Abstract

We have tested the effect of the gap junction inhibitor, 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18βGA) on electromechanical coupling in the guinea-pig renal pelvis and ureter by the sucrose gap technique.

In the ureter 18βGA (3–30 μM) produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of the spike component of the action potential (AP) and reduced contraction evoked by electrical stimulation.

Neurokinin A (NKA) produced a slow depolarization with superimposed APs and phasic contractions of the ureter. 18βGA (30 μM) markedly inhibited the depolarization and APs evoked by NKA. However the contractile response was more sustained in the presence than in the absence of 18βGA. At 100 μM, 18βGA inhibited the mechanical responses to NKA.

KCl (80 mM) produced APs and phasic contractions followed by sustained depolarization and tonic contraction. At 30 μM 18βGA markedly inhibited the KCl-evoked APs and phasic contractions without affecting the sustained responses. At 100 μM 18βGA inhibited the tonic contraction to KCl.

In the renal pelvis 18βGA (30 μM) inhibited the amplitude of pacemaker potentials and accompanying contractions and induced the appearance of low-amplitude APs not associated with contraction.

We conclude that, up to 30 μM, the action of 18βGA is consistent with an inhibition of cell-to-cell electrical coupling via gap junctions. The single-unit character of smooth muscles in the guinea-pig upper urinary tract is partly converted to a multi-unit pattern. At high concentrations 18βGA possesses non specific effects which limit its usefulness as a tool for studying the role of gap junctions in smooth muscles.

Keywords: Guinea-pig renal pelvis, guinea-pig ureter, 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, neurokinin A, electromechanical coupling

Introduction

Gap junctions consist of aggregates of channels embedded in the plasma membrane of adjacent cells which enable the direct exchange of cytoplasmic ions and small molecules (Loewenstein 1987; Willecke et al., 1991). Intercellular communication via gap junctions is thought to regulate a number of functions: in smooth muscle this is considered a major mechanism for determining electrical coupling between adjacent cells (Gabella 1994 for review).

The degree of intercellular coupling varies from one smooth muscle to another and may determine at which extent a given smooth muscle organ exhibit a single-unit or multi-unit behaviour (Bozler 1942a,1942b). An extreme example of single-unit behaviour occurs in the upper urinary tract (renal pelvis and ureter): at this level a single action potential can spread through the functional syncitium of the renal pelvis and ureter to determine a synchronized and propagated contraction which subserves ureteral peristalsis (Santicioli and Maggi, 1998 for review).

A saponin isolated from licorice roots, 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18βGA) has been shown to cause the disappearance of gap junction plaques in rat liver epithelial cells (Davidson et al., 1986). The disassembly of gap junction plaques by 18βGA has been reported to involve the dephosphorylation of connexin-43 (C×43), the protein subunit forming the gap junction channels (Guan et al., 1996).

18βGA has been recently considered as a potential tool for studying the role, of gap junction in electrical coupling between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in mesenteric arteries (Yamamoto et al., 1998; 1999). The 18α form of GA has also been used for similar purposes (Taylor et al., 1998). In this study we have investigated the effect of 18βGA on electromechanical coupling in the spontaneously active guinea-pig renal pelvis and in the electrically-driven smooth muscle of the guinea-pig ureter by the sucrose gap method. We also studied the effect of 18βGA on the electrical and mechanical responses induced by neurokinin A (NKA) and KCl in the ureter: NKA was chosen as a stimulus since this neuropeptide is a major excitatory physiological transmitter in the guinea-pig upper urinary tract (Santicioli & Maggi, 1998 for review).

Altogether, the findings presented in this study indicate that, up to 30 μM, 18βGA modifies electromechanical coupling of the guinea-pig upper urinary tract in a manner which is consistent with inhibition of cell-to-cell communication via gap junctions: in particular, the single unit character of spontaneous (renal pelvis) or stimulated (ureter) electrical activity of the preparations is converted, under the action of 18βGA, to a multi-unit pattern.

