Abstract

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of chronic treatment (for 4 or 7 days) with nicotinic drugs and 20 mM KCl on numbers of surface α7 nicotinic AChR, identified by [125I]-α bungarotoxin (α-Bgt) binding, in primary hippocampal cultures and SH-SY5Y cells. Numbers of α3* nicotinic AChR were also examined in SH-SY5Y cells, using [3H]-epibatidine, which is predicted to label the total cellular population of predominantly α3β2* nicotinic AChR under the conditions used.

All the nicotinic agonists examined, the antagonists d-tubocurarine and methyllycaconitine, and KCl, upregulated [125I]-α Bgt binding sites by 20–60% in hippocampal neurones and, where examined, SH-SY5Y cells.

Upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by KCl was prevented by co-incubation with the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil or the Ca2+-calmodulin dependent kinase II (CaM-kinase II) inhibitor KN-62. Upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by nicotine or 3,[(4-dimethylamino) cinnamylidene] anabaseine maleate (DMAC) was insensitive to these agents.

[3H]-Epibatidine binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells were not affected by KCl but were upregulated in a verapamil-insensitive manner by nicotine and DMAC. KN-62 itself provoked a 2 fold increase in [3H]-epibatidine binding. The inactive analogue KN-04 had no effect, suggesting that CaM-kinase II plays a role in regulating numbers of α3* nicotinic AChR.

These data indicate that numbers of α3* and α7 nicotinic AChR are modulated differently. Nicotinic agonists and KCl upregulate α7 nicotinic AChR through distinct cellular mechanisms, the latter involving L-type Ca2+ channels and CaM-kinase II. In contrast, α3* nicotinic AChR are not upregulated by KCl. This difference may reflect the distinct physiological roles proposed for α7 nicotinic AChR.

Keywords: Nicotinic receptor, primary hippocampal cultures, SH-SY5Y cells, [125I]-α-Bgt binding, [3H]-epibatidine, nicotine, DMAC, CaM-kinase II, upregulation, KCl depolarization

Introduction

The density of high affinity [3H]-nicotine binding sites is increased in brain tissue from tobacco smokers, examined postmortem, compared with age-matched non-smoking controls (Benwell et al., 1988; Breese et al., 1997). This upregulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) is attributed to chronic exposure to nicotine present in tobacco smoke, as comparable changes in nicotinic binding site density have been observed in the brains of rodents after chronic nicotine treatment in vivo (Wonnacott, 1990; Flores et al., 1992; Rowell & Li, 1997). High affinity binding of [3H]-nicotine (and [3H]-cytisine) has been correlated with nicotinic AChR comprised of α4 and β2 subunits (Flores et al., 1992; Zoli et al., 1998). Upregulation of the α4β2 nicotinic AChR subtype has also been demonstrated in vitro, in stably transfected cell lines (Peng et al., 1994a; Bencherrif et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1995; Gopalakrishnan et al., 1997; Whiteaker et al., 1998). Both in vivo and in cell lines the upregulation of high affinity [3H]-nicotine binding sites by nicotine reflects an increase in the number of high affinity binding sites (Bmax) with no change in affinity (KD; Wonnacott, 1990; Gopalakrishnan et al., 1997) and is not accompanied by an increase in subunit mRNA, indicating that upregulation occurs through a post-transcriptional mechanism (Marks et al., 1992; Peng et al., 1994a; Bencherif et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1995).

Other subtypes of neuronal nicotinic AChR are also upregulated by chronic nicotine treatment. [125I]-α-Bungarotoxin (α-Bgt) labels a nicotinic site that is correlated with the α7 subunit in rodent brain (Séguéla et al., 1993; Barrantes et al., 1995; Orr-Urtreger et al., 1997). Chronic nicotine treatment regimes in vivo upregulate [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in some brain regions, although this response is less robust than that observed for [3H]-nicotine binding sites and requires higher nicotine concentrations that may not be relevant to human smokers (Wonnacott, 1990; Pauly et al., 1991). As with the upregulation of α4β2 nicotinic AChR, no change in α7 subunit mRNA was found (Marks et al., 1992). More recently, we reported the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in vitro: primary hippocampal cultures treated with nicotine for a few days showed a small but significant increase in the number of cell surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites (Barrantes et al., 1995), and this result has been reproduced in SH-SY5Y cells (Peng et al., 1997) and in cell lines transfected with the α7 subunit (Quik et al., 1996; Molinari et al., 1998). de koninck & Cooper (1995) observed that upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR in sympathetic neurones was evoked by chronic KCl depolarization. In contrast to nicotine-evoked upregulation, this response was accompanied by a corresponding increase in the level of α7 subunit mRNA, compared to control. KCl-evoked upregulation was proposed to result from Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels and activation of a Ca2+-calmodulin dependent kinase (CaM-kinase II) pathway (de koninck & Cooper, 1995).

In the present study we have compared the effects of chronic treatment with nicotinic ligands and KCl depolarization on [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal cultures and in the neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cell line. We have also examined the effects of the nicotinic agonist 3,[(4-dimethylamino) cinnamylidene] anabaseine maleate (DMAC), a functionally α7-selective agonist (Hunter et al., 1994; de fiebre et al., 1995). At α7 nicotinic AChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes, DMAC is a potent agonist, whilst it behaves as a weak partial agonist with little efficacy at other nicotinic AChR subtypes (de fiebre et al., 1995). In addition, the SH-SY5Y cell line, which expresses mRNA for α3, α5, α7, β2 and β4 subunits (Lukas et al., 1993; Peng et al., 1994b), has allowed comparison of the effects of drug treatments on α3* nicotinic AChR, identified by [3H]-epibatidine binding. This radioligand is membrane permeable and will label both plasma membrane bound and intracellular α3* nicotinic AChR. The concentration of [3H]-epibatidine used in this study is predicted to label predominantly α3β2* nicotinic AChR (Wang et al., 1996); only those α3-containing receptors that also incorporate the β2 subunit are reported to be upregulated by nicotine (Wang et al., 1998). We show that nicotinic agonists and KCl upregulate α7 nicotinic AChR via distinct mechanisms, whereas α3* nicotinic AChR are not responsive to KCl treatment. Preliminary accounts of some of this work have been given (Rogers & Wonnacott, 1997; Ridley & Wonnacott, 1998).

