Abstract

Extracellular proton concentrations in the brain may be an important signal for neuron function. Proton concentrations change both acutely when synaptic vesicles release their acidic contents into the synaptic cleft and chronically during ischemia and seizures. However, the brain receptors that detect protons and their physiologic importance remain uncertain. Using organotypic hippocampal slices and biolistic transfection, we found the acid-sensing ion channel 1a (ASIC1a), localized in dendritic spines where it functioned as a proton receptor. ASIC1a also affected the density of spines, the postsynaptic site of most excitatory synapses. Decreasing ASIC1a reduced the number of spines, whereas overexpressing ASIC1a had the opposite effect. Ca2+-mediated Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) signaling was probably responsible, because acid evoked an ASIC1a-dependent elevation of spine intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and reducing or increasing ASIC1a levels caused parallel changes in CaMKII phosphorylation in vivo. Moreover, inhibiting CaMKII prevented ASIC1a from increasing spine density. These data indicate that ASIC1a functions as a postsynaptic proton receptor that influences intracellular Ca2+ concentration and CaMKII phosphorylation and thereby the density of dendritic spines. The results provide insight into how protons influence brain function and how they may contribute to pathophysiology.

Keywords: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, neuron, sodium channel, synapse

When synaptic vesicles fuse with the presynaptic membrane, they release neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft and activate neurotransmitter receptors on the postsynaptic membrane. Several measurements place synaptic vesicle pH at ≈5.2–5.7 (1–3). As a result, when synaptic vesicles discharge their contents, the pH at synapses may fall, especially during repeated discharge with release of multiple vesicles. Accordingly, several studies have detected acidification during synaptic transmission (4–6); for example, pH in the retinal ribbon synapse is estimated to drop 0.2–0.6 pH units during synaptic transmission (4, 6). In addition to physiological acidification during neurotransmission, central pH falls in disease states such as ischemia and seizure (7). Thus, understanding how protons regulate channels and its consequence on synapses may help us better understand neuronal function and provide insight into neurological diseases where acidosis is involved.

Interesting candidates for sensing protons are acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs). ASICs are activated by extracellular protons. They belong to the degenerin/epithelial Na+ channel family of nonvoltage gated cation channels (8–10). Four ASIC genes (ASIC1 to ASIC4) and splice variants (a and b) for ASIC1 and ASIC2 have been identified. ASIC subunits have two transmembrane domains and a large extracellular loop, and they function as homomultimers or heteromultimers to conduct Na+ and Ca2+. In the peripheral nervous system, ASICs contribute to mechanosensation, nociception, and responses of auditory neurons (11–15). In the CNS, neurons predominantly express ASIC1a, ASIC2a, and ASIC2b subunits (16, 17).

Of ASICs in the CNS, the ASIC1a subunit may play a particularly important role. ASIC1a in neurons is activated by pH ≤ 7 and shows half-maximum activation at pH 6.8–6.3 (18–20). Disrupting ASIC1a eliminated pH 5-evoked currents in cultured hippocampal, amygdala, and cortical neurons (17, 19, 21, 22). ASIC1a is also unique among ASICs in that homomultimeric ASIC1a channels conduct Ca2+ and Na+ (22–24). Loss of ASIC1a impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation (17). Moreover, disrupting ASIC1a impaired learning in paradigms involving hippocampus, cerebellum, and amygdala; ASIC1a null mice showed deficits in spatial learning, eye-blinking conditioning, and fear conditioning (17, 21). Conversely, overexpressing ASIC1a in transgenic mice increased fear conditioning (25).

Although these functional data indicate the importance of ASIC1a in CNS function, the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain. Some previous studies suggested ASIC1a may be present at synapses, although the cellular localization of ASIC1a is still controversial (16, 17, 21). Therefore, we examined the localization of ASIC1a in hippocampal slices. We found ASIC1a preferentially targeted to dendrites and present in spines. Surprisingly, ASIC1a influenced the density of dendritic spines. To understand the underlying mechanism, we then examined the involvement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII).

Results

ASIC1a Localized in Dendritic Spines in Hippocampal Slices.

Our previous studies suggested that ASIC1a might be present at synapses (17, 21, 25). In contrast, another report suggested a universal distribution of ASIC1 in cultured CNS neurons (16). To assess ASIC1a localization and function in a more physiologic environment, we turned to brain slices, which preserve the internal circuitry and closely resemble in vivo physiology (26).

