Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that the constitutively-active Q646C mutant of the ErbB4 receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits colony formation by human prostate tumor cell lines. Here we use ErbB4 mutants to identify ErbB4 functions critical for inhibiting colony formation. A derivative of ErbB4 Q646 that lacks kinase activity fails to inhibit colony formation by prostate tumor cells. Likewise, an ErbB4 Q646C mutant in the context of the CT-b splicing isoform fails to inhibit colony formation. Mutation of tyrosine 1056 to phenylalanine abrogates inhibition of colony formation whereas an ErbB4 mutant that lacks all of the putative sites of tyrosine phosphorylation except for tyrosine 1056 still inhibits colony formation. Given that tyrosine 1056 is missing in the CT-b isoform, these results suggest that phosphorylation of tyrosine 1056 is critical for function. Indeed, an ErbB4 mutant that lacks kinase activity but has a glutamate phosphomimic residue substituted for tyrosine 1056 inhibits colony formation. Finally, one-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping indicates that ErbB4 Q646C is phosphorylated on tyrosine 1056. These data suggest that phosphorylation of ErbB4 tyrosine 1056 is critical for coupling ErbB4 to prostate tumor suppression.

Keywords: ErbB4, prostate cancer, tumor suppressor, tyrosine phosphorylation sites, signal transduction, isoforms

Introduction

ErbB4 (HER4) is a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases. Other family members include the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR/ErbB1), ErbB2 (HER2/Neu) and ErbB3 (HER3) [1]. ErbB family receptors share several structural features. They contain an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a single-pass α-helical transmembrane region, and an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. Carboxyl terminal to the kinase domain are tyrosine residues that are phosphorylated upon ligand binding.

The peptide hormones of the Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) family are agonists for ErbB family receptors. There are approximately 20 different EGF-like peptides involved in ErbB receptor signaling [1, 2]. Several of these ligands can bind more than one receptor. For example, some members of the Neuregulin subfamily of ErbB4 ligands also bind EGFR or ErbB3 [1, 2]. Likewise, Betacellulin and Epiregulin bind both ErbB4 and EGFR [1, 2].

Ligand binding causes receptor dimerization, trans-phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine residues and coupling to downstream signaling events. A liganded ErbB receptor can homodimerize with another liganded ErbB receptor or heterodimerize with an unliganded ErbB receptor [1]. For example, ErbB4 ligands stimulate signaling by EGFR, ErbB2, and ErbB3 via heterodimerization with ErbB4 [1]. Consequently, use of ErbB4 ligands to study signaling events specific for ErbB4 may be problematic.

There are several transcriptional splicing isoforms of ErbB4 that differ in the extracellular juxtamembrane region and in a cytoplasmic region contained within the sites of tyrosine phosphorylation [3]. The canonical JM-a juxtamembrane isoform can be proteolytically cleaved in a two-step process that features the cleavage and release of the ErbB4 extracellular ligand-binding domain by TACE and the subsequent cleavage and release of the ErbB4 intracellular domain by γ-secretase [4, 5]. In contrast, the JM-b isoform is resistant to cleavage by TACE and the intracellular domain of this isoform cannot be generated and released from the cell plasma membrane [5]. The physiological significance of ErbB4 cleavage is that the ErbB4 intracellular domain can translocate to the nucleus. In MCF-7B cells, translocation of the ErbB4 intracellular domain facilitates STAT5a translocation to the nucleus and stimulation of STAT5a-dependent gene transcription [6]. However, this particular ErbB4 activity has not yet been observed in prostate cells.

The cytoplasmic or carboxyl-terminal isoforms differ in the presence (CT-a) or absence (CT-b) of a 16 amino acid sequence that includes Ser1046 through Gly1061. This region includes a putative WW domain binding sequence that begins at Pro1053 (PPAY) as well as a putative ErbB4 phosphorylation site (Tyr1056) that has been reported to bind the SH2 domain of the regulatory subunit of PI3 kinase [7-9]. Thus, the CT-a and CT-b isoforms may be quite different with respect to coupling to downstream signaling events and biological responses.

Overexpression, mutation, or deregulated signaling by ErbB1 and ErbB2 in tumor cells correlates with lesions that are more proliferative, invasive, chemoresistant, and are associated with a poorer patient prognosis [10]. The role that ErbB4 plays in tumorigenesis has yet to be well defined. ErbB4 is expressed in normal prostate tissue but most prostate tumors lack ErbB4 expression [11-13]. In several tumor types, ErbB4 expression correlates with less aggressive behavior and better patient prognosis [5, 14]. Thus, several groups have hypothesized that ErbB4 may be an epithelial tumor suppressor.

As stated earlier, one challenge in using ErbB4 ligands to test this hypothesis is that most ligands that activate ErbB4 also stimulate signaling by another ErbB receptor. Our laboratory has addressed this challenge by substituting a single cysteine residue for Gln646, His647, or Ala648 in the ErbB4 extracellular juxtamembrane region (Q646C, H647C, and A648C mutants). These mutants form disulfide-linked homodimers that exhibit constitutive, ligand-independent tyrosine phosphorylation [15]. Moreover, the ErbB4 Q646C mutant inhibits drug-resistant colony formation in plastic dishes by the DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cell lines [16]. This suggests that ErbB4 is a bona fide prostate tumor suppressor. Our lab as well as others have also reported that constitutively-active mutants of ErbB4 are capable of inhibiting breast cancer cell proliferation [17, 18]. This suggests that ErbB4 may be able to suppress growth of multiple types of epithelial cancers. Here we demonstrate that ErbB4 kinase activity is required for coupling of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant to inhibition of colony formation. Moreover, in the context of the CT-b splicing isoform, the ErbB4 Q646C mutant fails to inhibit colony formation. Indeed, the Tyr1056 residue that is absent in the CT-b is critical for inhibition of colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. Finally, the ErbB4 Q646C mutant is indeed phosphorylated on Tyr1056. Collectively, these data indicate that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 is critical for ErbB4 coupling to inhibition of colony formation.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids — The pLXSN retroviral expression vector is a generous gift from Daniel DiMaio (Yale University). Construction of the pLXSN-ErbB4, pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C, pLXSN-ErbB4 H647C, and pLXSN-ErbB4 A648C plasmids has been described previously [15]. The pLXSN-ErbB4 WT CT-b plasmid consists of the ErbB4 CT-b isoform [9] in the context of pLXSN. The pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C CT-b plasmid consists of the Q646C mutant in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 WT CT-b. The pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C Kin- plasmid consists of an ErbB4 mutant lacking kinase activity (K751M) in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C [17]. The LXSN-ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 plasmid consists of an ErbB4 mutant in which a phenylalanine residue is substituted for Tyr1056 in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C. The LXSN-ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 plasmid consists of an ErbB4 mutant in which a phenylalanine residue is substituted for Tyr1022, Tyr1150, Tyr1162, Tyr1188, Tyr1202, Tyr1242, Tyr1258, and Tyr1284 in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C. The pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 plasmid consists of an ErbB4 mutant in which a phenylalanine residue is substituted for Tyr1056 in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 [17]. The pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E plasmid consists of an ErbB4 mutant in which a glutamate residue is substituted for Tyr1056 in the context of pLXSN-ErbB4 Q646C Kin-.

