Abstract

Growth arrest DNA damage-inducible gene 45 β (GADD45β) has been known to regulate cell growth, apoptotic cell death, and cellular response to DNA damage. Down-regulation of GADD45β has been verified to be specific in hepatocellular cancer (HCC) and consistent with the p53 mutant, and degree of malignancy of HCC. This observation was further confirmed by eight HCC cell lines and paired human normal and HCC tumor tissues by Northern blot and immunohistochemistry. To better understand the transcription regulation, we cloned and characterized the active promoter region of GADD45β in luciferase-expressing vector. Using the luciferase assay, three nuclear factor-κB binding sites, one E2F-1 binding site, and one putative inhibition region were identified in the proximal promoter of GADD45β from −865/+6. Of interest, no marked putative binding sites could be identified in the inhibition region between −520/−470, which corresponds to CpG-rich region. The demethylating agent 5-Aza-dC was used and demonstrated restoration of the GADD45β expression in HepG2 in a dose-dependent manner. The methylation status in the promoter was further examined in one normal liver cell, eight HCC cell lines, eight HCC tissues, and five corresponding nonneoplastic liver tissues. Methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction and sequencing of the sodium bisulfite-treated DNA from HCC cell lines and HCC samples revealed a high percentage of hypermethylation of the CpG islands. Comparatively, the five nonneoplastic correspondent liver tissues demonstrated very low levels of methylation. To further understand the functional role of GADD45β under-expression in HCC the GADD45β cDNA constructed plasmid was transfected into HepG2 (p53 WT) and Hep3B (p53 null) cells. The transforming growth factor-β was assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which revealed a decrease to 40% in transfectant of HepG2, but no significant change in Hep3B transfectant. Whereas, Hep3B co-transfected with p53 and GADD45β demonstrated significantly reduced transforming growth factor-β. The colony formation was further examined and revealed a decrease in HepG2-GADD45β transfectant and Hep3B-p53/GADD45β co-transfectant. These findings suggested that methylation might play a crucial role in the epigenetic regulation of GADD45β in hepatocyte transformation that may be directed by p53 status. Thus, our results provided a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanism of GADD45β down-regulation in HCC.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers in many parts of the world including the Far East, the southern Sahara, and southern Europe. It accounts for nearly half a million deaths worldwide.1 Despite recent advances in diagnostic and therapeutic management, prognosis of HCC remains poor. Recent epidemiological data suggests that the incidence of HCC is increasing in the United States, with the rate of new cases at 17,300 per year.2

Three members of the GADD45 gene family, GADD45α, GADD45β, and GADD45γ, have been identified based on the extensive region of conserved sequence. All of them can be induced by DNA damage and/or other environmental stresses.3,4 GADD45β was first identified as a myeloid differentiation primary response gene activated in murine myeloid leukemia cells (M1) by interleukin-6 after induction of terminal differentiation. GADD45β has been implicated in regulating cell growth, apoptotic cell death, and cellular responses to DNA damage. As a positive apoptosis modulator, activation of GADD45β prevents the propagation of damaged cells, causing cell growth arrest and subsequent apoptosis after exposure to genotoxins.5

From our previous study, we used the DNA microarray to compare the gene expression profile of HCC tissues with that of matched nonneoplastic tissues. We identified that the expression of GADD45β was significantly down-regulated in HCC. The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses of 85 HCC cases confirmed the significant and specific GADD45β decrease in HCC. Moreover, down-regulation of GADD45β was strongly correlated with HCC differentiation and advanced nuclear grade.6 Our results suggested that the lack of GADD45β expression in HCC might lead to the failure of inhibition of atypical cell growth or apoptosis. Understanding the regulation of GADD45β may reveal the relationship between the process of DNA damage repair and hepatocarcinogenesis.

It has been reported that GADD45β can be induced by p53, or growth inhibitory cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.7,8 The TGF-β-dependent apoptotic pathway is important in the elimination of damaged cells. The proximal promoter of GADD45β is activated by TGF-β through the action of Smad 2, Smad 3, and Smad 4. Expression of GADD45β in AML 12 murine hepatocytes has been shown to induce p38 and trigger apoptosis. Whereas, inhibition of GADD45β expression by anti-sense blocks TGF-β-dependent p53 activation and apoptosis. However, it was known that the hepatoma cell line possesses complex regulation mechanisms such as p53 mutation-dependent or -independent pathway, MAPK or JNK/ERK involve TGF-β-mediated apoptosis, and so forth.7,8 In this study, we focus on understanding the mechanism of down-regulation of GADD45β. Our result suggests p53-directed methylation of GADD45β may play a role in HCC cell lines and human tissues.

Materials and Methods

Cell Line and Tissues

The human HCC cell lines HepG2, Hep3B, and normal embryonic liver cell CL-48 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD. Other human HCC cell lines SMMC-7721, BEL-7402, BEL-7404, EBL-7405, QGY-7701, and QGY-7703 were purchased from Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences as described previously.9–11 All tumor cell lines were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium or RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% P/S (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Five pairs of fresh microdissected HCCs and corresponding nonneoplastic liver tissues were retrieved from the surgical pathology files at City of Hope National Medical Center and St. Vincent Hospital. Two fresh HCC tissues with nuclear grade 4 and one fresh HCC tissue with nuclear grade 1 were also included in this profile as the differentiation control. The tissues were examined to confirm the diagnosis and tumor type. Total RNA and genomic DNA were isolated according to the following methods. Procurement of samples was done under institutional human subjects’ guidelines and the applicable laws to protect the privacy of patients.

GADD45β Expression Analyses

Northern blot and IHC study were used to examine the expression of GADD45β from the HCC cell lines and tissues. Total RNA and genomic DNA were isolated using the Rneasy mini kit and the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was tested by running a 1.2% diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)/MOPS agarose gel and the concentration was measured by UV spectroscopy. RNA was stored in DEPC water with 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol and Rnasin (1 U/ml) at −70°C. The 32P-GADD45β probe and blot conditions were the same as previously described.6 The 222-bp probe, including exon 3 of GADD45β, was generated by reverse transcriptase (RT-PCR) from HepG2 total RNA with the following primers: 5′-GGACCCAGACAGCGTGGTCCTCTG-3′ (sense primer, GADD45β +247) and 5′-GTGACCAGGAGACAATGCAGGTCT-3′ (anti-sense primer, GADD45β +445). The SuperScript one-step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for PCR with the following conditions: 1 cycle at 50°C for 30 minutes; 1 cycle at 94°C for 2 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes. The probe was then purified and cleaned using the Gel Extract and Purification kit (Qiagen) and labeled with 32P using the random priming probe kit from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). RNA was electrophoresed in a 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gel, blotted to a Hybond-N membrane (Amersham, Arlington, IL), and UV-cross-linked. The blots were hybridized for 1 hour at 68°C, washed twice with 2× standard saline citrate/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at room temperature and twice with 0.1× standard saline citrate/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 60°C. After hybridization, membranes were exposed for 18 hours and then scanned by a phosphorimager. Quantitative analysis was performed using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) version 5.0 with GAPDH as a loading control. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