Methods

Sucrose gap recording of electrical and mechanical activity were obtained from specimens of the renal pelvis and ureter excised from male Dunkin Hartley guinea-pigs (250–400 g body weight; Charles River Italy) as described previously (Santicioli & Maggi 1997; Patacchini et al., 1998). The guinea-pigs were stunned and bled, the whole kidney or ureter were excised and placed in oxygenated (96% O2 and 4% CO2) Krebs solution having the following composition (mM): NaCl, 119; NaHCO3, 25; KH2PO4, 1.2; MgSO4, 1.5; CaCl2, 2.5; KCl, 4.7 and glucose 11.

The renal pelvis was carefully dissected from the renal parenchyma under a binocular microscope, cleaned of adhering fat and connective tissue: circularly-oriented muscle strips were cut from the proximal region (close to the kidney). The ureters were cleaned of adhering fat and connective tissue and longitudinal segments (10–15 mm long) were prepared.

Before setup all preparations were exposed to capsaicin (10 μM for 15 min), in order to block the release of sensory neuropeptides from primary afferent neurons (Santicioli & Maggi 1997; Patacchini et al., 1998).

A single sucrose-gap, modified as described in details by Artemenko et al. (1982) and Hoyle (1987), was used to investigate simultaneously changes in membrane potential and contractile activity of the guinea-pig ureter and renal pelvis in response to chemical or electrical stimulation.

All preparations were continuously superfused (1 ml min−1) with oxygenated (96% O2 and 4% CO2) and warmed (35±0.5°C) Krebs solution.

18βGA (3–100 μM) was applied in superfusion for 30 min: in each case, control-matched experiments were performed with the vehicle (DMSO 0.1%).

In the guinea-pig ureter, after a 30 min equilibration period, the preparations were stimulated (electrical field stimulation, EFS) by application of twin pulses by using parameters of stimulation which were sufficient to produce direct excitation of smooth muscle (40–60 V, 1.8–3.2 mA, 1–3 ms pulse width); the stimuli were automatically delivered at 2.5 min intervals by means of a Grass S88 stimulator coupled to a stimulus isolator and a constant current unit (all from Grass).

In a separate series of experiments the guinea-pig ureter was stimulated by application of neurokinin A (NKA, 3 μM for 15 s) or by high-K Krebs solution (80 mM for 3 min; K isoosmotically substituted for Na) applied in superfusion at 45 min intervals.

The proximal renal pelvis developed, within few min from setup a regular series of spontaneous (pacemaker) action potentials (Santicioli & Maggi, 1997): when the spontaneous activity had reached a steady state, 18βGA was applied in superfusion and its effects were studied for 30 min.

All recordings of membrane potential and contractile activity were digitized and stored on a power Macintosh 6100/66 PC using MacLab/8s hardwere and analysed using MacLab Chart 3.4.2/s software.

Statistical analysis

All data in the text and figures are means±standard error of the mean (s.e.m). Statistical analysis was performed by means of Student's t-test for paired or umpaired data or by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet multiple comparison test, when applicable.

A P level <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Drugs

18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, nifedipine and capsaicin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). NKA was from Peninsula Laboratories (St. Helens, UK). 18ß-glycyrrhetinic acid was dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) at the concentration of 100 mM. The final vehicle (DMSO) concentration employed in the Krebs solution was 0.1%.

The other reagents were of the highest purity available from commercial sources.

Results

Effect of 18βGA on electromechanical coupling in the guinea-pig ureter

All preparations were electrically and mechanically quiescent. Application of EFS produced action potentials (APs) (22.8±1.0 mV; n=22) characterized by a rapidly rising depolarization followed by a plateau with superimposed spikes and repolarization. Each electrically-evoked AP was accompanied by a phasic contraction (3.9±0.25 mN; n=22).

