Abstract

The ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel links cell metabolism to membrane excitability. Intracellular ATP inhibits channel activity by binding to the Kir6.2 subunit of the channel, but the ATP binding site is unknown. Using cysteine-scanning mutagenesis and charged thiol-modifying reagents, we identified two amino acids in Kir6.2 that appear to interact directly with ATP: R50 in the N-terminus, and K185 in the C-terminus. The ATP sensitivity of the R50C and K185C mutant channels was increased by a positively charged thiol reagent (MTSEA), and was reduced by the negatively charged reagent MTSES. Comparison of the inhibitory effects of ATP, ADP and AMP after thiol modification suggests that K185 interacts primarily with the β-phosphate, and R50 with the γ-phosphate, of ATP. A molecular model of the C-terminus of Kir6.2 (based on the crystal structure of Kir3.1) was constructed and automated docking was used to identify residues interacting with ATP. These results support the idea that K185 interacts with the β-phosphate of ATP. Thus both N- and C-termini may contribute to the ATP binding site.

Keywords: ATP/cysteine-scanning/electrostatics/Kir6.2/potassium channel

Introduction

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels play pivotal roles in many physiological processes by coupling the metabolic state of the cell to the electrical activity of the plasma membrane. They are involved in functions as diverse as glucose-dependent insulin secretion, neuronal glucose sensing, the response to cardiac ischaemia, the regulation of vascular smooth muscle tone and seizure protection (Ashcroft and Gribble, 1998; Miki et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001; Seino and Miki, 2003). The pore of the KATP channel is assembled from four identical Kir6.2 (or Kir6.1) subunits, each of which is associated with a much larger regulatory subunit known as the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) (Aguilar Bryan et al., 1995; Clement et al., 1997). Kir6.2 belongs to the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) channel family (Inagaki et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1995) and binding of ATP to Kir6.2 closes the channel (Tucker et al., 1997, 1998; Tanabe et al., 1999, 2000).

Where does Kir6.2 bind ATP? The answer to this question has proved surprisingly elusive. Although it is accepted that there are four independent ATP binding sites per KATP channel, with ATP binding to one site being sufficient to close the channel (Markworth et al., 2000; Vanoye et al., 2002), their exact location is undetermined. Because ATP only inhibits the channel from the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, and inhibition shows little voltage sensitivity, it appears that the nucleotide interacts with the cytosolic N- and/or C-terminus of Kir6.2. No obvious nucleotide binding consensus sequence is found in either of these domains, suggesting that the channel may possess a novel type of ATP binding site. In support of this idea, it has been shown that Mg2+ is not required for ATP to inhibit the channel (Gribble et al., 1998), that the site is highly selective for the adenine moiety (Tucker et al., 1998) and that large groups can be added to the end of the phosphate chain of ATP without impairing its inhibitory potency (Tanabe et al., 2000).

Photoaffinity labelling with 8-azido-[γ32P]ATP or [γ32P]ATP-γ-4-azidoanilide first provided proof that ATP binds directly to Kir6.2 (Tanabe et al., 1999, 2000). More recently, Vanoye and colleagues (Vanoye et al., 2002) demonstrated that the C-terminus of Kir6.2, fused to the maltose binding protein, binds the fluorescent ATP analogue TNP-ATP, whereas the N-terminus does not. This suggests that the principal residues contributing to the ATP binding site lie in the C-terminus of the protein. However, mutations within both the N- and C-terminal domains of Kir6.2 reduce the inhibitory potency of ATP (Shyng et al., 1997; Tucker et al., 1997, 1998; Drain et al., 1998; Trapp et al., 1998a; Koster et al., 1999; Proks et al., 1999; Reimann et al., 1999). Conceivably, such mutations could alter the affinity of ATP binding, or the transduction of binding into channel closure or the ability of the channel to shut. Indeed, mutation of residues at the end of TM2, and in the adjacent region of the C-terminus, has marked effects on channel gating, which may be sufficient to account for the reduced ATP sensitivity (Trapp et al., 1998a). Even when a mutation also abolishes 8-azido-[γ32P]ATP binding (Tanabe et al., 1999), it does not imply that the mutated residue directly interacts with ATP as it is possible that structural changes induced by the mutation have an allosteric effect on a nucleotide binding site elsewhere in the protein.

In the work reported in this paper, we have combined a cysteine substitution approach with the introduction of charges by thiol modification to probe the architecture of the ATP binding site. Thiol reagents bind irreversibly to cysteine residues and provide a means of introducing either a positive charge [methanethiosulfonate ethylamine (MTSEA)] or a negative charge [methanethiosulfonate ethylsulfonate (MTSES)] into the protein. We assume that if the ATP binding site lies sufficiently close to the modified cysteine, the introduced charge will exert an electrostatic effect on ATP binding and thus on the ability of ATP to close the channel. Thus, by examining the ATP sensitivity of cysteine-mutant channels before and after modification and comparing the effects of introduction of a positive or a negative charge, we can map the ATP binding site. Molecular modelling of the C-terminal domain of Kir6.2, based on the recent X-ray structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002) was then used to provide independent confirmation that key residues identified in functional studies could form part of an ATP binding site.

