Abstract

Contact of developing sensory organs with the external environment is established via the formation of openings in the skin. During eye development, eyelids first grow, fuse and finally reopen, thus providing access for visual information to the retina. Here, we show that eyelid opening is strongly inhibited in transgenic mice overexpressing the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonist noggin from the keratin 5 (K5) promoter in the epidermis. In wild-type mice, enhanced expression of the kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB mediated by an adenovirus vector also inhibits eyelid opening. Noggin overexpression leads to reduction of apoptosis and retardation of cell differentiation in the eyelid epithelium, which is associated with downregulation of expression of the apoptotic receptors (Fas, p55 kDa TNFR), Id3 protein and keratinocyte differentiation markers (loricrin, involucrin). BMP-4, but not EGF or TGF-α, accelerates opening of the eyelid explants isolated from K5-Noggin transgenic mice when cultured ex vivo. These data suggest that the BMP signaling pathway plays an important role in regulation of genetic programs of eyelid opening and skin remodeling during the final steps of eye morphogenesis.

Keywords: Fas/involucrin/loricrin/p55TNFR/skin

Introduction

Skin morphogenesis is a complex process resulting not only in an organ that covers and protects the body (Fuchs and Raghavan, 2002), but also in the formation of openings overlying sensory organs, such as the eye or ear, to provide access for environmental signals to sensory epithelia. During eye development, the skin forms eyelids, which first grow and fuse, thus covering corneal epithelium, and then reopen at a certain developmental stage when the eye becomes morphologically and functionally mature to accept visual signals (Findlater et al., 1993). The process of eyelid opening requires a high degree of coordination between cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation (Teraishi and Yoshioka, 2001). While signaling through epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) accelerates eyelid opening (Cohen, 1962; Smith et al., 1985; Tam, 1985), other signaling pathways that control this process remain poorly understood.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) play pivotal roles in the control of morphogenesis of the skin, as well as in eye development: BMP-4 induces epidermal cell fate in the early embryo, and later together with BMP-7 regulates lens formation and ciliary body development (Hogan, 1996, 1999; Zhao et al., 2002). BMPs also regulate morphogenesis of skin appendages (Blessing et al., 1993; Noramly and Morgan, 1998; Botchkarev et al., 1999; Kulessa et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2002). Noggin is a secreted protein that modulates the activity of BMP-2/4/7 and growth differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) in vivo by preventing their interaction with BMP receptors (Zimmerman et al., 1996; Miyazono et al., 2001; Groppe et al., 2002). This modulation is critically important for proper orchestration of a large variety of developmental events (Hogan, 1999; Massagué and Chen, 2000). Indeed, noggin knockout mice show multiple defects in skeletal and nervous system development, leading to their lethality shortly prior to birth (Brunet et al., 1998; McMahon et al., 1998).

BMPs exert their biological effects by binding to specific BMP receptor complexes, which transduce the signal to the nucleus via the BMP-Smad and BMP-MAP kinase pathways (von Bubnoff and Cho, 2001). Both pathways are implicated in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis during embryonic development (reviewed in Hogan, 1996, 1999). Using a transgenic mouse approach, it was shown that BMP-4 and noggin also play important roles in the regulation of cell differentiation and apoptosis during postnatal development (Blessing et al., 1993; Kulessa et al., 2000; Guha et al., 2002). However, the in vivo functions of noggin in the regulation of eyelid opening remain unclear.

Here, we show that transgenic (TG) mice overexpressing BMP-antagonist noggin under the control of the keratin 5 (K5) promoter display severe inhibition of eyelid opening accompanied by alterations of both apoptosis and cell differentiation in the eyelid epithelium. We also show that in wild-type (WT) mice, enhanced expression of a kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB mediated by an adenovirus vector inhibits eyelid opening. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the inhibition of eyelid opening seen in K5-Noggin mice is associated with downregulation of the apoptotic receptors (Fas, p55 kD TNFR), Id3 protein and keratinocyte (KC) differentiation markers (loricrin, involucrin) in the eyelid epithelium. Finally, we show in ex vivo experiments that BMP-Smad and EGFR signaling operate as two parallel pathways in regulating eyelid opening, suggesting important roles for BMPs and noggin in controlling skin remodeling during the final steps of eye morphogenesis.

Results

Noggin-overexpressing mice show severe retardation of eyelid opening

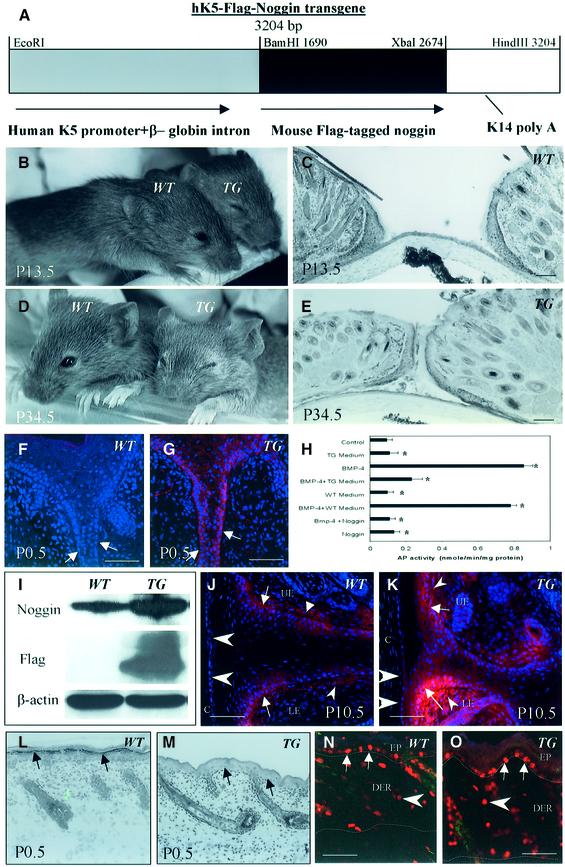

To explore the roles of BMP-2/4/7 and GDF-5 and their antagonist noggin in the regulation of skin remodeling during eyelid opening, TG mice expressing noggin in the basal epidermal KCs under the control of the K5 promoter were generated (Figure 1). The noggin cDNA containing a 5′ flag epitope was inserted into a targeting vector containing the human K5 promoter (Figure 1A). Two TG founder lines were generated using C3H/HeJ mice as a background strain. Both lines of TG mice were viable, fertile and showed a weight similar to WT mice at postnatal day 0.5 (P0.5), while showing significantly (P < 0.05) retarded weight gain thereafter (15.3 ± 1.7 g versus 19.7 ± 2.1 g seen in WT mice at P30.5).

