Abstract

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of lymphocytes, especially CD4+ T cells, in early lesions of atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. However, the role of other T cell subpopulations, like CD8+ T cells or TCRγδ T lymphocytes, is not yet clear. We have therefore generated apolipoprotein E-deficient mice genetically deficient in specific T lymphocyte subpopulations and measured atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus and en face whole aorta preparation at 18 weeks and at 1 year of age. Whereas TCRγδ+ T lymphocytes appeared to play a modest role, TCRαβ+ T lymphocytes played a major role as their deficiency significantly prevented early and late atherosclerosis at all arterial sites. However, neither CD4+ nor CD8+ T cells induced any significant decrease of the lesions at the aortic sinus, suggesting that compensatory proatherogenic mechanisms are operating at this site. Interestingly, the absence of CD4+ T cells led to a dramatic increase in early lesion abundance at the level of the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta, which was still obvious at 1 year. In conclusion, whereas the TCRαβ+ lymphocyte subset in its whole contribute to aggravate both early and late atherosclerosis, the CD4+ T subpopulation appears to be critically protective at the level of the lower part of the aorta.

Recent cumulative evidence has suggested that both innate and adaptive immune responses modulate the rate of lesion progression (reviews in1–4). Recent studies have confirmed the presence of T lymphocytes in early lesions of atherosclerosis at the level of the aortic sinus5–7 as well as their functional importance,8 especially for the CD4+ T cells.9 However, the roles of other T lymphocyte subpopulations, like CD8+ T cells, as well as TCRγδ+ T lymphocytes, also detected in murine or human lesions,7,10,11 have not yet been defined.

We decided to study the effects of T lymphocyte subpopulations on the development of atherosclerotic lesions in female apolipoprotein-E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice by a compound knockout breeding strategy. Our data show that TCRγδ+ T lymphocytes play a minimal role and that TCRαβ+ T lymphocytes exert a proatherogenic activity. The atherogenic role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells appears of a similar magnitude as their respective deficiency led to lesion size comparable to immunocompetent but higher than TCRαβ+ T lymphocyte-deficient mice. Unexpectedly and in contrast to what was observed at the level of the aortic sinus, CD4+ T cell-deficient mice demonstrated a clear-cut increase in lesion abundance at the level of the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta. This strongly suggests a protective role for regulatory CD4+ T lymphocytes with an arterial site-specific effect.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The specific pathogen-free conditions of animal care and regular chow diet feeding have been described previously.12,13 To generate the new double-deficient models, ApoE−/− female mice were obtained from Transgenic Alliance (IFFA CREDO, l’Arbresle, France). CD4-deficient14 (CD4−/−) and CD8-deficient15 (CD8−/−) male mice were obtained from CDTA (Orleans, France). TCRβ-deficient16 (B6.129P2-Tcrbtm1Mom, TCRβ−/−), and TCRδ-deficient17 (B6.129P2-Tcrdtm1Mom, TCRδ−/−) male mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice had been backcrossed into a C57Bl/6 background for more than 10 generations. They were crossed once more with female ApoE−/− mice. Heterozygous ApoE−/−/TCRβ+/−, ApoE−/−/CD4+/−, ApoE−/−/CD8+/−, and ApoE−/−/TCRδ+/− populations were generated and used as the parental genotypes. Confirmation of gene disruption was screened by PCR genotyping, following protocols recommended by CDTA or the Jackson Laboratories, and phenotyping of blood lymphocytes or splenocytes by flow cytometry. Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-αβTCR (clone H57–597), anti-γδTCR (clone GL3), anti-CD4 (clone RM4–5), anti-CD8 (clone 53–6.7), anti-CD19 (clone 1D3), and corresponding isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Staining of splenocytes was performed after blocking Fc receptor with anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2) and incubation for 30 minutes with appropriate dilutions of various fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs. Flow cytometry was performed on a four-color FACScalibur (BD Biosciences). The lymphocyte and macrophage gates were defined on the basis of forward and side scatter, and results analyzed using CellQuestPro software.

