Abstract

A single dose of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) has previously been shown to be neuroprotective in the gerbil model of global ischaemia.

In gerbils, clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1) injection produced a rapid appearance (peak within 5 min) of drug in plasma and brain and similar clearance (plasma t1/2: 40 min) from both tissues. The peak brain concentration (226±56 nmol g−1) was 40% higher than plasma.

One major metabolite, 5-(1-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro)-4-methylthiazole (NLA-715) and two minor metabolites 5-(1-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole (NLA-272) and 5-acetyl-4-methylthiazole (NLA-511) were detected in plasma and brain.

Evidence suggested that clomethiazole is metabolized directly to both NLA-715 and NLA-272.

Injection of NLA-715, NLA-272 or NLA-511 (each at 600 μmol kg−1) produced brain concentrations respectively 2.2, 38 and 92 times greater than seen after clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1).

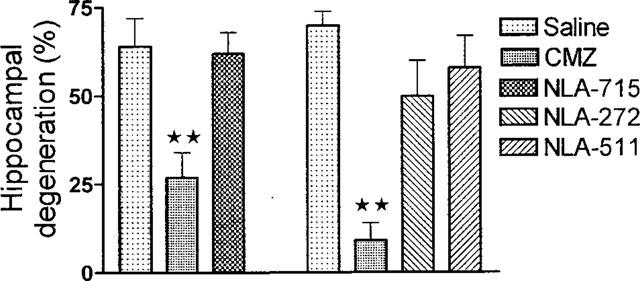

Clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1) injected 60 min after a 5 min bilateral carotid artery occlusion in gerbils attenuated the ischaemia-induced degeneration of the hippocampus by approximately 70%. The metabolites were not neuroprotective at this dose.

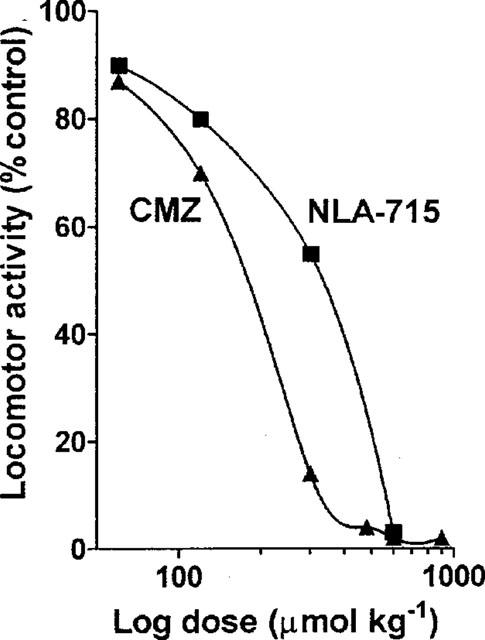

In mice, clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1) produced peak plasma and brain concentrations approximately 100% higher than in gerbils, drug concentrations in several brain regions were similar but 35% higher than plasma. Clomethiazole (ED50: 180 μmol kg−1) and NLA-715 (ED50: 240 μmol kg−1) inhibited spontaneous locomotor activity. The other metabolites were not sedative (ED50 >600 μmol kg−1).

These data suggest that the neuroprotective action of clomethiazole results from an action of the parent compound and that NLA-715 contributes to the sedative activity of the drug.

Keywords: Clomethiazole, clomethiazole metabolites, neuroprotection, global ischaemia, sedation, hippocampal degeneration, neurodegeneration, stroke

Introduction

There is now substantial evidence that clomethiazole (BAN: chlormethiazole; INN: clomethiazole) is neuroprotective in a variety of experimental models of ischaemic stroke. It has been shown to be effective in the gerbil global model of hypoxic ischaemia (Cross et al., 1991; 1995; Baldwin et al., 1993; Shuaib et al., 1995; Liang et al., 1997) and also decreases damage in the rat photochemical ischaemia model (Snape et al., 1993; Baldwin et al., 1994). Clomethiazole is neuroprotective in both permanent and reversible focal models of middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat (Sydserff et al., 1995a,1995b), and has recently been shown to attenuate the pathological consequences of a permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in the marmoset; the drug decreasing both volume of infarction and the resultant behavioural abnormalities (Marshall et al., 1999). These data have been reviewed in detail elsewhere (Green, 1998).

