Abstract

Measles virus infects thymic epithelia, induces a transient lymphopenia, and impairs cell-mediated immunity, but thymic function during measles has not been well characterized. Thirty Zambian children hospitalized with measles were studied at entry, hospital discharge, and at 1-month follow-up and compared to 17 healthy children. During hospitalization, percentages of naïve (CD62L+, CD45RA+) CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes decreased (P = 0.01 for both), and activated (HLA-DR+, CD25+, or CD69+) CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes increased (P = 0.02 and 0.03, respectively). T-cell receptor rearrangement excision circles (TRECs) in measles patients were increased in CD8+ T cells at entry compared to levels at hospital discharge (P = 0.02) and follow-up (P = 0.04). In CD4+ T cells, the increase in TRECS occurred later but was more sustained. At discharge, TRECs in CD4+ T cells (P = 0.05) and circulating levels of interleukin-7 (P = 0.007) were increased compared to control values and remained elevated for 1 month, similar to observations in two measles virus-infected rhesus monkeys. These findings suggest that a decrease in thymic output is not the cause of the lymphopenia and depressed cellular immunity associated with measles.

Maintenance of T-lymphocyte populations in the peripheral circulation and in lymphoid tissues is tightly regulated by multiple homeostatic mechanisms. In healthy adults, the relative numbers of naïve and memory T lymphocytes are maintained through production of naïve T lymphocytes by the thymus and by signals promoting the survival of naïve and memory T lymphocytes in the peripheral circulation (6, 11, 22, 35, 38). This homeostasis is perturbed during an acute viral infection by the induction of a primary immune response, immune-mediated clearance of virus from infected tissues, and establishment of immunologic memory. Naïve T lymphocytes leave the circulation, and those with antigen-specific T-cell receptors (TCRs) are activated in secondary lymphoid tissue, proliferate, and differentiate into CD4+ and CD8+ effector T lymphocytes. These activated effector cells reenter the circulation and home to infected tissues, where they are active in viral clearance. Following a reduction in viral antigen, T-lymphocyte homeostasis is restored as the majority of activated, antigen-specific T lymphocytes are deleted. A small percentage of previously activated T lymphocytes persist as antigen-specific memory cells (17).

The contribution of thymic output to T-lymphocyte homeostasis can be measured by quantifying TCR rearrangement excision circles (TRECs) (14). The TREC is formed during rearrangement of V, D, and J genes to produce a functional TCR and persists as a stable, nonreplicating fragment of circular DNA. Only a single daughter cell receives a TREC during proliferation of each recent thymic emigrant. In TCR-αβ T cells, rearrangement of the TCR-A locus requires the initial deletion of the TCR-D locus (13). Because this locus is identical in the majority of αβ T cells, amplification of this region by PCR can be achieved using a single primer set (41).

Changes in thymic output during viral infection have been studied most extensively in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). TREC levels decrease with disease progression (9, 18, 48), suggesting that CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion is in part due to a reduction in thymic output. Conversely, clinical response to antiretroviral therapy is associated with an increase in TREC number (9, 14, 48). Chronic infection with HTLV-1 also is associated with a decrease in TREC numbers, perhaps contributing to the accompanying immune dysfunction (46).

Thymic output has not been well characterized during acute viral infection. Measles is an acute viral infection that is marked by changes in lymphocyte number and function. Transient lymphopenia occurs at the time of viremia, likely reflecting the accumulation of circulating naïve T lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid tissue. In addition to quantitative changes in circulating lymphocytes, measles is also accompanied by a period of immune suppression that persists for weeks to months after recovery. This state of immune suppression is characterized by depressed cellular immune responses in vivo (30, 34, 36, 43), decreased lymphoproliferative responses in vitro (3, 19, 42), and increased susceptibility to secondary infections (2).

Multiple mechanisms likely contribute to the immune suppression following measles, including alterations in thymic function. Measles virus infects epithelial cells and monocytes in the thymus (25, 45), leading to a decrease in the size of the thymic cortex (10, 44). Measles virus replication in human thymic epithelial cells in vitro results in terminal differentiation and apoptosis (39). In human thymic implants in SCID mice, measles virus infection of epithelial cells causes apoptosis of thymocytes (4). These observations support the hypothesis that impaired thymic function may contribute to measles virus-induced immune suppression. To better understand alterations in thymic function during acute measles, we measured the percentages of circulating memory, naïve, and activated T lymphocytes, the TREC content of T-lymphocyte subsets, and plasma levels of interleukin-7 (IL-7) in Zambian children during acute and convalescent measles. These results were supplemented with similar studies in experimentally infected rhesus macaques.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Children hospitalized with the clinical diagnosis of measles at the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia, between January 2000 and August 2000 were prospectively enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the children studied. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. A blood specimen was collected at study entry (usually the day following hospital admission), at hospital discharge, and at 1 month following discharge. Measles virus infection was confirmed by detection of measles virus-specific immunoglobulin M in plasma by enzyme immunoassay (Wampole Laboratories). Children coinfected with HIV, as determined by detection of HIV type 1 RNA in plasma (Amplicor version 1.5; Roche Molecular Systems), were not included in the analysis. Control children without acute illness, and without laboratory evidence of measles or HIV infection, were enrolled at a well-child clinic in Lusaka.

