Abstract

Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (PLC) is a key enzyme in phosphoinositide turnover and is involved in a variety of physiological functions. Here we report that PLCδ1-deficient mice undergo progressive hair loss in the first postnatal hair cycle. Epidermal hyperplasia was observed, and many hairs in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice failed to penetrate the epidermis and became zigzagged owing to occlusion of the hair canal. Two major downstream signals of PLC, calcium elevation and protein kinase C activation, were impaired in the keratinocytes and skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice. In addition, many cysts that had remarkable similarities to interfollicular epidermis, as well as hyperplasia of sebaceous glands, were observed. Furthermore, PLCδ1-deficient mice developed spontaneous skin tumors that had characteristics of both interfollicular epidermis and sebaceous glands. From these results, we conclude that PLCδ1 is required for skin stem cell lineage commitment.

Keywords: differentiation/PLC/skin stem cell

Introduction

Phospholipase C (PLC) hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate two second messengers: diacylglycerol (DG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). DG mediates the activation of protein kinase C (PKC), and IP3 releases calcium from intracellular stores (Berridge and Irvine, 1984; Nishizuka, 1988). PLC can be categorized into four types, β, γ, δ and ε, on the basis of sequence homology and activation mechanism (Rhee and Bae, 1997). The δ-type PLCs, δ1–δ4, are thought to be the primary forms expressed in mammals. Among these, PLCδ1 is expressed abundantly in most tissues (Suh et al., 1988; Lee et al., 1999) and has been studied most intensively. PLCδ1 is the most calcium-sensitive PLC (Allen et al., 1997) and is thought to be activated in response to calcium mobilization induced by β- or γ-type PLCs (Rhee and Bae, 1997; Kim et al., 1999). PLCδ1 activity is also regulated by sphingomyelin and spermine (Scarlata et al., 1996; Pawelczyk and Lowenstein, 1997). Other factors, such as transglutaminase II and the GTPase-activating protein for Rho, are also reported to play a role in PLCδ1 activation (Nakaoka et al., 1994; Homma and Emori, 1995). It has been suggested that PLCδ1 is involved in Alzheimer’s disease (Shimohama et al., 1991) and essential hypertension (Yagisawa et al., 1991; Kato et al., 1992); however, despite some progress in the structural understanding of PLCδ1 (Essen et al., 1996), its expression levels, regulation mechanisms, and biological and physiological functions are still poorly understood.

Mammalian skin is composed of at least three differentiated epithelial compartments: interfollicular epidermis (IFE), hair follicles and associated glands. It contains pluripotent stem cells that reside in the bulge and generate these compartments. The IFE is characterized by a polarized pattern of epithelial growth and differentiation, with a single basal layer of proliferating keratinocytes and multiple overlying differentiated layers. During differentiation, basal keratinocytes detach from the basement membrane, migrate to the suprabasal layers and are eventually shed. The hair follicle is a more complex structure composed of an outer root sheath (ORS), an inner root sheath (IRS) and a hair shaft, and it undergoes cycles of growth and regression. It has been reported that keratinocytes, the major component of IFE and hair follicles, possess a functionally active inositol lipid signaling system that plays an essential role in keratinocyte differentiation (Tang et al., 1988; Punnonen et al., 1993; Xie and Bikle, 1999).

In the present study, to elucidate the physiological roles of PLCδ1 we generated PLCδ1-deficient mice and found that they undergo progressive hair loss that is attributable to epidermal hyperplasia, occlusion of the hair canal, sebaceous gland hyperplasia and formation of abnormal cysts. These observations indicate that PLCδ1 is required for normal regulation of interfollicular epidermal keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, and for determination of skin stem cell fate in vivo.

Results

Generation of PLCδ1-deficient mice

To inactivate the PLCδ1 gene, we engineered a targeting vector in which the DNA encoding the catalytic domains of PLC was replaced with a neomycin-resistance cassette (Figure 1A). This vector yielded targeted recombination events in two independent embryonic stem (ES) cell clones. These ES cell clones were injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric germline heterozygous mice. Selective breeding of heterozygous knockout mice yielded homozygous knockout mice. Correct gene targeting was verified by Southern blot analysis (Figure 1B). Western blot analysis of testes (which normally express PLCδ1 abundantly) from knockout mice lacked the 85 kDa PLCδ1 protein (Figure 1C). Because our targeting strategy left the possibility that N-terminal fragments containing the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain could be expressed, we generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the N-terminal 60 amino acids of PLCδ1 and performed western blot analysis with this antibody to confirm that N-terminal fragments of PLCδ1 protein were not expressed. No such fragments were detected (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Targeted disruption of the PLCδ1 gene in mice. (A) Gene targeting strategy. Exons encoding the X and Y domains were replaced with a neomycin-resistance cassette (neo). gpt, xanthine/guanine phosphoribosyl transferase gene; DTA, diphtheria toxin A gene; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; X, X domain; Y, Y domain; D, DraI. (B) Southern blot analysis of mouse genomic DNA. DraI-digested genomic DNAs isolated from the tails of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/–) and PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice were hybridized with the 3′ probe. DraI digestion yields a 12.5 kb fragment for the wild-type allele and a 6.5 kb fragment for the mutant allele. (C) Western blotting of protein extracts from the testes of wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/–) and PLCδ1- deficient (–/–) mice. (D) Dorsal and (E) ventral views of 3.5-month-old wild-type (+/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice.

Heterozygous knockout mice of PLCδ1 appeared phenotypically normal and fertile, and intercrosses between heterozygous knockout mice produced pups with the expected Mendelian distribution (+/+:+/–:–/– = 45:74:39), indicating that disruption of PLCδ1 did not cause embryonic lethality. Homozygous knockout mice (PLCδ1-deficient mice) appeared fertile, although runting was evident. However, ∼90% of PLCδ1-deficient mice showed marked defects in ventral body hair, and ∼60% of them showed defects in dorsal body hair at 3.5 months of age (Figure 1D and E).

Hair canal occlusion and epidermal hyperplasia resulting from PLCδ1 disruption

Hair loss in PLCδ1-deficient mice was first observed 8 days after birth and was followed by progressive alopecia. Therefore, we analyzed morphological changes in hair follicles from wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining. The number of hair follicles was normal, but many hairs in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age failed to penetrate the epidermis and became zigzagged (Figure 2D), whereas hairs in wild-type mice penetrated the epidermis. Hair canals were occluded by differentiated keratinocytes including keratohyalin granules in mutant hair follicles (Figure 2D, arrow). In addition, the IFE of PLCδ1-deficient mice was thicker than that of wild-type mice (Figure 2A–D). The number of viable suprabasal cell layers was increased by one to two layers in comparison with that of the IFE of wild-type mice.

