Abstract

Proximal tubular epithelial cells are major sites of homocysteine (Hcy) metabolism and are the primary sites for the accumulation and intoxication of inorganic mercury (Hg2+). Previous in vivo data from our laboratory have demonstrated that mercuric conjugates of Hcy are transported into these cells by unknown mechanisms. Recently, we established that the mercuric conjugate of cysteine [2-amino-3-(2-amino-2-carboxy-ethylsulfanylmercuricsulfanyl)propionic acid; Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys], is transported by the luminal, amino acid transporter, system b0,+. As Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys and the mercuric conjugate of Hcy (2-amino-4-(3-amino-3-carboxy-propylsulfanylmercuricsulfanyl)butyric acid; Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy) are similar structurally, we hypothesized that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy is a substrate for system b0,+. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the saturation kinetics, time dependence, temperature dependence, and substrate specificity of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy transport in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells stably transfected with system b0,+. MDCK cells are good models in which to study this transport because they do not express system b0,+. Uptake of Hg2+ was twofold greater in the transfectants than in wild-type cells. Moreover, the transfectants were more susceptible to the toxic effects of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy than wild-type cells. Accordingly, our data indicate that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy is transported by system b0,+ and that this transporter likely plays a role in the nephropathy induced after exposure to Hg2+. These data are the first to implicate a specific, luminal membrane transporter in the uptake and toxicity of mercuric conjugates of Hcy in any epithelial cell.

In recent years, homocysteine (Hcy) has become known as an amino acid of significant clinical importance.1,2 Normally, Hcy forms from the intracellular metabolism of methionine and is subsequently broken down by one of two pathways: remethylation or transsulfuration. In the remethylation pathway, a methyl group, from either N5-methyltetrahydrofolate or betaine, is transferred to Hcy to reform methionine. Alternatively, Hcy can enter the transsulfuration pathway, where it is broken down into cysteine (Cys) and α-ketobutyrate via the sequential actions of cystathionine-β-synthase and γ-cystathionase.2 Alterations in these metabolic pathways may lead to hyperhomocysteinemia, which can contribute to the induction of cardiovascular disease in some humans.3

A number of studies have implicated the kidney as a major site of Hcy metabolism.1,2,4–7 Although both pathways involved in the metabolism of Hcy (ie, transsulfuration and remethylation) are used by renal epithelial cells,8 the transsulfuration route is the predominant means by which Hcy is degraded in these cells.5,6 Moreover, this degradation occurs primarily in the epithelial cells lining the proximal tubule.5 Although our understanding of Hcy metabolism within proximal tubular cells is advancing, the mechanisms by which Hcy gains entry in the cytosolic compartments of these cells remain unclear.

Interestingly, proximal tubular cells are also the primary sites where inorganic mercury (Hg2+) accumulates and exerts its toxic effects. Because of the strong electrophilic properties of Hg2+, mercuric ions are carried around in the plasma as conjugates of thiol-containing biomolecules. Extracellular thiols that have been implicated in the binding of Hg2+ include Cys and glutathione (GSH). In fact, in vitro data from our laboratory indicate that mercuric conjugates of Cys, particularly in the form of 2-amino-3-(2-amino-2-carboxy-ethylsulfanylmercuricsulfanyl)propionic acid (Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys), are taken up at the luminal plasma membrane of proximal tubular cells by the heterodimeric amino acid transporter, system b0,+.9 This transporter is comprised of a light chain subunit, b0,+AT and a heavy chain subunit, rBAT.10,11 It should be pointed out that system b0,+ is the principal sodium-independent amino acid transporter involved in the luminal absorption of the amino acid cystine along the proximal tubule.10–14 Because of the structural homology between Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys and cystine (Cys-S-S-Cys), we proposed recently that Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys behaves as a molecular mimic of cystine at system b0,+.9

Hcy is a thiol-containing amino acid and is a homologue of Cys. Thus one would expect this amino acid to form linear II coordinate covalent complexes with Hg2+. Indeed, our laboratory has shown indirectly that the mercuric conjugate of Hcy, 2-amino-4-(3-amino-3-carboxy-propylsulfanylmercuricsulfanyl)butyric acid (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy) is transported by proximal tubular cells.15 When Hg2+ was administered intravenously to rats as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, some of the administered Hg2+ was taken up at the luminal plasma membrane of proximal tubular epithelial cells.15 The mechanism(s) for this uptake has/have not yet been defined. However, given that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy is similar structurally to the disulfide amino acid homocystine (Hcy-S-S-Hcy), the participation of luminal amino acid transporters seems to be a logical possibility. Some support for this notion comes in part from in vitro data showing that the transport of Hcy and homocystine in the kidneys is mediated by a high-affinity transporter with a substrate specificity similar to that characterized for the cystine transporter, system b0,+.16 Additional evidence from in vitro studies using retinal pigment epithelial cells indicates that Hcy is a substrate of system b0,+.17 As homocystine and cystine are structural homologues, it is logical, therefore, to postulate that homocystine may be transported by the same amino acid transporter (ie, system b0,+) that facilitates the uptake of cystine and the mercuric conjugate, Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys. Moreover, given the structural similarity between Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys and Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, we hypothesize that system b0,+ can mediate the uptake of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in renal epithelial cells expressing this transport system.

