Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate a role for Epithelial Sodium Channels (ENaCs) in the mechanical activation of low-threshold vagal afferent nerve terminals in the guinea-pig trachea/bronchus.

Using extracellular single-unit recording techniques, we found that the ENaC blocker amiloride, and its analogues dimethylamiloride and benzamil caused a reduction in the mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent fibres.

Amiloride and it analogues also reduced the sensitivity of afferent fibres to electrical stimulation such that greater stimulation voltages were required to induce action potentials from their peripheral terminals within the trachea/bronchus.

The relative potencies of these compounds for inhibiting electrical excitability of afferent nerves were similar to that observed for inhibition of mechanical stimulation (dimethylamiloride≈#38;benzamil>amiloride). This rank order of potency is incompatible with the known rank order of potency for blockade of ENaCs (benzamil>amiloride>>dimethylamiloride).

As voltage-gated sodium channels play an important role in determining the electrical excitability of neurons, we used whole-cell patch recordings of nodose neuron cell bodies to investigate the possibility that amiloride analogues caused blockade of these channels. At the concentration required to inhibit mechanical activation of vagal nodose afferent fibres (100 μM), benzamil caused significant inhibition of voltage-gated sodium currents in neuronal cell bodies acutely isolated from guinea-pig nodose ganglia.

Combined, our findings suggest that amiloride and its analogues did not selectively block mechanotransduction in airway afferent neurons, but rather they reduced neuronal excitability, possibly by inhibiting voltage-gated sodium currents.

Keywords: Mechanotransduction, amiloride, benzamil, dimethylamiloride, sensory nerves, nodose ganglion, airway, vagus nerve, primary afferent neuron

Introduction

Ion channels involved in mechanotransduction in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans have extensive sequence homology with the superfamily of proteins that includes Epithelial Sodium Channels (ENaCs) (Garcia-Anoveros & Corey, 1997). Consistent with a role for ENaCs in mechanotransduction, the alpha subunit of ENaC exhibits pressure-induced ion gating when expressed in fibroblasts (Kizer et al., 1997) or inserted into lipid bilayers (Awayda et al., 1995). Recent studies from several laboratories have led to the hypothesis that members of the ENaC superfamily of ion channels may be involved in mechanotransduction in vertebrate primary afferent nerves. For example, a genetic knockout of the BNC1 gene, which encodes a sodium channel belonging to the ENaC superfamily, reduced the response of rapidly adapting mouse skin mechanosensors (Price et al., 2000) and mRNAs encoding ENaC subunits were found in putative mechanosensory neurons from nodose (Drummond et al., 1998), trigeminal (Fricke et al., 2000), or dorsal root (Drummond et al., 2000) ganglia. Moreover, nonselective ENaC channel blockers, such as amiloride and its analogue benzamil, reduced mechanically-evoked ion currents (McCarter et al., 1999) and inhibited mechanically-evoked increases of intracellular Ca2+ (Drummond et al., 1998; Gschossmann et al., 2000) at the level of the afferent nerve cell body. In addition to affects on mechanically-gated ionic currents measured at the cell soma, amiloride or benzamil also inhibit pressure-evoked baroreceptor afferent nerve activity (Drummond et al., 1998) and renal afferent nerve activity evoked by increases in renal pelvic pressure (Kopp et al., 1998). Collectively, these data support the hypothesis that ENaCs are directly involved in the transduction of mechanical force to the generator potential in primary afferent nerve endings.

An alternative hypothesis of mechanotransduction in the viscera is that ion channels in the epithelium of hollow organs are gated by distension of the organ, leading to stretch-induced release of mediators from the epithelium, which in turn act on afferent nerve terminals within the tissue leading to action potential discharge. A novel role for ATP in this type of indirect activation of afferent fibres has recently been proposed (Burnstock, 1999). Consistent with this model, mechanical stimulation of airway epithelial cells induces them to release ATP (Grygorczyk & Hanrahan, 1997; Homolya et al., 2000) and a subpopulation of afferent neurons in the airways express P2X3 purinoceptors (Brouns et al., 2000) and respond to exogenous ATP (Pelleg & Hurt, 1996).

The guinea-pig isolated, innervated airway preparation is a useful model to study mechanical transduction in vagal afferent nerves (McAlexander et al., 1999). Both high-threshold (nociceptive-like) fibres and low-threshold mechanotransducers can be studied in this model (Riccio et al., 1996). The aim of the present study was to investigate a role for ENaCs and the epithelium in the mechanical activation of low-threshold vagal afferent nerve terminals in the guinea-pig trachea/bronchus. Our data show that although amiloride and related compounds effectively inhibit mechanical activation of airway primary afferent nerve endings, this is not a consequence of selective inhibition of ion flow through ENaCs. Rather, the data suggest that this family of compounds inhibited mechanically-induced impulse generation in vagal afferent nerves by inhibiting voltage-gated sodium currents. Our findings also support the hypothesis that epithelial cells are not necessary for mechanotransduction in airway afferent nerves.