Results

Effects of thiol modification

Figure 1A and B shows that the wild-type KATP channel (Kir6.2/SUR1) is irreversibly blocked by both MTSEA and MTSES. Although MTSES (10 mM) only produced a 50% reduction in channel activity, the remaining current was unaffected by MTSEA (data not shown), indicating that all channels had already reacted with MTSES. Consequently, one or more endogenous cysteines must be modified by both positively and negatively charged MTS reagents. The block of inward KATP currents by MTSEA was very substantially reduced by mutation of C42 in Kir6.2 to alanine (C42A) (Figure 1C and D), as was previously found for the thiol reagents pCMPS (Trapp et al., 1998b) and MTSET (Cui and Fan, 2002). This suggests that all three thiol reagents modify channel activity by interacting with the same single cysteine residue at position 42 of Kir6.2. MTSES modification produced only a partial block of the wild-type channel. Inhibition was less for the C42A mutant channel but the reduction was not significant (Figure 1D). However, the fact that application of MTSES to the wild-type channel prevented subsequent modification with MTSEA strongly suggests that MTSES also interacts with residue C42 but that thiol modification does not cause complete block of the channel. Therefore we used the Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1 channel as a background for cysteine scanning mutagenesis.

Fig. 1. Thiol reagents inhibit wild-type KATP currents by interaction with C42. (A–C) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to a series of voltage ramps from –110 to +100 mV from inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes coinjected with mRNA encoding SUR1 and wild-type or mutant Kir6.2. Thiol reagents and ATP were applied to the intracellular membrane surface as indicated. (D) Mean effects of thiol reagents on KATP currents (n = 3–5). The slope conductance (G) is expressed as a fraction of the mean (Gc) of that obtained in control solution before and after application of the reagent. ** p < 0.01 compared with control solution; ++ p < 0.01 compared with Kir6.2/SUR1 currents in the same solution.

It is noteworthy that MTSEA produced a rapidly reversible voltage-dependent block of outward Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1 currents (Figure 1C). This suggests that the positively charged MTSEA molecule is small enough to enter the pore of Kir6.2 and is driven there by membrane depolarization. A similar voltage-dependent block of outward currents by MTSEA has also been observed for Kir2.1 (Lu et al., 1999).

Because Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1 currents run down in excised patches (compare Figure 1A and C), it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between rundown and a slow inhibitory effect of the thiol reagent. Therefore we attempted to control for rundown by expressing the extent of the block as a fraction of the mean of the current in the control solution before and after application of the thiol reagent (Figure 1D). However, this protocol means that any decrease in the rate of rundown during the experiment could lead to an apparent enhancement of the block, which might explain why thiol inhibition did not appear to be abolished completely by mutation of C42.

A different strategy to control for rundown was used in Figure 2. Here, we compared the mean conductance immediately prior to application of thiol reagent (Gt2/Gt1, rundown) with that in the presence of MTSEA or MTSES (Gt3/Gt2, reagent effect) and with that after removal of the drug (Gt4/Gt2, recovery). In the first two cases, the conductance at the end of a 20 s interval is expressed as a fraction of that at the beginning. Thus rundown is indicated if the conductance in the control solution falls below unity, and any significant difference in this value (labelled ‘rundown’ in Figure 2B) from that labelled ‘reagent effect’ indicates that the presence of the thiol reagent affects the current through the channel. If the relative conductance following thiol removal (labelled ‘recovery’) is significantly different from that before thiol application (labelled ‘rundown’), then thiol modification has occurred. Figure 2B demonstrates that MTSEA has no significant irreversible effect on Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1, but that MTSES may cause a small block of the channel that is not completely reversible.

Fig. 2. Effect of thiol reagents on KATP channel mutants. (A) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to a series of voltage ramps from –110 to +100 mV from inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes coinjected with mRNA encoding SUR1 and mutant Kir6.2. Thiol reagents were applied to the intracellular membrane surface as indicated. The annotations t1–t4 in panel (c) indicate time points for data analysis (see text) and lie below the relevant trace. (B) Effects of the thiol reagents MTSEA (2.5 mM, above) or MTSES (10 mM, below) on wild-type and mutant channels. Mean relative conductance (G/Gc = Gt2/Gt1) after 20 s of rundown immediately prior to application of thiol reagent (white bars), mean relative conductance (G/Gc = Gt3/Gt2) in MTSEA or MTSES (black bars) and mean relative conductance (G/Gc = Gt4/Gt2) after removal of the drug (recovery) (grey bars) for the Kir6.2 mutants indicated (n = 3–14). The broken line indicates the appropriate control conductance level. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, both compared with rundown (white bar).

We next individually mutated to cysteine each residue between N48 and R54 in the N-terminus of Kir6.2, and between R176 and A187 in the C-terminus. These regions have previously been identified as important for ATP inhibition (Tucker et al., 1997; 1998; Drain et al., 1998). All mutations, with the exception of R177C, A178C, T180C, L181C and F183C, produced functional channels when coexpressed with SUR1. Figure 2 shows the effects of the thiol reagents MTSEA and MTSES on control (Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1) and mutant channels. For each channel, we show the extent of rundown observed in control solution, the extent of block by the thiol reagent and the extent of recovery of current after removal of the agent. The data show that residues N48C, I49C G53C, E179C and H186C were unaffected by both reagents, that R50C, I182C, K185C and A187C were unaffected by MTSEA (but not MTSES) and that E51C was unaffected by MTSES (but not MTSEA). It is unclear whether thiol reagents do not interact with these residues or whether thiol modification simply has no functional effect. MTSEA unmistakably modified residues E51C, R54C and S184C, and MTSES modified residues R50C, Q52C, R54C, R176C and S184C, as indicated by the irreversible block of KATP currents. In addition, MTSEA produced an activation of R176C that was partially reversible. In contrast, MTSES caused irreversible activation of I182C. Therefore all these residues must be accessible to the bath solution.