Because the initial focus of our studies concerned the protective effect induced by estrogen hormones, only the female offspring of these heterozygous strains were studied. Mice were sacrificed at the age of 18 weeks or at 1 year with an overdose of ketalar after a 16-hour fast. Blood was collected for serum lipid analysis by orbital punction.12 All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the European Institute for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Tissue Preparation and Lesion Analysis

The circulatory system was perfused with 0.9% NaCl by cardiac intraventricular canalization. The heart and origin of the ascending aorta were removed and snap-frozen. Surface lesion area at the aortic root was measured by computer-assisted image quantification after Oil red coloration as previously described12 except that a Leica image analyzer was used instead of a Biocom in our previous studies. Collagen fibers were stained with Sirius red. The rest of the entire aortic tree was removed and cleaned of adventitia, split longitudinally to the iliac bifurcation, and pinned flat on a dissection pan for analysis by en face preparation. Images were captured using a Sony-3CCD video camera and the fraction covered by lesions evaluated as a percentage of the total aortic area.

Immunohistochemistry

Cryostat sections from the proximal aorta were fixed in acetone, air-dried, and reacted with a primary rat monoclonal anti-mouse macrophage (clone MOMA-2 from Serotec) used at a 1:50 dilution, a primary goat polyclonal anti-CD3 (clone M-20 from Santa Cruz) used at a 1:100 dilution, or a rat monoclonal anti-mouse H-2 1-A (I-Ab) (Biosource International) used at a 1:10 dilution. Then, sections were incubated with the corresponding preadsorbed secondary biotinylated antibodies (Vector Laboratories): binding of rat monoclonal anti-macrophage was revealed using biotinylated rabbit anti-rat IgG and binding of goat polyclonal anti-CD3 was revealed using biotinylated horse anti-goat IgG. The binding of the biotinylated antibodies was visualized with an avidin DH-biotinylated peroxidase complex (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) and AEC peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). Countercoloration was carried out using Mayer’s hemalum. Macrophage, T cell, and I-Ab quantification was determined by scoring samples from at least four sections per animal. Two investigators who were blinded to the sample identity performed analysis.

Analysis of Serum Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Immunoglobulins

Serum cholesterol concentration was determined by an enzymatic assay adapted to microtiter plates using commercially available reagents (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Germany). Lipoprotein cholesterol profiles were obtained by fast protein liquid chromatography.18 Two hundred μl of serum was injected on a Sepharose 6 HR 10/30 prepacked column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and lipoproteins were separated at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min of 10 mmol/L phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.01% ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 0.01% NaN3. The effluent was monitored at 280 nm and collected in 0.27-ml fractions. Cholesterol concentration was measured in each fraction. Serum titers of total, IgG, and IgM immunoglobulins were measured by ELISA and expressed as arbitrary units representing absorbance to plates coated with anti-mouse Ig capture antibodies. In specific conditions, the titers of anti-MDA-LDL, were also measured by ELISA and expressed as arbitrary units representing absorbency to plates coated with malondialdehyde-modified low density lipoprotein (MDA-LDL) prepared as previously described.19

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as means ± SEM. The effects of the genotype were studied for each parameter (body weight, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, lesion area), by one-factor analysis of variance (Bonferroni/Dunn’s test) comparing each group of specifically immunodeficient mice with its corresponding immunocompetent group; P < 0.05 was considered as significant. Calculations were made using Statview statistical software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA).

Results

Effect of Genotype Change on Mouse Phenotype

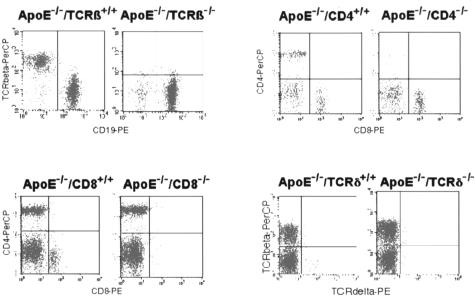

Mice specifically deficient in ApoE and either TCRαβ+, CD4+, CD8+, or TCRγδ+ lymphocytes were overtly normal, developed normally, appeared healthy, and were fertile with an average litter size of five pups at the expected Mendelian ratio. Gene disruption was confirmed by PCR genotyping and lymphocyte phenotyping of blood lymphocytes or splenocytes by flow cytometry (Figure 1). The flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes showed the expected changes in percentage of the lymphocyte populations induced by the different manipulations. However, a greater number of CD8+ T cells was observed in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice (19 × 106/spleen versus 10 × 106/spleen, P < 0.001) and of double-negative CD4−CD8− T cells (5 × 106/spleen versus 2 and 1 × 106/spleen, respectively, P < 0.001) when compared with ApoE−/− or ApoE−/−/CD8−/− mice. None of the manipulations influenced the monocyte/macrophage/dendritic cell population (8 ± 2% of total splenocytes).