All mutants were created by site directed mutatgenesis (QiukChange, Stratagene). Primer sequences are available upon request. All plasmids were sequenced and loss-of-function mutants were subjected to marker rescue analysis.

Cell Lines — DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate cancer cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Ψ2, PA317, and C127 cell lines are a generous gift from Daniel DiMaio (Yale University). Cell lines were cultured as described [15, 16, 19, 20] or according to vendor recommendations with the exception that Ψ2 cells were propagated in 10% Fetal Clone III (Hyclone) instead of fetal bovine serum.

Retrovirus Production — High titer amphotropic retrovirus stocks were generated as previously described [15, 16, 20, 21].

Colony Formation Assay — Inhibition of prostate tumor cell line colony formation on plastic by ErbB4 mutants was assayed essentially as previously described [15, 16, 19, 20]. Briefly, we infected C127, DU-145, and PC-3 cells with the recombinant amphotropic retrovirus stocks, selected for infected cells using 400 to 1100 μg/mL G418, and stained the emergent drugresistant (G418-resistant) colonies using Giemsa. We digitized the tissue culture plates using an Epson flatbed scanner set for 600 dpi. We cropped, annotated, manipulated, and combined the digital images using Adobe Photoshop Elements (San Jose, CA).

Using the actual stained tissue culture dishes we counted drug-resistant (G418-resistant) colonies and calculated the titer of each retroviral stock in each cell lines. To calculate the relative efficiency of each retrovirus stock at inducing drug-resistant colony formation in the DU-145 cell line, the titer of each retrovirus stock in the DU-145 cell line was divided by the titer of the same retrovirus stock in the C127 cell line. These values are expressed as mean percentages calculated from at least four independent sets of infections. Analogous calculations were performed using data collected from infections of the PC-3 cell line.

To calculate inhibition of drug-resistant (G418-resistant) colony formation of DU-145 cells by infection with an experimental retrovirus stock, we divided the colony formation efficiency of the experimental retrovirus stocks in DU-145 cells by the colony formation efficiency of the LXSN-ErbB4 retrovirus stock in DU-145 cells; we subtracted these values from 100%. We performed analogous calculations for all of the experimental retrovirus stocks following infection of the PC-3 cell line. These values are reported as mean percentages calculated from at least four independent sets of infections. The standard error is also reported.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting - ErbB4 expression and phosphorylation were analyzed essentially as previously described [15, 16]. Briefly, Ψ2 cells were cultured in 100 mm dishes and were starved overnight in basal medium once the cells reached 80% confluence. Cells were lysed in an isotonic lysis buffer supplemented with a nonionic detergent. Cell debris and nuclear material were removed by centrifugation. The protein concentration of the lysates was determined using a modified Bradford assay (Pierce). ErbB4 was immunoprecipitated from 1 mg of each sample using an anti-ErbB4 rabbit polyclonal antibody (SC-283, Santa Cruz) and Protein-A sepharose beads. Immunocomplexes were washed and ErbB4 was eluted from the immunocomplexes by boiling in a reducing SDS sample buffer. The eluates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. We probed the resulting blots using the 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine mouse monoclonal antibody (Upstate) to assess ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation. We assessed ErbB4 expression by probing blots with the SC-283 anti-ErbB4 rabbit polyclonal antibody. Blots were probed with an appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Pierce) and antibody binding was visualized by ECL (Amersham).

In Vitro Kinase Assays — We lysed Ψ2 cells and isolated ErbB4 as described above. We assayed ErbB4 kinase activity using a modification of a published procedure [15]. Briefly, ErbB4 immune complexes were washed in the lysis buffer and the kinase assay buffer. The immune complexes were suspended in 25 μL of kinase buffer. We incubated each sample with Redivue 5’-adenosine[γ-32P]triphosphate (50 μCi-Amersham) for 10 minutes at 30°C. The immunocomplexes were washed and ErbB4 was eluted by boiling in a reducing SDS sample buffer. The eluates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. Radiolabeled ErbB4 was visualized by autoradiography.

Phosphopeptide Mapping — We performed 1-dimensional phosphopeptide mapping as described [22, 23]. Each section of nitrocellulose corresponding to radiolabeled ErbB4 was excised from the blot and incubated in 500 μL of 0.5% PVP-360 in 100 mM acetic acid for 30 minutes at 37°C with shaking. We washed the nitrocellulose in deionized water and 50 mM NH4HCO3. We added 300 μL of 50 mM NH4HCO3 and 10 μL of 1 mg/ml trypsin in 50 mM NH4HCO3 to each sample. We incubated the samples at 37°C for two hours then incubated the samples for two more hours with an additional 10 μL of the trypsin solution. We added deionized water to each sample and transferred the liquid to a fresh tube. Samples were vacuum dried and the radioactivity was quantified by Cerenkov counting. We dissolved the dried samples in 10 μL of sample loading buffer and resolved the samples by PAGE using an alkaline gel containing 40% acrylamide. We dried the gel and visualized the radiolabeled tryptic peptides by autoradiography.