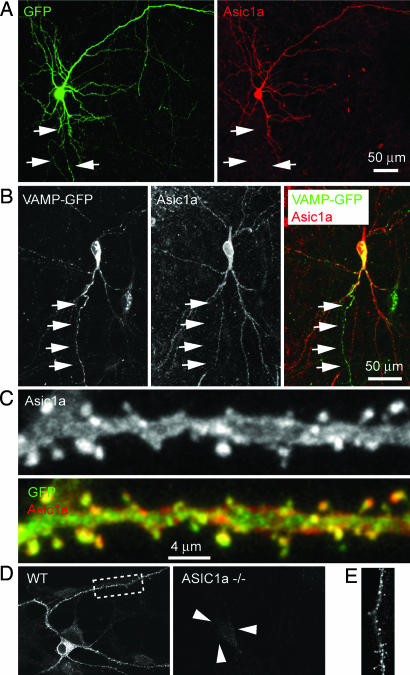

We cotransfected hippocampal slices biolistically with EGFP and Flag-tagged ASIC1a. Immunofluorescence (IF) showed ASIC1a preferentially targeted to dendrites; we could not detect it in processes that appeared to be axons (Fig. 1A). We further labeled axons with an axonal marker, vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2)/synaptobrevin (3), and failed to detect the presence of ASIC1a in VAMP2-EGFP labeled axons (Fig. 1B). ASIC1a IF was present in most spines (Fig. 1C). As a complement to our experiments expressing Flag-tagged ASIC1a, we immunostained endogenous ASIC1a in dissociated neurons. The pattern was similar; ASIC1a was present in both dendrites and dendritic spines (Fig. 1 D and E). These results indicate that ASIC1a had a preferential somatodendritic localization and was present in spine heads. This location positions ASIC1a where it could serve as a receptor for protons.

Fig. 1.

ASIC1a localized preferentially to dendrites in hippocampal slices. (A) 2D projection images of a CA1 pyramidal neuron that was cotransfected with EGFP and Flag-ASIC1a. ASIC1a IF (red) was apparent in all apical and basal dendritic branches. Arrows indicate the axon-like processes, which did not show detectable ASIC1a IF. (B) ASIC1a did not localize to axons. Slices were cotransfected with an axonal marker, VAMP2-eGFP, and Flag-ASIC1a. Arrows point to an axon identified by VAMP2-GFP fluorescence; ASIC1a IF was absent in it. We observed low levels of VAMP2-GFP signal in proximal ends of some dendrites, possibly caused by overexpression. (C) Enlarged view of an apical dendrite. Note that ASIC1a IF was present in spines and dendrites. (D) IF of endogenous ASIC1a in dissociated and cultured cortical neurons. ASIC1a IF is visible in cell body and dendrites of WT neuron but not those of ASIC1a knockout neuron. Arrowheads point to an ASIC1a knockout neuron, which shows only background fluorescence. The size of pyramidal neuronal cell body is usually 12–18 μm. (E) High-magnification view of boxed area from D. ASIC1a signal is present along dendritic shaft and in spines.

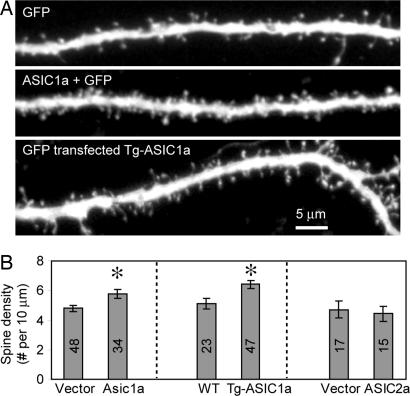

ASIC1a Increased the Density of Dendritic Spines.

While examining ASIC1a localization, we were surprised to find that transfecting hippocampal slice neurons with ASIC1a increased spine density >20% (Fig. 2). As an additional test, we studied hippocampal slices from ASIC1a transgenic mice and observed a similar increased spine density (Fig. 2). In contrast to the effects of ASIC1a, expressing ASIC2a, which is highly homologous to ASIC1a but much less pH-sensitive, failed to alter spine density (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Increasing ASIC1a increased the density of dendritic spines in brain slices. (A) Images showing EGFP fluorescence in dendrites transfected with EGFP (Top) or EGFP and ASIC1a (Middle). (Bottom) EGFP fluorescence in dendrites from a ASIC1a transgenic slice is shown. (B) Quantification of spine density was done by using 3D stacks with the operator blinded to the intervention. Tg-ASIC1a indicates mice transgenic for ASIC1a and transfected with EGFP. Asterisk indicates P < 0.01. Numbers indicate the number of neurons quantified from four (Left), two (Center), or three (Right) different experiments.

