Abstract

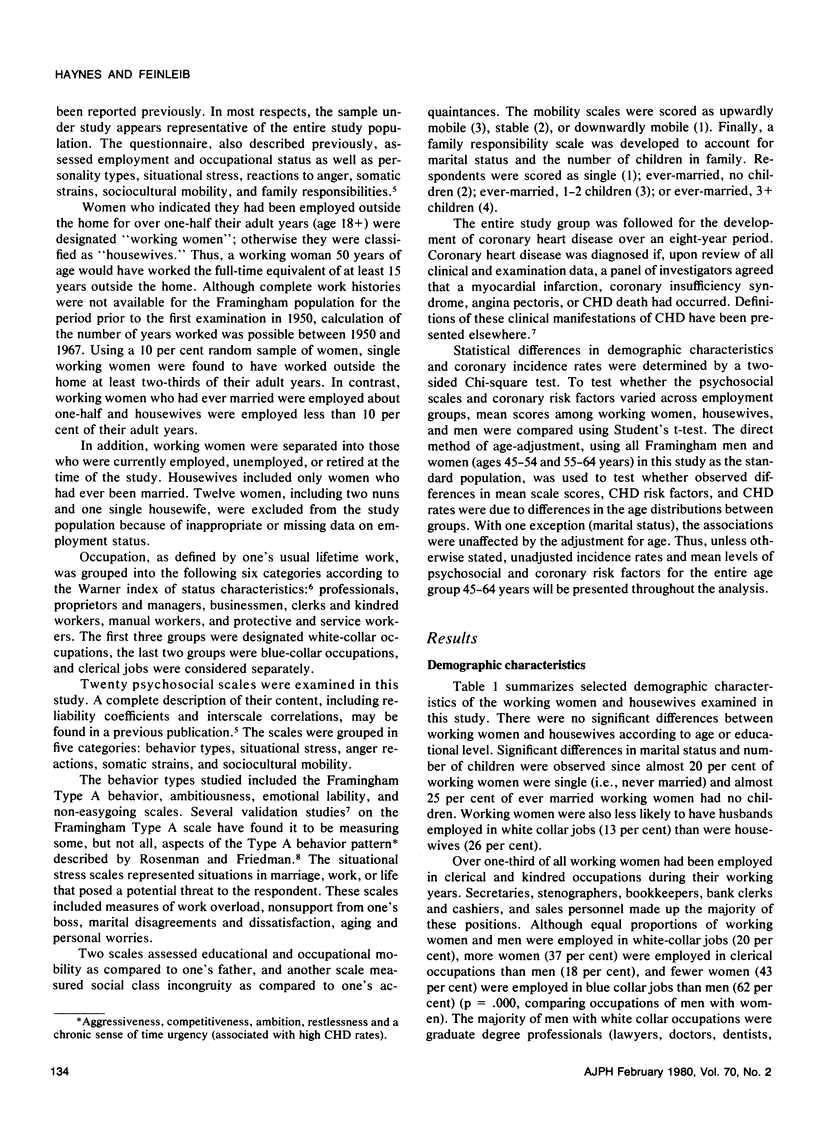

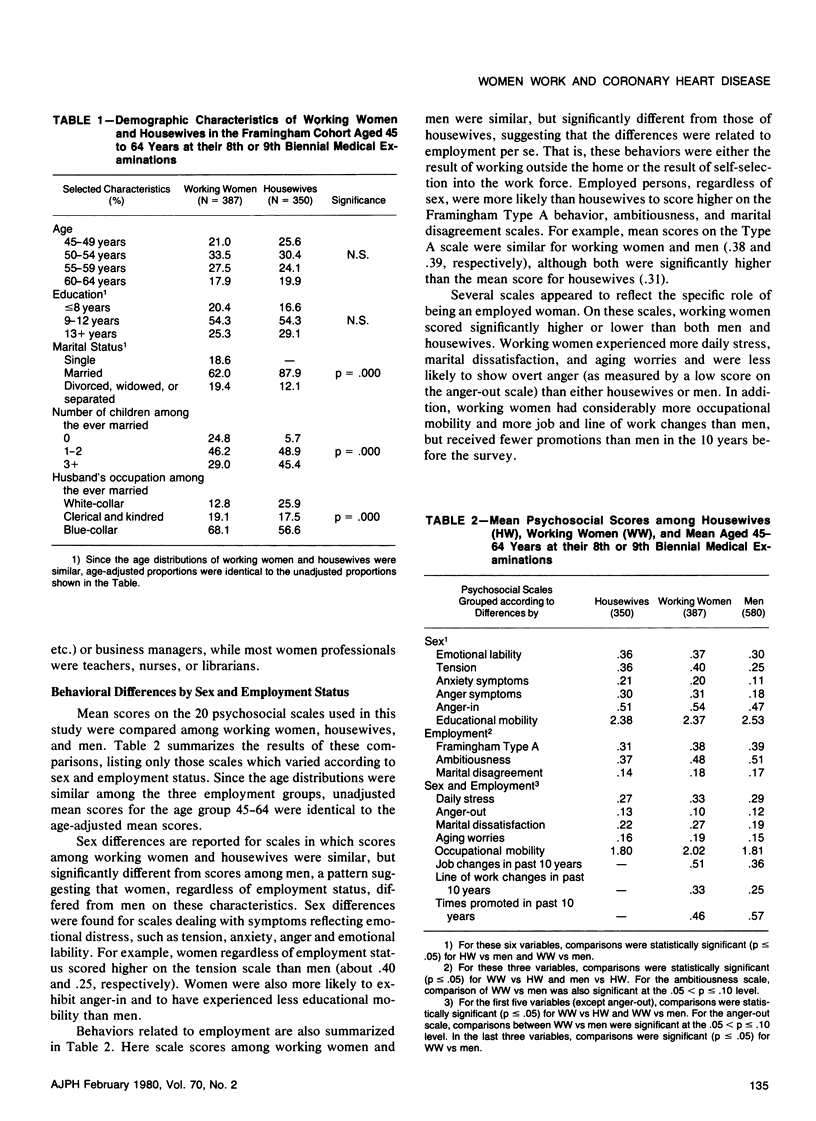

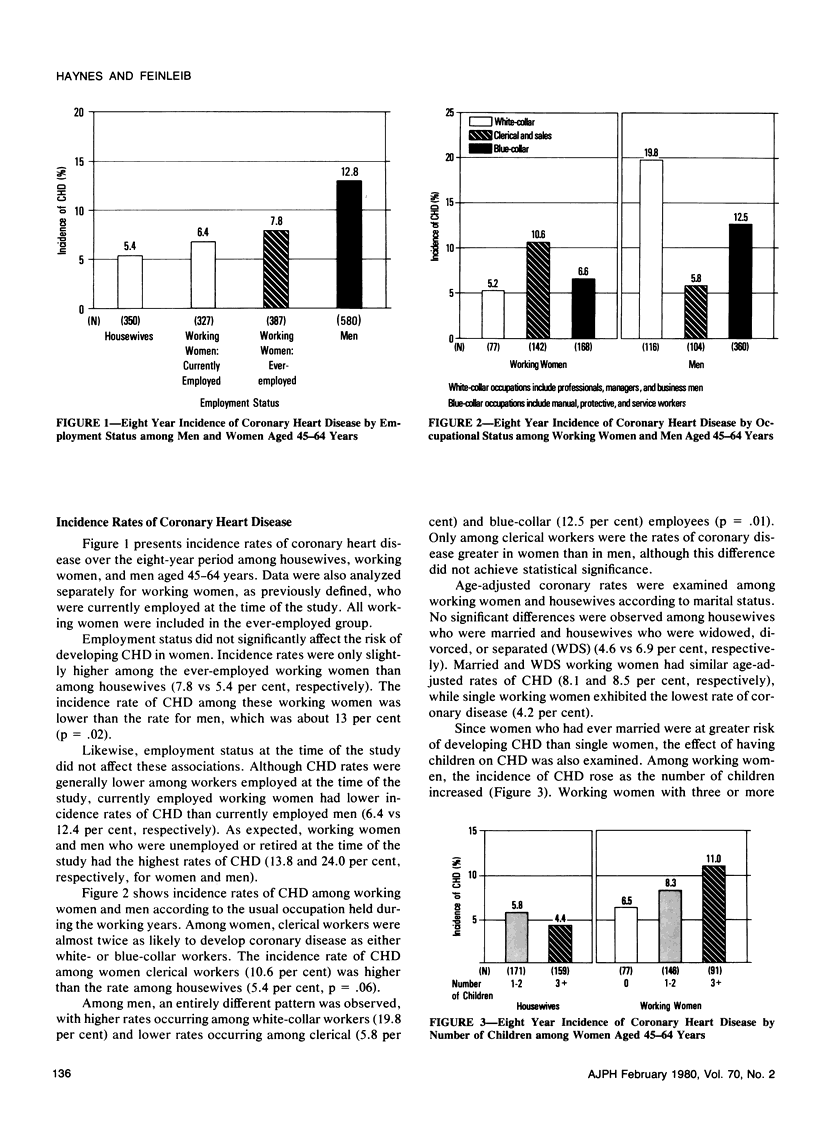

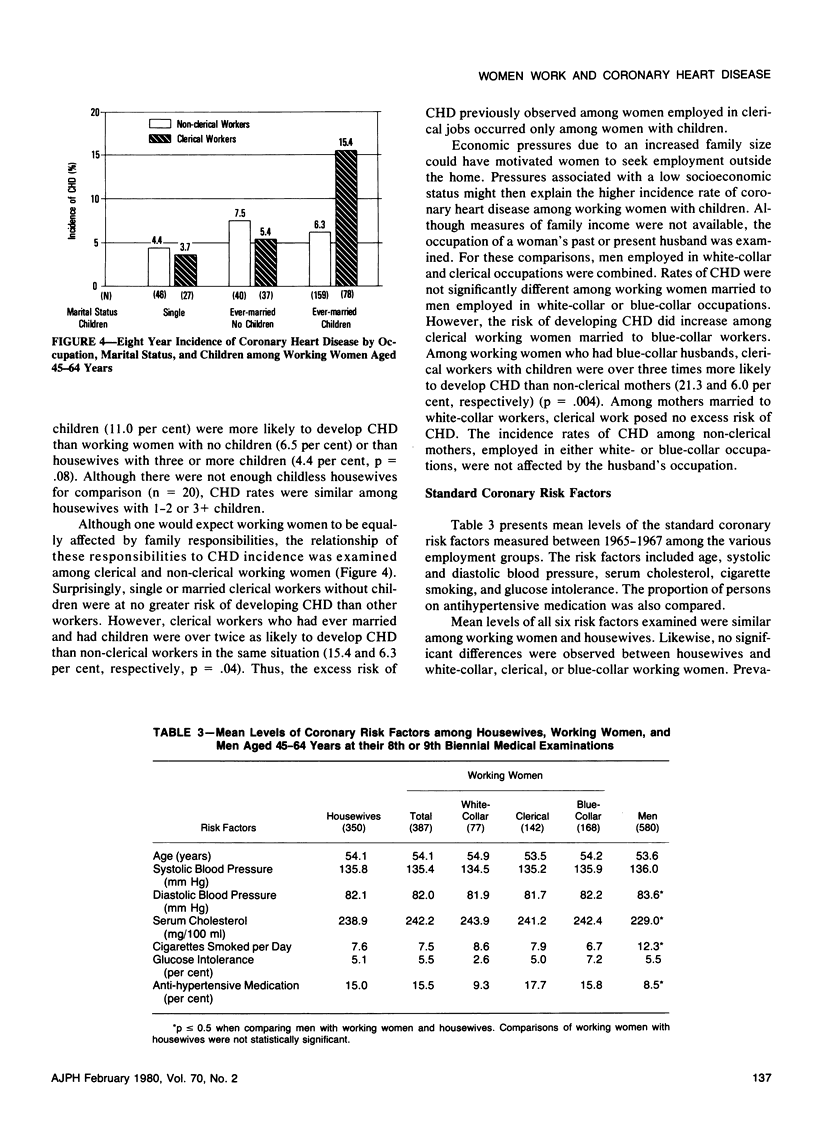

This study examined the relationship of employment status and employment-related behaviors to the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) in women. Between 1965 and 1967, a psychosocial questionnaire was administered to 350 housewives, 387 working women (women who had been employed outside the home over one-half their adult years), and 580 men participating in the Framingham Heart Study. The respondents were 45 to 64 years of age and were followed for the development of CHD over the ensuing eight years. Regardless of employment status, women reported significantly more symptoms of emotional distress than men. Working women and men were more likely to report Type A behavior, ambitiousness, and marital disagreements than were housewives; working women experienced more job mobility than men, and more daily stress and marital dissatisfaction than housewives or men. Working women did not have significantly higher incidence rates of CHD than housewives (7.8 vs 5.4 per cent, respectively). However, CHD rates were almost twice as great among women holding clerical jobs (10.6 per cent) as compared to housewives. The most significant predictors of CHD