Abstract

Protection against the pathogenic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum requires Th1 cytokines. Since interleukin-4 (IL-4) can inhibit both Th1 cytokine production and activity, we examined the effects of overproduction of IL-4 in the lung on the course of pulmonary histoplasmosis. IL-4 lung transgenic mice manifested a higher fungal burden in their lungs, but not spleens, compared to wild-type infected controls. Despite the higher burden, the transgenic animals were ultimately capable of controlling infection. The adverse effects of IL-4 on H. capsulatum elimination were not observed during the early phase of infection (days 1 to 3) but were maximal at day 7 postinfection, prior to the induction of cell-mediated immunity. Analysis of total body and lung cytokine levels revealed that gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha production were not inhibited in the presence of excess IL-4. Our results with transgenic mice were supported by additional in vivo studies in which allergen induction of pulmonary IL-4 was associated with delayed clearance of H. capsulatum yeast and increased fungal burden. These findings demonstrate that excess production of endogenous IL-4 modulates protective immunity to H. capsulatum by delaying clearance of the organism but does not prevent the generation of a Th1 response that ultimately controls infection.

Infections with the pathogenic fungus, Histoplasma capsulatum, are common in North and South America reaching an endemic status in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys. Although macrophages are the primary effector cells in H. capsulatum infection, maturation of cell-mediated immunity is critical for host protection and, ultimately, resolution of histoplasmosis (7, 23).

Host protection against H. capsulatum requires development of a Th1 cytokine immune response (1, 2, 7, 36). Murine models of histoplasmosis have demonstrated that gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are critical cytokines involved in the protective immune response to H. capsulatum yeast. Mice deficient in these cytokines (2, 4, 35) or mice treated with neutralizing antibodies to these cytokines (1, 8, 34-36) exhibit defects in their responses to either primary or secondary infections or both. These defects include, but are not limited to, decreased macrophage antifungal activity and impaired clearance of yeast from visceral organs. The result often is uncontrolled infection (1-3, 8, 34-36). Although these cytokines may express distinct and/or overlapping roles in the immune response to H. capsulatum yeast, it is evident that protective immunity in the host is skewed toward a type I phenotype.

IL-4 is a Th2 cytokine that has pleiotropic effects on the immune system. IL-4 stimulates naive CD4+ T cells to differentiate into Th2 cytokine-secreting cells (6, 18, 24, 25, 31); promotes antigen presentation by B cells and dendritic cells (29); promotes B-cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation (5, 9, 29); and is a chemoattractant for neutrophils and eosinophils (19, 22, 38). In addition, IL-4 alters inflammatory cell activity to an allergic response, inhibits cytotoxic activity, suppresses inflammatory responses associated with type I cytokine production (IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) and inhibits killing of intracellular or small extracellular organisms (10, 14). It is required for protection against some ectoparasites (20) and many gastrointestinal worm infections (11, 12, 32, 33).

Indirect evidence suggests that endogenous IL-4 can exacerbate pulmonary and systemic histoplasmosis and thus is inimical to host defenses against H. capsulatum (1, 3, 8, 37). The negative effects of IL-4 on H. capsulatum infection have been apparent only in mice that manifest decreased levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, or GM-CSF or naive mice infected with a large intravenous inoculum. In the present study, we sought to determine whether overproduction of IL-4, specifically in the lung, would blunt the ability of mice that did not possess preexisting deficiency in IFN-γ, TNF-α, or GM-CSF to clear H. capsulatum. The results indicate that excess IL-4 causes increased fungal burden in lungs of transgenic animals without suppressing IFN-γ and TNF-α levels; however, infection is ultimately controlled despite the increased levels of IL-4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

IL-4 lung transgenic mice (CBA background) were kindly provided by Jeffrey Whitsett (27) and were bred and backcrossed onto a BALB/c background at the Cincinnati Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) Generation 7 BALB/c IL-4 lung transgenic mice (IL-4 LTgn) and wild-type littermates were age and sex matched in individual experiments. IL-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Rα) and IL-4 knockout (KO) mice (24), on a BALB/c background, were bred at the Cincinnati VAMC, along with BALB/c wild-type mice. Both were age and sex matched in each experiment.

Preparation of H. capsulatum and infection of mice.

H. capsulatum yeast (strain G217B) was prepared as described previously (2). The strain is a prototypical virulent strain of this fungus. To produce infection in naive mice, animals were infected intranasally (i.n.) with 2 × 106 or with 2 × 107 yeast in a 25- to 50-μl volume of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS).

