Abstract

Purpose

We summarized previous and ongoing cancer control research among Cambodian immigrants in Washington.

Methods

A literature review of articles and published abstracts was conducted.

Findings

Cambodian Americans have a limited understanding of Western biomedical concepts, and low levels of cancer screening participation.

Conclusions

Culturally appropriate cancer control interventions for Cambodian Americans should be developed, implemented, and evaluated.

INTRODUCTION

By 1990, census data indicated there were 150,000 Cambodians living in the U.S.1 The majority of Cambodians were forced to flee their country because of the political and personal persecution imposed by the Khmer Rouge regime during the mid-1970s and were relocated to North America from refugee camps in Thailand and the Philippines2. Cambodia is a largely agrarian society and, before the revolutionary period, the majority of Cambodians lived in rural or semirural settings3. Therefore, immigrants from Cambodia are particularly unfamiliar with Western culture, institutions, and biomedical concepts of early detection4. Further, compared to other Asian American groups, Cambodians are both socioeconomically disadvantaged (43% of households are below the Federal poverty level) and linguistically isolated (only 27% speak fluent English)1.

There is little published information concerning the health promotion and disease prevention behavior of Cambodian Americans. This brief report summarizes cancer control initiatives targeting the Cambodian community in Seattle, Washington. These initiatives involve investigators from the Seattle site of the Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research, and Training (AANCART) program as well as other colleagues from Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington. Our previous and ongoing cancer control research addresses Papanicolaou (Pap) testing, hepatitis B (which is the etiologic cause of most liver cancers in Asian populations), and breast cancer screening5. Much of this work has involved active collaboration with the Seattle Cambodian Women’s Association.

Pap Testing

Our five-year project, Cervical Cancer Control in a Cambodian Population, was funded by the National Cancer Institute in 1996. The research objectives are as follows: obtain qualitative and quantitative information about the cervical cancer screening behavior of Cambodian Americans; develop a culturally appropriate, neighborhood-based Pap testing intervention for Cambodian women; and conduct a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness of the intervention program6.

We completed 42 unstructured interviews with Cambodian American women. In addition, to verify information collected during our one-to-one interactions, we conducted four focus groups6–8. The qualitative data collection effort allowed us to identify several cultural issues that could potentially influence women’s use of Pap testing. For example, it revealed a complex traditional model of reproductive health and illness. The post-partum period (sor sai kjai) is a critical time in a woman’s life and chronic health problems can be prevented by following certain observances (e.g., avoiding heavy lifting) after childbirth. As part of the traditional model, women’s marital status is used as a marker for sexual activity and possible exposure to detrimental exogenous forces (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases); unmarried women are presumed to be sexually inactive and, consequently, not at risk for gynecologic problems. We also found that cancer is poorly understood and often considered synonymous with terminal illness. Finally, surgery (e.g., hysterectomy) is considered to be an unnatural intervention into the flow of blood and energy through the body, and is feared because of perceptions about high mortality and complication rates (based on experiences in Cambodia).

The qualitative data were used to guide the development of a quantitative survey instrument as well as components of our intervention program. For example, many of the findings were incorporated into the script of our Khmer-language video entitled The Preservation of Traditions7–8. This video provides information about biomedical concepts, cervical cancer, and barriers to Pap testing, but also recognizes Cambodian beliefs about disease and traditional health practices. Key messages that are used in action statements include: Cambodian women have a long history of health promotion through traditional dietary and behavioral recommendations and inhibitions; and Pap testing is an American method of maintaining health that can be added to the rich Cambodian traditions. The characters portrayed in the video include a non-acculturated older Cambodian woman, a bicultural community leader, and two younger, relatively acculturated outreach workers from a local clinic. Examples of ways in which the qualitative data were used to guide the video content are provided in Table 18.

Table 1.

Use of Qualitative Data Findings to Develop Video Content8

| Qualitative Finding | Video Content |

|---|---|

| Many Cambodians believe that traditional postpartum practices protect women from cervical disease | A community leader stresses that women’s health can be improved by adding American medical procedures, such as Pap testing, to traditional Cambodian methods |

| Most women believe that only sexually active, premenopausal women are at risk for cervical cancer | While discussing Pap testing with a group of community women, two outreach workers stress that screening is necessary for all women, including those who are older and without husbands. |

| Women are unfamiliar with early detection concepts and Pap testing | Outreach workers use a culturally appropriate (agrarian) analogy and a visual aid to explain the value of early detection to an older Cambodian woman |

| Pap tests are perceived as painful and uncomfortable | During a discussion with community women, an outreach worker explains that Pap tests should not be painful and do not harm the cervix |

| Women are embarrassed by gynecologic procedures, especially if they have to see male health care providers | Outreach workers help an older Cambodian women get an appointment with a female physician |

| Women are frightened of cancer and surgical treatment | An outreach worker describes how Pap testing can find any problems early so that a hysterectomy is not necessary |

| Lack of English proficiency is a barrier to preventive care | Clinic scenes show several interpreted medical encounters |

| Women are very motivated to stay healthy so that they can take care of their families | A community leader states that she has Pap testing so she can stay healthy and care for her children |