To learn whether reducing ASIC1a had the opposite effect, we examined slices from ASIC1a knockout mice. However, we found no significant alteration in spine density compared with WT neurons (data not shown). We speculate that compensation during development in the knockout model might have prevented an effect of decreased ASIC1a. Therefore, we reduced ASIC1a levels acutely by transfecting hippocampal neurons with ASIC1a siRNA constructs. ASIC1a siRNAs decreased ASIC1a protein levels in cell lines; siRNA1 appeared to be the most efficient (Fig. 3 A and B). Expressing siRNA1 but not a scrambled control in slice neurons reduced the density of dendritic spines by >30% (Fig. 3 C and D). As an independent strategy to inhibit ASIC1a function, we expressed an ASIC1a dominant-negative construct that contained the first 110 residues (DN-ASIC1a). Similar constructs have been used as dominant-negative proteins for several other degenerin/epithelial Na+ channel family proteins (27, 28). We tested the efficacy of DN-ASIC1a by measuring [Ca2+]i in ASIC1a overexpressing cells and found that it reduced the acid-induced [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 3E). Like siRNA, the DN-ASIC1a reduced spine density (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Reducing ASIC1a decreased spine density. (A) Western blot showing the effect of ASIC1a siRNA. Data are from CHO-K1 cells transiently transfected ASIC1a together with control vector or various ASIC1a siRNAs (siRNA1–siRNA3) constructs. ASIC1a protein was reduced by expression of all three ASIC1a siRNAs, with siRNA1 being the most efficient. Blots were reprobed with an actin antibody as a loading control. (B) Western blot showing the effect of ASIC1a siRNA in CHO-K1 cells stably expressing ASIC1a or ASIC2a under Tet-on promoter. Cells were transfected with control vector or various ASIC1a siRNAs (siRNA1–siRNA3) and scrambled constructs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, expression of ASIC1a or ASIC2a was induced by the addition of doxycycline (DOX) for 24 h. ASIC1a protein was reduced by expression of all three ASIC1a siRNAs but not by a scrambled siRNA control (Upper). ASIC2a expression was not affected by siRNAs. (C) Images showing EGFP fluorescence in a segment of apical dendrites from WT neurons expressing eGFP control, ASIC1a siRNA1 (siRNA1), scrambled siRNAs (scramble), or a dominant-negative ASIC1a (DN-ASIC1a). (D) Quantification of the effect of siRNA (Left), scrambled siRNA control (Center), and DN-ASIC1a (Right) on spine density. Data are from three different groups of experiments, hence the three different controls. Asterisk indicates P < 0.01 by Student's t test. (E) DN-ASIC1a inhibited the acid-induced [Ca2+]i increase in cells expressing ASIC1a. CHO-K1 cells were cotransfected with ASIC1a, YC3.60, and empty vector or DN-ASIC1a constructs. Imaging of [Ca2+]i was performed 24–48 h after transfection. Change in FRET (YFP/CFP ratio) was measured in response to pH 5 solution. Asterisks indicate P < 0.001 (Student's t test) compared with vector control. Numbers indicate number of neurons (D) or cells (E) quantified from three different experiments.

These data show that ASIC1a levels bidirectionally affect spine density in hippocampal neurons, with elevated ASIC1a associated with increased spine density and reduced ASIC1a with reduced spine density.

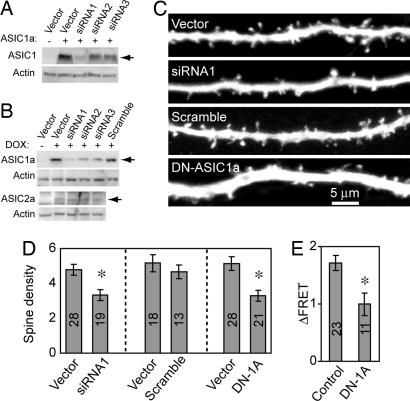

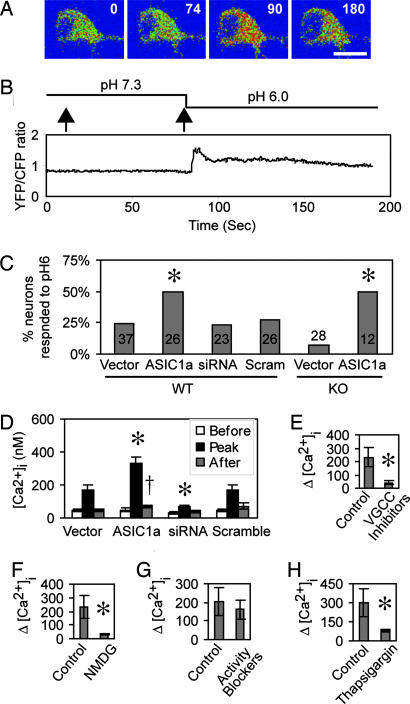

ASIC1a Mediated an Acid-Evoked [Ca2+]i Elevation in Hippocampal Slice Neurons.

Previous studies demonstrated the importance of [Ca2+]i in controlling the number of dendritic spines (29). We therefore asked whether ASIC1a functions as a postsynaptic proton receptor to influence [Ca2+]i.