Anchorage independence assay — We infected PC-3 cells as described above with the ErbB4 WT and LXSN retroviruses. Drug-resistant infected cells were selected and pooled. This resulted in the generation of the PC-3 ErbB4 and PC-3 LXSN stable cell lines. We added 2 mL of complete medium containing 0.3% low melting point agarose to 60 mm dishes and placed at 4°C until medium solidified. Plates were then warmed in a 37°C cell culture incubator. We then added 1 mL of complete medium containing 0.3% low melting point agarose and 2 x 104 cells to the solidified layer in each 60 mm dish. The top layer containing cells was incubated for one hour at 4°C and then transferred to a 37°C incubator containing 5% CO2. Every three days 0.75 mL of fresh medium containing 0.3% low melting point agarose was added to each plate and solidified for one hour at 4°C. After allowing cells to grow for 13 days, we photographed eight random fields from each plate using a Nikon Coolpix 4500 digital camera attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 25 microscope. The number of single cells and colonies were counted in each field. We calculated the percentage of cells that formed colonies for the PC-3 ErbB4 and PC-3 LXSN cell lines. We used a t-test to calculate significant difference between the two cell lines.

Results

ErbB4 Kinase Activity Is Essential for the Biological Activity of the ErbB4 Q646C Mutant - We have previously reported that infection of the DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate tumor cell lines with a recombinant retrovirus that expresses both wild-type ErbB4 and the neomycin resistance gene results in abundant G418-resistant (drug-resistant) colonies. In contrast, infection with a recombinant retrovirus that expresses the constitutively-active Q646C ErbB4 mutant and the neomycin resistance gene results in far fewer G418-resistant (drugresistant) colonies [16]. Control infections indicate that this difference in drug-resistant colony formation is not due to a difference in viral titers, suggesting that the ErbB4 Q646C mutant actively inhibits drug-resistant colony formation by coupling to growth arrest or apoptosis. Thus, the ErbB4 Q646C mutant appears to behave as a tumor suppressor in the DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate tumor cell lines [16].

Here we have sought to decipher the mechanism by which the Q646C mutant is coupled to this biological activity. Given that ErbB4 is a member of the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases, we hypothesized that ErbB4 tyrosine kinase activity is required for inhibition of colony formation. We tested this hypothesis by assaying the activity of ErbB4 Q646C Kin-, a mutant in the context of ErbB4 Q646C that lacks tyrosine kinase activity (K751M) [17].

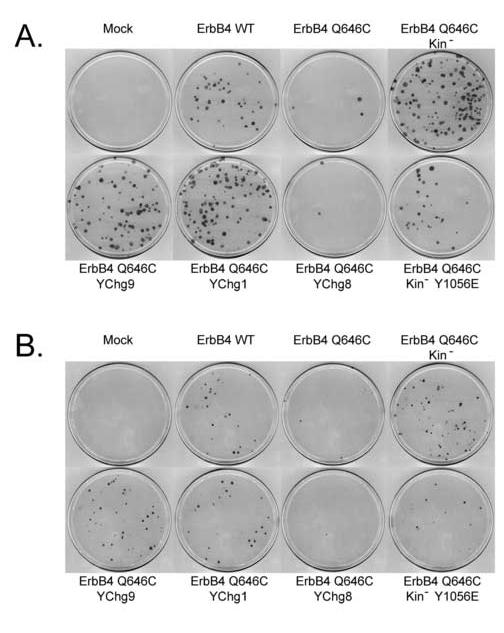

Figure 1 indicates that infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with the ErbB4 Q646C retrovirus results in fewer G418-resistant (drug-resistant) colonies than observed following infection with the wild-type ErbB4 retrovirus (ErbB4 WT). We have performed control infections of C127 cells, which do not respond to ErbB4 signaling [16], to account for the potential effects of differences in viral titer. The results of these experiments indicate that the ErbB4 Q646C retrovirus inhibits drug-resistant colony formation by DU-145 and PC-3 cells by greater than 85% relative to the wild-type ErbB4 retrovirus (Table 1), in close agreement with previously published results [16]. We have chosen to compare the activity of the ErbB4 mutants to that of wild-type ErbB4 rather than a vector control in order to account for any effects of ligand-independent signaling by wild-type ErbB4. Nonetheless, it should be noted that drugresistant colony formation following infection with the wild-type ErbB4 retrovirus is equivalent to drug-resistant colony formation following infection with the vector control ErbB4 retrovirus [16].

Fig. 1.

Tyrosine 1056 of ErbB4 Q646C is necessary and may be sufficient to inhibit colony formation by prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate cancer cell lines were infected with recombinant retroviruses that express the ErbB4 Q646C constitutively-active mutant, the kinase deficient ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant, ErbB4 Q646C YChg1, ErbB4 Q646C YChg9, ErbB4 Q646C YChg8, or ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E. Drug-resistant colonies were fixed, stained, and counted. A, DU-145; B, PC-3.

Table 1.

The ErbB4 Q646C, Q646C YChg8, and Q646C Kin- Y1056E mutants inhibit colony formation by DU-145 and PC-3 prostate tumor cell lines, but other ErbB4 mutants do not.

| Cell Line/Virus | Retrovirus Titer (CFU/mL) | Colony Formation Efficiency (% of C127) | Specific Inhibition of Colony Formation (% Relative to ErbB4 WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C127 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 2.3×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 5.4×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 | 6.4×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 | 7.6×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 | 9.4×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- | 3.9×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E | 5.4×106 | 100 | |

| DU-145 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 1.4×104 | 6.44 (N=4) | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 9.8×102 | 0.19 (N=4) | 97.5 ± 0.7 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 | 6.6×104 | 11.39 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 | 1.5×103 | 0.22(N=4) | 96.1 ± 1.0 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 | 6.2×104 | 7.71 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- | 2.7×104 | 7.43 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E | 1.4×105 | 2.75 (N=4) | 50.9 ± 11.3 (N=4) |

| PC-3 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 2.4×104 | 12.00 (N=4) | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 8.0×103 | 1.65 (N=4) | 87.0 ± 4.1 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 | 8.8×104 | 14.17 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 | 9.7×104 | 1.10(N=4) | 90.4 ± 1.5 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 | 9.0×104 | 12.48 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- | 4.9×104 | 14.58 (N=4) | None (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E | 2.8×105 | 5.59 (N=4) | 54.9 ± 3.9 (N=4) |

Infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant results in abundant G418-resistant colonies (Figure 1). Control infections to account for the potential effects of differences in viral titer indicate that the Q646C Kin- mutant fails to display any detectable inhibition of drug-resistant colony formation (Table 1). Thus, these results indicate that kinase activity is required for inhibition of colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

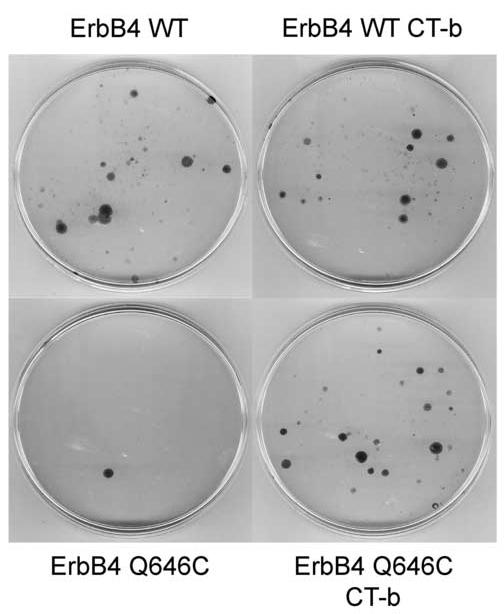

The ErbB4 CT-b Splicing Isoform Fails to Support the Biological Activity of the ErbB4 Q646C Mutant - There are multiple splicing isoforms of ErbB4. The cytoplasmic or carboxyl-terminal (CT) isoforms differ in the presence (CT-a) or absence (CT-b) of a 16 amino acid sequence that includes Ser1046 through Gly1061. The ErbB4 Q646C mutant characterized in our published work [16] and up to this point of the present study was generated in the context of the CT-a isoform [15]. Published data suggest that the ErbB4 CT-b isoform fails to couple to growth inhibition and tumor suppression [5]. Thus, we assayed the activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant in the context of the CT-b isoform. Infection of DU-145 cells with the ErbB4 Q646C CT-b mutant results in abundant drug-resistant colonies (Figure 2). Control infections indicate that this mutant fails to inhibit colony formation by the DU-145 cell line (Table 2). Likewise, the ErbB4 Q646C CT-b mutant inhibits colony formation by the PC-3 cell line to a much lesser extent than did the ErbB4 Q646C mutant (Table 2). This result suggests that some or all of the 16 amino acids absent in the CT-b isoform are essential for inhibition of colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

Fig. 2.

The ability of ErbB4 Q646C to inhibit colony formation by prostate cancer cells is isoform dependent. A prostate cancer cell line (DU-145) was infected with recombinant retroviruses that express the CT-b mutant in the context of wild type ErbB4 (ErbB4 WT CT-b) or of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant (ErbB4 Q646C CT-b). Cells were infected with the appropriate control retroviruses. Drug-resistant colonies were fixed, stained, and counted.

Table 2.

In the context of the CT-b isoform the ErbB4 Q646C mutant fails to inhibit colony formation by DU-145 and PC-3 prostate tumor cell lines.

| Cell Line/Virus | Retrovirus Titer (CFU/mL) | Colony Formation Efficiency (% of C127) | Specific Inhibition of Colony Formation (% Relative to ErbB4 WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C127 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 1.94×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 4.55×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 WT CT-b | 1.05×105 | 100 | |

| ErbB4 Q646C CT-b | 1.06×105 | 100 | |

| DU-145 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 1.4×104 | 8.58 (N=7) | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 7.7×102 | 0.25 (N=7) | 97.0 ± 1.0 (N=7) |

| ErbB4 WT CT-b | 7.6×103 | 9.06 (N=7) | None (N=7) |

| ErbB4 Q646C CT-b | 6.9×103 | 8.24 (N=7) | None (N=7) |

| PC-3 | |||

| ErbB4 WT | 6.4×104 | 52.67 (N=4) | |

| ErbB4 Q646C | 1.7×104 | 7.06 (N=4) | 89.0 ± 3.7 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 WT CT-b | 4.0×104 | 65.26 (N=4) | -11.3 ± 23.2 (N=4) |

| ErbB4 Q646C CT-b | 2.9×104 | 43.93 (N=4) | 17.1 ± 13.7 (N=4) |

ErbB4 Tyr1056 Is Critical for the Biological Activity of the ErbB4 Q646C Mutant - Since ErbB4 tyrosine kinase activity is necessary for the activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant, we speculated that ErbB4 tyrosine autophosphorylation might also be necessary for the activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. Tyrosine residues at 1022, 1056, 1150, 1162, 1188, 1202, 1242, 1258, and 1284 were identified as candidate autophosphorylation sites [9, 24]. All nine of these sites were mutated to phenylalanine to produce the ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 mutant [17]. Infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with this mutant results in abundant drug-resistant colonies (Figure 1). Control infections indicate that this mutant fails to inhibit drug-resistant colony formation by either prostate cancer cell line (Table 1). These data suggest that phosphorylation of one or more of these tyrosines is necessary for inhibition of colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

One difference between the ErbB4 CT-a and CT-b splicing isoforms is that the CT-b isoform lacks Tyr1056 [3, 9]. Because the CT-b isoform fails to support inhibition of drugresistant colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant, we speculated that Tyr1056 may be critical for this biological activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. We tested this hypothesis by changing Tyr1056 to phenylalanine in the context of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant, resulting in the ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 mutant [17]. Infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with this mutant results in abundant drug-resistant colonies (Figure 1). Control infections indicate that this mutant fails to inhibit drug-resistant colony formation by either prostate cancer cell line (Table 1), suggesting that Tyr1056 is necessary for the biological activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