In the IHC study, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and blocked in 1:20 normal horse serum. The primary goat anti-human polyclonal GADD45β antibody (200 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and the biotinylated anti-goat IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame CA) were used as the first and the second antibody. Then, after 45 minutes of incubation with AB Complex (Vector Elite kit, 1:200 dilution; Vector Laboratories), diaminobenzidine [0.05 g diaminobenzidine and 100 μl of 30% H2O2 in 100 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)], and 1% copper sulfate were applied for 5 and 10 minutes, respectively. Each slide was counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. For all IHC studies, PBS was used as a negative control. Granular cytoplasmic stain was accessed as positive.

Construction of Luciferase Reporter GADD45β Proximal Promoter Deletion Plasmids

Proximal promoter fragments of GADD45β, spanning −865 to + 6, were cloned upstream of the luciferase gene in the pGL3 basic luciferase expression plasmid (Promega, Madison WI). Six different GADD45β promoter deletion fragments were generated by PCR with GADD45β sense primers: 5′-GGTGAAGCTTGATGTGTATTGGGCTCTTA-3′ (starting at −865), 5′-GAAAGGTACCAGGGGCTGGGGTCGT-3′ (−744), 5′-GGGAAAGCTTCGGTCCGGGACT-3′ (−618), 5′-TTTTAAGCTTTTCTGGCATTCGC-3′ (−470), 5′-GTTCAAGCTTATAAAAGTCGGT-3′ (−273), 5′-CCGAAAGCTTTGGACGAGCGCTCTA-3′ (−123), and an anti-sense primer to + 6 (5′-TATCCTCGCCAAGGACTTTGC-3′). PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 15 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 seconds, 60°C for 40 seconds, 72°C for 2 minutes; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes. HepG2 genomic DNA was used as the PCR template as previously described.6 PCR products were purified and cleaned using Gel Extract and Purification kit (Qiagen) and then inserted into the pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fragments were then digested from the pDrive using HindIII and inserted into the pGL3 basic vector. Another set of primers were used for the PCR to generate detailed proximal promoter fragments of GADD45β from −618 to −273: the sense primers were 5′-CGGAGGTACCGGGGATTCCAGGCCCCCCCGA-3′ (−591), 5′-CTCGGGTACCGGAAATCCCGCGCGCGCCCGA-3′ (−547), 5′-CCCCGGTACCGCGGCTCGGCTGCCGGGAA-3′ (−520), 5′-CGGCGGTACCGCGCCCTCCTCCCGGTT-3′ (−436), 5′-GCCCGGTACCGCCGCTCCTCCCCCTCCCCTCCG-3′ (−391), 5′-CGCAGGTACCGCTGCACTCGCCCTT-3′ (−348), 5′-CAATGGTACCGGCGAATGACTCCA-3′ (−314), and anti-sense primer to + 6 (5′-CTTCCTCGAGCATGTTGCAATTATAATCCAC-3′). A KpnI site was incorporated into the sense primers and a XhoI site into the anti-sense primer. PCR reactions were performed as above. PCR products were digested by KpnI and XhoI and cleaned by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Fragments were then cloned into the corresponding sites of the pGL3 basic plasmid and sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transfection of Reporter Plasmids and Luciferase Assay

Logarithmically growing HepG2 and CL-48 cells (1 × 106) were transfected with 15 μg of pGL3 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid and 7.5 μg of pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (Promega), which served as an internal control for transfection efficiency. pGL3 basic plasmids, pGL3 enhancer plasmids, and pGL3 promoter plasmids were used for negative and positive controls. Cells were transfected by electroporation in a 4-mm gap cuvette (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) for 80 μs at a voltage of 600 V. Forty-eight hours after electroporation, cells were washed with PBS and harvested by scraping directly into 0.9 ml of reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Protein concentration was measured using the Bio-Rad Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The luciferase activity in 20-μl aliquots of cell lysates was measured by luminometry using luciferase reagent (Promega) and β-galactosidase activity was determined using a β-galactosidase assay system (Promega). Promoter activation was determined as the luciferase activity relative to the control after normalizing to β-galactosidase activity.

Cell Treatment with 5-Aza-dC

The day before 5-Aza-dC (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) treatment, logarithmically growing cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per 10-cm cell culture dish and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. On the second day, cells were treated with freshly prepared 5-Aza-dC (10 μmol/L, 50 μmol/L, 100 μmol/L). Forty-eight hours after treatment, the media was removed and cells were washed with PBS. Fresh medium was added, and the cells were incubated for another 48 hours before isolating total cellular RNA and genomic DNA. Total RNA was isolated using the Rneasy mini kit (Qiagen). Running a 1.2% DEPC/MOPS agarose gel tested RNA quality and the concentration was measured by UV spectroscopy. RNA was stored in DEPC water with 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol and Rnasin (1 U/ml) at −70°C. The GADD45β expression was examined by Northern blot as mentioned above.

Methylation-Specific PCR (MSP)

To examine the possibility that lack of GADD45β expression in HCC is associated with hypermethylation of the CpG islands in promoter, MSP was used to locate the hypermethylation area in GADD45β promoter. After the sodium bisulfite treatment, unmethylated cytosine would convert to uracil, but not methylated cytosines.12 Consequently, uracil would be recognized as thymidine by the Taq polymerase in PCR reaction. Sodium bisulfite-treated DNA (1.0 μg) was used to the MSP amplification using the following primers: the methylation-specific sense primer 5′-TTCGAAAGTTCGGGTCGTTTCGCGC-3′ and anti-sense primer 5′-GGGGACCGAATAAATAACCGCG-3′, which included nucleotides corresponding to potentially methylated Cs; the primers for amplification of unmethylated DNA: sense 5′-AAAGTTTGGGTTGTTTTGTGT-3′ and anti-sense 5′-ACCAAATAAATAACCACA-3′, which included the nucleotides corresponding to C nucleotides changed to T in sense primer and A in anti-sense primer. The genomic DNAs were isolated using QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.6 For lowering the cross reaction, the annealing temperatures were designed for a 65°C methylation-specific reaction and a 45°C unmethylated reaction. The methylation-specific and unmethylated DNA-specific primers yielded 137-bp and 128-bp PCR products, respectively, both of which covered the third nuclear factor (NF)-κB binding site and the putative inhibition region. The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 seconds, 60°C (in methylated MSP), or 45°C (in unmethylated MSP) for 40 seconds, 72°C for 2 minutes; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes.