Earlier work in heterologous cells and dissociated neurons showed that ASIC1a raised [Ca2+]i in response to an acidic stimulus (22–24). However, whether or not it responds to protons under physiological conditions is still not known. This may be an important distinction based on results obtained with peripheral ASIC channels. Large dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons contain ASICs in their specialized nerve endings. When these DRG neurons are removed and cultured, they show proton-gated currents (18, 30). In contrast, in the more physiologic skin–nerve preparation, acid application to the periphery fails to elicit any activity (31). Thus, it seemed critical to assess the role of ASIC1a in a more native environment. We measured changes in [Ca2+]i by transfecting neurons with a Ca2+ reporter, YC3.60 (32). YC3.60 is an improved version of cameleon and has a higher dynamic range over physiological [Ca2+], with a KD of 250 nM. To provide an acidic stimulus, we reduced the bath solution pH to 6.0. However, because the neurons lie inside the slice, the pH adjacent to the neuron was unknown, but may be less acidic than the bath solution.

Acid application increased YC3.60 FRET (Fig. 4A and B shows an example). [Ca2+]i increased in 24% of YC3.60-expressing neurons, and the percentage of responding neurons increased when we transfected ASIC1a (Fig. 4C). ASIC1a also affected the magnitude of the [Ca2+]i changes (Fig. 4D). Overexpression increased the peak [Ca2+]i after acidification, and 60 s after the peak, the [Ca2+]i remained elevated relative to control neurons (Fig. 4D). This result is consistent with earlier reports that there is a small sustained increase in [Ca2+]i during acid application (22). This component may be related to the neuronal injury associated with CNS acidosis during ischemia (7).

Fig. 4.

ASIC1a mediated the H+-evoked Ca2+ increase in hippocampal slice neurons. (A and B) WT hippocampal slices were transfected with cameleon YC3.60, and imaging of FRET from cameleon was performed to visualize changes in [Ca2+]i in response to application of a pH 6.0 solution. (A) Images showing ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence (blue indicates a low ratio, and red indicates a high ratio). Numbers are time (in seconds, see B) at which images were acquired. (Scale bar = 20 μm.) (B) Effect of pH 6 solution on YFP/CFP fluorescence ratio from the same neuron. (Upper) Interventions, including addition of pH 7.3 (as a control for the solution change) and pH 6.0 solutions at times indicated by arrows. (Lower) YFP/CFP ratio. The interval between acid application and the [Ca2+]i response varied from neuron to neuron (for other examples, note Fig. 5B), probably reflecting the time for the pH to change at the neuron surface. (C) Percentage of neurons responding to pH 6 solution with an increase in [Ca2+]i. Data are from WT or ASIC1a knockout (KO) neurons transfected with vector, ASIC1a, ASIC1a siRNA1 (siRNA), or a scrambled siRNA control (Scram). Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 by χ2 analysis. Numbers indicate the number of neurons analyzed. (D) [Ca2+]i before, during, and after (measured 60 s postpeak) pH 6.0 stimulation. Data are from control WT neurons transfected with vector (n = 9), ASIC1a (n = 10), ASIC1a siRNA1 (siRNA) (n = 7), or scrambled siRNA control (n = 7). All values for peak [Ca2+]i are significantly different from baseline, P < 0.01. Asterisk indicates difference compared with vector, P < 0.05. Dagger indicates difference compared with value before pH 6.0 application, P < 0.01. (E–H%) Quantification of acid-induced changes in [Ca2+]i under different conditions. Hippocampal slice neurons were cotransfected with ASIC1a and YC3.60. The same neuron was imaged first under control and then experimental conditions. (E) In the absence or presence of inhibitors for voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), inhibitors were 50 μM nifedipine, 200 nM ω-agatoxin IVA, 1 μM conotoxin MVIIA, and 1 μM conotoxin GVIA (n = 6). (F) In the presence or absence of extracellular Na+, Na+ was replaced by N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) (n = 4). (G) In the absence or presence of activity blockade mixture, inhibitors were 1 μM tetrodotoxin, 10 μM 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid, and 20 μM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (n = 8). (H) Without or with pretreatment with 1 μM of thapsigargin to deplete Ca2+ stores (n = 5). Asterisk indicates P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

Consistent with the reduced amount of ASIC1a protein, siRNA1 greatly attenuated the magnitude of the [Ca2+]i elevation (Fig. 4D) without changing the percentage of H+-responding neurons (Fig. 4C). A scrambled control had no effect. In ASIC1a−/− slices, the percentage of proton-responding neurons tended to fall; this defect was rescued by expressing ASIC1a (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrating that acidic pH activates ASIC channels in brain slices argue that ASICs can respond to protons in vivo.

