Abstract

The mammalian polypyrimidine-tract binding protein (PTB), which is a heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein, is ubiquitously expressed. Unexpectedly, we found that, in Drosophila melanogaster, the abundant PTB transcript is present only in males (third instar larval, pupal and adult stages) and in adult flies is restricted to the germline. Most importantly, a signal from the somatic sex-determination pathway that is dependent on the male-specific isoform of the doublesex protein (DSXM) regulates PTB, providing evidence for the necessity of soma–germline communication in the differentiation of the male germline. Analysis of a P-element insertion directly links PTB function with male fertility. Specifically, loss of dmPTB affects spermatid differentiation, resulting in the accumulation of cysts with elongated spermatids without producing fully separated motile sperms. This male-specific expression of PTB is conserved in D.virilis. Thus, PTB appears to be a particularly potent downstream target of the sex-determination pathway in the male germline, since it can regulate multiple mRNAs.

Keywords: hephaestus/male germline/PTB/sex determination/spermatogenesis

Introduction

In metazoans, the majority (85–95%) of genes contain intervening sequences or introns. A typical intron has several important splicing signals: the 5′ splice site, the 3′ splice site and the branch site. In higher eukaryotes, the polypyrimidine tract (Py-tract) upstream of the 3′ splice site is also an essential splicing signal (Burge et al., 1999; Reed, 2000). In plants, uridine-rich sequences that are present throughout introns appear to play a role in defining intron–exon boundaries (Lorkovic et al., 2000). Proper recognition of splicing signals is crucial for accurate splicing. Five small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6 snRNPs) and several other proteins recognize these signals and assemble onto a pre-mRNA to form a large complex called the spliceosome (Green, 1991; Moore et al., 1993; Will and Luhrmann, 1997; Nilsen, 2002). The assembly of the spliceosome involves several rearrangements, which include RNA–RNA, protein–protein and RNA–protein interactions (Staley and Guthrie, 1998). In the spliceosome, two transesterification reactions catalyze the joining of exons and removal of the lariat intron (Nilsen, 2000).

Alternative splicing is a process by which multiple mRNAs are synthesized from a single primary transcript, providing an excellent source of functional diversity (Lopez, 1998; Graveley, 2001). Preliminary estimates indicate that >35% of predicted human genes and 10–15% of Drosophila genes undergo alternative splicing (Mironov et al., 1999; Brett et al., 2002). Alternative splicing involves combinatorial use of alternative 5′ splice sites, 3′ splice sites, introns and exons (Lopez, 1998; Black, 2000; Smith and Valcarcel, 2000; Graveley, 2001; Singh, 2002). Although alternative splicing controls many important biological processes (Valcarcel et al., 1995), the somatic sex-determination pathway in Drosophila is thus far one of the best-understood examples of splicing regulation. In D.melanogaster, the key sex determining genes, Sex-lethal (Sxl), transformer (tra) and doublesex (dsx), are transcribed in an identical manner in both sexes. However, these transcripts are processed differently in male and female flies by alternative splicing (Cline and Meyer, 1996; Schutt and Nothiger, 2000). For example, in chromosomal males (XY), SXL and TRA proteins are not synthesized, due to in-frame translation stop codons in the mRNAs spliced by the default pathway. As a result, the male-specific isoform of the DSX protein (DSXM) is synthesized. However, in females (XX), alternative splicing allows synthesis of SXL and TRA proteins, leading to the synthesis of the female-specific isoform of DSX (DSXF). The DSXM isoform activates male-specific genes and represses female-specific genes in male flies, and the DSXF isoform activates female-specific genes and represses male-specific genes in female flies (Nagoshi and Baker, 1990; Burtis, 1993).

The Py-tract adjacent to the 3′ splice sites is an important target for splicing regulation (Smith and Valcarcel, 2000; Singh, 2002). For example, the Drosophila protein SXL blocks splice sites in target pre-mRNAs by binding to adjacent uridine-rich sequences or Py-tracts, leading to exon skipping in the Sxl pre-mRNA, 3′ splice site switching in the tra pre-mRNA and intron retention in the msl2 pre-mRNA. In contrast, the TRA protein, along with cofactors, binds to an exonic enhancer sequence(s) and activates an otherwise weak Py-tract/3′ splice site in the dsx pre-mRNA. The mammalian polypyrimidine-tract binding protein (PTB), another Py-tract binding protein, is also known as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein I (hnRNP I) (Ghetti et al., 1992); the hnRNP proteins are ubiquitously expressed, associate with nascent transcripts and play various roles in RNA metabolism (Krecic and Swanson, 1999). In vertebrates, transcripts from the PTB and brain-enriched PTB (brPTB) genes are widely expressed in many cell lines and tissues (Patton et al., 1991; Ashiya and Grabowski, 1997; Chan and Black, 1997; Polydorides et al., 2000). PTB was originally identified as a splicing factor and has four RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) (Gil et al., 1991; Patton et al., 1991). Subsequent studies, however, showed that the mammalian PTB has sequence-specific RNA-binding activity and can negatively regulate the splicing of a wide spectrum of pre-mRNAs, including muscle and neuronal transcripts (Mulligan et al., 1992; Lin and Patton, 1995; Singh et al., 1995; Ashiya and Grabowski, 1997; Chan and Black, 1997; Gooding et al., 1998; Wagner and Garcia-Blanco, 2001, 2002). The muscle- and neuron-specific splicing regulation of certain genes has been suggested to result from generalized repression of these genes by PTB in other cell types. Although SXL and PTB both compete for the binding of the general splicing factor U2AF65 to specific Py-tracts in repressing 3′ splice sites (Lin and Patton, 1995; Singh et al., 1995), the SXL protein, unlike PTB, is expressed only in the cell type or sex that shows alternative splicing. PTB is also known to control splice site choice by positive regulation of the pre-mRNA encoding the calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide (CT/CGRP) (Lou et al., 1999).

In addition to its role in splicing regulation, PTB can also regulate polyadenylation of the CT/CGRP pre-mRNA (Lou et al., 1996) and translation of RNAs from picornaviruses via internal ribosome entry sites (Kaminski et al., 1995; Valcarcel and Gebauer, 1997; Belsham and Sonenberg, 2000; Wagner and Garcia-Blanco, 2001). Previous studies with the vertebrate PTB were carried out using various assays in vitro or in cultured cells. Therefore, we analyzed PTB in Drosophila, where its function can be studied in a natural setting in vivo.

In this study, we have demonstrated, surprisingly, that an abundant Drosophila PTB (dmPTB) transcript is expressed only in the male germline and is regulated by the well-characterized somatic sex-determination pathway in a DSXM-dependent manner. Furthermore, molecular genetic analysis reveals that dmPTB function is essential for spermatogenesis during spermatid differentiation.