Although some currents were significantly reduced by thiol reagents, in most cases the remaining currents were large enough for subsequent analysis of ATP sensitivity. The exceptions were E51C, R54C and I182C after MTSEA exposure, and R54C and R176C after MTSES.

Effects of thiol modification on ATP sensitivity

Figure 3A shows the effects of 1 mM ATP on control and mutant channels before and after modification with MTSEA or MTSES. The ATP sensitivity of Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1 currents was similar to that of the wild-type channel (Kir6.2/SUR1) (Trapp et al., 1998b) and was unaffected by prior exposure to either MTSES or MTSEA, suggesting that C42 is not involved in ATP inhibition and that thiol modification of other native cysteines in Kir6.2 or SUR1 (accessible to the intracellular solution) does not affect ATP sensitivity. Introduction of a cysteine at residues 49, 50, 53, 179, 182 and 185, on the Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1 background, produced a substantial reduction in ATP sensitivity but had little effect at other positions. A smaller, but still significant, reduction in ATP sensitivity was observed for residues 51, 54 and 187. Those mutants that were more than 80% inhibited by 1 mM ATP were also exposed to 0.1 mM ATP (Figure 3B). This revealed that mutation of residue 184 to cysteine slightly reduces ATP sensitivity and that Q52C is actually more ATP sensitive than the control channel. The change in nucleotide sensitivity produced by some mutations may be mediated indirectly, or it may indicate that these residues are directly involved in ATP binding. To address this question, we compared the ATP sensitivity of the mutant channels before and after thiol modification. This revealed that neither MTSEA nor MTSES significantly altered the ability of ATP to block I49C, Q52C, G53C, E179C or A187C channels. The ATP sensitivity of E51C and I182C was not affected by MTSES, whilst MTSEA irreversibly blocked the currents, thus preventing analysis of ATP sensitivity after modification. The opposite was observed for R176C. In contrast, MTSEA increased the ATP sensitivity of the R50C, S184C, K185C and H186C channels, suggesting that addition of a positive charge at these positions may enhance ATP binding. The fact that modification with the negatively charged MTSES had the opposite effect, and reduced the ATP sensitivity of these channels, supports the idea that these residues lie close to the ATP binding site.

Fig. 3. Mean response to ATP of mutant KATP channels before and after thiol modification. Mean conductance (G) in the presence of (A) 1 mM ATP or (B) 0.1 mM ATP expressed relative to that in control solution (Gc) before (black bars) and after thiol modification with MTSEA (white bars) or MTSES (grey bars). Kir6.2 mutants were coexpressed with SUR1 (n = 3–10). Missing bars, not tested. Significance was tested with the Mann–Whitney test, except for residues S184 and H186 where the paired t-test was used. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared with the ATP sensitivity of the control channel (Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1). + p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01 compared with the ATP sensitivity before modification.

The observation that a positive charge at position 50 is essential for ATP inhibition, whereas the presence of a charged group on the adjacent residue at position 51 does not influence ATP sensitivity, suggests that the side-chain of E51 (which is negatively charged in the wild-type channel) may face in the opposite direction to that of R50. Interestingly, although introduction of a positive charge at residue 48 had no effect on ATP sensitivity, a negative charge in this position strongly reduced ATP inhibition. One explanation for this finding is that addition of a negative charge at position 48 effectively neutralizes the positive charge at R50, thereby decreasing ATP sensitivity, whereas a positive charge does not provide substantially greater electrostatic attraction. Whatever the reason, the results indicate that N48 faces in the same direction as R50. The side-chains of neighbouring residues S184, K185 and H186 in the C-terminus also appear to face in the same direction because modification of all three residues produced effects on ATP sensitivity. In fact, modification of S184C or H186C with MTSEA increased the ATP sensitivity beyond that of the control channel, suggesting that increasing the charge in this region beyond that contributed by K185 enhances the ATP affinity.

Owing to the strong inhibitory effect of MTSEA and MTSES on R54C currents, it was not possible to determine the ATP sensitivity of this mutant after thiol modification. In contrast, the thiol reagent pCMPS (50 µM) did not cause pronounced inhibition of R54C currents although it prevented subsequent inhibition by MTSEA or MTSES, indicating that it had indeed reacted with the channel. After pCMPS modification of R54C, 1 mM ATP blocked KATP currents by 91 ± 3% (n = 4), which was not significantly different from that prior to thiol modification (95 ± 1%, n = 10). Thus the side-chain of R54 does not make charge–charge interactions with ATP.

Residues interacting with β- and γ-phosphates of ATP

Our results are consistent with residues R50, S184, K185 and H186 being located close to a negatively charged part of the ATP molecule where they influence ATP binding electrostatically. Two of these residues (R50 and K185) are positively charged in the wild-type channel and therefore could interact directly with the phosphate tail of ATP. To determine whether R50 and K185 lie close to the α-, β- or γ-phosphate, we compared the effects of ADP and AMP with those of ATP. Figure 4 shows that the inhibitory effect of 1 mM ADP was strongly reduced for both K185C and R50C (see also Koster et al., 1999). Modification with MTSEA restored the ADP sensitivity of K185C channels to the same extent as observed for ATP. However, AMP inhibition was unchanged. This provides strong support for the idea that K185 lies close to the β-phosphate of the ATP molecule. In contrast, MTSEA modification of R50C channels restored ADP sensitivity less effectively than ATP sensitivity, which suggests that R50 is located close to the γ-phosphate of ATP.