Next we reintroduced Tyr1056 into the ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 mutant, resulting in the ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 mutant [17]. Infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with this mutant results in fewer drug-resistant colonies than does infection with the YChg9 mutant (Figure 1). Indeed, control infections indicate that the YChg8 mutant inhibits colony formation by both prostate cancer cell lines (Table 1). The extent of this inhibition is similar to that displayed by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant (Table 1). Thus, with respect to sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation, phosphorylation of Tyr1056 may be sufficient for the biological activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

However, these results do not rule out the possibility that additional sites of ErbB4 tyrosine autophosphorylation present in the YChg8 or YChg9 mutants may mediate the biological activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. To address this issue we substituted a phosphomimic glutamate residue for Tyr1056 in the context of the kinase-deficient ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant, generating the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E mutant. Infection of DU-145 and PC-3 cells with this mutant results in far fewer drug-resistant colonies than does infection with the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant (Figure 1). Analyses of control infections indicate that this mutant inhibits drug-resistant colony formation to a slightly lesser extent than does the ErbB4 Q646C mutant (Table 1). Nonetheless, these data suggest that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 is indeed sufficient for at least some of the biological activity of the ErbB4 Q646C mutant.

The Failure of ErbB4 Mutants to Inhibit Colony Formation Is Not Due to Reduced Expression - One potential mechanism underlying the failure of the ErbB4 Q646C Kin-, YChg1, and YChg9 mutants to inhibit colony formation is that these mutants may not be stably expressed. We have addressed this possibility by evaluating the expression of these mutants. Ideally we would demonstrate that the ErbB4 mutants that fail to inhibit colony formation are stably expressed at equal or higher levels in DU-145 and PC-3 cells than those that do inhibit colony formation. This would suggest that the reduced biological activity of these mutants is not due to inadequate expression. Unfortunately, efforts to detect the expression of the ErbB4 mutants in stably infected DU-145 and PC-3 cells have failed (unpublished data). In the case of the ErbB4 Q646C, Q646C YChg8, and Q646C Kin- Y1056E mutants this may be due to the fact that the growth inhibitory effects of these mutants are quite potent and may preclude high levels of stable expression. However, even the mutants that do not inhibit colony formation are not expressed at detectable levels in stably infected DU-145 and PC-3 cell lines. Thus a comparison of expression in these cells is not possible.

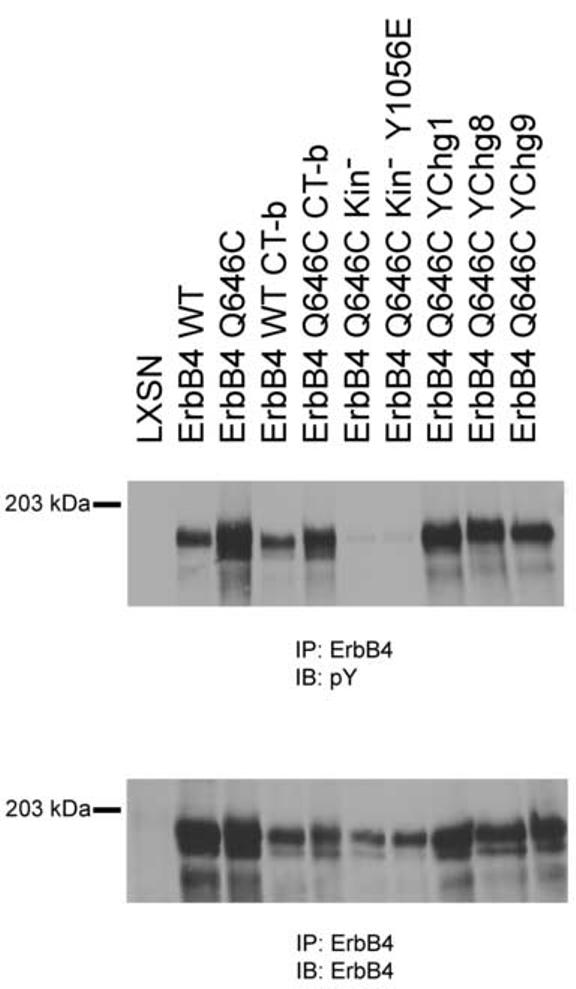

Thus, we have evaluated the expression of the ErbB4 mutants using Ψ2 ecotropic retrovirus packaging cells stably transfected with the various ErbB4 constructs. The ErbB4 Q646C CT-b, YChg1 and YChg9 mutants display varying amounts of expression (Figure 3, lower panel). However, all three of these loss-of-function mutants are expressed to a greater extent than the ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 mutant. Because the YChg8 mutant effectively inhibits colony formation by the DU-145 and PC-3 cell lines, the failure of the CT-b, YChg1, and YChg9 mutants to inhibit colony formation does not appear to be due to reduced expression. In contrast, the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant is expressed at a lower level than is the ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 mutant (Figure 3, lower panel). Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that the reduced expression of the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant is responsible for the reduced biological activity of this mutant. The level of expression of the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant is similar to that displayed by the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E. Although the latter mutant does inhibit colony formation, it is not nearly as effective as the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. Thus, the failure of the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- and ErbB4 Q646C Kin- Y1056E mutants to fully inhibit colony formation could be due to reduced expression.

Fig. 3.

ErbB4 mutants are expressed and appropriately tyrosine phosphorylated in Ψ2 cells. ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation (upper panel) and expression (lower panel) in engineered Ψ2 cells were analyzed as described elsewhere.

As expected, the ErbB4 Q646C, Q646C CT-b, and Q646C YChg1 mutants all display abundant tyrosine phosphorylation (Figure 3, upper panel). Surprisingly, wild-type ErbB4 and the ErbB4 WT CT-b mutants display ligand-independent tyrosine phosphorylation. Apparently the high levels of ErbB4 expression observed in the transfected Ψ2 cell lines is sufficient for stochastic ErbB4 dimerization and ligand-independent signaling. We were also surprised to note that the YChg8 and YChg9 mutants display significant tyrosine phosphorylation. Either there are additional bona fide sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation or mutating the bona fide sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation permits ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation at cryptic sites.