Methods

Drugs and reagents

Tissue culture media, serum and plasticware were from Gibco BRL (Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland). Media supplements, biochemicals, (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate, DMPP (1, 1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium iodide), (±)-verapamil hydrochloride, methyllycaconitine (MLA) and α-Bgt were from Sigma Co. (Poole, Dorset, U.K.). KN-62, 1-[N, O-bis-(5-isoquinolinesulphonyl)-N-methyl-L-tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine, was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation (Nottingham, U.K.); KN-04, N-[1-[N-methyl-p-(5-isoquinolinesulphonyl)-benzyl]-2-(4-phenylpiperazine)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulphonamide, was from AMS Biotechnology Ltd. (Witney, Oxon, U.K.); (±)-anatoxin-a-fumarate was purchased from Tocris Cookson (Avonmouth, U.K.). DMAC, 3,[(4-dimethylamino) cinnamylidene] anabaseine maleate, was synthesized by Organon Laboratories Ltd., Newhouse, Lanarkshire. Optiphase Safe scintillant was purchased from Fisons Chemicals (Loughborough, U.K.).

[3H]-MLA (25 Ci mmol−1) was from Tocris Cookson Ltd. (Avonmouth, U.K.). (±)-[3H]-Epibatidine (33.8 Ci mmol−1) was obtained from Dupont-NEN Ltd. (Stevenage, U.K). (−)-N-methyl-[3H]-nicotine (75 Ci mmol−1) and [125I]-Nal were obtained from Amersham International (Aylesbury, U.K.). α-Bgt was iodinated by the chloramine-T method to a specific activity of 700 Ci mmol−1 and stored in 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.5 at 4°C for up to 4 weeks.

Cell culture

Primary hippocampal cultures

High density hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared as previously described (Barrantes et al., 1995). Hippocampi from E18 foetal rats were dissociated and plated in polyethyleneimmine-coated 24×16 mm well Falcon plates at high density (1.5×105 cells per well). Initially cultures were grown in the presence of serum-supplemented (10% foetal calf serum, FCS) chemically defined Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; glucose (4.5 g l−1) : Nutrient Mixture F12 (Ham) (3 : 1), supplemented with L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 iu ml−1), streptomycin (50 μg ml−1), human transferrin (100 μg ml−1), putrescine (100 μM), insulin (5 μg ml−1), progesterone (20 nM), sodium selenite (30 nM)) for 2 h, to ensure attachment of neuronal cells. After 2 h the medium was replaced with serum-free chemically defined medium and the neurones were allowed to mature for 3 days (Barrantes et al., 1995). Cultures were fed every 4 days by replacing half of the medium in the wells with fresh chemically defined medium. Drug dilutions were applied to mature cultures for either 4 or 7 days.

SH-SY5Y cells

Stock cultures of SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were routinely maintained in a DMEM:Ham's F12 (1 : 1) modified medium containing 1% non-essential amino-acids (NEAAs) and supplemented with FCS (15%), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 iu ml−1) and streptomycin (50 μg ml−1). Cultures were seeded into 75 cm2 flasks containing 20 ml of supplemented medium and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2/humidified air. Stock cultures were passaged 1 : 4 weekly and fed twice weekly. For binding assays, SH-SY5Y cells were subcultured in 24 well plates at a seeding density of 2×105 cells per well adapted from Vaughan et al. (1993). Once confluent, cultures were treated with drugs for 4 days before assaying.

Drug treatment

Initial experiments were performed on hippocampal neurones chronically treated with a number of drugs, alone or in combination, for 7 days. Subsequently a 4 day drug exposure was employed for both the primary hippocampal and SH-SY5Y cultures. Nicotine, KCl and verapamil were made up freshly in either ‘conditioned' chemically defined medium for hippocampal cultures or in DMEM:Ham's F12 supplemented medium for SH-SY5Y cells on day 1 of drug treatment. KN-62, KN-04 and DMAC were made up in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) in stock solutions of 10 mM; the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%. Chronic exposure to this concentration of DMSO had no effect on subsequent ligand binding assays. After 4 or 7 days of drug treatment, cultures were assayed for binding of either [125I]-α-Bgt (hippocampal and SH-SY5Y cultures) or [3H]-epibatidine (SH-SY5Y cultures).

Radioligand binding assays

[125I]-α-Bgt binding to hippocampal and SH-SY5Y cultures

Surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites on hippocampal cultures grown in the presence or absence of drugs for either 4 or 7 days in 24×16 mm culture wells were measured essentially as described by Barrantes et al. (1995). In brief, on the day of assay, cultures were washed for 3×10 min with warm medium, then incubated for 3 h at 37°C before a final wash with warm medium to remove all traces of drugs from the cultures. Fresh chemically defined medium containing 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (200 μl) was added and non-specific binding was defined by pre-incubation of culture wells (in triplicate) with 2 μM α-Bgt for 60 min at 25°C. Total binding was determined in parallel cultures pre-incubated without α-Bgt. Then [125I]-α-Bgt (final concentration 10 nM) was added to all culture wells and the incubation continued for a further 2 h at 25°C. The cultures were subsequently washed three times with 1 ml warm phosphate buffered saline (mM): PBS; 150 NaCl, 8 K2HPO4, 2 KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 37°C. They were then solubilized in 0.1 M NaOH (200 μl; 16 h at 4°C), counted for radioactivity (Packard Cobra II Auto Ultra γ counter) and assayed for protein (Markwell et al., 1978). Radioactivity bound per well was directly related to the protein content of the same well.

[3H]-Epibatidine binding to SH-SY5Y cultures

The cellular population of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites was monitored in SH-SY5Y cells in situ, in 24-well plates, based on the protocol of Whiteaker et al. (1998). Cultures were washed as above and incubated with 1 ml SH-SY5Y medium containing [3H]-epibatidine (500 pM) for 2 h at 25°C. Non-specific binding was defined in parallel cultures in the presence of 1 mM nicotine. The cultures were subsequently washed as above and solubilized in 800 μl 0.1 M NaOH (16 h at 4°C). An aliquot (500 μl) was added to 5 ml Optiphase Safe scintillant (Fisons Chemicals, Loughborough, U.K.) and counted for radioactivity in a Packard Tri-Carb liquid scintillation counter 1600 spectrometer (counting efficiency 45%) and a 200 μl aliquot was assayed for protein (Markwell et al., 1978).