Methods

Extracellular electrophysiological recording

Male Hartley guinea-pigs (200–400 g) were killed by asphyxiation with CO2 and exsanguinated. The trachea and primary bronchi with intact right-side extrinsic innervation including nodose ganglia, were removed and placed in a dissecting dish containing Krebs bicarbonate buffer solution (KBS) composed of (in mM): NaCl 118; KCl 5.4; NaH2PO4 1.0; MgSO4 1.2; CaCl2 1.9; NaHCO3 25.0; dextrose 11.1. Connective tissue was carefully trimmed away from the trachea, larynx and right bronchus leaving the vagus, superior laryngeal, and recurrent nerves, including nodose ganglia intact. A longitudinal cut was made to open the larynx, trachea and bronchus along the ventral surface. Airways were then pinned, mucosal surface up, to a Sylgard-lined Perspex chamber. The right nodose ganglia, along with the rostralmost vagus and superior laryngeal nerves, were gently pulled through a small hole into an adjacent compartment of the same chamber for recording of single fibre activity. Both compartments were superfused with KBS gassed with 95% O2–5% CO2. The temperature was maintained at 35°C with a gravity driven flow rate of 6–8 ml min−1.

Extracellular recordings were performed as previously described (Riccio et al., 1996). Briefly, a fine aluminosilicate glass microelectrode pulled using a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA, U.S.A.) and filled with 3 M sodium chloride was placed into an electrode holder and connected directly to a headstage (A-M Systems, Everett, WA, U.S.A.). A return electrode of silver–silver chloride wire and a silver–silver chloride pellet ground were placed in the perfusion fluid of the recording chamber and attached to the headstage. The recorded signal was amplified (A-M Systems) and filtered (low cut-off=0.3 kHz; high cut-off=1 kHz) and the resultant activity was displayed on an oscilloscope (TDS 340, Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, U.S.A.) and a model TA240S chart recorder (Gould, Valley View, OH, U.S.A.). The data were stored on digital tape (DT-120 RA, Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for off-line analysis on a Macintosh computer using the software program The NerveOfIt (PHOCIS, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.).

Discrimination of single fibre activity, location of receptive fields and estimation of conduction velocities

Single fibre activity in the airway was discriminated by placing a concentric electrical stimulating electrode on the recurrent laryngeal nerve, through which the majority of fibres enter the trachea. The recording electrode was placed within the nodose ganglion and manipulated until single unit activity was detected. When electrically evoked action potentials were detected, the stimulator was switched off and the trachea and bronchi were gently brushed with a nylon filament. Mechanically-sensitive receptive fields were revealed when a burst of action potentials was elicited in response to filament stimulation. Conduction velocities were determined by electrically stimulating the receptive field and monitoring the time elapsed between the shock artifact and the recorded action potential. This delay was divided by the distance between the receptive field and the recording electrode to yield a conduction velocity. Only mechanically sensitive neurons were studied. These nerve fibres had little or no activity at rest, if spontaneous activity exceeded 0.1 action potential s−1, the fibre was not studied further.

Mechanical activation

Guinea-pig airway vagal afferent fibres whose cell bodies reside in nodose ganglia and whose receptive fields are located in the trachea respond in a rapidly adapting manner to punctate mechanical stimuli or increases in intraluminal tracheal pressure as described previously (McAlexander et al., 1999). Mechanical thresholds were determined with calibrated Von Frey fibres as previously described (Riccio et al., 1996). To assess the influence of epithelium removal or ion channel blockers on mechanical activation of single units a von Frey fibre was used to apply a supramaximal punctate force (≈#38;1 g) to identified receptive fields. The response recorded to this stimuli was a burst of action potentials that adapted completely in less than 2 s. In each experiment three mechanically evoked responses (delivered at ≈#38;30 s intervals) were recorded prior to (control) or following epithelium removal or application of ion channel blockers.

Electrical threshold for activation of tracheal nerve endings

Electrical stimulation of tracheal afferent nerve endings was achieved by placing a concentric stimulating electrode in juxtaposition to identified mechanically sensitive receptive fields. Stimuli delivered to the electrode were a 0.5–1 ms square pulses, delivered at various voltages, at 1 Hz. Stimuli voltage was initially supramaximal, evoking a shock artifact, each successfully followed by an action potential that was easily observed on the oscilloscope screen. Threshold stimulation voltages were determined by decreasing the voltage to the electrode until at least three consecutive shock artifacts were not followed by action potentials. Care was taken to avoid movement of the stimulating electrode throughout the experiment.

