Abstract

PrP knockout mice with disruption of only the PrP-encoding region (Zürich I-type) remain healthy, whereas mice with deletions extending upstream of the PrP-encoding exon (Nagasaki-type) suffer Purkinje cell loss and ataxia, associated with ectopic expression of Doppel in brain, particularly in Purkinje cells. The phenotype is abrogated by co-expression of full-length PrP. Doppel is 25% similar to PrP, has the same globular fold, but lacks the flexible N-terminal tail. We now show that in Zürich I-type PrP-null mice, expression of N-terminally truncated PrP targeted to Purkinje cells also leads to Purkinje cell loss and ataxia, which are reversed by PrP. Doppel and truncated PrP probably cause Purkinje cell degeneration by the same mechanism.

Keywords: cerebellar syndrome/Doppel protein/L7 promoter/prion protein/Purkinje cell loss

Introduction

The prion protein (PrP) plays a central role in the pathogenesis of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) such as Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) or bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) (Prusiner, 1996; Weissmann et al., 1996; Prusiner et al., 1998; Weissmann, 1999). Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie and fail to propagate prions (Büeler et al., 1993; Manson et al., 1994b; Sailer et al., 1994; Sakaguchi et al., 1995); introduction of PrP-encoding transgenes restores susceptibility to the disease (Fischer et al., 1996). The cellular form of the prion protein, PrPC, is encoded by a single-copy gene (Basler et al., 1986). It is attached by a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor to the outer cell surface and is found mainly in the brain, at neuronal synapses (Sales et al., 1998). PrPC comprises a globular domain consisting of three α-helices, one short antiparallel β-sheet and a single disulfide bond (Riek et al., 1996). The N-terminal half of the molecule is highly flexible (Donne et al., 1997; Riek et al., 1997).

Several PrP knockout mouse lines have been generated, differing in the design of the gene disruption (reviewed in Weissmann and Aguzzi, 1999). Two lines in which only the PrP-coding sequence was disrupted (Büeler et al., 1992; Manson et al., 1994a), to be referred to as ‘Zürich I-type’ mice, developed normally and remained healthy, showing only minor electrophysiological deficits (Collinge et al., 1994; Colling et al., 1996) and altered circadian rhythm (Tobler et al., 1996). However, three other lines with more extensive gene deletions, ‘Nagasaki-type’ PrP knockout mice, developed Purkinje cell loss followed by ataxia (Sakaguchi et al., 1996; Moore et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2001). Because the ataxic phenotype could be rescued by a PrP-encoding transgene, it originally was concluded that the phenotype was due to the absence of PrP (Sakaguchi et al., 1996; Nishida et al., 1999), although the conclusion was incompatible with the earlier reports (Weissmann, 1996).

It was found later that the ataxic phenotype of all three Nagasaki-type lines is associated with ectopic expression of the PrP-like protein Doppel (Dpl) in brain (Moore et al., 1999; Li et al., 2000a; Rossi et al., 2001). Dpl is an N-glycosylated, GPI-anchored protein (Lu et al., 2000; Silverman et al., 2000), normally expressed in a variety of tissues but not in postnatal brain (Moore et al., 1999; Li et al., 2000b). Its physiological function is still unknown, but its absence causes male sterility in mice (Behrens et al., 2002). Dpl and PrP show ∼25% sequence similarity (Moore et al., 1999), and both comprise three α-helices and one antiparallel β-sheet in a similar fold, with only minor differences (Lu et al., 2000; Silverman et al., 2000; Mo et al., 2001). Dpl is encoded by Prnd, located 16 kb downstream of the Prnp gene (Moore et al., 1999). The loss of the splice acceptor site of the PrP-encoding Prnp exon 3, a consequence of the PrP gene deletion strategy in Nagasaki-type mice, causes formation of chimeric transcripts containing the first two non-coding exons of the Prnp locus linked to the Dpl-encoding Prnd exon. This places Dpl expression under the control of the Prnp promoter (Moore et al., 1999; Li et al., 2000a). The time to onset of disease is inversely correlated with the expression level of Dpl in the brain and is rescued by co-expression of PrPC (Rossi et al., 2001). Thus, ectopic expression of Dpl in the absence of PrP, rather than the absence of PrPC in itself, causes Purkinje cell loss in Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice. Moore et al. (2001) reported that transgenic Prnpo/o mice expressing Dpl ubiquitously in brain developed severe ataxia associated with loss of both granule and Purkinje cells. The age of onset was inversely proportional to the level of Dpl expression, and 1-month-old mice were already affected (Moore et al., 2001). Introduction of a hamster PrP-encoding transgene resulted in complete abrogation of the cerebellar syndrome in mice expressing moderate levels, and partial abrogation in animals expressing high levels of Dpl. Both unaltered incubation times and pathology in brain tissue expressing PrP and Dpl upon challenge with different prion strains sustain the conclusion (Behrens et al., 2001) that Dpl is unlikely to be involved in prion pathogeneses (Moore et al., 2001; Tuzi et al., 2002).