Preparation of APF.

Ascaris pseudocoelomic fluid (APF) was a gift of Joseph Urban, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, Md. Adult male and female worms were freshly recovered from the intestines of pigs and kept at room temperature in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution in transit to the laboratory, where they were washed several times in PBS. The pseudocoelom was cut with scissors, and the fluid was drained into a collection flask. The fluid was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored frozen at −70°C until used.

Immunization.

Wild-type mice were anesthetized with diethyl ether (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) inhalation and inoculated i.n. with 20 μl of saline or with APF three times per week for 2 weeks. Immunized mice were then infected i.n. with 2 × 106 yeast as described above and monitored for 7 days. APF immunization continued after H. capsulatum inoculation for 1 week at three times per week until the animals were sacrificed.

Organ culture for H. capsulatum.

Lungs and spleens were homogenized in HBSS and serially diluted and dispensed (100 μl) onto plates containing brain heart infusion agar (2% agar [wt/vol]) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) defibrinated sheep erythrocytes, 1% glucose, and 0.01% (wt/vol) cysteine hydrochloride. Plates were incubated at 30°C, and CFU were counted 7 to 10 days later. Data are expressed as CFU per organ.

IVCCA.

The in vivo cytokine capture assay (IVCCA) was used to monitor in vivo production of IL-4, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10. This assay allows cytokines to accumulate by capturing them in vivo at the site of production with neutralizing immunoglobulin G (IgG) monoclonal antibodies (MAb) that inhibit their excretion, utilization, and catabolism (13). Cytokine anti-cytokine MAb complexes circulate via the lymph to serum, where they can be detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This technique increases the ability to detect IL-4 in serum by >100-fold and is specific. To capture secreted IL-4, mice were injected intravenously with 10 μg of a biotin-conjugated neutralizing rat MAb to IL-4 (BVD4-1D11). Mice were bled 24 h later, and the levels of IL-4-biotin-anti-IL-4 complexes in serum were determined by ELISA by using microtiter plates coated with a rat MAb to IL-4 (BVD6-24G2.3), an MAb that recognizes an IL-4 epitope distinct from that recognized by BVD4-1D11. IVCCA for IFN-γ, IL-10, and TNF-α was performed similarly by injecting mice with 10 μg of biotin-labeled MAb obtained from the cell lines R46-A2 (IFN-γ), JES5-16E3 (IL-10; Pharmingen, La Jolla, Calif.), and TN3 (TNF-α; Pharmingen) and then coating microtiter plates with MAb from cell lines AN18 (IFN-γ), JES5-2AS (IL-10, Pharmingen), or rabbit anti-TNF polyclonal antibody (Pharmingen), respectively.

Lung cytokine measurement.

Lungs were removed from mice on sequential days after yeast inoculation, homogenized in 2 ml of HBSS, centrifuged at 1500 × g, and stored at −70°C until assayed. Commercially available ELISA kits (Pierce-Endogen, Rockford, Ill.) were used to measure IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and TNF-α.

Statistics.

Differences in survival were analyzed by log-rank test, and differences in cytokine production and fungal burden in organs were analyzed by uisng the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

RESULTS

Course of histoplasmosis in mice that overexpress IL-4 in the lung and cytokine levels between transgenic and control mice.

Mice that express an IL-4 transgene under the control of the CC-10 pulmonary Clara cell-specific promoter,IL-4 LTgn mice, and wild-type controls (BALB/c) were infected i.n. with a 2 × 106 yeast, and the numbers of CFU in the lungs and spleens were determined. Since the spleen is a site of dissemination for this fungus, we analyzed the effect of IL-4 overexpression on both visceral and lymphoid organs. Mice were sacrificed on day 1, 3, 7, 14, or 30 after infection, and their lungs and spleens were cultured for H. capsulatum (Fig. 1). No differences in fungal recovery between IL-4 Tgn and wild-type mice were observed on day 1 or 3 postinfection. The lungs of IL-4 LTgn mice contained between 0.5 and 1.0 log10 (P < 0.01, day 7; P < 0.05; days 14 and 30) more CFU than lungs from infected controls. The burden of H. capsulatum in spleens was similar (P > 0.05) to the control on days 1, 3, 14, and 30 but was increased on day 7 (P ≤ 0.05), the day at which fungal burden peaked in the lung (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Fungal burden in the lungs and spleens of naive IL-4 LTgn mice and wild-type controls. IL-4 LTgn (n = 5) and BALB/c wild-type control (n = 5) mice were infected i.n. with 2 × 106 yeast. On day 1, 3, 7, 14, or 30 days after infection, mice were sacrificed, and their lungs and spleens were cultured for H. capsulatum CFU. The data are the mean ± the SEM. ✽, P < 0.05; #, P < 0.001.

