Abstract

The timing of the transition to flowering is critical for reproductive success in plants. Arabidopsis FCA encodes an RNA-binding protein that promotes flowering. FCA expression is regulated through alternative processing of its pre-mRNA. We demonstrate here that FCA negatively regulates its own expression by ultimately promoting cleavage and polyadenylation within intron 3. This causes the production of a truncated, inactive transcript at the expense of the full-length FCA mRNA, thus limiting the expression of active FCA protein. We show that this negative autoregulation is under developmental control and requires the FCA WW protein interaction domain. Removal of introns from FCA bypasses the autoregulation, and the resulting increased levels of FCA protein overcomes the repression of flowering normally conferred through the up-regulation of FLC by active FRI alleles. The negative autoregulation of FCA may therefore have evolved to limit FCA activity and hence control flowering time.

Keywords: Arabidopsis/autoregulation/FCA/flowering/polyadenylation

Introduction

The switch from vegetative to reproductive development is the major developmental transition in flowering plants (Mouradov et al., 2002; Simpson and Dean, 2002). The integration of environmental signals and the endogenous developmental competence of the plant determine the timing of this transition. Flowering time is closely allied to seasonal progression and is an important trait govern ing adaptation to environment. Naturally occurring Arabidopsis ecotypes have evolved two broadly different flowering strategies: rapid cycling and a winter annual habit (Simpson and Dean, 2002). Rapid cycling accessions complete their life-cycle in as little as 6 weeks and may complete more than one life cycle in a growing season. This is one property that has led to the widespread use of Arabidopsis as a model for plant biology, and the most commonly studied laboratory accessions, Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Columbia (Col), are in this class. However, most naturally occurring Arabidopsis ecotypes are winter annuals. That is, they germinate before winter and flower in the favourable conditions of the following spring. Winter annuals therefore complete only one life-cycle in a growing season. Unlike rapid cycling accessions, winter annuals require the long cold treatment of winter to accelerate flowering, in a process known as vernalization.