Competition binding assays with DMAC

DMAC was assessed in competition binding assays, using [125I]-α-Bgt, [3H]-MLA, [3H]-epibatidine and [3H]-nicotine binding to rat brain P2 membranes, as described by Davies et al. (1999). In brief, for [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, rat brain P2 membranes were diluted in assay buffer (phosphate buffer supplemented with 0.1% (w v−1) BSA) and incubated with [125I]-α-Bgt (final concentration 1 nM) and a range of dilutions of the competing drug, DMAC or unlabelled α-Bgt, for 3 h at 37°C. Then, samples were diluted with 0.5 ml ice cold phosphate buffered saline (mM): (PBS Na2HPO4 20, KH2PO4 5, NaCl 150, pH 7.4), centrifuged at 12,000×g (2 min), resuspended in 1.25 ml of ice cold PBS and re-centrifuged (12,000×g for 2 min). The supernatant fraction was removed and the radioactivity contained in the pellets was determined using a Packard Cobra II gamma-counter to detect bound [125I]-α-Bgt.

Competition binding assays with [3H]-MLA, [3H]-epibatidine and [3H]-nicotine were as follows: rat brain P2 membranes were diluted in assay buffer (Krebs Ringer-Tris N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N[2-ethane-sulphonic acid] (HEPES) buffer composed of (mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.8, CaCl2 2.5, HEPES 20, Tris 200, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride 0.1, 0.01% sodium azide, pH 7.4) to give the desired protein content (typically 1.0 mg ml−1 protein). In [3H]-MLA competition binding assays, samples were supplemented with 0.1% (w v−1) BSA to reduce non-specific binding. Samples (250 μl) were incubated with either [3H]-MLA, [3H]-epibatidine or [3H]-nicotine (final concentration 1 nM, 200 pM and 10 nM respectively) and a range of dilutions of the competing drug, DMAC, for 2 h at 37°C for [3H]-MLA, and 2.5 h at 20°C or 30 min at 20°C, followed by 1 h at 4°C, for [3H]-epibatidine and [3H]-nicotine respectively. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of unlabelled MLA (1 μM) or nicotine (1 mM). After incubation, samples were diluted with 4 ml of ice cold PBS at 4°C and rapidly filtered through Whatman GFA/E glass filters (Gelman Sciences), pre-soaked in 0.3% polyethyleneimmine for 3 h to reduce non-specific binding, using a Brandel Cell Harvester. Filters were washed twice with 4 ml of ice cold PBS at 4°C. Bound radioactivity was determined in a Packard Tri-Carb 1600 scintillation spectrometer (counting efficiency 45%).

Determination of IC50 and Ki

IC50 values were calculated by fitting data points from competition assays to the Hill equation, using the non-linear least squares curve fitting facility of Sigma Plot version 2.0 for Windows:

where nH is the Hill number, [Ligand] is the concentration of the competing ligand, and IC50 is the concentration of competing ligand that displaces 50% of specific radioligand binding. The affinity constant (Ki) values were derived from IC50 values according to the method of Cheng & Prusoff (1973):

where [Ligand] is the concentration of radioligand and KD is the equilibrium displacement binding constant. KD values of 1 nM for [125I]-α-Bgt and [3H]-MLA, 10.2 pM for [3H]-epibatidine and 10 nM for [3H]-nicotine were assumed (Whiteaker et al., 1998; Davies et al., 1999; Sharples et al., 2000).

Results

Upregulation of [125I]-α Bgt binding sites in hippocampal cultures

Pharmacological characterization: effects of nicotinic agonists, antagonists and KCl

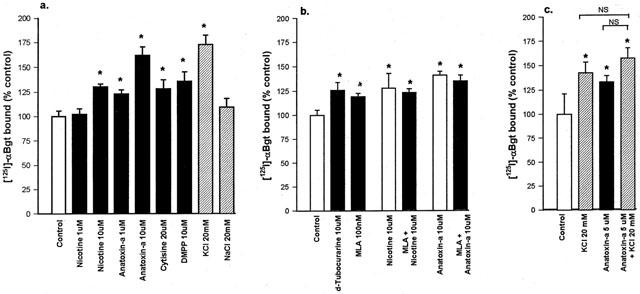

Hippocampal cultures were grown in the presence of various nicotinic drugs for 7 days, and surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites were assayed in situ. Chronic exposure to agonists increased the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by between 20 and 60% above control (Figure 1a). The upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in response to exposure to (−)nicotine was concentration-dependent: whereas 1 μM nicotine had no influence on binding site density, 10 μM nicotine produced an increase of 30±3% (n=27). Higher concentrations of nicotine (100 μM) were toxic to the cells within 7 days. (±)-Anatoxin-a also provoked a concentration-dependent effect, with 1 μM and 10 μM anatoxin-a upregulating [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by 23±4% (n=5) and 56±6% (n=16) respectively. Cytisine (20 μM) and DMPP (10 μM) also produced significant increases in binding site density (Figure 1a). The values obtained for upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites represent a real increase in numbers of surface α7 nicotinic AChR, rather than reflecting a change in cell density, as binding site density was calculated in terms of protein, determined in parallel for each culture well assayed (see Methods).

Figure 1.

The effect of chronic drug treatment on numbers of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal cultures. Hippocampal cultures from E18 rat foetuses were treated for 7 days with (a) nicotinic agonists or salts, (b) nicotinic antagonists in the presence or absence of agonist, or (c) KCl and agonist separately and in combination. Following extensive washing, as described in Methods, binding assays for surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites were carried out on cells in situ. Specific [125I]-α-Bgt binding to control cells, cultured in parallel in the absence of drug, was taken to be 100%. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of at least four independent cultures, each culture was treated and assayed in triplicate for each drug condition. *Significantly different from control, P<0.05, (one way ANOVA). NS, not significantly different.

Hippocampal cultures were also treated for 7 days with nicotinic antagonists, with or without agonist present. Methyllycaconitine (MLA; 100 nM) and d-tubocurarine (10 μM) also upregulated the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, by 20 and 26% respectively (Figure 1b). The upregulation produced by 100 nM MLA appeared to be maximal, as no further increase was seen following 7 days' exposure to 10 μM MLA (data not shown). To investigate whether agonist and antagonist effects were additive, cultures were exposed to 10 μM nicotine plus 100 nM MLA for 7 days. The 23% increase in [125I]-α-Bgt binding (Figure 1b) was not significantly different from that seen with MLA alone. Similarly, there was a lack of additivity when cultures were exposed to 10 μM anatoxin-a plus 100 nM MLA (Figure 1b).