Animals.

Two measles virus-seronegative rhesus macaques, 1 to 2 years of age, from the Johns Hopkins University primate facility were challenged intratracheally with 104 50% tissue culture infective doses of the Bilthoven strain of measles virus (5). Blood specimens were collected prior to infection and on days 4, 7, 9, 11, 24, 28, 49, and 70 after infection. The monkeys were chemically restrained with ketamine (10 to 15 mg/kg of body weight) for all procedures. All animal experimentation was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with guidelines of the Johns Hopkins University.

Specimen processing.

Blood specimens were collected in EDTA tubes and transported to the laboratory. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were separated from whole blood on Ficoll Hypaque (Amersham) density gradients. At least 2 × 106 cells were reacted with microbead-labeled antibody against CD4, washed, resuspended, and passed over a magnetic column. The column was removed from the magnet and washed three times with 1× phosphate-buffered saline to remove the labeled cells (CD4+ T lymphocytes). Cells in the runoff from the first pass were then incubated with microbead-labeled antibody to CD8, and CD8+ cells were eluted as described for CD4+ cells. Cell populations were greater than 90% pure by flow cytometry after separation. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, pelleted, and frozen at −70°C.

Flow cytometry.

After red blood cell lysis, whole blood was stained with directly labeled monoclonal antibodies to CD3-FITC (SK7), CD4-PerCP (SK3), CD8-PerCP (SK1), CD45RA-FITC (L48), CD45RO-PE (UCHL-1), CD62L-PE (Leu-8), HLA-DR-FITC (L234), CD25-FITC (2A3), and CD69-FITC (L78) (Becton Dickinson) in humans, and CD3 (SP34, Pharmingen), CD4 (SK3; Becton Dickinson), CD8 (IOT8a; Immunotech), and CD45Ra (L48; Becton Dickinson) in rhesus macaques. Antibodies to HLA-DR, CD25, and CD69 were used as a unicolor monoclonal mix. Staining was compared to the appropriately labeled isotype control. Three-color flow cytometry was performed on a FACScan or FACScalibur flow cytometer with use of CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Quantitation of TRECs.

TRECs were quantified by real-time PCR, using the 5′ nuclease (TaqMan) assay (23) and the ABI Prism 5700 sequence detector system (PE Biosystems). Separated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from patients were lysed with 50 μl of a 100-μg/ml proteinase K solution and incubated at 56°C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by heating for 15 min at 95°C. Five microliters of cell lysate was added to each 50-μl PCR mixture containing 2.5 μl of buffer, 1.75 μl of 50 mM Mg2+, 0.5 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μl of 12.5 μM primers (5′-CACATCCCTTTCAACCATGCT-3′ and 5′-GCCAGCTGCAGGGTTTAGG-3′), 1 μl of 5 μM TaqMan probe (5′-FAM-ACACCTCTGGTTTTTGTAAAGGTGCCCACT-TAMRA-3′ [for humans]; 5′-FAM-ACGCCTCTGGTTTTTGTAAAGGTGCTCACT-TAMRA-3′ [for rhesus macaques]), and 0.125 μl of platinum Taq polymerase. Platinum Taq was activated at 95°C for 5 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min were performed. A standard curve using serial dilutions of quantitated numbers of plasmids containing signal joint TREC fragment for human TREC or monkey TREC was established and run with each assay. TREC copy numbers were calculated with the software provided with the ABI Prism 5700 system. Each sample was run in duplicate, and mean TREC values and starting cell numbers were used to calculate the percentage of CD4+ or CD8+ T lymphocytes containing TRECs. Values below the limit of detection were assigned values midway between 0 and the lower limit of detection (100 copies), and TREC copy numbers higher than the numbers of cells in each PCR (determined by cell count) were capped at the number of cells.

Cytokine levels.

Plasma levels of IL-7 were quantified using a high-sensitivity enzyme immunoassay that measures both free IL-7 and IL-7 bound to carrier proteins or IL-7 soluble receptors (Quantikine HS IL-7 immunoassay kit; R&D Systems). Specimens for which the values were above the level of detection were diluted and reassayed. IL-7 measurements were performed on plasma samples from a larger subset of the same cohort of children with measles (n = 49) and controls (n = 18) that included all samples available from the patients used for the TREC analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables not normally distributed were compared by using the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. Data analysis was performed using STATA release 6 statistical software (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Phenotypic characterization of circulating lymphocytes.

