Abstract

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM) consist of clusters of abnormally dilated blood vessels. Hemorrhaging of these lesions can cause seizures and lethal stroke. Three loci are associated with autosomal dominant CCM, and the causative genes have been identified for CCM1 and CCM2. We have generated mice with a targeted mutation of the Ccm1 gene, but an initial survey of 20 heterozygous mice failed to detect any cavernous malformations. To test the hypothesis that growth of cavernous malformations depends on somatic loss of heterozygosity at the Ccm1 locus, we bred animals that were heterozygous for the Ccm1 mutation and homozygous for loss of the tumor suppressor Trp53 (p53), which has been shown to increase the rate of somatic mutation. We observed vascular lesions in the brains of 55% of the double-mutant animals but none in littermates with other genotypes. Although the genetic evidence suggested somatic mutation of the wild-type Ccm1 allele, we were unable to demonstrate loss of heterozygosity by molecular methods. An alternative explanation is that p53 plays a direct role in formation of the vascular malformations. The striking similarity of the human and mouse lesions indicates that the Ccm1+/− Trp53−/− mice are an appropriate animal model of CCM.

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM, OMIM no. 116860) are vascular abnormalities consisting of clusters of greatly dilated thin-walled vessels.1,2 The dilated vessels are lined by a single layer of endothelial cells and lack smooth muscle. Typically, normal cerebral parenchyma does not penetrate the lesion. Instead, connective tissue surrounds the vessels so that the lesion forms a mass distinct from the surrounding parenchyma. Cavernous malformations can form in any part of the central nervous system, and some patients with CCM also have cutaneous vascular malformations.3 Hemorrhaging of the vessels in a cavernous malformation can result in headaches, seizures, and stroke, that are sometimes lethal.

Three loci have been linked to autosomal dominant CCM,4–7 and the genes responsible for CCM18,9 and CCM210,11 have been identified. Both KRIT1 (the protein product of CCM1) and Malcavernin (product of CCM2) may be involved in integrin signaling.10,12,13 Mutations in CCM1 include deletions and point mutations throughout the KRIT1 protein, but all seem to result in frame-shifts and premature truncation of the protein. The few predicted missense mutations have been shown to affect mRNA splicing instead.14–16 This allelic series suggests that the phenotype is because of loss of function of the KRIT1 protein.

The focal nature of the randomly scattered lesions, together with the observation that patients with inherited CCM are more likely to have multiple lesions than patients with sporadic cases of the disease,2 has led to the suggestion that formation of cavernous malformations requires somatic loss of the wild-type allele. In the sporadic cases of CCM, two independent somatic mutations would be required in the same cell, whereas in inherited CCM, only one somatic mutation would be required. The alternative to this two-hit model is simply that heterozygosity for CCM1 mutations results in haploinsufficiency and disease.

We have generated mice with a targeted mutation of Ccm1 and previously described the phenotype of homozygous mutants.17 Complete loss of Ccm1 is embryonic lethal, and the phenotype suggests a primary defect in arterial morphogenesis. Gene expression analyses indicated that during development, Ccm1 is required in an arterial-specific pathway involving Notch4. This observation suggests that despite their appearance, cavernous malformations are derived from defective arteries, not veins. Here, we describe the phenotype of the heterozygous mutant mice and present evidence that loss of the tumor suppressor Trp53 (p53) predisposes mice to development of vascular malformations.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of B6;129-Ccm1tm1Dmar mice has been previously described.17 B6.129S2-Trp53tm1Tyj mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). In our laboratory, the Trp53tm1Tyj line was maintained by continued backcrossing of heterozygotes to C57BL/6J mice. To generate the double-mutant mice, Ccm1tm1Dmar/+ (Ccm1+/−) heterozygotes from generation N3 and N5 of the C57BL/6J backcross were crossed to Trp53tm1Tyj/+ (Trp53+/−) heterozygotes. In the second generation, compound heterozygotes were crossed to Ccm1+/+ Trp53+/− littermates. Because most Trp53−/− homozygotes develop tumors and die by 6 months of age,18,19 all F2 mice were euthanized by CO2 between 3 and 4 months of age. All mouse experiments were performed with approval of the Duke University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Genotyping

DNA was isolated from tail biopsies by proteinase K digestion, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for genotyping Ccm1tm1Dmar mice have been described previously.17 Primers for genotyping Trp53tm1Tyj mice were 5′-TGACTCCAGCCTAGACTGATGTTG (intron 6, forward), 5′-CCTGTCATACTTTGTTAAGAAGGG (PGK-polyA, forward), and 5′-GTGATGATGGTAAGGATAGGTCGG (exon 7, reverse).