We tested this hypothesis by studying and characterizing the transport of Hg2+, when presented as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, in type II Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells transfected stably with both subunits of system b0,+. These cells are a line of renal epithelial cells derived from the distal nephron of the dog and were used for the current experiments because they do not normally express b0,+AT or rBAT. Data from the present study indicate clearly that Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, is indeed a transportable, toxic substrate of system b0,+. This study is also the first to provide direct molecular evidence for the participation of a specific amino acid transport system, namely system b0,+, in the absorptive transport of, and cellular intoxication by, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Culture

Stably transfected MDCK cells, strain II, expressing both subunits of system, b0,+, b0,+AT, and rBAT (b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants), were kindly provided by Dr. François Verrey (University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland) and were cultured as described previously.9,18 Briefly, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1% essential amino acids, 200 μg/ml geneticin, and 150 μg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Wild-type cells were cultured in the same media without geneticin or hygromycin B. Cells were passaged by dissociation in 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen)/0.5 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in phosphate-buffered saline. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Evaluation of Transport

Uptake measurements were performed as described previously with minor changes.9,19,20 Both, wild-type and transfected MDCK cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells/well and were cultured for 24 hours before the experiment. Transfectants were cultured in the presence of 1 μmol/L dexamethasone to induce the expression of rBAT.18 At the beginning of each experiment, culture media was aspirated and cells were washed with warm uptake buffer (25 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethansulfonic acid (HEPES)/Tris, 140 mmol/L N-methyl-d-glucamine chloride, 5.4 mmol/L KCl, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.8 mmol/L MgSO4, and 5 mmol/L glucose, pH 7.5). Uptake was initiated by adding 250 μl of uptake buffer containing radiolabeled substrates. Cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C, unless otherwise stated. Uptake was terminated by aspiration of radiolabeled compounds followed by the addition of ice-cold uptake buffer containing 1 mmol/L sodium 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), a well-known mercury chelator.21 Cells were washed twice with 2,3-dimercaptopropane-1-sulfonate and were subsequently solubilized with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate in 0.2 N NaOH. The cellular lysate was then added to 5 ml of Opti-Fluor scintillation cocktail (Packard Biosciences, Meriden, CT) and the radioactivity contained therein was determined by counting samples in a Beckman LS6500 scintillation counter (Beckmann Instruments, Fullerton, CA).

Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy was formed by incubating 5 μmol/L HgCl2, containing 203Hg2+, with 20 μmol/L dl-homocysteine (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 10 minutes at room temperature. The ratio of these compounds ensured that each mercuric ion in solution bonded to the sulfur atom of two molecules of the respective thiol in a linear II coordinate covalent manner. The mercuric conjugates of thiol-containing molecules formed under these conditions have been shown to be thermodynamically stable from a pH of 1 to 14.22

Transport of Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, was characterized under various conditions. Time-course experiments were performed wherein both transfectants and wild-type cells were incubated with 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+, for various periods ranging from 5 to 90 minutes. The saturation kinetics for the transport processes were determined by incubating cells with Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+, for 15 minutes at 37°C in the presence of unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (1, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50, 100 μmol/L). The maximum velocity (Vmax) and Michealis-Menten constant (Km) were calculated using the following formula: v = (Vmax × [S])/(Km + [S]), where v = velocity of transport and [S] = substrate concentration. The temperature dependence for the uptake of Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, was assessed by measuring the uptake of Hg2+ at 4°C and 37°C in the presence of unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (1, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50 μmol/L). Substrate specificity for the uptake of Hg2+ was assessed by incubating cells with Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+, for 15 minutes at 37°C in the presence of amino acids that are substrates of system b0,+ (cystine, Hcy, arginine, leucine, histidine, phenylalanine, lysine, or cycloleucine) or amino acids that are not substrates of this system (glutamate or aspartate). With the exception of cystine, all amino acids were used at a concentration of 3 mmol/L. Because of low solubility, the highest attainable concentration of cystine was 1 mmol/L.

As a negative control, cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L Hg2+ in the presence of 20 μmol/L GSH, which promotes the formation of the mercuric conjugate of GSH, G-S-Hg-S-G. Incubation with Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys served as a positive control. These conjugates were formed as described previously for Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. Wild-type and transfected cells were incubated with each conjugate for 30 minutes at 37°C.

To test the ability of Hg2+ to bind to competing thiol-containing molecules, cells were incubated with 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSH (1 to 50 μmol/L). The incubation was performed for 30 minutes at 37°C.