Application of ATP and ion channel blockers

For application of ATP or ion channel blockers, KBS containing the appropriate agent was superfused through only the tracheal compartment of the recording chamber. ATP and gadolinium were used at a single concentration, ATP (100 μM) was applied for 10 min and gadolinium (30 μM) was applied for 45 min. In all experiments a single receptor per preparation was studied, where the influence of multiple, increasing concentrations of amiloride and its analogues were assessed, each preparation was exposed to a single compound, at three consecutively increasing concentrations. Preparations were exposed to each concentration for 30 min.

Epithelium removal

In some experiments the epithelium was removed from the tracheal mucosal surface associated with identified mechanically-sensitive receptive fields. In each case, an audio monitor connected to the extracellular recording amplifier was used to enable the identification of mechanically sensitive fields using a dissecting microscope. The epithelium associated with and surrounding identified receptive fields was then removed by gently rubbing the mucosal surface with a moist cotton probe, as previously described (Undem et al., 1988). Successful removal of the epithelium was confirmed by visual inspection of the airway luminal surface with the aid of a dissecting microscope.

Whole cell patch-clamp recording

Nodose ganglia were dissected from adult male Hartley guinea-pigs (100–130 g) and ezymatically dissociated as previously described (Meyrelles et al., 1997). Briefly, neurons were incubated in modified Leibovitz L-15 medium (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.) containing trypsin (1 mg ml−1; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.), collagenase (1 mg ml−1; Sigma) and DNAse (0.1 mg ml−1; Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, neurons were dissociated by trituration with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Neurons were collected by centrifugation at 800 r.p.m. for 5 min, resuspended in modified L-15 containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH Biosciences, Lexena, KS, U.S.A.) and plated onto 25 mm diameter poly-D-lysine (0.1 mg ml−1; Sigma) coated coverslips. Electrophysiological recordings were made 12–36 h after plating.

Sodium currents were determined by utilizing the whole cell patch clamp technique (Hamill et al., 1981). Whole cell currents were measured with an Axopatch-1C amplifier in combination with pClamp7 software and a Digidata 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.). Currents were filtered at 10 kHz and digitally sampled at 50 kHz. Series resistance was compensated (>70%) and a P/6 protocol was utilized for leak subtraction in all traces. Patch electrodes (1–4 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (MTW150F-4, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, U.S.A.) on a Narishige pp-83 puller (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Extracellular and intracellular solutions were formulated as described by Gold et al. (1998). During electrophysiological recording, neurons were continuously perfused with an extracellular solution consisting of (mM): NaCl 35; TEA-Cl 35; choline-Cl 65; CsCl 10; MgCl2 5; HEPES 10; CaCl2 0.1 and dextrose 10. The extracellular solution was adjusted to 325 mOsm with sucrose and pH 7.4 with CsOH. The internal pipette solution consisted of (mM): NaCl 10; CsCl 100; TEA-Cl 40; MgCl2 2, HEPES 10; EGTA 11; CaCl2 1.0. The internal solution was adjusted to 310 mOsm and pH 7.2 with CsOH. All recordings were made at room temperature. Sodium currents were elicited with voltage clamp steps from −50 mV to +25 mV and from −100 mV to +40 mV. Voltage protocols were evoked prior to and 4 min after bath application of benzamil.

Drugs

Amiloride, dimethylamiloride and benzamil were obtained from Sigma. Amiloride was prepared daily in KBS at a concentration of 1 mM and further diluted with KBS as required. Stock solutions (50 mM) of dimethylamiloride and benzamil were prepared daily in 100% methanol, and diluted in KBS as required. ATP (United States Biochemical Corporation, Cleveland, OH, U.S.A.) was prepared on the day of use at a concentration of 10 mM in 0.9% saline and diluted in KBS as required. Gadolinium (III) chloride hexahydrate (Aldrich Chemical Company, Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.) was prepared daily in KBS at a concentration of 30 μM. A 1 mM stock solution of Tetrodotoxin (TTX, Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) was prepared in distilled water and stored in aliquots at −20°C, further dilutions were made in KBS.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as the arithmetic mean±s.e.mean. For extracellular recording experiments, responses of afferent neurons were expressed as the total number of action potentials recorded prior to (control) or following treatment. In some cases the number of action potentials evoked by a supramaximal mechanical stimuli following treatment was expressed in terms of the response recorded prior to treatment, i.e. as a percentage of control. Electrical threshold for activation of afferent nerve terminals was expressed in terms of a fold increase of the voltage required to evoke action potentials. Data were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student's paired t-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

