144 (Pbx3−/−), 196 (Pbx3+/−) and 192 (wt). C: C4 ventral root inspiratory activity in medulla-spinal cord preparations of newborn mice. Faster sweep representations are shown on the right for parts denoted by bars on the left. D: Membrane potential recordings of an inspiratory neuron in the ventrolateral medulla of a Pbx3−/− mouse. Top tracing, membrane potential trajectory from an inspiratory neuron recorded using conventional whole-cell patch-clamp method; bottom tracing, simultaneous recording of C4 ventral root inspiratory activity. Coordinate patterns are seen in which inspiratory bursts with short duration are followed by a subsequent large burst of long duration followed by apnea.

Table 1.

In Vivo and in Vitro Respiratory Activity of Pbx3-Deficient Mice

|

In vivo respiratory activity measured by plethysmography | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Frequency (per min) | Tidal volume (μl) | Minute volume (ml/min) |

| +/+ (n = 7) | 124 ± 24 | 12.6 ± 4.5 | 1.57 ± 0.62 |

| +/− (n = 9) | 124 ± 38 | 11.8 ± 4.9 | 1.47 ± 0.91 |

| −/− (n = 8) | 81 ± 35* | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 0.72 ± 0.29† |

| C4 inspiratory activity recorded in vitro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Frequency (per min) | Duration (ms) | Amplitude (μV) |

| +/+ (n = 8) | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 934 ± 371 | 246 ± 73 |

| +/− (n = 15) | 8.1 ± 1.4 | 958 ± 275‡ | 159 ± 52§ |

| −/− (n = 11) | 9.0 ± 2.1* | 713 ± 239† | 65 ± 35* |

, p < 0.01 compared to +/+ and +/−.

, p < 0.05 compared to +/+ and +/−.

, p < 0.05 compared to +/+.

, p < 0.01 compared to +/+.

To localize the level of the defect in Pbx3−/− mice, C4 ventral nerve root activity was recorded in medulla-spinal cord preparations in vitro as a measure of respiratory output. Ventral C4/C5 activity has been shown to be synchronous with phrenic nerve discharge and contraction of inspiratory intercostal muscles.17 The C4 ventral root recordings from Pbx3−/− mice showed a characteristic pattern of motoneuronal outputs, consisting of small bursts at a frequency of 6 to 13 per minute, interspersed with large bursts appearing at a frequency of 0.2 to 0.5 per minute (Figure 3C). The latter bursts were usually followed by apnea (up to 30 seconds), or by bursts with minimum activity whose amplitude gradually recovered with time. Mean values of parameters of C4 inspiratory activity revealed a significantly higher frequency but lower amplitude of the bursts in the medulla-spinal cord preparations of Pbx3−/− mice (Table 1). This reduced amplitude likely produces insufficient pressure changes by ventilatory movement in some respiratory cycles leading to a significant decrease of minute respiratory volume in Pbx3−/− mice.

To investigate whether the altered inspiratory pattern of Pbx3−/− mice may result from abnormal function of respiratory centers in the medulla, we assessed the membrane potentials of inspiratory neurons in this region.19,24,25 The membrane potential trajectory of inspiratory neurons (n = 6) in Pbx3−/− mice correlated with the pattern of C4 motoneuronal outputs (Figure 3D). The coordinate patterns indicate that an underlying basis for respiratory failure in Pbx3−/− mice is, at least in part, dysfunction of central respiratory networks in the medulla.

Pbx3 and Rnx Are Co-Expressed in Neurons of the Medulla

Neonatal death due to a central hypoventilation syndrome has been reported in Rnx-deficient mice.14Rnx is a member of the Hox11 orphan homeobox gene family,26,27 whose representatives contain DNA-binding homeodomains that differ in their recognition helix from those encoded by clustered Hox genes,28 but contain conserved motifs (hexapeptide) implicated in Pbx dimerization.29 Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that both Rnx and Pbx3a proteins were present in the nuclei of neurons of the caudal portion of the medulla (Figure 4A). Since the nuclear localization of Pbx proteins is dependent on dimerization with TALE class homeoproteins of the Meis/Pknox1 family,30 we also examined the distribution of Meis protein expression in the medulla. Meis proteins were present in the nuclei of neurons whose distribution extensively overlapped with those expressing Pbx3a (Figure 4B), consistent with a Meis-mediated mechanism for Pbx3 nuclear import.31 Furthermore, the nuclear co-localization of Rnx and Meis proteins was unaltered in Pbx3−/− mice (Figure 4C), demonstrating that neither the expression nor nuclear localization of either protein was dependent on Pbx3.

