Abstract

Osteoporosis is a common and debilitating condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The efficacy and safety of oral bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis are well established. However, patient adherence and persistence on treatment are suboptimal. This randomised open-label multi-centre study of 6-months’ duration compared persistence on treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis receiving either once-monthly ibandronate plus a patient support programme (PSP), or once-weekly alendronate. To avoid falsely elevated persistence rates often associated with clinical trials, the study was designed to reflect everyday clinical practice in the UK and follow-up visits were limited to be consistent with the primary care setting. Analysis of the primary endpoint showed that persistence was significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group compared with the alendronate group (p < 0.0001). The estimated proportion of patients persisting with treatment at 6 months was 56.6% (306/541) and 38.6% (198/513) in the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups, respectively. Therefore, compared with alendronate, there was a 47% relative improvement in the proportion of patients persisting with treatment in the ibandronate/PSP group. Secondary endpoint measurements of adherence (e.g. proportion of patients remaining on treatment at study end; proportion of patients discontinuing from the study) were also significantly different in favour of ibandronate plus patient support. In summary, the PERSIST study demonstrated that persistence on treatment was increased in patients receiving once-monthly ibandronate plus patient support compared with once-weekly alendronate. Increased persistence on bisphosphonate treatment is expected to improve patient outcomes and decrease the social and economic burden of osteoporosis.

Keywords: Adherence, alendronate, bisphosphonates, ibandronate, osteoporosis, persistence

Introduction

‘The number one problem in treating illness today is the failure of the patient to take prescription medications correctly’ (1). This statement from a recent American Heart Association report clearly highlights the impact of poor treatment adherence on patient health. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in developed countries, just 50% of patients with chronic diseases adhere to their recommended treatment regimens (2). Consequently, interventions to improve adherence may have a far greater impact on patient health than advances in medical therapies (2).

Varying terminology is used to describe the extent to which patients adhere to treatment (e.g. adherence, compliance, persistence). Although the terms adherence and compliance are often used interchangeably, adherence requires a patient's agreement to treatment recommendations and has been defined by the WHO as ‘the extent to which a person's behaviour – taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider’ (2). The accumulation of time from initiation to discontinuation of treatment is referred to as ‘persistence’ (3).

Osteoporosis is a common, chronic – but frequently asymptomatic – disease of the skeleton associated with low rates of treatment adherence and persistence (4,5). Despite its sometime ‘silent’ nature, osteoporosis is a debilitating condition exposing patients to an increased risk of serious fragility fractures and associated morbidity and mortality (6). Poor persistence with osteoporosis medications increases fracture risk, impairs patients’ quality of life and raises both direct and indirect healthcare costs (5).

Oral bisphosphonates are usually the first-line treatment option for postmenopausal osteoporosis, and their effectiveness in increasing bone mineral density (BMD), normalising bone turnover and reducing the risk of fracture is well established (6). However, the usefulness of bisphosphonates in clinical practice is often compromised by poor adherence and persistence on treatment (5). In the UK, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) acknowledges the importance of adherence, and states that an ‘unsatisfactory response to bisphosphonate treatment’ involves the occurrence of another fragility fracture despite full adherence with treatment (7).

Complex dosing instructions are necessary to maximise the bioavailability of bisphosphonates and reduce the risk of adverse events, and there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that reduced adherence to these agents is associated with increased dosing complexity (4,5,8,9). Interestingly, studies in other disease states have shown that reducing the complexity and frequency of dosing regimens improves adherence and persistence (10,11).

Attempts to improve adherence in patients with osteoporosis include the development of weekly and monthly oral bisphosphonates that require less frequent dosing than standard once-daily formulations. Indeed, the once-weekly formulation of alendronate is associated with improved adherence compared with daily alendronate (12). However, adherence to weekly bisphosphonates remains suboptimal, with studies reporting one-year adherence and persistence rates of <50% (12,13). In a longitudinal cohort study of over 200,000 women, only 25% of patients who were new to bisphosphonate treatment and received prescriptions for weekly alendronate or risedronate, achieved levels of adherence adequate to ensure anti-fracture efficacy (13). The DIN-LINK general practice database (CompuFile Ltd, Woking, UK) compiles data from longitudinal patient records across the UK, and reports ‘real-life’ persistence rates of 50–55% 6 months after the initiation of treatment with weekly alendronate (14).