Sequencing of Sodium Bisulfite-Treated DNA

Genomic DNA (1.0 μg) from the HCC cell lines and tissues was denatured at 42°C for 20 minutes with 2 μl of herring sperm DNA and 5.5 μl of fresh 3 mol/L NaOH for a final volume of 50 μl. Six hundred μl of 4 mol/L bisulfite/10 mmol/L hydroquinone solution (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to the reaction system. The system was then incubated at 50°C for 16 hours in the dark. The product was cleaned up using a DNA purification kit (Qiagen). Sodium bisulfite-treated DNA was subjected to PCR using the following primers: 5′-TATTTTTAGTAGAATTTGGGAAAGG-3′ (sense primer with start at GADD45β −635) and 5′-CCTCCTATTAATAAAAAAACAAAAAC-3′ (anti-sense primer to GADD45β −330). The conditions for the PCR were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 15 minutes; 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 seconds, 60°C for 40 seconds, 72°C for 2 minutes; and 1 cycle at 72°C for 10 minutes. Then PCR products were cloned into a pDrive vector (Qiagen) via the TA ligation. DNA sequencing with the T7 primer at City of Hope DNA Sequencing Facility confirmed the sequences.

Construction and Cloning of GADD45β Expression Plasmid

Total RNA was isolated from logarithmically growing CL-48 cells with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). The cDNA was reverse transcribed from total RNA using AMVRT and Oligo(dT)12-18 primer. The DNA fragment of CL-48 was obtained using RT-PCR with the following primers. The forward and reverse oligonucleotide primer: 5′-GGATCCATGACGCTGGAAGAGCTC-3′ (sense primer with start at GADD45β −6) and 5′-GCGGCCGCTCAGCGTTCCTGAAGAGA-3′ (anti-sense primer to GADD45β +490). The 497-bp PCR product included the GADD45β full-length sequence according to access number AF078077 in GenBank. The thermal cycle profile consisted of denaturing at 94°C for 40 seconds, annealing at 55°C for 40 seconds, and extending at 72°C for 2 minutes in 35 cycles. The PCR product was purified and cleaned up in 1.2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining using the Gel Extract and Purification kit (Qiagen). After agarose gel purification, the coding sequences for GADD45β was inserted into pDrive cloning vector (Qiagen) via U-A ligation according to protocol. Then, the GADD45β fragment was digested by NotI from pDrive-GADD45β (3′ NotI sticky end was obtained from pDrive vector), and cloned into the fluorescence-expressing vector pIRES2-EGFP (B.D. Clonetech). The correct sequence of pIRES2-EGFP-GADD45β plasmid was confirmed by City of Hope National Medical Center Sequence Lab. Escherichia coli bacteria DH5α was cultured along with the appropriate plasmids in LB media containing 100 μg/ml of ampicillin and shaken overnight at 37°C. Maxiprep was performed using the Qiagen plasmid Mega kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Colony Formation Assay and Test TGF-β1 by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

HepG2 cells were transfected with pIRES2-EGFP-GADD45β plasmid or pIRES2-EGFP vector by electroporation in a 4-mm gap cuvette (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) using 45 μs/500 V. Hep3B cells were transfected with pIRES2-EGFP vector, pIRES2-EGFP-GADD45β, pp53-EGFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) or pIRES2-EGFP-GADD45β/pp53-EGFP by electroporation using 80 μs/650 V. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with PBS and collected for flow cytometry and the supernatant was collected using the TGF-β1 Human, Biotrak ELISA system (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) for TGF-β ELISA assay. Above cells were seeded in six-well plates (1000 cells per well) and incubated for 14 days to allow colonies to develop. The medium was then removed and washed with PBS, then fixed and stained with 50% ethanol and 50% methylene blue for 1 hour. The number of stained colonies was scored and counted with Eagle Eye II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The percentage of colony formation was normalized to colonies formed after transfection with empty pIRES2-EGFP vector. All of the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Results