Total body and lung cytokine levels in IL-4 LTgn and wild-type mice infected with H. capsulatum.

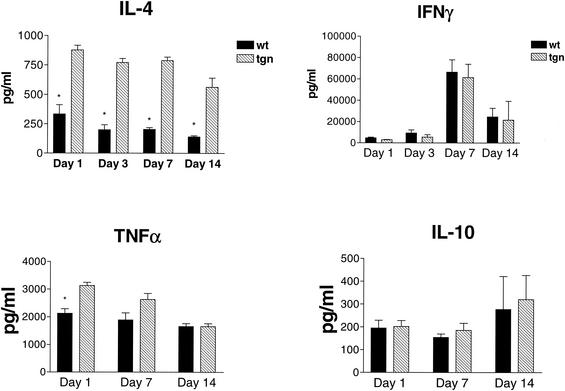

In parallel, we measured the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 in both the whole body and the lungs of mice. Total-body cytokine production was measured by IVCCA at 1, 3, 7, or 14 days after inoculation, whereas lung cytokine levels were measured 1, 3, 7, 14, or 30 days after inoculation. Total-body IL-4 production was significantly higher in transgenic animals at each day (P < 0.05), but there was no difference in IFN-γ or IL-10 production. TNF-α generation was higher in transgenic mice at each time point analyzed, but this difference was only significant at day 1 prior to infection (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Serum cytokine profiles of IL-4 LTgn and wild-type-infected mice. Cytokine levels in serum were measured by IVCCA at 1, 3, 7, or 14 days after inoculation. Mice were injected intravenously with biotin-labeled antibodies to the cytokines shown on day 0, 2, 6, or 13 after infection and bled 24 h later. Serum was prepared and cytokine levels were measured by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. The data are the mean ± the SEM of five animals per group. ✽, P < 0.05.

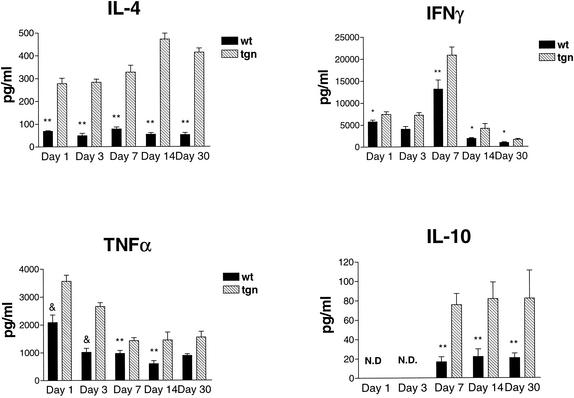

To quantify the levels of cytokines in lungs, we assayed lung homogenates by ELISA. The levels of TNF-α (P < 0.01, days 7, 14, and 30; P ≤ 0.005, days 1 and 3), IFN-γ (P ≤ 0.01, days 3 and 7; P ≤ 0.05, days 1, 14, and 30), and IL-4 (P < 0.01, all days) in lung extracts were significantly higher in IL-4 LTgn mice than in wild-type mice on each day postinfection (Fig. 3). The level of IL-10 also was increased and significantly higher than in controls each day (P < 0.01). Although IFN-γ levels were elevated in the IL-4 LTgn animals, it decreased in both groups over time as the animals began to clear the infection (Fig. 3). Thus, the presence of IL-4 impaired host clearance most dramatically on day 7 and was not associated with decreases in either IFN-γ or TNF-α, two cytokines that are critically important in host resistance to this fungus.

FIG. 3.

Lung cytokine levels in Tgn and wild-type mice infected with H. capsulatum. Cytokine levels in the lungs were quantified by ELISA of tissue homogenates on day 1, 3, 7, 14, or 30 after primary infection. The data represent the mean ± the SEM (n = 5). ✽ P < 0.05; ✽✽, P < 0.01; &, P < 0.005.

Course of histoplasmosis in mice administered APF.