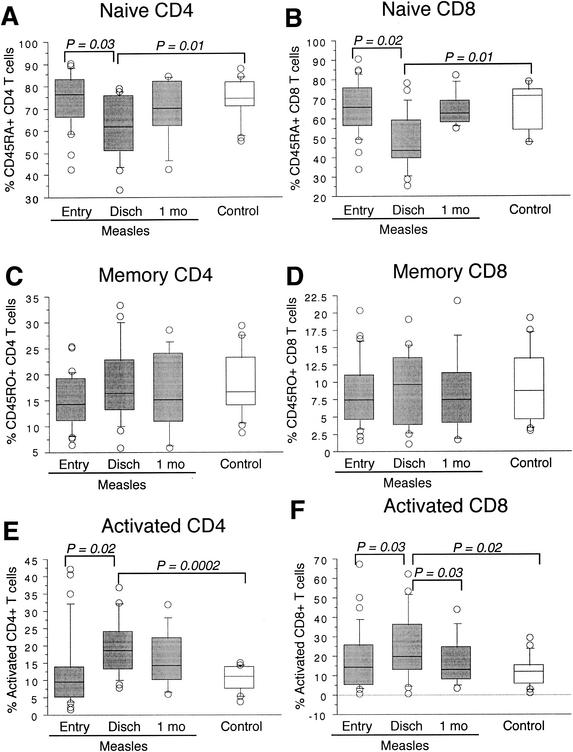

Naïve (CD45RA+, CD62L+) and memory (CD45RO+, CD25−, CD69−, HLA-DR−) subsets of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes were measured by flow cytometry in 30 children with measles (median age, 11 months; interquartile range [IQR] = 9 to 56; 53% boys) and 17 healthy control children (median age, 26.5 months; IQR = 12.5 to 37.5; 44% boys). Memory cells were defined as CD45RO+ lymphocytes without expression of the activation markers CD25, CD69, or HLA-DR, to exclude activated lymphocytes not fully committed to a memory cell phenotype. Percentages rather than absolute numbers are graphically represented and used for statistical analysis because of the lymphopenia that occurs at the time of the measles rash (31); however, median absolute lymphocyte counts are also presented in Table 1. The percentages of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in children with measles at study entry (median 4 days after onset of rash; IQR = 3 to 5) did not differ significantly from values for control children (Fig. 1A and B). However, percentages of naive CD4+ (median = 61%; IQR = 51 to 76%) and CD8+ T lymphocytes (median = 48%; IQR = 44 to 65%) at hospital discharge (median 8 days after onset of rash; IQR = 6 to 9) were significantly decreased compared to values at study entry (median naïve CD4+ = 76%, IQR = 66 to 83%; median naïve CD8+ = 65%, IQR = 56 to 76%; P = 0.02 and P = 0.03, respectively) and of control children (median naïve CD4+ lymphocytes = 74%, IQR = 71 to 81%; median naïve CD8+ lymphocytes = 71%, IQR = 55 to 74%; P = 0.01 for both). Naïve T-lymphocyte percentages returned to baseline at the 1-month follow-up visit (median 40 days after onset of rash; IQR = 40 to 41). The percentages of circulating memory T lymphocytes did not change significantly during the acute or convalescent phase of measles and were not different than values for control children (Fig. 1C and D).

TABLE 1.

CD4+ and CD8+ naïve (CD45RA+, CD62L+), memory (CD45RO+, CD25−, CD69−, HLA-DR−), and activated (CD25+, CD69+, or HLA-DR+) lymphocytes in measles patients at entry, discharge, and 1-month follow-up and in healthy control childrena

| Group | n | Total lymphocytes | Naïve lymphocytes

|

Memory lymphocytes

|

Activated lymphocytes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ | CD8+ | |||

| Entry | 20 | 3,261 (2,340-4,764) | 658 (501-932) | 456 (324-741) | 116 (80-229) | 55 (18-101) | 77 (28-130) | 87 (24-156) |

| Discharge | 17-18 | 6,825 (4,675-8,712) | 1,061 (627-1,515) | 911 (539-1,459) | 283 (206-507) | 110 (78-205) | 396 (226-696) | 251 (133-567) |

| Follow-up | 9 | 5,130 (4,368-6,205) | 1,126 (911-1,764) | 934 (658-1,081) | 309 (147-422) | 114 (68-127) | 218 (155-329) | 231 (61-260) |

| Control | 16 | 7,084 (4,586-9,422) | 1,314 (1,013-2,150) | 1,003 (493-1,522) | 402 (223-462) | 105 (62-219) | 228 (122-254) | 223 (86-446) |

Data are median absolute counts (number of lymphocytes per microliter of blood), with the IQR shown in parentheses.

FIG. 1.