Figure 4-4275.

Co-localization of Pbx3 and Rnx in hindbrain neurons. A: Immunohistochemical analysis of Pbx3a in a coronal section of the medulla oblongata in wt E15 embryo (magnification, ×25). Red box corresponds to the fields examined by immunofluorescence at higher magnification. Pbx3a (green) and Rnx (red) are co-localized in neurons as evidenced by the merged image (yellow) obtained by fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×600). DAPI stain (blue) highlights nuclei. B: Immunohistochemical analysis of wt embryos at E15 shows similar patterns of expression for Pbx3a and Meis proteins in coronal sections of the medulla (magnification, ×40). C and D: Immunohistochemical analysis shows nuclear expression of Meis and Rnx in Pbx3−/− mice (magnification, ×125).

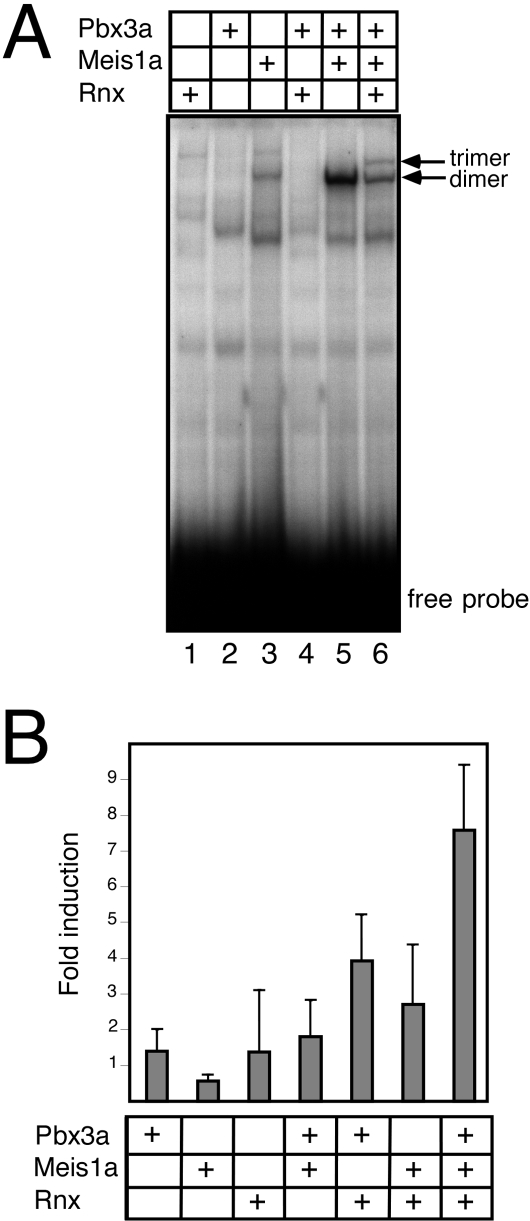

Pbx3 Forms a DNA-Binding Transcriptional Complex with Rnx

Expression of Rnx, Pbx3, and Meis in the medulla raised the possibility that they function together as a hetero-oligomeric complex whose transcriptional activity may be altered by the lack of Pbx3. Therefore, their ability to form a DNA-binding complex was examined on a modified endogenous enhancer that contained consensus sites for all three proteins. This genetically defined response element (Hoxb2 r4) has been shown to rely on combinatorial interactions between Hox and TALE proteins to mediate appropriate HoxB2 developmental expression in vivo.15,32 For the current studies, we modified the Hox consensus site to optimize for recognition by the divergent homeodomain of Rnx.21 As expected, in vitro-produced Pbx3a and Meis1a formed a dimeric complex on this enhancer element (Figure 5A, lane 5). Addition of Rnx resulted in the formation of an additional slower migrating band consistent with formation of a trimeric complex (Figure 5A, lane 6), similar to those observed in previous studies of Hoxb1 and Hoxa9.15,33 This indicated that Rnx has the capacity to assemble into a higher order, trimeric DNA-binding complex with TALE homeodomain proteins Pbx3 and Meis1a.

Figure 5-4275.

