A 47-year-old Caucasian woman came to the emergency department at Baylor University Medical Center complaining of a 3-week history of sinus congestion and drainage with a sore throat. Her primary care physician had prescribed a 5-day course of azithromycin 250 mg. Since she did not improve, the doctor prescribed moxifloxacin and steroids. Symptoms improved temporarily but then returned. She sought care in the emergency department after two episodes of coughing with hemoptysis. She also complained of generalized malaise, myalgias, headache, nausea, anorexia, and left chest wall tenderness. The patient denied exposure to tuberculosis or sick contacts.

Her previous medical history was unremarkable. Her only regular medication was atorvastatin, 10 mg daily, for hypercholesterolemia. She denied using alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs.

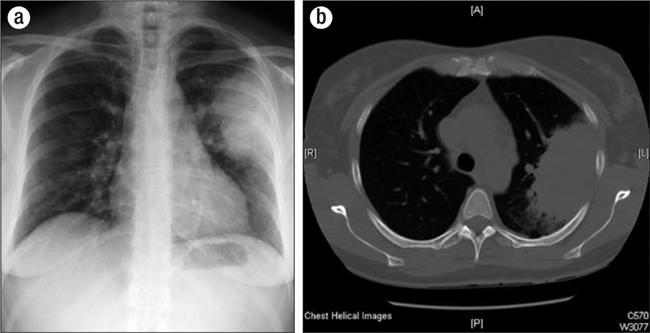

Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing patient. She had mild bibasilar crackles in her lungs. Her vital signs and results of the remaining physical examination were normal. Laboratory tests obtained in the emergency department are shown in Table 1. A radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scan of her chest revealed a large confluent density in the periphery of the left midlung and two smaller nodules in the right midlung as well as multiple reactive mediastinal lymph nodes (Figure 1). A peripheral blood smear showed hypochromasia, polychromasia, and rouleaux.

Table 1.

Significant laboratory test results

| Test | Result |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 134 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 96 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 19 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.9 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.4 |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 5.1 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 122 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 8.6 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 26.3 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 86 |

| Urinalysis | 1+ protein, 3+ blood, frequent epithelial cells, 10–15 red blood cells, many bacteria |

Figure 1.

(a) Chest radiograph showing a confluent density in the left midlung and two smaller pulmonary nodules in the right midlung. (b) Computed tomography scan showing the same nodular findings with the addition of mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

Her presenting problems were hemoptysis with an abnormal chest radiograph and CT scan, upper respiratory symptoms, renal insufficiency, hematuria, proteinuria, anemia, hyponatremia, and hypoalbuminemia. A differential diagnosis that encompasses these symptoms includes forms of glomerulonephritis associated with systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Goodpasture syndrome.

The middle lobe lung infiltrate increased the probability of an atypical pneumonia. However, the infectious disease workup was negative. Urinalysis revealed the presence of red cell casts. Analysis of serum and urine protein electrophoresis for proteinuria revealed only acute-phase changes without evidence of any monoclonal spike. Positive rheumatologic test results included the following: antinuclear antibody titer, 1:160 with a speckled fluorescence pattern; rheumatoid factor titer, 1:80; and cytoplasmic–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (C-ANCA) titer, 1:64.

Bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsies showed mixed inflammatory infiltrates but no evidence of malignancy. Studies showed no Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, virus, or fungus. A kidney biopsy showed acute necrotizing and pauci-immune acute crescentic glomerulonephritis consistent with Wegener granulomatosis 1 (Figure 2). Renal biopsy immunofluorescence was negative for immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgA, IgM, complement, and kappa and lambda light chains, with normal albumin backgrounds. Electron microscopy showed no electron-dense deposits. Light microscopy showed perivascular granulomas, which are typically seen in lung or sinus tissue biopsies but rarely in kidney biopsies.

Figure 2.

Results of the patient's kidney biopsy. (a) The hypercellular and proliferative glomeruli, showing crescent formation (arrow). (b) The granuloma with a giant cell (arrow), encompassed by several arterioles and vascular areas.