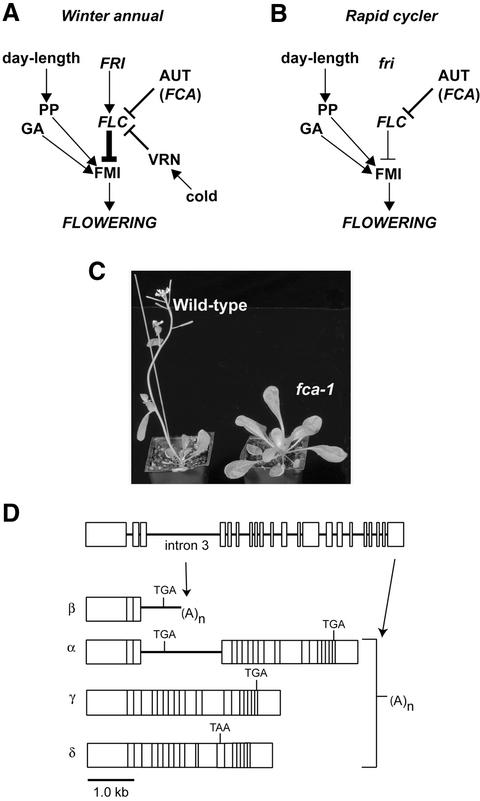

In Arabidopsis, genes that promote flowering have been identified through the characterization of late flowering mutants (Koornneef et al., 1991). These genes have been placed into genetically separable pathways on account of the shared phenotypic and epistatic interactions of the corresponding mutants (Mouradov et al., 2002; Simpson and Dean, 2002). A simplified representation of these pathways is shown in Figure 1A and B. Flowering in Arabidopsis is promoted by long days and the photoperiod pathway mediates this response. In addition, a genetically separable gibberellin signal transduction pathway promotes flowering in both long and short day conditions (Mouradov et al., 2002; Simpson and Dean, 2002). These pathways ultimately activate genes that switch meristem identity from vegetative to floral and thus execute the floral transition. The capacity of these pathways to promote flowering is antagonized by a key repressor of the Arabidopsis floral transition, the MADS-domain transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) (see Hepworth et al., 2002; Simpson and Dean, 2002). The expression of FLC correlates with flowering time, with high levels of FLC mRNA being associated with late flowering (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). FLC expression is regulated by pathways that act antagonistically to either promote or down-regulate its expression (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). FLC expression is down-regulated by the autonomous pathway (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). However, in winter annual accessions like San Feliu-2 (SF-2), active FRIGIDA (FRI) alleles override the activity of the autonomous pathway and promote elevated levels of FLC mRNA expression (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999) (Figure 1A). This function of FRI is antagonized by the vernalization pathway, which acts to down-regulate FLC in response to the long cold temperature treatment of winter (Sheldon et al., 1999, 2000; Gendall et al., 2001) (Figure 1A). In rapid cycling accessions, like Ler, that carry loss-of-function fri alleles (Johanson et al., 2000), the autonomous pathway is the major pathway controlling the expression of FLC (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1. FCA and the control of Arabidopsis flowering time. (A and B) Schematic representation of the principal genetic pathways controlling flowering time in winter annual and rapid cycling accessions of Arabidopsis. Promotive activities are denoted by arrowheads, repressive activities are denoted by T-bars. The photoperiod (PP) and gibberellin signal transduction (GA) pathways are shown activating genes with a floral meristem identity function (FMI), while FLC is shown to repress this. FRI, the FCA-containing autonomous pathway (AUT) and vernalization pathway (VRN) regulate FLC in an antagonistic manner. The most frequently found difference between winter annual (A) and rapid cycling (B) Arabidopsis accessions is allelic variation at FRI, with most rapid cycling accessions carrying inactive, loss-of-function fri alleles. (C) A comparison of the phenotype of wild-type Ler plants and late flowering fca-1 mutant plants. Although grown for the same time and under identical conditions, wild-type plants have already flowered while the fca-1 plants have remained in the vegetative state and continued to produce more leaves as opposed to floral organs. (D) Schematic representation of the alternative processing of Arabidopsis FCA pre-mRNA. Exons are represented as filled boxes and intron by lines.

The autonomous pathway is currently defined by six recessive late-flowering mutants, fca, fy, fve, fld, ld and fpa, all of which flower later than wild type in both long and short day conditions (Koornneef et al., 1998). Each appears to negatively regulate FLC, since autonomous pathway mutant backgrounds show elevated levels of FLC mRNA (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). In addition, the early flowering flc-3 null mutation is epistatic to autonomous pathway mutations, indicating that the regulation of FLC expression can account for their late flowering phenotype (Michaels and Amasino, 2001). In contrast to the environmental inputs that control the photoperiod and vernalization pathways, it is not known how the activity of the autonomous pathway is regulated.

In order to understand how the autonomous pathway is controlled, we are analysing the pathway component, FCA, which encodes a protein with two RRM-type RNA binding domains and a WW protein interaction domain (Macknight et al., 1997). The late flowering allele, fca-1 (Figure 1C), results from a point mutation in exon 13 that introduces a premature stop codon. A truncated FCA protein expressed from this mutated gene lacks the WW domain (Macknight et al., 1997). FCA expression is regulated post-transcriptionally by alternative processing of the pre-mRNA. Four different transcripts are processed from FCA pre-mRNA: α, β, δ and γ (Figure 1D). FCA-γ and -δ transcripts result from excision of all introns, but they are distinguished by an alternative splicing event around intron 13 that produces transcript δ. While γ encodes the full-length active FCA protein, the alternative splicing that produces transcript δ results in a shift in reading frame that leads to the introduction of a premature termination codon (PTC). As a result, δ mRNA encodes a truncated isoform of FCA that lacks the WW domain. Transcript α retains intron 3, but all other introns are excised. The fourth transcript, β, arises from cleavage and polyadenylation within intron 3. Because of the presence of in-frame stop codons within intron 3 (Figure 1D), both α and β encode truncated isoforms of FCA that lack intact RNA binding domains. While FCA-β is cleaved and polyadenylated at a promoter-proximal site within intron 3, the other transcripts are cleaved and polyadenylated at a distal site in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) (Figure 1D). Therefore, the processing of FCA pre-mRNA involves alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation, with three different transcripts resulting from the alternative processing of intron 3. Only the fully spliced FCA-γ transcript appears to be functional in flowering time control, since the overexpression of the other transcripts neither promotes flowering in an fca-1 background nor delays it in wild type (Macknight et al., 1997, 2002). The conservation of the alternative processing of FCA pre-mRNA in other plants and its temporal and spatial regulation (Macknight et al., 2002) suggests that it plays a key role in regulating FCA expression levels.