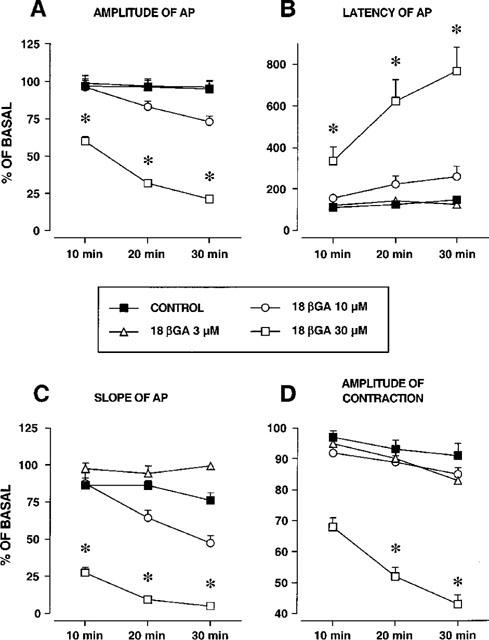

Superfusion with 18ßGA (3–30 μM, for 30 min) did not affect the resting membrane potential and basal tone of the guinea-pig ureter but markedly affected the EFS-evoked APs and accompanying contraction (Figures 1 and 2). The effects of 18ßGA include a concentration- and time-dependent inhibition of the amplitude of APs, a progressive suppression of superimposed spikes, a decrease of the APs slope, a marked increase in the latency of APs and a decrease in the amplitude of accompanying phasic contraction (Figure 1A). All these effects reached the level of statistical significance (P<0.05) at a concentration of 30 μM (Figure 2).

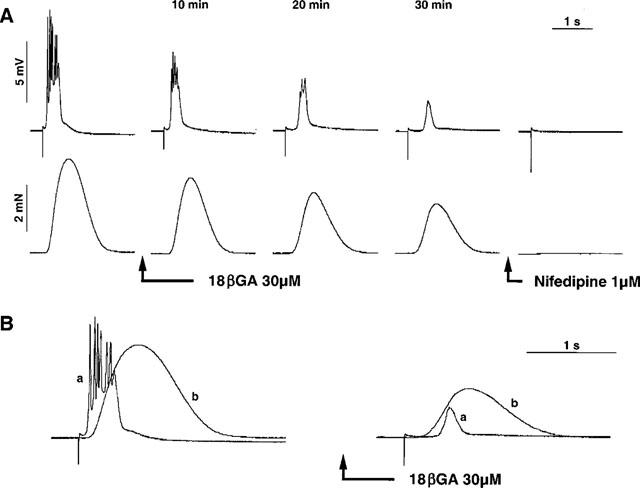

Figure 1.

(A) tracing illustrating the time-dependent effect of 18βGA (30 μM) on the EFS-evoked AP of the guinea-pig ureter. Note that 18βGA abolished the spike component of the AP and reduced contraction. At 30 min from start of superfusion with 18βGA, a bell-shaped AP with long latency was recorded in the presence of 18βGA. Nifedipine 1 μM promptly aboplished the residual electrical and mechanical responses to EFS receorded in the presence of 18βGA. (B) shows the electrical (a) and mechanical (b) responses to EFS measured before and 30 min after addition of 18βGA on an expanded time-scale: note that, in the presence of 18βGA the contractile response to EFS ensued before an electrical event was detectable at this time (see discussion). Calibration bars in A also apply to B.

Figure 2.

Concentration- and time-dependency of the effect of 18βGA on amplitude (A), latency (B), slope (C) of action potential (AP) and accompanying contraction induced by EFS in the guinea-pig ureter. Each value is mean±s.e.mean of 5–7 experiments. *Significantly different from control P<0.05.

At 30 min from addition of 30 μM 18ßGA a residual, bell-shaped AP and contraction were observed in response to EFS (Figure 1B): in these conditions, the residual EFS-evoked AP had a prolonged latency (from 49±6 to 326±20 ms in the absence and presence of 18βGA, n=7, P<0.05) and the contractile response ensued before the onset of the AP (Figure 1B). Notably, despite a 50% reduction in the amplitude of evoked contraction by 18βGA (Figure 2D), the duration of the evoked contraction was not appreciably inhibited by the drug (the duration of contraction, measured at 90% of relaxation, averaged 1426±67 and 1301±66 s in the absence and in the presence of 18βGA, respectively, n.s., n=7). The superfusion with nifedipine (1 μM) totally suppressed all residual electrical and mechanical activities observed in presence of 18βGA (Figure 1A).

Superfusion with NKA (3 μM for 15 s) produced a slow membrane depolarization (4.1±0.6 mV; n=16) onto which APs were superimposed. The NKA-evoked APs were characterized by a rapidly rising depolarization (18.5±1.4 mV) and a prolonged plateau. The NKA-evoked APs were accompanied by phasic contractions (5.3±0.3 mN) (Figure 3).