The once-monthly oral formulation of the bisphosphonate ibandronate (also known as ibandronic acid) has been shown to be as effective and well-tolerated as once daily ibandronate (15). In a recent randomised cross-over study, 66% of patients preferred the once-monthly dosing regimen of ibandronate to the once-weekly dosing regimen of alendronate (16). Although it is possible that once-monthly treatment regimens may lead to improved persistence, this has not yet been investigated in randomised controlled studies.

To improve the effectiveness of bisphosphonate treatment, a patient support programme for once-monthly ibandronate has been developed. This programme is currently available, free-of-charge, to all patients prescribed ibandronate in the UK. The PERSIST study (PERsistence Study of Ibandronate verSus alendronaTe) was a randomised, open-label multi-centre study of 6 months’ duration designed to assess persistence on treatment within a ‘real-life’ primary care setting in the UK. The objective of PERSIST was to determine whether once-monthly dosing with ibandronate, coupled with the ibandronate patient support programme, would improve persistence on treatment compared with once-weekly alendronate.

Methods

Patients

Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis were eligible for inclusion in the study. Diagnoses of osteoporosis were based upon the clinical judgement of each patient's primary care General Practitioner (GP). Assessment of BMD by densitometry was not compulsory. Eligible patients were required to be independent and self-caring, and able to comply with bisphosphonate dosing requirements. In particular, patients had to be able to observe a pre- and post-dose fasting interval and maintain an upright posture for 1 h following bisphosphonate dosing. The main exclusion criteria were: previous or current treatment with a bisphosphonate; hypersensitivity to bisphosphonates; and abnormalities of the oesophagus causing delayed oesophageal emptying.

The study protocol and any written information to be provided to patients were submitted to an Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) complying with local regulatory requirements. Written approval for the study was obtained from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the South-East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC), and Local Research Ethics Committees (LRECs) and Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) for each study centre. The study was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design and Treatment

Design

This open-label study was conducted in 103 primary care centres in the UK between 21 January 2005 and 18 January 2006. After a screening period of up to 30 days, eligible patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive either oral ibandronate (150 mg single tablet, once monthly) or oral alendronate (70 mg single tablet, once weekly) for 6 months. Patients assigned to receive ibandronate were also enrolled into the patient support programme, and constituted the ‘ibandronate/PSP group’. Randomisation was stratified according to age (<70 years of age and ≥70 years of age) and was achieved using a randomised allocation schedule (based on block randomisation within age strata), with details provided to investigators in envelopes.

The study protocol allowed randomisation to be performed on the same day as the initial screening visit, providing the patient had sufficient time to consider participating in the study. In addition to the screening and randomisation visits, only one further visit was planned; this was a final visit at the end of the study at 6 months. In keeping with everyday clinical practice, GPs and/or patients could plan intermediate visits according to personal needs and practice policies.

Treatment

To reflect a ‘real-life’ setting, study medication was obtained through dispensing pharmacists. A GP at each study centre was linked to a nominated pharmacist. For each patient, the GP completed, and retained on file, a proforma indicating treatment assignment (ibandronate/PSP or alendronate). Patients subsequently presented identical copies of the proforma to the nominated pharmacists who then dispensed 1-month's study medication. Every month, up to the end of the study at six months, patients could obtain proformas using the normal repeat prescribing process employed by each GP's practice (e.g. telephoning the practice reception or a practice nurse). Patients then ‘filled the prescription’ by providing the proforma to their dispensing pharmacist and obtaining that month's medication. Patients were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Patients were instructed to take ibandronate or alendronate in the morning, after an overnight fast, in an upright position and with a full glass of plain water. Patients were to remain fasting and in an upright position for at least 30 or 60 min after dosing with alendronate and ibandronate respectively. Concomitant treatment with hormone replacement therapy and/or calcium and Vitamin D was permitted; details of all concomitant medications were recorded.

Patient support programme

The dispensing pharmacists were responsible for faxing patients’ contact details to the providers of the ibandronate patient support programme (International SOS Assistance (UK) Ltd, London, UK). This programme is available to all patients prescribed once-monthly ibandronate in the UK; there is no equivalent support programme available to patients prescribed once-weekly alendronate. Therefore, to reflect current UK practice, only patients randomised to receive ibandronate were enrolled into the programme.

Following an initial telephone call, patients enrolled into the patient support programme received a welcome-pack providing basic information about osteoporosis. Between 1 and 3 days prior to each scheduled monthly dose, patients received a telephone call to remind them to take their medication. During each call, patients were provided with relevant dosing instructions, and information about osteoporosis and the importance of long-term adherence to treatment. All telephone contact with patients was carried out by trained nurses. A newsletter was also sent to patients 3 months after enrolment into the programme. Patients were free to withdraw from the patient support programme after 3 months of treatment.