In a recent placebo-controlled trial in 1360 acute stroke patients, clomethiazole (Zendra®) has also been shown to produce significant benefit in a sizeable subgroup of patients whose clinical description suggested a large stroke. The result corresponded to a 37% improvement over the placebo response (Wahlgren et al., 1999). In consequence a prospective Phase III trial is now underway in North America.

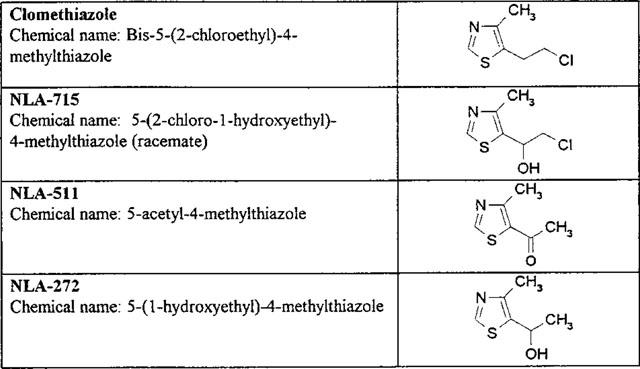

In humans, clomethiazole has been reported to be extensively metabolized, with less than 1% being found unchanged in the urine (see Dollery, 1991). However, many of the metabolites reported to occur in humans (Dollery, 1991) were identified many years ago by methods that would not now be considered reliable. A major metabolic route has been suggested to be hydroxylation to 5-(2-chloro-1-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole [Company code: NLA-715], with greater than 15% being found in urine (Ende et al., 1979). NLA-715 was suggested to be metabolized further to 5-(1-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole [NLA-272] and 5-acetyl-4-methylthiazole [NLA-511] and it was also suggested (Dollery, 1991) that clomethiazole could also be metabolized directly to NLA-272 (see Figure 1 for structures).

Figure 1.

The structures, codes and chemical names of clomethiazole and its metabolites studied in the investigation.

There is extensive evidence for the neuroprotective properties of clomethiazole in the gerbil (see Green, 1998) and neuroprotective doses are similar in both this model and the transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model (Cross & Green, unpublished). We have now therefore investigated whether metabolites can be identified in the plasma and brain of the gerbil and whether any metabolites identified have neuroprotective properties. In addition we have examined the plasma and brain concentrations of clomethiazole in mice following its peripheral administration and also investigated whether clomethiazole and its metabolites are sedative in this species. Mice were used in the study because they exhibit high levels of locomotor activity on exposure to a novel environment and therefore provide a sensitive measure of drug-induced sedative activity.

Methods

Animals

Male Mongolian gerbils (B & K Universal, Hull, U.K.) weighing 60–80 g were housed in groups of eight, unless they were subjected to global ischaemia when they were housed singly following surgery. Male C57/6J black mice (Harlan U.K. Ltd, Oxon, U.K.) weighing 25–30 g were also used and were housed in groups of eight. All animals were kept in conditions of controlled temperature (19–21°C) and lighting (12 h light/12 h dark, lights on 0700 h–1900 h) and allowed free access to food (RM1, Special Diet Services Ltd, Essex, U.K.) and tap water.

Drugs and reagents

NLA-272, NLA-511 and NLA-715 were all synthesised at the Astra Neuroscience Research Unit, London, U.K. Clomethiazole edisilate was synthesized at Astra Production Chemicals AB, Södertälje, Sweden. Other agents used in this study were obtained from the following sources: Saffan (Alphaxalone plus Alphadalone; Glaxo Vet Ltd, Uxbridge, U.K.), Sagatal (Sodium pentobarbitone; May & Baker Ltd, Dagenham, U.K.), formalin, sucrose, sodium chloride (Merck Ltd, Poole, U.K.). Clomethiazole and the metabolites were dissolved in saline (0.9% w v−1 NaCl in distilled water) and administered in a volume of 4 ml kg−1 (gerbils) and 10 ml kg−1 (mice).

Measurement of clomethiazole concentrations in plasma and brain

Plasma was obtained by centrifuging trunk blood samples at 300 r.p.m. for 30 min. Plasma samples were extracted as follows: 100 μl plasma was added to 515 μl perchloric acid (200 mM) and centrifuged at 13,000 r.p.m. for 15 min. The supernatant was removed and assayed for clomethiazole using high performance liquid chromatography by an adaptation of the method of Kim & Khanna (1983). Briefly, samples were injected onto a reversed phase analytical column (25×4.6 mm, 5 mm ODS, Hypersil, Technicol, U.K.) by an autosampler with a 100 μl injection loop. The mobile phase (flow rate 1.2 ml min−1) comprised 70% KH2PO4 (25 mM) plus 30% acetonitrile (final pH 4.6) and was filtered and degassed before use. Analysates were detected with a UV detector (absorbance: 254 nm). The system was connected to a computer-integrator (Axiom, U.K.) which analysed the chromatograms according to peak area. Using this system clomethizole had a retention time of 10–12 min.