Pbx3 forms a DNA-binding transcriptional complex with Rnx and Meis. A: Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed with in vitro produced Pbx3a, Meis1a, and Rnx proteins. The DNA probe consisted of a modified HoxB2 r4 enhancer, which contains sites for Pbx, Meis, and Hox binding. The Hox site was altered to provide optimal binding for Rnx. A trimeric complex with slower mobility than the dimeric Pbx3a-Meis1a complex (lane 5) was observed in the presence of Pbx3a, Meis1a, and Rnx (lane 6). Lane contents are indicated at top. B: A transient transfection assay was performed using a reporter construct containing the modified HoxB2 r4 enhancer positioned upstream of a minimal promoter/luciferase gene. Expression constructs for Pbx3a, Meis1a, and Rnx were co-transfected alone or in combination. Increased transcriptional activation was observed in the presence of Pbx3a, Meis 1a, and Rnx compared to that observed with various dimeric combinations. Lane contents are indicated below.

To assess the functional consequences of trimeric Rnx/Pbx3/Meis interactions, transient transfection assays were performed. For these studies, a reporter gene that contained the modified enhancer situated upstream of the SV40 promoter was used in human embryonic kidney cells, which are permissive for Hox transcriptional activity. Co-transfection of expression constructs Pbx3a and Meis1a displayed minimal activation above background (Figure 5B), as previously noted for comparable TALE heterodimers.15,33 Co-transfection of Rnx, Pbx3a, and Meis1a, however, resulted in a 7.5-fold activation above background levels of transcription obtained with Rnx alone. In contrast, Rnx and Meis1a in the absence of Pbx3a displayed a reduced level of activation that approximated only a third of that observed in the presence of all three homeodomain proteins (Figure 5B). These data reveal trimeric interactions between Rnx, Pbx3a, and Meis1a function to promote heightened transcriptional activation, and highlight the critical role of Pbx3a in trimeric transcriptional activity.

Discussion

The respiratory pattern in Pbx3−/− mice is characterized by irregular amplitude of inspiration and reduced respiratory frequency. Although a higher than normal frequency of C4 inspiratory neuronal activity is observed in the in vitro brainstem preparations of Pbx3−/− mice, the burst amplitude of the phrenic motoneurons is significantly smaller than wt. This reduced amplitude likely produces insufficient pressure changes by ventilatory movement in some respiratory cycles leading to a significant decrease of minute respiratory volume in Pbx3−/− mice, and appears insufficient to fully inflate the lungs. Importantly, the coordinate patterns of membrane potentials for inspiratory neurons in the ventrolateral medulla and C4 motoneuronal outputs indicate that an underlying basis for respiratory failure in Pbx3−/− mice is dysfunction of central respiratory networks in the medulla. We cannot exclude a possibility that abnormality of afferent inputs contributes to respiratory dysfunction in vivo.

Dysfunction of central respiratory networks has been reported in Rnx-deficient mice.14Rnx is one of three Hox11-related orphan homeobox genes that encode homeodomain-containing transcription factors, which also possess conserved motifs implicated in Pbx dimerization. Our studies herein demonstrate that Pbx3 forms a DNA-binding complex with Rnx and enhances its transcriptional properties. Although the three family members (Hox11, Rnx, and Enx) display extensively overlapping patterns of embryonic expression, mice deficient for each display major phenotypes at sites where the mutated gene is singularly expressed,14,34–36 which is the medulla for Rnx. The respiratory pattern in Rnx−/− mice is characterized by more frequent and prolonged apneas than Pbx3−/− mice, possibly reflecting the contributions of non-dependent functions of the respective proteins. The respiratory defect in Rnx-deficient mice has recently been proposed to result from compromised development of the nucleus of the solitary tract, a major relay station for visceral sensory afferents in the medulla,37 as opposed to primary defects of rhythmic respiratory neurons. The Rnx-related Hox11, as well as Rnx, is also required for proper development of most relay sensory neurons.38 More refined analyses are required to determine whether Pbx3 may contribute to development of relay somatic sensory neurons and whether the Pbx3 respiratory defect results from compromise of Rnx and/or Hox11 function. Nevertheless, deficiencies of either Pbx3 or Rnx, which are capable of forming active transcriptional complexes in vitro, result in abnormal respiration attributable in part to dysfunction of hindbrain neurons.