Box plots of the percent naïve, memory, and activated CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in children with measles and control children. Percent CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T lymphocytes with naïve phenotype (CD45RA+, CD62L+), percent CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T lymphocytes with memory phenotype (CD45RO+, CD25−, CD69−, HLA-DR2+), and percent CD4+ (E) and CD8+ (F) T lymphocytes with activated phenotype (CD25+, CD69+, or HLA-DR+) in children with measles at study entry (n = 30), hospital discharge (n = 19 to 20), and 1-month follow-up (n = 10) and in control children (n = 17). P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test.

The percentage and number of activated (CD25+, CD69+ or HLA-DR+) CD4+ (median = 18%; IQR = 13 to 24%; P = 0.0002) and CD8+ (median = 20%; IQR = 13 to 36%; P = 0.02) lymphocytes at the time of hospital discharge were increased in children with measles compared to values of control children (CD4+ median = 11%, IQR = 9 to 14%; CD8+ median = 12%, IQR = 6 to 15%) but were comparable at study entry and 1-month follow-up (Fig. 1E and F). Percentages and numbers of activated T lymphocytes increased from study entry to hospital discharge for both CD4+ (median entry CD4+ = 9%; IQR = 5 to 14%; P = 0.02) and CD8+ T lymphocytes (median CD8+= 14%; IQR = 5 to 25%; P = 0.03), concurrent with the decrease in the percentage of naïve lymphocytes. The percentages of activated CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes both returned to baseline levels by the 1-month follow-up visit (Fig. 1E and F).

TREC levels.

TREC levels were measured in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from children with measles at study entry (n = 29), hospital discharge (n = 17), and at 1-month follow-up (n = 10) and compared to levels from 11 healthy age-matched controls (Fig. 2). At study entry, median TREC levels in both CD4+ (47,000 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 10,000 to 273,279 TRECs/106 cells) and CD8+ lymphocytes (343,992 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 7,082 to 1,000,000 TRECs/106 cells) were higher, although not significantly, than controls (20,998 TRECs/106 CD4+ cells, IQR = 7,422 to 72,817 TRECs/106 cells; 51,079 TRECs/106 CD8+ cells, IQR = 12,741 to 193,649 TRECs/106 cells; P = 0.14 and P = 0.22, respectively) (Fig. 2A). CD4+ TREC levels were significantly elevated at hospital discharge in children with measles (median = 132,410 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 38,000 to 355,206 TRECs/106 cells) compared to levels in control children (P = 0.05) and remained elevated at the 1-month follow-up visit (Fig. 2A) (median = 115,416 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 22,505 to 411,450 TRECs/106 cells; P = 0.06). The CD8+ TREC levels were significantly higher at study entry than at hospital discharge (median = 89,728 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 28,068 to 252,881 TRECs/106 cells; P = 0.02) and the 1-month follow-up visit (median = 33,943 TRECs/106 cells; IQR = 27,000 to 55,123 TRECs/106 cells; P = 0.04), at which time they were equivalent to levels in the control children (Fig. 2B). No age-related changes in TREC levels were observed in our cohort of children with measles, as the majority of children were less than 2 years of age.

FIG. 2.

Box plots of the log number of TRECs per 106 CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T lymphocytes in children with measles and control children. Entry, study entry; Disch, hospital discharge; 1 mo, 1-month follow-up. P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test.

IL-7.

Thymocyte development is dependent on several growth factors, but particularly on IL-7, a hematopoietic cytokine produced by the liver, gastrointestinal epithelia, and thymic stromal cells. Plasma IL-7 levels were elevated in children with measles compared to levels in control children (median = 4.4 pg/ml; IQR = 1.2 to 8.6 pg/ml) at study entry (median = 12.3 pg/ml; IQR = 5.8 to 16 pg/ml; P = 0.0006), hospital discharge (median = 9.6 pg/ml; IQR = 4.8 to 12.9 pg/ml; P = 0.007), and at 1-month follow-up (median = 8.7 pg/ml; IQR = 4.2 to 14.9 pg/ml; P = 0.01) (Fig. 3). Levels of IL-7 were inversely correlated with absolute numbers of naïve CD4+ (Spearman's rho = −0.53; P = 0.05) and total CD4+ (Spearman's rho = −0.52; P = 0.03) T lymphocytes in measles patients at hospital discharge.

FIG. 3.

Box plots of plasma IL-7 levels in children with measles and control children. Group sizes were as follows: study entry (n = 49), hospital discharge (n = 45), 1-month follow-up (n = 31), and controls (n = 18). P values were calculated by using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Thymic function in rhesus macaques with measles.