In this report we show that FCA negatively regulates its expression by ultimately promoting proximal poly(A) site usage within intron 3 of its own pre-mRNA. We show that FCA is a nuclear RNA-binding protein and that its WW domain is required for this autoregulation. This post-transcriptional regulation has a functional consequence for growth, development and flowering time. The removal of this control through the use of intronless transgenes changed the balance of the activities of pathways regulating FLC mRNA levels, resulting in precocious flowering.

Results

Endogenous FCA protein expression is undetectable in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing FCA from a transgene

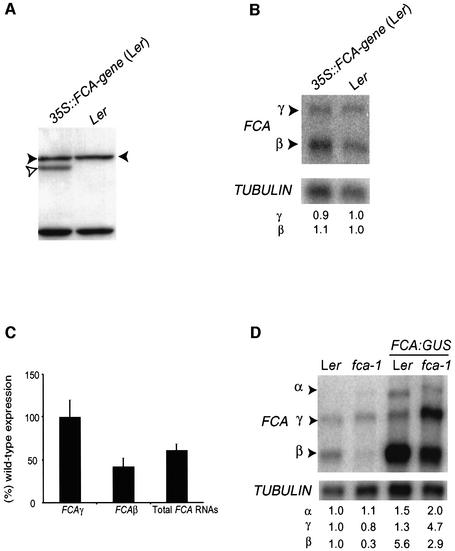

FCA can be overexpressed in stable transgenic lines from a transgene consisting of a cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter driving the expression of an intronless FCA gene (Macknight et al., 2002). In constructing this transgene, the CaMV 35S promoter was inserted at position +349 (relative to the FCA transcription initiation site) and upstream of the first in-frame AUG codon (Macknight et al., 2002; see Figure 2A). As a result, sequences encoding the first 349 nucleotides of the 5′ end of the FCA transcript are deleted from this construct. We have subsequently discovered that translation of endogenous FCA actually initiates at a non-AUG codon upstream of the first in-frame AUG (Figure 2A; unpublished data) and as a result, the protein expressed from this transgene is 10 kDa shorter than the native or endogenous FCA protein (Macknight et al., 2002). However, the truncated transgene-derived protein is functional, since it complements the late-flowering phenotype of fca-1 by reducing the levels of FLC mRNA (Macknight et al., 2002). The difference in size between the endogenous and transgene-derived proteins should have enabled their simultaneous detection in Western analysis with anti-FCA antibodies. When 35S::FCA-γ was introduced into a wild-type Ler background from an fca-1 mutant background by crossing (hereafter referred to as introgression), we were able to confirm that the truncated FCA protein derived from the transgene was overexpressed in both backgrounds. However, we were unable to detect the simultaneous expression of the transgene-derived protein with either full-length endogenous FCA protein or the truncated mutant protein derived from fca-1 (Figure 2B). This suggested that the overexpression of FCA from a transgene was associated with reduced expression of FCA protein from the endogenous gene.