General

Using extracellular electrophysiological techniques, we recorded from single afferent fibres whose cell bodies were located in nodose ganglia and whose mechanically receptive fields were identified in the trachea/bronchus. All recordings were from low-threshold mechanosensors that showed little or no spontaneous activity, conducted action potentials in the Aδ range (Table 1), and responded to sustained application of force in a rapidly adapting manner. In preliminary experiments (n=6) we determined the mechanical dynamic range of the fibres using a series of von Frey fibres. The threshold for activation was ⩽8 mg. The number of action potentials evoked by punctate mechanical stimulation delivered with von Frey fibres increased with increasing force application between 8–400 mg. A half-maximal discharge was observed at approximately 200 mg of force. To optimize the consistency of the response, we evaluated the effect of the channel blocking drugs on the response to a supramaximal force (≈#38;1 g).

Table 1.

Influence of ion channel blockers and epithelium removal on mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons

Amiloride, dimethylamiloride and benzamil

Perfusion of preparations with buffer solution containing amiloride, dimethylamiloride or benzamil caused a reduction in the number of action potentials recorded during application of a standard supramaximal punctate force to mechanically-sensitive receptive fields (Table 1). Dimethylamiloride and benzamil were similarly potent, causing inhibition of action potential discharge at a concentration of 100 μM, whereas amiloride was less potent than these compounds, causing inhibition at 1 mM (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of mechanical and electrical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons by amiloride and is analogues. (A) Typical trace from an experiment showing mechanically-evoked action potentials recorded prior to (control, upper trace) and following perfusion of the trachea with benzamil (100 μM, lower trace). Traces are from single unit recordings, the horizontal line is background noise and vertical lines represent the arrival of an action potential at the recording electrode. (B) Concentration-dependence for inhibition of mechanical activation by amiloride (n=4), dimethylamiloride (n=4) and benzamil (n=4). (C) Concentration-dependence for inhibition of electrical excitability by amiloride (n=4), dimethylamiloride (n=4) and benzamil (n=4).

Although treatment with amiloride and its analogues significantly reduced the number of action potentials evoked by a supramaximal punctate mechanical stimulis (see above), it never abolished the action potential response. Following pretreatment with the highest concentration of amiloride (1 mM, n=3) or benzamil (100 μM, n=4) tested, one or two action potentials could always be elcited even when the mechanical force was delivered at threshold levels (von Frey Fibre of 8 mg).

To evaluate the selectivity of the drugs at inhibiting mechanotransduction, we stimulated the mechanically receptive fields directly with electrical current delivered through a concentric stimulating electrode. Amiloride, dimethylamiloride or benzamil markedly reduced the sensitivity of the afferent fibres to electrical stimulation such that greater stimulation voltages were required to induce action potentials from their peripheral terminals within the trachea. The concentration-response relationship of these compounds for reducing electrical excitability (Figure 1C) was similar to that observed for inhibition of mechanical activation (Figure 1B).

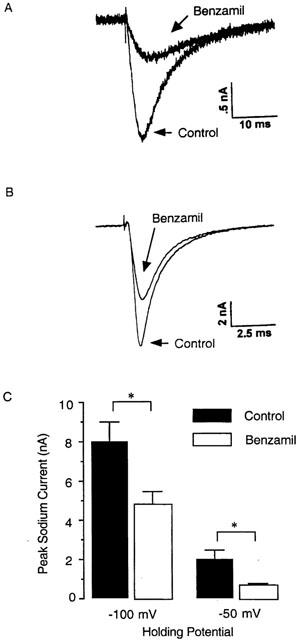

As voltage-gated sodium channels play an important role in determining the electrical excitability of neurons, we investigated the possibility that amiloride analogues caused blockade of these channels. In these experiments whole-cell patch recordings were made on acutely isolated cell bodies from guinea-pig nodose ganglia. Peak sodium currents elicited from a holding potential of −100 mV or −50 mV were significantly reduced in the presence of 100 μM benzamil (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Inhibition by benzamil of voltage-gated sodium currents in guinea-pig acutely isolated nodose ganglion neurons. (A and B) Typical traces from whole cell patch-clamp recording experiments showing sodium currents that were elicited from (A) a holding potential of −50 mV and (B) −100 mV prior to (control) and following application of benzamil (100 μM for 4 min. (C) Magnitude of peak sodium currents that were elicited from a holding potential of −50 mV and −100 mV prior to (n=3) or following (n=3) a 4 min application of 100 μM benzamil. *P<0.05.