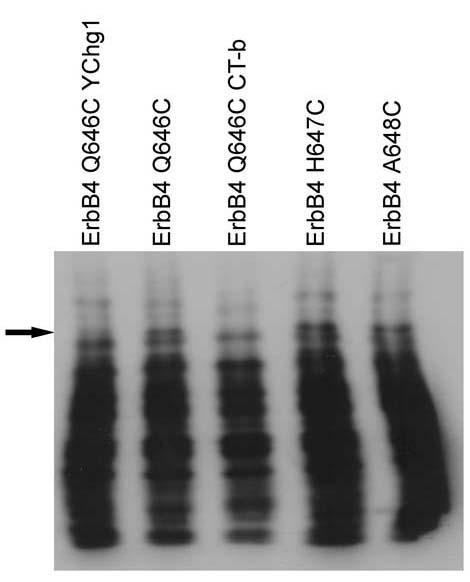

ErbB4 Phosphorylation at Tyr1056 Correlates With the Biological Activity of the ErbB4 Mutants — The mutational analyses of the putative sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation suggest that ErbB4 phosphorylation at Tyr1056 is critical for inhibition of colony formation by the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. However, these analyses do not rule out the possibility that Tyr1056 plays a critical role independent of its phosphorylation. We have addressed this issue by mapping sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation.

We performed in vitro kinase assays using ErbB4 immunoprecipitates and radiolabeled ATP. Radiolabeled phospho-ErbB4 was resolved by SDS-PAGE, isolated, and digested with trypsin. The tryptic fragments were resolved using an alkaline acrylamide gel. The arrow in Figure 4 indicates an ErbB4 tryptic phosphopeptide that is present in the ErbB4 Q646C mutant and absent in the ErbB4 Q646C YChg1 and ErbB4 Q646C CT-b mutants. An ErbB4 tryptic phosphopeptide with identical mobility is present in the ErbB4 Q646C YChg8 mutant and absent in the ErbB4 Q646C YChg9 mutant (data not shown). Comparison of the ErbB4 phosphopeptide maps with the predicted sequence of the ErbB4 tryptic phosphopeptides suggests that this phosphopeptide is SEIGHSPPPApYTPMSGNQFVYR, in which the phosphorylated tyrosine residue is Tyr1056. Thus, these data indicate that Tyr1056 is indeed a bona fide site of in vitro ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation.

Fig. 4.

Tyrosine 1056 appears to be a bona fide site of in vitro phosphorylation in the ErbB4 Q646C mutant. Sites of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation were mapped using in vitro kinase assays, tryptic peptide digestion, and 1-dimensional gel electrophoresis as described elsewhere. Shown is a representative autoradiogram comparing the patterns of tyrosine phosphorylation for ErbB4 Q646C, ErbB4 Q646C YChg1, ErbB4 Q646C CT-b, ErbB4 H647C, and ErbB4 A648C. The arrow indicates the band corresponding to the phosphopeptide that includes phospho-Tyrosine 1056.

It could be argued that Tyr1056 is not the actual or only site of in vitro phosphorylation within the tryptic phosphopeptide SEIGHSPPPAYTPMSGNQFVYR. Indeed, this tryptic phosphopeptide contains several serine and threonine residues as well as an additional tyrosine residue (Tyr1066). However, Tyr1066 is not a putative site of phosphorylation [9, 24]. Furthermore, given that the phosphorylation of this peptide is expected to be catalyzed by the ErbB4 tyrosine kinase domain, it seems implausible to predict that this peptide is phosphorylated on a serine or threonine residue. (Indeed, unpublished data indicate that in vitro kinase assays performed using the ErbB4 Q646C Kin- mutant fail to yield detectable ErbB4 phosphorylation.) Finally, the absence of phosphorylation of this tryptic peptide in the Q646C YChg1 and YChg8 mutants would suggest that the phosphorylation of residues other than Tyr1056 within the tryptic peptide must be dependent upon phosphorylation at Tyr1056. Thus, the most plausible explanation is that Tyr1056 is a bona fide site of in vitro phosphorylation and that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 is critical for the biological activity of the ErbB4 mutant.

We have extended these findings by comparing the pattern of ErbB4 tyrosine phosphorylation displayed by the Q646C, H647C, and A648C mutants. Despite the fact that all three of these mutants display ligand-independent tyrosine phosphorylation [15], only the Q646C mutant inhibits colony formation by the DU-145 and PC-3 cell lines [16]. Surprisingly, like the ErbB4 Q646C mutant, the H647C and A648C mutants are phosphorylated on Tyr1056 (Figure 4). Apparently the H647C and A648C mutants lack some other activity necessary for coupling ErbB4 to inhibition of colony formation.

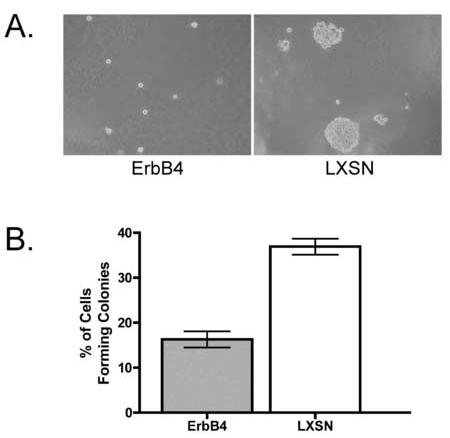

ErbB4 inhibits anchorage independent growth of PC-3 cells — To confirm that the ErbB4 Q646C mutant does indeed model signaling by wild-type ErbB4, we evaluated whether signaling by wild-type ErbB4 modulates the behavior of PC-3 cells. We infected PC-3 cells with a vector control (LXSN) retrovirus or a retrovirus that directs expression of wild-type ErbB4 (ErbB4) and selected for infected cells using G418. We pooled drug-resistant cells to generate the PC-3 LXSN and PC-3 ErbB4 stable cell lines. We seeded these infected cell lines in a semisolid medium and assayed anchorage independent proliferation. After incubation for thirteen days, eight random fields representing each cell line were photographed. We counted the number of cells that formed colonies or remained as single cells. Representative photomicrographs and the quantification of results obtained from three independent experiments are shown in Figure 5. These results clearly show that wild-type ErbB4 significantly inhibited the anchorage- independent proliferation of PC-3 cells by approximately 50%. These results suggest that wild-type ErbB4 inhibits the proliferation of prostate cancer cells and that our ErbB4 Q646C mutant is an appropriate model for signaling by wild-type ErbB4.