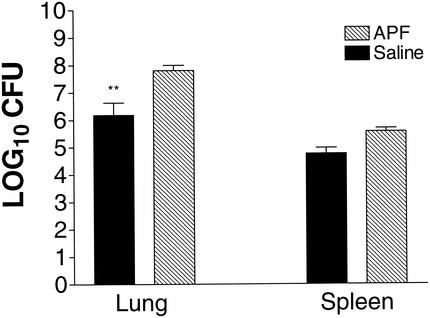

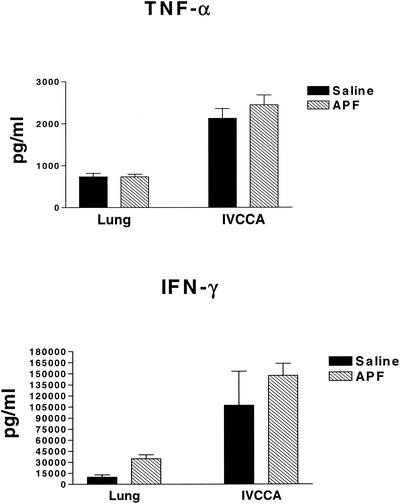

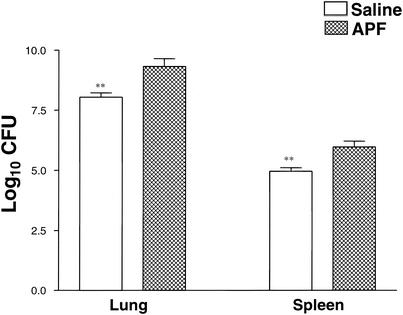

Another approach to studying the relationship between IL-4 and H. capsulatum is to determine whether allergen induction of increased IL-4 production impairs immunity. Wild-type mice (n = 5) were inoculated i.n. three times per week for 2 weeks with the allergen APF, which induces a pulmonary IL-4 response that can be measured by IVCCA. The mean (± the standard error of the mean [SEM]) level of total body IL-4 in wild-type BALB/c mice given saline was 63.5 ± 14.5 pg/ml, and this value was significantly lower (P < 0.01) than the level in mice given APF (481.0 ± 161.4 pg/ml). After exposure to saline or APF, mice were inoculated with 2 × 106 yeast and sacrificed on day 7. APF-immunized wild-type mice manifested elevated CFU in lungs and spleens (P ≤ 0.01) compared to mice that were inoculated with saline (Fig. 4). Serum and lung IFN-γ and TNF-α production were not inhibited by APF-induced IL-4 production (Fig. 5). In a separate experiment, APF immunization still had a significant (P ≤ 0.01) inhibitory effect on host protection in IL-4-deficient mice (Fig. 6). Thus, the inhibitory effect of allergen immunization on clearance or H. capsulatum is at least partially independent of the effects of IL-4.

FIG. 4.

Fungal burden in APF-immunized animals. Groups of mice (n = 5) were immunized three times per week for 2 weeks with either APF allergen or saline. After pretreatment, mice were inoculated with yeast, treated an additional week with either APF or saline, and then sacrificed on day 7. Lungs and spleens were assayed for H. capsulatum CFU. The data represent the mean ± the SEM. ✽✽, P < 0.01.

FIG. 5.

Cytokine profiles of APF-immunized, H. capsulatum-infected animals. Cytokine profiles in serum and lungs of mice immunized i.n. with APF and inoculated with yeast are shown. The lungs of mice were assayed for levels of cytokine by ELISA of tissue homogenates (n = 5), and levels in serum were measured by IVCCA on day 7 of infection prior to sacrifice. The data represent the mean ± the SEM.

FIG. 6.

Fungal burden in IL-4-deficient APF-immunized mice. IL-4-deficient (n = 5) and BALB/c wild-type (n = 5) mice were treated three times per week for 2 weeks with either APF or saline control and then inoculated with 2 × 106 H. capsulatum yeast. The APF or saline treatment was continued for 1 week at three times per week after H. capsulatum infection. Animals were sacrificed on day 7, and the lungs and spleens were assayed for H. capsulatum CFU. The data represent the mean ± the SEM. ✽✽, P < 0.01.

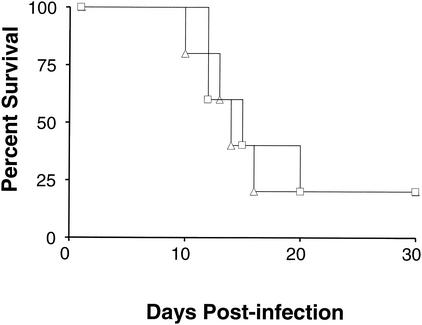

Survival of IL-4Rα KO mice given a higher inoculum of H. capsulatum yeast.