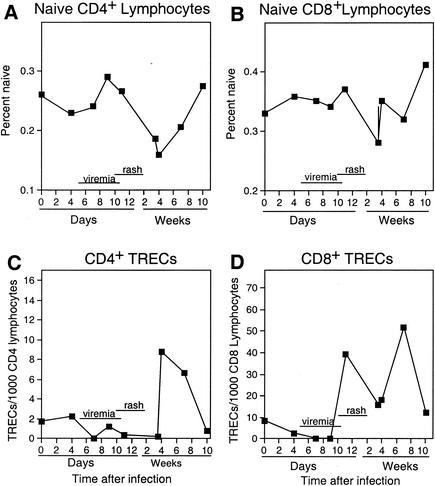

To assess thymic function before, during, and after measles virus infection, TREC levels and naïve (CD45RA+) CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte populations were measured in two rhesus monkeys infected with a wild-type strain of measles virus (Fig. 4). The development of a measles rash in experimentally infected rhesus monkeys, which occurs 10 to 14 days after inoculation, correlates with the entry time point in measles-infected children. Percentages of CD4+ naïve (CD45RA+) T lymphocytes in the peripheral circulation declined 11 to 24 days after infection and returned to baseline levels by day 70 following infection (Fig. 4A), which approximately correlates to the 1-month follow-up time point in children. Percentages of CD8+ naïve T lymphocytes declined slightly 24 days after infection, but quickly returned to or above baseline levels. The TREC levels in measles virus-infected monkeys decreased to levels below baseline by day 7 after infection (during the viremia) in both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte populations (Fig. 4C and D). CD4+ T-lymphocyte TREC levels increased substantially during the convalescent phase of infection (between days 24 and 49), returning to baseline by day 70 (Fig. 4C). CD8+ T lymphocyte TREC levels also increased, beginning 11 days after infection, and remained elevated until 70 days after infection, when numbers decreased to baseline (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Mean percent CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T lymphocytes with naïve phenotype (CD45RA+) and TRECs per 103 CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) lymphocytes during acute and convalescent phases of measles in two rhesus monkeys.

DISCUSSION

The percentage of circulating naïve T lymphocytes decreased during acute measles in both hospitalized children and experimentally infected monkeys, while the percentage of activated T lymphocytes increased in measles virus-infected children, consistent with the induction of an adaptive immune response. The TREC content of T lymphocytes, a measure of recent thymic emigrants, increased above baseline levels in monkeys and above control levels in children after the onset of measles virus rash. Because peripheral T-cell proliferation lowers TREC concentration (18, 47), the actual thymic output during measles may be significantly greater than that suggested by TREC content alone. Plasma IL-7, a cytokine known to be a potent stimulator of thymic output (28) and important in maintaining T-lymphocyte homeostasis (15, 37), was elevated at the time of the rash and for at least 1 month after hospital discharge in measles virus-infected children. These observations suggest temporal changes in thymic function during the acute and convalescent stages of measles virus infection but do not support a role for decreased thymic output as a possible cause of measles virus-induced immunosuppression.

The immune response to many acute viral infections results in expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, resulting in a pool of effector cells responsible for viral clearance (17). During acute infection, naïve T lymphocytes likely accumulate in secondary lymphoid tissue and are released into the circulation after activation (33). The decreased percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes with naïve cell phenotypes at hospital discharge in Zambian children with measles is consistent with this model and with previous observations in children with measles (1). By hospital discharge, peripheral blood lymphocyte counts returned to normal levels (31) and percentages of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in the circulation were increased. IL-7, which remained elevated in measles at follow-up, has been implicated in the development and maintenance of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes from activated CD8+ T-lymphocyte pools (32).

Levels of IL-7 are inversely related to CD4+ cell counts (15, 24) and TREC levels (27) in HIV-infected individuals. In children with measles, plasma levels of IL-7 also were inversely correlated with the number of total and naïve CD4+ cells, but they were directly correlated with TREC levels. The reason for the difference may be the fact that HIV results in a chronic infection in which direct infection of CD4+ T lymphocytes (16) and thymocytes (7, 21) is at least partially responsible for T-lymphocyte depletion. After successful treatment, and partial restoration of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts, TREC levels increase (9, 14, 48) and IL-7 levels decline (12, 24). Measles is an acute viral illness in which the transient lymphopenia is likely a result of lymphocyte trafficking to secondary lymphoid tissue (31) and not due to direct viral infection of lymphocytes. As IL-7 acts as an important regulator of T-lymphocyte homeostasis (15, 27, 37) and exogenous IL-7 leads to increases in TRECs (28), the elevation of IL-7 following measles virus infection could be a stimulus for the increased thymic output in response to peripheral lymphopenia or an early decline in thymic output.