Loss of GADD45β Expression in HCC Cell Lines and Human Tissues

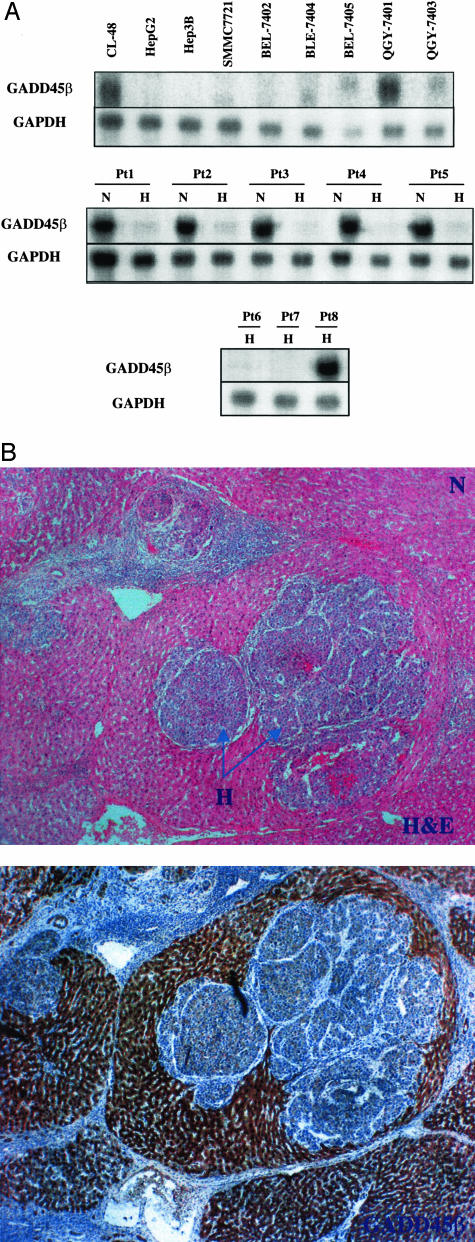

In our previous study, we demonstrated that there is a significant down-regulation of GADD45β in HCC cell lines HepG2 and Hep3B.6 To further validate the down-regulation of GADD45β in HCC cell lines, a panel of HCC cell lines including SMMC-7721, BEL-7402, BEL-7404, EBL-7405, QGY-7701, and QGY-7703 were examined. The GADD45β expression in the panel of cell lines was examined by Northern blot. As expected, there was a decrease in the GADD45β RNA observed in a majority of HCC cell lines; whereas, in the HCC cell line QGY-7701 and normal embryonic liver cell line CL-48 expression of GADD45β was easily detected (Figure 1A, top). To assess the transcriptional level of GADD45β in human tissues, eight fresh HCC samples along with five corresponding nonneoplastic liver samples were investigated in this study. Using hematoxylin and eosin staining, the HCC samples were examined. Patients 6, 7, and 8 demonstrated poorly differentiated and well-differentiated tumors, which were used as controls. The samples from patient 1 to 5 were moderately differentiated with nuclear grade 2 to 3. The Northern blot results showed that GADD45β exhibited very strong expression in five non-HCC liver tissues as opposed to matched HCC tissues (Figure 1A, Pt 1 to Pt 5). The HCC samples from patients 6 and 7 showed decrease expression of GADD45β in Northern blot analysis. As the positive control, the tissue from patient 8 showed very high GADD45β expression. In the IHC study, the staining pattern of GADD45β is the diffusive brownish cytoplasmic tint. The GADD45β immunostaining was predominantly localized in the nonneoplastic hepatic cells. The difference in distribution between GADD45β staining in the HCC area and nonneoplastic liver tissue was noticeable (Figure 1B). Together, these cell lines and tissues constituted a panel of GADD45β-expressing and not expressing cells and tissues for additional analyses to define the mechanism of specific loss of GADD45β expression in HCC.

Figure 1.

Analysis of GADD45β expression in HCC and nonneoplastic liver tissue. A: Northern blot was probed with a 222-bp PCR product that included GADD45β exon 3. The RT-PCR product was generated based on the GADD45β sequence AF078077 in GenBank. GAPDH was used as an internal control for RNA loading. RNAs were isolated from normal liver cell and HCC cells, eight HCC samples, and five matched nonneoplastic liver tissues. N, H, and Pt indicated nonneoplastic liver tissues, HCC tissues, and patient number, respectively. B: IHC study was used to confirm the diagnosis and expression level. Top: H&E-stained sample. The N indicates normal liver tissue and H indicates HCC tissue. Bottom: Stained for GADD45β and shows a diffuse yellowish tint, predominantly in cytoplasm of normal cells. The boundary between cancer tissue and noncancerous tissue was separated by fibrotic tissue. The bottom panel showed very low GADD45β expression in HCC tissue, compared with high GADD45β expression in normal liver tissue. Original magnifications, ×40.

Analyses of the GADD45β Proximal Promoter

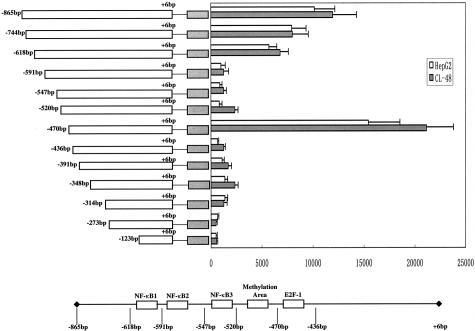

The low expression of GADD45β in HCC suggests that HCC cells may lack a proper response to DNA damage, fail of inhibiting atypical cell growth, and trigger apoptosis.6 One potential mechanism for the specific down-regulation of GADD45β in HCC could be the inability of HCC cells to respond appropriately because of defects in the normal transcription process or the presence of inhibiting factors. To better understand the possible regulatory mechanisms of GADD45β in HCC, we started with the identification of GADD45β proximal promoter region. GADD45β proximal promoter fragments were cloned into a luciferase reporter system, transfected into HepG2 cells, and assessed for their ability to activate luciferase expression. Because HepG2 is a GADD45β-nonexpressing cell, it is not very suitable for the functional localization of the promoter regions. Therefore, we examined the activity of the promoter luciferase reporter in GADD45β-expressing liver cell CL-48. As shown in Figure 2, activation occurred with the GADD45β promoter fragment spanning −865 to −314 in HepG2 and CL-48. Deletion of this fragment from the 5′-end gradually led to decreased promoter activity. In particular, the removal of 27 bp from the −618 fragment caused a significant decrease in promoter activity. Additional truncations led to a slight but insignificant change in promoter activity from −591 to −520. Interestingly, the promoter activity peak appeared with the deletion until −470, which suggested that there exists a putative inhibition region between −520 and −470. In the next analysis of the region from −470 to −314 was examined. We found that the deletion of as few as 34 bp from the 5′-end of this region led to a 24-fold decrease in promoter activity, whereas further truncation from −436 did not influence promoter activity. Also shown in Figure 2, the promoter activity pattern in CL-48 is almost the same as that in HepG2, with the exception of regions −520/−470, −470/−436 and −348/−314. However, only slightly higher promoter activity could be observed in CL-48 in those areas, which suggests other regulatory mechanisms in addition to transcriptional regulation affecting the differential expression between HCC cell and normal liver cell. A search of the TRANSFAC database identified one putative NF-κB binding site (−602 to −593) and one putative E2F-1 binding site (−452 to −444). Both are located in the most significant promoter activity region, −618/−591 and −470/−436. Two other putative NF-κB binding sites between −591 and −520 (−581 to −572 and −537 to −528) were also found with a relatively low score in the database. The NF-κB binding sites have also been identified in a recent report by another group.13 In the putative inhibitor region −520/−470, no marked putative binding sites could be identified. However, the high percentage of CpG islands in this area can be confirmed, which aroused the hypothesis that methylation could be the reason of specific lack of GADD45β expression in HCC. Altogether, these results suggest that several sites in the proximal promoter could be important in the regulation of GADD45β expression. The putative inhibition region may be related to the CpG islands and methylation.

Figure 2.

Identification of GADD45β proximal promoter region. The diagram illustrates the location of putative binding sites for the putative transcription factors. Fragments deleting each binding site were cloned into the pGL3 luciferase reporter plasmid. Relative luciferase activity for each promoter fragment is shown. Putative transcriptional factor binding sites are shown as blank boxes. Experiments were performed in triplicates and the results are presented as the mean ± SD.