For analysis of the clomethiazole concentration in brain tissue, the brain was homogenized in H2O with an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 r.p.m. for 15 min and the supernatant treated in the same way as plasma.

Measurement of NLA-272, NLA-511 and NLA-715 concentrations in plasma and brain

Methods have recently been developed for the measurement of clomethiazole metabolites in mammalian tissues, with mass spectrometry and h.p.l.c. retention times being used for absolute identification (Andersson & Gabrielsson, unpublished). The h.p.l.c. technique was used in the current study, and is now briefly described. Plasma was obtained as described above. NLA-715, NLA-272 or NLA-511 were extracted from plasma samples by solid phase extraction using minicolumns with C8 1 mg ml−1 sorbant (International Sorbent Technology) and vacuum manifold. C8 columns were first wet with 2 ml methanol, then equilibrated with 2 ml water (HPLC grade). 50 ml plasma sample+750 ml water were applied to column. The column was washed with 2 ml water followed by elution with 500 ml 25 mM KH2PO4, 30% acetonitrile pH 3.5. The eluate was transferred to autosampler vials and assayed for NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511 using h.p.l.c. Samples were injected onto a reversed phase analytical column (Phenomenex 250×4.6 mm, 5 mm Ultracarb C8 (base deactivated), Technicol, U.K.) by an autosampler with a 20 ml injection loop. The mobile phase (flow rate 1 ml min−1) controlled by a LKB 2150 pump comprised 75% KH2PO4 (25 mM), 15% acetonitrile and 10% methanol (final pH 3.5) and was filtered and degassed before use. Analysates were detected with a UV detector (absorbance: 250 nm). The system was connected to a computer-integrator as above. Brain tissue was prepared for analysis as described for clomethiazole measurement and the homogenate treated as plasma.

Induction of ischaemia and drug administration

Animals were anaesthetized using Saffan (alphaxalone 166 μmol kg−1 i.p. plus alphadalone 47 μmol kg−1 i.p.), and placed on a heating mat and under heating lamps to maintain body temperature (monitored by rectal probe) at 37.5±1.0°C for at least 2 h post-ischaemia. Transient forebrain ischaemia was then induced by bilateral carotid artery occlusion (Cross et al., 1991; 1995). Following ischaemia, the wound was sutured and animals allowed to recover on a heating mat until drug administration.

In the first experiment, animals received either a single i.p. injection of vehicle, clomethiazole (600 μml kg−1) or NLA-715 (600 μmol kg−1) 60 min post-ischaemia. In the second experiment, animals received either a single injection of vehicle, clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1), NLA-272 (600 μmol kg−1) or NLA-511 (600 μmol kg−1), again 60 min post-ischaemia.

Histology and measurement of neuronal damage

Animals were killed 4 days post-ischaemia. The animals were anaesthetized with Sagatal (1.73 μmol kg−1 i.p.) and transcardiac perfusion performed, using ∼30 ml of 5% sucrose in formalin solution at room temperature. The brains were removed and stored at 4°C in 30% sucrose in formalin solution for at least 24 h. Brains were frozen and coronal sections of 20 μm thickness taken through the hippocampal region using a cryostat. These sections were stained using cresyl violet acetate (Sigma Chemical Co., U.K.) as described by Cross et al. (1991). Sections from each brain taken at the level of the hippocampus, corresponding to level 1600 μm caudal to bregma (according to the atlas of Loskota et al., 1973) were used to assess the extent of damage. The extent of neurodegeneration was measured using a computerized image analysis package (Global Lab Image; Data Translation Ltd, U.S.A.). The length of the CA1/CA2 region containing degenerated neurones was expressed as a percentage of the entire CA1/CA2 region. All assessments of histological sections were made by an observer who was unaware of the drug treatments.