These findings led us to a diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis. The treatment included methylprednisolone 1 gm intravenously (started before the kidney biopsy) and then prednisone 80 mg orally, cyclophosphamide, and sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim after we determined the definitive diagnosis. The patient tolerated the treatment well, leading to her subsequent discharge from the hospital. She continues outpatient follow-up care with a nephrologist to monitor treatment with cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Shortly after discharge, her creatinine level decreased to 1.5 mg/dL; currently, her creatinine level is 1.0 mg/dL, and she continues to improve.

Wegener granulomatosis, or granulomatous vasculitis, is a disease that produces inflammation of the medium and small arteries and venules (2–4). Necrotizing and crescentic changes are found in the glomeruli (1). The process typically affects the upper and lower airways and kidneys.

The prevalence of the disease is about 3 in 100,000, with a slightly higher prevalence in men than in women (3:2). The peak incidence of the disease is at 50 to 60 years of age.

This patient presented with the classic clinical triad of Wegener granulomatosis: upper respiratory, pulmonary, and kidney involvement (2, 3). Other organ systems that can be affected include the joints, eyes, skin, central nervous system, and, less commonly, the gastrointestinal tract, parotid gland, heart, thyroid, liver, and breast (5–7) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Common presenting symptoms of Wegener granulomatosis

| • Persistent rhinorrhea |

| • Purulent/bloody nasal discharge |

| • Oral/nasal ulcers |

| • Polyarthralgia/myalgias |

| • Sinus pain |

| • Earaches/hearing loss |

| • Hoarseness/stridor |

| • Hemoptysis/cough/dyspnea |

| • Nodules and opacities seen on chest radiograph |

| • Nonspecific complaints: fevers, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, malaise |

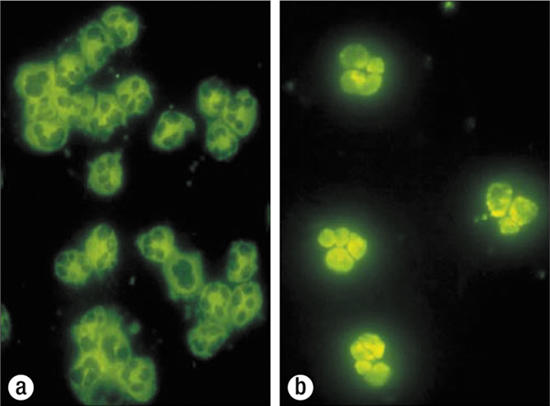

Wegener granulomatosis is considered a probable autoimmune disorder because of the frequent presence of high-titer antibodies against neutrophilic peptides (ANCA). Most characteristic is C-ANCA directed against proteinase 3 present in the primary granules of neutrophils and monocytes. These antibodies are important for the diagnosis of the disease and may also play a major pathogenic role (4, 8–10). Experimental studies indicate that they can cause tissue damage and vasculitis (Figure 3). Ninety percent of patients with active generalized disease are ANCA positive. However, in patients with milder, limited forms of the disease, the ANCA test may be negative up to 40% of the time (10). A positive perinuclear (P)-ANCA result is less specific. Other frequent but nonspecific laboratory findings include leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a normocytic, normochromic anemia (11).

Figure 3.

Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) under fluorescence. (a) In C-ANCA (cytoplasmic), the cytoplasm lights up. (b) In P-ANCA (perinuclear), a green halo appears on the cytoplasm and the nucleus lights up.

A tissue biopsy is essential for the definitive diagnosis of Wegener granulomatosis. Upper respiratory tract biopsies show acute and chronic inflammation with granulomatous changes. Kidney biopsies typically show segmental necrotizing pauci-immune and often angiocentric glomerulonephritis (1). Lung biopsies show vasculitis and granulomatous inflammation.