Fig. 4. Inhibitory effects of ADP and AMP on K185C and R50C channels before and after thiol modification. (A) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to voltage ramps from –110 to +100 mV for R50C and K185C mutant channels. (B) Mean effects of 1 mM ATP, ADP and AMP on KATP currents (n = 5–10) before (white bars) and after (black bars) modification with MTSEA. The slope conductance (G) is expressed as a fraction of the mean (Gc) of that obtained in control solution before and after application of the nucleotide. ** p < 0.01 compared with the control solution. All experiments were carried out in the absence of Mg2+ to avoid the stimulatory effect of MgADP that is mediated by the SUR subunit (Gribble et al., 1997b).

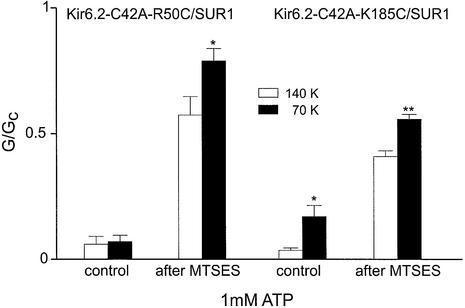

Further evidence for an electrostatic interaction between the phosphate tail of ATP and the side-chains of R50 and K185 is provided by experiments carried out at reduced ionic strength (Figure 5). When intracellular K+ was reduced to 70 mM, modification of residues 50 or 185 by MTSES resulted in less channel inhibition by 1 mM ATP than observed in 140 mM K+ solution. This is consistent with the view that the negative charge of MTSES is screened less completely in a solution of lower ionic strength and is therefore more effective at preventing access of ATP to its binding site.

Fig. 5. Inhibitory effect of ATP before and after MTSES modification in low ionic strength. Mean effects of 1 mM ATP on KATP currents (n = 4–6) in intracellular solution containing 140 mM K (white bars) or 70 mM K (black bars) before and after modification with MTSES. The slope conductance (G) is expressed as a fraction of the mean (Gc) of that obtained in control solution before and after application of the nucleotide. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared with 140 mM K solution. All experiments were carried out in the absence of Mg2+.

Molecular modelling

To explore further the role of K185 in ATP binding, we constructed a molecular model of the C-terminus of Kir6.2 based on the crystal structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002). These proteins share 25.9% sequence identity within the C-terminal domains. The Cα RMSD between the model and the template was 1.3 Å, which lies within the range expected for proteins sharing 25% sequence identity (0.7–2.3 Å) (Russel et al., 1997). ATP was docked with the model and in the majority of the 25 repeat dockings the nucleotide was found to bind to a pocket in the upper half of the structure (Figure 6). The docking was not biased to favour any specific residues interacting with ATP. Thus the fact that the ligand finds the same residues in most dockings is suggestive of an energy minimum on the potential energy landscape.

Fig. 6. Homology model of the C-terminus of Kir6.2. (A) Homology model of the Kir6.2 C-terminus, based on the crystal structure of Kir3.1, with docked ATP (red). The membrane is at the top of the structure and the loop on the right points into the lumen of the channel vestibule. (B) Close-up of the nucleotide binding site. Residues are shown in ball-and-stick configuration and cpk colours. The γ-phosphate points into the region where the partially resolved N-terminus runs in the crystal structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida and Mackinnon, 2002).

The model shows that the α-phosphate of ATP does not interact with any specific residue but faces F333 and G334. This may explain why mutation of G334 to aspartate markedly decreases ATP sensitivity (Drain et al., 1998), as it would be expected to impede nucleotide binding both sterically and electrostatically. Experimentally, we observed that addition of the negatively charged MTSES to S184C decreased the channel ATP sensitivity (Figure 3A). In our model, residue 184 lies only ∼4.2 Å away from the α-phosphate of ATP, so that increasing the length of the side-chain by addition of MTSES might be expected to cause electrostatic repulsion of the nucleotide and impair binding. The β-phosphate of ATP is oriented towards K185, and both the oxygen and the β-phosphate are within hydrogen-bonding distance of K185. Thus the model provides independent conformation that K185 interacts with the β-phosphate of ATP. The γ-phosphate of ATP does not interact with any residue in the C-terminus. Instead, it lies outside the bulk of the protein. Thus it seems feasible that it interacts with R50, which cannot be modelled as it lies within a region of the N-terminus that was unresolved in the crystal structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002).

Discussion

Our results show that the presence of a positive charge at residues 50, 184, 185 and 186 or Kir6.2 enhances nucleotide block, whereas the presence of a negative charge decreases nucleotide block. Two of these residues, R50 and K185, are positively charged in the wild-type channel. While we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the effects of thiol modification are allosteric, we believe that the evidence favours the idea that the modified residues lie close to the bound nucleotide, and that R50 and K185 interact directly with ATP. This is because MTSEA modification of R50C channels increases inhibition by ATP much more effectively than that by ADP or AMP, and modification of K185C increases inhibition by ATP and ADP but not by AMP. If we assume that R50 lies not at the nucleotide binding site but in the transduction pathway, it is difficult to imagine how ATP and ADP inhibition could be affected differentially. Thus the simplest explanation is that ATP interacts directly with R50 and K185. Our data further suggest that R50 primarily interacts with the γ-phosphate of ATP, whereas K185 interacts specifically with the β-phosphate. Additional support for this idea comes from our model of the C-terminus of Kir6.2 where ATP, when randomly docked into the structure, repeatedly binds to a pocket containing K185 and lies within hydrogen-bonding distance of the β-phosphate.