Tissue Processing and Histological Staining

All brains were fixed in buffered formalin by immersion so that small blood vessels would not be distorted by perfusion and so that they could be more easily identified by the presence of red blood cells. After fixation overnight at 4°C, the brains were cut into 2-mm coronal slices using an acrylic brain matrix (Electron Microscopy Services, Washington, PA). Any visible vascular lesions were photographed with a Coolpix 995 digital camera (Nikon, Melville, NY) attached to a dissecting microscope. The coronal slices were embedded in paraffin wax and cut into 5-μm sections on a Microm HM325 microtome (Microm International, Walldorf, Germany). The sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and examined stained (bright field) or unstained (dark field) with an Olympus BX41 microscope (Olympus America, Melville, NY).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed using Harris-modified hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific) and alcoholic eosin, yellowish (Fisher Scientific). Masson trichrome staining was performed by the Duke University histopathology core facility. Sections were photographed with a Cool Snap Pro digital camera (Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ) attached to an Olympus BX41 microscope.

Immunofluorescence

Sections were deparaffinized in Citrisolv (Fisher Scientific) and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the slides in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate. After antigen retrieval, the slides were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4. Before incubation with the primary antibody, each section was blocked with 1 ml of 10% normal goat serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) in PBS for 1 hour. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against von Willibrand’s Factor (G9269; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), laminin (L9393; Sigma-Aldrich), and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA) were diluted according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Sections were incubated for 1 hour in 1 ml of primary antibody diluted in PBS plus 2.5% goat serum. Sections were then washed three times with 1 ml of PBS. Fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was diluted in 1 ml of PBS plus 2.5% goat serum, and sections were incubated for 1 hour in the dark. After secondary incubation, the slides were washed in PBS, and coverslips were mounted with Prolong anti-fade reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Microdissection and Mutation Detection in Mouse Lesions

Laser capture microdissection of hematoxylin-stained sections was performed using an Autopix LCM system (Arcturus Bioscience, Mountain View, CA). Isolated tissue was digested using the Picopure DNA extraction kit (Arcturus Bioscience) and used as template in PCR. Because of the small amount of template, PCR amplification of the tetranucleotide microsatellite required two rounds of 40 cycles each with nested primers. In the second round of amplification, one of the primers was labeled with 32P. The primers for the first round of amplification were 5′-CAAACATGTTCCAGGTATCCTGTG and 5′-GGCAGGCAGATTTCTGAGTTCGAG. The primers for the second round of PCR were 5′-TCCTGTGACAAGAATGGATCCCAG and 5′-GAGGCCAGCCTGGTCTACAGAGTG. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis through a 6% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography.

Mutation Detection in Human TP53

Sections of cavernous malformations from patients with known mutations in CCM1 were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained with 0.1% methyl green for 5 minutes. After rinsing, the lesions were scraped up with a scalpel blade while the section was viewed under a dissecting microscope. Dissected material was digested in 15 to 50 μl of proteinase K digestion buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% Tween-20, 1 mg/ml proteinase K) for 48 hours at 55°C, with the addition of 1 μl of 50 mg/ml proteinase K after the first 24 hours. The digest was then heated to 95°C for 20 minutes, and used as template in PCR reactions. The primers used to amplify coding exons of TP53 were designed using the Primer 3 program (http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primers/primer3_www.cgi). Primer sequences and PCR amplification conditions are available on request. Gel-purified PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and run on an ABI Prism 3730 sequencer (Perkin Elmer, Wellesley, MA). Data were analyzed using Sequencher software version 4.1.4 (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI) by comparison to a reference sequence (GenBank, NM_000546).

Results

No Vascular Lesions in Ccm1+/− Heterozygotes

As previously described, homozygosity for the knockout allele Ccm1tm1Dmar (hereafter indicated Ccm1−/−) is lethal at midgestation.17 Although the embryos have clear vascular abnormalities, the central nervous system is insufficiently developed to support formation of a vascular lesion that could be classified as a mature cavernous malformation. Because CCM1 is an autosomal dominant disease in humans, we expected that heterozygous knockout mice would be the appropriate model for the disease. For an initial survey, we examined the brains of 20 heterozygous mice for the presence of cavernous malformations. The mice ranged in age from 8 weeks to 14 months and were from generations F1 to N3 of a C57BL/6J backcross. All 20 brains were cut into 2-mm-thick coronal slices and examined with a dissecting microscope. A subset of 10 brains, chosen at random, were embedded and completely sectioned. No cavernous malformations were observed.

Identification of Vascular Lesions in Ccm1+/− Trp53−/− Double Mutants

To test the two-hit model genetically, we used a two generation intercross to generate mice that were heterozygous for the Ccm1 mutation and homozygous for loss of the tumor suppressor gene Trp53 (p53) (see Materials and Methods). Analysis of fibroblasts isolated from homozygous Trp53−/− mice has shown an increase in the rate of somatic mutation, including deletions, mitotic recombination, and chromosome loss.20 We hypothesized that these molecular events might lead to an increased incidence of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the hemizygous Ccm1 locus, and lead to the development of vascular lesions.