Results

An abundant PTB transcript is expressed only in males

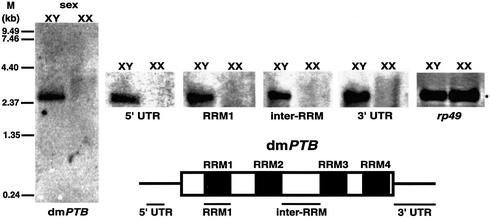

To analyze PTB function in vivo and complement studies with the vertebrate PTB, we investigated the Drosophila PTB. Unexpectedly, the D.melanogaster ortholog of PTB (dmPTB) was expressed in adult males but not females, as determined by northern analysis using the full-length cDNA probe (Figure 1, dmPTB); minor transcripts could be observed in females only upon longer exposure (data not shown). Since prior studies have not suggested that PTB has a sex-specific function or regulation, it remained possible that the abundant band in Figure 1 resulted from cross-hybridization via an RRM, a common highly conserved RNA-binding domain (Varani and Nagai, 1998). To exclude this possibility, we prepared several probes corresponding to divergent portions of the gene such as the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (5′ and 3′ UTRs) and the variable linker region between RRMs (inter-RRM). Each of the probes showed an identical male-specific signal (Figure 1). Consistent with this finding, BLAST results show that there is only one sequence match to the dmPTB cDNA (P-value 6.7e–290) in the Drosophila genome. These results confirm that this abundant mRNA expressed in adult males but not females is a genuine dmPTB transcript.

Fig. 1. An abundant male-specific transcript of dmPTB is expressed in adult male but not female flies. Northern analysis of dmPTB expression in wild-type (Oregon-R) male and female flies, using probes for either the full-length or various portions (5′ UTR, 3′ UTR, RRM1 and inter-RRM) of the dmPTB cDNA. For this and subsequent figures, XY and XX indicate chromosomal sex. Only relevant portions of the RNA blots are shown for the small probes. M, molecular size markers (kb); rp49, a loading control (the asterisk for the rp49 blot represents a 0.46 kb transcript).

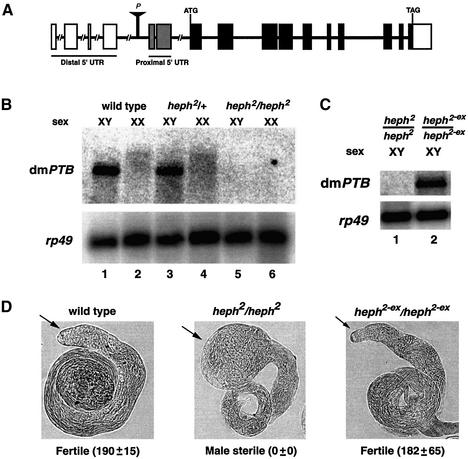

dmPTB function is essential for male fertility

Previously, a large-scale P-element insertion mutagenesis screen for male sterility identified the hephaestus2 (heph2) mutation (Castrillon et al., 1993), which was later mapped to the dmPTB locus by the Drosophila Genome Project (Spradling et al., 1999) (Figure 2A); other P-element insertions into the dmPTB locus are homozygous lethal (Dansereau et al., 2002). However, the molecular basis for the male sterility of the heph2 mutant was not studied. Since homozygosity for the heph2 allele causes sterility in male but not female flies (Castrillon et al., 1993), we reasoned that this phenotype might be due to the absence of the abundant male-specific dmPTB transcript. To directly test this hypothesis, we analyzed the expression of dmPTB in heph2 flies. The dmPTB transcript was present in both wild-type and heph2 heterozygous males (Figure 2B, lanes 1 and 3) but absent in heph2 homozygous males (lane 5). Thus, the heph2 P-element insertion disrupts the expression of the male-specific dmPTB transcript.

Fig. 2. P-element insertion in the dmPTB locus abolishes dmPTB expression. (A) Schematic of the dmPTB gene, adapted from GadFly. Boxes, exons; lines, introns; solid boxes, coding sequence; stippled/empty boxes, alternative 5′ UTR exons. Position (P) of the heph2 P-element is shown. (B) A P-element insertion abolishes dmPTB expression, based on northern analysis. Relevant genotypes are shown above the chromosomal sex. The dmPTB probe is inter-RRM (Figure 1). (C) Excision of the P-element restores dmPTB expression. Northern analysis of dmPTB expression in homozygous heph2 (lane 1) and heph2-ex (lane 2) strains. (D) Excision of the P-element restores gonad morphology and male fertility. Nomarski micrographs for male testes of given genotypes are shown. Arrows point to tips of the testes. The numbers in parentheses represent an average number, with standard deviation, of progeny from three independent matings involving 10 wild-type virgin females and 10 males of given genotypes, as described previously (Castrillon et al., 1993). Comparable dmPTB expression and fertility results were obtained from two additional excision lines.

To exclude the possibility that the heph2 insertion affected male sterility or dmPTB expression indirectly through unintended mutations, we excised the P-element using a standard protocol (Robertson et al., 1988). The excision of the P-element was confirmed by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA (see Supplementary figure 1 available at The EMBO Journal Online) and by the loss of the ry+ marker on the P-element. In the heph2-ex/heph2-ex male flies, excision of the P-element restored the male-specific expression of dmPTB (Figure 2C, lane 2). Consistent with previous results (Castrillon et al., 1993), the heph2 homozygous flies showed an enlarged tip of the testis (Figure 2D, heph2/heph2). However, the loss of the P-element reverted gonad morphology to normal (Figure 2D, heph2-ex/heph2-ex). In addition, excision of the P-element restored male fertility to the wild-type level (Figure 2D, bottom). These results confirm the authenticity of the abundant dmPTB mRNA and provide the first direct link between male fertility and PTB function.