Drug administration and behavioural testing

Mice (n=4 per group) were administered either drug or vehicle 10 min prior to testing. Locomotor activity was assessed using an automated open field system (PMS Instruments Ltd. Maidenhead, Berks, U.K.) consisting of a four cage animal activity monitoring system. Movement was detected by the interruption of an array of 32 infrared beams produced by photocells mounted horizontally in a frame which surrounded the perimeter of each box. Locomotor activity data was acquired by an AMB analyser (IPC Instruments, Berks, U.K.). Each animal was placed individually in one of the boxes and locomotor activity measured continuously for 10 min. Results were plotted as mean (±s.e.mean) total locomotor activity for the whole 10 min test period and expressed as a percentage of control activity, allowing calculation of the dose required to produce a 50% decrease in locomotor activity (ED50 locomotor activity).

Results

Plasma and brain clomethiazole concentrations in gerbils following clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.)

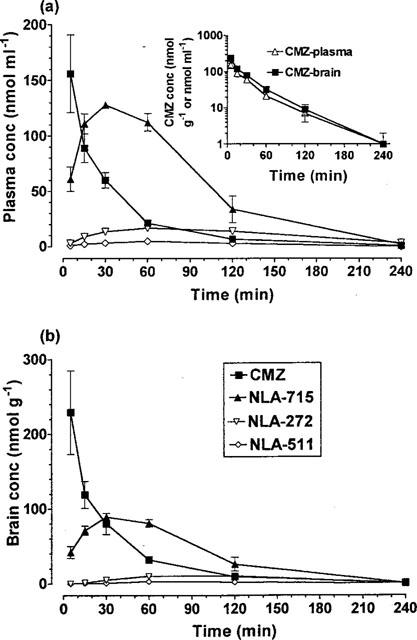

Following an injection of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) the plasma drug concentration peaked within 5 min, reaching 155 nmol ml−1 and declined rapidly thereafter (Figure 2a). The log concentration-time response decline was almost linear with a t½ of 40 min (Figure 2). The brain clomethiazole concentration also peaked within 5 min, the concentration being 43% higher than blood (Figure 2b). Thereafter is decreased similarly in both tissues (Figure 2) and was undetectable 4 h after administration.

Figure 2.

The concentration of clomethiazole (CMZ) and its metabolites NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511 in (a) plasma (top graph) and (b) brain (bottom graph) following a dose of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to gerbils. Results shown as mean±s.e.mean of n=4–6 observations. Inset graph: Decline in the log concentration of clomethiazole (CMZ) in plasma and brain following a dose of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to gerbils. Redrawn from data in main figures.

The concentration of clomethiazole metabolites in plasma and brain after clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) administration to gerbils

The three metabolites (NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511) identified in gerbil plasma following a dose of clomethiazole were quantified in both plasma and brain following a single injection of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1). In both plasma and brain only NLA-715 was detected in substantial amount following clomethiazole, although both NLA-272 and NLA-511 also were measurable for at least 120 min post-injection (Figure 2).

Plasma and brain NLA-715 concentrations in gerbils following NLA-715 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.)

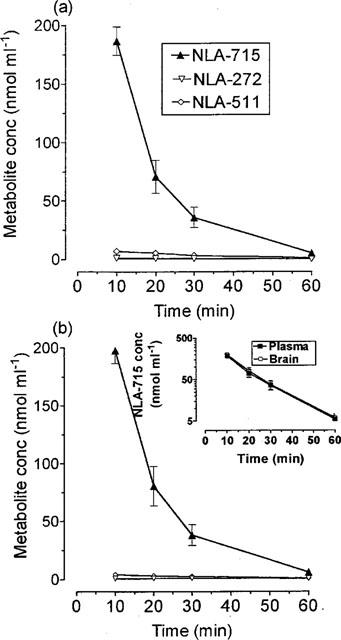

Following a single injection of NLA-715 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) there was a rapid rise in the concentration of this compound in both plasma (Figure 3a) and brain (Figure 3b). The concentration of NLA-715 was essentially the same in plasma and brain and the cerebral concentration was at least two times that seen after clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) injection. The drug was eliminated from both tissues at the same rate (Figure 3, inset graph). The concentrations of NLA-272 and NLA-511 were only just above the level of detection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The concentration of NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511 in plasma and brain following administration of NLA-715 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to gerbils. Results shown as mean±s.e.mean of n=4–6 observations. Insert graph shows the decline in the log concentration of compounds in plasma and brain following a dose of NLA-715.

