Abstract

Purpose

Eighty-five to ninety percent of cancer incidence is attributable to lifestyle choices, such as diet, life habits such as smoking, and environmental factors. Culture is the single force most influential on lifestyles. This paper provides a framework to understand the potential contribution of sociocultural factors to cancer control.

Methods

This literature review of culture and cancer control provides a perspective on Asian American populations. Culture is defined in a manner that enables researchers and practitioners to begin to focus on the fundamental elements of culture that directly influence health behavior.

Findings

Only four studies were found that address sociocultural factors in cancer control for Asian Americans. Each of these studies found significant variations in the response to cancer than Euro-American populations. Only mainstream researchers or practitioners, who are knowledgeable enough about Asian American cultures to be sensitive to these differences, would recognize these variations.

Conclusions

The widening disparities in cancer outcomes between Asian- and Euro-Americans challenges the current research and practice paradigms for cancer control. A Cultural Systems Approach would strengthen future studies. This paradigm requires multi-level analyses of individuals and populations within specific contexts in order to identify culturally based strategies to improve practice along the cancer care continuum.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 30 years, dramatic advances have been made in understanding the cell biology of cancer and the genetic changes involved in oncogenesis resulting in significant improvement in health status outcomes. These advances, however, have not benefited Asian Americans to the same degree as Euro-Americans. This paper suggests that to accelerate the movement of Asian Americans to fully participate in the advances in cancer care, changes are required on two levels in cancer control. First, greater resources must be directed toward social and behavioral research, and second, better strategies must be developed to study the effects of cultural differences on health behavior.

Currently, only about 5%–10% of cancers are known to be due to inherited genetic abnormalities. The remaining 90% of cancers is attributable to lifestyle factors1. Lifestyles emanate from cultural beliefs, values and practices. International studies show that the incidence rates of cancers appear to be about the same worldwide, but the types of the cancers differ considerably2. Studies of immigrants show that their cancer rates and types begin to change in as little as ten years after arrival to mirror those of the host culture3. For example, Asian women in Asia have one-quarter to one-half the rates of breast cancer as white American women, but after one generation in the U.S., the rates of breast cancer for Asian American women approach those of white women4. Thus culture, which informs lifestyle differences, such as practices that determine diet, exercise patterns, weight norms, work environments, birth rates, age at first birth, and health-seeking patterns, plays a major role in health promotion and maintenance.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES ON HEALTH OUTCOMES

Culture affects both the risk factors for cancer as well as the meaning of the disease by establishing norms of behavior and providing guidance for its members to respond emotionally, cognitively, and socially to this disease. Thus cultural beliefs and practices affect cancer care along the entire disease continuum: from prevention and early detection, treatment choices and adherence rates, management of side effects such as pain and its control, appropriate psychosocial support, rehabilitation efforts, survivorship issues, hospice use, and effective end of life care.

Asian Americans (AAs) make up over 4% of the population nationwide and about 12% of California’s population5, yet very little is known about their experience with cancer. AAs constitute a relatively “new” minority in the U.S. in relation to national visibility, and although the model minority myth is slowly being corrected6, the landscape of how cancer impacts the AA population is still essentially unknown in the literature or to mainstream program and policy planners.

Practitioners and community-based organization leaders know the specific problems that exist in their communities, and, notably, have developed creative and effective means to address these needs. Their efforts, however, have been limited by inadequate funds and trained staff to test and publish their strategies.

One of the major barriers to widespread appreciation of the efforts and effectiveness of community-based organizations has been the lack of recognition of the AA cancer problem by the larger public or scientific communities. Conferences such as this, and the Ohio State University Minton Memorial Lecture, provides the necessary forum to present and discuss some of the major steps needed to guide the formulation of culturally based research and practice to reduce the increasing burden of cancer in the Asian American community.

Asian American Cancer Data

The only data on cancer in the diverse groups of AAs are in the area of prevention, early detection (e.g., Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey), and limited incidence and mortality figures2, 7–8. As an aggregate group, AAs, have the lowest screening rates for cancer of all ethnic populations9. Reasons for this poor screening effort are explained by structural and conceptual barriers to cancer care10. The major structural barriers to cart tend to be universal: availability, accessibility, acceptability, accountability, risks/benefit calculations for utilization, lack of adequate insurance, and lack of knowledge about the benefits of screening or where to go to obtain services. The major conceptual barriers are often more culturally specific: concepts of health, differing models of physiology, body concepts and body image, and differing concepts regarding the meaning of cancer and problems caused by the disease.

Unlike other ethnic groups in the U.S., only a few studies exists on the impact of the disease on the responses of AAs to treatment, pain control, emotional and social impact of cancer, coping strategies, effective social support, issues related to end of life care, communication regarding the diagnosis and prognosis, and/or treatment decision making patterns.