The somatic sex-determination pathway regulates dmPTB expression

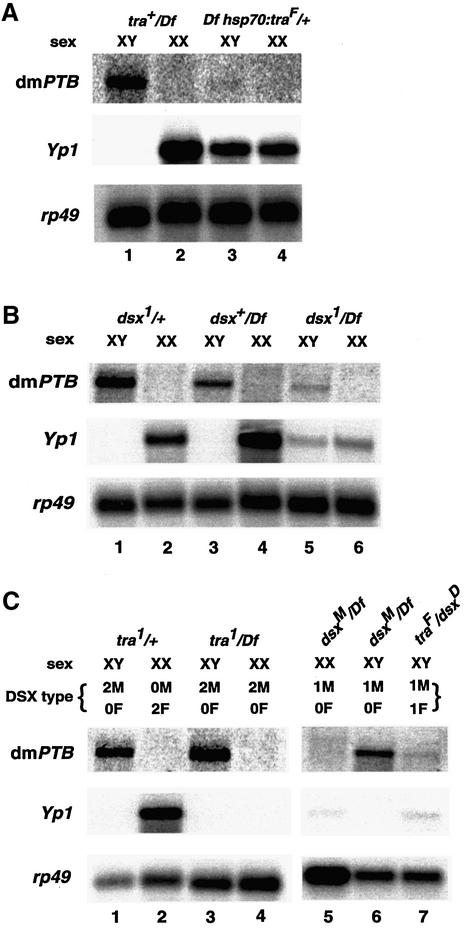

The male-specific expression of the abundant dmPTB transcript raised the possibility that it could be regulated by the well-characterized somatic sex-determination pathway (Sxl→tra→dsx) (Cline and Meyer, 1996; Schutt and Nothiger, 2000). To determine whether the somatic sex-determination pathway regulates dmPTB, we either ectopically expressed or used known mutations in tra or dsx. First, the ectopic synthesis of TRA in male flies, raised at 22°C using an hsp70::tra transgene, abolished expression of the male-specific dmPTB transcript (Figure 3A, top, lane 3); the presence of TRA was confirmed by somatic sexual transformation (McKeown et al., 1988; Nagoshi et al., 1988; Arthur et al., 1998; data not shown) and by the appearance of the female-specific Yolk protein 1 (Yp1) transcript (Figure 3A, middle, lane 3). Secondly, in dsx1/Df male flies (Burtis, 1993), the expression of the male-specific transcript of dmPTB was significantly reduced (∼90%) relative to dsx1/+ (Figure 3B, lanes 1 and 5). However, the loss of DSXF function in chromosomally female flies failed to activate the expression of dmPTB (Figure 3B, lane 6). These results show that the presence of DSXM is important for the activation of dmPTB, that loss of DSXF alone is insufficient for the activation and also argue against the possibility that a non-sex-specific factor alone activates dmPTB in males.

Fig. 3. The somatic sex-determination pathway regulates dmPTB expression. (A) Ectopic expression of TRA in chromosomal males represses dmPTB expression. Relevant genotypes are shown above the chromosomal sex. The dmPTB probe is inter-RRM, and Yp1 is a female-specific marker. (B) Loss of DSXM in XY flies greatly reduces the expression of the male-specific dmPTB transcript. (C) Expression of DSXM in XX flies is insufficient for activation of the dmPTB transcript, but feminization of the XY soma greatly reduces the dmPTB transcript in males. The DSX type indicates doses of the male-specific (M) and female-specific (F) forms of DSX. Both the dsxM and dsxD alleles synthesize only the DSXM isoform, irrespective of chromosomal sex (Nagoshi and Baker, 1990). Lane 6 is a mixture of dsxM/Df and dsx+/Df genotypes.

Next, we determined whether the male-specific function of dsx (DSXM) is sufficient for the activation of dmPTB. Surprisingly, expression of DSXM in chromosomally female flies was insufficient to activate dmPTB. First, the dsxM allele, which only expresses the DSXM isoform, did not activate dmPTB in XX flies (Figure 3C, lane 5) despite causing sexual transformation and disappearance of Yp1 (Figure 3C, middle) (Nagoshi and Baker, 1990; Burtis, 1993). Secondly, deletion of tra, which also mediates switching from the DSXF to the DSXM isoform in XX flies (McKeown et al., 1988; Nagoshi et al., 1988), also did not activate dmPTB (Figure 3C, lane 4). Finally, expression of DSXF, which is known to antagonize DSXM function (Burtis, 1993), did repress the DSXM-dependent activation of dmPTB in male flies (Figure 3C, lane 7). Thus, expression of the DSXM protein in XX flies is insufficient for the activation of dmPTB, and DSXF can prevent DSXM-dependent activation of dmPTB.

Expression of the abundant dmPTB transcript is restricted to the male germline

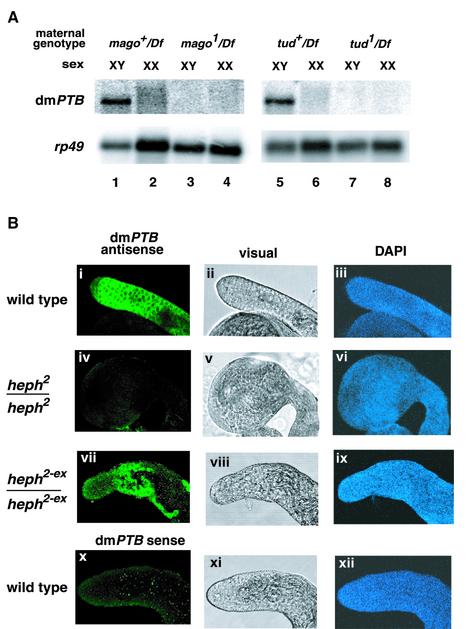

Our combined results show that the somatic sex-determination pathway in Drosophila controls dmPTB expression. Intriguingly, the XX flies that expressed the DSXM isoform and became somatically masculinized failed to express dmPTB (Figure 3C, lanes 4 and 5). These observations suggested that the abundant dmPTB transcript might be expressed in the germline, rather than in somatic cells. To distinguish between these possibilities, we analyzed the progeny of mago1/Df and tudor1/Df flies, which lacked a germline (Boswell and Mahowald, 1985; Boswell et al., 1991). Indeed, the dmPTB transcript was absent from the male progeny of mago1/Df and tudor1/Df flies (Figure 4A, lanes 3 and 7), indicating that the abundant dmPTB transcript is restricted to the male germline. Moreover, we directly confirmed by in situ hybridization that dmPTB was specifically expressed in primary spermatocytes in the wild-type (Figure 4B, i) and heph2-ex/heph2-ex testes (Figure 4B, vii) but not in the heph2/heph2 mutant testis (Figure 4B, iv). We conclude that the somatic sex-determination pathway controls the sex-specific expression of dmPTB in the male germline.

Fig. 4. The abundant dmPTB transcript is restricted to the male germline. (A) Loss of the male germline results in disappearance of the dmPTB transcript. Northern analysis was carried out using the inter-RRM probe. (B) Excision of the P-element restores dmPTB expression in the male germline. In situ hybridization and indirect immunofluorescence with testes from given genotypes were carried out using antisense (i, iv and vii) or sense (x) dmPTB probe (a negative control). DNA was stained with DAPI (iii, vi, ix and xii).

dmPTB is expressed from the late third instar larval stage through adult flies

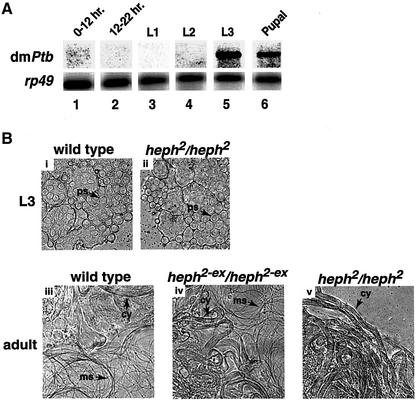

To determine the developmental regulation of dmPTB expression, we analyzed RNA blots from various stages of development. Figure 5A shows that the abundant transcript of dmPTB was not detectable in the embryonic (lanes 1 and 2), the first instar larval (lane 3) and the second instar larval (lane 4) stages of development. However, dmPTB was expressed in the late third instar larval (lane 5) and pupal (lane 6) stages of development. The expression of dmPTB at the L3 and the pupal stages is male specific (data not shown). We conclude that the abundant dmPTB transcript is expressed from L3 to adult stages.