Figure 1.

Characterization of ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, ApoE−/−/CD4−/−, ApoE−/−/CD8−/−, and ApoE−/−/TCRδ−/− mice by flow cytometric analysis. Splenocytes were co-labeled with anti-TCRβ-PerCP/anti-CD19-PE, anti-CD4-PerCP/anti-CD8-PE, and anti-TCRβ-PerCP/anti-TCRδ-PE conjugated antibodies.

Serum levels of IgG and IgM immunoglobulins were similar in the different groups except in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice, which displayed lower levels of both IgG and IgM classes (P < 0.01) when compared with ApoE−/−, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Body Weight (B. W., g), Total Serum Cholesterol (T. C., g/l), and Immunoglobulin Titers (Arbitrary Units/ml) of Immunocompetent ApoE−/− Control and Immunodeficient ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, CD4−/−, CD8−/− or TCRδ−/− Female Mice, at 18 Weeks and at 1 Year of Age

| Genotype | 18 weeks

|

1 year

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. W. | T. C. | IgM | IgG | B. W. | T. C. | |

| ApoE−/− | 22.0 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 25.5 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| ApoE−/−TCRβ−/− | 21.0 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 25.1 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| ApoE−/−CD4−/− | 19.5 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1* | 0.6 ± 0.1* | 23.0 ± 1.8 | 4.0 ± 0.6 |

| ApoE−/−CD8−/− | 21.5 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 28.4 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| ApoE−/−TCRδ−/− | 20.1 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

Results are means ± SEM (n ≥ 9 at 18 weeks, n = 5 at 1 year). ND, not done.

Statistically different from the corresponding immunocompetent mice.

Some of the TCRβ-deficient mice developed inflammatory bowel disease with rectal prolepsis, sometimes with diarrhea, and were excluded from the studies.

At 18 weeks of age, body weight and serum lipids, measured in ApoE−/−/TCRβ+/+,/CD4+/+,/CD8+/+,/TCRδ+/+, ApoE−/−/TCRβ+/−,/CD4+/−,/CD8+/− and/TCRδ+/−, were not significantly different which is consistent with the absence of gene dosage effect on these parameters. These parameters were not significantly different in the different groups of immunodeficient mice either (Table 1). Similarly, serum lipid analysis by fast performance liquid chromatography showed no difference between the different groups in the rapidly eluting very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) peak (50.3 to 59.1%), the middle intermediary density lipoprotein/low density lipoprotein (IDL/LDL) peak (33.9 to 40.3%), and the slowly eluting, much smaller high density lipoprotein (HDL) peak (7 to 10.9% of total lipidogram).

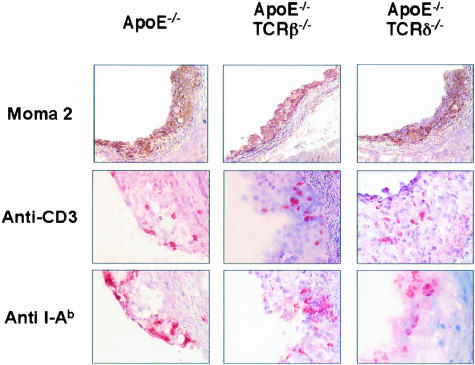

Effect of Genotype on Lesion Area in the Aortic Sinus

Again, no significant difference was noted between the corresponding homozygous (+/+) or heterozygous (+/−) immunocompetent mice concerning fatty streak area at the aortic root. At 18 weeks of age, lesion area was lower in ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/− mice when compared with their corresponding immunocompetent controls (Table 2). Lesions were not significantly different in the other groups, including the ApoE−/−/TCRδ−/− mice that were not studied further. The magnitude of lesion area was more scattered for ApoE−/−/CD4−/−. Quantitative histological analysis did not reveal a difference in the macrophage content (71 ± 3%), CD3+ lymphocytes (2 ± 1%) as well as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-positive cells (12 ± 2%) in the different groups of mice. Remarkably, macrophage, lymphocyte, as well as MHC class II-positive cell infiltration was comparable in ApoE−/− control as well as in ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/− and ApoE−/−/TCRδ−/− mice (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Aortic Root Lesion Area (μm2) in 18 week- and 1-Year-Old Immunocompetent ApoE−/− Control and Immunodeficient ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, CD4−/−, CD8−/−, or TCRδ−/− Female Mice

| Genotype | 18 weeks | 1 year |

|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− | 73214 ± 2963 | 958533 ± 57120 |

| ApoE−/−TCRβ−/− | 37048 ± 4749* | 594500 ± 39881* |

| ApoE−/−CD4−/− | 77745 ± 12629 | 793128 ± 39376 |

| ApoE−/−CD8−/− | 76909 ± 4722 | 869938 ± 35516 |

| ApoE−/−TCRδ−/− | 57589 ± 3737 | ND |

Results are means ± SEM.