Interestingly, different patterns of TREC levels were observed in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. TREC levels remained significantly elevated in CD4+ lymphocytes compared to healthy controls at 1 month following hospital discharge, while levels in CD8+ T lymphocytes returned to levels in control children after the acute phase of illness. In mice, the thymus produces considerably more CD4+ T lymphocytes than CD8+ T lymphocytes, with a correction in the ratio after export (6). This is thought to be due to limited major histocompatibility complex class I, but not class II, selection in the thymus (8). Maintenance of CD4+ naïve lymphocyte populations requires secondary lymphoid tissue for homeostatic regulation, whereas CD8+ T lymphocytes rely on survival and proliferation signals from the periphery (11). As the CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte pools are regulated independently, acute infection could alter the normal homeostatic production or survival mechanisms for CD4+ T lymphocytes differently than that of the CD8+ T-lymphocyte population. Preferential apoptotic cell death in the CD4+ subpopulation of lymphocytes would lead to sustained elevations in the percentages of TREC-positive cells, as the dying cells would be more likely to be activated and not recent thymic emigrants. In addition, measles virus is controlled by CD8+, major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocytes (20, 26, 29, 40), and increased proliferation of the CD8+ lymphocyte compartment could lead to dilution of the TREC-containing CD8+ lymphocytes. In support of this hypothesis, a depressed CD4+/CD8+ ratio was noted in measles virus-infected Zambian children compared to healthy controls (31).

Measles virus infects thymic epithelial cells, and thymic involution has been observed as an acute consequence of measles (4, 44). In the SCID-hu thymic implant model, measles virus induces thymocyte loss by infection of the thymic epithelial cells (4). This finding is in contrast to models of HIV, in which thymocyte loss is partially due to direct infection of thymocytes (7, 21). While there is no evidence for a decrease in thymic output as a consequence of measles virus infection, disrupted thymic stroma could interfere with proper thymocyte maturation and selection and result in the premature release of thymocytes. Increased production and release of T lymphocytes from the thymus could be associated with impaired T-lymphocyte selection, increasing the possibility of circulating autoreactive or proliferation-impaired T-lymphocyte clones.

The increase in circulating TRECs and IL-7 suggests increased thymic output during acute and convalescent measles and may represent a homeostatic mechanism responsible for replenishing and maintaining naïve T-lymphocyte populations during and after acute viral infection. These findings do not support the hypothesis that decreased thymic output is responsible for the lymphopenia in acute measles or the subsequent suppression of cellular immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zaza Ndhlovu for valuable assistance with sample collection and processing and Pratip Chattopadhyay and Brenna Hill for advice on the TREC assays. We also thank N. P. Luo, L. Munkonkange, E. M. Chomba, Evans Mpabalwani, Gina Mulundu, and Francis Kasolo for facilitating research at the Virology Laboratory and University Teaching Hospital in Zambia; the laboratory and nursing staff in Zambia for work with patient recruitment and sample processing; and the Japan International Cooperation Agency for generously allowing the use of laboratory facilities.