Fig. 1. Creation of transgenic mice overexpressing noggin in the epidermis. (A) Scheme of the transgene construct. (B and D) Inhibition of eyelid opening observed in transgenic (TG) mice at P13.5 and P34.5. (C and E) Microscopy of eyelids in WT and TG mice. (F and G) Expression of Flag in the EJE of TG mice (G, arrows) using antiserum against Flag protein. Lack of expression in WT mice (F). (H) Alkaline phosphatase activity in murine osteoblasts induced by BMP-4 after incubation with media isolated from cultured TG or WT keratinocytes (KCs), or with purified noggin protein. (I) Western blot analysis of 64 kDa noggin protein detected by antisera to full-length mouse noggin or to the Flag protein tagged to the uncleaved noggin in lysates of WT and TG eyelid skin at P0.5. (J and K) Immunofluorescence with antiserum against noggin shows expression in the EJE, the dermis and the corneal epithelium of TG mice (K, arrows, small and large arrowheads, respectively), and in WT mice (J) at P10.5. (L and M) Histological images of dorsal skin of newborn WT and TG mice. Lack of granular layer in the TG epidermis (M, arrows), compared with the WT epidermis (L, arrows). (N and O) Immuno-visualization of Ki67 (red fluorescence) and TUNEL (green fluorescence) in dorsal skin of WT and TG at P7.5. Proliferating cells in the epidermis and dermis are indicated by arrows and arrowheads, respectively. Epidermal/dermal and dermal/subcutaneous borders are indicated by dotted lines. C, cornea; LE and UE, lower and upper eyelids, respectively. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Both lines of TG mice had markedly delayed eyelid opening. While in WT mice, eyelids were open by P13.5, K5-Noggin mice showed a delay in eyelid opening of 17–24 days (average 20.5 days; Figure 1B–E). The process of eyelid opening was equally retarded in both male and female TG mice. No visible abnormalities in corneal development were seen in K5-Noggin mice (Figure 1C and E). In contrast to eyelid development, K5-Noggin mice showed no macroscopic abnormalities in external auditory canal formation or limb development compared with WT mice. Abnormalities in hair follicle development and cycling observed in TG mice will be described elsewhere.

Transgene expression was monitored by immunofluorescent Flag visualization. K5-Noggin mice showed strong transgene expression in the epidermal basal layer of the eyelid junction, while no specific signal was seen in WT skin (Figure 1F and G). To identify whether transgene-derived noggin protein is able to neutralize BMP activity, we tested the capacity of the medium derived from cultured transgenic KCs (or from WT KCs as a control) to neutralize BMP-4-induced osteoblast differentiation. Osteoblast differentiation was monitored by analyzing alkaline phosphatase activity (Aoki et al., 2001). Our data suggest that the medium derived from TG KCs significantly (P < 0.05) reduced alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblasts induced by BMP-4, similar to that seen after the addition of purified noggin protein to osteoblasts incubated with BMP-4 (Figure 1H). In contrast, the medium derived from WT KCs failed to significantly reduce alkaline phosphatase activity induced by BMP-4 in these cells. These data suggest that the transgene-derived noggin retains BMP-inhibitory activity similar to WT noggin protein.

To determine whether TG mice show an increase of noggin protein in skin, western blot analysis and immunofluorescent stainings were preformed. By western blotting, high levels of 64 kDa noggin protein, determined using anti-noggin or anti-flag antisera, were detected in the eyelid skin of TG mice (Figure 1I). In contrast to TG skin, the lower levels of noggin expression or lack of any signal were detected in WT skin lysates after using the anti-noggin and anti-flag antisera, respectively (Figure 1I). Compared with WT mice (Figure 1J), noggin expression was increased in the eyelid junction epithelium (EJE) and in the dermis of TG mice (Figure 1K).

Newborn TG mice showed a lack of the granular layer in the epidermis (Figure 1L and M). However, a clear granular layer was visible in TG mice by 7–8 days. At P7.5, when the major morphogenetic steps in skin development are already complete, TG mice showed a significantly (P < 0.01) increased thickness of the epidermis (42.4 ± 5.6 µm) and dermis (171.8 ± 19.5 µm) compared with the corresponding parameters of WT mice (24.9 ± 6.5 and 103.8 ± 17.3 µm, respectively). These changes, however, were not accompanied by significant alterations in epidermal proliferation or apoptosis compared with WT skin (Figure 1N and O).

All key components of the BMP signaling pathway (noggin, BMP-2/4/7, GDF-5, BMP receptors, Smad1/5 proteins) are expressed in developing eyelid epithelium

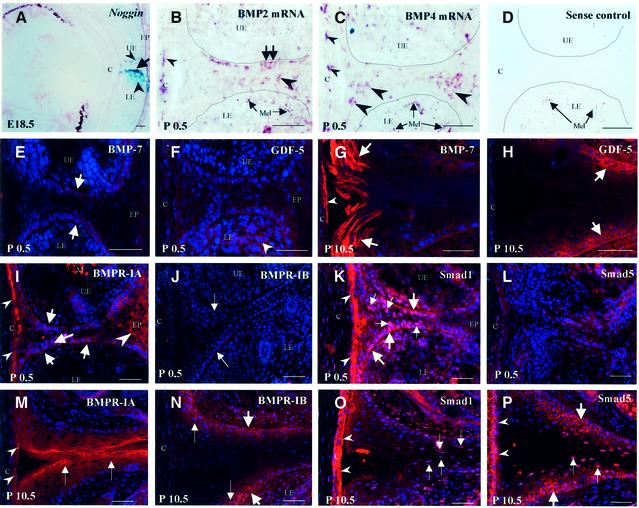

To investigate the role of BMP signaling in skin remodeling during eyelid opening, we examined the expression patterns of noggin, BMP-2/4/7, GDF-5, BMP receptors and Smad1/5 in murine eyelid skin between embryonic day 18.5 (E18.5) and P13.5; times when eyelids are fully closed and open, respectively (Findlater et al., 1993). At E18.5, noggin knockout (+/) mice with a lacZ gene targeted to the noggin locus (McMahon et al., 1998) showed strong expression of noggin in both the epithelium and mesenchyme of the lower eyelid, while relatively weak expression was observed in the mesenchyme of the upper eyelid (Figure 2A). In WT mice, BMP-2 and BMP-4 mRNAs were detected in single cells of the EJE, cornea and dermis at P0.5 (Figure 2B and C), and later at P7.5–P10.5 (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Expression patterns for noggin, BMP-2 and BMP-4 mRNAs, BMP-7, GDF-5, BMP receptors and Smad1/5 proteins during eyelid opening. Cryo-sections of E18.5 murine embryos and P0.5–P10.5 postnatal mice were processed for microscopic visualization of noggin, BMP-2/4 mRNAs, BMP-7, GDF-5, BMPR-IA/IB and Smad1/5. (A) Noggin. LacZ activity in the epithelium of the lower eyelid (arrow) and in the mesenchyme of the upper and lower eyelids (arrowheads) of noggin knockout (+/–) mice. (B–D) BMP-2/4 mRNAs. In situ hybridization signals in basal and suprabasal cells of the eyelid junction (arrows and large arrowheads, respectively), and in corneocytes (small arrowheads) at P0.5. Sense control for BMP-4 mRNA is shown in (D). Melanin granules in (C) and (D) are shown by arrows. (E and G) BMP-7. Expression in basal (E, arrows) and differentiating cells (G, arrows) of the EJE at P0.5 (E) and P10.5 (G). (F and H) GDF-5. Expression in the eyelid mesenchyme (arrowheads) and in basal cells of the EJE (arrows) at P0.5 (F) and P10.5 (H). (I and M) BMPR-IA. Expression in basal and differentiating cells of the EJE, and in corneocytes (arrows, large and small arrowheads, respectively) at P0.5 (I) and P10.5 (M). (J and N) BMPR-IB. Lack of expression in the eyelids at P0.5 (J, arrows). Expression in basal and suprabasal cells of the EJE at P10.5 (N, large and small arrows, respectively). (K and O) Smad1. Nuclear expression in basal and suprabasal cells of the EJE and in corneocytes (large and small arrows and arrowheads, respectively) at P0.5 (K) and P10.5 (O). (L and P) Smad5. Lack of nuclear expression in the eyelids at P0.5 (L). Expression in the basal and suprabasal cells of the EJE and in corneocytes at P10.5 (P, large and small arrows and arrowheads, respectively). C, cornea; LE and UE, lower and upper eyelids, respectively; Mel, melanin. In (B–D), a border between the EJE and the dermis is indicated by dotted line. Scale bars: 50 µm.