We reported earlier that expression in PrP knockout mice of PrP lacking the flexible N-terminal tail (PrPΔ32–121 or PrPΔ32–134) gives rise to a dose-dependent phenotype comprising ataxia and loss of cerebellar granule cells, which is abrogated by co-expression of wild-type PrP (Shmerling et al., 1998). Shmerling et al. proposed that the binding of PrP to a putative ligand elicits a signal necessary for cell survival and that a functional homologue of PrP supplies this function in its absence. Expression of truncated PrP was postulated to interfere with signalling by displacing the functional homologue from the ligand without eliciting the survival signal of PrP. PrP, in turn, because of its higher affinity for the ligand, would displace its truncated counterpart and restore the signal (Shmerling et al., 1998).

Because the overall structure of Dpl is remarkably similar to that of the globular domain of PrP lacking the flexible N-terminus, the mechanism of pathogenesis might be the same in both ataxic syndromes (Moore et al., 1999; Weissmann and Aguzzi, 1999). Why, however, should truncated PrP cause degeneration of granule cells while Dpl entails Purkinje cell loss if the mechanism is the same? Perhaps it is because the ‘half-genomic’ PrP vector used to express the truncated PrP is inactive in Purkinje cells, but very active in granule cells (Fischer et al., 1996; Chiesa et al., 1998), whilst Dpl, under the control of the intact PrP promoter, is strongly upregulated in Purkinje cells and much less so in granule cells (Li et al., 2000a).

To test this hypothesis, we targeted truncated PrP specifically to Purkinje cells of Zürich I-type PrP knockout mice to determine whether the resulting phenotype would be the same as that of Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice with ectopic expression of Dpl, namely age-dependent Purkinje cell loss followed by ataxia, suppressible by a single wild-type PrP allele.

Results

Purkinje cell loss and ataxia in mice expressing the truncated PrP under the control of the L7 promoter

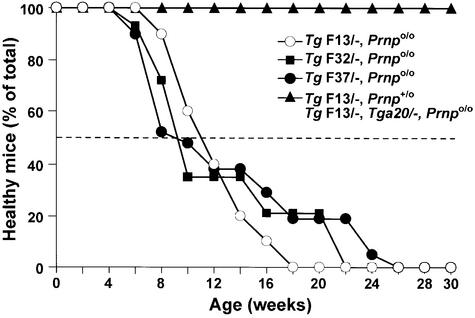

We expressed PrP devoid of residues 32–134 (PrPΔ32–134) under the control of the Purkinje cell-specific L7 promoter (Oberdick et al., 1990) in Zürich I Prnpo/o mice (Büeler et al., 1992). Three transgenic lines, TgF32, TgF37 and TgF13, were generated and analysed (Table I; Figure 1). Truncated PrP was detectable only in Purkinje cells, as judged by immunohistochemistry for PrP (Figure 2). Within the Purkinje cells, truncated PrP is highly expressed in cell bodies, axons and dendrites, as shown in 3-week-old TgF13 mice (Figures 2 and 3). Mice hemizygous for the transgene cluster on a Prnpo/o background showed the first signs of behavioural abnormalities, such as reduced exploratory activities and mild trembling gait, at ∼2 months. Mice displaying these abnormalities were scored as affected (ataxic syndrome) (Figure 1). The ataxic syndrome was present in 50% of analysed mice by ∼9–11 weeks, depending on the line (Table I). Ataxia and trembling gait increased over time, and footprint analysis revealed a similar pattern to that described for the Nagasaki-type Zürich II PrP knockout mice (Rossi et al., 2001). After ∼1 year, the general poor condition of the mice precluded further maintenance.

Table I. Zürich I PrP knockout mouse lines expressing truncated PrP (PrPΔ32–134) under the control of the Purkinje cell-specific L7 promoter.

| Name of the linea | Genotype | Transgene copy numberb | Age at onset of ataxia (weeks)c | Mice analysed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TgF32 | Prnpo/o, Tg L7-ΔPrP/– | 130 | 9 | 14 |

| TgF37 | Prnpo/o, Tg L7-ΔPrP/– | 120 | 9 | 21 |

| TgF13 | Prnpo/o, Tg L7-ΔPrP/– | 60 | 11 | 10 |

| TgF13/Prnpo/+ | Prnpo/+, Tg L7-ΔPrP/– | n.d. | >49 | 8 |

| TgF13/Tga20 | Prnpo/o, Tg L7-ΔPrP/, Tga20/– | n.d. | >70 | 11 |

aThe full designations of the lines are Prnptm1-Tg(PrPΔ134)332 Zbz for TgF32, Prnptm1-Tg(PrPΔ134)337 Zbz for TgF37, and B6D2F1-Tg(PrPΔ134)13 for TgF13.

bTransgenic copy numbers were estimated relative to standards by quantitative PCR using primers SIG and Mut217 (Shmerling et al., 1998). As standards, mouse DNA containing 30 and 40 copies of the transgene cluster PrPΔ32–80 obtained from D11 and D12 mice were used, respectively (Fischer et al., 1996). Because TgF13 mice showed the highest expression level of Purkinje cell-specific PrP and the most uniform labelling, all complementation and time course experiments were carried out with this line.

cAverage age of mice when the phenotype was present in 50% of the mice analysed. Earliest onset and 100% morbidity were different for each line, as shown in Figure 1.

n.d., not done.