Concomitantly, we sought to determine whether total suppression of IL-4 signaling would protect against 2 × 106 yeast. Mice deficient in the IL-4Rα chain lack the ability to respond to both IL-4 and IL-13 (15, 28, 38, 39). Mice deficient in the IL-4Rα and wild-type controls were inoculated i.n. with 2 × 107 yeast. Both mouse strains were noted to demonstrate decreased mobility, ruffled fur, and huddling. These symptoms progressed until the animals became moribund (Fig. 7). No differences in survival were observed, even though higher IFN-γ levels (P < 0.01) developed in the serum of IL-4Rα-deficient mice (Fig. 8). Thus, our results suggest that overexpression of IL-4 can have a negative and even lethal effect in H. capsulatum infections, and yet the absence of IL-4 does not protect against a normally lethal inoculum.

FIG. 7.

Survival curve of IL-4Rα-deficient and wild-type mice infected with H. capsulatum. IL-4Rα-deficient (▵; n = 5) and BALB/c wild-type control (□, n = 5) mice were infected with doses of 2 × 107 H. capsulatum yeasts and monitored for survival for 30 days.

FIG. 8.

Total body levels of IFN-γ levels in mice infected with a higher dose of H. capsulatum yeasts. IL-4Rα-deficient mice (n = 5) and wild-type control mice (n = 5) were infected with 2 × 107 H. capsulatum yeasts and monitored for survival as depicted in Fig. 8. On day 6 postinfection, mice were injected intravenously with neutralizing MAb complexes and bled 24 h later for IVCCA measurements. Serum was prepared, and IFN-γ levels in serum were measured by ELISA. ✽✽, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that elevated levels of IL-4 impair host resistance to H. capsulatum. The higher levels of IL-4 were accompanied by increases in yeast numbers and a delayed pulmonary clearance in response to a lower inoculum. Analysis of cytokine levels in the IL-4 LTgn mice revealed increased levels of IL-4 and IL-10 in the total body and in the lungs. IFN-γ and TNF-α levels were similar to those in controls in the total body but were significantly elevated in the lungs. The higher levels of cytokines known to impair host resistance to this fungus (IL-4 and IL-10) were increased, whereas those critically involved in host control (IFN-γ and TNF-α) were either increased or unaltered depending on where they were measured. This finding establishes that overexpression of IL-4 can perturb protective immunity to this fungus even when lung levels of protective cytokines are elevated.

In the absence of exposure to foreign antigen or pathogens, the IL-4 LTgn mice develop numerous alterations in the pulmonary parenchyma. There is a progressive rise in the number of inflammatory cells from both myeloid and lymphoid lineage. Among myeloid cells, there is a marked increase in several populations including neutrophils, macrophages, and eosinophils. In addition, there is enhanced production of surfactant proteins A, B, and C and mucous. Eosinophilic crystals develop within the parenchyma (27). Such findings resemble those found in the lung of asthmatics or those with chronic inflammation caused by allergens.

Despite the preexisting increase in the number of inflammatory cells, the IL-4 LTgn mice were unable to clear H. capsulatum as rapidly or more rapidly than wild-type controls. Both neutrophils and macrophages are critically important phagocytes in host resistance to H. capsulatum (23, 35). One explanation for the defect in host defenses that was apparent in the IL-4 LTgn mice is that the populations of inflammatory cells do not function optimally to phagocytize and then destroy yeast. Such dysfunction would have to be pathogen-specific rather than global since these same mice exhibit an accelerated clearance of the bacterium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Intratracheal injection of this P. aeruginosa into wild-type and IL-4 LTgn mice resulted in a more rapid elimination in the latter strain (16). In support of an ameliorative role for IL-4, administration of IL-4 i.n. to mice prior to intratracheal injection of P. aeruginosa resulted in enhanced clearance (16). Thus, the inimical effects of IL-4 in histoplasmosis do not appear to be caused by marked decrements in cytokines known to be protective in murine histoplasmosis (IFN-γ and TNF-α) or by a global alteration in phagocyte function.

Although the exact mechanism of IL-4 action in this system remains to be elucidated, a possible explanation for the adverse effects of IL-4 on organism clearance could be that IL-4 may inhibit some of the protective effects of these cytokines. For example, IL-4 may inhibit macrophage-dendritic cell anti-Histoplasma function by decreasing iNOS production or stimulating production of other cytokines that inhibit protection (26). Future experiments will examine the role of IL-4 on protective cellular functions.

