Abstract

The pneumococcal (Pn) conjugate vaccine includes seven different polysaccharides (PS) conjugated to CRM197. Utilizing antigen-processing cells and a CRM197-specific mouse T-cell hybridoma, we found that the serotype of conjugated PnPS dramatically affected antigen processing of CRM197. Unconjugated CRM197 and serotype conjugates 14 and 18C were processed more efficiently.

Antibodies (Ab) against capsular polysaccharides (PS) of Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pn) are protective against disease in animal models and in humans (15, 21). PS antigens, however, are T-independent type 2 antigens and generally do not induce immunological memory or a protective Ab response in infants less than 24 months of age (3, 5, 12, 15, 20, 21).

Immunization with PS conjugated to a carrier protein results in induction of protective levels of anti-PS Ab in infants as well as immunological memory (2, 21). The first effective conjugate vaccine used purified Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) PS linked to CRM197 (cross-reactive material), a nontoxic mutant diphtheria toxin (22), while other Hib vaccines use different carrier proteins. The use of these conjugate vaccines has resulted in the virtual eradication of Hib infections in the United States (2).

The currently licensed heptavalent PnPS conjugate vaccine is a combination vaccine containing seven purified serotypes of PnPS (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) individually conjugated to CRM197. This vaccine targets the Pn serotypes most frequently responsible for pediatric invasive disease in the United States (8, 9) and has been shown to have protective efficacy against invasive disease from homologous serotypes in children after four doses of vaccine (1, 17, 19).

Despite conjugation to the same carrier protein, the PnPS contained in the heptavalent conjugate vaccine elicit markedly different serotype-specific Ab titers in children and adults (1, 11, 17, 19). One potential explanation for the serotype-specific variation in immunogenicity of the components of the vaccine is that structurally different PnPS might affect antigen processing of the carrier protein, CRM197, yielding differences in carrier protein-induced T-cell help. We studied the effect of the serotype of PnPS conjugated to CRM197 on antigen processing of the carrier protein in cells from HLA-DR1-transgenic mice.

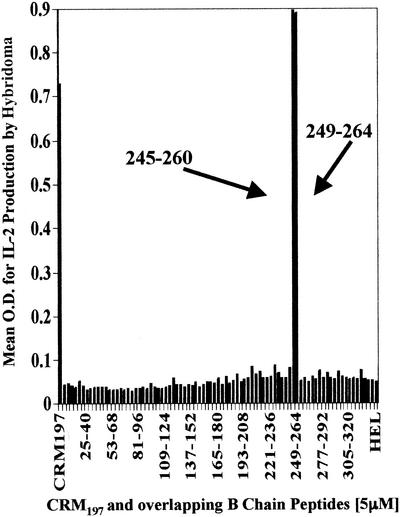

HLA-DR1-transgenic mice obtained from Merck Research Laboratories had a mixed background (C57BL/6, SJL/J, and B10.M) with a fixed H-2f locus (18). The Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University approved all of the animal protocols that were used. These mice were immunized with CRM197 and complete Freund's adjuvant. Lymph nodes were harvested, the cells were restimulated in vitro with CRM197, and restimulated T cells were fused with BW1100 CD4-transfected cells by using polyethylene glycol (16). Successfully fused cells were selected with hypoxanthine-aminopterin-thymidine. The hybridoma cells were screened for responses to CRM197 and HLA-DR1 restriction by using THP-1 cells, an HLA-DR1-expressing immortalized cell line, and then were cloned by limiting dilution. T-cell responses to antigen-processing cells (APC) presenting CRM197 peptides were measured as interleukin 2 (IL-2) production via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (23). The precise peptide to which the hybridoma responded was determined by using a series of overlapping peptides from the A and B chains of the CRM197 protein, adding them to splenocytes from the mice as APC, and measuring T-cell IL-2 production. The greatest response was observed with two adjacent peptides from the B fragment of CRM197 with the amino acid sequences PGKLDVNKSKTHISVN (CRM197 residues 245 to 260) and DVNKSKTHISVNGRKI (CRM197 residues 249 to 264). These peptides thus contain the epitope for this hybridoma (Fig. 1). No response was observed with peptides from the A fragment of CRM197 (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

The epitope for CRM197 T-cell hybridoma is on the B peptide of the diphtheria toxin. Splenocytes (4 × 105) and T-hybridoma cells (1 × 105) were incubated with 83 16-mer peptides at 5 μM concentrations. T-cell hybridomas secrete IL-2 in proportion to the amount of peptide-MHC complex presented. IL-2 production was measured by ELISA (mean optical density [O.D.]). Two adjacent B-chain peptides elicited the strongest response, as did the positive control of unconjugated intact CRM197. A-chain peptides (not shown), other B-chain peptides, and HEL did not stimulate the hybridoma.