ASIC1a activation might increase [Ca2+]i in two ways: ASIC1a homomultimers might directly raise [Ca2+]i (22–24) or Na+-conducting ASIC1a subunits might activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to increase [Ca2+]i. We found that a mixture of inhibitors for voltage-gated (L, N, P, and Q types) Ca2+ channels significantly attenuated the acid-evoked [Ca2+]i rise (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that a substantial component of the [Ca2+]i elevation is indirect, whereas a minor proportion may occur through ASIC1a channels. Consistent with this speculation, replacing extracellular Na+ with N-methyl-d-glucamine largely eliminated the proton-activated [Ca2+]i increase (Fig. 4F).

Because neuronal activity might affect [Ca2+]i, we treated slice neurons with a mixture of inhibitors for neural activity (tetrodotoxin, 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione, and 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid). This treatment did not significantly change the proton-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4G). Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release is known to contribute to [Ca2+]i elevations in neurons and other cells. To test the contribution of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, we depleted stores by pretreating with thapsigargin. Thapsigargin reduced the acid-induced [Ca2+]i increase by 70% (Fig. 4H).

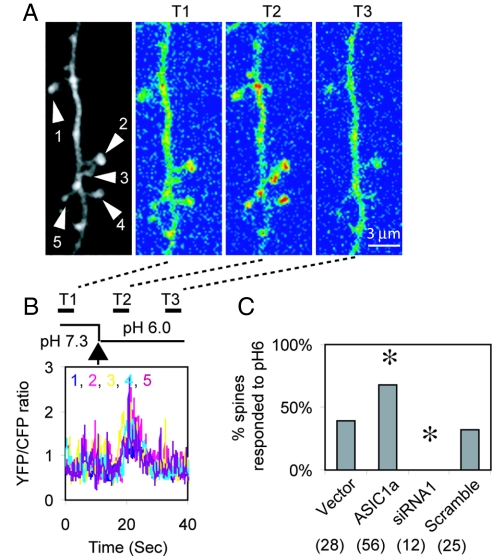

These data plus the presence of ASIC1a in spines predicted that acid would increase [Ca2+]i at that location. Fig. 5A and B shows that applying an acidic solution stimulated a [Ca2+]i increase in spines of a neuron transfected with ASIC1a. We also observed a [Ca2+]i increase in dendritic shafts, although the response was variable (Fig. 5A and data not shown). When we transfected ASIC1a, the percentage of responding spines increased compared with a vector control (Fig. 5C). In contrast, when we reduced ASIC1a with siRNA1, spine [Ca2+]i failed to rise. A scrambled control siRNA had no effect.

Fig. 5.

Acid-evoked [Ca2+]i increase in dendritic spines. (A) Image on left shows a segment of an apical dendrite from a neuron cotransfected with ASIC1a and YC3.60. Images T1–T3 show the YFP/CFP fluorescence ratio (blue indicates a low ratio and red indicates a high ratio) obtained at times indicated by black bars at the top of B. To minimize noise, each ratio image is an average of 25 consecutive scans (3.7 s). Arrowheads indicate five spines where FRET was quantified in B. (B) YFP/CFP ratio of spine heads indicated in A. (C) Percentage of spines responding to pH 6 solution with an increase in [Ca2+]i. Hippocampal slice neurons were cotransfected with YC3.60 and either a vector control, ASIC1a, siRNA1, or a scrambled siRNA. Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of spines quantified from 12 ASIC1a, 6 Vector, 5 siRNA, and 7 scrambled RNAi neurons, each from a different slice. Asterisks indicates significant difference (P < 0.05 by χ2 test) from vector control.

These data indicate that ASIC1a mediates an acid-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation in the dendritic spines of hippocampal neurons, implying that ASIC1a contributes to Ca2+-mediated signaling in CNS neurons. Thus, ASIC1a-dependent changes in [Ca2+]i may have mediated the changes in spine density.

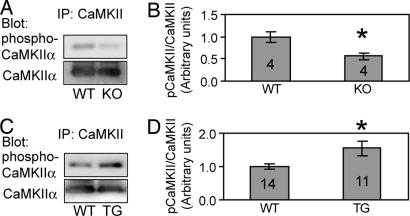

ASIC1a Affected CaMKII Phosphorylation in Brain.

If ASIC1a is physiologically activated in vivo, it could have important consequences for targets downstream of [Ca2+]i. CaMKII is one of the most abundant Ca2+-regulated molecules in neurons (33). When [Ca2+]i increases, CaMKIIα becomes phosphorylated on Thr-286. We therefore probed whole brain CaMKIIα with an antibody specific to the Thr-286 phosphorylated form to determine whether ASIC1a levels affect CaMKII phosphorylation.