Study Endpoints

Primary endpoint

The primary endpoint of the study was persistence on treatment of patients receiving once-monthly ibandronate with the patient support programme vs. that of patients receiving once-weekly alendronate. The measurement of persistence employed during the study was based on the number of consecutive months of study medication dispensed to the patient by the nominated pharmacists (i.e. the number of ‘prescription refills’). Specifically, persistence was defined as the number of days from the date of randomisation to the date of the first failure to persist (i.e. the time-to-failure-to-persist). A patient was classified as failing to persist if she withdrew from the study or missed one prescription cycle. Therefore, a patient who failed to fill 1 month's prescription was considered non-persistent for the remainder of the study, regardless of whether she collected medication for one or more subsequent months.

Patients were allowed a window of ±14 days to fill each month's prescription. The date of failure was defined as the date of the last filled prescription prior to failure plus 30 days, or the date of withdrawal, whichever occurred first.

Secondary endpoints

Secondary endpoints were (i) the number of patients who discontinued treatment; (ii) the number of patients who had at least five of the six prescriptions filled; and (iii) the number of patients remaining on treatment at the end of the study (i.e. patients who had their sixth prescription filled).

Safety Analyses

Investigators were asked to record any adverse event experienced by patients, irrespective of the suspected relationship to treatment. All reported adverse events were recorded and graded according to severity (mild, moderate or severe). The safety population included all randomised patients who provided safety data while receiving study medication.

Adverse event profiles presented are for treatment-emergent adverse events (i.e. adverse events with a recorded start date beyond or equal to the date of randomisation). If the start date of a reported adverse event was missing, this was considered a treatment-emergent adverse event.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on the primary endpoint (persistence on treatment). Assumptions for the persistence rate on alendronate were based on data from the DIN-LINK general practice database showing persistence rates of 50–55% at 6 months for patients in a ‘real-life’ primary care setting during the years 2002 and 2003 (14). It was assumed that, despite the naturalistic design of the study, persistence in the alendronate group would be artificially increased to 60% at 6 months.

Using a log-rank test at a two-sided 5% level of significance, 476 patients per treatment group would be sufficient to detect, with 90% power, a difference between a proportion of persisting patients of 60% in the alendronate group and 70% in the ibandronate/PSP group. This assumed a constant hazard ratio of 1.43 (i.e. patients in the alendronate group were 1.43 times more likely to fail to persist than patients in the ibandronate/PSP group). The planned total number of patients to be recruited for the study was 1000.

Futility analysis

To permit valid interpretation of the persistence data, it was first necessary to determine whether the study accurately reflected routine clinical practice in the UK. A preplanned futility analysis was therefore performed, which sought to compare persistence rates observed at 4 months in the alendronate group with those reported in UK general practice records (DIN-LINK database).

The futility analysis was performed once the 280th alendronate patient had either completed 4 months of treatment or was withdrawn from the study. With a sample size of 280 in the alendronate group, a one-group χ2-test with a 2.5% one-sided significance level would have 80% power to detect the difference between the clinical practice persistence rate (62%) calculated from the record database, and a hypothetically elevated persistence rate of 70% in the alendronate group. The null hypotheses – that the proportion of patients in the alendronate group persisting with treatment was equal to 62%– was rejected if the p-value from a one-sided, one-group proportion test (with a continuity correction) was <0.05. Deviation from persistence rates available from GP record databases would have implied that study participation influenced patient behaviour, and thus rendered the study findings invalid.

Analyses of study endpoints.

Study endpoint analyses were performed for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all patients in the safety population who provided at least one primary endpoint measurement (i.e. had filled at least one prescription).

For the primary endpoint, time-to-failure-to-persist data were used to construct Kaplan–Meier curves for the two treatment groups. The statistical significance of the difference between the distributions of the curves was tested using log-rank and Wilcoxon–Gehan tests. These analyses were performed using SAS® LIFETEST (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). In a second analysis, a Cox's proportional hazards model was fitted to the time-to-failure-to-persist data with adjustments for the stratification variable (patient age). This model was used to compare the likelihood of failure in the two treatment groups.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 1103 patients consented to participate in the study, with 561 and 542 patients randomised to the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups respectively. The safety population included 1077 patients (ibandronate/PSP group, n = 548; alendronate group, n = 529). Persistence data for one patient in the ibandronate/PSP group were unavailable for analysis and this patient was excluded from the ITT population (N = 1076).