Fig. 5. The dmPTB transcript is expressed from the third instar larval to adult stages and is important for spermatid maturation. (A) Northern analysis was carried out using the inter-RRM probe. 0–12 hr, early embryonic stage; 12–22 hr, late embryonic stage; L1, L2 and L3 are the first, second and late third instar larval stages, respectively. (B) The heph2 mutation affects spermatogenesis at or prior to sperm separation. L3 and adult refer to testes from the larval stage L3 and adults, respectively. Genotypes are indicated above each panel. Arrows refer to primary spermatocytes (ps), cysts with elongated spermatids (cy) and motile sperms (ms).

Loss of dmPTB affects spermatid differentiation

To determine how loss of dmPTB affects spermatogenesis, we analyzed wild-type and heph2/heph2 mutant testes. Figure 5B shows that there was no difference between the wild-type and the mutant germ cells in the larval stage L3, the earliest stage at which abundant expression of dmPTB was observed. In adults, all of the stages of spermatogenesis could be identified in the testes of wild-type (Figure 5B, iii) and excision flies (Figure 5B, iv). In particular, individual motile sperms were abundant. However, the heph2/heph2 mutant accumulated cysts of elongated spermatids, and the enlarged tips of these testes were also filled with such cysts (Figure 5B, v). In addition, the mutant lacked fully individualized motile sperms (Figure 5B, v). In the heph2/heph2 mutant, we could observe all of the morphogenetic stages up to elongated spermatids (for reference, see Fuller, 1993). We note that the majority of the elongated spermatids from the heph2 mutant showed numerous bulges along their tails characteristic of a defect during the individualization process (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that loss of dmPTB affects spermatid differentiation.

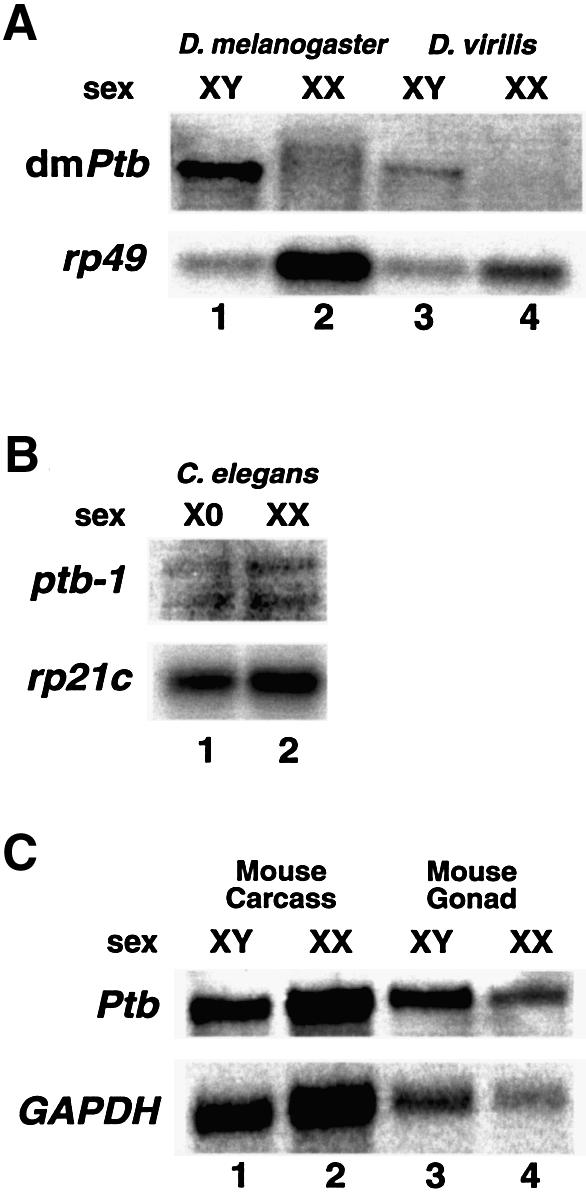

The male-specific expression of PTB is conserved in D.virilis

Next, we asked whether the sex-specific regulation of PTB is unique to D.melanogaster or is conserved in other organisms. We analyzed the expression of PTB in D.virilis, a distant relative of D.melanogaster. Figure 6A shows that PTB is unambiguously expressed in a male-specific manner in D.virilis (lanes 3 and 4); the weaker signal in D.virilis likely reflects imperfect complementarity with the D.melanogaster PTB sequence that was used for hybridization. We conclude that the sex-specific regulation of PTB has been conserved between D.virilis and D.melanogaster, which diverged 60 million years ago (Marin and Baker, 1998).

Fig. 6. The male-specific dmPTB transcript is also found in adult D.virilis. (A) An RNA blot using D.melanogaster and D.virilis RNA from male and female flies was probed using the entire dmPTB cDNA probe. The weaker signal in D.virilis likely reflects imperfect complementarity with the D.melanogaster PTB sequence that was used for hybridization. (B) PTB is expressed in both sexes in C.elegans. XO, him-8 males (lane 1); XX, N2 gravid hermaphrodites in which spermatogenesis has ceased (lane 2). Ribosomal protein gene (rp21c) is a loading control. (C) PTB is expressed in both sexes in mouse embryos. XY carcass (whole embryo lacking gonads) (lane 1); XX carcass (lane 2); XY gonads (13.5 days old) (lane 3); XX gonads (13.5 days old) (lane 4). Glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) is a loading control.

Although components upstream in the sex-determination pathway have significantly diverged, dsx and likely its downstream functions are conserved (Raymond et al., 1998; Zarkower, 2002). For example, the male-specific isoform of dsx (DSXM) can functionally substitute for the mab-3 gene in directing male-specific neuroblast differentiation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Raymond et al., 1998). Both proteins contain the conserved DNA-binding motif (DM domain) that is also found in the human and the murine orthologs: the human DMT1 gene is expressed only in testes, and the murine Dmrt1 gene is essential for testis differentiation but dispensable for ovarian development (Raymond et al., 2000).