Loss of ASIC1a decreased CaMKIIα Thr-286 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A and B). Conversely, neuronal overexpression of ASIC1a in a transgenic mouse increased CaMKIIα Thr-286 phosphorylation (Fig. 6 C and D). These data are consistent with our [Ca2+]i measurements and suggest parallel changes in CaMKIIβ phosphorylation. More importantly, these results indicate that the ASIC1a level influences Ca2+-dependent regulation in vivo.

Fig. 6.

ASIC1a levels regulate CaMKII phosphorylation in vivo. (A) CaMKII was immunoprecipitated (IP) and then blotted with antibody to phosphorylated CaMKIIα (Upper) or total CaMKII from WT and ASIC1a knockout (KO) brains (Lower). (B) Quantification of CaMKII phosphorylation. Asterisk indicates P < 0.05 (Student's t test) compared with WT brain. Numbers indicate number of animals. (C and D) CaMKII phosphorylation of brain from WT and ASIC1a transgenic (TG) animals.

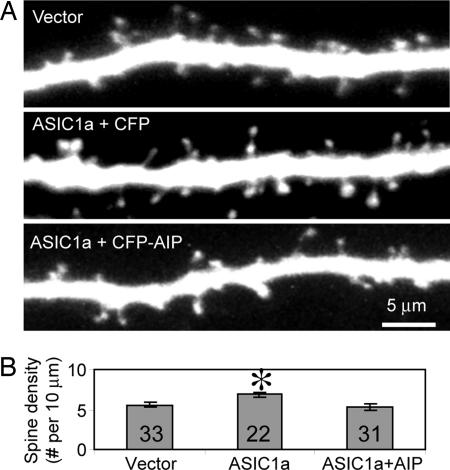

Inhibiting CaMKII Activity Blocked the ASIC1a-Induced Increase in Spine Density.

Finding that ASIC1a affects CaMKII phosphorylation led us to ask whether ASIC1a affects spines through CaMKII. This question was based on earlier studies showing the importance of CaMKII in spine remodeling (34, 35). Therefore, we tested this possibility by expressing a specific peptide inhibitor of CaMKII, autocamtide-2 related inhibitory peptide (AIP; KKALRRQEAVDAL) (36) (J. Bok and S.H.G., unpublished data). AIP abolished the ASIC1a-induced increase in spine density (Fig. 7), indicating that CaMKII activity was required for the increase.

Fig. 7.

The CaMKII inhibitory peptide AIP inhibited the ASIC1a-induced increase in spine density. (A) Images showing a segment of apical dendrites from WT neurons expressing control (EGFP), ASIC1a and ECFP, or ASIC1a and CFP-AIP. Images shown are 2D projections of 3D stacks. (B) Quantification of the effect of AIP on spine density. Asterisk indicates P < 0.05 by Student's t test. Numbers indicate number of neurons quantified from three different experiments.

Discussion

Distinct synapses use different neurotransmitters. In contrast, all synaptic vesicles are acidic, and therefore neurotransmission may acidify synaptic clefts throughout the CNS (37). Our data place ASIC1a in the postsynaptic membrane and other sites and show that it can function as a proton receptor in spines. It affects [Ca2+]i and CaMKII phosphorylation, and the persistent signaling via ASIC1a over a period of hours to days mediates structural plasticity, altering the density of dendritic spines, the major site of excitatory neurotransmission.

ASIC1a Is a Proton Receptor at Dendritic Spines.

Protons modulate the function of several synaptic membrane ion channels. For example, at the presynaptic membrane, H+ inhibits voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to reduce vesicle release (4, 6, 38). At the postsynaptic membrane, H+ inhibits NMDA receptors (39, 40) and increases the conductance of G protein-coupled inward rectifier K+ channels (41). In each of these cases, H+ modulates the functional response of ion channels to voltage or some other neurotransmitter. In contrast, H+ directly regulates ASIC channels.

It is also interesting that proton activation of ASIC1a would predict opposite effects on synaptic function from proton modulation of other synaptic membrane ion channels. Acid-induced alterations of the other ion channels described above would attenuate [Ca2+]i elevations and/or neurotransmission. In contrast, ASIC1a activation would predict enhanced postsynaptic responses by further increasing [Ca2+]i. ASIC1a-dependent phosphorylation of CaMKII supports this prediction. Thus, ASIC1a activation may counteract the tendency of protons to inhibit synaptic activity.

ASIC1a Mediates an Increase in [Ca2+]i.

We previously showed that disrupting the ASIC1a gene eliminated currents evoked by pH 5 in cultured neurons (17, 19, 21, 22). Here, we found that loss of ASIC1a markedly attenuated acid-induced [Ca2+]i elevations in hippocampal slice neurons. Conversely, overexpressing ASIC1a increased the H+-evoked rise in [Ca2+]i. Previous studies in heterologous cells showed most of the Ca2+ influx occurred through ASIC1a channels (24). In contrast, our brain slice data suggest that much of the ASIC1a-induced [Ca2+]i increase was secondary, resulting from activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. A smaller fraction may have been through conduction of Ca2+ by ASIC1a homomultimers. These findings suggest additional mechanisms by which ASIC1a may influence [Ca2+]i.