Baseline demographics and characteristics were similar between treatment groups (Table 1). Patients were postmenopausal women with a mean age of 67.8 years. T-scores from previous BMD assessments were known for >30% of patients.

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics and characteristics for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population

| Ibandronate/PSP (n = 547) | Alendronate (n = 529) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age [mean (SEM) years] | 67.8 (0.4), n = 541 | 67.8 (0.4), n = 513 |

| Ethnic group, n (%)* | ||

| Caucasian | 533 (98.5) | 507 (98.8) |

| Black | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.8) |

| Oriental | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Other | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| BMD, n (%)* | ||

| Known | 171 (31.9) | 168 (33.1) |

| Not known | 365 (68.1) | 340 (66.9) |

| T-score in patients with known BMD assessment,† mean (SEM) | −2.42 (0.07), n = 171 | −2.45 (0.07), n = 168 |

| Clinically significant findings on physical examination, n (%)* | ||

| Yes | 75 (14.1) | 67 (13.3) |

| No | 457 (85.9) | 436 (86.7) |

| Time since onset of menopause, mean (SEM) years | 21.7 (0.5), n = 382 | 21.8 (0.5), n = 372 |

| Family history of osteoporosis, n (%)* | ||

| Yes | 186 (34.5) | 188 (36.8) |

| No | 353 (65.5) | 323 (63.2) |

| Subjects reporting medical history, n (%)* | 520 (96.3) | 496 (96.7) |

| For patients with medical history, n (%) | ||

| No previous fractures | 288 (55.4) | 275 (55.4) |

| 1 previous fracture | 165 (31.7) | 151 (30.4) |

| 2 previous fractures | 47 (9.0) | 49 (9.9) |

| 3–5 previous fractures | 20 (3.8) | 21 (4.2) |

| For patients with previous fracture(s) | ||

| Time since last fracture, mean (SEM) years | 7.0 (0.6), n = 230 | 7.6 (0.7), n = 220 |

PSP, patient support programme.

Percentages are based on the number of ITT patients for whom relevant data were available.

The site of bone mineral density (BMD) assessment varied and included the spine, hip and forearm.

Futility Analysis

The rate of persistence in the alendronate group at four months (145/278, 52.2%) was not elevated in comparison with rates of persistence to alendronate treatment in routine clinical practice calculated from the DIN-LINK general practice database (62%). The futility analysis confirmed that alendronate persistence rates in the study were statistically different, and slightly lower, than those in clinical practice (z = −3.319; one-sided p = 0.0005). It was therefore considered appropriate to continue with the study.

Persistence on Treatment

Primary endpoint

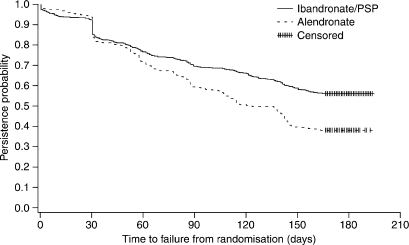

Analysis of the primary endpoint showed that persistence on treatment was significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group compared with the alendronate group. The estimated proportion of patients persisting with treatment at six months was 56.6% (306/541; 95% CI: 52.3%, 60.6%) and 38.6% (198/513; 95% CI: 34.4%, 42.8%) in the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups respectively. Therefore, compared with the alendronate group, there was a 47% relative improvement in the proportion of patients persisting with treatment in the ibandronate/PSP group. Kaplan–Meier curves for the two treatment groups were constructed with the time-to-failure-to-persist data and represent the probability of an individual patient persisting with treatment over time (Figure 1). The distributions of the Kaplan–Meier curves for the two treatment groups were significantly different, with the probability of persistence significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group (p < 0.0001, log-rank and Wilcoxon–Gehan tests).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patients in the ibandronate/patient support programme (PSP) and alendronate groups. Time-to-failure-to-persist data for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population were used to estimate the probability of persistence at each time-point. Data for patients persisting with treatment at the end of the study were censored, to indicate that the period of observation was cut off before the event of interest (e.g. failing to persist with treatment) occurred. The censoring time was defined as the last prescription filled/dispensed plus 30 days

The median time-to-failure-to-persist in the alendronate group was 136 days (95% CI: 111, 142). It was not possible to calculate the median time-to-failure-to-persist for the ibandronate/PSP group because >50% of patients in this group were persistent at the end of the study. The mean (±SEM) time-to-failure-to-persist was 122 (±2.5) and 109 (±2.5) days in the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups respectively.