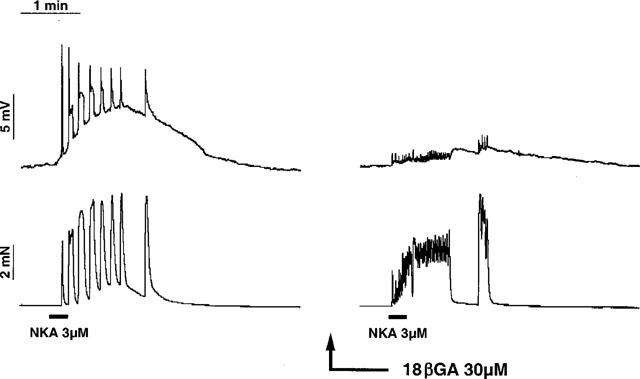

Figure 3.

Tracing illustrating the effect of 18βGA (30 μM for 30 min) on the electrical and mechanical responses induced by NKA (3 μM for 15 s) in the guinea-pig ureter. In control conditions NKA induced a slow depolarization with superimposed action potentials and phasic contractions. In the presence of 18βGA the electrical response to NKA were markedly diminished although a number of low amplitude action potentials were evoked; these were associated with low amplitude phasic contractions which fused together to produce a sustained tonic type contraction of the ureter smooth muscle.

Addition of 18βGA (30 μM, for 30 min) to the perfusion medium decreased the amplitude of the slow depolarization (1.41±0.58 mV, n=10, P<0.05 as compared to control) and superimposed APs (7.6±1.6 mV, P<0.05 as compared to controls) evoked by NKA.

In six out of ten cases tested (Figure 3) the residual electrical activity induced by NKA was accompanied by the development of a tonic type contractions onto which multiple low-amplitude phasic contractions superimposed.

On average, the maximal amplitude of the NKA-evoked contractions was unchanged by 18βGA (5.3±0.3 and 5.5±0.4 mN in the absence and presence of 18bGA, n=10, n.s.). However the integral of total contraction developed in response to NKA was significantly increased by 18βGA (110±22 and 164±25 mN.s in the absence and presence of 18βGA, respectively, n=10, P<0.05).

A higher concentration of 18βGA (100 μM) was also tested in four preparations: this produced a further reduction of all parameters examined, including a 41 and 61% inhibition of the maximal contraction and integral of contractile activity recorded in the presence of NKA, respectively (data not shown).

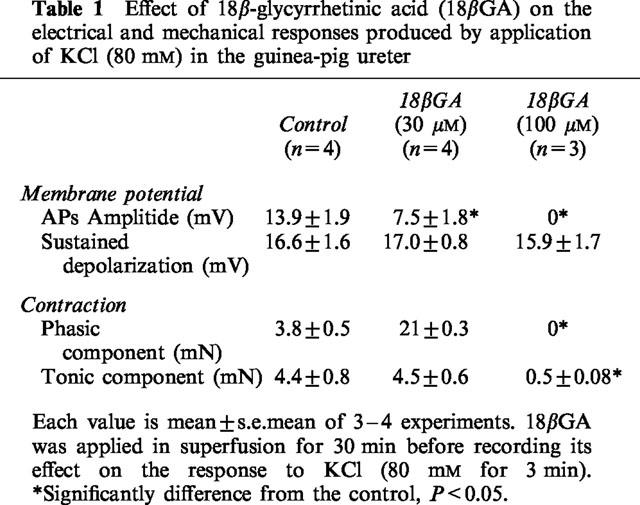

Superfusion with high K Krebs solution (80 mM for 3 min) transiently induced the firing of APs accompanied by phasic contractions followed by a sustained membrane depolarization and tonic contraction (cf. Maggi et al., 1996, Table 1). Superfusion with 18ßGA (30 μM for 30 min) did not significantly affect the amplitude of the slow depolarization (and of the tonic component of contraction induced by high K Krebs solution) but significantly reduced the amplitude of APs and the concomitant phasic contractile activity (Table 1). At 100 μM 18ßGA completely blocked APs and concomitant phasic contractions and strongly inhibited the amplitude of the tonic contraction, whereas the sustained depolarization was unchanged (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18βGA) on the electrical and mechanical responses produced by application of KCl (80 mM) in the guinea-pig ureter

Effect of 18βGA on electromechanical coupling in the guinea-pig renal pelvis

Circularly-oriented muscle strips from the guinea-pig proximal renal pelvis developed a regular and long-lasting spontaneous electrical and mechanical activity at a mean frequency of 4.6±0.1 cycles min−1 (n=22) and an average amplitude of depolarization and contraction of 6.0±0.6 mV and 2.4±0.2 mN, respectively.