Although our results demonstrate the involvement of ASIC1a in controlling [Ca2+]i, several considerations limit the quantitative aspects of these data. First, the results probably represent a minimal estimate of the percentage of acid-responding neurons because we applied acid to the slice surface, and the pH beneath the surface adjacent to the neuron was unknown. Second, in heterologous cells and cultured neurons the maximal current response occurs with rapid acidification, whereas the changes we induced may be relatively slow at the neuronal membrane. Third, because we do not know absolute changes in pH in the synaptic cleft or their time course, it is not possible to predict the extent to which ASIC1a will alter [Ca2+]i.

Implications for Spine Remodeling and Disease.

Our data reveal a role for ASIC1a in regulating spine density and emphasize the potentially important role of ASIC1a in modulating neuronal function. Because ASIC1a affected [Ca2+]i, and previous studies demonstrated that [Ca2+]i plays a key role in determining the density of spines (29), we speculate that changes in spine density result from altered Ca2+ homeostasis over a period of hours to days. Interestingly, activation of one important target of Ca2+, CaMKII, is reported to be sufficient and necessary for spine formation and growth (34, 35), although another study found that CaMKII activation causes a decrease in the total number of synaptic contacts (42). Finding that increased ASIC1a enhanced and decreased ASIC1a reduced CaMKII phosphorylation implicates CaMKII activation as a mediator. The observation that inhibiting CaMKII prevented the ASIC1a-induced increase in spine density supports this speculation. It is also interesting that CaMKII phosphorylates ASIC1a and increases its current (43). These results may suggest a positive feedback between CaMKII and ASIC1a activity.

Finding that ASIC1a modulated neuronal [Ca2+]i, CaMKII phosphorylation, and spine density may help explain earlier observations about the effect of ASIC1a on models of learning. For example, loss of ASIC1a impaired while increasing ASIC1a enhanced fear conditioning (17, 21, 25). However, it is interesting that ASIC1a null animals did not show a reduced spine density, even though there was a tendency for a reduced percentage of neurons with an acid-induced [Ca2+]i increase and a reduction in CaMKII phosphorylation. The reason for this difference is uncertain, but we speculate that compensatory processes during development might have minimized the modulatory effect of losing ASIC1a.

ASICs may also be involved in disease. Acute insults such as ischemia and seizure reduce brain pH (7). Although we found that most of the H+-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i was transient, [Ca2+]i remained elevated during acidosis. The increased [Ca2+]i may contribute to neuronal injury as suggested in recent studies showing the involvement of ASIC1a in acid-induced cell death in vitro (22, 24, 43). Moreover, ASIC1a knockout mice showed partial protection against ischemia-induced cell death in vivo. In addition to acidosis, several chronic brain diseases are characterized by altered dendritic spine density (44). Our finding that ASIC1a influences neuronal spine density raises the possibility that ASIC1a might be involved in the pathogenesis of disease, and if so, it might serve as a therapeutic target.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods are provided in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Hippocampal Slice Culture and Transfection.

Mouse hippocampal organotypic slice culture, transfection, and IF were modified from earlier studies (45, 46). See Supporting Text.

Confocal Microscopy and Ca2+ Imaging.

Confocal and multiphoton images were captured by using a two-photon microscope. For Ca2+ imaging, cameleon was excited with a 780 IR laser, and emission signals were collected by using a 515 beam splitter and 560/80 (yellow fluorescent protein, YFP) and 480/60 (cyan fluorescent protein, CFP) emission filters. See Supporting Text.

Lysate Preparation, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blot.

Mouse brain was lysed in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.4/1% Triton X-100/150 mM NaCl with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4°C. Standard Western blot procedure was performed. See Supporting Text.

Spine Analysis.

Dendritic spines were analyzed blind by using 3D image stacks as described (45). See Supporting Text.

Neuronal Culture and Immunostaining.

Cortical neuronal culture and immunostaining was performed as described (25). See Supporting Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Miyawaki (RIKEN, Saitomo, Japan), G. Miesenböck (Yale University, New Haven, CT), and D. Piston (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) for YC3.60, VAMP2, and cerulean constructs, respectively; J. Hell (University of Iowa) for CaMKII antibodies and comments; K. Rod and D. Anderson for technical assistance and spine quantification; T. Moninger (Central Microscopy Research Facility, University of Iowa) for help with two-photon imaging; H. Gong for making ASIC1a and ASIC2a stably transfected cell lines; and T. Nesselhauf and P. Hughes for cell culture. This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Grants R458-CR02 and ENGLH9850 and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK54759. S.H.G. was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC02961. X-m.Z. is an Associate and M.J.W. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. J.A.W. was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Advanced Research Career Development Award, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression Young Investigatory Award, and Anxiety Disorders Association of America Young Investigator Award.