Fig. 1. Age at onset of ataxic syndrome in mice expressing the truncated PrP (PrPΔ32–134) under the control of the Purkinje cell-specific L7 promoter. Hemizygous mice (L7-ΔPrP/–) of the lines TgF13 (n = 10), TgF32 (n = 14) and Tg37 (n = 21) were assessed at 2-week intervals for behavioural abnormalities, such as reduced exploratory activities, trembling gait and ataxia. Mice displaying these abnormalities were scored as affected. This syndrome was present in 50% of mice analysed by ∼9 and 11 weeks of age, depending on the line (Table I). Introduction of a single wild-type allele (Prnp+) or a transgenic cluster (Tga20) into the TgF13 line abrogated the ataxic phenotype in F1 offspring (TgF13,Prnp+/o; n = 8) and (TgF13,Tga20/–,Prnpo/o; n = 11), respectively.

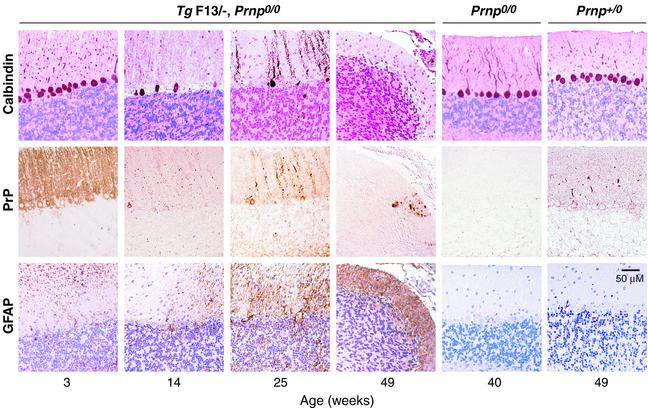

Fig. 2. Time course of Purkinje cell degeneration in Zürich I Prnpo/o mice expressing truncated PrP (PrPΔ32–134) under the control of the Purkinje cell-specific L7 promoter. Immunostaining for calbindin (top row), PrP (middle row) and GFAP (lower row) of sections through cerebella of L7-ΔPrP mice (TgF13) are shown. Sections were immunostained for PrP using R340 and TSA amplification as described in Materials and methods. GFAP and calbindin were visualized as described in Materials and methods. Three-week-old mice show normal cerebellar structure with weak gliosis. Truncated PrP is highly expressed in Purkinje cell bodies, axons and dendrites, but not in granule cells. After onset of ataxia, 14-week-old mice present with Purkinje cell loss and moderate gliosis in the molecular layer. At 25 weeks, mice show an extended Purkinje cell loss associated with moderate gliosis. In 49-week-old mice, there is an almost complete Purkinje cell loss, shrinkage of the molecular layer, decrease of granular cells and intense gliosis; a single, remaining Purkinje cell is PrP positive. Age-matched controls (Prnpo/o, Prnpo/+) show an intact Purkinje cell layer and no gliosis.

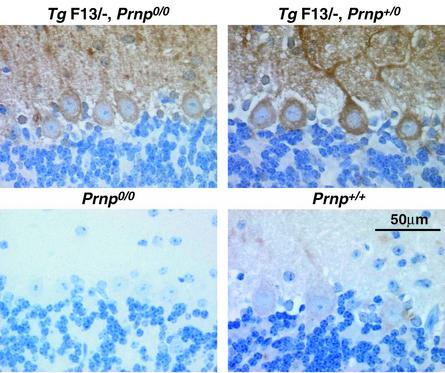

Fig. 3. Immunostaining for PrP in Purkinje cells of wild-type, PrP knockout and L7-ΔPrP transgenic mice. Cerebellar sections were immunostained for PrP using R340 and TSA amplification as described in Materials and methods. The truncated PrP is strongly overexpressed in Purkinje cell bodies, axons and dendrites of 3-week-old TgF13 mice (TgF13,Prnpo/o) in comparison with a faint staining in wild-type controls (Prnp+/+). No background staining was found in the same area of PrP knockout mice (Prnpo/o) processed in parallel with all sections shown. Introduction of a single wild-type Prnp+ allele in transgenic mice completely abrogated the ataxic phenotype. L7-ΔPrP transgene expression is not decreased in 3-week-old mice (TgF13/–,Prnpo/+) or older mice (data not shown). It is striking that the pathogenic effect of the truncated PrP at levels several times higher than PrP levels in wild-type mice is completely abolished by a single Prnp+ allele, suggesting a highly specific effect of wild-type PrP in counteracting the L7-ΔPrP-induced cell degeneration.