Fig. 2. Histological abnormalities in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age. HE staining of dorsal skin sections from (A and C) wild-type (+/+) and (B and D) PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice at 8 days of age. The arrow in (D) indicates hair canal occlusion by differentiated keratinocytes. The length of both heads and arrows (C and D) indicates the thickness of the epidermis except for the cornified layers. Analysis of keratinocyte proliferation in dorsal skin sections from (E) wild-type and (F) PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age by BrdU incorporation. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. (G) Number of BrdU-positive cells per field. Values represent the average number of BrdU-positive cells in 30 fields from three sections from different mice. The statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (p < 0.05). (H–J) Immunohistochemical detection of PLCδ1 in dorsal skin sections. Immunohistochemical staining of (H) wild-type and (I) PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age with a polyclonal anti-PLCδ1 antibody. (J) Immunohistochemical staining with antigen-absorbed antibody on wild-type skin was also carried out. Bars: (A and B), shown in (A), 100 µm; (C and D), shown in (C), 50 µm; (E and F), shown in (E), 50 µm; (H–J), shown in (H), 50 µm.

Because interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia was observed, we investigated the proliferative activity of epidermal keratinocytes by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation. The number of interfollicular and upper-follicular cells that incorporated BrdU was ∼8 times greater in PLCδ1-deficient mice than in wild-type mice (30 ± 3.8 and 3.6 ± 1.9 cells/field, respectively) (Figure 2E–G). These data indicate that PLCδ1 plays a critical role in the regulation of keratinocyte proliferation and that disruption of this gene results in interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia.

To further understand the physiological role of PLCδ1 in skin, we determined the localization of PLCδ1 in wild-type mice. In wild-type skin, PLCδ1 was localized predominantly in the upper region of the hair follicle ORS and in all of the IFE except the cornified layers (Figure 2H). PLCδ1 immunoreactivity was not detected in skin from PLCδ1-deficient mice (Figure 2I) or in skin from wild-type mice stained with antigen-absorbed PLCδ1 antibody (Figure 2J). These expression patterns of PLCδ1 in skin imply that it plays an important role in regulating keratinocyte growth and differentiation in IFE and upper ORS.

Abnormal differentiation of epidermis and hair follicles in PLCδ1-deficient mice

Because abnormal epidermal and hair follicle morphologies were observed in skin from PLCδ1-deficient mice, we investigated how the absence of PLCδ1 influences differentiation of keratinocytes in these structures. To do this, we examined the expression of molecular markers in skin from wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age by immunofluorescence. Cytokeratin 1 (K1) and loricrin, markers of terminal differentiation in normal IFE, were also detected in the upper region of mutant hair follicle ORS (Figure 3B and H, arrows), where occlusion of hair canals was observed on HE-stained sections, whereas these markers were detected only in IFE in wild-type mice (Figure 3A and G). These observations suggest that the upper region of mutant hair follicle ORS differentiated in a manner similar to that of normal IFE. In addition, cytokeratin 6 (K6), a hair follicle ORS marker that is normally absent from keratinocytes in the IFE (Figure 3E), was also expressed in mutant IFE (Figure 3F). Aberrant expression of K6 was reported to be associated with epidermal hyperproliferation (Porter et al., 1998), and PLCδ1-deficient mice displayed this phenomenon. Expression of cytokeratin 5 (K5), a marker of interfollicular basal keratinocytes and the hair follicle ORS, was slightly enhanced in PLCδ1-deficient mice in comparison with wild-type mice (Figure 3C and D). Thus, differentiation of keratinocytes in the IFE and hair follicle was disturbed in the absence of PLCδ1.

Fig. 3. Abnormal differentiation of keratinocytes in the epidermis and hair follicles of PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age. Green corresponds to antibody staining, and red corresponds to PI (BO-PRO-3) staining. Dorsal skin sections from wild-type (left, +/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (right, –/–) mice at 8 days of age were stained with antibody against (A and B) cytokeratin 1 (K1), (C and D) cytokeratin 5 (K5), (E and F) cytokeratin 6 (K6) and (G and H) loricrin (lor). Arrows indicate aberrant K1 (B) and loricrin (H) expression in the upper portion of mutant hair follicles. Bars: (A–H), shown in (A), 100 µm.

Characterization of PLCδ1-deficient primary keratinocytes

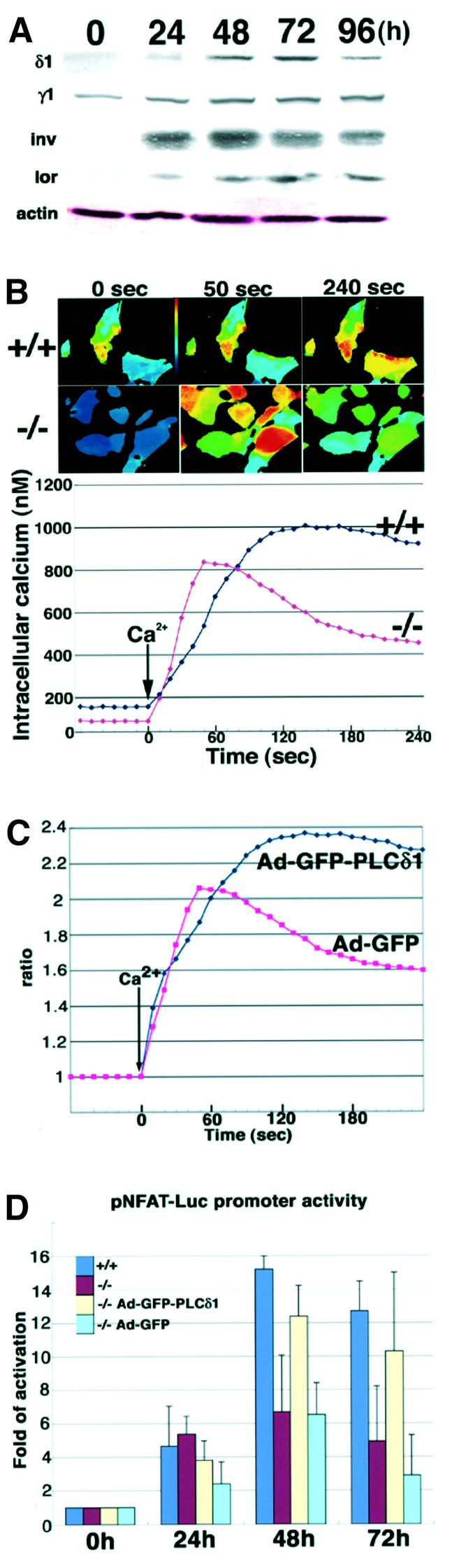

Keratinocytes possess a functionally active inositol lipid signaling system that plays an essential role in their differentiation. PLCγ1 is expressed abundantly in keratinocytes and regulates this process (Punnonen et al., 1993; Xie and Bikle, 1999). Therefore, we examined expression of PLCγ1, PLCδ1 and the terminal differentiation markers involucrin and loricrin in primary keratinocytes. Expression of PLCδ1 protein was increased >10-fold after calcium treatment, whereas PLCγ1 protein expression was increased only slightly (Figure 4A). However, there were no apparent differences in levels of involucrin and loricrin between wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes (data not shown).