Fig. 2. FCA negatively autoregulates its expression at the level of poly(A) site choice. (A) Schematic representation illustrating the differences between the endogenous FCA gene and 35S::FCA-γ transgene. The CaMV 35S promoter is inserted at a site upstream of the first in-frame AUG codon, resulting in the deletion of 349 bp of FCA exon 1 from 35S::FCA transgenes. The position of the non-canonical initiation codon from which FCA is translated is denoted with an asterisk. The region used as a probe in northern analysis is denoted by a hatched bar. (B) Immunodetection of FCA protein. Western blot analysis of total soluble protein extracts from seedlings of Ler, fca-1, and the transgenic lines 35S::FCA-γ in Ler and 35S::FCAγ in fca-1 (a 35S fusion to an intronless FCA transgene). Filled and unfilled arrowheads denote endogenous and transgenic FCA proteins respectively. Lower bands are unspecific binding products used as loading controls. (C) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler, fca-1, fca-4, and the transgenic lines 35S::FCA-γ in Ler and 35S::FCA-γ in fca-1 [the transgene described in (A)]. The blot was probed first with an FCA 5′ leader probe and later stripped and re-probed with a β-TUBULIN probe as a loading control. Numbers below compare the expression level of each FCA transcript between the different samples analysed. They were calculated as a ratio between a normalized FCA transcript signal (against that for β-TUBULIN) of a given sample and the same FCA transcript signal normalized in the wild type (Ler).

Negative regulation of FCA expression occurs at the level of intron 3 processing

In order to determine the molecular basis for reduced expression of endogenous FCA protein in plants overexpressing transgenic FCA, we analysed endogenous FCA gene expression at the RNA level. Northern analysis was performed using poly(A)+ RNA purified from wild-type (Ler), loss-of-function fca-1 and fca-4 alleles, and from transgenic plants overexpressing FCA in either a Ler or a fca-1 mutant background (Figure 2C). To detect only the expression of the endogenous FCA gene, a probe to the 5′ end of FCA was used (Figure 2A). This region is present in all the isoforms generated by alternative processing of endogenous FCA pre-mRNA, but is absent from the FCA transgene (Macknight et al., 2002). To confirm the identity of the different FCA transcripts we included fca-4 as a positive control. fca-4 is a γ-ray-induced allele containing a breakpoint and chromosomal rearrangement within intron 4 of FCA (Page et al., 1999). This results in FCA intron 4 being fused to the predicted gene, At4g1550 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. Z97335). Since FCA-β results from cleavage and polyadenylation within intron 3, it should be the same size in fca-4 as in wild-type plants. However, since transcripts α, δ and γ are processed to include both the 5′ part of FCA and the fusion to the rearranged gene downstream, they should differ in size between fca-4 and wild-type.

Transcripts corresponding to FCA-β, -α and -γ were detected by northern analysis in wild-type plants (Figure 2C). FCA-β was the same size in fca-4 as in wild type, whereas transcripts α and γ were smaller in fca-4 compared with wild type (Figure 2C), confirming identification of the correct transcripts (FCA-δ was not detected using this approach because of its low abundance and similarity in size to γ; Macknight et al., 1997). FCA-β was detected in both 35S::FCA-γ lines overexpressing FCA; however, transcripts α and γ were not (Figure 2C). The presence of increased levels of transcript β (which arises from cleavage and polyadenylation at the proximal site within intron 3) and the corresponding absence of transcripts cleaved and polyadenylated at the distal site (α and γ) indicates that the negative regulation of endogenous FCA expression occurs at the post-transcriptional level, ultimately through a shift in poly(A) site choice. The absence of transcript γ explains our inability to detect full-length FCA protein in these lines. The comparison of the ratio of the FCA transcripts in wild-type and the loss-of-function fca-1 and fca-4 mutants showed that less β and more α transcript accumulates in fca mutants (Figure 2C). This indicates that regulation of intron 3 processing may be a normal feature of FCA function and regulation, and not simply a gain-of-function phenotype from the ectopic overexpression of an FCA transgene.

We conclude that the negative regulation of FCA expression occurs post-transcriptionally, at the level of splicing versus poly(A) site selection at intron 3, and that this is a normal feature of the regulation and activity of FCA.