The TgF13 line was selected for further analysis, because it was the earliest to reach 100% morbidity (Figure 1). Moreover, TgF13 mice had the highest level of Purkinje cell-specific expression of the truncated PrP, as judged by immunohistochemistry for PrP (data not shown), and virtually all Purkinje cells were uniformly labelled by immunostaining for PrP (Figures 2 and 3). We analysed cerebellar sections of TgF13 mice for histopathological changes before and after onset of symptoms (Figure 2). At 3 weeks of age, there was marginal Purkinje cell loss associated with slight gliosis in the molecular layer, while the granular cell layer was normal. At 14 weeks, when behavioural abnormalities were present in ∼80% of the mice (Figure 1), there was severe focal and moderate overall Purkinje cell loss accompanied by astrogliosis in the molecular layer (Figure 2). Purkinje cell bodies varied focally in shape and size, and some were negative for calbindin, a specific Purkinje cell marker. Degeneration progressed over the following months with severe Purkinje cell loss and gliosis in the molecular layer followed by shrinkage of the molecular layer and granule cell loss. At 25 weeks, 3 months after onset of symptoms, the number of Purkinje cell bodies and their dendrites in the molecular layer was dramatically reduced (Figures 2 and 4A) and astrogliosis was evident in both molecular and granule cell layers. At 49 weeks, Purkinje cells had virtually disappeared; the very few remaining Purkinje cells still expressed the (truncated) PrP both in soma and dendrites (Figure 2). Shrinkage of the molecular layer was striking and gliosis was prominent. There was neither Purkinje cell loss nor glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in age-matched Prnpo/o and Prnpo/+ mice (Figure 2), indicating that the age-dependent Purkinje cell loss in the transgenic mice was due to L7-specific expression of truncated PrP, rather than to the absence of PrP. The phenotype of the L7-ΔPrP mice was thus similar to that of the three Nagasaki-type PrP knockout lines exhibiting upregulation of Dpl (Sakaguchi et al., 1996; Moore et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2001). In Zürich II PrP knockout mice, which are of the Nagasaki-type, there was an average Purkinje cell loss of 40% at 30 weeks, and at 40 weeks 50% of the mice were ataxic (Rossi et al., 2001). As in the case of L7-ΔPrP mice, Dpl-induced Purkinje cell loss progressed over several months and exceeded 80% after 63 weeks (Rossi et al., 2001). Purkinje cell loss was also accompanied by cerebellar astrogliosis (Atarashi et al., 2001; Rossi et al., 2001).

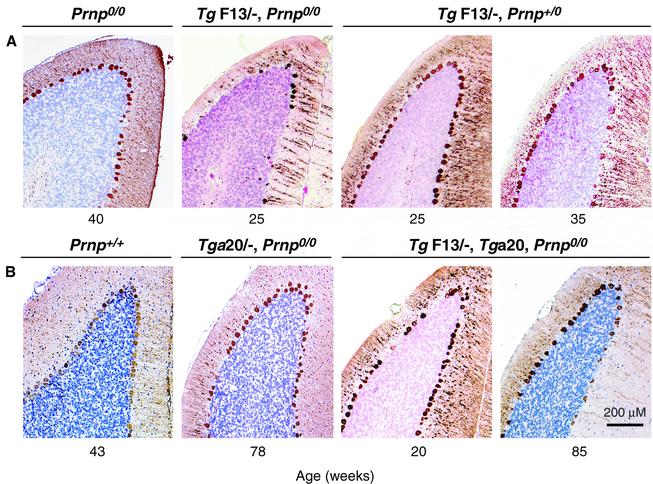

Fig. 4. Purkinje cell degeneration in L7-ΔPrP transgenic mice is mitigated by co-expression of PrP. Cerebellar sections were immunostained for calbindin, a marker for Purkinje cells. Prnpo/o and wild-type (Prnp+/+) controls show normal Purkinje cell layers at 40 and 43 weeks, respectively. (A) L7-ΔPrP mice (TgF13/–,Prnpo/o) at 25 weeks presented with severe loss of Purkinje cell dendrites and cell bodies, associated with a reduction of the molecular layer. In the presence of a wild-type allele (TgF13/–,Prnpo/+), Purkinje cell loss was completely abrogated at 25 weeks and strongly mitigated at 35 weeks. (B) Introduction of the Tga20 transgene cluster into L7-ΔPrP mice (TgF13/–,Tga20/–,Prnpo/o) resulted in PrP expression in brain, except in the Purkinje cells; in these mice, Purkinje cell loss was practically abrogated at 20 weeks and mitigated at 85 weeks of age. There was also a slight Purkinje cell loss in the age-matched controls (Tga20/–,Prnpo/o).