Since dmPTB responds to the function of the male-specific isoform of dsx, we asked whether the sex-specific expression of dmPTB is also conserved in C.elegans and mouse. Figure 6B shows that both hermaphrodite (XX) and male (XO) worms expressed comparable levels of PTB transcripts. In addition, PTB was equally expressed in the carcass (Figure 6C, lanes 1 and 2) and gonads (lanes 3 and 4) of both sexes in 13.5-day-old mouse embryos, the stage at which testes and ovaries can be easily distinguished. We conclude that, although the PTB mRNA is equally expressed in both sexes in worms and mouse, the abundant dmPTB transcript is restricted to males in D.melanogaster and D.virilis.

Discussion

This study provides the first evidence that there is a major male-specific transcript of the Drosophila PTB that is regulated by the somatic sex-determination pathway. The sex-specific function of the abundant dmPTB transcript reported here is restricted to the male germline. Finally, we provide a direct molecular link between male fertility and PTB function, which offers a molecular basis for the male sterility of the heph2 mutant.

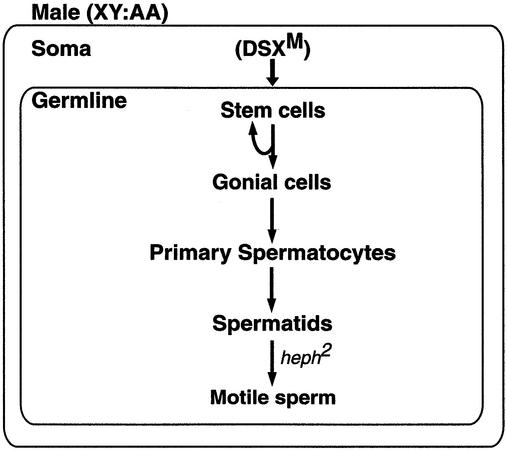

Model for dmPTB regulation

We postulate that the somatic sex-determination pathway, in a DSXM-dependent manner, provides a signal for the proliferation and differentiation of male germ cells, leading to the expression of dmPTB in the male germline (Figure 7). Since tra and dsx are dispensable within the germline (Marsh and Wieschaus, 1978; Schupbach, 1982), their effect from the somatic tissue is inductive in nature (Steinmann-Zwicky et al., 1989; Steinmann-Zwicky, 1994; Heller and Steinmann-Zwicky, 1998; Waterbury et al., 2000; Janzer and Steinmann-Zwicky, 2001). Accordingly, the DSXF isoform in the female soma or lack of the DSXM isoform in the male soma would fail to provide an appropriate signal for the development of the male germ cells. Thus, dmPTB expression is indirectly regulated by DSXM in the male germline.

Fig. 7. A model for the sex-specific function of dmPTB in the male germline. A DSXM-dependent inductive signal from the male soma is necessary for germ cell proliferation or maintenance and thus dmPTB expression. The dmPTB transcript is abundant in primary spermatocytes. The heph2 mutation affects spermatid differentiation, resulting in the accumulation of cysts with elongated spermatids but lacking fully separated motile sperms. Briefly, spermatogenesis involves division of stem cells to regenerate themselves and produce gonial cells. Each gonial cell mitotically divides four times to produce 16 primary spermatocytes enclosed in a cyst of two somatically derived cells. The primary spermatocytes undergo two meiotic divisions to generate 64 spermatids, which undergo a series of morphogenetic changes culminating in fully separated motile sperms (for a detailed description of spermatogenesis, see figure 9 in Fuller, 1993).

There are several differences in the mechanism of sex determination between somatic cells and the female germline (Steinmann-Zwicky, 1992; Mahowald and Wei, 1994; Cline and Meyer, 1996; Schutt and Nothiger, 2000), e.g. the mechanism by which the X:A ratio is sensed is different between the two cell types. Furthermore, sexual differentiation is entirely cell autonomous in somatic cells but also requires a somatic inductive signal(s) in germ cells (Steinmann-Zwicky, 1994; Heller and Steinmann-Zwicky, 1998; Waterbury et al., 2000; Janzer and Steinmann-Zwicky, 2001). We emphasize that, unlike other male-specific transcripts that are either functional in somatic cells or dispensable for germline sex determination and spermatogenesis (Cann et al., 2000; Ahmad and Baker, 2002; Streit et al., 2002), dmPTB function is necessary in the germline for spermatogenesis. Thus, dmPTB provides evidence for the necessity of soma– germline communication in the differentiation of the male germline.

Several interesting aspects of dmPTB regulation, however, remain to be addressed. For example, relatively little is known about the molecular nature of somatic- or germline-specific activation signals for dmPTB expression. Also, we cannot distinguish whether the relevant germline-specific signal is repressed in the female germline or is activated only in the male germline (Heller and Steinmann-Zwicky, 1998). Finally, the promoter element(s) that confer male germline-specific expression remains unknown.

Male-germline-specific versus non-sex-specific functions of dmPTB

The male-germline-specific function of the abundant dmPTB transcript reported here directly links dmPTB function to male fertility. Specifically, dmPTB is expressed in primary spermatocytes and affects spermatid differentiation, resulting in the accumulation of cysts with elongated spermatids, but fully separated motile sperms are not observed. This phenotype is reminiscent of the defect seen in late male-sterile mutants such as the individualization-deficient clathrin heavy chain (Chc) mutant (Fabrizio et al., 1998), suggesting that dmPTB may control a component(s) of the cytoskeletal machinery. The expression pattern of dmPTB is consistent with the observation that the majority of transcription in germ cells is limited to the premeiotic stages, although protein synthesis and significant morphological changes occur during postmeiotic spermatid differentiation (Fuller, 1993). Accordingly, we favor that dmPTB is expressed early during spermatogenesis but affects either directly or indirectly the events that occur or manifest late during spermatid differentiation (Fuller, 1993). We emphasize that many male-sterile mutants are known to show secondary effects even though such mutations affect processes early during spermatogenesis (for further discussion, see p. 115 in Fuller, 1993). Thus, dmPTB in the male germline may control multiple targets or steps during spermatogenesis. Consistent with the known RNA-binding functions of the mammalian PTB (Valcarcel and Gebauer, 1997), it could regulate the splicing, polyadenylation or translation of potential mRNAs that participate in spermatogenesis.

The male-germline-specific function of dmPTB is not necessarily inconsistent with the ubiquitous expression and multiple known targets of the vertebrate PTB (Valcarcel and Gebauer, 1997). To reconcile these differences, we favor that dmPTB performs an additional non-sex-specific function(s) vital for both sexes in Drosophila. First, the male-sterile heph2 mutant also affects viability of both sexes (M.D.Robida and R.Singh, unpublished results). Secondly, other mutations in the dmPTB locus are homozygous lethal (Dansereau et al., 2002). The most likely explanation for the different phenotypes of these mutations is that, whereas the heph2 mutation perturbs the male germline function but partially supports the vital function, the ema mutation compromises both functions. Thirdly, based on in situ hybridizations, dmPTB transcripts are expressed in several cell lineages (Davis et al., 2002), and minor transcripts are observed in females only upon longer exposure (M.D.Robida and R.Singh, unpublished results).