In the second generation of the intercross, vascular lesions bearing many of the hallmarks of cavernous malformations were found in five of nine animals with the genotype Ccm1+/− Trp53−/− (Table 1). No vascular lesions were found in littermates with other genotypes; three of the five vascular lesions were easily identified on the surface of the brain or in the 2-mm coronal slices (Figure 1; A, C, and E), but no lesions were observed in 42 littermates that were examined in the same way. Additionally, 10 Ccm1+/+ Trp53−/− and 3 Ccm1+/−Trp53+/− brains were fully sectioned without revealing any vascular lesions. These results indicate that the vascular lesions are not solely because of loss of Trp53, nor are they because of modifier effects of any 129 alleles derived from the embryonic stem cells that might become homozygous as a result of the intercross. No gross lesions were observed on cursory examination of the other internal organs. Because cutaneous vascular lesions have been reported in some human CCM patients,3 we flayed several Ccm1+/−Trp53−/− animals and examined the underside of the skin. No vascular lesions were visible.

Table 1.

Frequency of Vascular Malformations in Mice with Mutations in Ccm1 and Trp53

| Genotype

|

Total number of brains | 2-mm slices | 5-μm sections | Number of malformations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ccm1 | Trp53 | ||||

| +/− | −/− | 9 | 9 | 9 | 5 |

| +/+ | −/− | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| +/− | +/+ | 29* | 29 | 10† | 0 |

| +/− | +/− | 23 | 23 | 3 | 0 |

Includes 20 animals from C57BL/6J backcross.

Sectioned brains are from C57BL6J backcross.

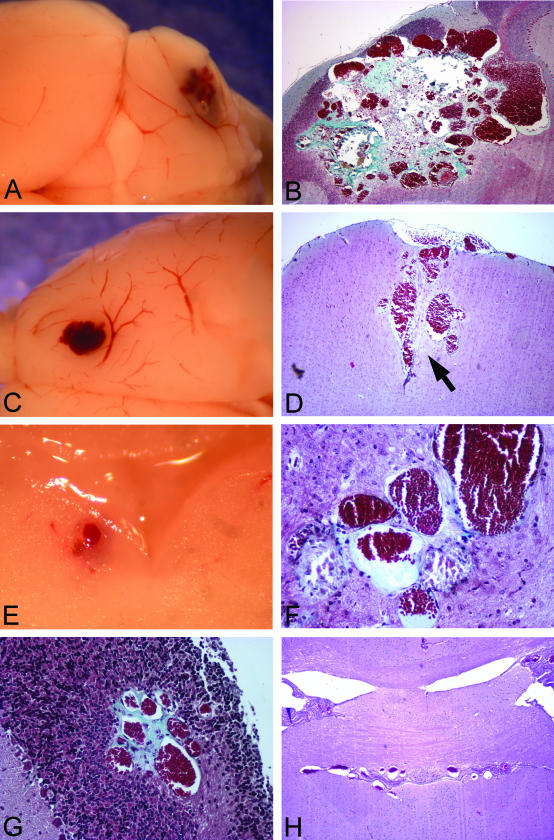

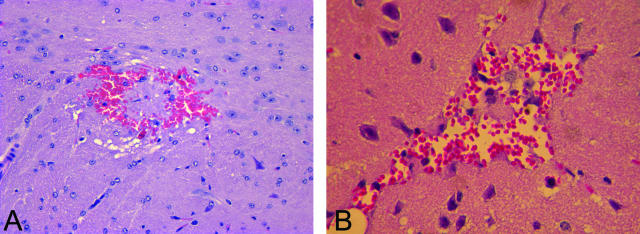

Figure 1.

General appearance of vascular malformations in Ccm1+/− Trp53−/− mice. The mouse lesions consist of grossly dilated, clustered vessels. In some cases, vessels are surrounded by collagen deposits (blue stain, B, F, G). A: Lesion 1, cerebellum. B: Lesion 1. Masson trichrome stain. C: Lesion 2, motor cortex. D: Lesion 2. Masson trichrome stain. E: Lesion 3, adjacent to fourth ventricle. F: Lesion 3. Masson trichrome stain. G: Lesion 4, cerebellum. Masson trichrome stain. H: Lesion 5, third ventricle. H&E stain. Original magnifications: ×40 (B, D, H); ×200 (F, G).