We conducted a baseline, community-based survey of Cambodian women aged 18 years or older during late 1997 and early 1998. Four hundred and thirteen women completed our questionnaire. Approximately one-quarter (24%) of the respondents had never had a Pap test, and less than one half (47%) had been screened recently (i.e., in the last two years). Table 2 gives the results from our multivariate analyses addressing predictors of cervical cancer screening participation. The following variables were positively associated with a history of at least one Pap smear: younger age, greater number of years since immigration, belief that Pap testing is necessary for postmenopausal women, prenatal care in the US, and physician recommendation. Women who believed in karma were less likely to have ever been screened for cervical cancer than those who did not. Six variables independently predicted recent screening: age; beliefs about regular checkups, cervical cancer screening for sexually inactive women, and the prolongation of life; having a female doctor; and a previous physician recommendation for Pap testing9.

Table 2.

Factors independently Associated with Cervical Cancer Screening Participation9

| Ever Screened

|

Recently Screened

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39 | 1.7 | 0.6–4.3 | 3.5 | 1.8–7.0 |

| 40–59 | 2.5 | 1.2–5.4 | 1.6 | 0.8–3.2 |

| 60+ | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 10+ years since immigration | 2.6 | 1.3–5.0 | ||

| Believed illness is a matter of karma | 0.5 | 0.2–0.8 | ||

| Believed women should have regular checkups | 2.6 | 1.2–5.8 | ||

| Believed Pap tests can prolong life | 1.8 | 1.1–3.0 | ||

| Believed Pap testing is necessary for sexually inactive women | 2.4 | 1.5–3.9 | ||

| Believed Pap testing is necessary for postmenopausal women | 2.5 | 1.4–4.4 | ||

| Ever received prenatal care in the U.S. | 2.1 | 1.1–4.3 | ||

| Regular physician | ||||

| Female | 2.3 | 1.4–3.8 | ||

| Male | 1.3 | 0.6–2.6 | ||

| No physician | 1.0 | |||

| Physician recommendation | 4.9 | 2.9–8.6 | 3.5 | 2.1–5.9 |

OR - odds ratio

CI - confidence interval

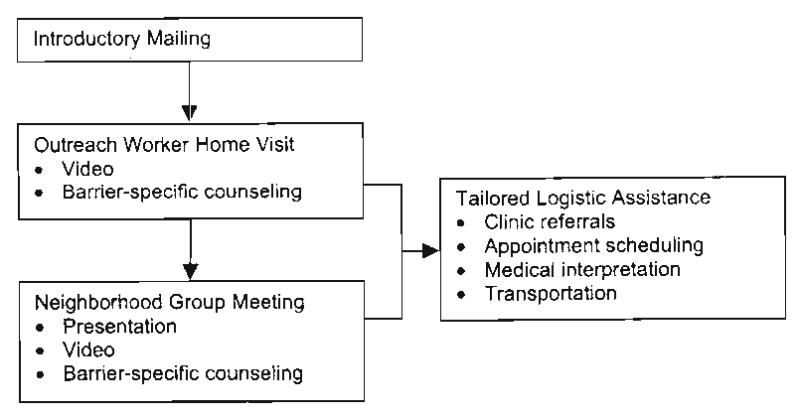

Our intervention approach is modeled on the Community House Calls program at Seattle’s county hospital (Harborview Medical Center). This program seeks to improve access to health care for refugee and other immigrant communities through the use of outreach workers (who act as medical interpreters as well as cultural mediators)10. Components of our outreach worker-based intervention program include home visits, small group meetings in neighborhood settings, use of the video, and tailored logistic assistance (Figure 1). A randomized group, controlled trial is being conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of this intervention approach. Women who participated in our community-based survey were assigned to small area neighborhoods which each include about 10 women. These small area neighborhoods were then randomized to intervention or control status. Our primary end-point of interest will be Pap testing utilization within the previous year; this end-point is being ascertained from the results of a follow-up survey as well as medical record verification of self-reported Pap testing behavior6.

Figure 1.

Intervention Program Overview6

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B among the Khmer assessed the utility of hepatitis B pamphlets designed for Cambodian refugees. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 34 Cambodian Americans (23 men and 11 women). This study found that while medical interpreters routinely translated hepatitis B as rauk tlaam (literally liver disease), the term was meaningless to 28 (82%) of the respondents. Further, it conveyed none of the chronicity and communicability intended by refugee health workers. In contrast, all respondents knew illnesses named after symptom complexes that include the symptoms of acute and chronic hepatitis, but do not refer to diseased organs. For example, the Cambodian patients were able to recognize hepatitis-like diseases such as khan leong (yellow illness) when jaundice, fatigue, anorexia, and abdominal discomfort were described during interviews11.