Fig. 4. Changes in calcium signaling in PLCδ1-deficient primary cells. (A) PLCδ1 and PLC γ1 contents during calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation. Primary keratinocytes were treated with 1 mM CaCl2 for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, and 15 µg of total protein were subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot analysis was performed. Actin was used as the loading control. δ1, PLCδ1; γ1, PLCγ1; inv, involucrin; lor, loricrin. (B) Keratinocytes from wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice differentiated for 72 h were stimulated with 1.6 mM CaCl2. Fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) imagings of wild-type (+/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) keratinocytes at the indicated times are shown in the upper panels. Time courses of [Ca2+]i mobilization in wild-type (+/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) keratinocytes are shown in the lower panel. Data were collected in independent experiments (n = 40). (C) Adenoviral infection of PLCδ1 or GFP was performed in PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes. PLCδ1- and GFP-infected keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice differentiated for 72 h were stimulated with 1.6 mM CaCl2. Time courses of [Ca2+]i mobilization in PLCδ1-infected (Ad-GFP-PLCδ1) and GFP-infected (Ad-GFP) keratinocytes are shown. Values were calculated by comparison with the 340/380 ratio of cells without Ca2+stimulation. (D) The change in NFAT transcriptional activity in keratinocytes. Adenoviral infection of PLCδ1 or GFP was performed in PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes. Luciferase activity was measured 76 h after transfection of pNFAT-Luc in wild-type (+/+), PLCδ1-deficient (–/–), PLCδ1-infected PLCδ1-deficient (–/– Ad-GFP-PLCδ1) and GFP-infected PLCδ1-deficient(–/– Ad-GFP) cells untreated or treated with high Ca2+(1.0 mM) for the last 24, 48 and 72 h of the experiment (0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h). Values were calculated by comparison with the activity of cells untreated with high Ca2+ (0 h). Statistical significance between +/+ and –/– at 48 and 72 h was determined by Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

Because PLCδ1 is the most calcium-sensitive PLC, it is presumed to be activated by calcium mobilization induced by β- and γ-type PLCs, and it boosts and sustains calcium elevation (Allen et al., 1997; Rhee and Bae, 1997; Kim et al., 1999). Thus, it may play a specific role in calcium mobilization which cannot be compensated by other PLCs such as PLCγ1. To test this hypothesis, we compared the change in the intracellular calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i, in response to the extracellular calcium concentration, [Ca2+]o, in primary keratinocytes from wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice. In this case we used keratinocytes differentiated for 72 h because PLCδ1 is expressed most abundantly (Figure 4A). The basal [Ca2+]i of keratinocytes from wild-type mice (158 nM) was slightly higher than that of keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice (93 nM). In keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice, [Ca2+]i peaked (834 nM) 50 s after calcium stimulation, whereas that of keratinocytes from wild-type mice peaked (1004 nM) at 140 s. At that time point, the [Ca2+]i of keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice had already decreased to 597 nM. At 240 s, the [Ca2+]i of keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice had decreased to 453 nM, although that of keratinocytes from wild-type mice remained high (917 nM). Thus, elevation of [Ca2+]i in response to [Ca2+]o was more transient in keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice than in those from wild-type mice (Figure 4B). However, when these experiments were carried out with non-differentiated keratinocytes in which PLCδ1 is expressed at very low levels, the mobilization of [Ca2+]i in response to [Ca2+]o was the same in keratinocytes from both wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice (data not shown). These data suggest that PLCδ1 is important for sustaining high [Ca2+]i. In fact, adenoviral infection of the PLCδ1 gene in PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes rescued this defect (Figure 4C). Calcium-dependent nuclear translocation of calcineurin β, one event subsequent to calcium elevation, was also lower in PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes (22.4% of cells, n = 514) than in wild-type keratinocytes (35.7% of cells, n = 487). Because sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i is required for activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and because calcineurin regulates NFAT activity (Dolmetsch et al., 1997), we next examined NFAT activity using a luciferase assay. The transcriptional activity of NFAT was increased 15.2-fold at 48 h and 12.7-fold at 72 h after exposure to high [Ca2+]o in wild-type cells, whereas this elevation of transcriptional activity was lower in PLCδ1-deficient cells (6.7-fold at 48 h and 4.9-fold at 72 h) (Figure 4D). Furthermore, we confirmed that adenoviral infection of PLCδ1 into PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes recovered the impaired NFAT promoter activity of PLCδ1-deficient keratinocytes (Figure 4D). Expression of terminal differentiation markers was not altered by infection of PLCδ1 (data not shown). These results suggest that suppression of NFAT activity is not caused by altered differentiation, but rather is a primary consequence of loss of PLCδ1. Thus, calcium mobilization and activation of calcineurin and NFAT were impaired in PLCδ1-deficient primary keratinocytes.