Characterization of Vascular Lesions

The histological characteristics of the vascular malformations on H&E staining differed between animals to some extent, but all featured ectatic, thin-walled blood vessels that resembled modestly to markedly dilated capillaries (Figure 1). Most had walls composed of endothelial cells and had minimal collagenous material. In general, brain parenchyma was entrapped between the abnormal blood vessels (Figure 1D, arrow), but in some lesions the vessels abutted one another (Figure 1F). These histological features overlap with classical examples of the three common, nonarterial, human cerebrovascular malformations: cavernous malformation, venous malformation, and capillary telangiectasia. Most of the vessels resembled the ectatic capillaries of capillary telangiectasia, and the intervening brain tissue had minimal reactive changes in these cases. Other vessels, however, were markedly dilated; these were generally isolated vessels or just a few vessels together, resembling so-called venous malformations. Occasional lesions had more collagenized, closely apposed vessels, along with mineralization and evidence of remote hemorrhage, suggestive of cavernous malformation (see below and Figure 4). These had reactive changes, such as gliosis, in the adjacent brain. In the largest lesion, different regions had varying appearances, with areas resembling each of the three human malformation types (Figure 1B). The lesions were found in several brain regions: cerebellum, motor cortex, third ventricle, and adjacent to the fourth ventricle. The mouse with the lesion of the third ventricle (Figure 1H) was found dead in the cage, but none of the other animals had an overt phenotype (eg, ataxia, lethargy, seizures) before dissection.

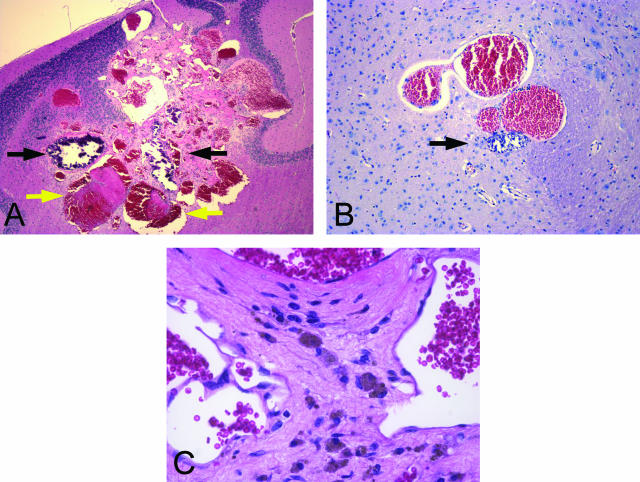

Figure 4.

Thrombosis, calcification, and hemosiderin deposits are visible within lesions. In these H&E-stained sections, thrombi (yellow arrows) appear pink, whereas calcifications (black arrows) stain dark blue. Hemosiderin is visible as brownish pigment within the cytoplasm of macrophages (C). A: Lesion 1. B: Lesion 3. C: Lesion 1. Original magnifications: ×40 (A); ×100 (B); ×400 (C).

Masson trichrome staining revealed that, as in cavernous malformations, the blood vessels within several of the mouse lesions were surrounded by connective tissue rather than brain parenchyma (Figure 1; B, F, and G). Staining with antisera against von Willibrand’s factor confirmed that the vessels were lined with a single layer of endothelium, and endothelial cells were not present in the intervening tissue (Figure 2A). The histological appearance of the lesions, together with these immunohistochemical results, rules out hemangiosarcoma, which has been reported in a subset of Trp53 knockout mice.18,19

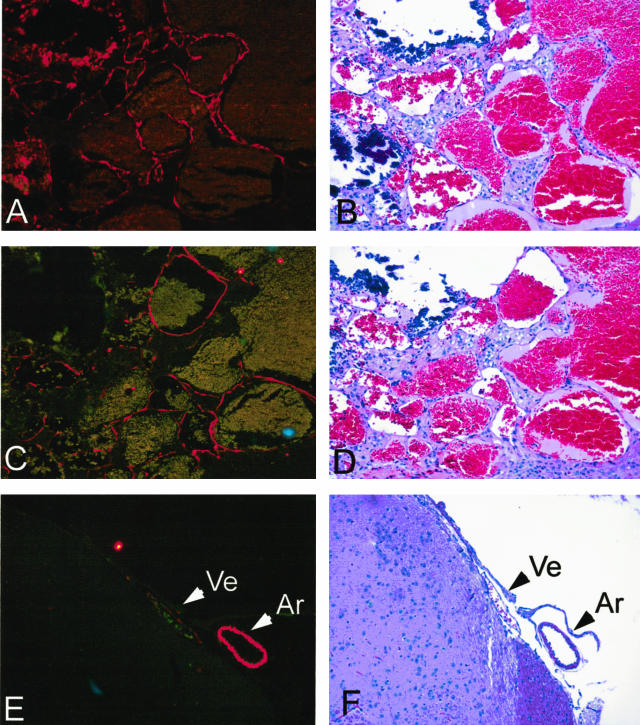

Figure 2.