To determine if general depolarization has any influence on the numbers of surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, cultures were exposed for 7 days to medium in which the KCl concentration was increased from 5 to 20 mM. This produced a 72±10% (n=18) increase in the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, whereas a corresponding increase in NaCl to produce the same change in osmolarity had no significant effect (Figure 1a). Higher concentrations of KCl (>30 mM) were toxic to the primary cultures. Concomitant treatment with anatoxin-a and KCl did not increase the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites above that achieved with either agent alone (Figure 1c, n=4).

The drug exposure time for hippocampal cultures was shortened to 4 days with nicotine or KCl (Table 1). In control cultures there was no increase in the density of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites between 4 and 7 days. Nicotine and KCl produced similar increases in numbers of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites after 4 days, compared to those seen after 7 days. Therefore subsequent experiments used a 4 day drug exposure protocol.

Table 1.

Upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt and [3H]-epibatidine binding sites in rat hippocampal or SH-SY5Y cultures treated with either nicotine (10 μM), DMAC (10 μM) or KCl (20 mM) for 4 or 7 days

We also examined the effects of DMAC, a novel agonist with putative α7-selectivity (de fiebre et al., 1995). The ability of DMAC to displace the binding of [125I]-α-Bgt, [3H]-MLA, [3H]-nicotine and [3H]-epibatidine from rat brain membranes was assessed in competition binding assays (Table 2). DMAC was 4–5 times more potent at displacing [3H]-epibatidine and [3H]-nicotine binding than at displacing the α7-selective radioligands [125I]-α-Bgt and [3H]-MLA. When applied to hippocampal cultures for 4 days, DMAC elicited a concentration dependent upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites: 1 μM DMAC had no effect whereas 10 μM DMAC increased [125I]-α-Bgt binding by 26±1% above control levels (n=3, significantly different from control, P<0.05, one way ANOVA). This is similar to the degree of upregulation produced by 10 μM nicotine after either 4 or 7 days of treatment (Table 1).

Table 2.

Potency of DMAC in competition assays for nicotinic radioligand binding to rat brain membranes

Mechanisms of nicotinic agonist- and KCl-evoked upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal cultures

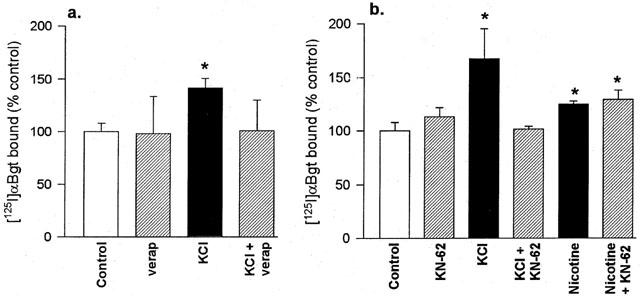

To investigate whether the upregulation induced by nicotine (10 μM) and KCl (20 mM) might arise through a common pathway, further experiments were performed in the presence of inhibitors of putative intermediate steps. The effect of verapamil, an L-type Ca2+ channel blocker, was examined to determine if depolarization-induced Ca2+ entry might play a role in the upregulation of hippocampal [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites. Exposure of hippocampal cultures to 5 μM verapamil alone for 4 days had no significant effect on numbers of binding sites, but verapamil prevented the upregulation elicited by chronic treatment with KCl (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

The effects of verapamil and KN-62 on the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal cultures. Cultures were treated for 4 days with 20 mM KCl or 10 μM nicotine, in the presence or absence of (a) 5 μM verapamil or (b) 5 μM KN-62. Controls with no drug treatment were cultured in parallel. Specific [125I]-α-Bgt binding to cells in situ was determined as described in Methods, and binding to control cultures was taken to be 100%. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of at least four independent cultures, each culture was treated and assayed in triplicate for each drug condition. *Significantly different from control, P<0.05, (one way ANOVA).

To determine whether upregulation involves a CaM-kinase II pathway, cultures were incubated with either 10 μM nicotine or 20 mM KCl in the absence or presence of KN-62 (Figure 2b), a selective CaM-kinase II inhibitor (Tokumisto et al., 1990). KN-62 itself had no significant effect on the level of [125I]-α-Bgt binding to these cultures (113.1±8.8% of control). KCl upregulated [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by 67.1±27.9% above control, and this was totally abolished by co-incubation with KN-62 (101.7±2.6% of control). In contrast, nicotine-induced upregulation was not blocked at all in the presence of 5 μM KN-62; the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites was 29±9% above control after treatment with nicotine plus KN-62, compared with a 25±3% increase produced by nicotine alone (Figure 2b). These results suggest that nicotine and KCl evoke upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal neurones through different cellular mechanisms. Studies on primary hippocampal cultures are severely limited by the paucity of material available, and inherent variability between different cultures. To circumvent these limitations, the SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell line was chosen for further studies.

Upregulation of nicotinic AChR binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells

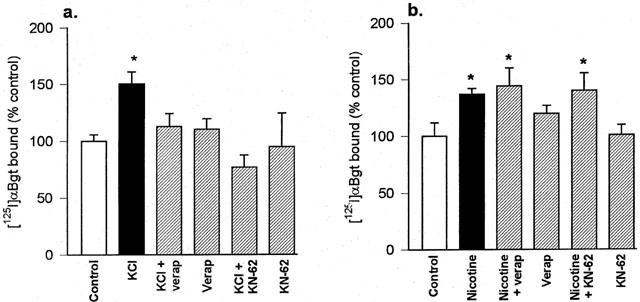

Upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells

In the absence of drugs, SH-SY5Y cells expressed 25 fmol of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites mg protein−1 (Table 1). Nicotine (10 μM), DMAC (10 μM) and KCl (20 mM), applied for 4 days, increased the number of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by 37, 20, and 51% respectively (Table 1). These values closely parallel the magnitude of changes in [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites observed in hippocampal cultures (Table 1).