Analysis of GADD45β Promoter for CpG Islands

In view of the above promoter analysis, we hypothesized that promoter methylation in putative inhibitor region (−520/−470) may underlie the down-expression of GADD45β in HCC. CpG-rich regions were defined as stretches of DNA with a >50% G+C content, and a >0.6 frequency of observed/expected CpG dinucleotides. Analysis of the GADD45β proximal promoter from −1255 to +6 showed that −1255/1024 and −226/+6 lacked CpG islands. In contrast, the −1025/−225 fragment was a CpG rich region, particularly −625/−425, which had a 65.5% G+C content and a 1.22 frequency of observed/expected CpG. Interestingly, this area covered exactly the putative active promoter region, including three NF-κB consensus binding sites, the E2F-1 consensus binding site and the putative inhibition region. This coincidence further suggested the positive correlation between promoter regulation and hypermethylation. Thus, we focused on the analysis of methylation of this area as a potential mechanism of the down-regulation of GADD45β in HCC.

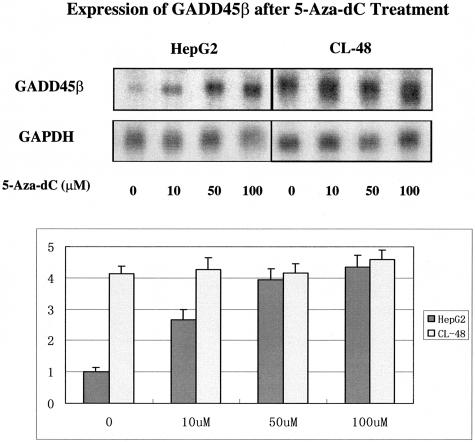

Restore GADD45β Expression in HepG2 after 5-Aza-dC Treatment

To assess the possible specific role of the hypermethylation of GADD45β promoter’s lack of expression in HCC, the demethylation agent 5-Aza-dC14–16 was used to induce GADD45β expression in HepG2 and CL-48 cells. As shown by Northern blot (Figure 3), expression of GADD45β was low in HepG2 cells and could be significantly induced by 5-Aza-dC treatment in a dose-dependent manner. There was an approximate 2.5-fold increase in GADD45β mRNA with 10 μmol/L 5-Aza-dC, a fourfold increase with 50 μmol/L 5-Aza-dC, and a 4.3-fold increase with 100 μmol/L 5-Aza-dC. Also shown in Figure 3, expression of GADD45β was higher in CL-48, but could not be induced by 5-Aza-dC treatment apparently. These results strongly implicated hypermethylation of the promoter in the specific down-regulation of GADD45β in HCC.

Figure 3.

Induction of GADD45β expression after 5-Aza-dC treatment. Forty-eight hours after treatment by different doses of 5-Aza-dC, expression of GADD45β in HepG2 and CL-48 cells was analyzed by Northern blot. The experiments were performed in triplicates and are presented as the mean ± SD. The probe for Northern blot was generated as mentioned in Material and Methods. GAPDH was used as an internal control for RNA loading. ImageQuant version 5.0 was used for quantification.

Hypermethylation Analyses of GADD45β Promoter

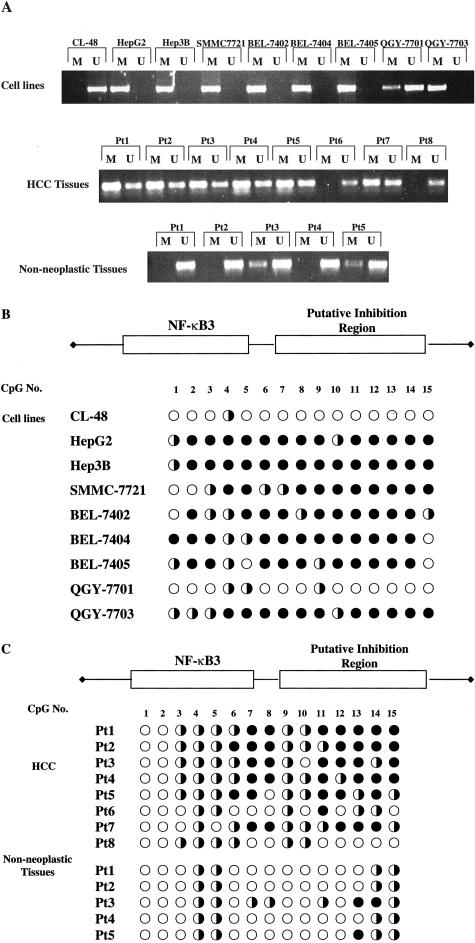

To further assess whether the lack of GADD45β expression in HCC may be the result of promoter hypermethylation, we designed the MSP primers to amplify the PCR products by using methylated or unmethylated DNA as templates. The methylated PCR product could be detected in most of HCC cell lines, whereas no PCR product could be detected in unmethylated specific primers system (Figure 4A). In contrast, the normal liver cell CL-48 that has high level of GADD45β expression showed a lack of apparent methylated PCR products. Meanwhile, the PCR products were amplified both by the methylation-specific and unmethylated primers in GADD45β-expressing HCC cell strain QGY-7701. These results indicated the notable hypermethylation status in most of GADD45β-nonexpressing HCC cell lines and partial methylation in QGY-7701, compared with undetectable methylation in CL-48. In eight HCC samples analyzed, seven HCC samples lacked GADD45β expression (patient 1 to patient 7). Among these seven samples, all could amplify the PCR products with methylation-specific primers except patient 6. Meanwhile, weak PCR products were identified in the unmethylated PCR system, which suggested the existence of some unmethylated DNA in HCC tissues. The only samples having high GADD45β expression was patient 8, and the MSP results showed the specific amplification of unmethylated DNA, rather than methylated DNA. As the control, we analyzed the methylation pattern of five nonneoplastic liver tissues, which corresponded with patient 1 to patient 5 HCC tissues. When unmethylated specific primers were used in the MSP system, the strong PCR products were observed in all five samples. In the methylated PCR system, no methylated DNA was detectable in three samples. Very weak methylated products were found in the other two samples (patient 3 and patient 5), which indicated the existence of the partial hypermethylation in nonneoplastic liver tissues. Taken together, hypermethylated status could be identified in a majority of GADD45β-nonexpressing HCC cell lines and six HCC samples with low levels of GADD45β.

Figure 4.

Analysis of GADD45β promoter methylation in DNA from tissues and HepG2 cells. A: MSP analyses of methylation in DNA from HCC tissues, nonneoplastic liver tissues, and HepG2 cells. Top: The MSP results of nine cell lines. Middle: The MSP results of eight HCC samples. Bottom: Nonneoplastic liver tissues. The M indicates the hypermethylated PCR products and the U indicates unmethylated PCR products. B and C: Nucleotide sequencing of the third NF-κB and the putative inhibition region after sodium bisulfite treatment. •, complete methylation; □, partial methylation, ○, unmethylated.