Change in downstream effectors of PLC in skin

We then examined activation of PKC, the downstream effector of PLC in skin. PKC activity is controlled by phosphorylation of conserved sites (Keranen et al., 1995). We performed immunohistochemical staining of skin sections with an antibody that discriminates between phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated PKCs. Phosphorylated PKCs were clearly detected in the suprabasal layers of the IFE and the upper regions of hair follicles in the skin of wild-type mice (Figure 5A), whereas they were barely visible in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice (Figure 5B). We also analyzed the levels of phosphorylated PKCs in epidermal extracts. Levels of phosphorylated PKCs were markedly decreased in PLCδ1-deficient epidermis extracts (Figure 5C). We then examined levels of some PKC isozymes (α, δ, η and ζ). To our surprise, levels of PKC isozymes were also decreased and possible degradation products of PKC isozymes were detected within the lower molecular weight range (Figure 5C). These degradation products were not observed in the heart and testis, in which PLCδ1 is also abundantly expressed, suggesting that PLCδ1 plays an important role in the stability and degradation of PKCs in the suprabasal layers of the IFE and the upper region of the hair follicles, although other factors may contribute to the instability of PKC in skin. Because we observed marked changes in levels of PKC isozymes between wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient epidermis, we further examined activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), which has been reported to be regulated by PKC and calcium signaling (Hughes et al., 1998; Jang et al., 2001; Kanke et al., 2001; Vancurova et al., 2001). NF-κB plays an important role in balancing growth and differentiation in the IFE and hair follicles, and inhibition of NF-κB signaling in these regions leads to epidermal hyperplasia (van Hogerlinden et al., 1999; Kaufman and Fuchs, 2000; Schmidt-Ullrich et al., 2001) similar to that observed in PLCδ1-deficient mice. NF-κB activity is regulated primarily by translocation from the cytoplasm, where it is bound to the inhibitor of κB (IκB), to the nucleus, where it induces expression of target genes (Verma et al., 1995; Beg and Baltimore, 1996). Therefore, we investigated the intracellular localization of NF-κB with an antibody directed against the p50 subunit. NF-κB was present predominantly in nuclei in wild-type IFE, whereas nuclear localization of NF-κB was not prominent in IFE from PLCδ1-deficient mice (Figure 5D and E). In addition, we ascertained whether suppression of NF-κB activity was an effect of decreased PKC signaling. To examine this, we investigated the localization of NF-κB after treatment with PMA, a PKC activator, in the skin of wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice. If suppression of NF-κB activity was caused by insufficient PKC activation, PKC activation by PMA should rescue impaired NF-κB activity in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice. In fact, strong nuclear localization of NF-κB was observed in the skin of both wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice (Figure 5F and G). These data indicate that PKC-mediated NF-κB activation plays an important role downstream of PLCδ1 in skin.

Fig. 5. Downstream effectors of PLCδ1. Green corresponds to antibody staining (A, B, D, E), and red corresponds to PI (BO-PRO-3) staining (A and B). Immunohistochemical detection of active PKC in dorsal skin sections from (A) wild-type (+/+) and (B) PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice at 8 days of age. (C) Protein levels of phosphorylated PKCs and PKC isozymes. Western blot analysis of protein extracts from the epidermis of wild-type (+/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice was carried out. Arrowheads indicate the molecular size of full-length phosphorylated PKCs and PKC isozymes. Arrows indicate possible degraded PKC isozymes. Actin was used as the loading control. Localization of NF-κB (p50) in dorsal skin sections from (D) wild-type (+/+) and (E) PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice at 8 days of age. Arrows in (D) indicate nuclear localization of p50 in normal skin. Back skins of (F) wild-type (+/+) and (G) PLCδ1-deficient mice (–/–) were treated with 1 µg/ml PMA in acetone for 2 h and harvested. Immuno histochemical detection of NF-κB p65 subunit was performed on frozen sections. Bars: (A and B), shown in (A), 50 µm; (D and E), shown in (D), 50 µm; (F and G), shown in (F), 50 µm.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia and cyst formation in PLCδ1-deficient mice

Hair follicle morphology was severely disrupted in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice at 15 days of age, although the interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia was less remarkable than that at 8 days of age (Figure 6A and B). Sebaceous glands were enlarged, and the number of sebocytes was greatly increased (Figure 6C and D). In addition, many hair follicle-derived cysts were identified within the dermis of PLCδ1-deficient skin (Figure 6B). These cysts were filled with horny cells and were surrounded by multilayered epithelium containing cells that resembled the wild-type epidermal granular layers (Figure 6E and F, arrows). Such cysts were never observed in skin from wild-type mice (Figure 6A). At 25 days of age, when hair follicles in wild-type skin enter a new anagen phase and grow down into the subcutis (Figure 6G), the cysts enlarged somewhat and the hair follicles showed more severe disorganization in PLCδ1-deficient mice (Figure 6H).

Fig. 6. Abnormal cyst formation and sebaceous gland hyperplasia in PLCδ1-deficient mice. HE staining of dorsal skin sections from (A, C and E) wild-type (+/+) and (B, D and F) PLCδ1-deficient (–/–) mice at 15 days of age. Arrows in (C) and (D) indicate sebaceous glands. Arrow in (E) indicates granular layers of wild-type IFE. Arrow in (F) indicates cells of abnormal cysts, which resemble those of the granular layers of wild-type IFE. HE staining of dorsal skin sections from (G) wild-type and (H) PLCδ1-deficient mice at 25 days of age. Comparison of ultrastructure of (I) normal epidermis and (J) hair follicle-derived cysts. Arrows in (I) and (J) indicate desmosomes. Arrowheads in (I) and (J) indicate keratohyalin granules. Bars: (A, B, G and H), shown in (A), 100 µm; (C, D and F), shown in (C), 50 µm; (E), 50 µm; (I and J), shown in (I), 2 µm.

Similarity of cysts to IFE

We also performed ultrastructural analysis of normal IFE and hair follicle-derived cysts (Figure 6I and J). The cysts were surrounded by several viable cell layers containing prominent desmosomes (Figure 6J, arrows). These layers corresponded to the spinous layers of normal IFE. Further within the inner layer, there was a layer containing keratohyalin granules (Figure 6J, arrowheads), which corresponded to the granular layer of normal IFE. In the innermost layers, electron-dense squames that were equivalent to the cornified layers of normal IFE were identified.

Next, we examined the expression of molecular markers in the cysts observed in PLCδ1-deficient mice at 15 days of age. Keratinocytes in the central layers of the cysts expressed K6 (Figure 7E and F). K5, K1 and loricrin were detected in the peripheral cell layer, all viable cell layers except the most peripheral and the innermost cell layer of the cysts, respectively. Thus, moving inward from the peripheral cell layer in mutant hair follicle-derived cysts, an expression pattern, first K5, then K1 and finally loricrin, was observed (Figure 7B, D, H and N). Such an expression pattern is usually present only in the basal to cornified layers of wild-type IFE (Figure 7A, C, G and M), indicating that the cysts undergo a program of terminal differentiation similar to that of IFE. Thus, the cysts detected in PLCδ1-deficient mice showed remarkable similarities to the IFE of wild-type mice at the ultrastructural and molecular marker levels. Furthermore, the expressions of AE13 and AE15, pan-hair keratin marker and IRS marker, respectively, were not detected in the cysts (Figure 7J and L), whereas expressions of these markers were detected in hair follicles of wild-type mice (Figure 7I and K). These observations indicate that, in the absence of PLCδ1, cells of hair follicle-derived cysts have lost their follicular characteristics and exhibit interfollicular epidermal differentiation. Thus, these data strongly suggest that PLCδ1 is involved in lineage determination of keratinocytes in IFE and hair follicles.