Mice deficient for clustered Hox genes display reorganization of the hindbrain (Hoxa1, a2),39–41 defects in cranial nerve nuclei (Hoxb1, b2, and a2),41–44 or branchial arch homeotic transformation (Hoxa2).41 These do not appear to be features of Pbx3−/− mice, despite previous studies implicating Pbx TALE homeodomain proteins in the regulation of Hoxb1 and Hoxb2 expression in the embryonic hindbrain.15,32,45,46 Hindbrain patterning phenotypes, however, have been noted in Pbx1−/− embryos,10 suggesting independent roles for Pbx family proteins in hindbrain development. Pbx3−/− mice also contrast with Krox-20−/− mice, in which rhombomeres 3 and 5 are eliminated and deficits in rhythmic activity were localized to the pontine reticular formation, not the ventral medullary respiratory center.47

Defects in the amplitude and frequency of breathing are characteristic of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS), which results in potentially lethal hypoxia. Thus, Pbx3−/− mice may be a model for CCHS, similar to previous suggestions for Rnx-deficient mice,14 implicating downstream pathways regulated by hetero-oligomeric Pbx3 transcriptional complexes as critical for development of hindbrain neurons involved in control of respiration. The molecular pathogenesis of CCHS is known for only the small subset of patients harboring mutations of the RET/GDNF and EDNRB/EDN3 receptor/ligand pairs.48 Up to 50% of patients with CCHS also manifest Hirschsprung’s disease,49 a clinical constellation referred to as Haddad syndrome, characterized by congenital failure of autonomic control of ventilation and gastrointestinal motility.50 Mice that are deficient for Enx, another Hox11-related orphan homeobox gene, are characterized by hyperganglionic megacolon.36 Interestingly, Pbx3 is also expressed at high levels in myenteric ganglionic neurons of the ileum and colon raising the possibility that loss of Pbx3 may also compromise Enx function, which, as a close homolog of Rnx, would be expected to bind DNA as a complex with Pbx3. Due to the demise of Pbx3−/− mice within hours of birth, we were unable to evaluate for development of megacolon. Nevertheless, our studies suggest the broader hypothesis that mutations of Pbx3, its cofactors, targets, or regulators may promote the pathogenesis of a subset of CCHS, which warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Stevens, Cita Nicolas, Maria Ambrus, and Bich Tien Rouse for technical assistance, the Stanford Transgenic Facility for blastocyst injections, Eva Pfendt and Elizabeth Domonay for immunohistochemistry, Carolyn Tudor for photographic assistance, John Manak for microscopy, Peter Nagy for helpful comments, and Leah Spalding for statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Michael L. Cleary at the Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford CA 94305. E-mail: mcleary@stanford.edu.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants (CA42971, CA70404, and CA90735) and by Public Health Service training grant AI07290 awarded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (J.W.R.).

Current address for L.S. is the Graduate Program of Molecular Biology, Cornell/Sloan-Kettering, Institute of Genetic Medicine, Whitney Tower, W-406, Cornell University Medical School, 1300 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021.