Abrogation of the pathogenic effect of truncated PrP by a Prnp wild-type allele

We next examined whether co-expression of PrP could rescue the phenotype as described for the Nagasaki-type mice (Nishida et al., 1999; Rossi et al., 2001). TgF13 mice (expressing L7-ΔPrP) were crossed with C57BL/6 mice, and the resulting transgenic TgF13/–,Prnpo/+ mice were assessed by their home cage behaviour for 1 year. Intro duction of the wild-type PrP allele did not downregulate the expression of the truncated PrP in the Purkinje cells (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 1, all eight transgenic TgF13/–,Prnpo/+ mice analysed remained healthy for >11 months. Cerebella of transgenic TgF13/–,Prnpo/+ mice were analysed for Purkinje cell loss at 25 weeks, 35 weeks and 1 year of age. No obvious reduction in the number of Purkinje cells (Figure 4A) and no astrogliosis (data not shown) were observed at 25 weeks of age, when severe Purkinje cell loss and reduction of the molecular layer were evident in the absence of a wild-type PrP allele. At 35 weeks, there was a slight to moderate loss of Purkinje cells with a few reactive Bergman glia cells, but no astrogliosis in the molecular layer (data not shown). Cerebella of 1-year-old healthy TgF13/–,Prnpo/+ mice showed moderate Purkinje cell loss that was not found in aged-matched Prnpo/+ mice (data not shown). In contrast, Purkinje cells were completely absent and shrinkage of the molecular layer was evident in 1-year-old ataxic transgenic TgF13/–,Prnpo/o mice. There was a moderate loss of granule cells, possibly due to disappearance of their Purkinje cell targets, which was not found in Prnpo/+ controls (data not shown). Thus, a wild-type PrP allele fully abrogated the clinical manifestations elicited by L7-ΔPrP transgene expression, although it did not completely suppress Purkinje cell loss. Similarly, mice carrying one wild-type PrP and one Zürich II PrP allele showed no clinical symptoms after as long as 100 weeks (Rossi et al., 2001).

Abrogation of the pathogenic effect of truncated PrP by a Tga20 allele cluster expressing PrP in brain with the exception of Purkinje cells

It was suggested earlier that PrP did not have to be expressed in Purkinje cells in order to rescue the Dpl-induced phenotype in Zürich II mice (Rossi et al., 2001) because PrP expressed under the direction of the ‘half-genomic’ PrP promoter (the Tga20 gene cluster) abrogated the clinical phenotype, although this promoter is active in brain in general but not in Purkinje cells (Fischer et al., 1996; Rossi et al., 2001). We bred the Tga20 allele cluster into transgenic TgF13/–,Prnpo/o mice. Of 11 double transgenic mice (TgF13/–,Tga20/–,Prnpo/o) analysed, none developed behavioural abnormalities within 1 year (Figure 1). At 20 weeks, there was complete suppression of Purkinje cell degeneration in the cerebella of those mice (Figure 4B). However, we found moderate Purkinje cell loss in an 85-week-old double-transgenic mouse, as compared with slight Purkinje cell loss, without astrogliosis, in a 78-week-old control mouse hemizygous for the Tga20 allele cluster. We cannot exclude the possibility that levels of PrP undetectable by our immunohistochemical analysis sufficed to ensure Purkinje cell survival. Alternatively, perhaps PrP expressed at the synapses of neighbouring cells can supply the protective effect or can be physically transferred, as shown for PrP in vitro (Liu et al., 2002) and for other GPI-linked proteins in vitro (Anderson et al., 1996) and in vivo (Kooyman et al., 1995). In Purkinje cells of wild-type mice, PrP is found at pre- and postsynaptic spines (Haeberle et al., 2000). In the cerebellum, PrP is also found on other neuronal cells, such as Golgi type II, stellate and basket cells, and to a lesser extent on granule cells (Laine et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2001; Ford et al., 2002).

Discussion

This project aimed to determine whether expression of N-terminally truncated PrP (PrPΔ32–134) targeted specifically to Purkinje cells of Zürich I PrP knockout mice resulted in the same phenotype observed in three lines of Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice with upregulation of Dpl in brain, namely ataxia and Purkinje cell degeneration, which was abrogated by PrP.

Indeed, transgenic mice overexpressing truncated PrP in Purkinje cells under the control of the L7 promoter developed ataxia and Purkinje cell degeneration similar to that of Nagasaki-type mice, but 8 months earlier than the latter (Rossi et al., 2001). Because onset of ataxia in Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice is inversely correlated with the expression levels of Dpl in the brain (Rossi et al., 2001), we assume that the earlier onset of the phenotype in our L7-ΔPrP transgenic lines is due to the high expression level of the truncated PrP. Introduction of a wild-type PrP allele into L7-ΔPrP transgenic Prnpo/o mice rescued the phenotype completely: there was no Purkinje cell loss in L7-ΔPrP transgenic Prnpo/+ at 6 months of age and only a slight reduction of Purkinje cells in mice older than 8 months. Similarly, Purkinje cell degeneration caused by ectopic expression of Dpl in a Nagasaki-type line Zürich II was suppressed in the presence of a wild-type Prnp or Tga20 allele for >20 months, and there was also a mild Purkinje cell loss in older mice expressing the Tga20 allele (Rossi et al., 2001). Moreover, Dpl-induced Purkinje cell loss in Nagasaki-type lines is accompanied by astrogliosis (Sakaguchi et al., 1996; Rossi et al., 2001). Astrogliosis was present in the cerebellum, but also in the white matter of the forebrain. Because there was no evidence of neuronal damage other than Purkinje cell degeneration, the reason for activation of glia and microglia in the forebrain of Nagasaki PrP-null mice remains unclear (Atarashi et al., 2001). In the cerebellum, astrogliosis occurred several months before the onset of Purkinje cell degeneration (Atarashi et al., 2001). Likewise, astrogliosis is already apparent in 3-week-old L7-ΔPrP transgenic Prnpo/o mice, when the Purkinje cell layer appears still normal. Astrogliosis is a prominent histopathological feature in Dpl- and L7-ΔPrP-expressing PrP null mice, which is completely absent in the presence of wild-type PrP. Taken together, the phenotype caused by the L7-controlled overexpression of the truncated PrP (PrPΔ32–134) and its rescue by wild-type PrP strongly suggests that L7-ΔPrP transgenic Prnpo/o mice closely mimic Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice with ectopic expression of Dpl.