Only faint expression of BMP-7 and GDF-5 proteins was observed in eyelids at P0.5 (Figure 2E and F), while at P10.5 an increase of BMP-7 and GDF-5 immunoreactivity was found in the differentiating and basal cells of the EJE, respectively (Figure 2G and H). Both BMPR-IA and Smad1 proteins were expressed in the EJE and cornea of newborn mice (Figure 2I and K), while no BMPR-IB expression was observed at this time (Figure 2J). At P0.5, strong cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of Smad1 was found in basal and suprabasal cells of the EJE (Figure 2K), while only weak cytoplasmic Smad5 expression was seen in the EJE (Figure 2L). At P10.5, BMPR-IA and Smad1 proteins were expressed in differentiating cells of the EJE (Figure 2M and O), while BMPR-IB and Smad-5 were seen in both basal and suprabasal KCs (Figure 2N and P). Most importantly, both Smad-1 and Smad-5 showed nuclear patterns of expression in suprabasal cells of the EJE at P10.5 (Figure 2O and P), suggesting their involvement in the regulation of cell differentiation.

Noggin transgenic mice show reduced apoptosis in developing eyelid epithelium

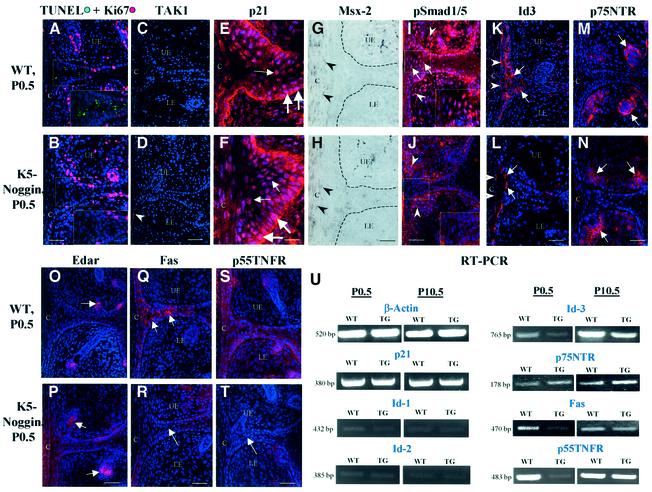

To analyze the mechanisms that are involved in the control of eyelid opening by BMPs and noggin, we first compared the dynamics of cell proliferation and apoptosis in the eyelid epithelium between WT and TG mice. No significant difference (P > 0.05) between the number of Ki-67+ cells in the EJE was found between WT and TG mice at P0.5 (Figure 3A and B), or at later times (P7.5–P13.5; data not shown). In WT mice, maximal apoptosis detected by TUNEL was observed in the triangle between the inner epithelial portions of the upper and lower eyelids and cornea at P0.5 (Figure 3A). However, newborn TG mice showed a significant reduction in the number of TUNEL+ cells in this area of the eyelid epithelium, compared with WT mice (4.7 ± 0.6 per microscope field versus 13.5 ± 2.4 per microscope field in WT mice, P < 0.01; Figure 3B). In WT mice, TUNEL+ cells became visible in the EJE at P1.5 and quickly disappeared from this area by P2.5, while TUNEL+ cells were still visible in the EJE of TG mice up to P7.5 (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Alterations in expression of the apoptotic markers in K5-Noggin mice. Eyelid skin was isolated from newborn WT or transgenic (TG) mice and processed for immunofluorescence (A–F, I–T), in situ hybridization (G, H) or semi-quantitative RT–PCR (U) protocols for analyses of the expression of apoptotic markers. (A and B) TUNEL (green) plus Ki67 (red). Marked decrease of TUNEL+ cells in TG mice (B, labeled area) compared with WT mice (A, labeled area). (C and D) TAK1. Lack of expression in the EJE of both WT and TG mice. (E and F) p21. Strong expression in basal and suprabasal eyelid keratinocytes (KCs) (large and small arrows, respectively). (G and H) Msx-2. Lack of in situ hybridization signal in the EJE and weak expression in the corneal epithelium (arrowheads). The border between eyelid epithelium and mesenchyme is indicated by the dotted lines. (I and J) pSmad1/5. Decrease of nuclear pSmad1/5 expression in the EJE (J, labeled area) and mesenchyme (J, arrowheads) of TG mice compared with the same structures in WT mice (I). (K and L) Id3. Decrease of expression in the EJE of TG mice (L, arrows) compared with WT mice (K). (M and N) p75NTR. Expression in mesenchyme around developing hair follicles (arrows). (O and P) Edar. Expression in the epithelium of developing hair follicles (arrows). (Q and T) Fas and p55TNFR. Marked decrease of expression in the eyelids of TG mice (R, T, arrows), compared with WT mice (Q, S, arrows). (U) Semi-quantitative RT–PCR. Eyelid skin dissected from WT and K5-Noggin TG mice was processed for semi- quantitative RT–PCR of β-actin, p21, Id1, Id2, Id3, p75NTR, Fas and p55TNFR. Representative gels from one of three experiments each are shown. C, cornea; LE and UE, lower and upper eyelids, respectively. Scale bars: (A–D) and (I–T), 50 µm; (E–F), 25 µm.

Next, the expression patterns for markers implicated in BMP-mediated apoptosis (XIAP, TAK1 kinase, Msx-2 transcription factor and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21; von Bubnoff and Cho, 2001) were compared between eyelids of WT and TG mice. However, no expression of TAK1 kinase (Figure 3C and D) and XIAP (data not shown) was detected in the EJE of either WT or TG mice at P0.5–P10.5. The p21 protein showed similar expression patterns in nuclei of differentiating cells of WT and TG mice (Figure 3E and F). No differences in the expression levels of p21 transcripts were found between WT and TG skin at P0.5 or P10.5 (Figure 3U). No expression of Msx-2 mRNA was seen in the EJE of WT and TG mice at P0.5 (Figure 3G and H) or P7.5 (data not shown). These data suggest that XIAP, TAK1, p21 and Msx-2 most likely do not contribute to the alterations of apoptosis observed in the eyelid epithelium of TG mice.

Inhibition of apoptosis in K5-Noggin mice is associated with downregulation of pSmad1/5, Id3 protein and apoptotic receptors (Fas, p55TNFR) in the eyelid epithelium

The BMP-Smad pathway has also been implicated in apoptosis regulation by controlling the expression of BMP target genes (von Bubnoff and Cho, 2001). In newborn WT mice, strong nuclear expression of pSmad1/5 was found in cells located in the triangle between the inner epithelial portions of the upper and lower eyelids and cornea (Figure 3I), i.e. in the area where maximal apoptosis was seen (Figure 3A). However, in newborn TG mice, only weak cytoplasmic pSmad1/5 expression was detected in cells of this area and in other cells of the EJE (Figure 3J). This suggests that Smad1/5 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation are both decreased in TG mice, which implicates Smad involvement in mediating BMP-induced apoptosis during eyelid opening.

Id proteins (inhibitors of DNA binding/differentiation) and the p75 kD neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) are important targets for BMP regulation and are also capable of inducing apoptosis (Botchkarev et al., 1999; Yokota, 2001). To examine the possible involvement of Id proteins and ‘death-domain’ receptors in BMP-mediated apoptosis during eyelid opening, the expression of Id1/2/3, p75NTR, p55 kD TNF receptor (p55TNFR), Fas and the ectodermal dysplasia receptor (Edar) in the eyelid epithelium was compared between WT and TG mice at P0.5–P10.5. Among different members of the Id family, only the Id3 protein and its transcripts were expressed in the developing eyelid epithelium of newborn WT mice (Figure 3K and U). Only weak expression of Id1/2 transcripts was seen in both WT and TG eyelid skin at P0.5 (Figure 3U), while no Id1/Id2 protein expression was evident by immunofluorescence (data not shown). In contrast to WT mice, Id3 protein and mRNA expression were markedly decreased in eyelids of TG mice at P0.5–P10.5 (Figure 3L and U). p75NTR and Edar expression was not significantly different between WT and TG mice (Figure 3M–P), but the expression of the Fas and p55TNFR proteins and their mRNAs was strongly reduced in the eyelids of newborn TG mice compared with WT mice (Figure 3Q–T and U). In contrast to WT mice, the onset of expression of both Fas and p55TNFR proteins in the EJE of TG mice was delayed by 7–9 days, and at P10.5 lower levels of both Fas and p55TNFR transcripts were present in the eyelids of TG mice, compared with WT animals (Figure 3U). These data suggest that BMPs may promote apoptosis in the developing eyelid epithelium by regulating the expression of Id3, Fas and p55TNFR.