Cystine Efflux Assays

The ability of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy to stimulate the efflux of cystine was measured in wild-type cells and b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants. Cells were exposed to 1 mmol/L cystine, containing [35S]-cystine, for 10 minutes at 37°C. Extracellular cystine was aspirated and the cells were washed with warm uptake buffer. To measure the effects of various compounds on the efflux of [35S]-cystine/Cys (some of the cystine may have been reduced intracellularly), cells were incubated for 1 minute at 37°C with either uptake buffer, 1 mmol/L unlabeled cystine, Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, or homocystine. After this incubation, the extracellular fluid was removed and placed in vials containing 5 ml of Opti-Fluor scintillation cocktail. The [35S] contained therein was measured using standard methods for liquid scintillation spectrometry. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold buffer and were solubilized using 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate/0.2 N NaOH. The cellular content of [35S] was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

Assessment of Cellular Viability

The toxicological effects of Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, were quantified using a methylthiazoletetrazolium (MTT) assay as described previously.9,23 This assay measures the activity of mitochondrial dehydrogenase via the conversion of MTT (Sigma Chemical Co.) to formazan crystals. Wild-type and transfected MDCK cells were seeded at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well culture dishes (200 μl/well). Cells were cultured for 24 hours, washed twice with warm uptake buffer, and then treated with Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (100, 250, 500, 750, or 1000 μmol/L) in uptake buffer containing glutamine. The incubation was performed for 14 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with warm uptake buffer and incubated in MTT (0.5 mg/ml) for 2 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After this incubation, solubilization buffer (10% Triton X-100, 0.1 N HCl in isopropyl alcohol) was added to each well and the mixture was allowed to incubate for 16 hours at room temperature. Each plate was read at 490 nm in a BioTek μQuant spectrophotometric plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Morphologically discernable pathological changes in the transfected and wild-type MDCK II cells exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy were also characterized and semiquantified microscopically. Wild-type and transfected MDCK cells were seeded in chambered coverslips (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL) at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells/ml (0.5 ml/chamber). Cells were treated with various concentrations of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in uptake buffer containing glutamine. This incubation was performed for 14 hours at 37°C. After the exposure to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, cells were washed with buffer and the culture media was returned to the chamber. Microscopic images were captured immediately using an Olympus IX-70 inverted biological microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with Normarsky optics (Nikon, Melville, NY). All observations of cells were performed using ×10 eyepieces and a ×20 planfluor objective. Images were captured with a Nikon DXM 1200 digital camera.

Data Analysis

All transport experiments were repeated at least three times and each measurement was performed in quadruplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SE. Data expressed as a percent were first normalized using the arcsine transformation before applying any parametric statistical analysis. This transformation takes the arcsine of the square root of the decimal fraction of the percent score. Data for each parameter assessed were first analyzed for normality and for homogeneity of variance. After determining that the data for each parameter were distributed normally with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and that there was equal variance among the groups of data using the Levene’s test, the means for each set of data were evaluated with a two-way analysis of variance. When statistically significant F-values were obtained with the analysis of variance, Tukey’s multiple comparison posthoc procedure was used to assess differences among the means. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Transport of Hg2+ (as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy)

Time-course analyses show that there was time-dependent uptake of Hg2+ in both the wild-type cells and the b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants exposed to 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (Figure 1A). However, with the exception of the 5-minute time point, the level of uptake of Hg2+ in the transfectants was significantly greater than that of the wild-type cells at all times studied.

Figure 1-4242.

Uptake of inorganic mercury (Hg2+) in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells exposed to 5 μmol/L Hg2+, as a mercuric conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy). A: Cells were exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, at 37°C, for time periods ranging from 5 to 90 minutes. Samples were collected at indicated times. B: The saturation kinetics of the transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy were measured by incubating cells for 15 minutes at 37°C with 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+, in the presence of unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (1 to 100 μmol/L). Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at the initial time point or concentration. ++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding time points or concentrations. +++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding time points or concentrations. ++++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding time points. +++++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding time points.

The saturation kinetics for the uptake of Hg2+ during the exposure to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy were analyzed in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected cells (Figure 1B). Concentration-dependent uptake of Hg2+ during the exposure to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy was significantly greater in the b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants than in the wild-type cells. In the transfectants, the estimated Vmax for transport was 60.8 ± 7.0 pmol × mg protein−1 × minute−1, whereas the Km was calculated to be 144.4 ± 24.8 μmol/L.

Temperature-dependent uptake of Hg2+ was detected only in the b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (Figure 2). At 37°C, the uptake of Hg2+, as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, was significantly greater in the transfectants than in the corresponding groups of wild-type cells. Furthermore, the amount of transport in the transfectants at 37°C was significantly greater than that observed at 4°C. When the experimental temperature was maintained at 4°C, the association of Hg2+ with either cell type was minimal. There were no significant differences in the accumulation of Hg2+ between corresponding groups of transfected and wild-type cells. Moreover, the amount of substrate associated with either cell type at 4°C was similar to that associated with wild-type cells at 37°C.