Therefore, taken together, our results are consistent with the idea that the side-chains of residues R50, S184, K185 and H186 lie within a few ångströms of the phosphate tail of the bound ATP molecule. In contrast, the side-chains of neighbouring residues are unlikely to approach the phosphate tail of the ATP molecule as closely because the addition of a positive or negative charge did not influence ATP inhibition. Thus the ATP binding site contains contributions from both the N- and C-termini of Kir6.2.

Effects of thiol reagents

MTSEA and MTSES decreased the current amplitude of both the control (Kir6.2-C42A/SUR1) and many mutant channels. As noted above, it is difficult to distinguish a slow block of the channel by the thiol reagent from slight changes in the rate of rundown. Therefore we only discuss here those mutations that confer an irreversible sensitivity to thiol reagents that is significantly different in magnitude from that of the control channel. An increased block (or activation) by one or both thiol reagents was observed with the mutants R50C, E51C, Q52C, R54C, R176C, I182C and S184C, indicating that the side-chains of these residues must be accessible from the bath solution (i.e. the cytoplasmic side of the membrane). Because ATP sensitivity is altered after application of the thiol reagents, residues N48, K185 and H186 must also be accessible. However, residues I49, Q52, E179 and A187 may not be accessible as the current amplitude (with or without ATP) was not significantly altered by thiol reagents. The mechanism of block must first involve interaction of the thiol reagent with the introduced cysteine, but could then be mediated by either an allosteric inhibition of channel activity or the tethered thiol reagent entering the intracellular entrance of the pore and blocking the permeation pathway. Recently, Cui and Fan (2002) have shown that thiol block of the wild-type channel at C42 is produced by an allosteric effect. However, channel inhibition by thiol modification of residues I210, I211 and S212 may result from plugging of the channel pore by the bulky reagent (Cui et al., 2002).

It is noteworthy that for most residues the inhibitory effect of thiol reagents was charge independent, with both MTSEA and MTSES reducing the KATP currents, which means that block is not due to an electrostatic effect on channel gating. Remarkably, however, the negatively charged reagent MTSES irreversibly blocked R176C and produced a dramatic and irreversible increase in I182C currents, whereas MTSEA had the opposite effect, increasing R176C and blocking I182C currents. It has been proposed that the phospholipid phosphatidyl inositol bisphosphate (PIP2), which potentiates KATP currents and decreases their ATP sensitivity, interacts with R176 and R177 in the C-terminus of Kir6.2 (Fan and Makielski, 1997; Baukrowitz et al., 1998; Shyng and Nichols, 1998). The large increase in R176 currents produced by MTSEA would be consistent with the idea that the presence of a positive charge at residue R176 enhances the interaction with PIP2. Likewise, the decrease in current produced by MTSES could reflect a decreased interaction resulting from the introduction of a negative charge. Therefore, by analogy, it is possible that the negative charge introduced by MTSES modification of I182C mimics the effect of PIP2, producing maximal current activation, whereas a positive charge has the opposite effect.

Mutations affecting ATP sensitivity

Mutation of a number of residues to cysteine produced a significant reduction in channel ATP sensitivity. While these may reflect local changes in the ATP binding site, they could also result from global conformational changes that influence nucleotide binding allosterically or that modulate channel gating or transduction. The mutation I182C strongly reduced the channel ATP sensitivity, as previously observed for a range of other mutations at this position, including substitution with either a positive charge (K,R) or a negative charge (E) (Li et al, 2000). Single-channel analysis has shown that none of these mutations alter the channel kinetics, suggesting that I182 may influence ATP binding and/or transduction rather than gating. However, modification with a negatively charged thiol reagent had no effect on the ATP sensitivity of I182C, indicating that the phosphate tail of ATP does not approach I182 closely. In agreement, our model (Figure 6) proposes that ATP sits in a binding pocket that lies close to the membrane, with the adenine ring and the ribose sugar positioned on one side of a β-sheet and the phosphate tail on the other. This effectively separates the charged and uncharged groups. The adenine ring of ATP sits in a pseudohydrophobic pocket lined by E179, T180 and I182 on one side and the side-chain residues of A300 and T302 on the other. This explains why mutation of E179 and I182 cause marked reductions in channel ATP sensitivity (T180 did not express functional channels). The backbone oxygen atom of R301 makes non-bonded electrostatic interactions with the N1 atom in the adenine ring. Because of this interaction ITP, GTP or 8-azido-ATP do not dock to this site with high affinity in our model, in agreement with previous experimental data (Tucker et al., 1998; Tanabe et al., 1999).

Comparison with previous mutagenesis studies

Our results shed new light on previous studies in which K185 was mutated to different residues (Reimann et al., 1999). Replacement of K185 by arginine had little effect because this residue is positively charged and of similar size to lysine. Likewise, the side-chain of a lysine residue is only slightly different from that of a cysteine modified with MTSEA (it is simply 2.6 Å shorter), which explains why K185C currents are as ATP sensitive as wild-type currents after modification with MTSEA. The reduction of ATP sensitivity associated with a negatively charged amino acid (glutamate or aspartate) at position 185 (Reimann et al., 1999), or following modification of K185C with MTSES, can be explained by the prevention of ATP entry to its binding site due to charge repulsion.