Fig. 7. Similarities in expression of molecular markers between cysts and IFE. In (A–H), green corresponds to antibody staining, and red corresponds to PI (BO-PRO-3) staining. Dorsal skin sections from wild-type (left, +/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (right, –/–) mice at 15 days of age were stained with antibody against (A and B) cytokeratin 1 (K1), (C and D) cytokeratin 5 (K5), (E and F) cytokeratin 6 (K6) and (G and H) loricrin (lor). Arrows indicate aberrant K1 (B) and loricrin (H) expression in hair follicle-derived cysts. In (I–L), green corresponds to antibody staining, and red corresponds to K5 staining. Dorsal skin sections from wild-type (left, +/+) and PLCδ1-deficient (right, –/–) mice at 15 days of age were stained with antibody against (I and J) AE13 and (K and L) AE15. (M and N) The similarity between hair follicle-derived cyst in (M) PLCδ1-deficient mice and (N) normal epidermis. Bars: (A–H), shown in (A), 100 µm; (I–L), shown in (I), 50 µm.

Spontaneous skin tumors observed inPLCδ1-deficient mice

PLCδ1-deficient mice developed spontaneous skin tumors in ventral skin. The incidence of tumors in PLCδ1-deficient mice was ∼20% (18/88) of mice over 3 months old. Such tumors were never observed in wild-type mice. Next, we characterized these tumors at the histological level. They arose from underneath the IFE, and large cysts and many sebocyte-like cells surrounded by basaloid keratinocytes were observed in them (Figure 8C and D). The sebocyte-like cells were positively stained with Oil Red O, a histochemical dye specific for lipid-containing cells (Figure 8E and F). K1 was also expressed in the sebocyte-like cells in addition to the inner layer of large cysts (Figure 8G and H). K5 was expressed in peripheral cell layers surrounding the sebocyte-like cells and in large cysts (Figure 8I and J). Thus, these tumors had the characteristics of both IFE and the sebaceous glands. Since it has been reported that impaired lineage commitment of skin stem cells induces development of tumors that have the properties of sebaceous glands in the skin (Niemann et al., 2002), these results strongly support the idea that PLCδ1 is involved in skin stem cell lineage determination.

Fig. 8. Development of spontaneous skin tumors in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice. (A and B) Skin tumors developed in PLCδ1-deficient mice. Arrows indicate tumors. (C and D) HE staining of tumor sections from PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age. Arrows in (C) indicate large cysts and the arrow in (D) indicates sebocyte-like cells observed in these tumors. Sections were stained with (E and F) Oil Red O, (G and H) cytokeratin 1 and (I and J) cytokeratin 5. (K) Summary of disturbed lineage commitment in PLCδ1-deficient mice. Bars: (C), 200 µm; (D and H), shown in (D), 25 µm; (E),100 µm; (F and J), shown in (F), 50 µm; (G and I), shown in (G), 50 µm.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia, which reflects an increase in the number of differentiated cell layers, is observed in PLCδ1-deficient mice at 8 days of age. The IFE is maintained by a finely tuned balance between keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation that results in a multilayer structure consisting of basal, spinous, granular and cornified layers. Therefore, interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia of PLCδ1-deficient mice suggests that PLCδ1 is required for regulation of balance between keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation.

PKC is one downstream effector of PLC activation. At least six PKC isoenzymes (PKC-α, δ, ε, η, ζ and µ) are known to be expressed in keratinocytes, and they are thought to be central regulators of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation (Dlugosz and Yuspa, 1993). In the suprabasal layers of the IFE and the upper region of the hair follicle ORS, where PLCδ1 is expressed at fairly high levels in wild-type mice, phosphorylated forms of PKCs were barely detected in PLCδ1-deficient mice. This was caused by enhanced PKC degradation in PLCδ1-deficient epidermis, although the mechanism is still unclear. This degradation was not observed in testis and heart, where PLCδ1 is abundantly expressed, suggesting that this enhanced PKC degradation is the skin-specific event. Thus, insufficient PKC activity may be the cause of the epidermal hyperplasia and abnormal morphologies of hair follicles in PLCδ1-deficent skin. Furthermore, translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, which occurs during keratinocyte differentiation, was also inhibited in the IFE of PLCδ1-deficient mice. Because it has been reported that NF-κB plays a role in balancing keratinocyte growth and differentiation (Seitz et al., 1998), these skin abnormalities of PLCδ1-deficient mice may be attributable to impaired NF-κB signaling. In addition, this impaired NF-κB activity can be rescued by treatment with the PKC activator PMA, which strongly stimulates PKC and induces sufficient PKC activity to result in the activation of NF-κB, even though the protein levels of PKC are decreased in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice.

We also found that expression of PLCδ1 is induced transiently after calcium treatment and plays critical roles in calcium mobilization and activation of its downstream effectors, calcineurin and NFAT, in primary cells. After calcium treatment, intracellular PLC activation occurs through a calcium-sensing receptor (Hebert and Brown, 1995; Chattopadhyay et al., 1996) or by an undefined mechanism (Jaken and Yuspa, 1988). It was reported recently that PLCγ1 is critical for mobilization of intracellular calcium in response to calcium treatment (Xie and Bikle, 1999). Despite the presence of PLCγ1, defective calcium mobilization was observed in PLCδ1-deficient mice. One possible explanation is that PLCγ1 is first activated by calcium treatment and triggers IP3 production and intracellular calcium elevation. This transient calcium elevation by PLCγ1 stimulates PLCδ1, the most calcium-sensitive PLC, which prolongs the intracellular calcium elevation and the activation of its downstream effectors. In fact, in keratinocytes from PLCδ1-deficient mice, elevation of [Ca2+]i in response to [Ca2+]o was more transient, and activation of NFAT, which is activated by sustained elevation of calcium, was inhibited. A direct influx of extracellular calcium through non-specific cation channels and cGMP-gated channels has been reported in keratinocytes (Galietta et al., 1991; Mauro et al., 1993; Oda et al., 1997), and elevation of calcium levels by this influx may also activate PLCδ1. It has been reported that calcineurin and NFAT activities were induced during calcium-induced differentiation of keratinocytes, and suppression of calcineurin activity by cyclosporin A (CsA) results in impaired expression of terminal differentiation markers (Santini et al., 2001). However, expression of terminal differentiation markers induced by exposure to high calcium was not altered in primary keratinocytes from wild-type and PLCδ1-deficient mice. One possible explanation is that suppression of NFAT activity caused by the loss of PLCδ1 was insufficient to interfere with induction of terminal differentiation markers. In fact, a low concentration of CsA failed to suppress expression of terminal differentiation markers, although NFAT promoter activity was suppressed approximately one-third at this CsA concentration (Santini et al., 2001).