Although the numbers of organisms in the lungs of the IL-4 LTgn were higher, this did not result in a more pronounced dissemination of yeast to the spleen. That is, the higher burden in the lung did not cause a higher burden in the spleen. This finding probably reflects the restriction of elevated IL-4 levels to the lungs in IL-4 LTgn mice. In addition, there may be differences in the regulation of immunity by IL-4 in the lungs versus the spleen, as has been observed in other systems (3). We previously reported that the balance between IL-4 and IFN-γ was a pivotal determinant in host control of histoplasmosis (1). In this regard, administration of MAb to IL-12 caused a sharp reduction in IFN-γ levels in the lungs of mice but did not alter IL-4. These mice, nevertheless, succumbed to infection. The inimical effect of a lack of Th1 cytokines was reversed by MAb to IL-4, suggesting that a restoration of balance between these two cytokines is important for host control. Likewise, the elevation of IL-4 induced by a transgene or by the allergen APF shifted the balance between IL-4 and IFN-γ without necessarily altering the absolute levels of IFN-γ.

Impaired host resistance in mice with increased levels of IL-4 was coincident with the onset of the cell-mediated immune response to pulmonary challenge with H. capsulatum. Overexpression of IL-4 did not alter the handling of infection during the acute stages (<7 days) of infection. These results indicate that the innate immune protective response functions adequately during the acute phase of infection. Moreover, the higher levels of IL-4 in lungs did not lead to a demise of the animals given a sublethal inoculum. One likely explanation for this finding was that the levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in the lungs were significantly elevated. These two cytokines are protective, and the elevated levels may have counteracted the inimical effects of IL-4 (1-3).

Surprisingly, our studies revealed that the lack of IL-4 signaling is not protective against a pulmonary challenge with H. capsulatum. IL-4Rα KO mice failed to control a high-dose infection, and the same proportion of KO mice succumbed as quickly as did the wild-type mice. Others also have found that the inability to generate a Th2 response through IL-4 does not augment host resistance to an intracellular pathogen. IL-4Rα KO mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis are no more resistant that wild-type mice (17). In fact, the lack of IL-4 signal transduction does cause the development of large, nonnecrotic, granulomas in response to M. tuberculosis, as well as an increased lung CFU (30). Thus, although an exuberant Th2 response may be harmful, the lack of a Th2 response does not appear to improve host immunity to H. capsulatum or M. tuberculosis. This may reflect a contribution of IL-4 to the optimal expression of Th1 immunity in some model systems (6). Impairment of Th1 immunity, in the absence of IL-4, may balance the suppressive effects of IL-4 on host protection. Such an impairment would have to be selective, however, because IFN-γ levels were higher in H. capsulatum-infected IL-4Rα KO mice than in wild-type animals.

In our study, we demonstrated that overexpression of IL-4 in the lungs of animals resulted in an impaired Th1 immune response. The defect is unlikely to be caused by diminished levels of IFN-γ or TNF-α or by a global alteration in phagocyte killing function. Utilizing different systems to generate elevated IL-4 levels (IL-4 LTgn and allergen induced) suggests that disorders characterized by overproduction of IL-4 (such as asthma) may increase susceptibility to pulmonary fungal infection. Even the inflammation induced by an allergen, in the absence of IL-4 effect, may suppress host resistance to H. capsulatum, as suggested by our results with APF-inoculated IL-4-deficient mice. This suppressive effect may result from the production of IL-13 that shares many effects with IL-4 (10, 12). In conjunction with other reports on the protective effects of IL-4, these results, if applicable to humans, put forth the possibility that on a practical level differential diagnosis of pulmonary infection in atopic asthmatic individuals should be approached somewhat differently than the differential diagnosis of pulmonary infection in individuals who do not have atopic asthma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a REAP award from the Veterans Affairs Administration (G.S.D. and F.D.F.), Merit Reviews to G.S.D and F.D.F., and grants AI-34361 and AI-42747 (G.S.D.) and AI-35587 (F.D.F.).