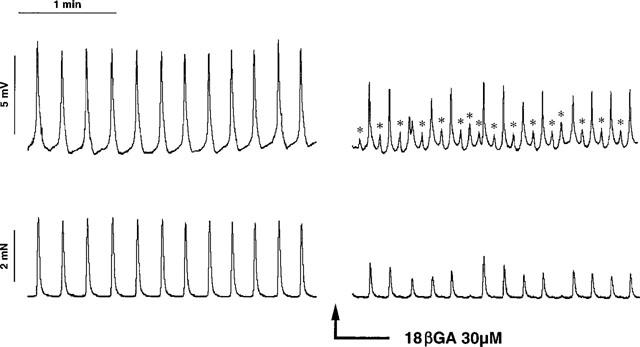

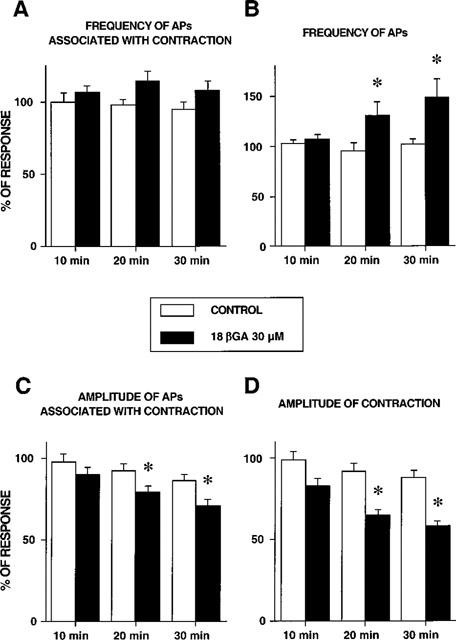

18βGA (30 μM) produced complex changes in the pacemaker potentials of the proximal renal pelvis. In control conditions each pacemaker potential was accompanied by a phasic contraction of the renal pelvis: the application of 18βGA, while decreasing the amplitude of pacemaker potential and the amplitude of accompanying phasic contractions, also induced (in eight out of 11 cases tested) the appearance of low amplitude APs (range 0.5–3.9 mV) which were not accompanied by a contractile activity (Figure 4). On the whole, if considering the frequency of pacemaker potentials accompanied by phasic contractions, this parameter was not significantly affected by 18βGA (Figure 5A). However, the frequency of all pacemaker potentials fired by the proximal renal pelvis (whether or not accompanied by contraction) was actually increased in the presence of 18βGA (Figure 5B). In the presence of 18βGA there was also a significant time-dependent decrease in the amplitude of pacemaker potentials accompanied by contraction and a concomitant decrease in the amplitude of phasic contractions (Figures 4 and 5C,D).

Figure 4.

Tracing illustrating the effect of 18βGA (30 μM for 30 min) on spontaneous electrical and mechanical activity of the guinea-pig proximal renal pelvis. Note that 18βGA induced the apperance of low amplitude action potentials not associated with contractions (marked by asterisks) while concomitantly decreasing the amplitude of action potentials and associated contractions.

Figure 5.

Time course of the effect of 18βGA (30 μM) on frequency of spontaneous action potentials accompanied by contractions (A), frequency of AP (whether or not accompanied by contractions (B), amplitude of AP associated with contraction (C) and amplitude of contraction (D) of the guinea-pig proximal renal pelvis. Each value is mean±s.e.m. of 6–11 experiments. *Significantly different from control P<0.05.

Discussion

Guan et al. (1996) described two effects of 18βGA ascribable to its action as a gap junction inhibitor. They found that, within 30 min from application, 18βGA (40 μM) completely blocked the intercellular dye diffusion in a rat liver epithelial cell line in culture, although the gap junction staining for connexin-43 (C×43) was unaffected at this time (Guan et al., 1996). With a longer (4 h) exposure to the drug a morphological evidence for disassembly of C×43+ gap junctions was obtained, this long term effect being prevented by phosphatases inhibitors (Guan et al., 1996). The authors concluded that the short term effect of 18βGA involves a functional blockade (change in channel structure, changes in the gating of the channels) of intercellular communication via gap junctions, whereas the long term effect involves structural changes probably linked to dephosphorylation of the gap junction channels.