Figure 2-4242.

Temperature dependence of the uptake of inorganic mercury (Hg2+), as a conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells. Cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+ in the presence of unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (1 to 50 μmol/L), for 30 minutes at 37°C or 4°C. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the means for the corresponding groups of wild-type cells at 4°C and 37°C and significantly different from the mean for the corresponding group of transfected cells at 4°C. +, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants at the initial concentration at 37°C. ++, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants at each of the preceding concentrations at 37°C. +++, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants at each of the preceding concentrations at 37°C. ++++, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants at each of the preceding concentrations at 37°C. +++++, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants at each of the preceding concentrations at 37°C.

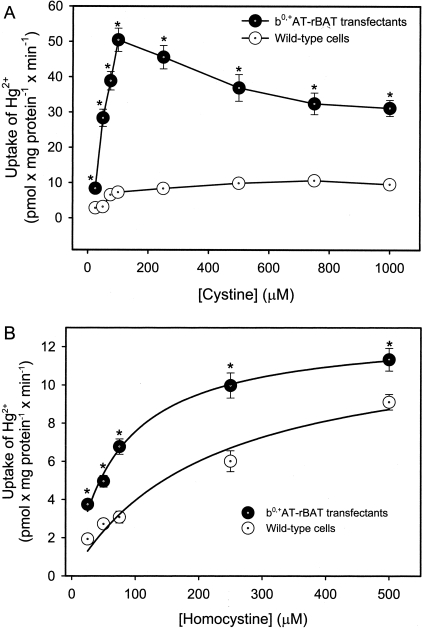

The findings obtained in the substrate specificity experiments for the transport of Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, are presented in Figure 3. In the transfected MDCK II cells exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, the uptake of Hg2+ was reduced significantly by the presence of unlabeled Hcy, arginine, leucine, histidine, phenylalanine, lysine, or cycloleucine. The amino acids, glutamate and aspartate, which are not substrates of system b0,+, did not significantly alter the transport of Hg2+. Interestingly, co-incubation of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy with unlabeled cystine resulted in a twofold increase in the uptake of Hg2+ in the transfected MDCK cells. This stimulation was also observed at lower concentrations of cystine (Figure 4A). Similarly, when the transport of Hg2+ was measured in the presence of excess homocystine, uptake of Hg2+ was stimulated (Figure 4B). Interestingly, this stimulation occurred in both wild-type and transfected cells.

Figure 3-4242.

Substrate specificity analyses of the uptake of inorganic mercury (Hg2+) in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells. Cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C with 5 μmol/L Hg2+, as a conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), in the presence of various unlabeled amino acids (3 mmol/L; unlabeled cystine = 1 mmol/L). Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the control group of the corresponding cell type.

Figure 4-4242.

Uptake of inorganic mercury (Hg2+), as a conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), in the presence of unlabeled cystine (A) (1 to 1000 μmol/L) or unlabeled homocystine (B) (1 to 500 μmol/L) in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells.

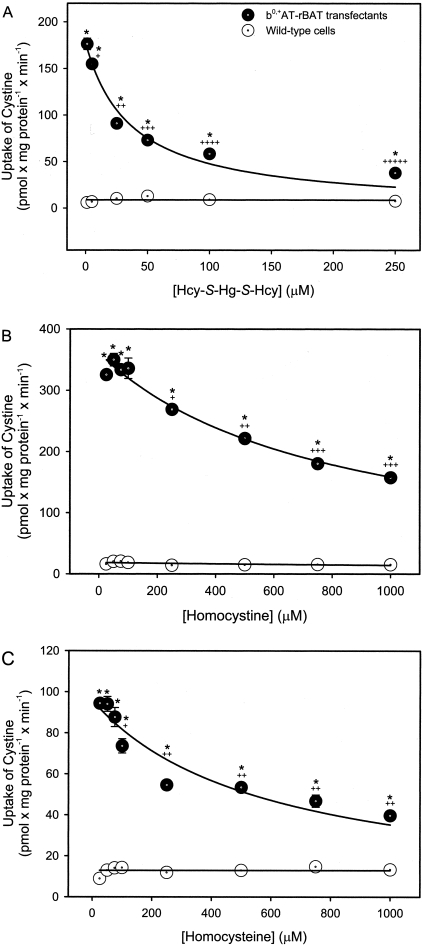

Alternatively, when the uptake of [35S]-cystine was measured in the presence of excess Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, transport in the b0,+AT-rBAT-transfectants was inhibited (Figure 5A). The IC50 (50% inhibition) for this process was calculated to be 37.2 ± 7.9 μmol/L. There were no significant differences among groups of wild-type cells. The uptake of other substrates for system b0,+, ie, [3H]-arginine or [3H]-lysine, was also inhibited by the presence of excess Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (data not shown). Furthermore, incubation with increasing concentrations of homocystine (Figure 5B) or Hcy (Figure 5C) inhibited the uptake of [35S]-cystine in the transfectants in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 5-4242.