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Allendoerfer, R., G. P. Boivin, and G. S. Deepe, Jr. 1997. Modulation of immune responses in murine pulmonary histoplasmosis. J. Infect. Dis. 175:905-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allendoerfer, R., and G. S. Deepe, Jr. 1997. Intrapulmonary response to Histoplasma capsulatum in gamma interferon knockout mice. Infect. Immun. 65:2564-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allendoerfer, R., and G. S. Deepe, Jr. 1998. Blockade of endogenous TNF-α exacerbates primary and secondary pulmonary histoplasmosis by differential mechanisms. J. Immunol. 160:6072-6082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allendoerfer, R., and G. S. Deepe, Jr. 2000. Regulation of infection with Histoplasma capsulatum by TNFR1 and -2. J. Immunol. 165:2567-2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banchereau, J., F. Bazan, D. Blanchard, F. Briere, J. P. Galizzi, C. van Kooten, Y. J. Liu, F. Rousset, and S. Saeland. 1994. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:881-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biedermann, T., S. Zimmermann, H. Himmelrich, A. Gumy, O. Egeter, A. K. Sakrauski, I. Seegmuller, H. Voigt, P. Launois, A. D. Levine, H. Wagner, K. Heeg, J. A. Louis, and M. Rocken. 2001. IL-4 instructs TH1 responses and resistance to Leishmania major in susceptible BALB/c mice. Nat. Immunol. 2:1054-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cain, J. A., and G. S. Deepe, Jr. 2000. Evolution of the primary immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum in murine lung. Infect. Immun. 66:1473-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deepe, G. S., Jr., R. Gibbons, and E. Woodward. 1999. Neutralization of endogenous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor subverts the protective immune response to Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Immunol. 163:4985-4993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Defrance, T., J. P. Aubry, F. Rousset, B. Vanbervliet, J. Y. Bonnefoy, N. Arai, Y. Takebe, T. Yokoto, F. Lee, K. Arai, et al. 1987. Human recombinant interleukin 4 induces Fc epsilon receptors (CD23) on normal human B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 165:1459-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Waal Malefyt, R., C. G. Figdor, and J. E. de Vries. 1993. Effect of interleukin 4 on monocyte functions: comparison to interleukin 13. Res. Immunol. 144:629-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Else, K. J., F. D. Finkelman, C. R. Maliszewski, and R. K. Grencis. 1994. Cytokine-mediated regulation of chronic intestinal helminth infection. J. Exp. Med. 179:347-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelman, F. D., T. Shea-Donohue, J. Goldhill, C. A. Sullivan, S. C. Morris, K. B. Madden, W. C. Gause, and J. F. Urban, Jr. 1997. Cytokine regulation of host defense against parasitic gastrointestinal helminthes: lessons from studies with rodent models. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:505-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelman, F. D., and S. C. Morris. 1999. Development of an assay to measure in vivo cytokine production in the mouse. Int. Immunol. 11:1811-1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gately, M. K., L. M. Renzetti, J. Magram, A. S. Stern, L. Adorini, U. Gubler, and D. H. Presky. 1998. The interleukin-12/interleukin-12-receptor system: role in normal and pathologic immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:495-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, Y. W., and T. R. Malek. 1995. The IL-2 receptor gamma c chain does not function as a subunit shared by the IL-4 and IL-13 receptors. Implication for the structure of the IL-4 receptor. J. Immunol. 155:9-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain-Vora, S., A. M. LeVine, Z. Chroneos, G. F. Ross, W. M. Hull, and J. A. Whitsett. 1998. Interleukin-4 enhances pulmonary clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 66:4229-4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung, Y. J., R. LaCourse, L. Ryan, and R. J. North. 2002. Evidence inconsistent with a negative influence of T helper 2 cells on protection afforded by a dominant T helper 1 response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis lung infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 70:6436-6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Gros, G., S. Z. Ben-Sasson, R. Seder, F. D. Finkelman, and W. D. Paul. 1990. Generation of interleukin 4 (IL-4)-producing cells in vivo and in vitro: IL-2 and IL-4 are required for in vitro generation of IL-4-producing cells. J. Exp. Med. 172:921-929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, L., Y. Xia, A. Nguyen, Y. H. Lai, L. Feng, T. R. Mosmann, and D. Lo. 1999. Effects of Th2 cytokines on chemokine expression in the lung: IL-13 potently induces eotaxin expression by airway epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 162:2477-2487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuda, H., N. Watanabe, Y. Kiso, S. Hirota, H. Ushio, Y. Kannan, M. Azuma, H. Koyama, and Y. Kitamura. 1990. Necessity of IgE antibodies and mast cells for manifestation of resistance against larval Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks in mice. J. Immunol. 144:259-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mencacci, A., G. Del Sero, E. Cenci, C. F. d'Ostiani, A. Bacci, C. Montagnoli, M. Kopf, and L. Romani. 