References

- Nourse J, Mellentin JD, Galili N, Wilkinson J, Stanbridge E, Smith SD, Cleary ML. Chromosomal translocation t(1;19) results in synthesis of a homeobox fusion mRNA that codes for a potential chimeric transcription factor. Cell. 1990;60:535–545. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90657-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps MP, Murre CM, Sun X-H, Baltimore D. A new homeobox gene contributes the DNA-binding domain of the t(1;19) translocation protein in pre-B ALL. Cell. 1990;60:547–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monica K, Galili N, Nourse J, Saltman D, Cleary ML. PBX2 and PBX3, new homeobox genes with extensive homology to the human proto-oncogene PBX1. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6149–6157. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K, Mincheva A, Korn B, Lichter P, Pöpperl H. Pbx4, a new Pbx family member on mouse chromosome 8, is expressed during spermatogenesis. Mech Dev. 2001;103:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RS, Affolter M. Hox proteins meet more partners. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:423–429. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C, Peiper M, Weischaus E. Extradenticle, a regulator of homeotic gene activity, is a homolog of the homeobox-containing human proto-oncogene, Pbx1. Cell. 1993;74:1101–1112. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercader N, Leonardo E, Azpiazu N, Serrano A, Morata G, Martinez C, Torres M. Conserved regulation of proximodistal limb axis development by Meis1/Hth. Nature. 1999;402:425–429. doi: 10.1038/46580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai CY, Kuo TS, Jaw TJ, Kurant E, Chen CT, Bessarab DA, Salzberg A, Sun YH. The homothorax homeoprotein activates the nuclear localization of another homeoprotein, extradenticle, and suppresses eye development in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:435–446. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurant E, Pai CY, Sharf R, Halachmi N, Sun YH, Salzberg A. Dorsotonals/homothorax, the Drosophila homologue of meis1, interacts with extradenticle in patterning the embryonic PNS. Development. 1998;125:1037–1048. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selleri L, Depew MJ, Jacobs Y, Chanda SK, Tsang KY, Cheah K, Rubenstein JLR, O’Gorman S, Cleary ML. Requirement for Pbx1 in skeletal patterning and programming chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2001;128:3543–3557. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.18.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMartino J, Selleri L, Traver D, Firpo M, Rhee JW, Warnke R, O’Gorman S, Weissman IL, Cleary ML. The Hox cofactor and proto-oncogene Pbx1 is required for maintenance of definitive hematopoiesis in the fetal liver. Blood. 2001;98:618–626. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Selleri L, Lee JS, Zhang AY, Gu X, Jacobs Y, Cleary ML. Pbx1 inactivation disrupts pancreas development and in Ipf1-deficient mice promotes diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 2002;30:430–435. doi: 10.1038/ng860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel CA, Godin RE, Cleary ML. Pbx1 regulates nephrogenesis and ureteric branching in the developing kidney. Dev Biol. 2002;254:262–276. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasawa S, Arata A, Onimaru H, Roth KA, Brown GA, Horning S, Arata S, Okumura K, Sasazuki T, Korsmeyer SJ. Rnx deficiency results in congenital central hypoventilation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:287–290. doi: 10.1038/73516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Y, Schanbel CA, Cleary ML. Trimeric association of Hox and TALE homeodomain proteins mediates HoxB2 hindbrain enhancer activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5134–5142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwaki T, Cao W, Kurihara Y, Kurihara H, Ling G, Onodera M, Ju K, Yazaki Y, Kumada M. Impaired ventilatory responses to hypoxia and hypercapnea in mutant mice deficient in endothelin-1. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:1279–1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzue T. Respiratory rhythm generation in the in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparation of the neonatal rat. J Physiol. 1984;354:173–183. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Arata A, Homma I. Primary respiratory rhythm generator in the medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rat. Brain Res. 1988;445:314–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata A, Onimaru H, Homma I. Respiration-related neurons in the ventral medulla of newborn rats in vitro. Brain Res Bull. 1990;24:599–604. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90165-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H, Homma I. Whole cell recordings from respiratory neurons in the medulla of brainstem-spinal cord preparations isolated from newborn rats. Plugers Arch. 1992;420:399–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00374476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen WF, Chang CP, Rozenfeld S, Sauvageau G, Humphries RK, Lu M, Lawrence HJ, Cleary ML, Largman C. Hox homeodomain proteins exhibit selective complex stabilities with Pbx and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:898–906. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.5.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rocco G, Mavilio G, Zappavigna V. Functional dissection of a transcriptionally active, target-specific Hox-Pbx complex. EMBO J. 1997;16:3644–3654. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi AL, Denavit-Saubie M, Champagnat J. Central control of breathing in mammals: neuronal circuitry, membrane properties, and neurotransmitters. Am Phys Soc. 1995;75:1–45. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru H. Studies of the respiratory center using isolated brainstem-spinal cord preparations. Neurosci Res. 1995;21:183–190. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)00863-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickling JC, Champagnat J, Denavit-Saubie M. Electroresponsive properties and membrane potential trajectories of three types of inspiratory neurons in the newborn mouse brain stem in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:795–810. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano M, Roberts CWM, Minden M, Crist WM, Korsmeyer SJ. Deregulation of a homeobox gene, HOX11, by the t(10;14) in T-cell leukemia. Science. 1991;253:79–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1676542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy MA, Gonzalez-Sarmiento R, Kees UR, Lampert F, Dear N, Boehm T, Rabbitts TH. HOX11, a homeobox-containing T-cell oncogene on human chromosome 10q24. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:8900–8904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.8900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear TN, Sanchez-Garcia I, Rabbitts TH. The HOX11 gene encodes a DNA-binding nuclear transcription factor belonging to a distinct family of homeobox genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4431–4435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CP, Shen WF, Rozenfeld S, Lawrence HJ, Largman C, Cleary ML. Pbx proteins display hexapeptide-dependent cooperative DNA binding with a subset of Hox proteins. Genes Dev. 1995;9:663–674. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelsen J, Kilstrup-Nielsen C, Blasi F, Mavilio F, Zappavigna V. The subcellular localization of PBX1 and EXD proteins depends on nuclear import and export signals and is modulated by association with PREP1 and HTH. Genes Dev. 1999;13:946–953. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toresson H, Parmar M, Campbell K. Expression of Meis and Pbx genes and their protein products in the developing telencephalon: implications for regional differentiation. Mech Dev. 2000;94:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E, Marshall H, Popperl H, Maconochie M, Krumlauf R, Blasi F. Segmental expression of Hoxb2 in r4 requires two separate sites that integrate cooperative interactions between Prep1, Pbx, and Hox proteins. Development. 2000;127:155–166. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel CA, Jacobs Y, Cleary ML. HoxA9-mediated immortalization of myeloid progenitors requires molecular interactions with TALE cofactors Pbx and Meis. Oncogene. 2000;19:608–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts CWM, Shutter JR, Korsmeyer SJ. Hox11 controls genesis of the spleen. Nature. 1994;368:747–749. doi: 10.1038/368747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear TN, Colledge WH, Carlton MB, Lavenir I, Larson T, Smith AJ, Warren AJ, Evans MJ, Sofroniew MV, Rabbitts TH. The Hox11 gene is essential for cell survival during spleen development. Development. 1995;121:2909–2915. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasawa S, Yunker AMR, Roth KA, Brown GA, Horning S, Korsmeyer SJ. Enx (Hox11L1)-deficient mice develop myenteric neuronal hyperplasia and megacolon. Nat Med. 1997;3:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Fritzsch B, Shirasawa S, Chen C-L, Choi Y, Ma Q. Formation of brainstem (nor)adrenergic centers and first-order relay visceral sensory neurons is dependent on homeodomain protein Rnx/Tlx3. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2533–2545. doi: 10.1101/gad.921501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Shirasawa S, Chen C-L, Cheng L, Ma Q. Proper development of relay somatic sensory neurons and D2/D4 interneurons requires homeobox genes Rnx/Tlx-3 and Tlx-1. Gene Dev. 2002;16:1220–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.982802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter EM, Goddard JM, Chisaka O, Manley NR, Capecchi MR. Loss of Hox-A1 (Hox-16) function results in the reorganization of the murine hindbrain. Development. 1993;118:1063–1075. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Lufkin T, Vonesch JL, Ruberte E, Olivo JC, Dolle P, Gorry P, Lumsden A, Chambon P. Two rhombomeres are altered in Hoxa-1 mutant mice. Development. 1993;119:319–338. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavalas A, Davenne M, Lumsden A, Chambon P, Rijli FM. Role of Hoxa-2 in axon pathfinding and rostral hindbrain patterning: development. 1997;124:3693–3702. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer M, Lumsden A, Ariza-McNaughton L, Bradley A, Krumlauf R. Altered segmental identity and abnormal migration of motor neurons in mice lacking Hoxb-1. Nature. 1996;384:630–634. doi: 10.1038/384630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard JM, Rossel M, Manley NR, Capecchi MR. Mice with targeted disruption of Hoxb-1 fail to form the motor nucleus of the VIIth nerve. Development. 1996;122:3217–3228. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow JR, Capecchi MR. Targeted disruption of the Hoxb-2 locus in mice interferes with expression of Hoxb-1 and Hoxb-4. Development. 1996;122:3817–3828. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöpperl H, Bienz M, Studer M, Chan S-K, Aparicio S, Brenner S, Mann RS, Krumlauf R. Segmental expression of Hoxb-1 is controlled by a highly conserved autoregulatory loop dependent upon exd/pbx. Cell. 1995;81:1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maconochie MK, Nonchev S, Studer M, Chan S-K, Pöpperl H, Sham MH, Mann RS, Krumlauf R. Cross-regulation in the mouse HoxB complex: the expression of Hoxb2 in rhombomere 4 is regulated by Hoxb1. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1885–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquin TD, Veronique B, Schneider S, Topilko P, Ghilini G, Kato F, Charnay P, Champagnat J. Reorganization of pontine rhythmogenic neuronal networks in Krox-20 knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;17:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: an update. Ped Pulmonol. 1998;26:273–282. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199810)26:4<273::aid-ppul7>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croaker GDH, Shi E, Simpson E, Cartmill T, Cass DT. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and Hirschprung’s disease. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:316–322. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad GG, Mazza NM, Defendini R, Blanc WA, Driscoll JM, Epstein MA, Epstein RA, Mellins RB. Congenital failure of autonomic control of ventilation, gastrointestinal motility, and heart rate. Medicine. 1978;57:517–526. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]