Tetrodotoxin

Using extracellular recording we tested the possibility that the selective voltage-gated sodium channel blocker TTX would reduce mechanical activation. At concentrations of TTX>100 nM, the action potential discharge induced by mechanical or electrical stimulation was abolished (data not shown). Lower concentrations of TTX, however, mimicked the effect of amiloride and its analogues. At 30 nM, TTX reduced the number of action potentials recorded during application of a standard supramaximal punctate mechanical stimulus to nodose nerve terminals and decreased their sensitivity to electrical stimulation (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of mechanical and electrical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons by TTX. (A) Typical trace from an extracellular recording experiment showing mechanically-evoked action potentials recorded prior to (control, upper trace) and following perfusion of the trachea with TTX (30 nM, lower trace). Traces are from single unit recordings, the horizontal line is background noise and vertical lines represent the arrival of an action potential at the recording electrode. (B) Concentration-dependence for inhibition of mechanical activation by TTX (n=7). (C) Concentration-dependence for inhibition of electrical excitability by TTX (n=7 for 10 nM, n=4 for 30 nM (maximum electrical stimulation (100 volts) evoked action potentials in only four of seven preparations that were exposed to 30 nM TTX).

ATP and epithelium removal

Perfusion of the trachea/bronchus with buffer containing ATP (100 μM) failed to evoked action potential discharge (<0.1 Hz) in four of four fibres whose mechanically receptive fields were identified in the trachea/bronchus. Mechanical activation of the afferent fibres was not dependent on the epithelium. We recorded a similar number of action potentials in response to a standard supramaximal punctate mechanical stimuli before and 20 min after removal of epithelium from the mucosal surface associated with the identified mechanically-sensitive receptive fields (Table 1).

Gadolinium

The trivalent lanthanide gadolinium is a commonly used blocker of certain mechanically gated ion channels (Guilak et al., 1999; Sigurdson et al., 1992; Yang & Sachs, 1989). Perfusion of the guinea-pig trachea with buffer containing gadolinium (30 μM) for 45–60 min did not affect mechanical activation of guinea-pig airways afferent fibres (Table 1).

Discussion

This study was designed to address the hypothesis that pharmacologically blocking ENaCs leads to selective inhibition of mechanical transduction in primary vagal afferent nerve fibres innervating guinea-pig airways. Consistent with observations of baroreceptor activity (Drummond et al., 1998), amiloride and its analogues dimethylamiloride and benzamil, reduced mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent vagal neurons. However, this did not appear to occur as a result of selectively blocking mechanotransduction, but may be the result of inhibition of neuronal voltage-gated sodium currents.

ENaCs have been implicated as mechanotransducers in a variety of cell types (Awayda et al., 1995; Garcia-Anoveros & Corey, 1997; Kizer et al., 1997) including vertebrate primary afferent neurons (Drummond et al., 1998; 2000; Fricke et al., 2000; McCarter et al., 1999). However, a role for ENaCs in the mechanical activation of the peripheral terminals of primary vagal afferent neurons that innervate guinea-pig trachea is not supported by the findings of the current study. Although the number of action potential mechanical activation of these neurons was effectively decreased in the presence of the ENaC blockers amiloride (1 mM) and benzamil (100 μM) this only occurred at concentrations much greater than that reported to block ENaCs (<10 μM) (Alvarez de la Rosa et al., 2000; Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988; McNicholas & Canessa, 1997). The rank order of potency of the amiloride analogues found to reduce mechanical activation is also not consistent with a role for ENaCs in this response. Of the three analogues, benzamil is known to be the most potent at blocking ENaCs, being approximately 10 times more potent than amiloride and greater than 200 times more potent than dimethylamiloride at blocking ENaCs (Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988; McNicholas & Canessa, 1997). This rank order of potency (benzamil>amiloride>>dimethylamiloride) is incompatible with our findings regarding the rank order of potency of these three compounds for inhibition of mechanical activation (dimethylamiloride≈#38;benzamil>amiloride). In particular, our observation that dimethylamiloride is at least 10 times more potent than amiloride, is in contrast to the more than 25 fold greater potency of amiloride than dimethylamiloride for blocking ENaCs (Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988). Combined, these findings provide evidence against a role for ENaCs in mediating the reduction in mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons caused by amiloride and its analogues.

Classical studies of neuronal mechanosensors showed that following treatment with local anaesthetics such as procaine, only a single impulse could be produced by mechanical stimuli, as compared with the prolonged train of impulses that was recorded normally, suggesting that these compounds were not acting at the generator region (mechanosensor) but at the regenerative region of the nerve fibres (Paintal, 1964). Similarly, treatment with amiloride and its analogues significantly reduced the number of action potentials evoked by a supramaximal punctate mechanical stimuli, however the responses were never abolished, one or two action potentials could always be elicited, even when mechanical force was delivered at threshold levels. These findings suggest that amiloride and its analogues did not selectively inhibit mechanotransduction, but rather acted in a manner similar to local anaesthetics reducing the ability of the regenerative region of the fibres to support a prolonged train of impulses.