Vessels within lesions are lined by a single layer of endothelium and lack a muscular wall. A: Lesion 1 stained with anti-Von Willibrand’s factor antibody. B: H&E stain of adjacent section. C: Lesion 1 stained with anti-α-SMA. D: H&E stain of adjacent section. E: Normal artery and vein from same brain stained with anti-α-SMA. F: H&E stain of normal artery and vein. Ar, artery; Ve, vein. Original magnifications, ×200.

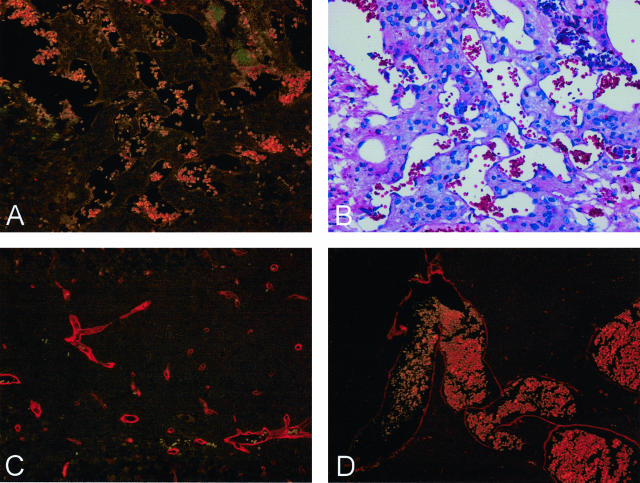

Although the vessels comprising cavernous malformations express SMA,21–23 they lack the muscular walls of arteries. Staining with antibodies against SMA demonstrated that the vessels within a mouse lesion expressed SMA at levels intermediate between a vein and an artery of similar size and that the lesion vessels did not appear to posses muscular walls (Figure 2C). Expression of laminin was variable in the mouse lesions. In the largest lesion, many of the vessels completely lacked laminin (Figure 3A), although it was expressed in normal vessels of the surrounding brain parenchyma (Figure 3C). In contrast, vessels in several of the smaller lesions appeared to express laminin normally (eg, Figure 3D). The published data on laminin expression in human cavernous malformations is similarly inconsistent. Kilic and colleagues22 observed laminin expression, whereas Rothbart and colleagues23 concluded that laminin was absent from cavernous malformations.

Figure 3.

Some vessels within lesions fail to express laminin. A: Lesion 1 stained with anti-laminin. B: H&E stain of adjacent section. C: Normal capillaries close to lesion 1 stained with anti-laminin. D: Lesion 2 stained with anti-laminin. Original magnifications: ×200 (A–C); ×100 (D).

Cavernous malformations often contain regions of thrombosis and/or calcification, together with macrophages containing hemosiderin. Both calcified vessels and thrombi were observed in several of the mouse lesions (Figure 4, A and B), and at higher magnification, hemosiderin-filled macrophages could be identified by their shape and color (Figure 4C).

In one Ccm1+/−Trp53−/− animal, a small, irregular fresh hemorrhage was observed (Figure 5A) indicating ongoing hemorrhagic events in these animals. As indicated above, no cavernous malformations were observed in the original C57BL6/J backcross, but an irregular blood vessel was observed in a 10-month-old F1 heterozygote (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Microhemorrhage and irregular blood vessels in brains of Ccm1+/− mice may be an early stage in growth of a cavernous malformation. A: Ccm1+/−Trp53−/−, H&E. B: B6;129-Ccm1+/− F1, H&E. Original magnifications: ×200 (A); ×∼300 (B).

Testing for LOH in a Mouse CCM

The genetic evidence from the intercross is consistent with the two-hit hypothesis and an increase in the somatic mutation rate in the Trp53−/− mice, but confirmation requires detection of LOH at the Ccm1 locus. The Ccm1 mutation was produced in R1 embryonic stem cells (strain 129) and then backcrossed to inbred strain C57BL/6J (B6). The Trp53 mutation was also inbred on a B6 background. Thus, at the Ccm1 locus, heterozygous animals will have one mutant 129 allele and one wild-type B6 allele. LOH would be indicated by loss of the wild-type B6 allele. The closest linked polymorphic microsatellite to the Ccm1 gene is a polymorphic tetranucleotide repeat mapping ∼90 kb downstream of Ccm1. As an initial test for LOH using this microsatellite, we microdissected the largest lesion (Figure 1, A and B) using a scalpel blade to remove the lesion from a slide while it was viewed under a dissecting microscope. PCR of DNA isolated from the lesion tissue showed no loss of the B6 allele (data not shown).