In addition, we show that sebaceous gland hyperplasia and the formation of cysts, which show remarkable similarities to IFE and lose the characteristics of hair follicle, occur in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice. The epidermis is maintained throughout life by pluripotent stem cells producing, via daughter cells of high differentiation probability, IFE, hair follicles and sebaceous glands (Taylor et al., 2000; Watt and Hogan, 2000; Oshima et al., 2001). Therefore, sebaceous gland hyperplasia and the formation of such cysts reflect suppression of the hair follicle differentiation pathway and promotion of IFE and sebaceous gland differentiation. Furthermore, spontaneous skin tumor development was observed in PLCδ1-deficient mice. Single oncogenic mutations in keratinocytes that are undergoing terminal differentiation will be innocuous, as the cells are rapidly shed from the epidermis. In contrast, stem cells have the potential to accumulate multiple mutations and undergo neoplastic conversion (Jensen et al., 1999; Taipale and Beachy, 2001). Therefore, the cells that generate tumors in the skin of PLCδ1-deficient mice are likely to be stem cells. In addition, these tumors have characters of sebocytes and IFE keratinocytes, indicating that in the absence of PLCδ1, stem cells preferentially differentiate into sebocytes and IFE. Thus, these changes indicate that PLCδ1 is required for lineage commitment of skin stem cells (Figure 8K).

Taken together, these results show that PLCδ1 regulates skin stem cell lineage commitment and is involved in interfollicular epidermal keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation in vivo. However, in comparison with the dramatic change in hair follicle morphology, that of IFE was comparatively small although interfollicular epidermal hyperplasia and abnormal K6 expression were observed. Thus, the phenotype of PLCδ1-deficient mice appears to reflect the disturbance of skin stem cell lineage commitment more. Similar cysts are observed upon overproduction of Zipro1, a zinc-finger transcription factor (Yang et al., 1999), after disruption of RXRα (Li et al., 2000) or the vitamin D receptor (Li et al., 1997) and in mice with mutation of the Hairless (h) gene, which encodes a putative transcription factor (Panteleyev et al., 1998). In addition, inhibition of Wnt signaling by ablation of the β-catenin gene (Huelsken et al., 2001) or by expressing the Lef1 transgene lacking the β-catenin binding site (Merrill et al., 2001; Niemann et al., 2002) results in production of cysts. However, the apparent molecular relationship between these genes and PLCδ1 is unknown. In PLCδ1-deficient mice, hair loss was first observed 8 days after birth owing to occlusion of the hair, and such a phenotype was never observed at this stage in these mice. Thus, the phenotype of these mice was different from that of PLCδ1-deficient mice in some points. This suggests that PLCδ1 may control skin stem cell lineage commitment via another novel pathway. Two major downstream effectors of PLCδ1, which also have broad signaling functions in cells, are PKC activation and calcium mobilization. Since calcium influx and activation of PKC are altered in the skin of mutant mice, it is possible that PLCδ1 may control the lineage commitment of skin stem cells by altering these effectors, thereby modifying many downstream targets.

We show here for the first time that PLCδ1 is required for the determination of skin stem cell lineage. Clarifying the mechanisms underlying the determination of skin stem cell fate may permit engineering of the epidermis to produce more hair follicles as a treatment for balding or the development of therapies for excess sebum production in teenagers, for example. Thus, understanding the way that PLCδ1 regulates skin stem cell lineage commitment is very important. However, further investigation is needed to clarify this, and it is a subject for the future.

Materials and methods

Generation of PLCδ1-deficient mice

Phage clones containing the exons that encode the X and Y domains of PLCδ1 were isolated from a FIXII mouse genomic library (strain 129SV/J). In the targeting vector, the 5.7 kb DNA fragment encompassing the X and Y domains of the PLCδ1 coding sequence was deleted and replaced with a neomycin-resistance cassette. The NotI-linearized targeting vector was electroporated into 129/Ola embryonic stem cells (ES cells). Two independent, heterozygous ES cell clones were used to generate chimeric mice by blastocyst injection, and mutant animals were bred on a mixed 129/Ola × C57BL/6J background. Genotyping was carried out by Southern blot and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. For Southern blot analysis, genomic DNA was digested with DraI and hybridized with a 3′ probe. The 3′ probe corresponded to a 0.2 kb HindIII–PstI DNA fragment isolated from the PLCδ1 genomic clone. Primers for PCR analysis were 5′-CAAGGAGGTGAAGGACTTCCTG-3′, 5′-CTGGGT CAGCATCCTGTAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CCTGTGCTCTAGTAGCTTTA CG-3′.

Western blot analysis

Testes from wild-type, heterozygote and homozygote knockout mice were flash frozen, pulverized in liquid nitrogen and incubated for 10 min in SDS–PAGE sample buffer at 95°C. For primary keratinocytes, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed directly with SDS–PAGE sample buffer. For the analysis of phosphorylated PKCs, epidermis was separated from skin and the separated epidermis was washed with PBS, placed into RIPA buffer, homogenized, sonicated and centrifuged for 15 min at 10 000 g to remove insoluble debris. SDS sample buffer was then added and incubated for 10 min at 95°C. The lysates were resolved by SDS–PAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies.

Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry

All skin biopsies were matched for age, sex and body site. For HE staining, skin samples were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Immunofluorescence was performed on 10 µm thick cryosections and on keratinocytes. Cryosections were incubated with primary antibodies to cytokeratin 1, cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 6, loricrin (Babco), NF-κBp50, NF-κBp65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), AE13, AE15 (a gift from T.T.Sun, New York University Medical School) or phospho-PKC (pan) (Cell Signaling), which recognizes phosphorylated PKCα, βI, βII, δ, ε and η after fixation in acetone. Sections were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes). Keratinocytes were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and incubated with anti-calcineurin β antibody (Upstate Biotechnology) and then Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Molecular Probes). Counterstaining was performed with BO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes). Stained sections and cells were examined and photographed with a confocal microscope (Radiance 2000; Bio-Rad). For PLCδ1 immunohistochemistry, 5 µm cryosections of skin were fixed in acetone at –80°C for 5 min and incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-PLCδ1 antibody followed by the procedure described in the technical bulletin of the tyramide signal amplification (TSA) immunodetection kit (NEN).