Amiloride and its analogues are often used as ENaC inhibitors, but are not selective in their pharmacological actions (Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988). A potentially relevant effect of these compounds is their ability to inhibit sodium conductances through channels other than ENaC. This was shown indirectly by Velly et al. (1988) where they found amiloride, dimethylamiloride and benzamil inhibited protoveratradine-induced, TTX-sensitive 22Na influx in rat synaptosomes. Interestingly, the absolute and relative concentrations of these three compounds for inhibition of TTX-sensitive 22Na influx in rat synaptosomes (dimethylamiloride≈#38;benzamil>amiloride) (Velly et al., 1988) were similar to that found in the present study for inhibition of mechanical excitability. Our observation that a relevant concentration of benzamil inhibited voltage-gated sodium currents in neurons isolated from guinea-pig nodose ganglia, provides direct evidence that these compounds are effective inhibitors of voltage-gated sodium channels.

Vagal afferent neurons, including nodose neurons are known to express TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant sodium currents (Schild & Kunze, 1997). Sodium currents elicited from a holding potential of −100 mV are due to ion conductance through both TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant channels, while currents elicited from a holding potential of −50 mV are carried predominantly by TTX-resistant channels as TTX-sensitive sodium channels are in an inactivated state at holding potential of −50 mV (Cummins & Waxman, 1997). Benzamil inhibited sodium currents elicited from a −100 mV or −50 mV holding potential. As only a relatively minor component of the current elicited from −100 mV appeared to be carried by TTX-resistant channels our data suggest that benzamil can effectively inhibit both TTX-sensitive and TTX resistant sodium channels.

There are two testable predictions of the hypothesis that amiloride analogues inhibit impulse generation in airway vagal afferent nerve fibres by blocking TTX-sensitive sodium channels. Firstly, the inhibitory effects observed with amiloride analogues should be observed when fibres are stimulated mechanically or electrically. Secondly, these inhibitory effects should be mimicked by low concentrations of TTX. Both of these predictions were satisfied in our study. Concentrations of amiloride, benzamil and dimethylamiloride that were required to inhibit mechanical activation, also reduced electrical excitability, such that higher stimulation voltages were required to evoke action potentials from peripheral afferent receptive fields in the trachea. In addition, low concentrations of TTX caused a qualitatively similar reduction in mechanical activation and decrease in electrical excitability as that seen following incubation with amiloride and it analogues. Combined, these observations suggest that inhibition of voltage-gated sodium currents by amiloride and it analogues may underlie the ability of these compounds to reduce mechanical excitably of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons.

An investigation on the mechanism by which amiloride analogues inhibit the voltage-gated sodium currents in nodose neurons is beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the guanidinium moiety of amiloride and it analogues (Kleyman & Cragoe, 1988) plays a role in their obstruction the ENaC pore (Palmer, 1990) and may also account for their apparent ability to reduce neuronal voltage-gated sodium currents. The highly selective voltage-gated sodium channel blockers TTX and saxitoxin possess a guanidinium group, which is essential for their ability to block voltage-gated sodium channels (Kao, 1966). Although it has not been directly tested, the guanidinium group of amiloride, benzamil and dimethylamiloride may play a similar role in their apparent ability to inhibit neuronal voltage-gated sodium currents.

A number of studies have reported that the trivalent lanthanide gadolinium, in the concentration range 10–20 μM, blocks mechanotransduction in a variety of cell types (Guilak et al., 1999; Sigurdson et al., 1992; Yang & Sachs, 1989). Relevant to the present work are observations that relatively low concentrations of gadolinium can inhibit mechanically-gated ion currents across somal membranes of afferent neurons isolated from both vagal and dorsal root ganglia (Cunningham et al., 1997; Kraske et al., 1998; McCarter et al., 1999). The extent to which these findings translate to mechanotransduction at the receptive endings of primary afferent nerves is unknown. Hajduczok et al. (1994) found that gadolinium inhibited pressure-evoked rabbit carotid sinus nerve activity, while Andersen & Yang (1992) found that gadolinium had no direct effect on mechanotransduction in rat aortic baroreceptors. In the present study, at a concentration of 30 μM, gadolinium had no influence on the mechanical activation of guinea-pig airways afferent neurons. The reasons for these disparate findings are unclear, but may reflect differences in the types of mechanically-gated currents expressed in cell bodies of afferent neurons and their peripheral nerve terminals.