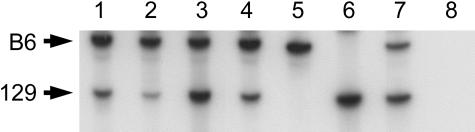

Although this initial test proved negative, we realized that the vascular lesion is a complex mixture of different cell types, only one of which may harbor the initial LOH event. To more precisely test the different cell types in and around the lesion, we used laser capture microscopy to isolate material from the same lesion. Within the lesion, we separately isolated vascular endothelium and the interstitial tissue surrounding the vessels. Because it is possible that Ccm1 is not normally expressed in endothelial cells,24,25 we also captured a sample of the brain parenchyma immediately flanking the lesion. Both the 129 and B6 alleles amplified from all laser capture samples, indicating that the wild-type Ccm1 allele has not been lost by mitotic recombination or by a large deletion (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Analysis of a tetra-nucleotide microsatellite linked to Ccm1 shows no evidence of LOH in a mouse lesion. No loss of the wild-type C57BL/6J allele is observed in several tissue samples isolated from lesion 1 by laser capture microdissection. Lane 1, normal cerebellar parenchyma from the opposite hemisphere; lane 2, cerebellar parenchyma flanking the lesion; lane 3, vascular endothelium from the lesion; lane 4, interstitial tissue from the lesion; lane 5, C57BL/6J DNA; lane 6, 129×1/SvJ DNA; lane 7, Ccm1+/− DNA; lane 8, water control.

No TP53 Mutations in Human CCMs

To test the possibility that the intercross has serendipitously uncovered a direct role for p53 in formation of cavernous malformations, we tested human cavernous malformations for mutations in TP53, the human ortholog of Trp53. DNA was extracted from three independent lesions from two different families with known mutations in CCM1. One of the samples was sequenced for 9 of the 10 coding exons of TP53. The other two samples were sequenced for exons 4 to 8 where the majority of previously reported mutations have been found. No mutations in TP53 were identified.

Discussion

The mouse vascular malformations described in this study are remarkably similar in appearance to human vascular malformations, particularly to cavernous malformations. Both the mouse lesions and human cavernous malformations consist of grossly dilated vessels with a single layer of endothelium and hyalinized walls. Both contain hemosiderin deposits and regions of thrombosis and calcification, indicative of chronic, ongoing hemorrhage. In the best-developed mouse lesions, collagen fills the space between blood vessels as is seen in human cavernous malformations. In other lesions, apparently normal brain parenchyma surrounds the vessels, a characteristic more typical of capillary telangiectasias than cavernous malformations.1 The largest lesion (Figure 1B) contains regions resembling both types of malformation. Significantly, both cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasias have been observed in the same human patients, and some cavernous malformations contain regions that resemble telangiectasias, suggesting that the two lesions may represent slightly different manifestations of the same disease.26

It is possible that the different histological appearances within a single lesion, both in mice and in humans, represent different stages in the formation of the final lesion. The irregular blood vessel found in a Ccm1+/− mouse (Figure 5B) is particularly interesting because it may represent a very early stage in development of a cavernous malformation. The smaller mouse lesions with features of capillary telangiectasia (Figure 1) may be intermediate stages. It is possible that if these lesions were allowed to mature further in aged mice, they would more closely resemble classical human cavernous malformations. In contrast to the 3- to 4-month life span of these mice, human cavernous malformations most likely grow for many years before clinical presentation. Unfortunately, the frequency of malignancies in older Trp53−/− mice precludes aging the mice much beyond the period at which these animals were analyzed.

The data on laminin expression in human and mouse malformations is intriguing. Given the variability of expression in the mouse malformations, and the disagreement between different groups who have analyzed human lesions,22,23 it is possible that loss of laminin expression is a secondary event that occurs later in the formation of a CCM. If that is the case, only the most developed cavernous malformations would lack laminin expression.

Although the presence of vascular malformations in Ccm1+/−Trp53−/− mice is consistent with the two-hit model, we have been unable to confirm it by DNA analysis. Although we cannot rule out the possibility of somatic point mutations or microdeletions, our results indicate that the vascular malformations in Ccm1+/−Trp53−/− mice are not associated with LOH caused by the chromosome-wide events that have been described in Trp53−/− mice.20

It remains unclear whether Ccm1 is expressed in mature vasculature. Although expression is ubiquitous in mid-gestation mouse embryos, in situ hybridization of adult brain sections shows expression in neurons with little, if any, expression in vascular endothelium24,25 In contrast, an antibody raised against a KRIT1 peptide cross-reacted with endothelial cells and astrocytes, as well as neurons, in sections of human brain.27 It is possible that cavernous malformations result from defective cell-cell signaling between vascular endothelial cells and the neurons or astrocytes of the surrounding cerebral parenchyma. Because of this uncertainty, we analyzed both vascular endothelium and brain parenchyma surrounding the lesions. We did not, however, separately isolate neurons and astrocytes.