BrdU labeling

BrdU labeling was performed with a 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine labeling and detection kit II (Roche) by intraperitoneal injection of BrdU into mice according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Cell culture

Primary murine keratinocytes were isolated from newborn wild-type or PLCδ1-deficient mice (<1 day old) by overnight trypsin flotation. Isolated keratinocytes were plated at 6 × 106 cells per 60 mm dish in serum-free keratinocyte growth medium (KGM) (Clonetics) supplemented with 0.05 mM Ca2+. To induce differentiation, the cells were grown to ∼50% confluence, treated with culture medium supplemented with 1 mM Ca2+ and cultured for various times before harvest.

Generation of adenoviruses

Recombinant adenoviruses were generated using the AdEasy System as described previously (He et al., 1998).

Intracellular calcium measurement

Primary murine keratinocytes cultured for various times after exposure to high calcium (1 mM) were loaded with 7.5 µM Fura-2 AM and 0.05 mM calcium in buffer A (20 mM HEPES, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, 1 mg/ml glucose). Cells were then exposed to 1.6 mM calcium. The fluorescence (ratio of F340 nm to F380 nm) from single cells was recorded using an image analyzer. The signals from 10 single cells for each preparation were recorded and an average profile of 40 single cells from four preparations was calculated. Each sample was calibrated by the addition of ionomycin (20 µM final concentration) (Fmax) followed by 25 mM EGTA–Tris–HCl pH 8.3 (Fmin). Intracellular calcium concentration was calculated from the following formula:

[Ca2+] = KdQ (R – Rmin)/(Rmax – R)

where R = F340 nm/F380 nm, Q = Fmin/Fmax at 380 nm and Kd for Fura-2 for Ca2+ is 224 nM.

Luciferase assay

For the luciferase assay, primary keratinocytes were seeded in 24-well plates. At ∼70–80% confluence, cells were transfected with pNFAT-Luc plasmid (Stratagene). Transfection was performed using FuGENE6 reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Luciferase activity was measured 76 h after transfection in untreated cells or cells treated with high Ca2+ (1.0 mM) for the final 24, 48 or 72 h of the experiment. Preparation of cell lysates and measurement of luciferase activity were performed with a Luciferase Assay Kit (Stratagene) and a Fusion™α (Packard) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples from triplicate wells were examined and the experiment was repeated twice. Differences were analyzed for statistical significance using Student’s t-test.

Ultrastructural analysis

Skin tissues were processed for conventional transmission electron microscopy by fixation in 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer followed by 2% osmium tetroxide in water for 3 h on ice. Ultrathin sections (70–80 nm) on copper grids were treated with 2% uranyl acetate and examined with a JEOL JEM-200EX electron microscope at 100 kV.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank P.G.Suh, N.Huh, K.Chida and K.Fujiwara for materials, and Y.Fukamizu for advice about the animal experiments.