Stretch-induced release of mediators, such as ATP from the airway epithelium (Brouns et al., 2000; Grygorczyk & Hanrahan, 1997; Homolya et al., 2000) has been hypothesized to play an indirect role in the mechanical activation of visceral afferent fibres (Burnstock, 1999). In the present study, however, we found that ATP was ineffective in activating low-threshold mechanosensor nerve terminals derived from fibres whose cell bodies reside in nodose ganglia. Removal of the epithelium did not influence mechanically-induced action potential discharge in these nerve fibres. Similarly, Fox et al. (1995) reported that guinea-pig tracheal Aδ fibre responses to hypertonic were unaffected by enzymatic removal of the epithelium. These findings are consistent with previous findings from our laboratory that demonstrated the vagal afferent innervation of the epithelium in guinea-pig trachea is derived nearly exclusively from neurons with cell bodies in the jugular ganglia, while those fibres derived from neurons with cell bodies in the nodose ganglia were not located in the epitehlium, but were found in the submucosa (Hunter & Undem, 1999). Combined, these findings indicate that neither the epithelium nor ATP is likely to be the sole determinant of mechanotransduction in low-threshold mechanosensors in guinea-pig airways.

In conclusion, mechanotransduction in nerve-endings of nodose neurons innervating guinea-pig airways occurs independently of ENaCs, gadolinium-sensitive ion channels, and epithelial cells. Amiloride, dimethylamiloride and benzamil inhibit mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent vagal neurons. This, however, does not appear to occur as a result of selectively blocking mechanotransduction, but appeared to be the result of a reduction in neuronal electrical excitability secondary to inhibition of voltage-gated sodium currents.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from The Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, U.S.A.