To further confirm the CpG methylation pattern in GADD45β promoter, we sequenced the sodium bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. The PCR products amplified from sodium bisulfite-treated DNA were cloned into the pDrive plasmid using the TA clone. Positive clones were sequenced to examine the methylated cytosine residues, which would not convert to uracil. The promoter region (−618/−436), containing three NF-κB consensus binding sites, one E2F-1 consensus binding site, and the putative inhibition region, was amplified by PCR using sodium bisulfite genomic DNA as templates. This region spanned 36 CpG dinucleotides sites. Most of the methylation was identified in the 15 CpG dinucleotides located in region −565/−485, which covered the third NF-κB consensus-binding site and the putative inhibition region. The results are summarized in Figure 4, B and C. The sequencing results showed most of the 13 CpG dinucleotides in this area were invariably methylated in GADD45β-nonexpressing HCC cell lines. Partial and very low levels of methylation were also demonstrated in QGY-7701 and CL-48, respectively (Figure 4B). Six HCC samples (patients 1 to 5, and patient 7) with low GADD45β expression showed a high percentage of methylation across this region. However, patient 6 had a low expression of GADD45β and low levels of methylation in HCC tissues, while patient 8 had a high expression of GADD45β with low levels of methylation in HCC tissue. The corresponding nonneoplastic tissues (patients 1 to 5) also showed partial methylation in very low percentages (Figure 4C). No marked methylation was noticed in the first two NF-κB consensus-binding sites and the E2F-1 consensus-binding site. All those results strongly implicated the relationship between hypermethylation in promoter and the low-expression of GADD45β in HCC.

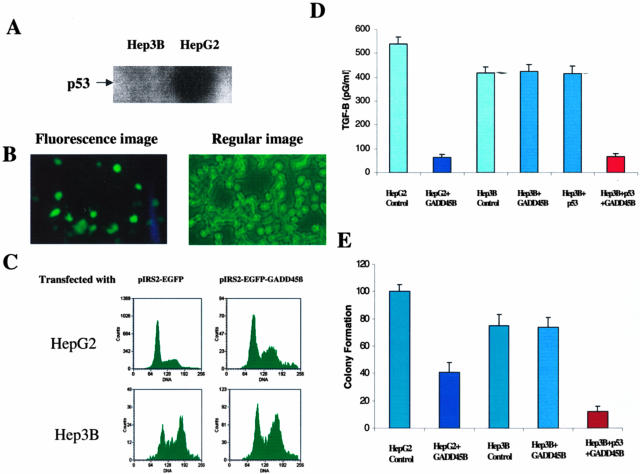

Association of Expression of TGF-β after Introduction of GADD45β Expression Is Dependent on p53 Status

To investigate whether the induction of GADD45β expression is p53 -dependent and associated with TGF-β-related apoptosis, the GADD45β was transfected into HepG2 (p53 WT) and Hep3B (p53 null) cells. The expression level of p53 in each cell is shown in Figure 5A. The fluorescence signal was identified and validates the successful transfectant in Figure 5B. Flow cytometry was further used to evaluate the degree of apoptosis induced by GADD45β in both cell lines (Figure 5C). What is demonstrated in Figure 5C is that the level of apoptosis is significantly elevated in the transfectants of HepG2, but not so in Hep3B cells. Furthermore, the TGF-β expression was examined by ELISA and demonstrated a decrease to 20% in GADD45β transfectant of HepG2 cells to control. There was no difference between the GADD45β transfectant and control of Hep3B in the expression of TGF-β (Figure 5D). When p53 was transfected into Hep3B cells there was no change on TGF-β expression. However, when p53 and GADD45β are co-transfected into Hep3B cells there is a significant decrease in TGF-β expression. The colony formation assay was used in these transfectants (Figure 5E). The GADD45β transfectant of HepG2 cells demonstrated 60% colony formation compared to control. The ability of Hep3B to form colonies was reduced by 25% in comparison to HepG2. The GADD45β transfectant of Hep3B cells demonstrated no significant change in colony formation. Whereas, the p53 and GADD45β co-transfected Hep3B cells demonstrated colony formation that was 10% of Hep3B control. These findings suggested that reduction of TGF-β expression by GADD45β may be dependent on p53 and furthermore restoration of GADD45β may lead to apoptosis via TGF-β-independent pathways.

Figure 5.

Suppression of TGF-β and colony formation by p53-dependent GADD45β expression. A: The p53 expression was examined by Western blot. B: GADD45β expressing fluorescence green staining confirmed the transfection in HepG2 and Hep3B cells (Hep3B cell image not shown). C: The flow cytometry assay examined HepG2 and Hep3B without and with transfection of GADD45β was examined. D: The TGF-β examined by ELISA was described in the Materials and Methods. E: The colony formation assay was described in Materials and Methods. The number of colonies scored in the presence of pIRES2-EGFP vector was designated 100%. All of the experiments were performed at least three times with SD.

Discussion

HCC is one of the most prevalent malignancies worldwide, causing many deaths annually. Recent epidemiological data suggest that the incidence is rising in many western countries.17 The pathogenesis of HCC is complex and multifactorial resulting from environmental exposures such as hepatitis virus, alfatoxin, alcohol, as well as immune-mediated mechanisms. Because the liver is a very important detoxifying organ, hepatocytes are readily exposed to chemical agents, viral infections, and accumulated metabolic products. However, the exact molecular mechanisms of DNA damage from these exposures are primarily unknown and deserve further investigation.

GADD45β (also named MyD118) was first identified as a myeloid differentiation primary response gene activated in murine myeloid leukemia cells (M1) by interleukin-6 on induction of terminal differentiation and associated with growth arrest and apoptosis.18 GADD45β has been associated with control of cellular growth, apoptotic cell death, and cellular response to DNA damage.19–21 Overexpression of GADD45β has been shown to inhibit cell growth in a variety of human tumor cell lines and in NIH3T3 fibroblasts, resulting in suppression of colony formation.18 GADD45β was also found to be a primary response gene to TGF-β, a growth inhibitory and proapoptotic cytokine. Our current results indicate that the TGF-β expression was decreased to 20% in the GADD45β transfectant HepG2 cell. Blocking GADD45β expression in M1 cells by anti-sense RNA was found to compromise TGF-β-mediated apoptosis. Ectopic expression of bc1–2 in M1 cells, which blocked TGF-β-induced apoptosis, resulted in reduced levels of GADD45β transcription. In contrast, deregulated expression of either c-myc or c-myb in M1 cells, which accelerated TGF-β-induced apoptosis, markedly elevated the level of GADD45β transcription. These findings are consistent with GADD45β being proapoptotic modulator.18,19,22 However, the role of epigenetic silencing of GADD45β in liver tumorigenesis needs further investigation.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that GADD45β was down-regulated in HCC consistently and significantly when compared to matched nonneoplastic liver tissue using the microarray assay, the IHC, and the quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Furthermore, we observed that down-regulation of GADD45β was strongly correlated with less differentiated tumors and a higher nuclear grade of HCC. The IHC study of multiple human cancer tissues revealed that GADD45β was highly expressed in other human cancer tissues and the decreased expression was specific to HCC.6 Our results suggested that the specific lack of GADD45β expression plays an important role in HCC carcinogenesis. Understanding the molecular basis of GADD45β down-regulation and possible ways to induce GADD45β expression in chronic liver disease or HCC could potentially be a powerful therapeutic approach.