References

- Allen V., Swigart,P., Cheung,R., Cockcroft,S. and Katan,M. (1997) Regulation of inositol lipid-specific phospholipase cδ by changes in Ca2+ ion concentrations. Biochem. J., 327, 545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A.A. and Baltimore,D. (1996) An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science, 274, 782–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. and Irvine,R.F. (1984) Inositol trisphosphate, a novel second messenger in cellular signal transduction. Nature, 312, 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay N., Mithal,A. and Brown,E.M. (1996) The calcium-sensing receptor: a window into the physiology and pathophysiology of mineral ion metabolism. Endocr. Rev., 17, 289–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch R.E., Lewis,R.S., Goodnow,C.C. and Healy,J.I. (1997) Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature, 386, 855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosz A.A. and Yuspa,S.H. (1993) Coordinate changes in gene expression which mark the spinous to granular cell transition in epidermis are regulated by protein kinase C. J. Cell Biol., 120, 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen L.O., Perisic,O., Cheung,R., Katan,M. and Williams,R.L. (1996) Crystal structure of a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase Cδ. Nature, 380, 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galietta L.J., Barone,V., De Luca,M. and Romeo,G. (1991) Characterization of chloride and cation channels in cultured human keratinocytes. Pflugers Arch., 418, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T.C., Zhou,S., da Costa,L.T., Yu,J., Kinzler,K.W. and Vogelstein,B. (1998) A simplified system for generating recombinant adenoviruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 2509–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert S.C. and Brown,E.M. (1995) The extracellular calcium receptor. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 7, 484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma Y. and Emori,Y. (1995) A dual functional signal mediator showing RhoGAP and phospholipase C-δ stimulating activities. EMBO J., 14, 286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsken J., Vogel,R., Erdmann,B., Cotsarelis,G. and Birchmeier,W. (2001) Beta-catenin controls hair follicle morphogenesis and stem cell differentiation in the skin. Cell, 105, 533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K., Antonsson,A. and Grundstrom,T. (1998) Calmodulin dependence of NFκB activation. FEBS Lett., 441, 132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaken S. and Yuspa,S.H. (1988) Early signals for keratinocyte differentiation: role of Ca2+-mediated inositol lipid metabolism in normal and neoplastic epidermal cells. Carcinogenesis, 9, 1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang M.K., Goo,Y.H., Sohn,Y.C., Kim,Y.S., Lee,S.K., Kang,H., Cheong,J. and Lee,J.W. (2001) Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV stimulates nuclear factor-κB transactivation via phosphorylation of the p65 subunit. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 20005–20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen U.B., Lowell,S. and Watt,F.M. (1999) The spatial relationship between stem cells and their progeny in the basal layer of human epidermis: a new view based on whole-mount labelling and lineage analysis. Development, 126, 2409–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanke T., Macfarlane,S.R., Seatter,M.J., Davenport,E., Paul,A., McKenzie,R.C. and Plevin,R. (2001) Proteinase-activated receptor-2-mediated activation of stress-activated protein kinases and inhibitory κB kinases in NCTC 2544 keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 31657–31666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H., Shibasaki,F. and Takenawa,T. (1992). Activation of phospholipase Cδ in the aortas of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 6483–6487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman C.K. and Fuchs,E. (2000) It’s got you covered. NF-κB in the epidermis. J. Cell Biol., 149, 999–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keranen L.M., Dutil,E.M. and Newton,A.C. (1995). Protein kinase C is regulated in vivo by three functionally distinct phosphorylations. Curr. Biol., 5, 1394–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Park,T.J., Lee,Y.H., Baek,K.J., Suh,P.G., Ryu,S.H. and Kim,K.T. (1999) Phospholipase C-δ1 is activated by capacitative calcium entry that follows phospholipase C-β activation upon bradykinin stimulation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 26127–26134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.K., Kim,J.K., Seo,M.S., Cha,J.H., Lee,K.J., Rha,H.K., Min,D.S., Jo,Y.H. and Lee,K.H. (1999) Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a mouse phospholipase C-δ1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 261, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Indra,A.K., Warot,X., Brocard,J., Messaddeq,N., Kato,S., Metzger,D. and Chambon,P. (2000) Skin abnormalities generated by temporally controlled RXRα mutations in mouse epidermis. Nature, 407, 633–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.C., Pirro,A.E., Amling,M., Delling,G., Baron,R., Bronson,R. and Demay,M.B. (1997) Targeted ablation of the vitamin D receptor: an animal model of vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 9831–9835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro T.M., Isseroff,R.R., Lasarow,R. and Pappone,P.A. (1993) Ion channels are linked to differentiation in keratinocytes. J. Membr. Biol., 132, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill B.J., Gat,U., DasGupta,R. and Fuchs,E. (2001) Tcf3 and Lef1 regulate lineage differentiation of multipotent stem cells in skin. Genes Dev., 15, 1688–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaoka H., Perez,D.M., Baek,K.J., Das,T., Husain,A., Misono,K., Im,M.J. and Graham,R.M. (1994) Gh: a GTP-binding protein with transglutaminase activity and receptor signaling function. Science, 264, 1593–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann C., Owens,D.M., Hulsken,J., Birchmeier,W. and Watt,F.M. (2002) Expression of DeltaNLef1 in mouse epidermis results in differentiation of hair follicles into squamous epidermal cysts and formation of skin tumours. Development, 129, 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. (1988) The molecular heterogeneity of protein kinase C and its implications for cellular regulation. Nature, 334, 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y., Timpe,L.C., McKenzie,R.C., Sauder,D.N., Largman,C. and Mauro,T. (1997) Alternatively spliced forms of the cGMP-gated channel in human keratinocytes. FEBS Lett., 414, 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H., Rochat,A., Kedzia,C., Kobayashi,K. and Barrandon,Y. (2001) Morphogenesis and renewal of hair follicles from adult multipotent stem cells. Cell, 104, 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panteleyev A.A., van der Veen,C., Rosenbach,T., Muller-Rover,S., Sokolov,V.E. and Paus,R. (1998) Towards defining the pathogenesis of the hairless phenotype. J. Invest. Dermatol., 110, 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk T. and Lowenstein,J.M. (1997) The effect of different molecular species of sphingomyelin on phospholipase Cδ1 activity. Biochimie, 79, 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter R.M., Reichelt,J., Lunny,D.P., Magin,T.M. and Lane,E.B. (1998) The relationship between hyperproliferation and epidermal thickening in a mouse model for BCIE. J. Invest. Dermatol., 110, 951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punnonen K., Denning,M., Lee,E., Li,L., Rhee,S.G. and Yuspa,S.H. (1993) Keratinocyte differentiation is associated with changes in the expression and regulation of phospholipase C isoenzymes. J. Invest. Dermatol., 101, 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S.G. and Bae,Y.S. (1997) Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 15045–15048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini M.P., Talora,C., Seki,T., Bolgan,L. and Dotto,G.P. (2001) Cross talk among calcineurin, Sp1/Sp3 and NFAT in control of p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression in keratinocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 9575–9580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarlata S., Gupta,R., Garcia,P., Keach,H., Shah,S., Kasireddy,C.R., Bittman,R. and Rebecchi,M.J. (1996) Inhibition of phospholipase C-δ1 catalytic activity by sphingomyelin. Biochemistry, 35, 14882–14888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Ullrich R., Aebischer,T., Hulsken,J., Birchmeier,W., Klemm,U. and Scheidereit,C. (2001) Requirement of NF-κB/Rel for the development of hair follicles and other epidermal appendices. Development, 128, 3843–3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz C.S., Lin,Q., Deng,H. and Khavari,P.A. (1998) Alterations in NF-κB function in transgenic epithelial tissue demonstrate a growth inhibitory role for NF-κB. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 2307–2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimohama S., Homma,Y., Suenaga,T., Fujimoto,S., Taniguchi,T., Araki,W., Yamaoka,Y., Takenawa,T. and Kimura,J. (1991) Aberrant accumulation of phospholipase C-δ in Alzheimer brains. Am. J. Pathol., 139, 737–742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh P.G., Ryu,S.H., Choi,W.C., Lee,K.Y. and Rhee,S.G. (1988) Monoclonal antibodies to three phospholipase C isozymes from bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem., 263, 14497–14504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale J. and Beachy,P.A. (2001) The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature, 411, 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Ziboh,V.A., Isseroff,R. and Martinez,D. (1988) Turnover of inositol phospholipids in cultured murine keratinocytes: possible involvement of inositol triphosphate in cellular differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol., 90, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G., Lehrer,M.S., Jensen,P.J., Sun,T.T. and Lavker,R.M. (2000) Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell, 102, 451–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hogerlinden M., Rozell,B.L., Ahrlund-Richter,L. and Toftgard,R. (1999) Squamous cell carcinomas and increased apoptosis in skin with inhibited Rel/nuclear factor-κB signaling. Cancer Res., 59, 3299–3303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancurova I., Miskolci,V. and Davidson,D. (2001) NF-κB activation in tumor necrosis factor α-stimulated neutrophils is mediated by protein kinase Cδ. Correlation to nuclear IκBα. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 19746–19752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma I.M., Stevenson,J.K., Schwarz,E.M., Van Antwerp,D. and Miyamoto,S. (1995) Rel/NF-κB/IκB family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev., 9, 2723–2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt F.M. and Hogan,B.L. (2000) Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science, 287, 1427–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z. and Bikle,D.D. (1999) Phospholipase C-γ1 is required for calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 20421–20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagisawa H., Emori,Y. and Nojima,H. (1991) Phospholipase C genes display restriction fragment length polymorphisms between the genomes of normotensive and hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens., 9, 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.W., Wynder,C., Doughty,M.L. and Heintz,N. (1999) BAC-mediated gene-dosage analysis reveals a role for Zipro1 (Ru49/Zfp38) in progenitor cell proliferation in cerebellum and skin. Nat. Genet., 22, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]