Confirmation of the diagnosis is important because therapy is often very toxic. Initial therapy generally consists of cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids (12). This regimen is maintained until the patient is in stable remission, usually 3 to 6 months. Various alternative regimens include 1) intravenous monthly cyclophosphamide instead of daily, oral cyclophosphamide; 2) methotrexate instead of cyclophosphamide in patients with mild disease, limited bone marrow reserve, or bladder toxicity; and 3) plasmapheresis, especially when anti–glomerular basement membrane antibodies are present or when severe pulmonary hemorrhage occurs (13).

Maintenance therapy is usually given for 12 to 18 months after the initial remission to prevent relapse. Cyclophosphamide is continued for approximately 12 months. However, corticosteroids are not shown to have any added benefit in maintenance therapy; thus, they should be tapered rapidly after the disease stabilizes (12). Several drugs are given for prophylaxis for potential side effects from treatment medications (14, 15) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Medications used for treatment side effects

| Medication | Indication |

| Leuprolide | Amenorrhea |

| Mesna | Bladder toxicity and cancers from cyclophosphamide irritation |

| Nystatin | Oral and fungal infections |

| Histamine-2 receptor antagonists and proton-pump inhibitors | Gastritis that can occur with highdose steroids |

| Vitamin D, calcium, and bisphosphonates | Osteoporosis with chronic steroid use |

| Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim | Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia prophylaxis |

Most adverse, nonfatal outcomes are related to the treatment of Wegener granulomatosis. These include side effects from glucocorticoids, increased risk of malignancy, and progressive organ failure. Patients with Wegener granulomatosis have an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, probably because of the nature of the vasculitis. Progressive renal failure with kidney involvement and respiratory failure with pulmonary involvement can occur. Untreated patients have a low survival rate of only 20% at 2 years. However, the 2-year survival rate for treated patients is about 90%.

References

- 1.Haas M, Eustace JA. Immune complex deposits in ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis: a study of 126 cases. Kidney Int. 2004;65(6):2145–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manganelli P, Fietta P, Carotti M, Pesci A, Salaffi F. Respiratory system involvement in systemic vasculitides. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(2 Suppl 41):S48–S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duna GF, Galperin C, Hoffman GS. Wegener's granulomatosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995;21(4):949–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo P, Stone JH. The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitides. Am J Med. 2004;117(1):39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper SL, Letko E, Samson CM, Zafirakis P, Sangwan V, Nguyen Q, Uy H, Baltatzis S, Foster CS. Wegener's granulomatosis: the relationship between ocular and systemic disease. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(5):1025–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daoud MS, Gibson LE, DeRemee RA, Specks U, el-Azhary RA, Su WP. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(4):605–612. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdogu H, Boga C, Bolat F, Ertorer ME. Wegener's granulomatosis with a possible thyroidal involvement. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(6):956–958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans J, Andrassy K, Csernok E, Gaskin G, Lesavre P, Ludemann J, Rasmussen N, Sinico RA, Wiik A, van der Woude FJ, EC/BCR Project for ANCA Assay Standardization Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. Kidney Int. 1998;53(3):743–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch X, Guilabert A, Font J. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Lancet. 2006;368(9533):404–418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan MD, Harper L, Williams J, Savage C. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm–associated glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(5):1224–1234. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Leavitt RY, Hallahan CW, Lebovics RS, Travis WD, Rottem M, Fauci AS. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(6):488–498. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White ES, Lynch JP. Pharmacological therapy for Wegener's granulomatosis. Drugs. 2006;66(9):1209–1228. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy JB, Hammad T, Coulthart A, Dougan T, Pusey CD. Clinical features and outcome of patients with both ANCA and anti-GBM antibodies. Kidney Int. 2004;66(4):1535–1540. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ognibene FP, Shelhamer JH, Hoffman GS, Kerr GS, Reda D, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: a major complication of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(3 Pt 1):795–799. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somers EC, Marder W, Christman GM, Ognenovski V, McCune WJ. Use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for protection against premature ovarian failure during cyclophosphamide therapy in women with severe lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(9):2761–2767. doi: 10.1002/art.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]