An alternative explanation for our results is that the KRIT1 and p53 proteins both play a role in regulation of vascular growth and interact, either directly or indirectly, to form cavernous malformations. Support for this hypothesis comes from other interaction partners of KRIT1 and from the recent identification of the CCM2 protein, Malcavernin.10,11 KRIT1 has been shown to interact with ICAP1 (Itgb1bp1),12,13 which binds to both β1 integrin and the Rac1 GTPase.28 In vascular smooth muscle cells, the response to mechanical stress involves signaling from β1 integrin to Rac, resulting in activation of p38 MAP kinase, which in turn activates p53.29 Malcavernin (also known as OSM) has been shown to function as a scaffold protein, linking Rac to downstream kinases in the p38 pathway.30 If similar signaling pathways are involved in formation of cavernous malformations, both KRIT1 and Malcavernin may indirectly regulate p53 activity.

It is interesting to note that infection of newborn rats with polyoma virus can induce a variety of cerebrovascular lesions that resemble cavernous malformations, capillary telangiectasias, and hemangiosarcomas.31 Given the ability of polyoma virus to block p53 activity,32 this result may be additional evidence for the involvement of p53 in formation of cavernous malformations. However, our analysis of three human cavernous malformations with mutations in KRIT1 failed to detect any mutations in TP53, suggesting that formation of cavernous malformations does not necessarily require somatic mutation of TP53. The lack of vascular malformations in the Ccm1+/+ p53−/− mice indicates that loss of p53 alone is insufficient to induce cavernous malformations.

Because CCMs occur in the central nervous system, access to tissue samples is restricted to autopsy specimens and a few surgically resected lesions. Studies aimed at understanding the progression of these lesions are limited to noninvasive procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging. The identification of an animal model that reliably recapitulates many features of the human disease will contribute to our ability to study the progression and pathophysiology of these vascular lesions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric W. Johnson for human CCM sections, and Martha Hanes and Mark Becher for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Douglas Marchuk, Ph.D., Box 3175, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710. E-mail: march004@mc.duke.edu.

Supported by the American Heart Association (Burgher Foundation award 0070028N to D.A.M.) and the National Institutes of Health (postdoctoral National Research Service Award 5F32NS011133 to N.W.P.).