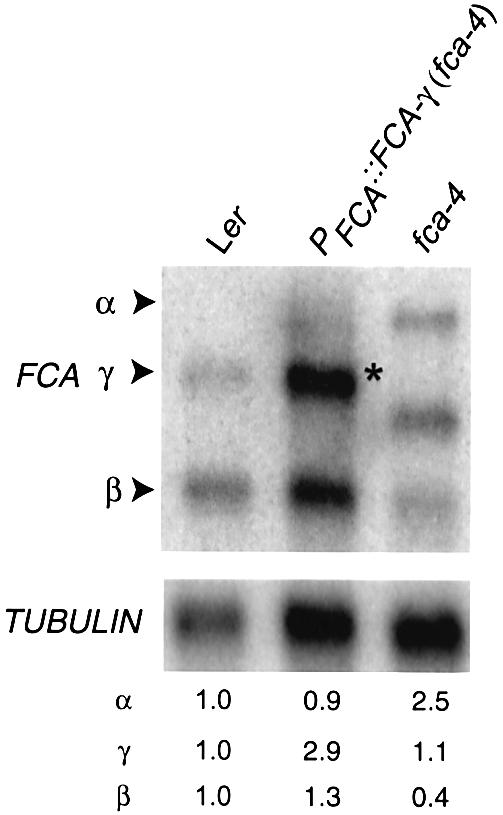

FCA negatively regulates its expression ultimately by promoting proximal poly(A) site usage of its own pre-mRNA

The regulation of FCA mRNA 3′ end formation could result from two alternative mechanisms. The overexpression of FCA may result in the inhibition of cleavage and polyadenylation at the distal site in the conventional 3′UTR, with the proximal site within intron 3 then being used by default. Alternatively, the overexpression of FCA may actively promote proximal poly(A) site selection (either directly, or as a consequence of affecting splicing of intron 3), so that all transcripts are cleaved and polyadenylated within intron 3. To distinguish between these possibilities, we made use of the fca-4 allele. In this background, the proximal and distal poly(A) sites are physically separated by the chromosomal breakpoint and rearrangement and are therefore expressed on separate transcripts. We reasoned that if the responsive cis-elements to this control lay at the proximal site, then overexpression of FCA in an fca-4 background should result in increased accumulation of the β transcript. However, if the responsive cis-elements lay at the FCA distal site, then the accumulation of FCA-β should be unaffected by FCA overexpression in fca-4. To test this, we introduced a transgene (PFCA::FCA-γ) expressing a full-length, intronless FCA gene driven by the endogenous promoter into fca-4. Significantly, we detected increased accumulation of endogenous FCA-β transcripts and a corresponding disappearance of the size-shifted fca-4 α and γ transcripts (Figure 3). These data are all consistent with FCA ultimately promoting selection of the proximal poly(A) site.

Fig. 3. FCA actively promotes the use of the proximal poly(A) site in its pre-mRNA. Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler, fca-4 and the transgenic line PFCA::FCA-γ in fca-4 (an intronless FCA transgene fused to the native FCA promoter). Blot was probed as indicated in Figure 2C. Numbers denote relative expression and were calculated as in Figure 2C. Asterisk denotes the FCA-γ transcript belonging to the PFCA::FCA-γ transgene.