K5-Noggin mice show alterations in keratinocyte differentiation during eyelid epithelium development

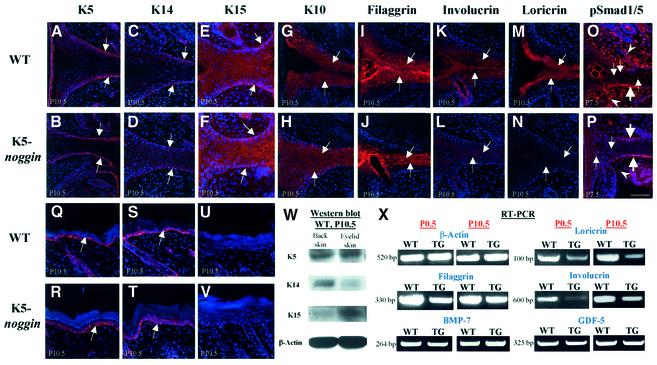

To examine whether the inhibition of eyelid opening seen in TG mice may also be due to the alterations in cell differentiation, the dynamics of epidermal keratins and KC differentiation markers in eyelids were compared between WT mice and TG mice at P0.5–P10.5. Abundant amounts of K5 were present in basal epidermal KCs of back skin and eyelid skin in both WT and TG mice (Figure 4A, B, Q and R). However, the level of K14 was significantly decreased in the eyelids of both WT and TG mice compared with back skin (Figure 4C, D, S and T). Instead, K15 was present in basal and suprabasal KCs of eyelid skin in WT and TG mice, while it was lacking in the epidermis of back skin (Figure 4E, F, U and V). This result was confirmed by western blot analysis, which showed a marked decrease of K14 protein and an increase of K15 in the lysates of eyelid skin compared with back skin (Figure 4W).

Fig. 4. Differences in the expression of keratinocyte differentiation markers in eyelid epithelium between WT and K5-Noggin mice. Eyelid and back skin was isolated from WT or TG mice at P7.5–P10.5 and processed for analyses of the expression of keratinocyte (KC) markers, BMP-7, GDF-5 and pSmad1/5 using immunofluorescence (A–V), western blot analysis (W) or semi-quantitative RT–PCR (X). (A and B) and (Q and R): keratin 5. Expression in basal KCs (arrows) of the EJE (A and B) and in back skin (Q and R). (C and D) and (S and T): keratin 14. Decrease of expression (arrows) in the EJE (C and D) compared with back skin (S and T). (E and F) and (U and V): keratin 15. Marked increase of expression (arrows) in the EJE (E and F) compared with back skin (U and V). (G–J) Keratin 10 (G and H) and filaggrin (I and J). Expression in suprabasal KCs of the EJE (arrows). (K–N) Involucrin (K and L) and loricrin (M and N). Marked decrease of expression in the EJE of TG mice compared with WT mice (arrows). (O and P) pSmad1/5. Decrease of pSmad1/5 expression in the basal and suprabasal KCs and in eyelid mesenchyme (P, large arrows, small arrows and arrowheads, respectively) of TG mice compared with the same structures of WT mice (O). Scale bars for (A–L) are 50 µm. (W) Western blot analysis of the K5 (60 kDa), K14 (55 kDa) and K15 (49 kDa) proteins in lysates of the WT eyelid and back skin at P10.5. (X) Semi-quantitative RT–PCR. Eyelid skin dissected from WT and TG mice at P0.5 and P10.5 was processed for semi-quantitative RT–PCR with primers specific for β-actin, filaggrin, involucrin, loricirn, BMP-7 and GDF-5. Representative gels from one of three experiments each are shown.

In eyelid skin, no differences in K10 and filaggrin protein levels were evident between WT and TG mice at P10.5 (Figure 4G–J and X), when all differentiation markers examined showed maximal expression. However, the amounts of involucrin and loricrin proteins and their corresponding transcripts were strongly reduced in eyelids of TG mice at P10.5 compared with WT mice (Figure 4K–N and X). No differences in the transcript levels of BMP-7 and GDF-5, which may regulate keratinocyte differentiation in the EJE, were found between WT and TG eyelids at P10.5 (Figure 4X). In contrast to WT mice, a marked decrease of pSmad1/5 expression was evident in the EJE of TG mice at P7.5 (Figure 4O and P). Thus, these data suggest that the reduced amount of K14 is partially replaced and compensated for by K15 in the developing eyelids of both WT and TG mice. Reduced expression of involucrin and loricrin in TG eyelids suggests that they may be targets for BMP-Smad regulation during eyelid development.

Enhanced expression of a kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB mediated by an adenovirus vector inhibits eyelid opening and keratinocyte differentiation in WT mice

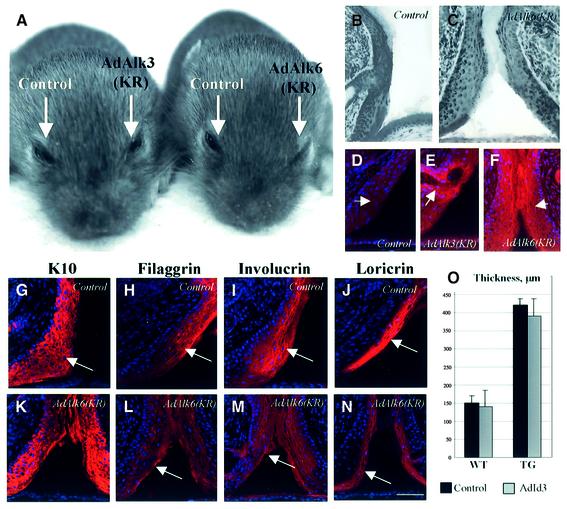

BMP-induced cell differentiation is mediated by both BMPR-IA and BMPR-IB (reviewed in von Bubnoff and Cho, 2001; Botchkarev, 2003). To determine which BMP receptor subtypes are involved in the control of cell differentiation in developing eyelids, adenoviral vectors carrying the kinase-inactive forms of BMPR-IA [AdAlk3(KR)] or BMPR-IB [AdAlk6(KR)] were administered into the conjunctival sac of WT C3H/HeJ mice. The adenoviral vector carrying β-galactosidase was used as a control (Figure 5A–N). As shown previously, adenoviruses carrying the kinase-inactive forms of BMP receptors (AdAlk-3KR and AdAlk-6KR) showed similar expression levels in cultured ATDC5 cells and in medulloblastoma cells (Fujii et al., 1999; K.Funa, unpublished observations). Consistent with these data, AdAlk3(KR) and AdAlk6(KR) showed similar expression patterns in the EJE in vivo when monitored by immunohistochemical detection of kinase-tagged hemagglutinin (Figure 5D–F).