The effects of verapamil and KN-62 on KCl-evoked upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells accord with those seen in primary hippocampal cultures: the upregulation produced by KCl was blocked in the presence of these drugs (Figure 3a). However, neither verapamil nor KN-62 affected the increase in [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in response to chronic nicotine treatment (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

The upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells treated with (a) KCl or (b) nicotine, and the effects of verapamil and KN-62. SH-SY5Y cells were cultured for 4 days with 20 mM KCl, 10 μM nicotine or no addition (control), in the presence or absence of 5 μM verapamil or 5 μM KN-62. Specific [125I]-α-Bgt binding to cells in situ was determined as described in Methods, and binding to control cultures was taken to be 100%. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of at least four independent cultures, each culture was treated and assayed in triplicate for each drug condition. *Significantly different from control, P<0.05, (one way ANOVA).

Upregulation of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells

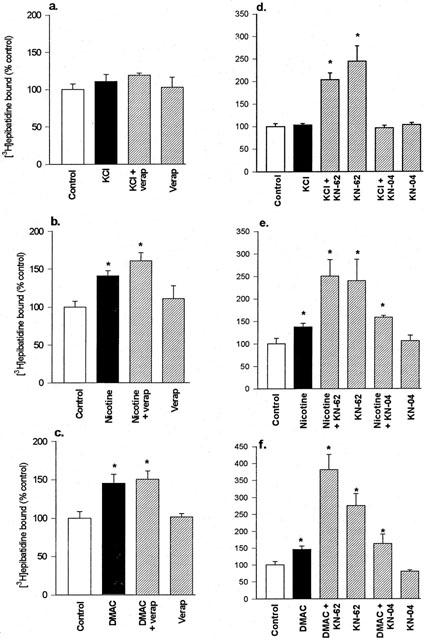

In addition to [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, SH-SY5Y cells also express α3* nicotinic AChR that can be labelled by [3H]-epibatidine (Peng et al., 1997). Cultures were assayed in situ with 500 pM [3H]-epibatidine: this concentration of radioligand is predicted to predominantly measure α3β2* nicotinic AChR (Wang et al., 1996). In the absence of drugs, SH-SY5Y cultures expressed 69 fmoles [3H]-epibatidine binding sites mg protein−1 (Table 1). Chronic nicotine (10 μM) treatment of SH-SY5Y cultures for 4 days upregulated [3H]-epibatidine binding sites by 36%. DMAC (10 μM) produced a comparable upregulation of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites of 43% (Table 1; Figure 4). These responses are similar in magnitude to the changes provoked in surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites. In contrast, KCl depolarization (20 mM for 4 days) failed to increase the number of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites (Table 1 and Figure 4a,d).

Figure 4.

The upregulation of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites in SH-SY5Y cells treated with (a, d) KCl, (b, e) nicotine and (c, f) DMAC, and the effects of verapamil, KN-62 and KN-04. SH-SY5Y cells were cultured for 4 days with 20 mM KCl, 10 μM nicotine, 10 μM DMAC or no addition (control), in the presence or absence of (a, b, c) 5 μM verapamil or (d, e, f) 5 μM KN-62 or 5 μM KN-04. Specific [3H]-epibatidine binding to cells in situ was determined as described in Methods, and binding to control cultures was taken to be 100%. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean of at least four independent cultures, each culture was treated and assayed in triplicate for each drug condition. *Significantly different from control, P<0.05, (one way ANOVA).

Verapamil, applied to SH-SY5Y cultures for 4 days in the presence of agonist or KCl, failed to prevent the agonist-induced upregulation of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites (Figure 4a,b,c). Verapamil alone had no effect on the numbers of binding sites. In contrast, KN-62 applied to SH-SY5Y cultures for 4 days in the absence of agonist or KCl produced a marked upregulation of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites, to approximately 150% above control (Figure 4d,e,f). To determine if this was a specific effect, the inactive analogue of KN-62, KN-04, was examined. KN-04 alone had no effect on the number of [3H]-epibatidine binding sites, when compared to the control condition, and KN-04 did not diminish agonist-evoked upregulation (Figure 4d,e,f). This suggests that KN-62 elicits the up-regulation of α3* nicotinic AChR through inhibition of CaM-kinase II.

Discussion

In agreement with previous reports, this study has demonstrated that chronic exposure to nicotinic agonists, antagonists and KCl upregulates the numbers of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in primary cultures of hippocampal neurones and in SH-SY5Y cells. However, the key novel finding of the present study is that the underlying mechanisms differ between agonist- and KCl-induced upregulation: only the latter is blocked by the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil and the CaM-kinase II inhibitor KN-62. α3* Nicotinic AChR in SH-SY5Y cells, characterized by [3H]-epibatidine binding, differ from α7 nicotinic AChR, labelled by [125I]-α-Bgt, in their insensitivity to KCl treatment, although KN-62 itself was found to upregulate [3H]-epibatidine binding sites.

Upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR

All the nicotinic agonists examined upregulated [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal neurones (Figure 1) or SH-SY5Y cells (Table 1) after 4 or 7 days of drug treatment. Previously, nicotine has been shown to upregulate [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites without a change in KD or subunit mRNA levels (Quik et al., 1996; Peng et al., 1997; Molinari et al., 1998). As the present binding assays with this large polypeptide toxin were carried out on cells in situ, only the surface population of receptors was labelled. Moreover, the fact that α-Bgt binds with high affinity to all states of the receptor makes the equation of the increased density of binding sites with increased receptor number unequivocal. However, the possibility of internalization of α-Bgt-receptor complexes during the assay has not been ruled out (Ke et al., 1998). The level of upregulation provoked by nicotine (about 30%) is consistent with previous reports for endogenously expressed α7 nicotinic AChR (Barrantes et al., 1995; Peng et al., 1997), and is similar to the magnitude of increases reported after in vivo administration of nicotine (Pauly et al., 1991). Upregulation produced by nicotine and anatoxin-a was concentration dependent, with 1 μM anatoxin-a evoking increases in numbers of binding sites comparable to the changes produced by 10 μM nicotine. This is consistent with the 10 fold greater potency of anatoxin-a, compared with nicotine, for α7 nicotinic AChR (Macallan et al., 1988; Alkondon & Albuquerque, 1993). DMPP (10 μM) also upregulated [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal neurones, to a similar extent as 10 μM nicotine. As the quaternary nitrogen of DMPP should render it cell impermeable, this result argues that the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding to hippocampal neurones is triggered by agonist acting at the cell surface. A similar conclusion for the upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR in SH-SY5Y cells was reached using carbamoylcholine (Peng et al., 1997).