Autoregulation of FCA expression requires an intact FCA WW domain

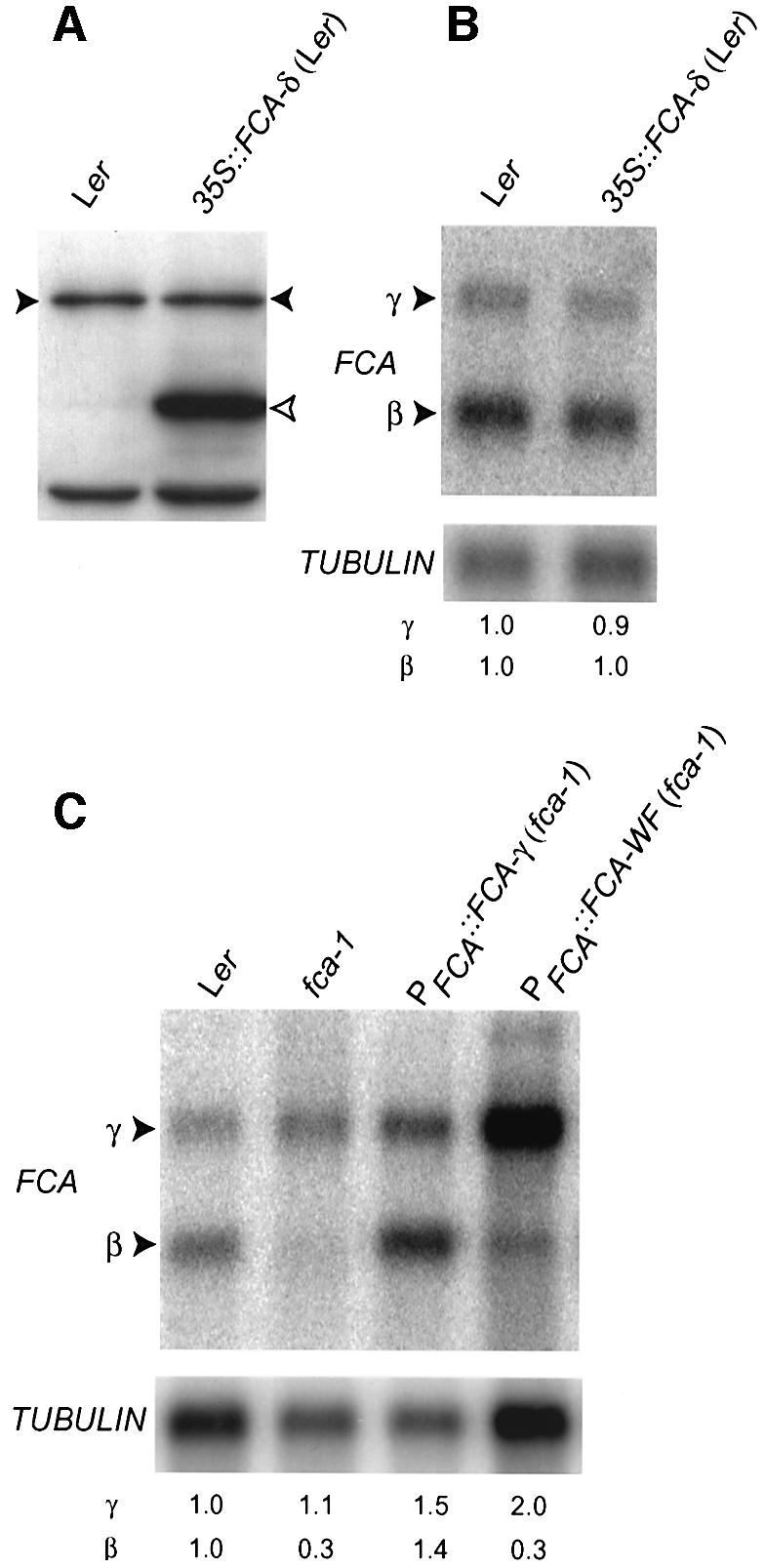

To determine whether the RNA-binding domains of FCA were sufficient for the negative feedback control, we examined the effects of overexpressing FCA-δ from an intronless transgene driven by the CaMV 35S promoter (35S::FCA-δ) in a Ler background. This isoform encodes the RNA binding domains of FCA but lacks an intact WW protein interaction domain. Overexpression of FCA-δ protein had no effect on either the expression of endogenous FCA protein (Figure 4A) or the pattern of endogenous FCA mRNA expression (Figure 4B). This is consistent with the observed negative regulation not simply being the result of ectopically overexpressing an RNA binding protein in these plants. Since FCA-δ lacks the WW protein interaction domain as well as other C-terminal sequences of FCA, we tested whether the WW domain was necessary for the negative regulation of FCA expression. The second signature tryptophan of the WW domain was mutated to phenylalanine, and plants expressing this WF mutant protein in an fca-1 mutant background accumulated wild-type levels of this protein (Simpson et al., 2003). While the increased accumulation of β transcript could be detected in fca-1 plants expressing intact FCA from an intronless transgene, no increase in the accumulation of β could be detected in fca-1 plants expressing the WF mutation (Figure 4C). We therefore conclude that the autoregulation of FCA expression requires an intact WW domain.