, Statistically different from the corresponding immunocompetent mice (n ≥ 9 at 18 weeks and n = 5 at 1 year of age).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis of lesions from ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, and ApoE−/−/TCRδ−/− mice labeled with anti-mouse macrophage, MOMA-2, anti-CD3, or anti-H-21-A (I-Ab) antibodies at 18 weeks of age. Areas of high labeling have been chosen to demonstrate the presence of the different cell populations.

At 1 year of age, lesions of the aortic sinus were advanced in all groups of mice (Table 2). They were still significantly lower in ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/− mice. Again, quantitative histological analysis did not demonstrate a difference in the composition of the plaques, either in terms of subendothelial macrophage infiltration (30 ± 4%) and collagen content (50 ± 8%). In all groups, lymphocytes were only rarely detected (< 0.5%).

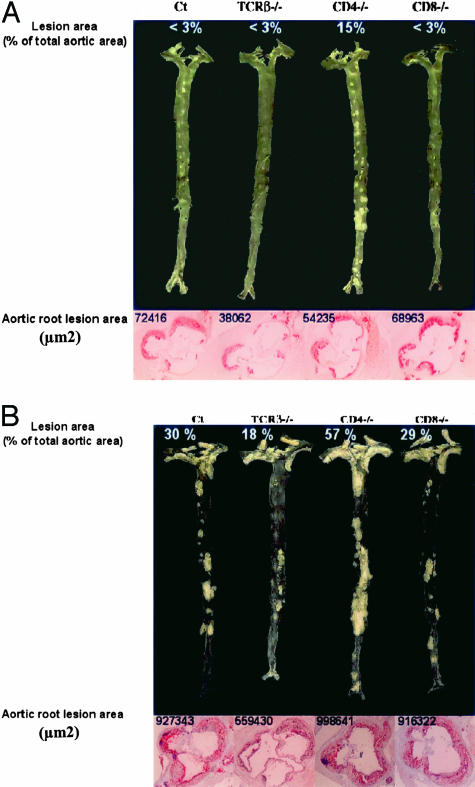

Effect of Genotype on Lesion Area in the Aorta

In agreement with a previous description,20 en face preparations of the aortic tree revealed that, at 18 weeks of age, lesion distribution was identifiable at predilection sites including the aortic arch and the orifices of the brachiocephalic, left subclavian, common carotid, and intercostal arteries (Figure 3A). Although lesion surface area tended to be lower in ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, a quantitative assessment was difficult because of the low level of lesions (< 3.0% of the total aortic area) except the ApoE−/−/CD4−/− group of mice (Table 3). In this last group, lesions were dramatically increased as early as 18 weeks at the orifice of the large abdominal arteries (averaging 20% of total abdominal area), especially the celiac trunk and renal arteries (Figure 3A). This level was significantly higher than that of the descending thoracic aorta (9%) and of the aortic arch (8%). Interestingly, anti-MDA-LDL titers, the prototypic antibody in atherosclerosis, were significantly lower in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− compared with ApoE−/− mice for both the IgG (0.15 ± 0.04 versus 0.07 ± 0.01 arbitary units (AU), P < 0.05) and IgM (0.13 ± 0.02 versus 0.04 ± 0.01 AU, P < 0.02) classes, respectively.

Figure 3.

En face aorta preparations and sections through the aortic root in the vicinity of the aortic valves from respective genotypes observed in mice fed a normal chow for 18 weeks (A) or 1 year (B). Corresponding measurement of lesion areas are given to compare to the data in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 3.