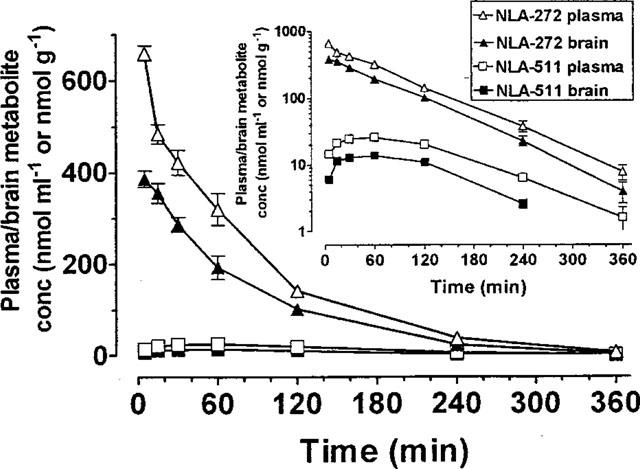

Plasma and brain NLA-272 and NLA-511 concentrations in gerbils following NLA-272 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) or NLA-511 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.)

Following an injection of NLA-272 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) the plasma and brain drug concentration peaked within 5 min, decreasing linearly and in parallel thereafter (Figure 4), the t½ being approximately 60 min (Figure 4). The cerebral concentration was more than 400 times the concentration seen after a single injection of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1). NLA-511 was also detected in both plasma and brain the peak occurring later than that of NLA-272 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The concentration of NLA-272 and NLA-511 in plasma and brain following administration of NLA-272 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to gerbils. Results shown as mean±s.e.mean of n=4–6 observations. Insert graph shows the decline in the log concentration of compounds in plasma and brain following a dose of NLA-272.

Following an injection of NLA-511 (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) the plasma drug concentration also peaked within 5 min and then declined linearly, with a t½ of 65 min (data not shown). The brain NLA-511 concentration peaked within 15 min at a concentration some 92 times that seen after an injection of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) and declined in parallel with the plasma (data not shown).

Studies on the neuroprotective properties of NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511 in gerbils

In the first experiment the possible neuroprotective property of NLA-715 was compared with clomethiazole, both being given at a dose of 600 μmol kg−1. Clomethiazole was an effective neuroprotective agent, while NLA-715 showed no effect (Figure 5). In the second study clomethiazole again protected against ischaemia-induced damage to the hippocampus, while NLA-272 and NLA-511 (both at 600 μmol kg−1) were without effect (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The effect of clomethiazole (CMZ), NLA-715, NLA-272 and NLA-511 on hippocampal CA1/CA2 degeneration following 5 min transient ischaemia in the gerbil. The compounds were given 60 min after the ischaemic episode. Columns represent the mean damage with ±s.e.mean shown by bar, n=8–12. **Indicates difference from saline injected control group P<0.01. Data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and individual group differences with post hoc Dunnett's test.

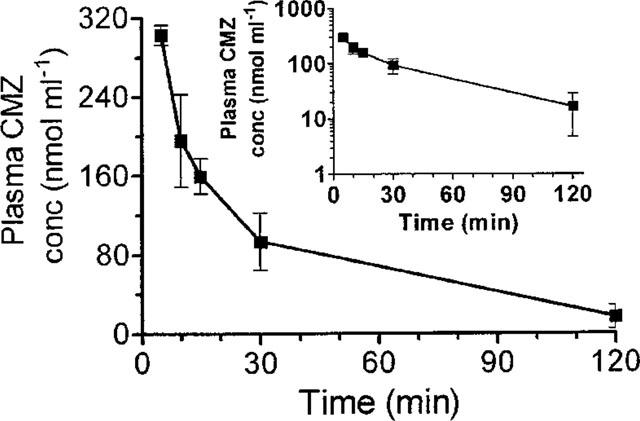

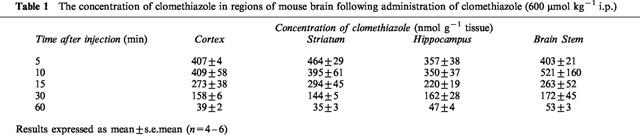

Plasma and brain concentration of clomethiazole following administration of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to mice

The plasma concentration of clomethiazole peaked within 5 min after injection declining rapidly thereafter in a t½ of 20 min (Figure 6). A similarly rapid peak and decline was observed in cerebral tissue (Table 1). The peak concentration in both tissues was around twice that seen in gerbil tissues following this dose. Whilst the distribution of the drug in the various regions of the brain was similar, the hippocampus had the lowest drug concentration and the striatum the highest during the first 15 min post injection (Table 1).