This work was supported by research grant AI 23047 from the National Institutes of Health (D.E.G.); the World Health Organization (D.E.G.); Wyeth-Lederle Vaccines and a Pediatrics Young Investigator Award in Vaccine Development of the Infectious Disease Society of America (W.J.M.); and an Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation Student Award (S.R.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Addae, M. M., Y. Komada, X. L. Zhang, and M. Sakurai. 1995. Immunological unresponsiveness and apoptotic cell death of T cells in measles virus infection. Acta Paediatr. Jpn. 37:308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akramuzzaman, S. M., F. T. Cutts, J. G. Wheeler, and M. J. Hossain. 2000. Increased childhood morbidity after measles is short-term in urban Bangladesh. Am. J. Epidemiol. 151:723-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arneborn, P., and G. Biberfeld. 1983. T-lymphocyte subpopulations in relation to immunosuppression in measles and varicella. Infect. Immun. 39:29-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auwaerter, P. G., H. Kaneshima, J. M. McCune, G. Wiegand, and D. E. Griffin. 1996. Measles virus infection of thymic epithelium in the SCID-hu mouse leads to thymocyte apoptosis. J. Virol. 70:3734-3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auwaerter, P. G., P. A. Rota, W. R. Elkins, R. J. Adams, T. DeLozier, Y. Shi, W. J. Bellini, B. R. Murphy, and D. E. Griffin. 1999. Measles virus infection in rhesus macaques: altered immune responses and comparison of the virulence of six different virus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 180:950-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berzins, S. P., R. L. Boyd, and J. F. A. P. Miller. 1998. The role of the thymus and recent thymic migrants in the maintenance of the adult peripheral lymphocyte pool. J. Exp. Med. 187:1839-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonyhadi, M. L., L. Rabin, S. Salimi, D. A. Brown, J. Kosek, J. M. McCune, and H. Kaneshima. 1993. HIV induces thymus depletion in vivo. Nature 363:728-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capone, M., P. Romagnoli, F. Beermann, H. R. MacDonald, and J. P. van Meerwijk. 2001. Dissociation of thymic positive and negative selection in transgenic mice expressing major histocompatibility complex class I molecules exclusively on thymic cortical epithelial cells. Blood 97:1336-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavan, S., B. Bennuri, M. Kharbanda, A. Chandrasekaran, S. Bakshi, and S. Pahwa. 2001. Evaluation of T cell receptor gene rearrangement excision circles after antiretroviral therapy in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1445-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chino, F., H. Kodama, T. Ohkawa, and Y. Egashira. 1979. Alterations of the thymus and peripheral lymphoid tissues in fatal measles. A review of 14 autopsy cases. Acta Pathol. Jpn. 29:493-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai, Z., and F. G. Lakkis. 2001. Cutting edge: secondary lymphoid organs are essential for maintaining the CD4, but not CD8, naive T cell pool. J. Immunol. 167:6711-6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darcissac, E. C., V. Vidal, X. De La Tribonniere, Y. Mouton, and G. M. Bahr. 2001. Variations in serum IL-7 and 90K/Mac-2 binding protein (Mac-2 BP) levels analysed in cohorts of HIV-1 patients and correlated with clinical changes following antiretroviral therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 126:287-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Villartay, J. P., D. Mossalayi, R. de Chasseval, A. Dalloul, and P. Debre. 1991. The differentiation of human pro-thymocytes along the TCR-alpha/beta pathway in vitro is accompanied by the site-specific deletion of the TCR-delta locus. Int. Immunol. 3:1301-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douek, D. C., R. D. McFarland, P. H. Keiser, E. A. Gage, J. M. Massey, B. F. Haynes, M. A. Polis, A. T. Haase, M. B. Feinberg, J. L. Sullivan, B. D. Jamieson, J. A. Zack, L. J. Picker, and R. A. Koup. 1998. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature 396:690-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry, T. J., E. Connick, J. Falloon, M. M. Lederman, D. J. Liewehr, J. Spritzler, S. M. Steinberg, L. V. Wood, R. Yarchoan, J. Zuckerman, A. Landay, and C. L. Mackall. 2001. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood 97:2983-2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi, R. T., B. K. Chen, S. E. Straus, J. K. Dale, M. J. Lenardo, and D. Baltimore. 1998. HIV-1 directly kills CD4+ T cells by a Fas-independent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 187:1113-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldrath, A. W., and M. J. Bevan. 1999. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature 402:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazenberg, M. D., S. A. Otto, J. W. Cohen Stuart, M. C. Verschuren, J. C. Borleffs, C. A. Boucher, R. A. Coutinho, J. M. Lange, T. F. Rinke de Wit, A. Tsegaye, J. J. van Dongen, D. Hamann, R. J. de Boer, and F. Miedema. 2000. Increased cell division but not thymic dysfunction rapidly affects the T-cell receptor excision circle content of the naive T cell population in HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 6:1036-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch, R. L., D. E. Griffin, R. T. Johnson, S. J. Cooper, I. Lindo de Soriano, S. Roedenbeck, and A. Vaisberg. 1984. Cellular immune responses during complicated and uncomplicated measles virus infections of man. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 31:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaye, A., A. F. Magnusen, and H. C. Whittle. 1998. Human leukocyte antigen class I- and class II-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to measles antigens in immune adults. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1282-1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneshima, H., L. Su, M. L. Bonyhadi, R. I. Connor, D. D. Ho, and J. M. McCune. 1994. Rapid-high, syncytium-inducing isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 induce cytopathicity in the human thymus of the SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 68:8188-8192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Campion, A., C. Bourgeois, F. Lambolez, B. Martin, S. Leaument, N. Dautigny, C. Tanchot, C. Penit, and B. Lucas. 2002. Naive T cells proliferate strongly in neonatal mice in response to self-peptide/self-MHC complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4538-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livak, F., H. T. Petrie, I. N. Crispe, and D. G. Schatz. 