Lesion Area as % of Total Aortic Area in 18 Week- and 1-Year-Old Immunocompetent ApoE−/− Control and Immunodeficient ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/−, CD4−/−, CD8−/−, or TCRδ−/− Female Mice

| Genotype | 18 weeks | 1 year |

|---|---|---|

| ApoE−/− | < 3.0 | 34.5 ± 2.0 |

| ApoE−/−TCRβ−/− | < 3.0 | 22.1 ± 1.1* |

| ApoE−/−CD4−/− | 14.2 ± 1.5 | 56.0 ± 3.3* |

| ApoE−/−CD8−/− | < 3.0 | 34.0 ± 2.3 |

| ApoE−/−TCRδ−/− | < 3.0 | ND |

Results are means ± SEM. ND, not done.

, Statistically different from the corresponding immunocompetent mice (n = 5 at 18 weeks and ≥ 6 at 1 year of age).

At 1 year of age, lesions were still smaller in ApoE−/−/TCRβ−/− than in ApoE−/− mice. In contrast, and in agreement with the early lesions observed at 18 weeks of age, ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice presented more lesions than all of the other groups, extending throughout the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta (Table 3, Figure 3B).

Discussion

Although T lymphocytes have been detected in atherosclerotic lesions and are thought to play a predominant role in early atherogenesis, the role of the different subsets remains largely unknown. Although commonly viewed as functionally independent, TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ cells have clear relatedness as recently reported.21 Nevertheless, we can observe that TCRγδ+ cells played a modest role and that mainly TCRαβ+ T lymphocytes exhibited a deleterious role at both 18 weeks and 1 year of age in female mice fed a chow diet. This emphasizes the role of the immune system not only in early fatty streak, but also in late atherosclerosis, whereas previous work using a model of LDL-receptor/RAG1 double-deficient mice tended to restrict the importance of lymphocytes to early atherosclerosis.6 Considering the lesion topography, the TCRαβ+ cells not only played a crucial role in the aortic sinus, but also in the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta. The difference was less apparent at the level of the aortic arch, suggesting a lesser role of T lymphocytes at this anatomical site. This last result is in line with previous reports suggesting that lymphocytes play no role in the development of atherosclerosis in the brachiocephalic artery.8,22 At these sites, inflammatory products released by platelets,23,24 such as CD40L or thrombin-induced reactive oxygen species,25 could substitute for those generated by immune reactions.

As the development of the disease was very similar in ApoE−/−/CD8−/− and ApoE−/− mice both at 18 weeks and at 1 year of age and at all examined arterial sites, our data do not suggest an important role of CD8+ T lymphocytes subpopulation in presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Indeed, the CD4+ T lymphocytes have been suggested to play the most important role in atherosclerosis, in particular because they were found to be the most abundant subpopulation in early lesions.9 The present data obtained in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice confirm their key but complex role. On one hand, lesion area in the aortic sinus of ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice was comparable to that of ApoE−/− mice at 18 weeks and at 1 year of age. On the other hand, en face analysis at both 18 weeks and 1 year of age, consistently showed widespread lesions, especially in the descending thoracic and the abdominal aorta. Such a site-specific aggravation of the atherosclerotic process could be due to several non-exclusive mechanisms. First, in absence of CD4+ T lymphocytes, other immune cells, in particular CD8+ lymphocytes, could reveal a deleterious effect. As shown here and previously reported,26 ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice presented with a greater number of CD8+ and double-negative CD4−CD8− cells than ApoE−/− mice. Moreover, in this situation, the CD8+ population has been shown to contain a large fraction of MHC class II-restricted cells in addition to the conventional class I-restricted cells.27 The increased lesions seen in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice might then reflect such perturbations in CD8 lineage commitment. Interestingly, it has been recently shown that expression of a “foreign” antigen on vascular smooth muscle cells can lead to cytotoxic attack by CD8+ T cells and results in significant aggravation of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice.28 Second, the possibility that CD4+ regulatory T cells serve to keep in check such antigen-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes should also be considered. Indeed, regulatory T cells have recently been shown to reduce the development of experimental atherosclerosis.29 The role of the natural killer T (NKT) lymphocytes, able to interact with the non-polymorphic non-classical MHC molecule CD1 presenting lipid and glycolipid antigens,30,31 is not favored by the recent observation of the aggravating role of this lymphocyte subset.32 On the contrary, a role for the naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ or induced CD4+, Th3 and type 1T regulatory lymphocytes29,33 is more plausible. Adoptive transfer of these T cell subsets in ApoE−/−/CD4−/− mice should confirm this possibility and precise the mechanisms involved. Third, B cells have previously been shown to protect against atherosclerosis,34,35 and it is plausible that humoral immunity protection could be altered by deficit in CD4+ T cells. This concept is supported by the observed decrease in both total and anti-MDA-LDL-specific serum immunoglobulin titers.