As indicated in Figure 1, a slightly higher proportion of patients in the alendronate group persisted with treatment during the first month. This initial trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.212), and reversed after 30 days. The probability of persistence was higher in the ibandronate/PSP group for the remainder of the study. For patients who persisted with treatment beyond day 30, the estimated hazard ratio for patients in the ibandronate/PSP group vs. patients in the alendronate group was 0.538 (95% CI: 0.44, 0.66; p < 0.0001). Therefore, beyond day 30, patients in the ibandronate/PSP group were approximately half as likely to fail to persist as patients treated with alendronate.

Secondary endpoints

A total of 241 patients discontinued from the study (Table 2). Significantly more patients discontinued from the study in the alendronate group (134/529, 25.3%) compared with the ibandronate/PSP group (107/547, 19.6%; p = 0.023). The most common reasons for discontinuation were adverse events (n = 127) and patient withdrawal from the study (n = 40).

Table 2.

Patient discontinuations for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population

| Ibandronate/PSP (n = 547) | Alendronate (n = 529) | p-value (χ2test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) patients discontinued from the study | 107 (19.6) | 134 (25.3) | 0.023 |

| Primary reason for discontinuation, n (%) | |||

| Adverse event | 65 (11.9) | 62 (11.7) | 0.934 |

| Withdrew from study | 19 (3.5) | 21 (4.0) | – |

| Administrative reason | 0 (0) | 4 (0.8) | – |

| Protocol violation | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | – |

| Lost to follow-up | 8 (1.5) | 14 (2.6) | – |

| Withdrew consent | 6 (1.1) | 16 (3.0) | – |

| Other | 5 (0.9) | 12 (2.3) | – |

PSP, patient support programme.

The proportion of patients who had at least five of the six prescriptions filled was significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group compared with the alendronate group (p = 0.008; Table 3). Similarly, the proportion of patients who remained on treatment at the end of the study and had their sixth prescription filled was significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group (p = 0.014; Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary endpoints for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population

| Ibandronate/PSP (n = 547) | Alendronate (n = 529) | p-value (χ2test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%)* patients with at least five prescriptions filled | 434 (80.2) | 376 (73.3) | 0.008 |

| No. (%)* patients with sixth prescription filled | 405 (74.9) | 349 (68.0) | 0.014 |

PSP, patient support programme.

Percentages are based on the number of ITT patients for whom relevant data were available.

Persistence stratified by age

Results for the two age strata (<70 years and ≥70 years of age) were similar to those for the whole study cohort. Within both age strata, Kaplan–Meier analyses showed significant differences in the primary endpoint of persistence on treatment in favour of the ibandronate/PSP group (<70 years, p < 0.0006; ≥70 years, p = 0.002; Wilcoxon–Gehan tests). There was no significant difference in the primary endpoint between the two age strata, either before or after day 30 of the study (≤30 days, p = 0.797; >30 days, p = 0.431; Wald test).

Safety

A similar proportion of patients in the ibandronate/PSP group [371/542 (68.5%)] and alendronate group [381/513 (74.3%)] experienced at least one adverse event. The majority of adverse events were mild or moderate in severity. A higher proportion of adverse events were considered possibly related to study treatment in the ibandronate/PSP group [155/904 (17.1%)] compared with the alendronate group [104/892 (11.7%)]. However, similar proportions of adverse events were considered probably related to study treatment [63/904 (7.0%) and 58/892 (6.5%) in the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups respectively]. There was no significant difference between treatment groups in the proportion of patients discontinuing the study because of adverse events (p = 0.934; Table 2).

Treatment-emergent adverse event profiles were comparable between treatment groups (Table 4). Gastrointestinal disorders and musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorders were the most commonly reported adverse events. Overall, similar results were reported in the two age strata (<70 and ≥70 years of age). However, gastrointestinal disorders were reported in a higher proportion of patients aged <70 years compared with patients aged ≥70 years [140/609 (23.0%) and 91/468 (19.4%) respectively].

Table 4.