In order to determine if the serotype of the PnPS affects processing of the carrier protein, multiple lots of PnPS-CRM197 conjugate types 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F (kindly supplied by Ronald Eby, Wyeth Vaccines, West Henrietta, N.Y.) were added to wells containing HLA-DR1-transgenic mouse splenocytes (1 × 105) or bone marrow macrophages (BMM; 1 × 105) in medium supplemented with recombinant mouse gamma interferon (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.), diluted according to the concentration of CRM197 (0 to 16 μg/ml). Hen egg lysozyme (HEL; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used as a negative control protein, and individual free PS from serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were also used as negative controls. T hybridoma cells (105) were then added to each well. The degree of peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation to the hybridoma was determined via IL-2 ELISA of the well supernatant after incubation.

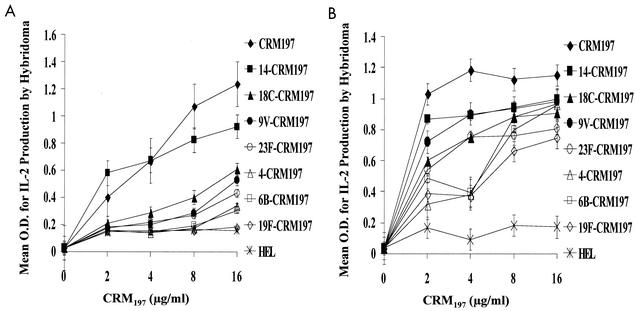

Splenocyte processing of the conjugates containing different serotypes of PnPS linked to CRM197 yielded markedly different presentation of the CRM197 peptide to the T-cell hybridoma (Fig. 2A). Unconjugated carrier protein was better recognized by the hybridoma than any of the PnPS-CRM197 conjugates, while carrier protein from serotype 14 and 18C conjugates was more efficiently processed and presented than that from the 9V, 4, and 23F conjugates. Carrier proteins from the serotype 19F and 6B conjugates were presented least efficiently, with recognition by the hybridoma being only slightly better than that demonstrated by incubation with HEL (Fig. 2A). None of the control unconjugated PnPS serotypes elicited IL-2 production, and addition of free PS to CRM197 did not affect antigen processing (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when BMM from HLA-DR1-transgenic mice were used as APC. As observed in the splenocyte experiments, unconjugated CRM197 was processed most efficiently, and CRM197 conjugated to serotypes 14 and 18C was presented more efficiently than that conjugated to serotypes 4 and 6B (Fig. 2B). Differences in protein content of the individual PnPS serotype-CRM197 conjugates did not explain the different responses, since the components were diluted to contain identical quantities of CRM197 (the protein content of the conjugates was confirmed by bicinchoninic acid protein assay). Similar results were also obtained with different lots of vaccine.

FIG. 2.

(A) Serotype of the PnPS attached to the CRM197 carrier protein has a dramatic effect on the processing of CRM197 by splenocytes from HLA-DR1-transgenic mice. CRM197-specific T-hybridoma cells (1 × 105) were incubated with splenocytes (4 × 105) and various concentrations of CRM197, individual serotype PnPS-CRM197 conjugates contained within the heptavalent vaccine (diluted according to CRM197 concentration), or HEL. Antigen presentation, as determined by IL-2 production by the T-cell hybridoma, was measured by ELISA. Intact CRM197 elicited the greatest response, while serotype 14 and 18C CRM197 conjugates elicited greater responses than 19F and 6B CRM197 conjugates. (B) Serotype of the PnPS attached to the CRM197 carrier protein has a dramatic effect on the processing of CRM197 by BMM from the HLA-DR1-transgenic mouse. BMM (1.5 × 105) and T-hybridoma cells (1 × 105) were incubated with unconjugated CRM197, the seven individual serotypes of the PnPS-CRM197 conjugates contained within the heptavalent vaccine (diluted according to CRM197 concentration), and HEL. IL-2 production by the T-cell hybridoma, as an indicator of stimulation by CRM197 peptide-MHC on the surface of the APC, was measured by ELISA. Intact CRM197 elicited the greatest T-cell response, and serotype 14 and 18C CRM197 conjugates elicited greater responses than conjugates of 6B and 4 at low concentrations of CRM197. As the amount of CRM197 added to the APC increased, the difference between serotypes diminished, suggesting that the BMM processed CRM197 with higher efficiency than splenocytes.