among clerical workers were: suppressed hostility, having a nonsupportive boss, and decreased job mobility. CHD rates were higher among working women who had ever married, especially among those who had raised three or more children. Among working women, clerical workers who had children and were married to blue collar workers were a highest risk of developing CHD (21.3 per cent).

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baruch R. The achievement motive in women: implications for career development. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967 Mar;5(3):260–267. doi: 10.1037/h0024300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harburg E., Blakelock E. H., Jr, Roeper P. R. Resentful and reflective coping with arbitrary authority and blood pressure: Detroit. Psychosom Med. 1979 May;41(3):189–202. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S. G., Feinleib M., Levine S., Scotch N., Kannel W. B. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. II. Prevalence of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 May;107(5):384–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes S. G., Levine S., Scotch N., Feinleib M., Kannel W. B. The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham study. I. Methods and risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 May;107(5):362–383. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. Sex differentials in coronary heart disease: the explanatory role of primary risk factors. J Health Soc Behav. 1978 Mar;18(1):46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B., Chait A., Wootton I. D., Oakley C. M., Krikler D. M., Sigurdsson G., February A., Maurer B., Birkhead J. Frequency of risk factors for ischaemic heart-disease in a healthy British population. With particular reference to serum-lipoprotein levels. Lancet. 1974 Feb 2;1(7849):141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushinski M. H., Stellman S. D. Impact of new smoking trends on women's occupational health. Prev Med. 1978 Sep;7(3):349–365. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(78)90280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENMAN R. H., FRIEDMAN M., STRAUS R., WURM M., KOSITCHEK R., HAHN W., WERTHESSEN N. T. A PREDICTIVE STUDY OF CORONARY HEART DISEASE. JAMA. 1964 Jul 6;189:15–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03070010021004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack J., Noble N., Meade T. W., North W. R. Lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in 1604 men and women in working populations in north-west London. Br Med J. 1977 Aug 6;2(6083):353–357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6083.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellman J. M. Occupational health hazards of women: an overview. Prev Med. 1978 Sep;7(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(78)90274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling T. D., Weinkam J. J. Smoking characteristics by type of employment. J Occup Med. 1976 Nov;18(11):743–754. doi: 10.1097/00043764-197611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I. The coronary-prone behavior pattern, blood pressure, employment and socio-economic status in women. J Psychosom Res. 1978;22(2):79–87. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(78)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I., Zyzanski S., Shekelle R. B., Jenkins C. D., Tannebaum S. The coronary-prone behavior pattern in employed men and women. J Human Stress. 1977 Dec;3(4):2–18. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1977.9936816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S. H., Duncan D. B. Estimation of the probability of an event as a function of several independent variables. Biometrika. 1967 Jun;54(1):167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZALOKAR J. B. Marital status and major causes of death in women. J Chronic Dis. 1960 Jan;11:50–60. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(60)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]