Adverse events in the safety population. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were defined as adverse events with a recorded start date beyond or equal to the date of randomisation

| Ibandronate/PSP (n = 548) | Alendronate (n = 529) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. patients with at least 1 TEAE | 371 | 380 |

| TEAEs, n (%)* patients | ||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 122 (32.9) | 109 (28.7) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 44 (11.9) | 42 (11.1) |

| Infections and infestations | 103 (27.8) | 111 (29.2) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 123 (33.2) | 131 (34.5) |

| Nervous system disorders | 54 (14.6) | 39 (10.3) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 37 (10.0) | 49 (12.9) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 35 (9.4) | 42 (11.1) |

PSP, patient support programme.

Percentages are based on the number of patients in the safety population with at least one treatment-emergent adverse event. Data are presented for TEAEs occurring in ≥10% of patients who experienced at least one TEAE in either treatment group.

In patients aged <70 years, musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders were more common in the alendronate group [occurring in 74 of a total of 214 patients experiencing treatment-emergent adverse events (34.6%)] compared with the ibandronate/PSP group [63/214 (29.4%)]. However, this trend was reversed in patients aged ≥70 years, with musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders more common in the ibandronate/PSP group compared with the alendronate group [60/157 (38.2%) and 57/166 (34.3%), respectively].

Conclusions

This randomised, controlled study compared persistence on treatment in postmenopausal women receiving monthly ibandronate (150 mg) plus patient support, or weekly alendronate (70 mg). The study was designed to reflect everyday clinical practice and to avoid falsely elevated persistence rates often reported in the clinical trial setting.

The primary endpoint of the study – persistence on treatment – was significantly greater in patients receiving ibandronate plus patient support compared with patients receiving alendronate. By the end of the study at 6 months, there was an 18% absolute difference between the ibandronate/PSP and alendronate groups in the proportion of patients persisting with treatment. With 39% of patients persisting on treatment in the alendronate group at 6 months, this absolute difference represents an approximately 47% improvement in persistence for patients receiving once-monthly ibandronate plus patient support. Indeed, hazard ratio analyses revealed that, from day 30 until the end of the study at 6 months, patients in the ibandronate/PSP group were approximately half as likely to cease treatment compared with patients receiving alendronate. Results were consistent across all age strata.

The definition of persistence employed in the study was stringent but consistent with other similar studies and the DIN-LINK UK general practice database (12,14,17). In PERSIST, patients failing to fill their monthly prescription within 14 days of the expected date were considered non-persistent. A patient who, for example, failed to persist at month 2 but subsequently collected medication as expected during months 3–6, would have been classified as a non-persisting patient from month 2 onwards. Secondary endpoints measuring patient adherence were also employed during this study. The proportion of patients remaining on treatment at the end of the study, estimated from the number of patients refilling a prescription at 6 months, was significantly higher in the ibandronate/PSP group compared with the alendronate group (75% vs. 68%). Similarly, the number of discontinuations (20% vs. 25%) and the number of patients refilling five of the six monthly prescriptions (80% vs. 73%), were also statistically different in favour of patients receiving ibandronate plus patient support.

Cross-study comparisons of persistence rates are invalid unless the definitions of persistence employed are similar. Boccuzzi et al. (17) used a similar definition to that employed in the PERSIST study, and reported persistence rates over 12 months for daily and weekly alendronate of 19% and 22% respectively. Persistence rates at 12 months of 32% and 44% for daily and weekly alendronate were reported by Cramer et al. (12) in another study that employed a similar definition of persistence. Higher rates of persistence at 12 months (67–84%) were reported in a UK study of daily raloxifene treatment; however, persistence was defined less stringently as ‘continuing to take tablets for more than seven of any 14 days immediately before the 1-year visit’ (18).

Tolerability issues, in particularly gastrointestinal adverse events, are a significant cause of early discontinuation from bisphosphonate treatment (5). Both ibandronate and alendronate were well tolerated during the PERSIST study. Unsurprisingly, given the patient population and study medication, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal/connective tissue disorders were the most commonly reported adverse events.

One potential limitation of PERSIST was the 6-month duration of the study. However, data from a GP record database in the UK indicate that rates of persistence on weekly alendronate begin to stabilise approximately 3 months after the start of treatment (14). Indeed, persistence rates in the PERSIST study declined at a slower rate after the third month of treatment. It is not unreasonable to suggest that most of the patients who were persistent with treatment at 6 months were likely to continue with treatment beyond this point.