Given that the dmPTB locus is large (>135 kb) and that there is an indication of two distinct 5′ UTRs (distal and proximal) (Figure 2A) (Davis et al., 2002), the simplest interpretation for the two phenotypes is that the abundant male germline-specifc transcript reported here corresponds to an mRNA that contains the distal 5′ UTR (Figure 1, 5′ UTR probe) and is likely transcribed from an upstream promoter (Figure 2A). Accordingly, we favor that a downstream promoter(s) possibly contributes low abundance transcript(s) that are expressed non-sex- specifically in many cell lineages (Davis et al., 2002). This situation is reminiscent of two types of Sxl transcripts arising from a sex-specific establishment promoter (Pe) that is transiently active early during development (blastoderm stage) in females and from a non-sex-specific maintenance promoter (Pm) that is active in both sexes later during development (Keyes et al., 1992). Although PTB transcripts are expressed in both male and female gonads in mice and worms (Figure 6B and C), we cannot exclude the possibility that the PTB protein is functional only in the male germline or regulates male-germline- specific mRNA(s) in the gonads of these organisms.

Biological significance

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that hnRNP proteins (Krecic and Swanson, 1999; Elliott et al., 2000), which are generally widely expressed, can serve a sex-specific function in vivo. In addition, these studies provide molecular evidence that an appropriate somatic sex-determination signal is required for proper differentiation of the male germline, and dmPTB provides a useful reagent to define interactions between soma and the male germline for proper male germline differentiation. Finally, dmPTB, which is needed for fertility and spermatogenesis, is potentially an important downstream target of the sex-determination cascade in the male germline, where it could regulate multiple mRNAs.

Materials and methods

Fly strains and culture

The heph2/TM3, Df(3R)dsx3/TM3, dsx1/TM3, dsxM/TM1, tra1/TM2, Df(3L)st7/TM3 & betaTub85DD/TM2 and dsxD/TM2 stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. The Df(3L)stJ7/TM6B and Df(3L)stJ7 hsp70:traF/TM6B stocks were obtained from Barbara Taylor and the Df(1)H3g6/FM7c, Df(2R)Puf36/SM5 (deficiency of mago), mago1/SM6a, Df(2R)PF1/SM6a (deficiency of tudor), tud1/CyO and D.virilis stocks from Bob Boswell. The dsxM/dsx+ and dsxM/Df flies were generated as follows: dsxM/TM1 males were crossed to Df(3R)dsx3/TM3 females, and dsxM/TM3 male progeny were collected and mated to Df(1)H3gb/FM7c. The Fm7c/Y; dsxM/dsx+ male progeny were collected and mated to XX;Df(3R)dsx3/TM3 flies. dsxM/dsx+ and dsxM/Df progeny were phenotypically separated. The dsx1/Df flies were obtained by crossing BsY;dsx1/TM3 and XX;Df(3R)dsx3/TM3; the traF/dsxD flies by crossing XX;Df(3L)stJ7 hsp70:traF/TM6B and XY;dsxD/TM2; the mago1/Df flies by crossing Df(2R)Puf36/SM5 and mago1/SM6a; and the tud1/Df flies by crossing Df(2R)PF1/SM6a and tud1/CyO. The BsY;tra1/TM3 stock was obtained by crossing BsY;dsx1/TM3 with XX;tra1/TM2 flies. The tra1/Df flies were obtained by crossing BsY;tra1/TM3 with XX;Df(3L)st7/TM3. All TM3 balancer chromosomes carried the Sb1 marker. The heph2/heph2 larvae were obtained from a heph2/TM6B,Tb stock. Flies were raised on standard corn meal food at 25°C (Ashburner, 1989). The heph2/TM3 flies were raised at 22°C, and those carrying the traF cDNA were raised at 22°C on Formula 4-24 Plain Instant Drosophila Medium (Carolina Biologicals, NC) containing 0.27 mg/ml geneticin (Invitrogen, CA).

Caenorhabditis elegans culture and isolation

Worm strains were as described previously (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988). The XO him-8 males were obtained by filtering through nylon screens and the N2 gravid hermaphrodites were isolated by a 35% sucrose float (Lewis and Fleming, 1995).

DNA clones and probes

The cDNA clones for rp49 (GH27246), Yp1 (GH28744) and dmPTB (LD03431) and the mouse Ptb (IMAGE 480448) were obtained from Research Genetics (CA). The C.elegans ptb-1 clone (yk1128d03) was obtained from Dr Yuji Kohara. The rp21c DNA was obtained from Dr Tom Blumenthal. The GAPDH (glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) plasmid was obtained from Gennyne Walker. The smaller dmPTB probes were prepared using the following sets of primers: distal 5′ UTR, forward (5′-AGTGAATAAATTATCAACGTGTGC-3′) and reverse (5′-TTTCTTTTTCCTCGTAGTGCAAC-3′); 3′ UTR, forward (5′-AATCCGATGCGAAGTCAGGTTT-3′) and reverse (5′-AATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′); CDS1, forward (5′-GCCAAGGCCTCAAAAGTCATC-3′) and reverse (5′-GTTGTGACCTTGGTCCGTCTT-3′); and CDS2, forward (5′-TGTTAAGTACAACAACGACAAATC-3′) and reverse (5′-TCGAGTAACCTCGCATTGCAG-3′).

Northern analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, MO). Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated using the PolyATtract mRNA isolation system (Promega, WI). For each lane, ∼0.5–1.0 µg of poly(A)+ RNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel with formaldehyde. RNA was transferred to a Duralose-UV membrane (Stratagene, CA), hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe at 42°C overnight, washed extensively and imaged on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

P-element excision

The P-element (BDGP:ms(3)10515) causing the heph2 phenotype was excised using a standard transposase source (Robertson et al., 1988). The excision lines were analyzed by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA using appropriate primer pairs. The primers used were: 1, 5′-CGGGATCCTTGTTCTTGTAACAGCAATTGTTG-3′; 2, 5′-AACTGCAGTTAGAGCGAACTAGCGGAGAAT-3′; and 3, 5′-CAATCATATCGC TGTCTCACTCA-3′. The PCR was performed as follows: 94°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, 72°C for 1 min and one cycle of 72°C for 7 min, using a 50 µl reaction containing 1× MgCl2-free PCR buffer (Promega), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM dNTPs, 1 µM each primer and genomic DNA equivalent of two flies. The PCR product was separated on an agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