Finally, it is interesting to compare the location of the atherosclerotic lesions elicited by CD4+ T cell deficiency and by angiotensin II infusion. Indeed, the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta has been reported to be an exquisite site of atherosclerotic lesions in angiotensin II-induced hypertension,36 leading to aortic aneurysms.37,38 Although no trend to aortic dilation was observed in this work, the peculiar lesion topography associated with the specific CD4+ T lymphocyte deletion should be taken into consideration in future studies.

In conclusion, the present work directly demonstrates an involvement of the different populations of lymphocytes in the development of the atherosclerotic process. This involvement varies with both time and the topography of the lesions. Determination in the aortic sinus at 18 weeks of age correctly reflects the integrated participation of the different lymphocyte populations in immunocompetent mice, as previously suggested.39 However, the descending thoracoabdominal aorta appears exquisitively sensitive to the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes both at early and late stages of the disease. This observation again emphasizes the necessity to study the whole arterial tree to precisely depict the respective roles of the cellular actors involved in the atherosclerotic scenarios. The present models will be useful to further explore the implication of the specific role of lymphocyte subpopulations under various protective or aggravating conditions as well as after specific complementation. They should significantly help to approach the human atherosclerotic process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. P. Guillou, C. Castano, A. Schambourg, and M. Larribe for technical and secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Francis Bayard, INSERM U589, Institut L. Bugnard, 1 avenue Jean Poulhès, 31403 Toulouse Cédex, France. E-mail: bayard@toulouse.inserm.fr.

Supported in part by INSERM, the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie (Université Paul Sabatier), Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Theramex Laboratories, Fondation de France, European Vascular Genomics Network No. 503254, and the Conseil Régional Midi-Pyrénées. R. Elhage has been supported by a grant from the French Society of Atherosclerosis.

J.J.’s present address is Department of Pharmacology, Jagiellonian University School of Medicine, Grzegorzecka 16, PL 31–531 Krakow, Poland.