1995. In-frame TCR delta gene rearrangements play a critical role in the alpha beta/gamma delta T cell lineage decision. Immunity 2:617-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastroianni, C. M., G. Forcina, G. d'Ettorre, M. Lichtner, F. Mengoni, C. D'Agostino, and V. Vullo. 2001. Circulating levels of interleukin-7 in antiretroviral-naive and highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated HIV-infected patients. HIV Clin. Trials 2:108-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moench, T. R., D. E. Griffin, C. R. Obriecht, A. J. Vaisberg, and R. T. Johnson. 1988. Acute measles in patients with and without neurological involvement: distribution of measles virus antigen and RNA. J. Infect. Dis. 158:433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mongkolsapaya, J., A. Jaye, M. F. Callan, A. F. Magnusen, A. J. McMichael, and H. C. Whittle. 1999. Antigen-specific expansion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in acute measles virus infection. J. Virol. 73:67-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napolitano, L., R. M. Grant, S. G. Deeks, D. Schmidt, S. C. De Rosa, L. A. Herzenberg, B. G. Herndier, J. Andersson, and J. M. McCune. 2001. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nat. Med. 7:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto, Y., D. C. Douek, R. D. McFarland, and R. A. Koup. 2002. Effects of exogenous interleukin-7 on human thymus function. Blood 99:2851-2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Permar, S. R., S. A. Klumpp, K. G. Mansfield, W. K. Kim, D. A. Gorgone, M. A. Lifton, K. C. Williams, J. E. Schmitz, K. A. Reimann, M. K. Axthelm, F. P. Polack, D. E. Griffin, and N. L. Letvin. 2003. Role of CD8+ lymphocytes in control and clearance of measles virus infection of rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 77:4396-4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirquet, C. V. 1908. Verhalten der Kutanen Tuberkulin-Reaktion Wahrend der Masern. Deutsch. Med. Wochenschr. 34:1297-1300. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryon, J. J., W. J. Moss, M. Monze, and D. E. Griffin. 2002. Functional and phenotypic changes in circulating lymphocytes from hospitalized Zambian children with measles. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:994-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schober, S. L., C. T. Kuo, K. S. Schluns, L. Lefrancois, J. M. Leiden, and S. C. Jameson. 1999. Expression of the transcription factor lung Kruppel-like factor is regulated by cytokines and correlates with survival of memory T cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 163:3662-3667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sprent, J., and D. F. Tough. 2001. T cell death and memory. Science 293:245-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starr, S., and S. Berkovich. 1964. Effects of measles, gamma-globulin-modified measles and vaccine measles on tuberculin test. N. Engl. J. Med. 270:386-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda, S., H. R. Rodewald, H. Arakawa, H. Bluethmann, and T. Shimizu. 1996. MHC class II molecules are not required for survival of newly generated CD4+ T cells, but affect their long-term life span. Immunity 5:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamashiro, V. G., H. H. Perez, and D. E. Griffin. 1987. Prospective study of the magnitude and duration of changes in tuberculin reactivity during uncomplicated and complicated measles. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 6:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan, J. T., E. Dudl, E. LeRoy, R. Murray, J. Sprent, K. I. Weinberg, and C. D. Surh. 2001. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8732-8737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanchot, C., and B. Rocha. 1997. Peripheral selection of T cell repertoires: the role of continuous thymus output. J. Exp. Med. 186:1099-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valentin, H., O. Azocar, B. Horvat, R. Williems, R. Garrone, A. Evlashev, M. L. Toribio, and C. Rabourdin-Combe. 1999. Measles virus infection induces terminal differentiation of human thymic epithelial cells. J. Virol. 73:2212-2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Binnendijk, R. S., M. C. Poelen, K. C. Kuijpers, A. D. Osterhaus, and F. G. Uytdehaag. 1990. The predominance of CD8+ T cells after infection with measles virus suggests a role for CD8+ class I MHC-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in recovery from measles. Clonal analyses of human CD8+ class I MHC-restricted CTL. J. Immunol. 144:2394-2399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verschuren, M. C., I. L. Wolvers-Tettero, T. M. Breit, J. Noordzij, E. R. van Wering, and J. J. van Dongen. 1997. Preferential rearrangements of the T cell receptor-delta-deleting elements in human T cells. J. Immunol. 158:1208-1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward, B. J., R. T. Johnson, A. Vaisberg, E. Jauregui, and D. E. Griffin. 1991. Cytokine production in vitro and the lymphoproliferative defect of natural measles virus infection. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 61:236-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wesley, A., H. M. Coovadia, and L. Henderson. 1978. Immunological recovery after measles. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 32:540-544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White, R. G., and J. F. Boyd. 1973. The effect of measles on the thymus and other lymphoid tissues. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 13:343-357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamanouchi, K., F. Chino, F. Kobune, H. Kodama, and T. Tsuruhara. 1973. Growth of measles virus in the lymphoid tissues of monkeys. J. Infect. Dis. 128:795-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasunaga, J., T. Sakai, K. Nosaka, K. Etoh, S. Tamiya, S. Koga, S. Mita, M. Uchino, H. Mitsuya, and M. Matsuoka. 2001. Impaired production of naive T lymphocytes in human T-cell leukemia virus type I-infected individuals: its implications in the immunodeficient state. Blood 97:3177-3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye, P., and D. E. Kirschner. 2002. Reevaluation of T cell receptor excision circles as a measure of human recent thymic emigrants. J. Immunol. 168:4968-4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, L., S. R. Lewin, M. Markowitz, H. H. Lin, E. Skulsky, R. Karanicolas, Y. He, X. Jin, S. Tuttleton, M. Vesanen, H. Spiegel, R. Kost, J. van Lunzen, H. J. Stellbrink, S. Wolinsky, W. Borkowsky, P. Palumbo, L. G. Kostrikis, and D. D. Ho. 1999. Measuring recent thymic emigrants in blood of normal and HIV-1-infected individuals before and after effective therapy. J. Exp. Med. 190:725-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]