Fig. 5. Administration of an adenoviral vector carrying the kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB inhibits eyelid opening and keratinocyte differentiation in WT mice. Adenoviral vectors carrying kinase-inactive forms of BMPR-IA [AdAlk3(KR)], BMPR-IB [AdAlk6(KR)], Id3 cDNA (AdId3) or β-galactosidase (control) were administered into the conjunctival sac of WT C3H/HeJ mice or K5-Noggin mice at P1.5, P3.5 and P5.5. Eyelid skin was harvested at P13.5 and processed for hematoxylin staining (B, C and O), or immunohistological detection of hemagglutinin, K10, filaggrin, involucrin and loricrin (D–N). (A) Inhibition of eyelid opening after administration of AdAlk6(KR). (B and C) Histological images of eyes treated with control vector (B) or AdAlk6(KR) (C). (D–F) Hemagglutinin immunoreactivity in the EJE (arrows) after AdAlk3KR or AdAlk6(KR) treatment (E and F, respectively). Lack of hemagglutinin expression in the EJE (arrow) after treatment with control vector (D). (G and K) K10 expression in eyelids after control and AdAlk6(KR) treatments (arrows). (H–N) Filaggrin (L), involucrin (M) and loricrin expression (N) after AdAlk6(KR) administration. Corresponding controls are shown in (H), (I) and (J). Scale bars: 50 µm. (O) Width of the eyelid junction in WT and TG mice after treatment with AdId3 (values are means ± SEM).

Administration of AdAlk6(KR) into WT mice was accompanied by inhibition of eyelid opening at P13.5, while mice treated with AdAlk3(KR) or the control vector showed normal eyelid opening (Figure 5A–C). Downregulation of filaggrin, involucrin and loricrin expression was only observed in the EJE after AdAlk-6(KR) treatment (Figure 5L–N) and not in the eyes treated with the control vector (Figure 5H–J) or AdAlk3 (KR) (data not shown). However, no differences in the level of K10 were found between mice treated with either AdAlk6(KR) (Figure 5G and K) or AdAlk3(KR) (data not shown). These data suggest that inhibition of eyelid opening seen in K5-Noggin mice may be reproduced in WT mice by treatment with an adenovirus carrying the kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB.

Among the different markers that were decreased in eyelids of K5-Noggin mice, only Id3 protein is implicated in the control of both apoptosis and differentiation (Yokota, 2001). To test whether inhibition of eyelid opening seen in TG mice could be rescued by enhanced expression of Id3, adenoviruses carrying Id3 (AdId3) or β-galactosidase (control) were injected into the conjunctival sacs of K5-Noggin or WT mice at P1.5, P3.5 and P5.5. In both WT and TG mice, AdId3 administration was only accompanied by a slight acceleration of eyelid opening, which did not differ significantly from the control (Figure 5O). This suggests that regulation of eyelid opening by BMPs is a complex process requiring involvement of several BMP targets, and enhanced expression of only one of them, such as Id3, appears not to be sufficient to rescue the eyelid phenotype seen in K5-Noggin mice.

BMP-4, but not EGF or TGF-α, accelerates opening of K5-Noggin eyelids ex vivo

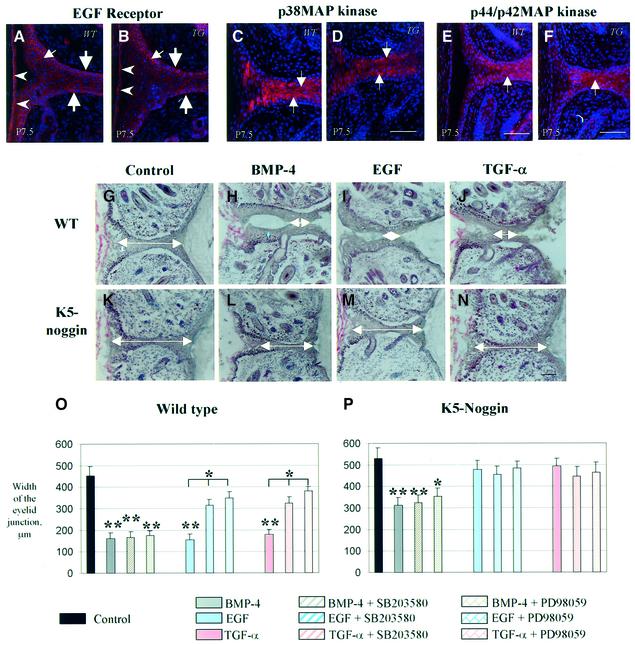

Signaling through the EGFR plays an important role in the regulation of keratinocyte differentiation (Eckert et al., 1997; Fuchs and Raghavan, 2002), and administration of EGFR ligands strongly accelerates eyelid opening in vivo (Cohen, 1962; Smith et al., 1985; Tam, 1985). Cross-talk between EGF and BMP signaling pathways in differentiating osteoblasts has been described previously (Kozawa et al., 2002). To examine whether the retardation of KC differentiation seen in eyelids of TG mice is associated with alterations in EGFR signaling, the expression of EGFR and the components of its signal transduction pathway, p38 and p44/p42 MAP kinases (p38MAPK and p44/p42MAPK), was compared between eyelids of WT and TG mice at P0.5–10.5. However, no differences in the expression of EGFR or the phosphorylated isoforms of p38MAPK and p44/p42MAPK were detected in the eyelids of WT and TG mice at P0.5–P10.5 (Figure 6A–F).

Fig. 6. Effects of BMP-4, EGF and TGF-α on the dynamics of eyelid opening in eyelid skin explants of K5-Noggin and WT mice. Eyelid skin was isolated from WT or transgenic (TG) mice at P7.5 and processed for immunofluorescent detection of EGFR, p38MAPK or p44/p42 MAPK (A–F) or cultured ex vivo in presence of BMP-4, EGF, TGF-α, or their combination with MAPK inhibitors (G–P). (A and B) EGF receptor. Expression in basal and suprabasal cells of the EJE (large and small arrows, respectively) and in corneal epithelium (arrowheads). (C–F) p38MAPK (C and D) and p44/p42MAPK (E and F). Expression in differentiating cells of the EJE (arrows). (G–P) Organ culture. Eyelid skin explants isolated from WT or TG mice at P7.5 were cultured ex vivo for 96 h with mouse normal serum as a control (G and K), BMP-4 (H and L), EGF (I and M), TGF-α (J and N) or with their combinations with p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or p44/p42MAPK inhibitor PD98059. The width of eyelid junction was evaluated and summarized in (O) and (P) (values are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). In (G–N), white arrows indicate the width of the eyelid junction. Scale bars: 50 µm.

To further explore the cross-talk between BMP and EGF signaling pathways in regulating eyelid opening, eyelid skin explants were isolated from P7.5 WT and TG mice. Explants were cultured ex vivo in the presence of BMP-4, EGF, TGF-α or with combinations of either BMP-4, EGF or TGF-α and specific p38MAPK and p44/p42MAPK inhibitors (SB203580 and PD98059, respectively). In WT eyelid explants, BMP-4, EGF and TGF-α significantly accelerated eyelid opening, as indicated by a marked reduction (P < 0.01) in the width of EJE compared with control explants (Figure 6G–J and O). However, in the eyelid explants of TG mice, only BMP-4 significantly (P < 0.05) accelerated eyelid opening, while EGF or TGF-α failed to influence this process significantly (P > 0.1) (Figure 6K–N and P). Furthermore, in WT eyelid explants, the stimulatory activities of EGF or TGF-α on the process of eyelid opening were significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited by administration of p38MAPK or p44/p42MAPK inhibitors (Figure 6O). However, in the explants from both WT and TG mice, administration of MAPK inhibitors did not alter significantly the stimulatory effects of BMP-4 on eyelid opening (Figure 6P). These data suggest that p38 and p42/p42 MAP kinases appear not to be involved in BMP-4-mediated stimulation of eyelid opening, which is most likely regulated via recruitment of the BMPR-Smad signal transduction mechanism.