Abbreviations

- ENaC

epithelial sodium channel

- KBS

Krebs bicarbonate solution

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

References

- ALVAREZ DE LA ROSA D., CANESSA C.M., FYFE G.K., ZHANG P. Structure and regulation of amiloride-sensitive sodium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000;62:573–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRESEN M.C., YANG M. Gadolinium and mechanotransduction of rat aortic baroreceptors. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:H1415–H1421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AWAYDA M.S., ISMAILOV I.I., BERDIEV B.K., BENOS D.J. A cloned renal epithelial Na+ channel protein displays stretch activation in planar lipid bilayers. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;268:C1450–C1459. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.6.C1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROUNS I., ADRIAENSEN D., BURNSTOCK G., TIMMERMANS J.P. Intraepithelial vagal sensory nerve terminals in rat pulmonary neuroepithelial bodies express P2X(3) receptors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000;23:52–61. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.1.3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Release of vasoactive substances from endothelial cells by shear stress and purinergic mechanosensory transduction. J. Anat. 1999;194:335–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19430335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUMMINS T.R., WAXMAN S.G. Downregulation of tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents and upregulation of a rapidly repriming tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current in small spinal sensory neurons after nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:3503–3514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUNNINGHAM J.T., WACHTEL R.E., ABBOUD F.M. Mechanical stimulation of neurites generates an inward current in putative aortic baroreceptor neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1997;757:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRUMMOND H.A., ABBOUD F.M., WELSH M.J. Localization of beta and gamma subunits of ENaC in sensory nerve endings in the rat foot pad. Brain Res. 2000;884:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRUMMOND H.A., PRICE M.P., WELSH M.J., ABBOUD F.M. A molecular component of the arterial baroreceptor mechanotransducer. Neuron. 1998;21:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOX A.J., URBAN L., BARNES P.J., DRAY A. Effects of capsazepine against capsaicin- and proton-evoked excitation of single airway C-fibres and vagus nerve from the guinea-pig. Neuroscience. 1995;67:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00115-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRICKE B., LINTS R., STEWART G., DRUMMOND H., DODT G., DRISCOLL M., VON DURING M. Epithelial Na+ channels and stomatin are expressed in rat trigeminal mechanosensory neurons. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:327–334. doi: 10.1007/s004419900153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARCIA-ANOVEROS J., COREY D.P. The molecules of mechanosensation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1997;20:567–594. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLD M.S., LEVINE J.D., CORREA A.M. Modulation of TTX-R INa by PKC and PKA and their role in PGE2-induced sensitization of rat sensory neurons in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:10345–10355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10345.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRYGORCZYK R., HANRAHAN J.W. CFTR-independent ATP release from epithelial cells triggered by mechanical stimuli. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:C1058–C1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GSCHOSSMANN J.M., CHABAN V.V., MCROBERTS J.A., RAYBOULD H.E., YOUNG S.H., ENNES H.S., LEMBO T., MAYER E.A. Mechanical activation of dorsal root ganglion cells in vitro: comparison with capsaicin and modulation by kappa-opioids. Brain Res. 2000;856:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUILAK F., ZELL R.A., ERICKSON G.R., GRANDE D.A., RUBIN C.T., MCLEOD K.J., DONAHUE H.J. Mechanically induced calcium waves in articular chondrocytes are inhibited by gadolinium and amiloride. J. Orthop. Res. 1999;17:421–429. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAJDUCZOK G., CHAPLEAU M.W., FERLIC R.J., MAO H.Z., ABBOUD F.M. Gadolinium inhibits mechanoelectrical transduction in rabbit carotid baroreceptors. Implication of stretch-activated channels. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:2392–2396. doi: 10.1172/JCI117605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILL O.P., MARTY A., NEHER E., SAKMANN B., SIGWORTH F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOMOLYA L., STEINBERG T.H., BOUCHER R.C. Cell to cell communication in response to mechanical stress via bilateral release of ATP and UTP in polarized epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 2000;150:1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER D.D., UNDEM B.J. Identification and substance P content of vagal afferent neurons innervating the epithelium of the guinea pig trachea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;159:1943–1948. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9808078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAO C.Y. Tetrodotoxin, saxitoxin and their significance in the study of excitation phenomena. Pharmacol. Rev. 1966;18:997–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIZER N., GUO X.L., HRUSKA K. Reconstitution of stretch-activated cation channels by expression of the alpha-subunit of the epithelial sodium channel cloned from osteoblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:1013–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEYMAN T.R., CRAGOE E.J., JR Amiloride and its analogs as tools in the study of ion transport. J. Membr. Biol. 1988;105:1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01871102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOPP U.C., MATSUSHITA K., SIGMUND R.D., SMITH L.A., WATANABE S., STOKES J.B. Amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels in pelvic uroepithelium involved in renal sensory receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:R1780–R1792. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRASKE S., CUNNINGHAM J.T., HAJDUCZOK G., CHAPLEAU M.W., ABBOUD F.M., WACHTEL R.E. Mechanosensitive ion channels in putative aortic baroreceptor neurons. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H1497–H1501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCALEXANDER M.A., MYERS A.C., UNDEM B.J.Adaptation of guinea-pig vagal airway afferent neurones to mechanical stimulation J. Physiol. (London) 1999521239–247.Pt 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCARTER G.C., REICHLING D.B., LEVINE J.D. Mechanical transduction by rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;273:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00665-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCNICHOLAS C.M., CANESSA C.M. Diversity of channels generated by different combinations of epithelial sodium channel subunits. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997;109:681–692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYRELLES S.S., SHARMA R.V., WHITEIS C.A., DAVIDSON B.L., CHAPLEAU M.W. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to cultured nodose sensory neurons. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1997;51:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAINTAL A.S. Effects of drugs on vertebrate mechanoreceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1964;16:341–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALMER L.G. Epithelial Na channels: the nature of the conducting pore. Ren. Physiol. Biochem. 1990;13:51–58. doi: 10.1159/000173347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLEG A., HURT C.M. Mechanism of action of ATP on canine pulmonary vagal C fibre nerve terminals. J. Physiol. (London) 1996;490:265–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRICE M.P., LEWIN G.R., MCILWRATH S.L., CHENG C., XIE J., HEPPENSTALL P.A., STUCKY C.L., MANNSFELDT A.G., BRENNAN T.J., DRUMMOND H.A., QIAO J., BENSON C.J., TARR D.E., HRSTKA R.F., YANG B., WILLIAMSON R.A., WELSH M.J. The mammalian sodium channel BNC1 is required for normal touch sensation. Nature. 2000;407:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35039512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RICCIO M.M., KUMMER W., BIGLARI B., MYERS A.C., UNDEM B.J. Interganglionic segregation of distinct vagal afferent fibre phenotypes in guinea-pig airways. J. Physiol. (London) 1996;496:521–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHILD J.H., KUNZE D.L. Experimental and modeling study of Na+ current heterogeneity in rat nodose neurons and its impact on neuronal discharge. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3198–3209. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIGURDSON W., RUKNUDIN A., SACHS F. Calcium imaging of mechanically induced fluxes in tissue-cultured chick heart: role of stretch-activated ion channels. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:H1110–H1115. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDEM B.J., RAIBLE D.G., ADKINSON N.F., JR, ADAMS G.K., III Effect of removal of epithelium on antigen-induced smooth muscle contraction and mediator release from guinea pig isolated trachea. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;244:659–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VELLY J., GRIMA M., DECKER N., CRAGOE E.J., JR, SCHWARTZ J. Effects of amiloride and its analogues on [3H]batrachotoxinin- A 20- alpha benzoate binding, [3H]tetracaine binding and 22Na influx. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;149:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG X.C., SACHS F. Block of stretch-activated ion channels in Xenopus oocytes by gadolinium and calcium ions. Science. 1989;243:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.2466333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]