Several strategies were designed to understand the mechanism of GADD45β regulation in HCC. It is generally accepted that changes in transcriptional regulatory pathways may be essential to the process of malignant transformation of cells. Therefore, in this study, we focused on elucidating the GADD45β transcriptional regulation to understand the mechanism of HCC-specific loss of GADD45β expression. GADD45β-expressing normal liver cell CL-48 and GADD45β-nonexpressing HCC cell HepG2 were used as a pair of cells in promoter-linked reporter system. Several putative binding sites were identified by deletion analysis, according to the consensus sequences of NF-κB and E2F-1 in the TRANSFAC database.19,23,24 Moreover, a putative inhibition region was also identified in proximity to the third NF-κB binding sites. Furthermore, the promoter activity pattern was very similar in CL-48 and HepG2 and only slightly higher in CL-48. These results suggested that there are additional mechanisms involved besides alteration of transcription factor binding activity resulting in the decrease in expression of GADD45β. The high percentage of CpG islands in the promoter region led us to hypothesize the possible role of methylation in altering the expression of GADD45β in HCC. Based on the recent reports, the hypermethylation of the promoter region or other regions rich in CpG represent an important mechanism to inactivate specific gene expression during carcinogenesis.25 We considered the possibility that down-regulation of GADD45β might be caused by hypermethylation of the promoter region.

DNA methylation is an enzyme-related chemical modification to the DNA structure. The methyl group is covalently bonded to the 5-carbon on the cytosine base.26 Methylation only occurs on the CpG dinucleotides, because the methylation only happens on the cytosine bases, which directly connect to a guanine by the phosphodiesterase link. It has been reported that several mechanisms are involved in the repression of gene expression. The physical impact after methylation could influence the binding of transcriptional factors. Some specific proteins, such as MeCP2, could bind to methylated CpG dinucleotides through the methyl-CpG binding domain. Then, the transcriptional repression domain will form the complex with a variety of co-repressor factors, followed by the changes in chromatin structure and histone acetylation. Active transcription will be blocked because of inaccessibility to consensus or DNA binding region. Therefore, we hypothesize that the demethylation agent could restore the gene expression when methylation happens at the promoter region.

Analysis of the GADD45β promoter revealed that the CpG content and the CpG dinucleotide frequency were more than expected in region −1025/−225, and had a particular high density in region −625/−425. Interestingly, the −625/−425 region covered the putative inhibition region exactly. This observation may suggest a positive correlation between promoter regulation and hypermethylation. To explore the functional evidence, 5-Aza-dC was first used to assess whether the demethylating agents could restore GADD45β expression in HepG2. The dose-dependent increases in the Northern blot strongly implicated the role of hypermethylation of the promoter in GADD45β regulation.

On the basis of the possible hypermethylation status of the promoter, we designed the MSP and sequencing primers to detect the existence of methylation within the −565/−485 fragment, which covered the third NF-κB consensus binding site and the putative inhibition region. The methylation-based PCR has a high sensitivity of methylation detection, further confirmed by sequencing examination. Our results confirmed the hypermethylation status in HepG2 and other GADD45β-nonexpressing HCC cell lines. To validate that the observations in cell lines are reflected in clinical cases, we examined the promoter methylation status in eight fresh microdissected HCC samples and five corresponding nonneoplastic liver samples. The results showed that six of seven HCC samples with low expression of GADD45β showed a high level of promoter methylation in this area. In contrast, very low levels of methylation could be detected in one GADD45β-expressing non-HCC cells and five nonneoplastic liver tissues. When the unmethylated primers were used in MSP systems, the PCR products could be amplified from all of the tissue samples, while most of HCC cell lines did not show any unmethylated PCR product. The difference in PCR product could be because of the in vivo background of unmethylated DNA: the partial methylation status within the corresponding promoter region in HCC tissues, compared to the complete methylation status of in vitro cultured HCC cells. On the other hand, the PCR products could be amplified in two nonneoplastic liver tissues using methylation-specific primers. This result could contribute to the methylation background in normal mammalian tissues or to the partial methylation in liver tissues after long-term influence by in vivo or in vitro toxic agents. Taken together, the MSP analyses corroborated our hypotheses of the presence of methylation in the putative inhibition region.

GADD45β protein has a known role in DNA damage, cell-cycle checkpoint, and apoptosis.27 The p53 mutation has been reported to correlate with GADD45β down-regulation.28 In our current study, the hypermethylation of GADD45β was found in HCC tissue and not in adjacent normal tissue and cell lines. The GADD45β methylation was correlated with mRNA expression. This correlation is further related to the presence of mutated p53. Toyota and colleagues,29 reported that p16 methylation is inversely correlated with p53 mutation in colon cancer. Recent reports by Youssef and colleagues,30 revealed an inverse correlation was found between the methylation of RAR-β gene and p53 mutation. The head and neck cells with wild-type p53 gene had a hypermethylated RAR-β2 gene. Whereas, the GADD45β is a downstream effector of p53 that requires further exploration. Overall, p53 may play role in the regulation of the GADD45β gene in various mechanisms such as methylation or transcription binding. Thus, the properties of GADD45β gene regulation in liver cell transformation could be mediated by the cellular effects of the p53 require further elucidation.

It has been reported that GADD45β-mediated p38 MAP kinase by TGF-β was Smad-dependent.8 Using the anti-sense inhibitor of GADD45β expression led to suppression of the TGF-β-induced p38 activation. The overexpression of GADD45β may activate the p38 MAPK via the MTK1 pathway. The mechanisms of TGF-β-induced apoptosis are particularly important in hepatocytes.8 In this current study, we further suggest that TGF-β, GADD45β, and Smad paradigm may be directed by p53 status. The reduction of TGF-β by GADD45β expression indicates the feedback regulation. Moreover, our data suggested that TGF-β expression was not directly correlated with apoptosis in GADD45 β transfectant HepG2 or Hep3B. Thus, TGF-β-mediated apoptosis may be dependent on p53 status and GADD45 β regulation as well. However, our finding could not exclude the evidence that there are separate and independent pathways that may be complementary to TGF-β-mediated apoptosis.