Yamamoto et al. (1998; 1999) reported that 18βGA (40 μM) blocked the electrical coupling between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in guinea-pig mesenteric arterioles within few min from its application. Their findings indicate that, up to 40 μM, 18βGA altered the electrical properties of cells in a manner which is consistent with its ability to disrupt gap junctions and that this concentration of 18βGA does not apparently disturb the function of other ion channels (inward Ca and outward K currents) (Yamamoto et al., 1998; 1999).

We have used 18βGA as a tool to assess the role of intercellular communication via gap junctions in the electromechanical coupling of the guinea-pig upper urinary tract. Considering that the effects of 18βGA developed in full within 30 min from its application, we assume that the observed changes in electromechanical coupling depend upon a functional blockade of intercellular communication via gap junctions similar to the short term effect of 18βGA described by Guan et al. (1996). At 100 μM 18βGA significantly decreased the amplitude of the high K-induced tonic contraction and of the NKA-induced contractions of the ureter, suggesting that non specific effects may occur with this concentration of the drug. Taylor et al. (1998) also reported that 100 μM 18βGA decreased the phenylephrine-induced contractions of rabbit iliac artery probably through a direct effect on smooth muscle.

On the other hand, the effects of 18βGA at 30 μM appear to be consistent with a blockade of the functional syncitium in the upper urinary tract. In interpreting the results presented in this study, it is important to remember that the sucrose gap technique enables to detect multicellular changes in membrane potential and that the amplitude of electrical signals recorded in this way is critically dependent from a good coupling between smooth muscle cells.

The proximal renal pelvis is the site from which the pacemaker potentials governing ureteral peristalsis originate: each pacemaker potential (which ideally may have been fired by a single pacemaker cells) drives the electrical and mechanical activity of the whole specimen. The studies from Lang's group have identified a specialized subpopulation of ‘pacemaker' cells in the proximal renal pelvis which are responsible for generation of this activity (Lang et al., 1998 for review). The decrease in amplitude of pacemaker potentials and accompanying contractions of the renal pelvis produced by 18βGA can be easily accounted for by a progressive blockade of intercellular communication and disruption of the functional syncitium. Notably, in the presence of 18βGA, a number of low amplitude ‘spontaneous' APs appeared which are unable to trigger a contraction. This effect can be explained if assuming that the communication between the dominant pacemaker and certain ‘driven' regions in the renal pelvis were interrupted by 18βGA, enabling the appearance of alternative pacemakers. The effect of 18βGA in the proximal renal pelvis is partly similar to that of nifedipine which likewise diminished the amplitude of pacemaker potentials and eventually suppressed them (Santicioli & Maggi 1997): however, before inducing a total suppression of pacemaker activity, nifedipine did not alter the frequency of pacemaker potentials in the proximal renal pelvis.

The AP of the guinea-pig ureter has been extensively investigated (Kuriyama et al., 1967; Washizu 1966; Shuba 1977; Brading et al. 1983). The presence of multiple spikes on the plateau phase of the AP of the ureter is a peculiar characteristic of this species: the multiple spikes have been recorded with both extra- and intracellular recording techniques as well as from single dispersed ureter cells (Santicioli & Maggi 1998 for review). Washizu (1966) speculated that even in case of intracellular recording from intact ureter, the multiple spikes involve an electrotonic spread of current from neighbouring cells.