Only one ethnographic study of breast screening has been publsihed with AA women. Mo11 studied the meaning of breast cancer in Chinese American women and found that cultural differences significantly constrained women from early detection and treatment. Other studies compared the coping styles to cancer and its treatment between Japanese-Americans and Anglo-Americans12. The results showed that although both groups coped in a positive manner to the disease experience, not only was each style of adaptation and coping culturally identifiable, most notably, each would have been inappropriate and maladaptive for the other group. The Japanese-Americans’ response was one of endurance - to withstand the onslaught of the disease with strength, but quietly and with minimal discussion with family or friends. In contrast, the Anglo-Americans responded with the idiom of fighting an enemy. Their demeanor was one of assertiveness and verbalized strength. The social support network for the Anglo-American women involved a wide circle of confidantes, including small children, but the networks of the Chinese- and Japanese-American women were less than one-third that of the Anglo-American women13.

A third study compared the responses of Chinese-American, Japanese-American, and Euro-American women. Post-breast cancer Chinese-American women presented with later stage disease than either the Japanese-or Euro-American women. Fewer AA women chose adjuvant therapy, and breast conserving therapy. This finding is consistent with national studies as well. Notably, the Asian women appeared to have more emotional difficulty with the disease due to cultural constraints than the Euro-American women13–14.

Other data show that Native Hawaiian women have the highest mortality rates from breast cancer of all AA and Pacific Islander women. Yet, their 5 year survival rates are not significantly different15. The potential protective cultural factors that enabled these Native Hawaiian women to survive longer with advanced disease may be attributable to cultural beliefs and practices, but have not been explored16.

Understanding the significance of cultural influences on health beliefs and behaviors is fundamental to the development of successful cancer research and service programs for AAs. Culture is the interrelated system of beliefs, values and practices that arise from a particular historical and geographical situation of a people that creates both environmental resources and constraints on their technologic, economic, and social structures17. This dynamic and reactive complex of material and conceptual culture is passed from one generation to the next in a socialization process that is specifically designed to ensure the survival and well-being of its members. The adaptive and protective factors of cultural differences should also be a focus of study.

Culture, then, becomes a tool that its members use to make sense of the chaos around them and to take appropriate action to alleviate the discomforts, dangers and sicknesses. Through beliefs, values and rituals, it makes the unpredictable and inevitably uncontrollable events, such as sickness and death, predictable and controllable. Culture takes the abstract ideas of the group’s worldview and puts them into tangible, understandable beliefs and behaviors for its members to use to sustain and create meaning in their lives. As a member of a cultural group, one learns prescribed emotional reactions as well as the proper behavioral responses that communicate caring, safety, and social support. The two major functions of culture are the integrative component, which is composed of beliefs and values that give an individual a sense of identity and a sense of security, and the prescriptive component which contains rules for correct and moral behavior. Members of the cultural or ethnic group weave these two functions together to form an integrated whole fabric that they wrap around themselves for security and a sense of belonging and identity.

Research Paradigm

The cross-cultural validity of the health research paradigm currently used as well as the validity of standardized measures are questionable. The dominant research paradigm employed in ethnic minority health assessment and health promotion identifies socio-economic status as the most powerful indicator of health status and care utilization. The contribution of culture is usually not discussed in great detail. Yet the widening disparity in health outcomes challenges these data. The terms race, culture and ethnicity are erroneously used interchangeably, and thereby creates a major barrier to reducing the health disparities among minority ethnic populations. Race, culture and ethnicity are typically measured as dichotomous variables with proxy indicators, such as language, place of birth, and/or the Federally designated racial groups - all of which are poor measures of culture or ethnicity.

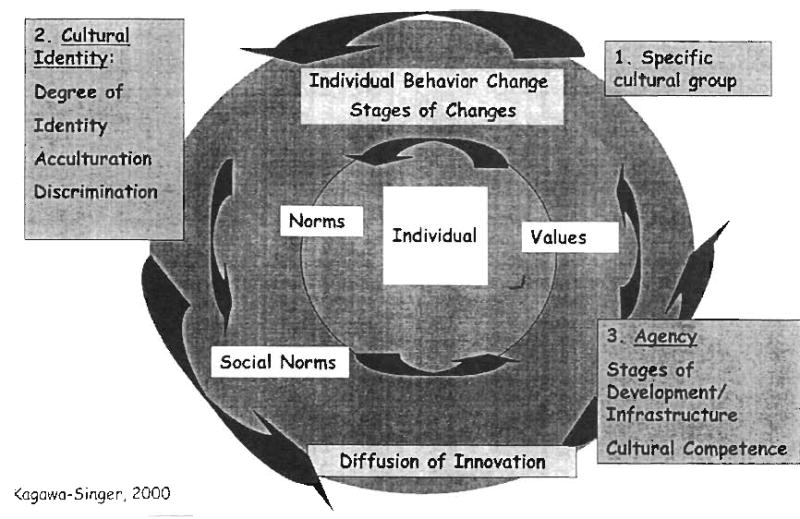

In my own work, I apply an ecologic model, a Cultural Systems Approach, to design interventions to reduce disparities in cancer incidence, morbidity and mortality within the diverse AAPI groups, and to promote their health and quality of life (See Figure 1). The strategy I use is to expand the theoretical basis of the influence of the concepts of culture and ethnicity on health, and refine the methodological use of these concepts. My premise is that the unidimensional concepts of race/culture/ethnicity used in most cross-cultural studies of health are too restrictive to account for the range of variation between, as well as within, particular ethnic groups. If the construct of culture were operationalized more comprehensively in a multidimensional manner, the construct would explain a substantial portion of the variance in health outcomes for minority populations, and importantly, suggest more salient factors to use for effective health promotion strategies in these communities. This perspective operationalizes culture as a dynamic, continuous concept that varies individually as well as within group, and within blended borders in a multicultural society.