Figure 6.

The concentration of clomethiazole (CMZ) in plasma following an injection of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.) to the mouse. Results shown as mean±s.e.mean of n=4 observations.

Table 1.

The concentration of clomethiazole in regions of mouse brain following administration of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1 i.p.)

Effect of clomethiazole and metabolites on sedation in the mouse

Both clomethiazole and NLA-715 inhibited spontaneous locomotor activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7) allowing ED50 values to be calculated (clomethiazole: 180 mol kg−1, NLA-715: 240 mol kg−1). Neither NLA-272 or NLA-511 had a significant effect at doses up to 600 μmol kg−1.

Figure 7.

The per cent inhibition of locomotor activity in mice following various doses of clomethiazole (CMZ) or NLA-715. Results show mean value of n=4 observations at each dose.

Discussion

Following a single intraperitoneal injection of clomethiazole to the gerbil there was a rapid appearance of the compound in the blood and brain. The peak plasma concentration was similar to that reported previously and the plasma half life (40 min) was also similar to the value (25 min) observed by Cross et al. (1995). The disappearance of clomethiazole in the brain paralleled its disappearance in plasma, but the concentration was approximately 40% higher at all times measured. We previously observed (Cross et al., 1995) that following a 24 h infusion of the drug, the brain concentration was similarly 40% higher than that in plasma. The current study has now shown that the cerebral concentration in mice is also 35% higher than plasma levels and declines in parallel with plasma. These data suggest that clomethiazole does not accumulate in cerebral tissue and that the plasma concentration can normally be used as a reflection of the cerebral concentration. It also demonstrates that the compound is normally present at greater concentration in the brain than plasma, an attractive property in a drug to be used as a neuroprotective agent for the treatment of stroke.

The major metabolite rapidly detected in plasma after an injection of clomethiazole was NLA-715, indicating that hydroxylation is a major initial degradative step in the gerbil. NLA-272 and NLA-511 were also detected at low concentration. All three metabolites were also detected in the brain, although at a lower concentration than in plasma and all followed a similar time course of disappearance to that seen in plasma.

Injection of NLA-715 failed to produce significant concentrations of either NLA-272 or NLA-511, indicating that NLA-715 is probably not metabolized directly to NLA-272 and thence to NLA-511 as previously stated (Dollery, 1991), at least in gerbils, and that NLA-272 is probably formed directly from clomethiazole.

In two separate experiments, administration to gerbils of clomethiazole (600 μmol kg−1) 60 min after an ischaemic episode resulted in substantial neuroprotection against damage to the hippocampus, confirming several other reports on the protective properties of this compound in the gerbil two-vessel occlusion model of global ischaemia (Cross et al., 1991; 1995; Baldwin et al., 1994; Shuaib et al., 1995; Liang et al., 1997). The only metabolite present in the brain in substantial quantity following clomethiazole is NLA-715. The brain concentration of this compound following its peripheral injection was approximately twice than that seen after clomethiazole administration. Nevertheless there was no indication of any neuroprotective activity. We therefore feel confident in suggesting that this metabolite is not neuroprotective. The concentration of the other two metabolites was also high in the brain following their i.p. injection so their lack of protective activity after their peripheral administration cannot be ascribed to poor brain penetration. It can therefore be concluded that none of the metabolites are neuroprotective.

We also examined whether the metabolites had sedative properties. Mice were used because they exhibit high levels of locomotor activity on exposure to a novel environment and therefore provide a sensitive measure of drug-induced sedation. However it was first necessary to confirm that a similar ratio of brain to plasma concentration occurred in mouse and gerbil following an injection of clomethiazole. Results showed this to be the case, although the tissue concentration of the drug in the mouse was approximately twice that seen in the gerbil following the same dose of drug. This part of the study also demonstrated that while clomethiazole had a similar concentration in all brain regions examined, the hippocampus had the lowest concentration and striatum the highest during the first 15 min after drug administration.

The ED50 for the sedative effect of clomethiazole in the mouse was 180 μmol kg−1 which is considerably higher than the value in the rat (ED50: 30 μmol kg−1; Green et al., 1996). NLA-715 also had significantly sedative activity (ED50: 240 mol kg−1), which, given the high concentration of this metabolite present in the brain following clomethiazole, almost certainly contributes to the sedation occurring after injection of the parent compound. Neither of the other metabolites examined was sedative.