Fig. 5.

ErbB4 inhibits PC-3 anchorage independent growth. PC-3 ErbB4 and PC-3 LXSN cells were seeded in semisolid medium and incubated for 13 days. A, Representative photomicrographs of these cells are shown. B, Average percentage of cells that formed colonies in the two cell lines ± SEM. n = 3; P < 0.005.

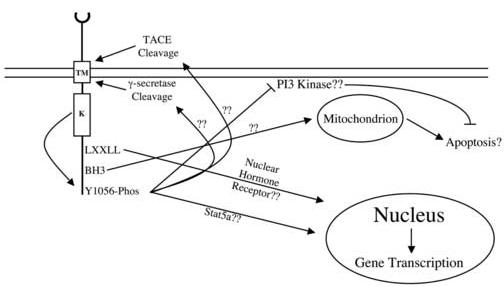

Discussion

Phosphorylation of ErbB4 Tyrosine 1056 is Critical for the Biological Activity of the Q646C Mutant - Here we demonstrate that phosphorylation of ErbB4 Tyr1056 is necessary for the ErbB4 Q646C mutant to inhibit formation of colonies on plastic by prostate cancer cell lines. We propose that although the H647C and A648C mutants contain pTyr1056 they lack the ability to couple to the required signaling events that are necessary for inhibition of colony formation. We hypothesize that the structure of the ErbB4 dimers determines whether Tyr1056 is accessible to a critical signaling effector. The H647C and A648C dimers could sterically block an effector from binding to pTyr1056. It is also possible that the conformation of the H647C and A648C dimers prevents proper processing of the receptors. As discussed later, cleavage of ErbB4 and release from the membrane may be necessary for biological function. The H647C and A648C dimers may not permit proper cleavage. Studies are underway to address these two possibilities.

Mechanisms of ErbB4 Tumor Suppression - There are several potential mechanisms by which phosphorylation of Tyr1056 could couple to inhibition of colony formation by prostate cancer cell lines. One mechanism is that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 couples to a signaling pathway that results in the growth arrest or apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Tyr1056 resides in a region that contains a PI3K SH2 binding motif as well as a WW binding motif. ErbB4 may be coupled to prostate tumor suppression through stimulation or inhibition of signaling through one of these pathways. It is possible that ErbB4 could activate PI3K through its binding to the phosphorylated receptor. Traditionally it has been thought that PI3K is a pro-survival protein and that PI3K signaling prevents apoptosis. However, a recent report suggests that the exact cellular response to PI3K activation may be isoform dependent and cell type specific [25]. Moreover, reports indicate that Neuregulin stimulation of growth arrest requires PI3K activity [26, 27]. Alternatively, phosphorylation of Tyr1056 may recruit PI3K but may instead sequester or otherwise inactivate PI3K, thereby preventing PI3K signaling and resulting in apoptosis. Experiments are underway to probe the roles that PI3K may play in coupling the ErbB4 Q646C mutant to inhibition of colony formation.

Phosphorylation of Tyr1056 may also regulate the binding of proteins through the WW domain binding motif. ErbB4 contains three WW domain binding motifs, including one that contains Tyr1056. ErbB4 binds the WW domain of the transcriptional co-activator YAP proteins [7, 8]. It is possible that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 determines the stoichiometry of the ErbB4-YAP complex, localization of the complex, association with other transcriptional control proteins, or activity.

Another potential mechanism is that phosphorylation of Tyr1056 regulates localization and trafficking of ErbB4. Phosphorylation of Tyr1056 may result in the cleavage of ErbB4 and subsequent release of the cytoplasmic domain from the plasma membrane. This would allow the translocation of the cytoplasmic domain to different intracellular regions, whereupon the cytoplasmic domain could induce growth arrest or apoptosis. Indeed, following ligand stimulation the ErbB4 cytoplasmic domain is cleaved, associates with STAT5, translocates to the nucleus, and modulates gene expression [6]. This binding to STAT5 and translocation to the nucleus may result in the transcription of genes that cause cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. The hypothesis that translocation of the ErbB4 cytoplasmic domain to the nucleus is critical for ErbB4 function is supported by the fact that the ErbB4 cytoplasmic domain contains two nuclear hormone receptor binding motifs (LXXLL). The ErbB4 cytoplasmic domain also contains a BH3 motif, which has been hypothesized to mediate interactions between ErbB4 and apoptotic proteins. Indeed, the BH3 motif regulates the biological activity of ErbB4 in breast cancer cells [28, 29]. Thus, the ErbB4 cytoplasmic domain may translocate to mitochondria and interact with proteins that modulate apoptosis [28, 29]. By coupling to ErbB4 cleavage, the phosphorylation of ErbB4 Tyr1056 may be critical for ErbB4 coupling to growth arrest or apoptosis. Experiments to evaluate this hypothesis are underway.

Fig. 6.

Possible mechanisms of ErbB4 signaling. TM, transmembrane domain; K, kinase domain.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from NIH (R21CA080770 and R21CA089274 to D.J.R.), the US Army Medical Research and Material Command (DAMD17-00-1-0145, DAMD17-00-1-0416, and DAMD17-02-0130 to D.J.R.), the Indiana Elks Foundation (to D.J.R.), the American Cancer Society (IRG-58-006 to the Purdue Cancer Research Center), a Purdue University Andrews Fellowship (to R.M.G.) and a Purdue University Graduate School Summer Research Grant (to R.M.G.).