Uptake of cystine in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells. Cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L cystine, containing 35S-cystine, in the presence of unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (A), homocystine (B), or Hcy (C) for 15 minutes at 37°C. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at the initial concentration. ++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations. +++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations. ++++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations. +++++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations.

Efflux Assays

Efflux assays were performed in wild-type cells and b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants to determine the ability of unlabeled cystine, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys, or homocystine to stimulate the efflux of [35S]-cystine (Figure 6A). Cells were preloaded with [35S]-cystine for 10 minutes at 37°C, after which the efflux of [35S] (the radiolabel may be in the form of cystine or Cys as some intracellular reduction may occur) was measured for 1 minute at 37°C in the presence of the aforementioned compounds. There were no significant differences in the efflux of cystine among the treatment groups of wild-type cells. In the transfectants, however, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys, homocystine, and cystine stimulated the efflux of [35S]. The efflux of [35S] was greatest when cells were treated with Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys (369.7 ± 25 nmol × mg−1 × minute−1) or Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (364.4 ± 20.7 nmol × mg−1 × minute−1). This efflux was significantly greater than that in corresponding cells exposed to cystine (215.3 ± 8.8 nmol × mg−1 × minute−1) or homocystine (260.9 ± 9.2 nmol × mg−1 × minute−1). The efflux of [35S] was significantly lower when the extracellular fluid consisted only of uptake buffer (119.2 ± 16.2 nmol × mg−1 × minute−1). When the cellular content of [35S] was measured, the pattern of cystine uptake corresponded inversely to the pattern of cystine efflux described above, ie, the greater the efflux, the lower the cellular content of [35S] (Figure 6B).

Figure 6-4242.

Efflux of [35S] (A) and cellular content of [35S] after efflux (B) in wild-type MDCK II cells and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfectants. Cells were exposed to 1 mmol/L cystine, containing 35S-cystine, for 10 minutes at 37°C and were subsequently incubated with buffer only, 1 mmol/L cystine, homocystine, or mercuric conjugates of Cys (Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys) or Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy) for 1 minute at 37°C. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in triplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the group of transfectants exposed to buffer. ++, Significantly different from the mean for the transfectants exposed to buffer, cystine, or homocystine. +++, Significantly different from the mean for all other groups of transfected cells.

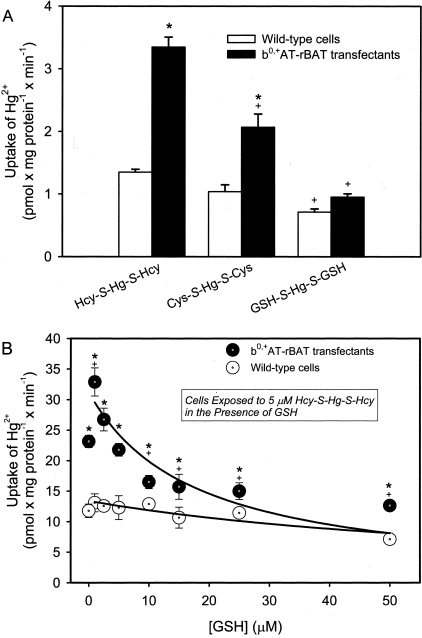

Transport of Mercuric Conjugates of Thiol-Containing Biological Molecules

The uptake of Hg2+, as a mercuric conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), Cys (Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys), or GSH (G-S-Hg-S-G) was measured in wild-type cells and transfectants (Figure 7A). When the transfected cells were exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, the uptake of Hg2+ was threefold greater than that in the corresponding group of wild-type cells. Incubation with Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys resulted in a twofold increase in the uptake of Hg2+ compared with that in the corresponding group of wild-type cells. When the cells were exposed to G-S-Hg-S-G, there were no significant differences in the uptake of Hg2+ between corresponding groups of wild-type and transfected MDCK II cells. These data confirmed previously reported findings.9

Figure 7-4242.

Uptake of inorganic mercury (Hg2+) in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells. A: Cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L Hg2+ as a conjugate of 20 μmol/L Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), Cys (Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys), or GSH (G-S-Hg-S-G) for 30 minutes at 37°C. B: Cells were exposed to 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, containing 203Hg2+, for 30 minutes at 37°C in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSH. Results are presented as mean ± SE. Data represent three experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the corresponding group of transfected cells treated with Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy (A) or significantly different from the mean of the same cell type at the initial concentration of GSH (B).

Thiol Competition Assays

Thiol competition assays were performed to determine whether GSH was able to compete with Hcy to bind Hg2+. The formation of G-S-Hg-S-G was measured indirectly by incubating wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected cells with Hg2+, as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, in the presence of increasing concentrations of GSH. As the GSH concentration increased, the amount of Hg2+ taken up by the transfectants was reduced significantly. There were no significant differences in the accumulation of Hg2+ among groups of wild-type cells (Figure 7B).