Discussion

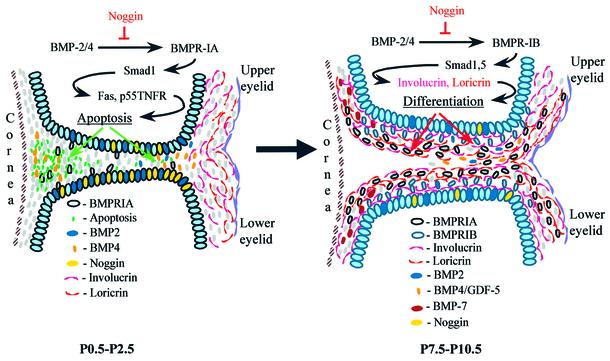

Using a transgenic mouse approach, we show here that the BMP-antagonist noggin functions as an important regulator in controlling eyelid opening and, therefore, in establishing access for environmental signals to the developing eye. We also show that severe retardation of eyelid opening seen in K5-Noggin mice (Figure 1) may be reproduced in WT animals by administration of an adenoviral vector carrying a kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB (Figure 5). This phenotype may be explained by the inhibition of at least two distinct effects of BMPs by noggin in postnatal eyelid skin (Figure 7).

Fig. 7. Model illustrating the involvement of BMPs and noggin in the regulation of eyelid opening. At the beginning of eyelid opening (P0.5–P2.5), BMP-2/4 interact with BMPR-IA and promote apoptosis in EJE via stimulation of the expression of Fas, p55TNFR and Id3 protein. Later (P7.5–P10.5), BMP-2/4/7 and GDF-5, via an interaction with BMPR-IB, regulate keratinocyte differentiation and expression of involucrin and loricrin in the eyelid epithelium. Both BMP-mediated apoptosis and cellular differentiation are significantly modulated by noggin, which is expressed in the eyelid epithelium and regulates the amount of biologically active BMPs available for binding to BMP receptors during eyelid opening.

As eyelid opening begins, we propose that excess noggin inhibits BMP-mediated apoptosis in the epithelium of the eyelid junction. Most likely, noggin prevents BMP-2/4 interaction with BMPR-IA expressed in the eyelid epithelium, leading to subsequent downregulation of Fas, p55TNFR and Id3 protein (Figures 2, 3 and 7). Later, excess noggin inhibits interactions of BMP-2/4/7 or GDF-5 with BMPR-IB, resulting in a decrease of involucrin and loricrin expression, and retardation of cell differentiation in the eyelid epithelium (Figures 4, 5 and 7).

Our data suggest that important downstream components implicated in BMP-induced cell death, such as TAK1 and Msx-2 (Kimura et al., 2000; Gomes and Kessler, 2001), are not expressed in the eyelid epithelium (Figure 3) and, therefore, are most likely not involved in the alterations of apoptosis seen in the eyelid epithelium of K5-Noggin mice. Instead, we show here that BMP-mediated apoptosis in the eyelid epithelium may be achieved via recruitment of three other apoptotic regulators (Id3 protein, Fas and p55TNFR), whose expression is markedly reduced in eyelids of K5-Noggin mice (Figure 3).

Id3, a direct target of BMP-4 in mouse embryonic stem cells (Hollnagel et al., 1999), is highly expressed in the interdigital web, which is known to disappear during BMP-induced apoptosis (Zou and Niswander, 1996; Yokota, 2001; Guha et al., 2002). Fas and p55TNFR are implicated in the control of apoptosis during development in a large variety of cells including KCs (Wehrli et al., 2000). Our studies link for the first time the BMP-Smad signaling pathway with regulation of Fas and p55TNFR expression during development. Given that the Smad1 binding sequence (Kusanagi et al., 2000) is present in the promoters of both Fas and p55TNFR genes (Takao and Jacob, 1993; Zheng, 2001), Fas and p55TNFR may indeed be the targets for BMP-Smad regulation during eyelid opening.

Our data, which demonstrate a marked decrease of involucrin and loricrin in the eyelids of K5-Noggin mice (Figure 4) or in WT mice after administration of an adenoviral vector carrying a kinase-inactive form of BMPR-IB (Figure 5), are consistent with the presence of both Smad1- and Smad5-binding sequences (Kusanagi et al., 2000; Li et al., 2001) in the promoters of the involucrin and loricrin genes (Rothnagel et al., 1994; Gandarillas and Watt, 1995). Our data are also in agreement with data showing stimulatory effects of BMP-6 on epidermal differentiation (Blessing et al., 1996), and suggest that BMPs may promote KC differentiation at least in part by controlling the expression of involucrin and loricrin.

Our data also suggest that the effects of BMPs on cell apoptosis and differentiation during eyelid opening are most likely realized via recruitment of the BMP-Smad1/5 signaling pathway. Interestingly the two subtypes of BMPR-I appear to be differentially involved in the control of apoptosis (BMPR-IA) and cell differentiation (BMPR-IB) in developing eyelids. These results are consistent with observations published previously which demonstrate that in neuronal progenitors the expression of BMPR-IA precedes and stimulates the onset of BMPR-IB expression, which in turn promotes cellular differentiation (Panchison et al., 2001).

Most importantly, BMP-Smad and EGFR signaling appear to operate as two parallel pathways in regulating eyelid opening (Figure 6). The effects of the BMP-Smad signaling pathway on eyelid opening appear to be quite distinct from the effects of activin, the other member of the TGF-β superfamily, or its antagonist follistatin. Transgenic mice expressing either of these proteins under the control of the K14 promoter show precocious eyelid opening (Munz et al., 1999; Wankell et al., 2001). Interestingly, overexpression of Smad7, which may simultaneously inhibit TGF-β-, activin- and BMP-signal transduction pathways, also results in precocious eyelid opening (He et al., 2002). Taken together, these data suggest a high degree of complexity in regulation of eyelid opening by members of the TGF-β superfamily.

Interestingly, in contrast to K5-Noggin mice generated on a C3H/HeJ background, K14-Noggin mice generated on other genetic backgrounds (Guha et al., 2002) show no visible abnormalities in eyelid opening. This may be explained by the decreased expression and partial replacement of K14 by K15 in the developing eyelids (Figure 4), and is similar to that seen during esophagus development (Lloyd et al., 1995). Unlike K14, K5 expression in eyelid epidermis remains as strong as in back skin (Figure 4). These results suggest that K5 may possess a more suitable promoter for the study of eyelid biology. Alternatively, the differences in the phenotypes of the K5-Noggin and K14-Noggin mice may be explained by strain-dependent variability on the effects of BMPs on eyelid development. Indeed, the severity of the eye phenotype seen in BMP-7 null mice markedly increases on a C3H/He genetic background compared with a 129/Sv background (Wawersik et al., 1999).

Therefore, our data on inhibition of eyelid opening in K5-Noggin mice suggest a previously undiscovered role for BMP signaling in establishing contacts between the developing eye and the external environment. By regulating apoptosis and cellular differentiation in the eyelid epithelium, BMPs and noggin function as critically important players in the molecular program of skin remodeling during the final steps of eye morphogenesis.