Abbreviations

- ASIC

acid-sensing ion channel

- CaMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- IF

immunofluorescence

- VAMP2

vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

- AIP

autocamtide-2 related inhibitory peptide

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fuldner HH, Stadler H. Eur J Biochem. 1982;121:519–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb05817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaelson DM, Angel I. Life Sci. 1980;27:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVries SH. Neuron. 2001;32:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishtal OA, Osipchuk YV, Shelest TN, Smirnoff SV. Brain Res. 1987;436:352–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91678-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer MJ, Hull C, Vigh J, von Gersdorff H. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11332–11341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11332.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siesjo BK, Katsura K, Mellergard P, Ekholm A, Lundgren J, Smith ML. Prog Brain Res. 1993;96:23–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianchi L, Driscoll M. Neuron. 2002;34:337–340. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishtal O. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:477–483. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh MJ, Price MP, Xie J. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2369–2372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng BG, Ahmad S, Chen S, Chen P, Price MP, Lin X. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10167–10175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3196-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez de la Rosa D, Zhang P, Shao D, White F, Canessa CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2326–2331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price MP, McIlwrath SL, Xie J, Cheng C, Qiao J, Tarr DE, Sluka KA, Brennan TJ, Lewin GR, Welsh MJ. Neuron. 2001;32:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price MP, Lewin GR, McIlwrath SL, Cheng C, Xie J, Heppenstall PA, Stucky CL, Mannsfeldt AG, Brennan TJ, Drummond HA, et al. Nature. 2000;407:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35039512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones RC, 3rd, Xu L, Gebhart GF. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10981–10989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez de la Rosa D, Krueger SR, Kolar A, Shao D, Fitzsimonds RM, Canessa CM. J Physiol (London) 2003;546:77–87. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wemmie JA, Chen J, Askwith CC, Hruska-Hageman AM, Price MP, Nolan BC, Yoder PG, Lamani E, Hoshi T, Freeman JH, Jr, Welsh MJ. Neuron. 2002;34:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00661-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson CJ, Xie J, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Henss JM, Welsh MJ, Snyder PM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2338–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Askwith CC, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Rokhlina T, Welsh MJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18296–18305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron A, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. J Physiol (London) 2002;539:485–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wemmie JA, Askwith CC, Lamani E, Cassell MD, Freeman JH, Jr, Welsh MJ. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5496–5502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05496.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong ZG, Zhu XM, Chu XP, Minami M, Hey J, Wei WL, MacDonald JF, Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ, Simon RP. Cell. 2004;118:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. Nature. 1997;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yermolaieva O, Leonard AS, Schnizler MK, Abboud FM, Welsh MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6752–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wemmie JA, Coryell MW, Askwith CC, Lamani E, Leonard AS, Sigmund CD, Welsh MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahr BA. J Neurosci Res. 1995;42:294–305. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490420303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams CM, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27295–27300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong K, Mano I, Driscoll M. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2575–2588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02575.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Segal I, Korkotian I, Murphy DD. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01499-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishtal OA, Pidoplichko VI. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2325–2327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewin GR, Stucky CL. In: Molecular Basis of Pain Induction. Wood JN, editor. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:175–190. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jourdain P, Fukunaga K, Muller D. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10645–10649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10645.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fink CC, Bayer KU, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Schulman H, Meyer T. Neuron. 2003;39:283–297. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishida A, Shigeri Y, Tatsu Y, Uegaki K, Kameshita I, Okuno S, Kitani T, Yumoto N, Fujisawa H. FEBS Lett. 1998;427:115–118. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traynelis SF, Chesler M. Neuron. 2001;32:960–962. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vessey JP, Stratis AK, Daniels BA, Da Silva N, Jonz MG, Lalonde MR, Baldridge WH, Barnes S. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4108–4117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5253-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang CM, Dichter M, Morad M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6445–6449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Traynelis SF, Cull-Candy SG. Nature. 1990;345:347–350. doi: 10.1038/345347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mao J, Li L, McManus M, Wu J, Cui N, Jiang C. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46166–46171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pratt KG, Watt AJ, Griffith LC, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Neuron. 2003;39:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao J, Duan B, Wang DG, Deng XH, Zhang GY, Xu L, Xu TL. Neuron. 2005;48:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiala JC, Spacek J, Harris KM. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:29–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zha XM, Green SH, Dailey ME. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marrs GS, Green SH, Dailey ME. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1006–1013. doi: 10.1038/nn717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.