Breast Cancer Screening

Women who completed the Cervical Cancer Control in a Cambodian Population baseline survey were asked a series of questions addressing clinical breast examination (CBE); those women in the 40-plus age-group were also queried about their screening mammography behavior. Twenty-nine percent of our survey participants had never had a CBE and nearly three-quarters (74%) were not obtaining regular breast exams (screened in the previous year and planning to be screened in the next 12 months). One-third (33%) of the women aged 40 years and older had never received mammographic screening and 77% were not being screened regularly (mammography in the last two years and planning mammography in the next 24 months). In bivariate comparisons, correlates of at least one previous CBE included younger age, employment outside the home, greater number of years since immigration, and having a female physician. The following variables were associated with ever having had a mammogram: residence in the U.S. for 10 years or longer and seeing a woman doctor12.

Ethnomed

Ethnomed (http://www.hslib.Washington.edu/clinical/ethnomed) is an electronic database that contains medical and cultural information on refugee and immigrant groups (including Cambodians) in the Seattle area. The project was started (as part of the Community House Calls program) to bridge cultural and linguistic barriers to the effective delivery of medical care. The objective is to make information about culture, language, health, illness, and community resources directly accessible to physicians and other health care providers. It is designed to be a clinical tool that can be used by a practitioner in the few minutes before seeing a patient in clinic. For instance, before seeing a Cambodian patient, a provider can use a clinic computer terminal to access Ethnomed and read about common cultural issues that may complicate the patient’s medical management. Practitioners can also download linguistically appropriate patient education materials13.

Conclusion

In summary, cancer control research targeting the Cambodian community in Seattle, Washington includes qualitative and quantitative analyses of Pap testing barriers and facilitators; the design, implementation, and evaluation of a cervical cancer control intervention; a qualitative study of Cambodians’ understanding of hepatitis B; and a quantitative study of CBE and mammographic screening behavior. In addition, the Ethnomed electronic database could facilitate the dissemination of cancer-related research findings, clinical information, and patient education materials to health care providers who serve Cambodian (and other Asian) communities.

Our Pap testing qualitative results demonstrate the importance of using ethnographic methods during the development of intervention programs for less acculturated immigrant groups. For example, while many of the identified barriers to cervical cancer screening (e.g., concerns about embarrassment and discomfort) are shared by other socially disadvantaged populations, some (e.g., the belief that traditional post-partum practices protect women against gynecologic disease) are not8. Similarly, Hepatitis B Among the Khmer reinforces the importance of considering issues of translation and concepts of illness when developing survey questions and health education messages for non-English speaking communities11. Finally, our quantitative findings document low levels of cervical and breast cancer screening participation among Cambodian American women, and define factors associated with the use of early detection maneuvers9,12.

Acknowledgments

We especially acknowledge the contributions of the Cambodian Women’s Association as well as two key Cambodian staff members: Paularita Seng and Roeun Sam. In addition, we would particularly like to thank other members of our Seattle research group (Stephen Schwartz, Ph.D., and Yutaka Yasui, Ph.D.) and the project coordinators (Elizabeth Acorda at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Ann Marchand at Harborview Medical Center).

This work was supported by cooperative agreement CA86322 and grant CA70922 from the National Cancer Institute as well as funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.United States Department of Commerce. We the Asian Americans. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulig JC. Sexuality beliefs among Cambodians: implications for health professionals. Health Care Women Int. 1994;15:69–76. doi: 10.1080/07399339409516096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiernan B. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1993. Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: the Khmer Rouge, the United States, and the International Community. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uba L. Cultural barriers to health care for Southeast Asian refugees. Public Health Rep. 1992;107:544–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Bisceglie AM, Rustgi VK, Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Lotze ML. NIH Conference: hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:390–401. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor VM, Jackson JC, Schwartz SM, Yasui Y, Tu SP, Thompson B. Cervical cancer control in a Cambodian American Population. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health. 1998;6:368–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JC, Taylor VM, Chitnarong K, et al. Development of a cervical cancer control intervention for Cambodian American women. J Comm Health. 2000;25:359–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1005123700284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahloch J, Jackson JC, Chitnarong K, Sam R, Ngo LS, Taylor VM. Bridging cultures through the development of a cervical cancer screening video for Cambodian women in the United States. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:109–14. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor VM, Schwartz SM, Jackson JC, et al. Cervical cancer screening among Cambodian-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Bio Prev. 1999;8:541–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll-Jackson LM, Graham E, Jackson JC. Seattle: Harborview Medical Center; 1998. Beyond medical interpretation: the role of interpreter cultural mediators (ICMs) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson JC, Rhodes LA, Inui TS, Buchwald D. Hepatitis B among the Khmer: issues of translation and concepts of illness. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:92–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.012005292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu SP, Yasui Y, Kuniyuki A, Thompson B, Jackson JC, Taylor V. A population-based survey of breast cancer screening by Cambodian-American women; Presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine annual meeting; San Francisco. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson JC. Medical interpretation: an essential clinical service for non-English speaking immigrants. In: Loui S, editor. Handbook of immigrant health. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]