Cellular Viability Assays

To determine the relationship between cellular transport and intoxication, the cellular viability of wild-type and transfected cells exposed to Hg2+ was assessed. After a 14-hour exposure to 50 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, the viability of the b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants was reduced by 12%; exposure to 1 mmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy decreased viability by 85% (Figure 8). The cellular viability of the wild-type cells was decreased significantly (20%) only after exposure to 1 mmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. Treatment with 5 μmol/L Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy for 30 minutes (experimental conditions used to study various characteristics of transport) did not significantly reduce the cellular viability in either cell type (data not shown).

Figure 8-4242.

Cellular viability of wild-type MDCK II cells and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfectants after a 14-hour treatment with various concentrations of inorganic mercury (Hg2+), as a conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy). Results are presented as percent control. Data represent two experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, Significantly different (P < 0.05) from the mean for the corresponding group of wild-type cells. +, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at the initial concentration. ++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations. +++, Significantly different from the mean for the same cell type at each of the preceding concentrations.

Morphological Assessment of Toxicity

The appearance of pathological changes was documented in wild-type and transfected cells exposed to various concentrations of Hg2+, as Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. After a 14-hour exposure to 500 μmol/L Hg2+, the wild-type cells were confluent and exhibited few discernable morphological changes (Figure 9). In contrast, after the Hg2+-exposure, the transfected cells were no longer confluent and many of the cells appeared spherical as they lost their attachments to the culture surface (Figure 9). In addition, many cells contained large vacuoles and exhibited fragmented DNA.

Figure 9-4242.

Morphological analysis of wild-type (A) and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected (B) MDCK II cells exposed to 500 μmol/L inorganic mercury (Hg2+), as a conjugate of Hcy (Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy), for 14 hours at 37°C. All observations of cells were performed using ×10 eyepieces and a ×20 planfluor objective. Images are representative of two separate experiments.

Discussion

Inorganic mercury (Hg2+) binds readily to thiol-containing biomolecules, such as GSH, Cys, and Hcy. These three thiols are present in plasma at similar concentrations (5 to 10 μmol/L) and thus, may each bind Hg2+. Indeed, GSH and Cys have been implicated in the binding and subsequent transport of Hg2+.21 Moreover, Cannon and colleagues24,25 have proposed that mercuric conjugates of Cys (Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys), which are similar structurally to the amino acid cystine, are taken up by cystine transporters via a mechanism of molecular mimicry. It is thought that Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys acts as a mimic of cystine at the site of these carriers. In fact, recent data from our laboratory indicate that, indeed, the cystine transporter, system b0,+, is involved in the luminal uptake of Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys in proximal tubular cells.9

Although Hcy and Cys are in plasma at similar concentrations,26 very little is known about the potential role of Hcy in the renal uptake of Hg2+. Given that Hcy is a structural homologue of Cys, it seems logical to hypothesize that this amino acid is involved in the handling and transport of Hg2+ in the kidneys. In fact, previous in vivo data from our laboratory provided the first line of experimental evidence implicating Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy as a transportable substrate along the renal proximal tubule.15 The actual mechanism(s) involved in this uptake, however, was/were not defined. Consequently, we tested the hypothesis that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, in addition to Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys, is a transportable substrate of system b0,+. We did this by characterizing the transport and toxicity of Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, in type II MDCK cells that were or were not stably transfected with both subunits of system b0,+, ie, b0,+AT and rBAT. The b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected cells have been characterized previously and have been shown to be a reliable in vitro model in which to study system b0,+-mediated transport.9,18

Time-course analyses of the transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected cells revealed that the rate of uptake of this conjugate in the transfectants was at least twofold greater than that in the wild-type cells. Analysis of the saturation kinetics for the transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy also showed a twofold increase in the magnitude of uptake of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in the transfectants compared with that in wild-type cells. Because the only apparent difference between the wild-type and transfected MDCK cells was the presence of a functional system b0,+ transporter, it can be concluded that this transporter was responsible for the differences in transport between the two cell types studied. As a result, the findings obtained from the transfected cells indicate that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy is indeed a transportable substrate of system b0,+ and that this transporter is capable of mediating the absorptive uptake of this conjugate in vivo.

It should be mentioned that a small amount of Hg2+ was associated with the wild-type cells when the cells were exposed to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. It is likely, however, that this association represents nonspecific binding and/or uptake via another mechanism. This conclusion is supported by our data showing temperature-dependent transport in only the transfectants. These data support the hypothesis that the uptake Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy in the transfectants is a carrier-mediated process.

Substrate-specificity analyses of transport provide further support for the hypothesis that Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy is taken up by system b0,+. Substrates that are typically transported by system b0,+ inhibited the transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy whereas amino acids that are not substrates of this transporter did not affect the uptake of this conjugate. This pattern of inhibition parallels that observed when cystine9,18 or Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys,9 were used as transportable substrates of system b0,+.