Footnotes

- BH3

- Bcl-2 homology 3

- CFU

- colony forming units

- CT

- carboxy-terminal

- ECL

- enhanced chemiluminescence

- EGFR

- Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- JM

- juxtamembrane

- Kin-

- kinase deficient

- PTB

- phosphotyrosine binding

- PVP-360

- polyvinylpyrrolidone, Mr 360,000

- SH2

- src-homology 2

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TACE

- tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme

- TBST

- Tris buffered saline with Tween-20

- WT

- wild type

- YAP

- Yes associated protein

- YChg#

- the number of tyrosines that have been mutated to phenylalanine

References

- [1].Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. The EGF family of growth factors. J Clin Ligand Assay. 2000;23:233–238. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Carpenter G. ErbB-4: mechanism of action and biology. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:66–77. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ni CY, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Carpenter G. gamma -Secretase cleavage and nuclear localization of ErbB-4 receptor tyrosine kinase. Science. 2001;294:2179–2181. doi: 10.1126/science.1065412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Junttila TT, Sundvall M, Lundin M, Lundin J, Tanner M, Harkonen P, Joensuu H, Isola J, Elenius K. Cleavable ErbB4 isoform in estrogen receptor-regulated growth of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1384–1393. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Williams CC, Allison JG, Vidal GA, Burow ME, Beckman BS, Marrero L, Jones FE. The ERBB4/HER4 receptor tyrosine kinase regulates gene expression by functioning as a STAT5A nuclear chaperone. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:469–478. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Omerovic J, Puggioni EM, Napoletano S, Visco V, Fraioli R, Frati L, Gulino A, Alimandi M. Ligand-regulated association of ErbB-4 to the transcriptional co-activator YAP65 controls transcription at the nuclear level. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Komuro A, Nagai M, Navin NE, Sudol M. WW domain-containing protein YAP associates with ErbB-4 and acts as a co-transcriptional activator for the carboxyl-terminal fragment of ErbB-4 that translocates to the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33334–33341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kainulainen V, Sundvall M, Maatta JA, Santiestevan E, Klagsbrun M, Elenius K. A natural ErbB4 isoform that does not activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase mediates proliferation but not survival or chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8641–8649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Salomon DS, Brandt R, Ciardiello F, Normanno N. Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in human malignancies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1995;19:183–232. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)00144-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robinson D, He F, Pretlow T, Kung HJ. A tyrosine kinase profile of prostate carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5958–5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Grasso AW, Wen D, Miller CM, Rhim JS, Pretlow TG, Kung HJ. ErbB kinases and NDF signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 1997;15:2705–2716. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lyne JC, Melhem MF, Finley GG, Wen D, Liu N, Deng DH, Salup R. Tissue expression of neu differentiation factor/heregulin and its receptor complex in prostate cancer and its biologic effects on prostate cancer cells in vitro. Cancer J Sci Am. 1997;3:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Memon AA, Sorensen BS, Melgard P, Fokdal L, Thykjaer T, Nexo E. Expression of HER3, HER4 and their ligand heregulin-4 is associated with better survival in bladder cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:2034–2041. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Penington DJ, Bryant I, Riese DJ., 2nd Constitutively active ErbB4 and ErbB2 mutants exhibit distinct biological activities. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13:247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Williams EE, Trout LJ, Gallo RM, Pitfield SE, Bryant I, Penington DJ, Riese DJ. A constitutively active ErbB4 mutant inhibits drug-resistant colony formation by the DU-145 and PC-3 human prostate tumor cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2003;192:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pitfield SE, Bryant I, Penington DJ, Park G, Riese DJ., 2nd Phosphorylation of ErbB4 on tyrosine 1056 is critical for ErbB4 coupling to inhibition of colony formation by human mammary cell lines. Oncol Res. 2006 doi: 10.3727/000000006783981134. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vidal GA, Clark DE, Marrero L, Jones FE. A constitutively active ERBB4/HER4 allele with enhanced transcriptional coactivation and cell-killing activities. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Riese DJ, 2nd, DiMaio D. An intact PDGF signaling pathway is required for efficient growth transformation of mouse C127 cells by the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Oncogene. 1995;10:1431–1439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leptak C, Ramon y Cajal S, Kulke R, Horwitz BH, Riese DJ, 2nd, Dotto GP, DiMaio D. Tumorigenic transformation of murine keratinocytes by the E5 genes of bovine papillomavirus type 1 and human papillomavirus type 16. J Virol. 1991;65:7078–7083. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.7078-7083.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Riese DJ, 2nd, van Raaij TM, Plowman GD, Andrews GC, Stern DF. The cellular response to neuregulins is governed by complex interactions of the erbB receptor family. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5770–5776. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Keshvara LM, Isaacson CC, Yankee TM, Sarac R, Harrison ML, Geahlen RL. Syk- and Lyn-dependent phosphorylation of Syk on multiple tyrosines following B cell activation includes a site that negatively regulates signaling. J Immunol. 1998;161:5276–5283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].West MHP, Wu RS, Bonner WM. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of small peptides. Electrophoresis. 1984;5:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Carraway KL, 3rd, Cantley LC. A neu acquaintance for erbB3 and erbB4: a role for receptor heterodimerization in growth signaling. Cell. 1994;78:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Luo J, Sobkiw CL, Logsdon NM, Watt JM, Signoretti S, O’Connell F, Shin E, Shim Y, Pao L, Neel BG, Depinho RA, Loda M, Cantley LC. Modulation of epithelial neoplasia and lymphoid hyperplasia in PTEN+/-mice by the p85 regulatory subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10238–10243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504378102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hamburger AW, Yoo JY. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates heregulin-induced growth inhibition in human epithelial cells. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:2197–2200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Puricelli L, Proiettii CJ, Labriola L, Salatino M, Balana ME, Aguirre Ghiso J, Lupu R, Pignataro OP, Charreau EH, Bal de Kier Joffe E, Elizalde PV. Heregulin inhibits proliferation via ERKs and phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase activation but regulates urokinase plasminogen activator independently of these pathways in metastatic mammary tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2002;100:642–653. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vidal GA, Naresh A, Marrero L, Jones FE. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase processing regulates multiple ERBB4/HER4 activities. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19777–19783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Naresh A, Long W, Vidal GA, Wimley WC, Marrero L, Sartor CI, Tovey S, Cooke TG, Bartlett JM, Jones FE. The ERBB4/HER4 intracellular domain 4ICD is a BH3-only protein promoting apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6412–6420. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]