The introduction of the cerebrospinal fluid shunt led to a fourfold increase in survival of babies with open spina bifida in the United Kingdom.1 In 1963 a prospective independent review was set up to record the results and implications of the new treatment.2,3 Such data are crucial to the dilemmas associated with termination of affected pregnancies or treatment at birth.4 We investigated survival, disability, health, and lifestyles in a complete cohort of adults with spina bifida.

Participants, methods, and results

Between 1963 and 1971, 117 babies had their backs closed at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, without any attempt at selection. Before closure of the back each baby had a full neurological examination. When necessary, hydrocephalus was controlled by the insertion of a ventriculoatrial shunt. In spring 2002 we reviewed the cohort by confidential postal questionnaire backed by a telephone call to the patient or carer. The Office for National Statistics provided information on deaths.

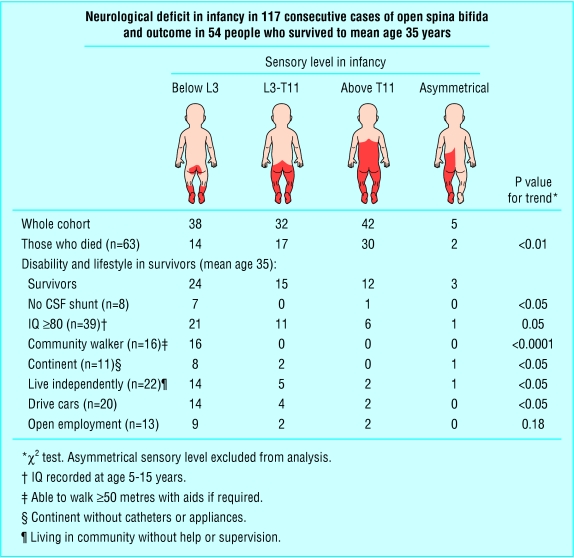

Ascertainment was 100%. Sixty three (54%) had died, mainly the most affected. Causes of death were cardiorespiratory (19) or renal (18) failure, hydrocephalus (10), central nervous system infection (10), convulsions (2), inhaled vomit (2), sudden infant death (1), and thrombocytopenic purpura (1). The mean age of the survivors was 35 years (range 32-38). The male:female ratio was 1:1.3, the same as at birth. Of the 54 survivors, 46 had a cerebrospinal fluid shunt, 39 had an IQ ≥ 80, 16 could walk 50 metres or more with or without aids, and only 11 were fully continent. Thirty had had pressure sores, and 30 were overweight. Mortality and disability were related to neurological deficit (figure).

Figure 1.

In terms of lifestyle, 22 survivors lived independently in the community, though seven depended on a wheelchair. They managed their own lives including transport, continence care, pressure areas, and all medical needs. Twelve lived in sheltered accommodation, where help was available if required, and 20 needed daily help, mainly from a parent (now aged 52-77) or partner or from social services. All these 20 were severely disabled: two were blind after shunt dysfunction, and two were on respiratory support. However 20 of the survivors drove cars, although a further nine had given up driving. Thirteen worked in open employment, five of them in wheelchairs. Seven women and two men had had a total of 13 children, none of whom had visible spina bifida.

Comment

The outcome in this complete and unselected cohort ranged from apparent normality to severe disability. This reflected both the neurological deficit in terms of sensory level in infancy and the adverse events in the history of the shunt.5 Over one third of survivors continued to need daily care.

The community basis provides a fuller perspective than hospital based studies. Only a third of the survivors were still attending a hospital. Most were in the care of general practitioners, who had to manage problems associated with incontinence, pressure sores, sepsis, epilepsy, urinary and respiratory infections, hypertension, and obesity in addition to psychological distress or backache in the carer. Doctors need to know that headache, neck ache, drowsiness, deterioration in vision, or new eye signs may indicate shunt insufficiency, which requires prompt intervention to prevent serious long term consequences.5 The continuing needs of the large number of adult patients surviving from the era of non-selective treatment will have to be dealt with for many years. Given the limited benefits of treatment, the data we have gathered from this cohort provide those involved with counselling famillies affected by spina bifida with the clinical evidence to help them to make informed decisions.

We thank the patients and their carers.

Contributors: GMH had the idea, designed the study, and is guarantor. PO helped with analysis and writing the report.

Funding: Association for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus (ASBAH). The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Cambridge LREC (reference 02/105).

References

- 1.Laurence K. Effect of early surgery for spina bifida on survival and quality of life. Lancet 1974;i: 301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt GM, Lewin L, Gleave J, Gairdner D. Predictive factors in open myelomeningocele with special reference to sensory level. BMJ 1973;iv: 197-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt GM, Poulton A. Open spina bifida: a complete cohort reviewed 25 years after closure. Dev Med Child Neurol 1995;37: 19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith GK, Smith ED. Selection for treatment in spina bifida cystica. BMJ 1973;iv: 189-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt GM, Oakeshott P, Kerry S. Link between the CSF shunt and achievement in adults with spina bifida. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;67: 591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]