The ataxic syndrome is due specifically to overexpression of truncated PrP and not just overexpression of PrP in general, because several fold overexpression of the truncated PrP in Purkinje cells in L7-ΔPrP transgenic mice is completely abrogated by a Prnpo/+ allele contributing an additional amount of PrP. Our findings support the proposal that the truncated PrP and Dpl cause cell death by the same mechanism, perhaps by interfering with a signalling pathway essential for maintenance of cell viability, which is normally activated by PrP, or, in its absence, by a conjectural functional homologue (Shmerling et al., 1998). Alternatively, truncated PrP and Dpl might activate an apoptotic pathway that normally is kept quiescent by PrP (or a functional homologue). It is of interest in this context that stimulation of differentiated neuronal cells by a monoclonal antibody to PrP leads to activation of the tyrosine kinase Fyn, which has been interpreted as pointing to a signalling function for PrP (Mouillet-Richard et al., 2000). The findings that neuronal cultures of Nagasaki-type PrP knockout mice, which presumably express Dpl, undergo apoptosis more readily than wild-type cultures (Kuwahara et al., 1999) and that PrP protects against Bax-mediated apoptosis (Bounhar et al., 2001) suggest an anti-apoptotic role for PrP. However, other or additional functions have been proposed for PrP, such as cell–cell interactions (Rieger et al., 1997), copper transport (Pauly and Harris, 1998; Brown, 1999) and resistance to oxidative stress (Brown et al., 1999; Wong et al., 2000). Wong et al. (2001) proposed that Dpl expression exacerbates oxidative damage that is antagonistic to the protective function of wild-type PrP. A deeper understanding of the normal function of PrP and Dpl is required to elucidate the processes leading to cell death by ectopic expression of Dpl or of truncated PrP lacking the flexible tail of PrP.

Materials and methods

Generation of transgenic mice

The expression vector L7-PrPΔ32–134 encoding PrPΔ32–134 under control of the L7 promoter was generated by blunt end ligation of the KpnI–NarI fragment of plasmid PRP123.F (Shmerling et al., 1998) into the blunted BamHI site of plasmid L7-pGEM3 (Oberdick et al., 1990). The vector was digested with HindIII and EcoRI, purified and injected into fertilized oocytes from Prnpo/o mice as described (Shmerling et al., 1998). Line F13 resulted from injection into fertilized oocytes from Prnp+/+ (F1 of C57BL/6 × DBA/2) mice. Founders were identified by Southern blot analysis of BamHI-digested tail DNA using the PrP open reading frame probe and mated to Prnpo/o Zürich I mice (Büeler et al., 1992) to establish transgenic lines with a Prnpo/o background.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Animals were culled, and their brains were removed and fixed for at least 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fixed samples were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 1–2 µm and processed for haematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining, GFAP, calbindin or PrP immunostaining, as described (Rossi et al., 2001). Briefly, GFAP immunostaining was performed by using anti-GFAP rabbit antiserum (1:300; Dako Glostrup, Denmark). For staining of Purkinje cells, sections were stained with anti-calbindin monoclonal antibody (1:5000; Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MO), and visualized by a biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse antibody (1:200; Dako) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. PrP was detected on microwave-treated sections using polyclonal anti-rabbit antibody R340 (1:200), and visualization was performed with the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) kit (NEN™; Life Science, Boston, MA) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Behavioural assessment

Mice were analysed at 2-week intervals for behavioural abnormalities, such as reduced exploratory activities, trembling gait and ataxia. Footprints of mice were performed as described (Rossi et al., 2001).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank James Morgan for the kind gift of plasmid L7-pGEM, and Marijana Stagliar and Susanne Mirold for the excellent assistance with animal work. This study was supported by the Canton of Zürich, by grants from the Schweizerische Nationalfonds to A.A. and C.W. and from the Medical Research Council to John Collinge and C.W.