The proposed mechanism for the enhanced immunogenicity of PS-protein glycoconjugate vaccines compared to that of pure PS involves recognition and internalization of the glycoconjugate by a PS-specific B cell, endosomal proteolysis of the carrier protein, noncovalent association of peptide fragments with class II MHC molecules, and presentation of this complex at the cell surface to a CD4+ T cell with receptor specificity for the carrier protein and the MHC molecule (4, 6, 23). The association of carrier-derived, MHC II-bound peptide with the T-cell receptor activates the T cell to secrete a variety of cytokines along with CD40/CD40L interactions that presumably stimulate the PS-specific B cell to proliferate, secrete Ab, undergo isotype switching, and differentiate into memory cells.

PS do not bind to class II MHC molecules and, therefore, do not directly activate T cells (7, 10). However, Ishioka et al. observed that glycosylation of a known peptide T-cell epitope affected the MHC binding and T-cell recognition of the peptide depending on the location of the carbohydrate moieties relative to the residues of the core MHC-binding regions on the peptide (10). When carbohydrate was located in the core MHC-binding region, either T-cell recognition was abolished or the antigenic determinant recognized by the T cell was altered. It seems probable that the structure of the carbohydrate conjugated to CRM197 influences the variety of epitopes produced from carrier protein if proteolysis or MHC binding is affected. We also previously demonstrated that T cells from mouse lymph nodes generated by immunization with CRM197 alone, 6B-CRM197, 19F-CRM197, or 23F-CRM197 recognized different peptide epitopes on the carrier protein when screened with the same 16-mer peptides used to map our T-cell hybridoma (14). This finding again suggests that the serotype of the PS had influence over the T-cell epitopes produced by the APC. Since the linkage sites in the PnPS conjugates between PS and protein are random, individual PnPS serotypes are not conjugated to the same part of the CRM197 molecule. Thus, the observed differences in the antigen processing of the various conjugates by APC may relate to the proximity of the PS linkage to the MHC-binding region of the carrier protein (10).

We demonstrated substantial differences in the presentation of CRM197 to T-hybridoma cells by APC after processing of different serotypes of PnPS-CRM197 conjugates. Other studies have shown that the individual components of the PnPS conjugate vaccine elicit different patterns of cytokine responses from carrier-specific T cells. Mice immunized with type 14-CRM197 and 19F-CRM197 PnPS vaccines produced markedly different cytokine responses in splenocytes upon restimulation with the conjugates (13). These cytokine profiles were associated with different immunoglobulin G subclass Ab responses against the PS.

The observed differences in the efficiency of CRM197 processing based on the serotype of the attached PnPS would not likely explain the variable serotype specific anti-PS Ab responses noted in both mice and humans. Since all seven serotypes of PnPS conjugated to CRM197 in the multivalent vaccine are administered simultaneously, such differences in efficiency of antigen processing may be irrelevant in immunized humans. In addition, we have recently reported that CD4+ T cells taken from adult volunteers immunized with the heptavalent PnPs-CRM197 conjugate vaccine demonstrate uniformly vigorous proliferation ex vivo when stimulated with any of the individual serotypes of PnPS-CRM197 contained in the vaccine, even though some serotypes were mediocre immunogens (11). These data suggested that B-cell repertoire, not lack of T-cell help, might also be an important cause of the serotype-specific differences in the immunogenicity of this heptavalent vaccine in adults. Differences in the quality or quantity of T-cell help in infants immunized with conjugate vaccines might be a possible explanation for the differences in isotype-specific response to conjugate vaccine. A limitation of our study was a lack of access to neonatal HLA-DR1-transgenic mice to explore the effect of PS-protein conjugation on the processing of the carrier protein by immature APCs.

Future studies with animal and human subjects should be performed with these glycoconjugates to determine if differences in the haplotype of MHC molecules affect antigen processing and, ultimately, immunogenicity. Since T cells from the HLA-DR1-transgenic mouse will respond to APC from HLA-DR1+ humans (approximately 12% of the population), future experiments can also explore the kinetics and character of processing of CRM197 when conjugated to various PnPS serotypes by human APCs. A similar approach could be used with T-cell hybridomas restricted to other human HLA-DR alleles.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ronald Eby of Wyeth Vaccines for providing the CRM197 as well as the individual PnPS-CRM197 conjugate vaccines.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 32596 (J.R.S.), AI 46667 (J.R.S.), AI 01581 (D.H.C.), AI 35726 (C.V.H.), and AI 47255 (C.V.H.).