In situ hybridization

Testes were excised from adult males and fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and Tween-20 (PBST: 0.137 M NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.47 mM KH2PO4, 0.1% Tween-20). Testes were washed for 10 min in 20 mg/ml glycine with PBST and stored overnight at –20°C in methanol. The samples were rehydrated in PBST, permeabilized for 2 h in 1% Triton X-100 in PBST, post-fixed for 5 min, washed for 10 min in the glycine solution and then washed extensively with PBST. They were hybridized overnight in 50% deionized formamide, 5× SSC, 0.2 mg/ml sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 0.1 mg/ml tRNA and 0.05 mg/ml heparin at 65°C with the full-length dmPTB (antisense or sense) RNA labeled with fluorescein (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Samples were washed with PBST, incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature with 1:100 dilution of an anti-fluorescein rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes A-889) in PBST/2% BSA, followed by 1:250 dilution of a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody coupled to an Alexa 488 flour (Molecular Probes A-11034) in PBST/2% BSA, and washed with PBST. For the detection of DNA, the testes were then incubated with DAPI (1 µg/ml) in PBST for 10 min and washed 6 × 10 min with PBST. Testes were mounted in 70% glycerol/PBS and viewed using a Leica Confocal microscope.

Testes squashes

Testes from L3 larvae or adults were dissected in 1× PBST and placed on a slide in a drop of 1× PBST. A cover slip was overlayed to squash the testes. The resulting squashes were viewed using phase-contrast miscrosopy on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Tom Cech, Tom Blumenthal, Bob Boswell, Jens Lykke-Anderson, Mark Winey and members of the Singh laboratory for critical comments on the manuscript; Dan Starr for help with the microscopic analysis of spermatogenesis; Barbara Taylor and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for providing the fly stocks; Dr Bob Boswell and P.J.Bennett for advice on fly genetics and fly stocks; Dr Brian Parr for the mouse RNA; Drs Peg MacMorris and Tom Blumenthal for the ribosomal protein gene; and Barb Robertson and Dr Bill Wood for help with the worm RNA. M.D.R. thanks Kellie Hazell for her support. This work was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health to M.D.R. and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM58576) to R.S.

References

- Ahmad S.M. and Baker,B.S. (2002) Sex-specific deployment of FGF signaling in Drosophila recruits mesodermal cells into the male genital imaginal disc. Cell, 109, 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur B.I. Jr, Jallon,J.M., Caflisch,B., Choffat,Y. and Nothiger,R. (1998) Sexual behaviour in Drosophila is irreversibly programmed during a critical period. Curr. Biol., 8, 1187–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M. (1989) Drosophila: A Laboratory Manual, Vol. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Ashiya M. and Grabowski,P.J. (1997) A neuron-specific splicing switch mediated by an array of pre-mRNA repressor sites: evidence of a regulatory role for the polypyrimidine tract binding protein and a brain-specific PTB counterpart. RNA, 3, 996–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsham G.J. and Sonenberg,N. (2000) Picornavirus RNA translation: roles for cellular proteins. Trends Microbiol., 8, 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D.L. (2000) Protein diversity from alternative splicing: a challenge for bioinformatics and post-genome biology. Cell, 103, 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell R.E. and Mahowald,A.P. (1985) tudor, a gene required for assembly of the germ plasm in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell, 43, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell R.E., Prout,M.E. and Steichen,J.C. (1991) Mutations in a newly identified Drosophila melanogaster gene, mago nashi, disrupt germ cell formation and result in the formation of mirror-image symmetrical double abdomen embryos. Development, 113, 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett D., Pospisil,H., Valcarcel,J., Reich,J. and Bork,P. (2002) Alternative splicing and genome complexity. Nat. Genet., 30, 29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C.B., Tuschl,T. and Sharp,P.A. (1999) Splicing of precursors to mRNAs by the spliceosomes. In Gesteland,R.F., Cech,T.R. and Atkins,J.F. (eds), The RNA World, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 525–560.

- Burtis K.C. (1993) The regulation of sex determination and sexually dimorphic differentiation in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 5, 1006–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann M.J., Chung,E. and Levin,L.R. (2000) A new family of adenylyl cyclase genes in the male germline of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Genes Evol., 210, 200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillon D.H., Gonczy,P., Alexander,S., Rawson,R., Eberhart,C.G., Viswanathan,S., DiNardo,S. and Wasserman,S.A. (1993) Toward a molecular genetic analysis of spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster: characterization of male-sterile mutants generated by single P element mutagenesis. Genetics, 135, 489–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R.C. and Black,D.L. (1997) The polypyrimidine tract binding protein binds upstream of neural cell-specific c-src exon N1 to repress the splicing of the intron downstream. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 4667–4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline T.W. and Meyer,B.J. (1996) Vive la difference: males vs females in flies vs worms. Annu. Rev. Genet., 30, 637–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau D.A., Lunke,M.D., Finkielsztein,A., Russell,M.A. and Brook,W.J. (2002) hephaestus encodes a polypyrimidine tract binding protein that regulates Notch signalling during wing development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development, 129, 5553–5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.B., Sun,W. and Standiford,D.M. (2002) Lineage-specific expression of polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) in Drosophila embryos. Mech. Dev., 111, 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D.J., Venables,J.P., Newton,C.S., Lawson,D., Boyle,S., Eperon,I.C. and Cooke,H.J. (2000) An evolutionarily conserved germ cell-specific hnRNP is encoded by a retrotransposed gene. Hum. Mol. Genet., 9, 2117–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio J.J., Hime,G., Lemmon,S.K. and Bazinet,C. (1998) Genetic dissection of sperm individualization in Drosophila melanogaster. Development, 125, 1833–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller M.T. (1993) Spermatogenesis. In Bate,M. and Arias,A.M. (eds), The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, Vol. I. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 71–147.

- Ghetti A., Pinol-Roma,S., Michael,W.M., Morandi,C. and Dreyfuss,G. (1992) hnRNP I, the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein: distinct nuclear localization and association with hnRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 3671–3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil A., Sharp,P.A., Jamison,S.F. and Garcia-Blanco,M.A. (1991) Characterization of cDNAs encoding the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein. Genes Dev., 5, 1224–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding C., Roberts,G.C. and Smith,C.W. (1998) Role of an inhibitory pyrimidine element and polypyrimidine tract binding protein in repression of a regulated α-tropomyosin exon. RNA, 4, 85–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley B.R. (2001) Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends Genet., 17, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.R. (1991) Biochemical mechanisms of constitutive and regulated pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol., 7, 559–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller A. and Steinmann-Zwicky,M. (1998) In Drosophila, female gonadal cells repress male-specific gene expression in XX germ cells. Mech. Dev., 73, 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzer B. and Steinmann-Zwicky,M. (2001) Cell-autonomous and somatic signals control sex-specific gene expression in XY germ cells of Drosophila. Mech. Dev., 100, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski A., Hunt,S.L., Patton,J.G. and Jackson,R.J. (1995) Direct evidence that polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) is essential for internal initiation of translation of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA. RNA, 1, 924–938. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes L.N., Cline,T.W. and Schedl,P. (1992) The primary sex determination signal of Drosophila acts at the level of transcription. Cell, 68, 933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krecic A.M. and Swanson,M.S. (1999) hnRNP complexes: composition, structure, and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J.A. and Fleming,J.T. (1995) Basic culture methods. In Epstein,H.F. and Shakes,D.C. (eds), Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 4–27.