Interestingly, when the uptake of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy was assessed in the presence of unlabeled cystine or homocystine, inward transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy was stimulated twofold or greater in the transfected cells. This stimulation was observed at all concentrations of cystine or homocystine studied. This phenomenon was specific for the substrate Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy because the transport of other substrates of system b0,+, such as [35S]-cystine, [3H]-arginine, or [3H]-lysine was inhibited when each of these substrates was co-administered with unlabeled cystine or homocystine. One explanation for the observed stimulatory effect is that the presence of excess cystine or homocystine increases the rate of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy uptake by some presently unknown exchange mechanism.

To test this theory, we studied the efflux of [35S]-cystine/Cys (as some of the cystine may be reduced intracellularly) in wild-type and b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK cells pre-exposed to 1 mmol/L cystine, containing [35S]-cystine. Subsequent incubation with unlabeled Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys, cystine, or homocystine induced the efflux of [35S] from the b0,+AT-rBAT transfectants. Of the compounds tested, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy and Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys appeared to have the greatest effect on the efflux of [35S]. Cystine and homocystine were also able to stimulate efflux, but to a lesser degree. The efflux of [35S] from cells exposed to uptake buffer was significantly less than that in the cells exposed to other compounds. This efflux may represent the fraction of cystine that diffuses passively out of the cells. Although the implications for these data are unclear, the results indicate that there is a unique interaction between Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy and cystine, which promotes the uptake of this conjugate. A similar type of interaction has been shown to occur when Cys-S-Hg-S-Cys was used as a transportable substrate of system b0,+.9

Pathophysiological measurements, in the form of MTT assays, and detailed microscopic analyses from the present study indicate that the amino acid transporter, system b0,+, plays a role in the cellular intoxication induced by exposure to Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. Data from the MTT assays and morphological analyses indicate that cells transfected with system b0,+ undergo cellular pathology and death after exposure to lower concentrations of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy than do corresponding wild-type cells. These data and the current transport data indicate that a strong relationship exists between the rates of transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy by system b0,+ and the induction of cellular injury and death. Therefore, it appears that system b0,+ participates in the cellular intoxication induced by Hg2+ by promoting the uptake of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy. The intracellular mechanisms involved in the induction of renal cellular injury and death remain undefined.

Thiol competition experiments were performed to test indirectly the phenomenon of thiol exchange. The electrophilic properties of Hg2+ are such that this metal binds readily to thiol-containing molecules.21 The idea of thiol competition would imply that mercuric ions bind preferentially to the most prevalent thiol.27 Indeed, the current data suggest that as the concentration of excess thiol (in this case, GSH) increases, the formation of mercuric conjugates of that thiol (G-S-Hg-S-G) is favored even when Hg2+ exists initially as a conjugate of Hcy. This phenomenon of thiol competition would be predicted to occur in cases of hyperhomocysteinemia, in which elevated concentrations of plasma Hcy (as high as 200 μmol/L)28,29 would promote the preferential formation of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy after exposure to Hg2+. Because this conjugate is a highly transportable species of Hg2+, hyperhomocysteinemia may increase the risk of renal injury after exposure to this toxic metal. Interestingly, in vivo studies in rats have shown that acute hyperhomocysteinemia results in a fourfold increase in the renal uptake of Hcy.6 Therefore, hyperhomocysteinemia not only favors the formation of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, but also may potentially up-regulate the uptake of Hcy. Given that this conjugate and the amino acid Hcy are both transportable substrates of system b0,+, we can speculate that the probable up-regulation of this system, as may be the case under hyperhomocysteinemic conditions, would not only promote the uptake of Hcy, but also that of a toxic species of Hg2+, Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy.

In conclusion, the results from the current study demonstrate for the first time that Hg2+, in the form of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy, is a transportable substrate of system b0,+. Accordingly, this system may play a role in the nephropathy induced after exposure to Hg2+. These results also implicate a mechanism of molecular mimicry whereby Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy mimics the amino acid cystine or homocystine at the site of system b0,+ to gain access to the intracellular compartment of renal epithelial cells. The data provide strong evidence for the involvement of the Na+-independent transporter, system b0,+, in the absorptive transport of Hcy-S-Hg-S-Hcy at the luminal plasma membrane of proximal tubular cells. However, this transporter is likely not the sole mechanism responsible for this transport. Previous studies in isolated perfused renal tubules have provided strong evidence for the involvement of at least one Na+-dependent transport system.25 Additional studies are clearly needed to provide a more complete understanding of the mechanisms by which Hg2+ is transported across the luminal plasma membranes of proximal tubular epithelial cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Delon Barfuss at Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, for his assistance with the manufacture of the 203Hg; Dr. François Verrey at the University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, for kindly providing the b0,+AT-rBAT-transfected MDCK II cells; and Ms. Jamie Battle for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Rudolfs K. Zalups, Mercer University School of Medicine, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, 1550 College St., Macon, GA 31207. E-mail: zalups_rk@mercer.edu.

Supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Environmental Health Services grants, ES05980, ES05157, and ES11288, to R.K.Z. and ES012556 to C.C.B.), and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award to C.C.B. ES012556 is the NRSA awarded to C.C.B.

References

- Refsum H, Ueland PM, Nygard O, Vollset SE. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:31–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selhub J. Homocysteine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Daly L, Robinson K, Naughten E, Cahalane S, Fowler B, Graham I. Hyperhomocysteineimia: an independent risk factor for vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1149–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudman NP, Guo XW, Gordon RB, Dawson PA, Wilcken DE. Human homocysteine catabolism: three major pathways and their relevance to development of arterial occlusive disease. J Nutr. 1996;126:295S–300S. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.suppl_4.1295S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JD, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. Characterization of homocysteine metabolism in the rat kidney. Biochem J. 1997;328:287–292. doi: 10.1042/bj3280287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JD, Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. Renal uptake and excretion of homocysteine in rats with acute hyperhomocysteinemia. Kidney Int. 1998;54:601–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostom A, Brosnan JT, Hall B, Nadeau MR, Selhub J. Net uptake of plasma homocysteine by the rat kidney in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 1995;116:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AN, Bostom AG, Selhub J, Levey AS, Rosenberg IH. The kidney and homocysteine metabolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2181–2189. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12102181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Bauch C, Verrey F, Zalups RK. Mercuric conjugates of cysteine are transported by the amino acid transporter, system b0,+: implications of molecular mimicry. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:663–673. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000113553.62380.F5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J, Zorzano A. Molecular biology of plasma membrane amino acid transporters. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:969–1054. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacin M, Fernandez E, Chilaron J, Zorzano A. The amino acid transporter system b0,+ and cystinuria. Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Stelzner MG, Lee WS, Wells RG, Brown D, Hediger MA. Expression of mRNA (D2) encoding a protein involved in amino acid transport in S3 proximal tubule. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:F1087–F1092. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.263.6.F1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furriols M, Chillaron J, Mora C, Castello A, Bertran J, Camps M, Testar X, Vilaro S, Zorzano A, Palacin M. rBat, related to L-cystine transport, is localized to the microvilli of proximal straight tubules, and its expression is regulated in kidney by development. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:27060–27068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer R, Loffing J, Rossier G, Bauch C, Meier C, Eggermann T, Loffing-Cueni D, Kuhn LC, Verrey F. Luminal heterodimeric amino acid transporter defective in cystinuria. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4135–4147. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK, Barfuss DW. Participation of mercuric conjugates of cysteine, homocysteine, and N-acetylcysteine in mechanisms involved in the renal tubular uptake of inorganic mercury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:551–561. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V94551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman JW, Wald H, Blumberg G, Pepe LM, Segal S. Homocystine uptake in isolated rat renal cortical tubules. Metabolism. 1982;31:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naggar H, Fei YJ, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Regulation of reduced-folate transporter-1 (RFT-1) by homocysteine and identity of transport systems for homocysteine uptake in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauch C, Verrey F. Apical heterodimeric cystine and cationic amino acid transporter expressed in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol. 2003;283:F181–F189. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00212.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Kekuda R, Wang H, Prasad PD, Mehta P, Huang W, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Structure, function, and regulation of human cystine/glutamate transporter in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;42:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Ola S, Prasad PD, El-Sherbeny A, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Regulation of taurine transporter expression by NO in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2000;281:C1825–C1836. [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK. Molecular interactions with mercury in the kidney. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:113–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhr B, Rabenstein DL. Nuclear magnetic-resonance studies of solution chemistry of metal-complexes 9 Binding of cadmium, zinc, lead, and mercury by glutathione. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:6944–6950. doi: 10.1021/ja00802a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslamkhan AG, Han YH, Yang XP, Zalups RK, Pritchard JB. Human renal organic anion transporter 1-dependent uptake and toxicity of mercuric-thiol conjugates in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:590–596. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon VT, Barfuss DW, Zalups RK. Molecular homology and the luminal transport of Hg2+ in the renal proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:394–402. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon VT, Zalups RK, Barfuss DW. Amino acid transporters involved in luminal transport of mercuric conjugates of cysteine in rabbit proximal tubule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:780–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueland PM, Refsum H, Stabler SP, Malinow MR, Andersson A, Allen RH. Total homocysteine in plasma or serum Methods and clinical applications. Clin Chem. 1993;39:1764–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabenstein DL, Fairhurst MT. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the solution chemistry of metal complexes XI The binding of methylmercury by sulfhydryl-containing amino acids and by glutathione. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:2086–2092. doi: 10.1021/ja00841a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SP, Marcell PD, Podell ER, Allen RH, Savage DG, Lindenbaum J. Elevation of total homocysteine in the serum of patients with cobalamin or folate deficiency detected by capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:466–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI113343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow MR. Hyperhomocysteinemia: a common and easily reversible risk factor of occlusive artherosclerosis. Circulation. 1990;81:2004–2006. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.6.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]