References

- Zabramski JM, Henn JS, Coons S. Pathology of cerebral vascular malformations. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1999;10:395–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarity JL, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. The natural history of cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1999;10:411–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eerola I, Plate KH, Spiegel R, Boon LM, Mulliken JB, Vikkula M. KRIT1 is mutated in hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation associated with cerebral capillary malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1351–1355. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchuk DA, Gallione CJ, Morrison LA, Clericuzio CL, Hart BL, Kosofsky BE, Louis DN, Gusella JF, Davis LE, Prenger VL. A locus for cerebral cavernous malformations maps to chromosome 7q in two families. Genomics. 1995;28:311–314. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubovsky J, Zabramski JM, Kurth J, Spetzler RF, Rich SS, Orr HT, Weber JL. A gene responsible for cavernous malformations of the brain maps to chromosome 7q. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:453–458. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunel M, Awad IA, Anson J, Lifton RP. Mapping a gene causing cerebral cavernous malformation to 7q11.2-q21. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6620–6624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig H, Gunel M, Cepeda O, Johnson E, Ptacek L, Steinberg G, Ogilvy C, Berg M, Crawford S, Scott R, Steichen-Gersdorf E, Sabroe R, Kennedy C, Mettler G, Beis M, Fryer A, Awad I, Lifton R. Multilocus linkage identifies two new loci for a mendelian form of stroke, cerebral cavernous malformation, at 7p15-13 and 3q25.2-27. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1851–1858. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.12.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge-le Couteulx S, Jung HH, Labauge P, Houtteville JP, Lescoat C, Cecillon M, Marechal E, Joutel A, Bach JF, Tournier-Lasserve E. Truncating mutations in CCM1, encoding KRIT1, cause hereditary cavernous angiomas. Nat Genet. 1999;23:189–193. doi: 10.1038/13815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo T, Johnson EW, Thomas JW, Kuehl PM, Jones TL, Dokken CG, Touchman JW, Gallione CJ, Lee-Lin SQ, Kosofsky B, Kurth JH, Louis DN, Mettler G, Morrison L, Gil-Nagel A, Rich SS, Zabramski JM, Boguski MS, Green ED, Marchuk DA. Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a Krev-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2325–2333. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liquori CL, Berg MJ, Siegel AM, Huang E, Zawistowski JS, Stoffer T, Verlaan D, Balogun F, Hughes L, Leedom TP, Plummer NW, Cannella M, Maglione V, Squitieri F, Johnson EW, Rouleau GA, Ptacek L, Marchuk DA. Mutations in a gene encoding a novel protein containing a phosphotyrosine-binding domain cause type 2 cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1459–1464. doi: 10.1086/380314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denier C, Goutagny S, Labauge P, Krivosic V, Arnoult M, Cousin A, Benabid AL, Comoy J, Frerebeau P, Gilbert B, Houtteville JP, Jan M, Lapierre F, Loiseau H, Menei P, Mercier P, Moreau JJ, Nivelon-Chevallier A, Parker F, Redondo AM, Scarabin JM, Tremoulet M, Zerah M, Maciazek J, Tournier-Lasserve E. Mutations within the MGC4607 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:326–337. doi: 10.1086/381718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawistowski JS, Serebriiskii IG, Lee MF, Golemis EA, Marchuk DA. KRIT1 association with the integrin-binding protein ICAP-1: a new direction in the elucidation of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1) pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:389–396. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D, Chang DD, Dietz HC. Interaction between krit1 and icap1α infers perturbation of integrin beta1-mediated angiogenesis in the pathogenesis of cerebral cavernous malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2953–2960. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.25.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave-Riant F, Denier C, Labauge P, Cecillon M, Maciazek J, Joutel A, Laberge-Le Couteulx S, Tournier-Lasserve E. Spectrum and expression analysis of KRIT1 mutations in 121 consecutive and unrelated patients with cerebral cavernous malformations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:733–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurans MS, DiLuna ML, Shin D, Niazi F, Voorhees JR, Nelson-Williams C, Johnson EW, Siegel AM, Steinberg GK, Berg MJ, Scott RM, Tedeschi G, Enevoldson TP, Anson J, Rouleau GA, Ogilvy C, Awad IA, Lifton RP, Gunel M. Mutational analysis of 206 families with cavernous malformations. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:38–43. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.1.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verlaan DJ, Siegel AM, Rouleau GA. Krit1 missense mutations lead to splicing errors in cerebral cavernous malformation. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1564–1567. doi: 10.1086/340604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead KJ, Plummer NW, Adams JA, Marchuk DA, Li DY. Ccm1 is required for arterial morphogenesis: implications for the etiology of human cavernous malformations. Development. 2004;131:1437–1448. doi: 10.1242/dev.01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C, Deng L, Henegariu O, Liang L, Stambrook PJ, Tischfield JA. Chromosome instability contributes to loss of heterozygosity in mice lacking p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7405–7410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoya K, Asai A, Sasaki T, Kimura K, Kirino T. Expression of smooth muscle proteins in cavernous and arteriovenous malformations. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102:257–263. doi: 10.1007/s004010100362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic T, Pamir MN, Kullu S, Eren F, Ozek MM, Black PM. Expression of structural proteins and angiogenic factors in cerebrovascular anomalies. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1172–1191. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200005000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart D, Awad IA, Lee J, Kim J, Harbaugh R, Criscuolo GR. Expression of angiogenic factors and structural proteins in central nervous system vascular malformations. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:915–924. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denier C, Gasc JM, Chapon F, Domenga V, Lescoat C, Joutel A, Tournier-Lasserve E. Krit1/cerebral cavernous malformation 1 mRNA is preferentially expressed in neurons and epithelial cells in embryo and adult. Mech Dev. 2002;117:363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Wilda M, Braun VM, Richter HP, Hameister H. Mutation and expression analysis of the KRIT1 gene associated with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Acta Neuropathol. 2002;104:231–240. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigamonti D, Johnson PC, Spetzler RF, Hadley MN, Drayer BP. Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:60–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Amankulor NM, Voorhees J, Luleci G, Lifton RP, Gunel M. KRIT1/cerebral cavernous malformation 1 protein localizes to vascular endothelium, astrocytes, and pyramidal cells of the adult human cerebral cortex. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:943–949. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000114512.59624.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degani S, Balzac F, Brancaccio M, Guazzone S, Retta SF, Silengo L, Eva A, Tarone G. The integrin cytoplasmic domain-associated protein ICAP-1 binds and regulates Rho family GTPases during cell spreading. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:377–388. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig F, Mayr M, Xu Q. Mechanical stretch-induced apoptosis in smooth muscle cells is mediated by β1-integrin signaling pathways. Hypertension. 2003;41:903–911. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000062882.42265.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlik MT, Abell AN, Johnson NL, Sun W, Cuevas BD, Lobel-Rice KE, Horne EA, Dell’Acqua ML, Johnson GL. Rac-MEKK3-MKK3 scaffolding for p38 MAPK activation during hyperosmotic shock. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ncb1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flocks JS, Weis TP, Kleinman DC, Kirsten WH. Dose-response studies to polyoma virus in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1965;35:259–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Wiman KG. Polyoma virus middle T and small T antigens cooperate to antagonize p53-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]