The efficacy of bisphosphonate treatment was not measured during the PERSIST study. The safety and efficacy of the bisphosphonates are well established (6), and the objective of PERSIST was to measure and compare persistence on treatment of patients receiving two commonly prescribed bisphosphonate preparations. Although persistence rates obtained from prescription data do not equate exactly to rates of patient adherence to medication, the measurement of prescription refills is a well-established method of indirectly monitoring adherence and persistence on treatment. There is no standard method of measuring adherence, and other methods such as the biochemical analysis of drug concentrations in the blood or urine are costly and inconvenient for patients (19).

Compared with clinical practice, adherence to treatment in a clinical trial setting may be enhanced and result in falsely elevated persistence treatment rates. Trial selection criteria may be biased towards patients more likely to adhere to treatment and, once selected, trial patients may be afforded longer consultation times and provided with more information about their medication than patients in clinical practice. The PERSIST study was designed to reflect everyday clinical practice and to minimise the impact of trial participation on persistence rates. Patients requested and obtained each month's medication via a method very similar to that employed in most primary care centres in the UK. The futility analysis showed that, 4 months into the study, persistence in the alendronate group was not elevated compared with ‘real-life’ persistence data from a computerised GP record database.

In keeping with the naturalistic design of the study, patients randomised to receive ibandronate were also enrolled into a patient support programme. This programme is available to all patients in the UK who are prescribed once-monthly ibandronate. Patients enrolling in the programme are provided with monthly reminder telephone calls and are able to obtain advice on osteoporosis and their medication. Patient support programmes are increasingly used to improve adherence and persistence in chronic conditions such as obesity (20), and are consistent with calls to involve patients in any initiative designed to improve treatment adherence (19). In a recent UK study, patient support – in the form of treatment monitoring by nurses – improved adherence by 57% and increased the average length of time patients persisted with treatment by 25% (18). In the same study, monitoring by nurses had a greater impact on adherence and persistence than the provision of bone marker results to patients. To date, there is no patient support programme in the UK for patients prescribed weekly alendronate. In the PERSIST study, enrolment of patients randomised to receive alendronate into a patient support programme would therefore not have reflected UK clinical practice.

Although calculating the effect of increased persistence on fracture risk and other measures of bisphosphonate efficacy was beyond the scope of this 6-month study, the available evidence suggests that adherence to treatment is associated with improved patient outcomes. Various studies have shown that increases in BMD are greater in patients who strictly adhere to oral bisphosphonate regimens (21–23). In a UK-based randomised controlled study, Clowes et al. (18) demonstrated an association between adherence to osteoporosis treatment and positive changes in hip BMD and bone-marker resorption (18). Fracture rates are also lower in patients with osteoporosis who adhere to treatment. Studies in clinical practice showed that patients who adhered to various osteoporosis medications experienced a 16% lower fracture rate and a 24% reduction in fracture risk compared with non-adherent patients (24,25). In another study, adherence to bisphosphonate treatment was associated with a 36% reduction in the relative risk of hip fracture over 2 years (26). As well as improving patient outcomes, increased adherence and persistence is likely to significantly reduce healthcare costs associated with osteoporosis treatment.

In summary, the PERSIST study demonstrated that persistence on treatment was increased in patients receiving once-monthly ibandronate plus patient support compared with once-weekly alendronate. Increased persistence on bisphosphonate treatment in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis is expected to improve patient outcomes and decrease the social and economic burden of this debilitating condition.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to all those who have contributed to the conduct and analysis of the PERSIST study, including the study investigators Lawrence Martin Adler, Paul Ainsworth, Dennis Allin, Moyra Anderson, Margaret Angus, Colin Barrett, Raj Bhargava, Mark Blagden, Kean Blake, Daniel Brandon, Robert Brownlie, Albert Burton, Duncan Burwood, Tom Cahill, William Carr, Robert Cook, Christopher Corbyn, Richard Croft, Caroline Dain, Adrian Darrah, Miles Davidson, Emyr Davies, Lionel Dean, Michael Duckworth, Patrick Eavis, David Eccleston, David Edwards, Tony Egerton, Adam Ellery, Richard Evans, Nicola Evans, Simon Fearns, John Fife, Paul Fletcher, Graham Garrod, Nayeem Ghouri, Caroline Gilchrist, Charles Gogbashian, Stephen Goldberg, Trevor Gooding, Nigel Gough, Alison Graham, Ian Grandison, Carole Groenhuysen, Kevin Gruffydd Jones, Michael Gumbley, Tim Hall, John Ham, Lorna Hamilton, Peter Hardy, Rebecca Hodson, Jean Hodson, John Hole, Keith Holgate, Alan Jackson, Richard James, Neil Jones, Desmond Keating, Neil Kerry, Fiona Kingston, Michael Kirby, Martin Kittel, Krishna Korlipara, John Lakeman, Christopher Langdon, Susan Langridge, Teck Lee, Peter Maksimczyk, Graham Martin, Ian Mason, John McBride, Paul McEleny, Julie McIntyre, George McLaren, Amar Mishra, Mohanda Nair, Mark Norman, Juan Ochoa, Myros Parashchak, Mike Pimm, Jeremy Platt, James Playfair, Dean Price, Ann Robertson, David Russell, John Ryan, Edward Selby, Pauleen Shearer, Andrew Shepherd, Muhammad Siddiq, Hamish Simpson, Andy Smithers, Rory Symons, Julian Thompson, John Tilley, Jitendra Trivedi, Wayne Turner, Martyn Walling, Ann Weaver, Anthony Weaver, Jeremy Wheeler, and Anthony Wright. The assistance of Cristina Ivanescu from Quintiles Strategic Research Services is also gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosures

This research was supported by Roche Products Ltd. Dr Cooper and Dr Brankin have served as speakers, consultants and advisory board members for Roche Products Ltd and GlaxoSmithKline, and have received research funding from Roche Products Ltd. Dr Drake is an employee of Roche Products Ltd.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. 2003. [17 May 2006]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. 2003. [17 May 2006]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chronic_conditions/adherencereport/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Medication Compliance and Persistence Special Interest Group. [17 May 2006]. Available from: http://www.ispor.org/sigs/MCP_accomplishments.asp#definition. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emkey RD, Ettinger M. Improving compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2006;119(Suppl. 1):S18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer JA, Silverman S. Persistence with bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis: finding the root of the problem. Am J Med. 2006;119(Suppl. 1):S12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delmas PD. Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet. 2002;359:2018–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08827-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisal 87 January 2005. Bisphosphonates (Alendronate, Etidronate, Risedronate), Selective Oestrogen Receptor Modulators (Raloxifene) and Parathyroid Hormone (Teriparatide) for the Secondary Prevention of Osteoporotic Fragility Fractures in Postmenopausal Women. [17 May 2006]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/pdf/TA087guidance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H. Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:259–62. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombas C, Hakim C, Zanchetta JR. Compliance with alendronate treatment in an osteoporosis clinic. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;15(Suppl.):S529. Abstract M406. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richter A, Anton SE, Koch P, et al. The impact of reducing dose frequency on health outcomes. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2307–35. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80222-9. discussion 2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, et al. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–60. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:856–61. doi: 10.4065/80.7.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Data on File, PERSIST Clinical Study Protocol (Study ID MA 18160) F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller PD, McClung MR, Macovei L, et al. Monthly oral ibandronate therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 1-year results from the MOBILE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1315–22. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emkey R, Koltun W, Beusterien K, et al. Patient preference for once-monthly ibandronate vs. once-weekly alendronate in a randomized, open-label, cross-over trial: the Boniva Alendronate Trial in Osteoporosis (BALTO) Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1895–903. doi: 10.1185/030079905X74862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boccuzzi SJ, Folz SH, Kahler KH. Assessment of Adherence and Persistence with Daily and Weekly Dosing Regimens of Oral Bisphosphonates; Abstract presented at the 6th International Symposium on Osteoporosis; 2005; Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clowes JA, Peel NF, Eastell R. The impact of monitoring on adherence and persistence with antiresorptive treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1117–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B. Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2005;22:313–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02850081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xenical patient support service gets approval from Medicines Partnership. Pharm J. 2003;271:538. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sebaldt RJ, Shane LG, Pham BZ, et al. Impact on non-compliance and non-persistence with daily bisphosphonates on longer-term effectiveness outcomes in patients with osteoporosis treated in tertiary specialist care. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(Suppl. 1):S445. Abstract M423. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yood RA, Emani S, Reed JI, et al. Compliance with pharmacologic therapy for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:965–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finigan J, Bainbridge PR, Eastell R. Aherence to osteoporosis therapies. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(Suppl.):S48–9. Abstract P110. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, et al. The impact of poor compliance to osteoporosis treatment and risk of fractures in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(Suppl. 7):S78. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. Abstract P277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, et al. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:1003–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman S, Siris E, Abbott T, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy is associated with decreased nonvertebral osteoporotic fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(Suppl. 1):S286. Abstract SU417. [Google Scholar]