Uncharged residues at position 185 have intermediate but variable effects. Thus mutation of K185 to glutamine did not alter the sensitivity of ADP relative to that of ATP (Koster et al., 1999; Reimann et al., 1999) or the relative potency of ATP, GTP and ITP (Reimann et al., 1999). The results were interpreted previously to indicate that the side-chain of K185 does not interact with bound ATP, but instead points into a hydrophobic pocket in the protein that stabilizes the structure of an ATP binding site that lies elsewhere. However, the same experimental results would be expected if K185 interacted specifically with the β-phosphate of ATP, and Figures 4 and 6 demonstrate that this is indeed the case. In agreement with our results, Ribalet et al. (2003) recently reported that the K185Q mutation dramatically reduces both ADP and ATP sensitivity but leaves AMP sensitivity almost unaffected.

Whilst our results suggest that R50 lies close to the γ-phosphate of ATP, previous studies have indicated that ATP sensitivity correlates more closely with the size of the residue at this position rather than its charge, with smaller residues producing a channel that is less ATP sensitive (Proks et al., 1999). Furthermore, the R50C mutation itself markedly reduced the channel sensitivity to ADP, despite the fact that thiol modification indicates that this residue primarily interacts with the γ-phosphate of ATP. There are a number of possible explanations for these differences. One possibility is that mutation of R50 to a small amino acid, such as cysteine, reduces the channel ATP sensitivity not only by removing the electrostatic interaction with the γ-phosphate of ATP but also by subtly altering the structure of the nucleotide binding site. This structural change must be small and is probably confined to the binding pocket, because the positively charged thiol reagent MTSEA almost completely restored the ATP sensitivity of the R50C mutant. Another possibility is that the charge at R50 has an additional functional role. For example, it might influence channel gating or transduction (Babenko et al., 1999).

Mechanism of channel inhibition by ATP

Our results indicate a close apposition of the N- and C-termini of Kir6.2, and are supported by evidence from protein–protein interaction studies that the N- and C-termini physically interact, and by the X-ray structure of Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002). The N-terminal interaction domain (NID) of Kir6.2 comprises residues 30–46 (Tucker and Ashcroft, 1999) and immediately precedes R50, which according to our results coordinates the γ-phosphate of ATP. The equivalent region of the N-terminus of Kir3.1 binds to its C-terminus (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002). Three regions of the C-terminus of Kir6.2 were found to interact with the NID domain (Jones et al., 2001), one of which (residues 170–204) contains K185 which interacts with the β-phosphate of ATP. Because these biochemical studies were carried out in the absence of ATP, the cytosolic domains appear to interact in the absence of nucleotide. It seems plausible that ATP binding may modify this interaction, producing a conformational change that is transduced to the transmembrane domains and ultimately results in channel closure. Interestingly, in the crystal structure of Kir3.1, the N-terminal region containing the residue equivalent to R50 in Kir6.2 was not resolved. This suggests that this part of the structure is very flexible and could conceivably confer the ATP-dependent gating movement.

Our observation that ligand binding to Kir6.2 occurs at the interface between two domains of the protein is a feature shared with many other ion channels. For example, the ligand binding pocket of the Lymnaea ACh binding protein contains contributions from adjacent subunits (Brejc et al., 2001), residues from both the N-terminus and the loop between the second and third transmembrane helices participate in glutamate binding to glutamate receptor channels (Sun et al., 2002), and Ca2+ is located at the interface between two RCK domains in the prokaryotic K+ channel MthK (Jiang et al., 2002).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have identified two residues in Kir6.2 (R50 and K185) which appear to interact principally with the γ- and β-phosphates, respectively, of the ATP molecule. These residues lie in close proximity to a hydrophobic pocket that accommodates the adenosine moiety. The positive charges at positions equivalent to both R50 and K185 are conserved in Kir6.1, which also shows ATP sensitivity (Takano et al., 1998). However, most other Kir channels lack positive charges at both these positions, which may account, at least in part, for the fact that they do not show high-affinity ATP block. An interesting exception is Kir1.1, which has been reported to show low ATP sensitivity (McNicholas et al., 1996) and which possesses a lysine at a position equivalent to Kir185 in Kir6.2, but has a negatively charged aspartate at position 51 (equivalent to R50). It will be interesting to see to what extent these sequence differences contribute to the variability in ATP sensitivity found for Kir channels.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

Mouse Kir6.2 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number D50581) (Inagaki et al., 1995; Sakura et al., 1995) and rat SUR1 (accession number L40624) (Aguilar Bryan et al., 1995) were used in this study. Site-directed mutagenesis of Kir6.2 was performed using the altered sites II System (Promega, Southampton, UK). Wild-type and mutant cDNAs were cloned in the pBF vector, and capped mRNA was prepared using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE large-scale in vitro transcription kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), as previously described (Gribble et al., 1997a).

Electrophysiology

Xenopus laevis oocytes were isolated and injected with 0.1 ng full-length wild-type or mutant Kir6.2 and ∼2 ng of SUR1 mRNAs (giving a 1:20 ratio) as previously described (Gribble et al., 1997a). Oocytes were studied 1–4 days after injection.

Macroscopic currents were recorded from giant excised inside-out patches at a holding potential of 0 mV and 20–24°C. Currents were evoked by repetitive 3 s voltage ramps from –110 mV to +100 mV; this protocol was employed to ensure that any voltage-dependent effects of thiol reagents were detected. Currents were recorded using an EPC7 patch–clamp amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany), filtered at 0.2 kHz, digitized at 0.5 kHz using a Digidata 1200 Interface and analysed using pClamp software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA).