The anabaseine derivative DMAC was comparable to nicotine in its concentration dependence for upregulating [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites. DMAC is a putative α7-selective agonist, reported to have higher affinity for [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites than for [3H]-nicotine binding sites in brain membranes (de fiebre et al., 1995). In our hands, DMAC (synthesized as the maleate salt) was 10 fold less potent at α7 binding sites than previously reported (Table 2). Nevertheless, there was only a 4 fold difference in potency of DMAC between α7 sites and high affinity agonist binding sites (predominantly α4β2 subtype) in rat brain membranes. Nicotine, in contrast, is more than 200 times less potent at [125I]-α-Bgt sites than at [3H]-nicotine sites (de fiebre et al., 1995; Macallan et al., 1988). Therefore we might have expected chronic treatment with 1 μM DMAC to upregulate [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites, as well as the higher concentration of drug tested. Indeed, the related compound 3-(2, 4)-dimethoxybenzylidene anabaseine (GTS-21) upregulated heterologously expressed α7 binding sites to a similar extent as nicotine but with greater potency (Molinari et al., 1998).

The ability of nicotinic AChR antagonists to either elicit or prevent upregulation is less consistent between studies, and between receptor subtypes. We previously found antagonists to have little, if any, ability to upregulate α4β2 nicotinic AChR in the M10 transfected cell line, and only d-tubocurarine showed any tendency to inhibit agonist-induced upregulation of α4β2 binding sites (Whiteaker et al., 1998). In SH-SY5Y cells, Peng et al. (1997) reported that millimolar concentrations of d-tubocurarine, dihydro-β-erythroidine and mecamylamine did not upregulate either α3 or α7 subtypes, and did not prevent the nicotine-induced upregulation of α3, but partially blocked the upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR in response to 0.5 mM nicotine. These observations led to the tentative suggestion that upregulation of α3 and α7 nicotinic AChR may proceed by different mechanisms, the latter requiring receptor activation by agonists (Peng et al., 1997). This view is not supported by the present findings, where d-tubocurarine and MLA both upregulated [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in hippocampal neurones. Antagonist-induced upregulation was not additive with that produced by agonists (Figure 1b). Upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by the antagonists d-tubocurarine and mecamylamine (but not by hexamethonium or dihydro-β-erythroidine) was first reported for adrenal medullary chromaffin cells (Quik et al., 1987). Molinari et al. (1998) described the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by high concentrations of MLA in HEK 293 cells stably expressing α7 nicotinic AChR. Taken together, the consensus from these studies is that at least certain antagonists, notably d-tubocurarine and MLA, can induce the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites. This suggests that binding to (or near) the agonist binding site, rather than activation of the receptor, is sufficient to trigger upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR, perhaps by stabilizing a particular conformation of the receptor.

Exposure to 20 mM KCl for 4 or 7 days increased the surface binding of [125I]-α-Bgt to hippocampal neurones and SH-SY5Y cells. This is in agreement with previous reports for sympathetic neurones (de koninck & Cooper, 1995) and for GH4C1 cells transfected with human α7 (Quik et al., 1996). The latter study confirmed that the increase in [125I]-α-Bgt binding after treatment of cells for 3 days with 50 mM KCl was due to an increase in binding site density, rather than a change in affinity. In the present study, the KCl-evoked upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites was sensitive to both the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil and the CaM-kinase II inhibitor KN-62 (Figures 2 and 3) consistent with findings for sympathetic neurones (de koninck & Cooper, 1995). The key observation that verapamil and KN-62 did not prevent nicotine-induced upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt sites indicates that KCl and nicotine upregulate α7 nicotinic AChR by different mechanisms.

There is a well established role for sustained Ca2+ entry via L-type Ca2+ channels and activation of CaM-kinase II in gene activation, via phosphorylation of transcription factors and regulation of immediate early genes (Greenberg et al., 1992; Ghosh & Greenberg, 1995). Indeed de koninck & Cooper (1995) found that an increase in α7 gene expression paralleled the increase in surface [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites in sympathetic neurones treated with KCl. Thus it is plausible that KCl upregulates [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites through activation of L-type Ca2+ channels and the subsequent activation of CaM-kinase II, leading to an increase in α7 subunit gene transcription. In contrast, Peng et al. (1994b) found no change in α7 mRNA in SH-SY5Y cells after treatment with 1 mM nicotine for 4 days. Therefore nicotine appears to upregulate [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites through a post-transcriptional mechanism, independent of voltage-operated Ca2+ channels and CaM-kinase II. However, KCl- and nicotinic agonist-evoked increases in [125I]-α-Bgt sites were not additive in hippocampal neurones, suggesting that some common downstream event may limit surface expression.

Upregulation of α3* nicotinic AChR

SH-SY5Y cells enabled us to compare the upregulation of α3* nicotinic AChR, identified by [3H]-epibatidine binding. α3* Nicotinic AChR are heterogeneous in these cells, potentially comprising: α3β2, α3β4, α3α5β2, α3α5β4 and α3α5β2β4 subunit combinations. Based on immunodepletion experiments, 56% of α3* nicotinic AChR were found to also include the β2 subunit (Wang et al., 1996), and only those α3* receptors that incorporate the β2 subunit were upregulated by nicotine (Wang et al., 1998). β2* and β4* receptors can be distinguished by their affinities for [3H]-epibatidine: β4 confers a lower affinity (KD 7 nM), whereas β2-containing α3* receptors equate with a higher affinity (KD 150 pM) component of [3H]-epibatidine binding to SH-SY5Y cells (Wang et al., 1996). By using a modest concentration of this radioligand (500 pM) in our binding assays, we have presumably measured predominantly β2* nicotinic AChR.