References

- Ross R. Atherosclerosis: an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson GK. Immune mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1876–1890. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder CJ, Chang MK, Shaw PX, Miller YI, Hartvigsen K, Dewan A, Witztum JL. Innate and acquired immunity in atherogenesis. Nat Med. 2002;8:1218–1226. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselaar SE, Kakkanathu PX, Daugherty A. Lymphocyte populations in atherosclerotic lesions of apoE −/− and LDL receptor −/− mice. Decreasing density with disease progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:1013–1018. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Leung C, Schindler C. Lymphocytes are important in early atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:251–259. doi: 10.1172/JCI11380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Stemme S, Hansson GK. Evidence for a local immune response in atherosclerosis. CD4+ T cells infiltrate lesions of apolipoprotein-E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:359–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon CA, Blachowicz L, White T, Cabana V, Wang Y, Lukens J, Bluestone J, Getz GS. Effect of immune deficiency on lipoproteins and atherosclerosis in male apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1011–1016. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Nicoletti A, Elhage R, Hansson GK. Transfer of CD4(+) T cells aggravates atherosclerosis in immunodeficient apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Circulation. 2000;102:2919–2922. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.24.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst R, Xu Q, Willeit J, Waldenberger FR, Weimann S, Wick G. Immunology of atherosclerosis: demonstration of heat shock protein 60 expression and T lymphocytes bearing alpha/beta or gamma/delta receptor in human atherosclerotic lesions. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1927–1937. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melian A, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Porcelli SA. CD1 expression in human atherosclerosis: a potential mechanism for T cell activation by foam cells. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:775–786. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhage R, Arnal JF, Pierragi M-T, Duverger N, Fiévet C, Faye JC, Bayard F. Estradiol-17β prevents fatty streak formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2679–2684. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhage R, Clamens S, Reardon-Alulis C, Getz GS, Fiévet C, Maret A, Arnal JF, Bayard F. Loss of atheroprotective effect of estradiol in immunodeficient mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:462–465. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen N, Sawada S, Littman DR. Regulated expression of human CD4 rescues helper T cell development in mice lacking expression of endogenous CD4. EMBO J. 1993;12:1547–1553. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung-Leung WP, Schilham MW, Rahemtulla A, Kundig TM, Vollenweider M, Potter J, van Ewijk W, Mak TW. CD8 is needed for development of cytotoxic T cells but not helper T cells. Cell. 1991;65:443–449. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P, Clarke AR, Rudnicki MA, Iacomini MA, Itohara S, Lafaille JJ, Wang L, Ichikawa Y, Jaenisch R, Hooper ML. Mutations in T-cell antigen receptor genes alpha and beta block thymocyte development at different stages. Nature. 1992;360:225–231. doi: 10.1038/360225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille J, Iacomini J, Nelson A, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Farr A, Tonegawa S. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 1993;72:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duez H, Chao YS, Hernandez M, Torpier G, Poulain P, Mundt S, Mallat Z, Teissier E, Burton CA, Tedgui A, Fruchart JC, Fiévet C, Wright SD, Staels B. Reduction of atherosclerosis by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha agonist fenofibrate in mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48051–48057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Paulsson G, Stemme S, Hansson GK. Hypercholesterolemia is associated with a T helper (Th) 1/Th2 switch of the autoimmune response in atherosclerotic apo E-knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1717–1725. doi: 10.1172/JCI1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinski W, Ord VA, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Steinberg D, Witztum JL. ApoE-deficient mice are a model of lipoprotein oxidation in atherogenesis: demonstration of oxidation-specific epitopes in lesions and high titers of autoantibodies to malondialdehyde-lysine in serum. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:605–616. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B, Shires J, Theodoridis E, Pollitt C, Wise EL, Tigelaar RE, Owen MJ, Hayday AC. The inter-relatedness and interdependence of mouse T cell receptor gammadelta+ and alphabeta+ cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon CA, Blachowicz L, Lukens J, Nissenbaum M, Getz GS. Genetic background selectively influences innominate artery atherosclerosis: immune system deficiency as a probe. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1449–1454. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000079793.58054.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massberg S, Brand K, Gruner S, Page S, Muller E, Muller I, Bergmeier W, Richter T, Lorenz M, Konrad I, Nieswandt B, Gawaz M. A critical role of platelet adhesion in the initiation of atherosclerotic lesion formation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:887–896. doi: 10.1084/jem.20012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y, Schober A, Forlow SB, Smith DF, Hyman MC, Jung S, Littman DR, Weber C, Ley K. Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Nat Med. 2003;9:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry-Lane PA, Patterson C, van der Merwe M, Hu Z, Holland SM, Yeh ET, Runge MS. p47phox is required for atherosclerotic lesion progression in ApoE(−/−) mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1513–1522. doi: 10.1172/JCI11927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedlock DJ, Whitmire JK, Tan J, MacDonald AS, Ahmed R, Shen H. Role of CD4 T cell help and costimulation in CD8 T cell responses during Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 2003;170:2053–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyznik AJ, Sun JC, Bevan MJ. The CD8 population in CD4-deficient mice is heavily contaminated with MHC class II-restricted T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:559–565. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig B, Freigang S, Jaggi M, Kurrer MO, Pei YC, Vlk L, Odermatt B, Zinkernagel H, Hengartner H. Linking immune-mediated arterial inflammation and cholesterol-induced atherosclerosis in a transgenic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12752–12757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220427097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat Z, Gojova A, Brun V, Esposito B, Fournier N, Cottrez F, Tedgui A, Groux H. Induction of a regulatory T cell type 1 response reduces the development of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation. 2003;108:1232–1237. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089083.61317.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions, and fallacies. Immunol Today. 2000;21:573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupin E, Nicoletti A, Elhage R, Rudling M, Ljunggren HG, Hansson GK, Berne GP. CD1d-dependent activation of NKT cells aggravates atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:417–422. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonuleit H, Schmitt E. The regulatory T cell family: distinct subsets and their interrelations. J Immunol. 2003;171:6323–6327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri G, Nicoletti A, Poirier B, Hansson GK. Protective immunity against atherosclerosis carried by B cells of hypercholesterolemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:745–753. doi: 10.1172/JCI07272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major AS, Fazio S, Linton MF. B-lymphocyte deficiency increases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1892–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000039169.47943.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Kools JJ, Taylor WR. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension accelerates the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:448–454. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1605–1612. doi: 10.1172/JCI7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Martin-McNulty B, Freay AD, Sukovich DA, Halks-Miller M, Li WW, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Morser J, Dole WP, Deng GG. Angiotensin II increases urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression and induces aneurysm in the abdominal aorta of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1455–1464. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in LDL receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]