Organic Ca channels blockers eliminate all depolarization-evoked electrical and mechanical activities of the guinea-pig ureter, although relatively high concentrations of these drugs are needed to abolish the first spike of the AP, whereas the plateau phase is very sensitive to the inhibitory action of drugs such as nifedipine (Shuba, 1977; Brading et al., 1983). 18βGA rapidly and efficiently eliminated both the first spike of the AP and the multiple spikes superimposed onto the plateau phase. If assuming a selective action of 18βGA on intercellular communication via gap junctions, the present findings strongly support the idea the spikes of the APs recorded from the intact guinea-pig ureter, mediated by recruitment of voltage-sensitive Ca channels, are produced by the rapid and repetitive spread of depolarizing current throughout the preparation via 18βGA-sensitive gap junctions. Interestingly a slow, bell-shaped, AP with a long latency persisted in the presence of 30 μM 18βGA and the accompanying residual contraction ensued before the occurrency of the AP. To our knowledge, a dissociation between electrical and contractile events in response to depolarizing stimuli has not been reported previously in the guinea-pig ureter. Under certain circumstances, the application of caffeine determines a small contraction of the guinea-pig ureter smooth muscle which can be observed in fully depolarized preparations and likely reflects Ca mobilization from an internal store (Burdyga et al., 1995). However, the residual contractile response observed in response to EFS in the presence of 30 μM 18βGA was abolished by nifedipine indicating that no qualitative switch in the mechanisms of electromechanical coupling had occurred under the action of 18βGA. It is possible that the temporal dissociation between the electrical and mechanical responses to EFS recorded in the presence of 30 μM 18βGA is more apparent (linked to the recording technique) than substantial. Since the sucrose gap technique detects multicellular electrical events having a certain degree of propagation within the specimen, we intepret these observations as indication that gap junction blockade produced by 30 μM 18βGA was incomplete. In this case electrical events which are too small to be detected by the sucrose gap technique could still be able to induce local contractile events which fuse together to induce a detectable contractile response. In this respect, it is worth noting that, despite a 50% reduction in the amplitude of EFS-evoked contraction in the presence of 30 μM 18βGA, the duration of contraction was not appreciably affected by the drug, indicating that the duration of the contraction-relaxation cycle of the ureter smooth muscle was actually longer in the presence than in the absence of 18βGA. It is also interesting to note that a number of small and desynchronized (presumably ‘local') contractile events were evident in the response to NKA in the presence of 18βGA (Figure 3): however, this behaviour was not observed in the presence of 18βGA for the contractile response to EFS since the contractile even remained monophasic even in the presence of 18βGA.

It is interesting to compare the effect of 18βGA on EFS- and NKA-evoked APs in the guinea-pig ureter. In the former case, discussed above, a brief depolarizing stimulus is applied which directly leads to recruitment of voltage-sensitive Ca channels and spreads through the preparation to induce a phasic contraction. In the case of NKA, the excitatory stimulus is more prolonged and recruitment of voltage-sensitive Ca channels occurs indirectly, through the occupancy of a G-protein coupled tachykinin NK2 receptor (Patacchini et al., 1998) and subsequent activation of several signalling systems. In this case the recruitment of voltage-sensitive Ca channels occurs indirectly, via a nifedipine-resistant depolarization which may involve suppression of outward K currents, the activation of Ca-dependent Cl current and/or activation of nonselective cation channels (see Patacchini et al., 1998 for discussion). As a matter of fact, the application of exogenous NKA prolonged the duration of APs evoked by EFS, suggesting a suppressant effect on repolarizing K currents (Patacchini et al., 1998; see also Muraki et al., 1994). An inhibitory effect of NKA on K currents could be an important factor to account for the changes in the response to this neuropeptide observed in the presence of 18βGA. In fact while decreasing the amplitude of NKA-evoked APs, 18βGA markedly prolonged the contractile response to NKA and several small phasic contractions apparently fused together to induce a tonic type contraction. The total area of NKA-evoked contraction was actually increased by 18βGA despite the marked inhibition of electrical activity further supporting the interpretation that 18βGA had induced a switch from a single-unit to a multi-unit behaviour of the preparation, consistent with a blockade of intercellular communication via gap junctions.

In conclusion the present findings provide evidence that 18βGA, up to 30 μM is an useful tool for studying the role of gap junctions in excitation-contraction coupling in smooth muscle. The degree of gap junction blockade produced by this concentration of the drug is probably incomplete, as already suggested and discussed by Yamamoto et al. (1998; 1999). At higher concentrations 18βGA possesses nonspecific effects on smooth muscle excitation-contraction coupling.

Abbreviations

- AP

action potentials

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- 18βGA

18β-glycyrrhetinic acid

- NKA

neurokinin A

- s.e.m.

standard error of the mean.