The pipette solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2.6 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with KOH). The internal (bath) solution contained 107 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH) and nucleotides as indicated. The Mg2+-free solution contained 107 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EDTA (free Mg2+, ∼600 nM) and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH). The low ionic strength solution contained 37 mM KCl, 140 mM sorbitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EDTA and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2 with KOH). Solutions containing nucleotides were made up freshly each day and the pH subsequently readjusted, if required. The thiol reagents MTSEA (2.5 mM) and MTSES (10 mM) were dissolved directly in the internal solution immediately prior to the experiment (Stauffer and Karlin, 1994). Rapid exchange of internal solutions was achieved by positioning the patch in the mouth of one of a series of adjacent inflow pipes placed in the bath.

Data analysis

The slope conductance was measured by fitting a straight line to the current–voltage relation between –20 mV and –100 mV; the average of five consecutive ramps was calculated in each solution. To control for rundown, we expressed the extent of inhibition by ATP as a fraction of the mean of the value obtained in the control solution before and after application of the test agent. Rundown of channel activity and the effect of thiol reagents on mutant channels were quantified as indicated in Figure 2. For rundown, the slope conductance immediately prior to application of the thiol reagent (Gt2) was expressed as a fraction of that 20 s earlier (Gt1). The effect of thiol reagents was expressed by plotting the slope conductance in the presence of the reagent (Gt3) as a fraction of that prior to modification (Gt2). Reversibility of the thiol reagent effect was assessed by plotting the slope conductance after removal of the reagent (Gt4) as a fraction of that prior to application of the reagent (Gt2). Data are given as mean ± SEM. For statistical analysis the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test or paired t-test was performed as indicated.

Molecular modelling

Comparative modelling was used to construct a molecular model of Kir6.2 based on the known crystal structure of the C-terminus of Kir3.1 (Nishida and MacKinnon, 2002). The C-terminal sequence of Kir6.2 (residues 177–359) was aligned with that of Kir3.1 using the program ClustalX. The alignment exhibited only a single sequence shift: an additional aspartic acid residue (D280) is inserted in the Kir6.2 sequence. A gap was modelled in the template sequence that corresponded to this additional residue. Several Kir6.2 models were constructed, with the final one being selected on the basis of Cα RMSD values after superimposition on the model of the Kir3.1 template. Restrained minimization did not significantly modify the model structure. Although Kir 6.2 is a homotetramer, it is known that there are four ATP binding sites and that these sites do not interact (Markworth et al., 2000); thus, for simplicity, only a monomer was modelled. ATP docking to the C-terminus was performed using the program AUTODOCK (Morris et al., 1998) followed by flexible interactive docking using a Monte Carlo simulated annealing routine within InsightII. During the latter, contact residues and the ATP itself were allowed to be flexible. Finally, a short burst of molecular dynamics on the fully solvated protein, using GROMACS (www.gromacs.org), was used to relax the side-chain conformations in the vicinity of the ATP molecule.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Michael Dabrowski, Dr Chris Miller and Dr Tim Ryder for valuable discussion, and Dr Bernd Fakler for the pBF vector. This work was supported by grants from the Royal Society and the Wellcome Trust. F.M.A is the Royal Society GlaxoSmithKline Research Professor.