In conclusion, these data demonstrate that in gerbils the neuroprotective activity of clomethiazole results from an action of the parent compound, rather than active metabolites, but that the major metabolite NLA-715 may contribute to the sedation that can occur after clomethiazole.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lars B. Nilsson for analysis of some of the plasma and brain samples.

Abbreviations

- CMZ

clomethiazole

- NLA-272

5-(1-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole

- NLA-511

5-acetyl-4-methylthiazole

- NLA-715

5-(1-hydroxyethyl-2-chloro)-4-methylthiazole

References

- BALDWIN H.A., JONES J.A., CROSS A.J., GREEN A.R. Histological, biochemical and behavioural evidence for the neuroprotective action of chlormethiazole following prolonged carotid artery occlusion. Neurodegeneration. 1993;2:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- BALDWIN H.A., WILLIAMS J.L., SNARES M., FERREIRA T., CROSS A.J., GREEN A.R. Attenuation by chlormethiazole administration of the rise in extracellular amino acids following focal ischaemia in the cerebral cortex of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;112:188–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROSS A.J., JONES J.A., BALDWIN H.A., GREEN A.R. Neuroprotective activity of chlormethiazole following transient forebrain ischaemia in the gerbil. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;104:406–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROSS A.J., JONES J.A., SNARES M., JOSTELL K-G., BREDBERG U., GREEN A.R. The protective action of chlormethiazole against ischaemia-induced neurodegeneration in gerbils when infused at doses having little sedative or anticonvulsant activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1625–1630. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLLERY C. Therapeutic Drugs. Vol I. Churchill Livingstone, London; 1991. pp. C184–C188. [Google Scholar]

- ENDE E., SPITELLER G., REMBERG G., HEIPERTS R. Urinary metabolites of chlormethiazole. Arzneimittel Forsch. 1979;29:1655–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN A.R. Clomethiazole (Zendra®) in acute ischemic stroke: basic pharmacology and biochemistry and clinical efficacy. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998;80:123–147. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN A.R., MISRA A., MURRAY T.K., SNAPE M.F., CROSS A.J. A behavioural and neurochemical study in rats of the pharmacology of loreclezole, a novel allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1243–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM C., KHANNA J.M. Determination of chlormethiazole in blood by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Liquid Chromatogr. 1983;6:907–916. [Google Scholar]

- LIANG S.P., KANTHAN R., SHUAIB A., WISHART T. Effects of clomethiazole on radial-arm maze performance following global forebrain ischaemia in gerbils. Brain Res. 1997;751:189–195. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOSKOTA W.J., LOMAX P., VERITY M.A. Ann Arbor Science Publishers Inc., Michigan, U.S.A; 1973. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Mongolian Gerbil Brain (Meriones unguiculatus) [Google Scholar]

- MARSHALL J.W.B., CROSS A.J., RIDLEY R.M. Functional benefit from clomethiazole treatment after focal cerebral ischemia in a non human primate species. Exp. Neurol. 1999;156:121–129. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUAIB A., IJAZ S., KANTHAN R. Clomethiazole protects the brain in transient forebrain ischemia when used up to 4 h after the insult. Neurosci. Letts. 1995;197:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11934-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNAPE M.F., BALDWIN H.A., CROSS A.J., GREEN A.R. The effects of chlormethiazole and nimodipine on cortical infarct area after focal ischaemia in the rat. Neuroscience. 1993;53:837–844. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90628-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SYDSERFF S.G., CROSS A.J., GREEN A.R. The neuroprotective effect of chlormethiazole on ischaemic neuronal damage following permanent middle cerebral artery ischaemia in the rat. Neurodegeneration. 1995a;4:323–328. doi: 10.1016/1055-8330(95)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SYDSERFF S.G., CROSS A.J., WEST K.J., GREEN A.R. The effect of chlormethiazole on neuronal damage in a model of transient focal ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995b;114:1631–1635. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAHLGREN N.G., RANASINTHA K.W., ROSOLACCI T., FRANCKE C.L. , VAN ERVEN P.M.M., ASHWOOD T., CLAESSON L. , FOR THE CLASS STUDY GROUP Clomethiazole acute stroke study (CLASS). Results of a randomized, controlled trial of clomethiazole versus placebo in 1360 acute stroke patients. Stroke. 1999;30:21–28. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]