Presently, the molecular mechanism of the specific loss of GADD45β expression in HCC remains unknown. The promoter studies from our laboratory and other groups have identified several transcriptional factors binding sites, such as NF-κB and E2F-1. Some agents including cytokines, SAMe, and Oxaliplatin, could induce GADD45β expression by increasing the promoter binding capacity. Studies reported here suggest that promoter hypermethylation, especially in the putative inhibition region, might play an important role in GADD45β transcriptional repression. In future studies, we will examine the methylation status in a large number of clinical samples. The liver tissues from chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and different HCC stages will be studied to elucidate the role of DNA methylation in hepatocarcinogenesis. The possibility of methylation exams as the diagnosis marker will be further focused on. Understanding the molecular basis of GADD45β down-regulation and possible ways to induce GADD45β expression in chronic liver disease or HCC could potentially give rise to future therapeutic approach.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Yun Yen, M.D., Ph.D., F.A.C.P, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1500 E. Duarte Rd., Duarte, CA 91010-3000. E-mail: yyen@coh.org.

Supported by the Parsons Foundation and the Sino-American Cancer Foundation.

References

- Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5–26. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M, Saito H. A family of stress-inducible GADD45-like proteins mediate activation of the stress-responsive MTK1/MEKK4 MAPKKK. Cell. 1998;95:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Hara T, Hibi M, Hirano T, Miyajima A. A novel oncostatin M-inducible gene OIG37 forms a gene family with MyD118 and GADD45 and negatively regulates cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24766–24772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Bae I, Krishnaraju K, Azam N, Fan W, Smith K, Hoffman B, Leibermann DA. CR6: a third member in the MyD118 and GADD45 gene family which functions in negative growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:4899–4907. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, David D, Zhou B, Chu PG, Zhang B, Wu M, Xiao J, Han T, Zhu Z, Wang T, Liu X, Lopez R, Frankel P, Jong A, Yen Y. Down-regulation of growth arrest DNA damage-inducible gene 45 β expression is associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;6:1961–1974. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J, Ghiassi M, Jirmanova L, Balliet AG, Hoffman B, Fornace AJ, Jr, Liebermann DA, Böttinger EP, Roberts AB. Transforming growth factor-β-induced apoptosis is mediated by Smad-dependent expression GADD45β through p53 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43001–43007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa M, Tatebayashi K, Itoh F, Adachi M, Imai K, Saito H. Smad-dependent GADD45β expression mediates delayed activation of p53 MAP kinase by TGF-β. EMBO J. 2002;21:6473–6482. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng CX, Zeng ZC, Wang JY. Docetaxel inhibits SMMC-7721 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells growth and induces apoptosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:696–700. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i4.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HY, Yang YL, Gao YY, Wu QL, Gao GQ. Effect of arsenic trioxide on human hepatoma cell line BEL-7402 cultured in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:681–687. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v6.i5.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XW, Xie H. Presence of Fas and Bcl-2 proteins in BEL-7404 human hepatoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:540–543. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.i6.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9821–9826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, Nguyen DU, Papa S, Jones J, Cox C, Gelinas C, Franzoso G. Regulation of the gadd45beta promoter by NF-kappaB. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:491–503. doi: 10.1089/104454902320219059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AT, Evron E, Umbricht CB, Pandita TK, Chan TA, Hermeking H, Marks JR, Lambers AR, Futreal PA, Stampfer MR, Sukumar S. High frequency of hypermethylation at the 14-3-3 sigma locus leads to gene silencing in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6049–6054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100566997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widschwendter M, Berger J, Hermann M, Muller HM, Amberger A, Zeschnigk M, Widschwendter A, Abendstein B, Zeimet AG, Daxenbichler G, Marth C. Methylation and silencing of the retinoic acid receptor-β2 gene in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:826–832. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.10.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini V, Kantarjian HM, Issa JP. Changes in DNA methylation in neoplasia: pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:573–586. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi A, Lord KA, Hoffman-Liebemann B, Liebermann DA. Sequence and expression of a cDNA encoding MyD118: a novel myeloid differentiation primary response gene induced by multiple cytokines. Oncogene. 1991;6:165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer T, Chen X, Karas H, Kel AE, Kel OV, Liebich I, Meinhardt T, Reuter I, Schacherer F, Wingender E. Expanding the TRANSFAC database towards an expert system of regulatory molecular mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:318–322. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Lord KA, Alamo I, Jr, Hollander MC, Carrier F, Ron D, Kohn KW, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA, Fornace AJ., Jr The GADD and MyD genes define a novel set of mammalian genes encoding acidic proteins that synergistically suppress cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2361–2371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornace AJ, Jr, Jackman J, Hollander MC, Hoffman-Liebermann B, Leibermann DA. Genotoxic-stress-response genes and growth-arrest genes. GADD, MyD, and other genes induced by treatments eliciting growth arrest. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;663:139–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb38657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvakumaran M, Lin HK, Sjin RT, Reed JC, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. The novel primary response gene MyD118 and the proto-oncogenes myb, myc, and bcl-2 modulate transforming growth factor β1-inductd apoptosis of myeloid leukemia cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2352–2360. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenardo MJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: a pleiotropic mediator of inducible and tissue-specific gene control. Cell. 1989;58:227–229. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevins JR. E2F: a link between the Rb tumor suppressor protein and viral oncoproteins. Science. 1992;258:424–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1411535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin SB, Esteller M, Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Schuebel K, Herman JG. Aberrant patterns of DNA methylation, chromatin formation and gene expression in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:687–692. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajed SA, Laird PW, DeMeester TR. DNA methylation: an alternative pathway to cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:10–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. MyD in negative growth control. Oncogene. 1998;17:3319–3329. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Q, Lord KA, Alamo I, Jr, Hollander MC, Carrier F, Ron D, Kohn KW, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA, Fornace AJ., Jr The gadd and MyD genes define a novel set of mammalian genes encoding acidic proteins that synergistically suppress cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2361–2371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota M, Ohe-Toyota M, Ahuja N, Issa JP. Distinct genetic profiles in colorectal tumors with or without the CpG island methylator phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:710–715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef EM, Lotan D, Issa JP, Wakasa K, Fan YH, Mao L, Hassan K, Feng L, Lee JJ, Lippman SM, Hong WK, Lotan R. Hypermethylation of the retinoic acid receptor-β2 gene in head and neck carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1733–1742. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]