Figure 1.

Cultural Systems Approach

This anthropological, ecologic definition of culture contextualizes the beliefs, values, and practices of a population group within a geographic as well as social and political environmental niche. This dynamic, multi-level systems model of culture situates individual behavioral choices within the larger, social, economic, and political environments of communities. By using this more scientifically grounded construct of culture in health research, both the positive and negative adaptive strategies of cultural groups are more likely to be captured and employed in the design of health promotion activities.

The erroneously assumed universality of core values within the Euro-American paradigm of individuality and autonomy that are fundamental to most health research and practice also pose barriers for AA. I have investigated cultural variations and found significant variances in conceptualizations, constructs, and measurement of communication styles, gender dynamics, social support, and concepts in mental health such as self-esteem, ethnic identity, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in AA populations. Chung and Kagawa-Singer18 found that the report of psychological distress of Southeast Asian refugees did not fit diagnostic categories in Western nosology. Through factor analysis, we showed that the Southeast Asian refugees expressed distress through a one-factor construct compared to the three-factor construct for Euro-American clients. Moreover, both pre- and post-migration and gender differences were significant. We provided clinical and research recommendations based on our findings to modify the Western designed psychotherapeutic strategies to be more responsive to Southeast Asian distress models.

The work of my colleagues and I13–14 in breast cancer care for AA women document the culturally informed nature of health behavior for Asian American and Caucasian women. We also triangulated data from qualitative interviews and standardized tools to capture cultural nuances, and found that if the results of the standardized tools were taken as equally valid for Japanese- and Chinese-American women, potential psychological distress would be missed, and these women would suffer unnecessarily.

As a practitioner, I recognize that cultural competency in clinical practice is imperative. I have chosen various population groups and cancers in order to highlight how cultural differences affect responses to sickness and disease. I have demonstrated the limited cross-cultural applicability of concepts such as Western psychological counseling techniques for treatment, and for end-of-life care, and suggest more culturally based strategies to improve practice along the cancer care continuum.

Through the AANCART program, we will be able to promote research on the risk factors that affect 90% of the variance in cancer causation. We will make major strides in reducing the burden of cancer in the Asian American population, and I am thrilled and honored to be a part of this effort.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.DeVita V, Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. J.B. Lippincott Company; Philadelphia.: 1989. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levi F, et al. Worldwide patterns of cancer mortality, 1990–1994. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999;8(5):381–400. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziegler RG, et al. Migration patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian-American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(22):1819–27. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.22.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagawa-Singer M, Maxwell A. Breast cancer screening in Asian and Pacific Islander American Women, in Preventing and Controlling Cancer in the Americas: Canada, United States, and Mexico. In: Weiner D, editor. Greenwood Publishers; Los Angeles: 1998. pp. 147–66. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Census of Populations. U.S. Department of Commerce; Washington D.C.: 1990. Asian and Pacific Islanders in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MS, Jr, Hawks BL. A debunking of the myth of healthy Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Am J Hlth Prom. 1995;9(4):261–8. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1997. National Cancer Institute; Washington D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society; Atlanta.: 1998. Cancer facts and figures for minority Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Cancer Society. Atlanta.: Cancer Facts and Figures- 1997. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins CNH, Kagawa-Singer M. Cancer, in Confronting critical health issues of Asian and Pacific Islander Americans. In: Zane NWS, Takeuchi DT, Young KNJ, editors. SAGE Publication; Thousand Oaks: 1994. pp. 105–47. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mo B. Modest, sexuality, and breast health in Chinese-American women. Cross-Cultural Medicine: A decade later (special issue) 1992 Sept;157:260–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kagawa-Singer M. University of California, Los Angeles; Los Angeles: 1988. Bamboo and oak: Differences in adaptation to cancer between Japanese-American and Anglo-American patients, in Anthropology; p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wellisch D, Kagawa-Singer M, Reid S, et al. An exploratory study of social support: a cross-cultural comparison of Chinese-, Japanese-, and Anglo-American breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8(3):207–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199905/06)8:3<207::AID-PON357>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagawa-Singer M, Wellisch DK, Durvasula R. Impact of breast cancer on Asian American and Anglo American women. Culture Med Psychiatry. 1997;21(4):449–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1005314602587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 1991. Cancer facts and figures for minority Americans. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer: A randomized prospective outcome study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):527–33. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond P. 2 ed. Vol XIV. New York; McMillan Co: 1978. An introduction to cultural and social antrhopology. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung R-YC, Kagawa-Singer M. Predictors of psychological distress among Southeast Asian refugees. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;36(5):631–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90060-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]