References

- Anderson S.M., Yu,G., Giattina,M. and Miller,J.L. (1996) Intercellular transfer of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked protein: release and uptake of CD4-GPI from recombinant adeno-associated virus-transduced HeLa cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 5894–5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atarashi R., Sakaguchi,S., Shigematsu,K., Arima,K., Okimura,N., Yamaguchi,N., Li,A., Kopacek,J. and Katamine,S. (2001) Abnormal activation of glial cells in the brains of prion protein-deficient mice ectopically expressing prion protein-like protein, PrPLP/Dpl. Mol. Med., 7, 803–809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler K., Oesch,B., Scott,M., Westaway,D., Wälchli,M., Groth,D.F., McKinley,M.P., Prusiner,S.B. and Weissmann,C. (1986) Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell, 46, 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A., Brandner,S., Genoud,N. and Aguzzi,A. (2001) Normal neurogenesis and scrapie pathogenesis in neural grafts lacking the prion protein homologue Doppel. EMBO Rep., 2, 347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A., Genoud,N., Naumann,H., Rulicke,T., Janett,F., Heppner, F.L., Ledermann,B. and Aguzzi,A. (2002) Absence of the prion protein homologue Doppel causes male sterility. EMBO J., 21, 3652–3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounhar Y., Zhang,Y., Goodyer,C.G. and LeBlanc,A. (2001) Prion protein protects human neurons against Bax-mediated apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 39145–39149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.R. (1999) Prion protein expression aids cellular uptake and veratridine-induced release of copper. J. Neurosci. Res., 58, 717–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.R., Wong,B.S., Hafiz,F., Clive,C., Haswell,S.J. and Jones,I.M. (1999) Normal prion protein has an activity like that of superoxide dismutase. Biochem. J., 344, 1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büeler H.R., Fischer,M., Lang,Y., Bluethmann,H., Lipp,H.P., DeArmond,S.J., Prusiner,S.B., Aguet,M. and Weissmann,C. (1992) Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature, 356, 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büeler H., Aguzzi,A., Sailer,A., Greiner,R.A., Autenried,P., Aguet,M. and Weissmann,C. (1993) Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell, 73, 1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa R., Piccardo,P., Ghetti,B. and Harris,D.A. (1998) Neurological illness in transgenic mice expressing a prion protein with an insertional mutation. Neuron, 21, 1339–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colling S.B., Collinge,J. and Jefferys,J.G. (1996) Hippocampal slices from prion protein null mice: disrupted Ca2+-activated K+ currents. Neurosci. Lett., 209, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge J., Whittington,M.A., Sidle,K.C., Smith,C.J., Palmer,M.S., Clarke,A.R. and Jefferys,J.G. (1994) Prion protein is necessary for normal synaptic function. Nature, 370, 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donne D.G., Viles,J.H., Groth,D., Mehlhorn,I., James,T.L., Cohen,F.E., Prusiner,S.B., Wright,P.E. and Dyson,H.J. (1997) Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein PrP(29–231): the N terminus is highly flexible. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 13452–13457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M., Rülicke,T., Raeber,A., Sailer,A., Moser,M., Oesch,B., Brandner,S., Aguzzi,A. and Weissmann,C. (1996) Prion protein (PrP) with amino-proximal deletions restoring susceptibility of PrP knockout mice to scrapie. EMBO J., 15, 1255–1264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M.J., Burton,L.J., Li,H., Graham,C.H., Frobert,Y., Grassi,J., Hall,S.M. and Morris,R.J. (2002) A marked disparity between the expression of prion protein and its message by neurones of the CNS. Neuroscience, 111, 533–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeberle A.M., Ribaut-Barassin,C., Bombarde,G., Mariani,J., Hunsmann,G., Grassi,J. and Bailly,Y. (2000) Synaptic prion protein immuno-reactivity in the rodent cerebellum. Microsc. Res. Tech., 50, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herms J.W., Tings,T., Dunker,S. and Kretzschmar,H.A. (2001) Prion protein affects Ca2+-activated K+ currents in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neurobiol. Dis., 8, 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooyman D.L. et al. (1995) In vivo transfer of GPI-linked complement restriction factors from erythrocytes to the endothelium. Science, 269, 89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara C. et al. (1999) Prions prevent neuronal cell-line death. Nature, 400, 225–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine J., Marc,M.E., Sy,M.S. and Axelrad,H. (2001) Cellular and subcellular morphological localization of normal prion protein in rodent cerebellum. Eur. J. Neurosci., 14, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Sakaguchi,S., Atarashi,R., Roy,B.C., Nakaoke,R., Arima,K., Okimura,N., Kopacek,J. and Shigematsu,K. (2000a) Identification of a novel gene encoding a PrP-like protein expressed as chimeric transcripts fused to PrP exon 1/2 in ataxic mouse line with a disrupted PrP gene. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol., 20, 553–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. et al. (2000b) Physiological expression of the gene for PrP-like protein, PrPLP/Dpl, by brain endothelial cells and its ectopic expression in neurons of PrP-deficient mice ataxic due to Purkinje cell degeneration. Am. J. Pathol., 157, 1447–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Zwingman,T., Li,R., Pan,T., Wong,B.S., Petersen,R.B., Gambetti,P., Herrup,K. and Sy,M.S. (2001) Differential expression of cellular prion protein in mouse brain as detected with multiple anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies. Brain Res., 896, 118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Li,R., Pan,T., Liu,D., Petersen,R.B., Wong,B.S., Gambetti,P. and Sy,M.S. (2002) Intercellular transfer of the cellular prion protein. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 47671–47678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K., Wang,W., Xie,Z., Wong,B.S., Li,R., Petersen,R.B., Sy,M.S. and Chen,S.G. (2000) Expression and structural characterization of the recombinant human doppel protein. Biochemistry, 39, 13575–13583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson J.C., Clarke,A.R., McBride,P.A., McConnell,I. and Hope,J. (1994a) PrP gene dosage determines the timing but not the final intensity or distribution of lesions in scrapie pathology. Neurodegeneration, 3, 331–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson J.C., Clarke,A.R., Hooper,M.L., Aitchison,L., McConnell,I. and Hope,J. (1994b) 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol. Neurobiol., 8, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo H., Moore,R.C., Cohen,F.E., Westaway,D., Prusiner,S.B., Wright,P.E. and Dyson,H.J. (2001) Two different neurodegenerative diseases caused by proteins with similar structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 2352–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R.C. et al. (1999) Ataxia in prion protein (PrP)-deficient mice is associated with upregulation of the novel PrP-like protein doppel. J. Mol. Biol., 292, 797–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R.C. et al. (2001) Doppel-induced cerebellar degeneration in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 15288–15293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillet-Richard S., Ermonval,M., Chebassier,C., Laplanche,J.L., Lehmann,S., Launay,J.M. and Kellermann,O. (2000) Signal transduction through prion protein. Science, 289, 1925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida N. et al. (1999) A mouse prion protein transgene rescues mice deficient for the prion protein gene from Purkinje cell degeneration and demyelination. Lab. Invest., 79, 689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdick J., Smeyne,R.J., Mann,J.R., Zackson,S. and Morgan,J.I. (1990) A promoter that drives transgene expression in cerebellar Purkinje and retinal bipolar neurons. Science, 248, 223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauly P.C. and Harris,D.A. (1998) Copper stimulates endocytosis of the prion protein. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 33107–33110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S.B. (1996) Molecular biology and genetics of prion diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 61, 473–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner S.B., Scott,M.R., DeArmond,S.J. and Cohen,F.E. (1998) Prion protein biology. Cell, 93, 337–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger R., Edenhofer,F., Lasmézas,C.I. and Weiss,S. (1997) The human 37-kDa laminin receptor precursor interacts with the prion protein in eukaryotic cells. Nat. Med., 3, 1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riek R., Hornemann,S., Wider,G., Billeter,M., Glockshuber,R. and Wüthrich,K. (1996) NMR structure of the mouse prion protein domain PrP(121–321). Nature, 382, 180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riek R., Hornemann,S., Wider,G., Glockshuber,R. and Wüthrich,K. (1997) NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein, mPrP(23–231). FEBS Lett., 413, 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D., Cozzio,A., Flechsig,E., Klein,M.A., Rülicke,T., Aguzzi,A. and Weissmann,C. (2001) Onset of ataxia and Purkinje cell loss in PrP null mice inversely correlated with Dpl level in brain. EMBO J., 20, 694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer A., Büeler,H., Fischer,M., Aguzzi,A. and Weissmann,C. (1994) No propagation of prions in mice devoid of PrP. Cell, 77, 967–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S. et al. (1995) Accumulation of proteinase K-resistant prion protein (PrP) is restricted by the expression level of normal PrP in mice inoculated with a mouse-adapted strain of the Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease agent. J. Virol., 69, 7586–7592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S. et al. (1996) Loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells in aged mice homozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Nature, 380, 528–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales N., Rodolfo,K., Hassig,R., Faucheux,B., Di Giamberardino,L. and Moya,K.L. (1998) Cellular prion protein localization in rodent and primate brain. Eur. J. Neurosci., 10, 2464–2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmerling D. et al. (1998) Expression of amino-terminally truncated PrP in the mouse leading to ataxia and specific cerebellar lesions. Cell, 93, 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman G.L., Qin,K., Moore,R.C., Yang,Y., Mastrangelo,P., Tremblay,P., Prusiner,S.B., Cohen,F.E. and Westaway,D. (2000) Doppel is an N-glycosylated, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein. Expression in testis and ectopic production in the brains of Prnp(0/0) mice predisposed to Purkinje cell loss. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 26834–26841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler I. et al. (1996) Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature, 380, 639–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuzi N.L., Gall,E., Melton,D. and Manson,J.C. (2002) Expression of doppel in the CNS of mice does not modulate transmissible spongiform encephalopathy disease. J. Gen. Virol., 83, 705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissmann C. (1996) PrP effects clarified. Curr. Biol., 6, 1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissmann C. (1999) Molecular genetics of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissmann C. and Aguzzi,A. (1999) PrP’s double causes trouble. Science, 286, 914–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissmann C., Fischer,M., Raeber,A., Büeler,H., Sailer,A., Shmerling,D., Rülicke,T., Brandner,S. and Aguzzi,A. (1996) The role of PrP in pathogenesis of experimental scrapie. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 61, 511–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B.S., Pan,T., Liu,T., Li,R., Petersen,R.B., Jones,I.M., Gambetti,P., Brown,D.R. and Sy,M.S. (2000) Prion disease: a loss of antioxidant function? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 275, 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B.S. et al. (2001) Induction of HO-1 and NOS in doppel-expressing mice devoid of PrP: implications for doppel function. Mol. Cell. Neurosci., 17, 768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]