Materials and methods

Generation of transgenic mice

C3H/HeJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were used as the background strain for generating K5-Noggin-overexpressing mice. Mice were housed in the community cages at the Transgenic Facility of the Boston University School of Medicine. The full-length mouse noggin cDNA was obtained from Dr R.Harland, and the Flag sequence was inserted at the 5′ end of the noggin cDNA. This cDNA was inserted into the expression cassette between the 1.69 kb human K5 promoter containing the β-globin intron and a transcription termination/polyadenylation [poly(A)] fragment of the human K14 gene (Ohtsuki et al., 1992). The 3.2 kb insert was separated from vector sequences, purified and injected into fertilized oocytes of C3H/HeJ mice at the Boston University Transgenic Facility. Mouse tail DNA was isolated, and TG founders were verified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-CTCTGTTGACAACCATTGTCTC and 5′-GCGGATGTGTAGATAG TGCTG (β-globin intron–noggin, 587 bp fragment), 5′-CAAAGACG ATGACGATAAAGAGCG and 5′-GCCCACCTTCACGTAGCGTG (flag-noggin–noggin, 559 bp fragment). To analyze the capacity of the transgene-derived noggin to inhibit BMP activity, the medium from either cultured TG or WT KCs (or 200 ng/ml noggin protein) was tested for its ability to neutralize osteoblast differentiation induced by 200 ng/ml BMP-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and monitored by alkaline phosphatase activity, as described previously (Aoki et al., 2001).

Adenoviral vectors

Adenoviruses carrying the hemagglutinin-tagged kinase-inactive forms of BMPR-IA/IB [AdAlk3(KR)/AdAlk6(KR)] or full-length Id3 cDNAs (AdId3) were generated by Dr K.Miyazono (Fujii et al., 1999) or by Dr C.McNamara (Matsumura et al., 2001). Adenoviruses were administered in concentrations up to 1 × 108 p.f.u. (50 µl) into the conjunctival sac of WT (n = 10) and TG mice (n = 10) at P1.5, P3.5 and P5.5. Control WT (n = 10) and TG mice (n = 10) were treated with adenoviruses carrying β-galactosidase. Animals were killed at P10.5–P13.5, and expression was monitored in frozen sections of eyelids by immunohistochemical detection of hemagglutinin or β-galactosidase using the corresponding rabbit antisera (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Eyelids were dissected from TG and WT mice (ages E18.5, P0.5–P34.5, n = 5–7 per time-point), quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, embedded into Tissue-Tek medium and cryosections were processed for different staining protocols. In situ hybridization using Dig-labeled riboprobes for BMP-2, BMP-4 and Msx-2 mRNAs was performed as described previously (Botchkarev et al., 2002). Immunohistochemical detection of BMPR-IA, BMPR-IB, Smad1, Smad5 and pSmad1/5 was performed with rabbit antisera against the corresponding antigens (ten Dijke et al., 1994; Ebisawa et al., 1999; Aoki et al., 2001). The sources and dilutions for antisera against Flag, TAK1, p21, Id1, Id2, Id3, EGFR, p38MAPK, K5, K10, K14, K15, filaggrin, involucrin, loricrin, p55TNFR, Fas, p75NTR and Edar are listed in Supplementary table 1 available at The EMBO Journal Online. Double immuno-visualization of TUNEL and Ki-67 was performed as described previously (Botchkarev et al., 1999). In all immunofluorescence procedures, nuclei were counterstained by TO-PRO-3. A multi-color confocal microscope (Zeiss) and digital image analysis system (Pixera) were used for analysis and preparation of images.

Western blot analysis

Total tissue proteins obtained from extracts of full-thickness eyelid or back skin of TG and WT mice at P0.5–P13.5 were collected in a lysis buffer, and protein concentrations were determined as described before (Botchkareva et al., 2001). Antibodies employed were anti-noggin, Flag, K5, K14 or K15. Horseradish peroxidase-tagged donkey anti-rabbit IgG was used as secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Semi-quantitative RT–PCR

Semi-quantitative RT–PCR analysis of p21, Id1/2/3, p75NTR, Fas, p55TNFR, filaggrin, involucrin, loricrin, BMP-7, GDF-5 and constitutively expressed β-actin was performed as previously described (Botchkarev et al., 2001). Total RNA was isolated from full-thickness eyelid skin samples of WT (n = 4) or TG mice (n = 4) at P0.5 and P10.5. For the experiments, RNA from individual animals was used, and the results were reproduced in three independent experiments using RNAs isolated from different animals. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription of 3 µg of total RNA, using a cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The oligonucleotide RT–PCR primers that were designed according to the reported sequences in the GenBank databases are listed in Supplementary table 2. Primers for Fas and p55TNFR were obtained from R&D Systems. Amplification was performed using Taq polymerase (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) over 30 cycles, using an automated thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). Each cycle consisted of denaturation at 92°C (1 min), annealing at 55–58°C (45 s) and extension at 72°C (45 s). PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and enzymatic digestion using standard methods.

Skin organ culture

Eyelid skin of the WT or TG mice was dissected at P7.5 and cultured as described previously (Botchkarev et al., 1999). Explants were cultured ex vivo for 96 h with addition of normal mouse serum (control), 100 ng/ml BMP-4, 200 ng/ml EGF or TGF-α (R&D Systems), or with a combination of BMP-4, EGF, TGF-α and 100 µM p38MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or 100 µM p44/p42MAPK inhibitor PD98059 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Medium was changed every 24 h. At the end of the incubation, all skin fragments were washed repeatedly in PBS buffer at 4°C, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and embedded into Tissue-Tek medium. Cryo-sections of skin explants were stained by hematoxylin, and the width of eyelid junction was determined using Pixera video-image system. Six WT or TG eyelid explants were used for every experimental group, all experiments were repeated three times, and mean ± SEM were evaluated. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analyses.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Drs R.Harland, A.P.McMahon, K.Miyazono, C.-M.Chuong and M.Pilkus are gratefully acknowledged for providing reagents and mice for this study. This study was supported by grants from the NIH to V.A.B. (AR47414; AR48573) and to J.L.B. (AR45284), as well as by grants from the CBRC through MGH/Shiseido Co. Ltd to J.L.B. and from the Swedish Medical Council to K.F.