References

- ARTEMENKO D.P., BURY V.A., VLADIMIROVA I.A., SHUBA M.F. Modification of the single sucrose-gap method. Physiol. Zhurn. 1982;28:374–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOZLER E. The activity of the pacemaker previous to the discharge of a muscular impulse. Am. J. Physiol. 1942a;136:543–552. [Google Scholar]

- BOZLER E. The action potentials accompanying conducted responses in visceral smooth muscles. Am. J. Physiol. 1942b;136:552–560. [Google Scholar]

- BRADING A.F., BURDYGA TH.V., SCRIPNYUK Z.D. The effects of papaverine on the electrical and mechanical activity of the guinea-pig ureter. J. Physiol. 1983;334:79–89. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURDYGA TH.V., TAGGART M.J., WRAY S. Major difference between rat and guinea-pig ureter in the ability of agonists and caffeine to release Ca and influence force. J. Physiol. 1995;489:327–335. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIDSON J.S., BAUMGARTEN I.M., HARLEY E.H. Reversible inhibition of intercellular junctional communication by glycyrrhetinic acid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1986;134:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GABELLA G. Structure of smooth muscles 1994111Springer Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg; 3–34.in Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. L. Szekeres and J.Gy. Papp (eds) [Google Scholar]

- GUAN X., WILSON S., SCHLENDER K.K., RUCH R.J. Gap junction disassembly and connexin 43 depihosphorylation induced by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid. Mol. Carcinogenesis. 1996;16:157–164. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199607)16:3<157::AID-MC6>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOYLE C.H.V. A modified single sucrose gap - junction potentials and electrotonic potentials in gastrointestinal smooth muscle. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1987;18:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(87)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURIYAMA H., OSA T., TOIDA N. Membrane properties of the smooth muscle of guinea-pig ureter. J. Physiol. 1967;191:225–235. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANG R.J., EXINTARIS B., TEELE M.E., HARVEY J., KLEMM M.F. Electrical basis of peristalsis in the mammalian upper urinary tract. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1998;25:310–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOEWENSTEIN W.R. The cell-cell channel of gap junction. Cell. 1987;48:725–726. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGGI C.A., SANTICIOLI P., GIULIANI S. Protein kinase A inhibitors selectively inhibit the tonic contraction of the guinea-pig ureter to high potassium. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:341–348. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAKI K., IMAIZUMI Y., WATANABE M. Effects of noradrenaline on membrane currents and action potential shape in smooth muscle cells from guinea-pig ureter. J. Physiol. 1994;481:617–627. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATACCHINI R., SANTICIOLI P., ZAGORODNYUK V., LAZZERI M., TURINI D., MAGGI C.A. Excitatory motor and electrical effects produced by tachykinins in the human and guinea-pig isolated ureter and guinea-pig renal pelvis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:987–996. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTICIOLI P., MAGGI C.A. Pharmacological modulation of electromechanical coupling in the proximal and distal regions of the guinea-pig renal pelvis. J. Autonom. Pharmacol. 1997;17:43–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.1997.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANTICIOLI P., MAGGI C.A. Myogenic and neurogenic factors in the control of pyeloureteral motility and ureteral peristalsis. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:683–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUBA M.F. The effect of sodium-free and potassium-free solutions ionic current inhibitors and ouabain on electrophysiological properties of smooth muscle of guinea-pig ureter. J. Physiol. 1977;264:837–851. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR H.J., CHAYTOR A.T., EVANS W.H., GRIFFITH T.M. Inhibition of the gap junctional component of endothelium-dependent relaxations in rabbit iliac artery by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;135:1–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WASHIZU Y. Grouped discharges in ureter muscle. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1966;19:713–728. [Google Scholar]

- WILLECKE K., HENNEMANN H., DAHL E., JUNGBLUTH S., HEYNKES R. The diversity of connexin genes encoding gap junctional proteins. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 1991;56:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO Y., FUKUDA H., NAKAHIRA Y., SUZUKI H. Blockade by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid of intercellular electrical coupling in guinea-pig arterioles. J. Physiol. 1998;511:501–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.501bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO Y., IMAEDA K., SUZUKI H. Endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and intercellular electrical coupling in guinea-pig mesenteric arterioles. J. Physiol. 1999;514:505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.505ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]