References

- Aguilar Bryan L. et al. (1995) Cloning of the beta cell high-affinity sulfonylurea receptor: a regulator of insulin secretion. Science, 268, 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft F.M. and Gribble,F.M. (1998) Correlating structure and function in ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Trends Neurosci., 21, 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko A.P., Gonzalez,G. and Bryan,J. (1999) The N-terminus of Kir6.2 limits spontaneous bursting and modulates the ATP-inhibition of KATP channels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 255, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T., Schulte,U., Oliver,D., Herlitze,S., Krauter,T., Tucker,S.J., Ruppersberg,J.P. and Fackler,B. (1998) PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science, 282, 1141–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brejc K., van Dijk,W.J., Klaassen,R.V., Schuurmans,M., van der Oost,J., Smit,A.B. and Sixma,T.K. (2001) Crystal structure of an ACh-binding protein reveals the ligand-binding domain of nicotinic receptors. Nature, 411, 269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement J.P., Kunjilwar,K., Gonzalez,G., Schwanstecher,M., Panten,U., Aguilar Bryan,L. and Bryan,J. (1997) Association and stoichiometry of K(ATP) channel subunits. Neuron, 18, 827–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. and Fan,Z. (2002) Mechanism of Kir6.2 channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification: pore block or allosteric gating? J. Physiol., 540, 731–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y., Wang W. and Fan,Z. (2002) Cytoplasmic vestibule of the weak inward rectifier Kir6.2 potassium channel. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 10523–10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain P., Li,L. and Wang,J. (1998) KATP channel inhibition by ATP requires distinct functional domains of the cytoplasmic C terminus of the pore-forming subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 13953–13958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z. and Makielski,J.C. (1997) Anionic phospholipids activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J.Biol.Chem., 272, 5388–5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Ashfield,R., Ammala,C. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997a) Properties of cloned ATP-sensitive K+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol., 498, 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997b) The essential role of the Walker A motifs of SUR1 in K-ATP channel activation by MgADP and diazoxide. EMBO J., 16, 1145–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble F.M., Tucker,S.J., Haug,T. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1998) MgATP activates the b cell KATP channel by interaction with its SUR1 subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 7185–7190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N., Gonoi,T., Clement,J.P.,4th, Namba,N., Inazawa,J., Gonzalez,G., Aguilar Bryan,L., Seino,S. and Bryan,J. (1995) Reconstitution of IKATP: an inward rectifier subunit plus the sulfonylurea receptor. Science, 270, 1166–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Lee,A.L., Cadene,M., Chait,B.T. and MacKinnon,R. (2002) Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature, 417, 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P.A., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (2001) Multiple sites of interaction between the intracellular domains of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir6.2. FEBS Lett., 508, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster J.C., Sha,Q., Shyng,S. and Nichols,C.G. (1999) ATP inhibition of KATP channels: control of nucleotide sensitivity by the N-terminal domain of the Kir6.2 subunit. J. Physiol., 515, 19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Wang,J. and Drain,P. (2000). The I182 region of k(ir)6.2 is closely associated with ligand binding in K(ATP) channel inhibition by ATP. Biophys. J., 79, 841–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Nguyen,B., Zhang,X. and Yang,J. (1999). Architecture of a K+ channel inner pore revealed by stoichiometric covalent modification. Neuron, 22, 571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas C. M, Yang,Y., Giebisch,G. and Hebert,S.C. (1996) Molecular site for nucleotide binding on an ATP-sensitive renal K+ channel (ROMK2). Am. J. Physiol., 271, F275–F285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markworth E., Schwanstecher,C. and Schwanstecher,M. (2000) ATP4– mediates closure of pancreatic beta-cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels by interaction with 1 of 4 identical sites. Diabetes, 49, 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T. et al. (2001) ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the hypothalamus are essential for the maintenance of glucose homeostasis. Nat. Neurosci., 4, 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G.M., Goodsell,D.S., Halliday,R.S., Huey,R., Hart,W.E., Belew,R.K. and Olson,A.J. (1998) Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem., 19, 1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M. and MacKinnon,R. (2002) Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Cell, 111, 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P., Gribble,F.M., Adhikari,R., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1999) Involvement of the N-terminus of Kir6.2 in the inhibition of the KATP channel by ATP. J. Physiol., 514, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann F., Ryder,T.J., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1999) The role of lysine 185 in the Kir6.2 subunit of the KATP channel by ATP. J. Physiol., 520, 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribalet B., John,S.A. and Weiss,J.N. (2003) Molecular basis for Kir6.2 channel inhibition by adenine nucleotides. Biophys J., 84, 266–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russel R.B., Saqi,M.A., Sayle,R.A., Bates,P.A. and Sternberg,M.J. (1997) Recognition of analogous and homologous protein folds: analysis of sequence and structure conservation. J. Mol. Biol., 269, 423–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H., Ammala,C., Smith,P.A., Gribble,F.M. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1995) Cloning and functional expression of the cDNA encoding a novel ATP-sensitive potassium channel subunit expressed in pancreatic beta-cells, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett., 377, 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S. and Miki,T. (2003). Physiological and pathophysiological roles of ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol., 81, 133–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S.L. and Nichols,C.G. (1998). Membrane phospholipids control of nucleotide sensitivity of KATP channels. Science, 282, 1138–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shyng S.L., Ferrigni,T. and Nichols,C.G. (1997) Control of rectification and gating of cloned KATP channels by the Kir6.2 subunit. J. Gen. Physiol., 110, 141–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer D.A. and Karlin,A. (1994) Electrostatic potential of the acetylcholine binding sites in the nicotinic receptor probed by reactions of binding-site cysteines with charged methane thiosulfonates. Biochemistry, 33, 6840–6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Olson,R., Horning,M., Armstrong,N., Mayer,M. and Gouaux,E. (2002) Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature, 417, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano M., Xie, L-H., Otani,H. and Horie,M. (1998) Cytoplasmic terminus domains of Kir6.x confer different nucleotide-dependent gating on the ATP-sensitive K+ channel. J.Physiol., 512, 395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K., Tucker,S.J., Matsuo,M., Proks,P., Ashcroft,F.M., Seino,S., Amachi,T. and Ueda,K. (1999) Direct photoaffinity labeling of the Kir6.2 subunit of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel by 8-azido-ATP. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 3931–3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K., Tucker,S.J., Ashcroft,F.M., Proks,P., Kioka,N., Amachi,T. and Ueda,K. (2000) Direct photoaffinity labeling of Kir6.2 by [γ-32P]ATP-[γ]4-azidoanilide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 272, 316–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S., Proks,P., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1998a) Molecular analysis of ATP-sensitive K channel gating and implications for channel inhibition by ATP. J. Gen. Physiol., 112, 333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S., Tucker,S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1998b) Mechanism of ATP-sensitive K channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification. J. Gen. Physiol., 112, 325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S.J. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1999) Mapping of the physical interaction between the intracellular domains of an inwardly rectifying potassium channel, Kir6.2. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 33393–33397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S.J., Gribble,F.M., Zhao,C., Trapp,S. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1997) Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature, 387, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker S.J., Gribble,F.M., Proks,P., Trapp,S., Ryder,T.J., Haug,T., Reimann,F. and Ashcroft,F.M. (1998) Molecular determinants of KATP channel inhibition by ATP. EMBO J., 17, 3290–3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoye C.G., MacGregor,G.G., Dong,K., Tang,L., Buschmann,A.S., Hall,A.E., Lu,M., Giebisch,G. and Hebert,S.C. (2002) The carboxyl termini of KATP channels bind nucleotides. J.Biol.Chem., 277, 23260–23270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Ji,J.J., Yuan,H., Miki,T., Sato,S., Horimoto,N., Shimizu,T., Seino,S. and Inagaki,N. (2001) Protective role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in hypoxia-induced generalized seizures. Science, 292, 1543–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]