- Lin C.H. and Patton,J.G. (1995) Regulation of alternative 3′ splice site selection by constitutive splicing factors. RNA, 1, 234–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez A.J. (1998) Alternative splicing of pre-mRNA: developmental consequences and mechanisms of regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet., 32, 279–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorkovic Z.J., Wieczorek Kirk,D.A., Lambermon,M.H. and Filipowicz,W. (2000) Pre-mRNA splicing in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci., 5, 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H., Gagel,R.F. and Berget,S.M. (1996) An intron enhancer recognized by splicing factors activates polyadenylation. Genes Dev., 10, 208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H., Helfman,D.M., Gagel,R.F. and Berget,S.M. (1999) Poly pyrimidine tract-binding protein positively regulates inclusion of an alternative 3′-terminal exon. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald A.P. and Wei,G. (1994) Sex determination of germ cells in Drosophila. Ciba Found. Symp., 182, 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin I. and Baker,B.S. (1998) The evolutionary dynamics of sex determination. Science, 281, 1990–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J.L. and Wieschaus,E. (1978) Is sex determination in germ line and soma controlled by separate genetic mechanisms? Nature, 272, 249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown M., Belote,J.M. and Boggs,R.T. (1988) Ectopic expression of the female transformer gene product leads to female differentiation of chromosomally male Drosophila. Cell, 53, 887–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov A.A., Fickett,J.W. and Gelfand,M.S. (1999) Frequent alternative splicing of human genes. Genome Res., 9, 1288–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.J., Query,C.C. and Sharp,P.A. (1993) Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In Gesteland,R.F. and Atkins,J.F. (eds), The RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 303–357.

- Mulligan G.J., Guo,W., Wormsley,S. and Helfman,D.M. (1992) Polypyrimidine tract binding protein interacts with sequences involved in alternative splicing of β-tropomyosin pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 25480–25487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi R.N. and Baker,B.S. (1990) Regulation of sex-specific RNA splicing at the Drosophila doublesex gene: cis-acting mutations in exon sequences alter sex-specific RNA splicing patterns. Genes Dev., 4, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi R.N., McKeown,M., Burtis,K.C., Belote,J.M. and Baker,B.S. (1988) The control of alternative splicing at genes regulating sexual differentiation in D.melanogaster. Cell, 53, 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen T.W. (2000) The case for an RNA enzyme. Nature, 408, 782–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen T.W. (2002) The spliceosome: no assembly required? Mol. Cell, 9, 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J.G., Mayer,S.A., Tempst,P. and Nadal-Ginard,B. (1991) Characterization and molecular cloning of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein: a component of a complex necessary for pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev., 5, 1237–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polydorides A.D., Okano,H.J., Yang,Y.Y., Stefani,G. and Darnell,R.B. (2000) A brain-enriched polypyrimidine tract-binding protein antagonizes the ability of Nova to regulate neuron-specific alternative splicing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6350–6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond C.S., Shamu,C.E., Shen,M.M., Seifert,K.J., Hirsch,B., Hodgkin,J. and Zarkower,D. (1998) Evidence for evolutionary conservation of sex-determining genes. Nature, 391, 691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond C.S., Murphy,M.W., O’Sullivan,M.G., Bardwell,V.J. and Zarkower,D. (2000) Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Genes Dev., 14, 2587–2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. (2000) Mechanisms of fidelity in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 12, 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H.M., Preston,C.R., Phillis,R.W., Johnson-Schlitz,D.M., Benz,W.K. and Engels,W.R. (1988) A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics, 118, 461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupbach T. (1982) Autosomal mutations that interfere with sex determination in somatic cells of Drosophila have no direct effect on the germline. Dev. Biol., 89, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt C. and Nothiger,R. (2000) Structure, function and evolution of sex-determining systems in Dipteran insects. Development, 127, 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. (2002) RNA–protein interactions that regulate pre-mRNA splicing. Gene Expr., 10, 79–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Valcarcel,J. and Green,M.R. (1995) Distinct binding specificities and functions of higher eukaryotic polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins. Science, 268, 1173–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.W. and Valcarcel,J. (2000) Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: the logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A.C., Stern,D., Beaton,A., Rhem,E.J., Laverty,T., Mozden,N., Misra,S. and Rubin,G.M. (1999) The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project gene disruption project: single P-element insertions mutating 25% of vital Drosophila genes. Genetics, 153, 135–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley J.P. and Guthrie,C. (1998) Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell, 92, 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M. (1992) How do germ cells choose their sex? Drosophila as a paradigm. BioEssays, 14, 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M. (1994) Sex determination of the Drosophila germ line: tra and dsx control somatic inductive signals. Development, 120, 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M., Schmid,H. and Nothiger,R. (1989) Cell-autonomous and inductive signals can determine the sex of the germ line of Drosophila by regulating the gene Sxl. Cell, 57, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit A., Bernasconi,L., Sergeev,P., Cruz,A. and Steinmann-Zwicky,M. (2002) mgm1, the earliest sex-specific germline marker in Drosophila, reflects expression of the gene esg in male stem cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol., 46, 159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J. and Hodgkin,J. (1988) Methods. In Wood,W.W. (ed.), The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 587–606.

- Valcarcel J. and Gebauer,F. (1997) Post-transcriptional regulation: the dawn of PTB. Curr. Biol., 7, R705–R708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel J., Singh,R. and Green,M.R. (1995) Mechanisms of Regulated Pre-mRNA Splicing. The R.G. Landes Company, Biomedical Publisher, Austin, TX.

- Varani G. and Nagai,K. (1998) RNA recognition by RNP proteins during RNA processing. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 27, 407–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E.J. and Garcia-Blanco,M.A. (2001) Polypyrimidine tract binding protein antagonizes exon definition. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 3281–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E.J. and Garcia-Blanco,M.A. (2002) RNAi-mediated PTB depletion leads to enhanced exon definition. Mol. Cell, 10, 943–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterbury J.A., Horabin,J.I., Bopp,D. and Schedl,P. (2000) Sex determination in the Drosophila germline is dictated by the sexual identity of the surrounding soma. Genetics, 155, 1741–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will C.L. and Luhrmann,R. (1997) Protein functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 9, 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkower D. (2002) Invertebrates may not be so different after all. Novartis Found. Symp., 244, 115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]