1998. Endogenous interleukin 4 is required for development of protective CD4+ T helper type 1 cell responses to Candida albicans. J. Exp. Med. 187:307-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mochizuki, M., J. Bartels, A. I. Mallet, E. Christophers, and J. M. Schroder. 1998. IL-4 induces eotaxin: a possible mechanism of selective eosinophil recruitment in helminth infection and atopy.J. Immunol. 160:60-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman, S. L., L. Gootee, C. Bucher, and W. E. Bullock. 1991. Inhibition of intracellular growth of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast cells by cytokine-activated human monocytes and macrophages. Infect. Immun. 159:737-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noben-Trauth, N., L. D. Shultz, F. Brombacher, J. F. Urban, Jr., H. Gu, and W. E. Paul. 1997. An interleukin 4 (IL-4)-independent pathway for CD4+ T-cell IL-4 production is revealed in IL-4 receptor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10838-10843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Garra, A. 1998. Cytokines induce the development of functionally heterogeneous T helper cell subsets. Immunity 8:275-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton, E. A., A. C. La Flamme, J. A. Pedras-Vasoncelos, and E. J. Pearce. 2002. Central role for interleukin-4 in regulating nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation and gamma interferon production. Infect. Immun. 70:177-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rankin, J. A., D. E. Picarella, G. P. Geba, U. A. Temann, B. Prasad, B. DiCosmo, A. Tarallo, B. Stripp, J. Whitsett, and R. A. Flavell. 1996. Phenotypic and physiologic characterization of transgenic mice expressing interleukin 4 in the lung: lymphocytic and eosinophilic inflammation without airway hyperreactivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7821-7825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen, B. J., T. Hage, and W. Sebald. 1996. Global and local determinants for the kinetics of interleukin-4/interleukin-4 receptor alpha chain interaction: a biosensor study employing recombinant interleukin-4-binding protein. Eur. J. Biochem. 240:252-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stack, R. M., D. J. Lenschow, G. S. Gray, J. A. Bluestone, and F. W. Fitch. 1994. IL-4 treatment of small splenic B cells induces costimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2. J. Immunol. 152:5723-5733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugawara, I., H. Yamada, S. Mizuno, and Y. Iwakura. 2000. IL-4 is required for defense against mycobacterial infection. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:971-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swain, S. L., A. D. Weinberg, M. English, and G. Huston. 1990. IL-4 directs the development of Th2-like helper effectors. J. Immunol. 145:3796-3806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urban, J. F., Jr., I. M. Katona, W. E. Paul, and F. D. Finkelman. 1991. Interleukin 4 is important in protective immunity to a gastrointestinal nematode infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:5513-5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urban, J. F., Jr., N. Noben-Trauth, D. D. Donaldson, K. B. Madden, S. C. Morris, M. Collins, and F. D. Finkelman. 1998. IL-13, IL-4Rα, and Stat6 are required for the expulsion of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunity 8:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu-Hsieh, B. A., G. S. Lee, M. Franco, and F. M. Hofman. 1992. Early activation of splenic macrophages by tumor necrosis factor alpha is important in determining the outcome of experimental histoplasmosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 60:4230-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou, P., G. Miller, and R. A. Seder. 1998. Factors involved in regulating primary and secondary immunity to infection with Histoplasma capsulatum: TNF-α plays a critical role in maintaining secondary immunity in the absence of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 160:1359-1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou, P., M. C. Sieve, J. Bennett, K. J. Kwon-Chung, R. P. Tewari, R. T. Gazzinelli, A. Sher, and R. A. Seder. 1995. IL-12 prevents mortality in mice infected with Histoplasma capsulatum through induction of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 155:785-795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann, N., S. P. Hogan, A. Mishra, E. B. Brandt, T. R. Bodette, S. M. Pope, F. D. Finkelman, and M. E. Rothenberg. 2000. Murine eotaxin-2: a constitutive eosinophil chemokine induced by allergen challenge and IL-4 overexpression. J. Immunol. 165:5839-5846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zurawski, S. M., P. Chomarat, O. Djossou, C. Bidaud, A. N. McKenzie, P. Miossec, J. Banchereau, and G. Zurawski. 1995. The primary binding subunit of the human interleukin-4 receptor is also a component of the interleukin-13 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:13869-13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zurawski, S. M., F. Vega, Jr., B. Huyghe, and G. Zurawski. 1993. Receptors for interleukin-13 and interleukin-4 are complex and share a novel component that functions in signal transduction. EMBO J. 12:2663-2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]