Nicotine (10 μM 4 days) consistently produced a 40% increase in [3H]-epibatidine binding to intact cells (Figure 4); this is lower than the 3 fold increase reported by Wang et al. (1998) but may be a reflection on the lower concentrations of nicotine used in this study compared to the concentration (1 mM) used by Wang et al. (1998). DMAC (10 μM) and nicotine (10 μM) upregulated [3H]-epibatidine binding sites to a similar extent. The α7-selectivity ascribed to DMAC comes from its full agonism at α7 nicotinic AChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes, whereas it behaves as a weak partial agonist with little efficacy at other nicotinic AChR subtypes (de fiebre et al., 1995). Grottick et al. (2000) recently reported that DMAC failed to mimic behavioural effects of nicotine ascribed to β2* nicotinic AChR, consistent with DMAC being functionally selective for α7 nicotinic AChR. However, chronic treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with DMAC yielded changes in α3* binding site density that are comparable to those produced by nicotine. Thus DMAC is capable of upregulating both [125I]-α-Bgt sites and [3H]-epibatidine sites (Table 1 and Figure 4). If DMAC has very low functional efficacy at α3* nicotinic AChR in SH-SY5Y cells, as observed in Xenopus oocytes (de fiebre et al., 1995), binding to the agonist binding site, rather than activation of the receptor, must be sufficient to elicit upregulation. This is the case for other partial agonists, with respect to α4β2 nicotinic AChR (Whiteaker et al., 1998; Sharples et al., 2000), and has implications for the therapeutic application of such drugs.

As with the nicotine-evoked upregulation of α7 nicotinic AChR, the increase in [3H]-epibatidine binding sites after chronic treatment with nicotine or DMAC was unaffected by verapamil (Figure 4). The sensitivity to CaM-kinase II inhibition of agonist-evoked upregulation of α3 nicotinic AChR could not be ascertained because of the ability of KN-62 to provoke a 2 fold increase in [3H]-epibatidine binding itself. This appears to result from the specific inhibition of CaM-kinase II, as the inactive structural analogue KN-04 was without effect. Hence CaM-kinase II may normally exert an inhibitory influence on numbers of α3* nicotinic AChR.

α3* Nicotinic AChR in SH-SY5Y cells were unresponsive to chronic KCl treatment. As SH-SY5Y cells faithfully reproduce the upregulation of [125I]-α-Bgt binding sites by KCl characterized in hippocampal neurones (c.f. Table 1), sympathetic neurones (de koninck & Cooper, 1995) and heterologously expressed α7 nicotinic AChR (Quik et al., 1996), this suggests that α3* and α7 nicotinic AChR are differentially regulated by depolarization. This is reinforced by the lack of effect of KCl on any nicotinic AChR subunit mRNA, other than α7, in sympathetic neurones (de koninck & Cooper, 1995). The ability of chronic depolarization to uniquely influence α7 expression may reflect the particular physiological roles of α7 nicotinic AChR in neurones, for example in nervous system development, neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity (Role & Berg, 1996; Mansvelder & McGehee, 2000).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a MRC Collaborative Studentship (to D. Ridley) in conjunction with Organon Laboratories, Newhouse, Scotland, and a grant from BAT Co. (to S. Wonnacott). We are grateful to Organon Laboratories for the provision of DMAC.

Abbreviations

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- α-Bgt

α-bungarotoxin

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CaM-kinase II

Ca2+-calmodulin dependent kinase II

- DMAC

3,[(4-dimethylamino) cinnamylidene] anabaseine maleate

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

- DMPP

1, 1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium iodide

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- GTS-21

3-(2, 4)-dimethoxybenzylidene anabaseine

- HEPES

N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′[2-ethane-sulphonic acid]

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- KN-62

(1-[N, O-bis-(5-isoquinolinesulphonyl)-N-methyl-L-tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine

- KN-04

N-[1-[N-methyl-p-(5-isoquinolinesulphonyl)-benzyl]-2-(4-phenylpiperazine)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulphonamide

- MLA

methyllycaconitine

- NEAAs

non-essential amino-acids

References

- ALKONDON M., ALBUQUERQUE E.X. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;265:1455–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRANTES G.E., ROGERS A.T., LINDSTROM J., WONNACOTT S. α-Bungarotoxin binding sites in rat hippocampal and cortical cultures: initial characterisation, colocalisation with α7 subunits and up-regulation by chronic nicotine treatment. Brain Res. 1995;672:228–236. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01386-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENCHERIF M., FOWLER K., LUKAS R.J., LIPPIELLO P.M. Mechanisms of up-regulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in clonal cell lines and primary cultures of fetal rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;275:987–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENWELL M.E.M., BALFOUR D.J.K., ANDERSON J.M. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (−)-[3H]-nicotine binding sites in human brain. J. Neurochem. 1988;50:1243–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREESE C.R., MARKS M.J., LOGEL J., ADAMS C.E., SULLIVAN B., COLLINS A.C., LEONARD S. Effect of smoking history on [3H]-nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;282:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y.-C., PRUSOFF W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (IC50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharm. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES A.R.L., HARDICK D.J., BLAGBROUGH I.S., POTTER B.V.L., WOLSTENHOLME A.J., WONNACOTT S. Characterisation of the binding of [3H]methylycaconitine: a new radioligand for labelling α7-type neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacol. 1999;38:679–690. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE FIEBRE C.M., MEYER E.M., HENRY J.C., MURASKIN S.I., KEM W.R., PAPKE R.L. Characterisation of a series of anabaseine-derived compounds reveals that the 3-(4)-dimethylaminocinnamylidine derivative is a selective agonist at neuronal α7/125I-α-bungarotoxin receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharm. 1995;47:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE KONINCK P., COOPER E. Differential regulation of neuronal nicotinic ACh receptor subunit genes in cultured neonatal rat sympathetic neurones: specific induction of α7 by membrane depolarisation through a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase pathway. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:7966–7978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07966.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLORES C.M., ROGERS S.W., PABREZA L.A., WOLFE B.B., KELLAR K.J. A subtype of nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is composed of α4 and β2 subunits and is upregulated by chronic nicotine treatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH A., GREENBERG M.E. Calcium signalling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science. 1995;268:239–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7716515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOPALAKRISHNAN M., MOLINARI E.J., SULLIVAN J.P. Regulation of human α4β2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by cholinergic channel ligands and second messenger pathways. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:524–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENBERG M.E., THOMPSON M.A., SHENG M. Calcium regulation of immediate early gene transcription. J. Physiol. (Paris) 1992;86:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(05)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROTTICK A.J., TRUBE G., CORRIGAL W.A., HUWYLER J., MALHERBE P., WYLER R., HIGGINS G.A. Evidence that nicotinic α7 receptors are not involved in the hyperlocomotor and rewarding effects of nicotine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;294:1112–1119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUNTER B.E., DE FIEBRE C.M., PAPKE R.L., KEM W.R., MEYER E.M. A novel nicotinic agonist facilitates induction of long term potentiation in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Letts. 1994;168:130–134. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KE L., EISENHOUR C.M., BENCHERIF M., LUKAS R.J. Effects of chronic nicotine treatment on expression of diverse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. I. Dose- and time-dependent effects of nicotine treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;286:825–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUKAS R.J., NORMAN S.A., LUCERO L. Characterisation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by cells of the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma clonal line. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1993;4:1–12. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACALLAN D.R.E., LUNT G.G., WONNACOTT S., SWANSON K.L., RAPOPORT H., ALBUQUERQUE E.X. Methyllycaconitine and (+)-anatoxin-a differentiate between nicotinic receptors in vertebrate and invertebrate nervous systems. FEBS Lett. 1988;226:357–363. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANSVELDER N., MCGEHEE D. Long term potentiation of excitatory inputs to brain reward areas by nicotine. Neuron. 2000;27:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKS M.J., PAULY J.R., GROSS S.D., DENERIS E.S., HEINEMANN S.F., COLLINS A.C. Nicotine binding and nicotinic receptor subunit RNA after chronic nicotine treatment. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:2765–2784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02765.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARKWELL M.A.K., HAAS S.M., BIEBER L.L., TOLBERT N.E. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal. Biochem. 1978;87:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOLINARI E.J., DELBONO O., MESSI M.L., RENGANATHAN M., ARNERIC S.P., SULLIVAN J.P., GOPALAKRISNAN M. Up-regulation of human α7 nicotinic receptors by chronic treatment with activator and antagonist ligands. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;347:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORR-URTREGER A., GOLDNER F.M., SAEKI M., LORENZO I., GOLDBERG L., DE BIASI M., DANI J.A., PATRICK J., BEAUDET A.L. Mice deficient in the α7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor lack α-bungarotoxin binding sites and hippocampal fast nicotinic currents. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9165–9171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09165.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAULY J.R., MARKS M.J., GROSS S.D., COLLINS A.C. An autoradiographic analysis of cholinergic receptors in mouse brain after chronic nicotine treatment. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1991;258:1127–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENG X., GERZANICH V., ANAND R., WANG F., LINDSTROM J. Chronic nicotine up-regulates α3 and α7 acetylcholine receptor subtypes expressed by the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;51:776–784. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENG X., GERZANICH V., ANAND R., WHITING P.J., LINDSTROM J. Nicotine-induced increase in neuronal nicotinic receptors results from a decrease in the rate of receptor turnover. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994a;46:523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENG X., KATZ M., GERZANICH V., ANAND R., LINDSTROM J. Human α7 acetylcholine receptor: cloning of the α7 subunit from the SH-SY5Y cell line and determination of pharmacological properties of native receptors and functional α7 hopmomers expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994b;45:546–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUIK M., CHOMERIS J., KOMOURIAN J., LUKAS R.J., PUCHACZ E. Similarity between rat brain nicotinic α-bungarotoxin receptors and stably expressed α-bungarotoxin binding sites. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:145–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUIK M., GEERSTEN S., TRIFARO J.M. Marked up-regulation of the αbungarotoxin site in adrenal chromaffin cells by specific nicotinic antagonists. Mol. Pharmacol. 1987;31:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIDLEY D.L., WONNACOTT S. Modulation of α7- and α3-containing nicotinic receptor expression in SH-SY5Y cells and primary hippocampal neurones. Soc. Neurosci. 1998;24:331.5. [Google Scholar]

- ROGERS A., WONNACOTT S. Differential upregulation of α7 and α3 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal and PC12 cell cultures. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1997;25:544s. doi: 10.1042/bst025544s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROLE L.W., BERG D.K. Nicotinic receptors in the development and modulation of CNS synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROWELL R.P., LI M. Dose-response relationship for nicotine-induced up-regulation of rat brain nicotinic receptors. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:1982–1989. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68051982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SÉGUÉLA P., WADICHE J., DINELEY-MILLER K., DANI J.A., PATRICK J.W. Molecular cloning, functional properties and distribution of rat brain α7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARPLES C.G.V., KAISER S., SOLIAKOV L., MARKS M.J., COLLINS A.C., WASHBURN M., WRIGHT E., SPENCER J.A., GALLAGHER T., WHITEAKER P., WONNACOTT S. UB-165: A novel nicotinic agonist with subtype selectivity implicates the α4β2* subtype in the modulation of dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2783–2791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02783.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOKUMISTO H., CHIJIWA T., HAGIWARA M., MIZUTANI A., TERASAWA M., HIDAKA H. KN-62, 1-[N, O-Bis(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-N-methyl L-tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine, a specific inhibitor of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:4315–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHAN P.F.T., KAYE D.F., REEVE H.L., BALL S.G., PEERS C. Nicotinic receptor-mediated release of noradrenaline in the human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:2159–2166. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG F., GERZANICH V., WELLS G., ANAND R., PENG X., KEYSER K., LINDSTROM J. Assembly of human neuronal nicotinic receptor α5 subunits with α3, β2 and β4 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:17656–17685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG F., NELSON M.E., KURYATOV A., OLALE F., COOPER J., KEYSER K., LINDSTROM J. Chronic nicotine treatment up-regulates human α3β2 but not α3β4 acetylcholine receptors stably transfected in human embryonic kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:28721–28732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.28721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITEAKER P., SHARPLES C.G.V., WONNACOTT S. Agonist induced up-regulation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in M10 cells: pharmacological and spatial definition. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:950–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WONNACOTT S. The paradox of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor upregulation by nicotine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1990;11:216–219. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90242-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG X., GONG Z.-H., HELLSTRÖM-LINDAHL E., NORDBERG A. Regulation of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in M10 cells following treatment with nicotinic agonists. NeuroReport. 1995;6:313–317. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199501000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZOLI M., LÉNA C., PICCIOTTO M.R., CHANGEUX J.-P. Identification of four classes of brain nicotinic receptors using β2 mutant mice. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:4461–4472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04461.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]