References

- Aoki H., Fujii,M., Imamura,T., Yagi,K., Takehara,K., Kato,M. and Miyazono K. (2001) Synergistic effects of different bone morphogenetic protein type I receptors on alkaline phosphatase induction. J. Cell Sci., 114, 1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing M., Nanney,L., King,L., Jones,C. and Hogan,B.L. (1993) Transgenic mice as a model to study the role of TGF-β-related molecules in hair follicles. Genes Dev., 7, 204–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing M., Schirmacher,P. and Kaiser,S. (1996) Overexpression of bone morphogenetic protein-6 in the epidermis of transgenic mice: inhibition or stimulation of proliferation depending on the pattern of transgene expression and formation of psoriatic lesions. J. Cell Biol., 135, 227–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V.A. (2003) Bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists in skin and hair follicle biology. J. Invest. Dermatol., 120, 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V., Botchkareva,N., Roth,W., Nakamura,M., McMahon,J.A., McMahon,A. and Paus,R. (1999) Noggin is a mesenchymally-derived stimulator of hair follicle induction. Nat. Cell Biol., 1, 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V., Botchkareva,N., Nakamura,M., Huber,O., Funa,K., Lauster,R., Paus,R. and Gilchrest,B.A. (2001) Noggin is required for induction of hair follicle growth phase in postnatal skin. FASEB J., 15, 2205–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkarev V., Botchkareva,N., Huber,O., Funa,K. and Gilchrest,B.A. (2002) Modulation of BMP signaling by noggin is required for induction of the secondary (non-tylotrich) hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol., 118, 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkareva N., Khlgatian,M., Longley,B., Botchkarev,V. and Gilchrest,B.A. (2001) SCF/c-kit signaling is required for cyclic regeneration of hair pigmentation unit. FASEB J., 15, 645–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet L., McMahon,J., McMahon,A.P. and Harland,R.M. (1998) Noggin, cartilage morphogenesis and joint formation in the mammalian skeleton. Science, 280, 1455–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (1962) Isolation of a mouse submaxillary gland protein accelerating incisor eruption and eyelid opening in the newborn animal. J. Biol. Chem., 237, 1555–1562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisawa T., Tada,K., Kitajima,I., Miyazono,K. and Imamura,T. (1999) Characterization of bone morphogenetic protein-6 signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell Sci., 112, 3519–3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R.L., Crish,J., Banks,E. and Welter,J. (1997) The epidermis: genes on—genes off. J. Invest. Dermatol., 109, 501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlater G., McDougall,R. and Kaufman,M. (1993) Eyelid development, fusion and subsequent reopening in the mouse. J. Anat., 183, 121–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. and Raghavan,S. (2002) Getting under the skin of epidermal morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Genet., 3, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M. et al. (1999) Roles of bone morphogenetic protein type I receptors and Smad proteins in osteoblast and chondroblast differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell, 10, 3801–3813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandarillas A. and Watt,F.M. (1995) The 5′ noncoding region of the mouse involucrin gene: comparison with the human gene and genes encoding other cornified envelope precursors. Mamm. Genome, 6, 680–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes W. and Kessler,J.A. (2001) Msx-2 and p21 mediate the pro-apoptotic but not anti-proliferative effects of BMP4 on cultured sympathetic neuroblasts. Dev. Biol., 237, 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groppe J., Greenwald,J., Rodriguez-Leon,J., Economides,A., Affolter,M., Vale,W., Belmontes,J. and Choe,S. (2002) Structural basis of BMP signaling inhibiton by the cysteine knot protein Noggin. Nature, 420, 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha U., Gomes,W., Kobayashi,T., Pestell,R.G. and Kessler,J.A. (2002) In vivo evidence that BMP signaling is necessary for apoptosis in the mouse limb. Dev. Biol., 249, 108–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Li,A., Wang,D., Han,S., Zheng,B., Goumans,M.J., ten Dijke,P. and Wang,X. (2002) Overexpression of Smad7 results in severe pathological alterations in multiple epithelial tissues. EMBO J., 21, 2580–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B.L. (1996) Bone morphogenetic proteins: multifunctional regulators of vertebrate development. Genes Dev., 10, 1580–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B.L. (1999) Morphogenesis. Cell, 96, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel A., Oehlmann,V. and Nordheim,A. (1999) Id genes are direct targets of bone morphogenetic protein induction in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 19838–19845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura N., Matsuo,R., Nakashima,K. and Taga,T. (2000) BMP2-induced apoptosis is mediated by TAK1-p38 kinase pathway that is negatively regulated by Smad6. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 17647–17652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozawa O., Hatakeyama,D. and Uematsu,T. (2002) Divergent regulation by p44/p42 MAP kinase and p38 MAP kinase of bone morphogenetic protein-4-stimulated osteocalcin synthesis in osteoblasts. J. Cell. Biochem., 84, 583–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulessa H., Turk,G. and Hogan,B.L. (2000) Inhibition of Bmp signaling affects growth and differentiation in the anagen hair follicle. EMBO J., 19, 6664–6674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusanagi K., Inoue,H., Ishidou,Y., Mishima,H.K., Kawabata,M. and Miyazono,K. (2000) Characterization of a bone morphogenetic protein-responsive Smad-binding element. Mol. Biol. Cell, 11, 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Chen,F., Liu,X. and Chen,Y. (2001) Characterization of the DNA-binding property of Smad5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 286, 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C., Yu,Q.C., Turksen,K., Hutton,E. and Fuchs,E. (1995) The basal keratin network of stratified squamous epithelia: defining K15 functions in the absence of K14. J. Cell Biol., 129, 1329–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J. and Chen,Y. (2000) Controlling TGF-β signaling. Genes Dev., 14, 627–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura M., Li,F., Bertoux,L., Jeon,C. and McNamara,C.A. (2001) Vascular injury induces posttranscriptional regulation of the Id3 gene. Atheroscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 21, 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon J., Takada,S., Zimmerman,L., Fan,C., Harland,R.M. and McMahon,A.P. (1998) Noggin-mediated antagonism of BMP signaling is required for growth and patterning of the neural tube and somite. Genes Dev., 12, 1438–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K., Kusanagi,K. and Inoue,H. (2001) Divergence and convergence of TGF-β/BMP signaling. J. Cell. Physiol., 187, 265–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz B. et al. (1999) Overexpression of activin A in the skin of transgenic mice reveals new activities of activin in epidermal morphogenesis, dermal fibrosis and wound repair. EMBO J., 18, 5205–5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noramly S. and Morgan,B.A. (1998) BMPs mediate lateral inhibition at successive stages in feather tract development. Development, 125, 3775–3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki M., Tomic-Canic,M., Freedberg,I. and Blumenberg,M. (1992) Nuclear proteins involved in transcription of the human K5 keratin gene. J. Invest. Dermatol., 99, 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchison D., Pickel,J., Studer,L., Hazel,T. and McKay,R. (2001) Sequential action of BMP receptors control neural precursor cell production and fate. Genes Dev., 15, 2094–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothnagel J., Longley,M., Copeland,N. and Roop,D.R. (1994) Characterization of the mouse loricrin gene: linkage with profilaggrin and the flaky tail and soft coat mutant loci on chromosome 3. Genomics, 23, 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Sporn,M.A., Roberts,A. and Gregory,H. (1985) Human transforming growth factor-α causes precocious eyelid opening in newborn mice. Nature, 315, 515–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao S. and Jacob,C. (1993) Mouse tumor necrosis factor receptor type I: genomic structure, polymorphism and identification of regulatory regions. Int. Immunol., 5, 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J. (1985) Physiological effects of transforming growth factor in the newborn mouse. Science, 229, 673–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P., Yamashita,H., Sampath,T., Reddi,A., Estevez,M., Riddle,D., Ichijo,H., Heldin,C. and Miyazono,K. (1994) Identification of type I receptors for osteogenic protein-1 and bone morphogenetic protein-4. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 16985–16988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teraishi T. and Yoshioka,M. (2001) Electron-microscopic and immunohistochemical studies of eyelid reopening in the mouse. Anat. Embryol., 204, 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bubnoff A. and Cho,K. (2001) Intracellular BMP signaling regulation in vertebrates: pathway or network? Dev. Biol., 239, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wankell M., Munz,B., Hubner,G., Hans,W., Wolf,E., Goppelt,A. and Werner,S. (2001) Impaired wound healing in transgenic mice overexpressing the activin antagonist follistatin in the epidermis. EMBO J., 20, 5361–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawersik S., Purcell,P., Dudley,A., Robertson,E. and Maas,R. (1999) BMP7 acts in murine lens placode development. Dev. Biol., 207, 176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli P., Viard,I. and French,L. (2000) Death receptors in cutaneous biology and disease. J. Invest. Dermatol., 115, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota Y. (2001) Id and development. Oncogene, 20, 8290–8298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Wu,P., Widelitz,R. and Chuong,C.-M. (2002) The morphogenesis of feathers. Nature 420, 308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Chen,Q., Hung,F. and Overbeek,P.A. (2002) BMP signaling is required for development of the ciliary body. Development, 129, 4435–4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Ouaaz,F. and Beg,A. (2001) NF-κB RelA (p65) is essential for TNF-α-induced fas expression but dispensable for both TCR-induced expression and activation-induced cell death. J. Immunol., 166, 4949–4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman L., De Jesus Escobar,J. and Harland,R.M. (1996) The Spemann organizer signal noggin binds and inactivates bone morphogenetic protein 4. Cell, 86, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H. and Niswander,L. (1996) Requirement for BMP signaling in interdigital apoptosis and scale formation. Science, 272, 738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]