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Black, S., H. Shinefield, B. Fireman, E. Lewis, P. Ray, J. R. Hansen, L. Elvin, K. M. Ensor, J. Hackell, G. Siber, F. Malinoski, D. Madore, I. Chang, R. Kohberger, W. Watson, R. Austrian, K. Edwards, et al. 2000. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, S. B., H. R. Shinefield, B. Fireman, R. Hiatt, M. Polen, E. Vittinghoff, et al. 1991. Efficacy in infancy of oligosaccharide conjugate Haemophilus influenzae type b (HbOC) vaccine in a United States population of 61,080 children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan, M. J., A. J. Ammann, D. W. Wara, V. M. Howie, L. Schultz, N. Doyle, and M. Kaplan. 1978. Pneumococcal polysaccharide immunization in infants and children. Pediatrics 62:721-727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cresswell, P. 1994. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:259-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas, R. M., J. C. Paton, S. J. Duncan, and D. J. Hansman. 1983. Antibody response to pneumococcal vaccination in children younger than five years of age. J. Infect. Dis. 148:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germain, R. N. 1994. MHC-dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for T lymphocyte activation. Cell 76:287-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding, C. V., R. W. Roof, P. M. Allen, and E. R. Unanue. 1991. Effects of pH and polysaccharides on peptide binding to class II major histocompatibility complex molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2740-2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hausdorff, W. P., J. Bryant, C. Kloek, P. R. Paradiso, and G. R. Siber. 2000. The contribution of specific pneumococcal serogroups to different disease manifestations: implications for conjugate vaccine formulation and use, part II. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:122-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausdorff, W. P., J. Bryant, P. R. Paradiso, and G. R. Siber. 2000. Which pneumococcal serogroups cause the most invasive disease: implications for conjugate vaccine formulation and use, part I. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:100-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishioka, G. Y., A. G. Lamont, D. Thomson, N. Bulbow, F. C. Gaeta, A. Sette, and H. M. Grey. 1992. MHC interaction and T cell recognition of carbohydrates and glycopeptides. J. Immunol. 148:2446-2451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamboj, K., H. L. Kirchner, R. Kimmel, N. Greenspan, and J. R. Schreiber. 2003. Significant variation in serotype-specific immunogenicity of the seven-valent Streptococcus pneumoniae-CRM197 conjugate vaccine occurs despite vigorous T cell help induced by the carrier protein. J. Infect. Dis. 187:1629-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayhty, H., V. Karanko, H. Peltola, and P. H. Makela. 1984. Serum antibodies after vaccination with Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide and responses to reimmunization: no evidence of immunologic tolerance or memory. Pediatrics 74:857-865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mawas, F., I. M. Feavers, and M. J. Corbel. 2000. Serotype of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide can modify the Th1/Th2 cytokine profile and IgG subclass response to pneumococcal-CRM(197) conjugate vaccines in a murine model. Vaccine 19:1159-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCool, T. L., C. V. Harding, N. S. Greenspan, and J. R. Schreiber. 1999. B- and T-cell immune responses to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines: divergence between carrier- and polysaccharide-specific immunogenicity. Infect. Immun. 67:4862-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mond, J. J., A. Lees, and C. M. Snapper. 1995. T cell-independent antigens type 2. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:655-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noss, E. H., C. V. Harding, and W. H. Boom. 2000. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits MHC class II antigen processing in murine bone marrow macrophages. Cell. Immunol. 201:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rennels, M. B., K. M. Edwards, H. L. Keyserling, K. S. Reisinger, D. A. Hogerman, D. V. Madore, I. Chang, P. R. Paradiso, F. J. Malinoski, and A. Kimura. 1998. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine conjugated to CRM197 in United States infants. Pediatrics 101:604-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosloniec, E. F., D. D. Brand, L. K. Myers, K. B. Whittington, M. Gumanovskaya, D. M. Zaller, A. Woods, D. M. Altmann, J. M. Stuart, and A. H. Kang. 1997. An HLA-DR1 transgene confers susceptibility to collagen-induced arthritis elicited with human type II collagen. J. Exp. Med. 185:1113-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinefield, H. R., S. Black, P. Ray, I. Chang, N. Lewis, B. Fireman, J. Hackell, P. R. Paradiso, G. Siber, R. Kohberger, D. V. Madore, F. J. Malinowski, A. Kimura, C. Le, I. Landaw, J. Aguilar, and J. Hansen. 1999. Safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal CRM197 conjugate vaccine in infants and toddlers. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:757-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, D. H., G. Peter, D. L. Ingram, A. L. Harding, and P. Anderson. 1973. Responses of children immunized with the capsular polysaccharide of Hemophilus influenzae, type b. Pediatrics 52:637-644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein, K. E. 1992. Thymus-independent and thymus-dependent responses to polysaccharide antigens. J. Infect. Dis. 165(Suppl. 1):S49-S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida, T., A. M. Pappenheimer, Jr., and A. A. Harper. 1972. Reconstitution of diphtheria toxin from two nontoxic cross-reacting mutant proteins. Science 175:901-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner, D. K., J. York-Jolley, T. R. Malek, J. A. Berzofsky, and D. L. Nelson. 1986. Antigen-specific murine T cell clones produce soluble interleukin 2 receptor on stimulation with specific antigens. J. Immunol. 137:592-596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]