Fig. 4. FCA autoregulation requires an intact WW domain. (A) Immunodetection of FCA protein. Western blot analysis of total soluble protein extracts from seedlings of Ler and the transgenic line 35S::FCA-δ in Ler (a 35S fusion to an intronless FCA-δ transgene). Lower bands are unspecific binding products used as loading controls. Filled and unfilled arrowheads denote endogenous and transgenic FCA proteins, respectively. (B) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler and the transgenic line 35S::FCA-δ in Ler [the same transgenic line as reported in (A)]. The blot was probed as indicated in Figure 2C. Numbers denote relative expression and were calculated as in Figure 2C. (C) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler, fca-1, and the transgenic lines PFCA::FCA-γ in fca-1 (the same transgene reported in Figure 3) and PFCA::FCA-WF in fca-1 (an intronless FCA transgene fused to the endogenous promoter carrying a mutation resulting in a tryptophan to phenylalanine substitution in the WW domain). The blot was probed as indicated in Figure 2C. Numbers denote relative expression and were calculated as in Figure 2C.

FCA is a nuclear protein

As FCA is an RNA-binding protein (Macknight et al., 1997) it is possible that it carries out the negative regulation of its expression directly. In order to establish whether this was a possibility, we determined whether FCA was nuclear localized. A chimeric FCA:GUS fusion protein was transiently expressed in onion epidermal cells (Varagona et al., 1992). When transfected with a plasmid expressing only the GUS protein, cells showed a uniform distribution of GUS activity (not shown). In contrast, cells transfected with FCA:GUS showed GUS activity predominantly in the nucleus indicating that FCA is a nuclear-localized protein (Figure 5A and B).

Fig. 5. Nuclear localization of FCA protein. (A) Histochemical staining for GUS activity (dark staining) of transiently transfected onion epidermal cells. (B) DAPI counter staining of same cells as in (A), revealing location of nuclei.

Autoregulation of FCA expression normally controls the levels of active FCA transcript γ

The presence of introns in the 35S::FCA-gene limited the capacity of FCA-γ RNA to be overexpressed (Macknight et al., 1997, 2002). As shown in Figure 2B, when the truncated transgenic FCA protein was expressed from an intronless construct with the 35S promoter (35S::FCA-γ), full-length endogenous FCA protein could not be detected. However, when this same truncated FCA protein was expressed from a transgene that contained all the endogenous FCA introns (35S::FCA-gene), we detected low levels of the transgenic protein and were still able to detect the endogenous wild-type protein (Figure 6A). In addition, RNA expression from the endogenous FCA gene was unaffected (Figure 6B). These findings support the idea that autoregulation of FCA expression prevents overexpression of the active FCA-γ isoform.

Fig. 6. FCA autoregulation controls the level of functional transcript γ. (A) Immunodetection of FCA protein. Western blot analysis of total soluble protein extracts from seedlings of Ler and the transgenic line 35S::FCA-gene (a 35S fusion to the FCA gene) in Ler. Filled and unfilled arrowheads denote endogenous and transgenic FCA proteins, respectively. Lower bands are unspecific binding products used as loading controls. (B) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler and the transgenic line 35S::FCA-gene in Ler [the same transgene as in (A)]. The blot was probed as indicated in Figure 2C. Numbers denote relative expression and were calculated as in Figure 2C. (C) Quantification of the FCA transcripts levels in the fca-1 mutant. Data are the average of six different experiments and the FCA transcript signals obtained by northern analysis were normalized against that for β-TUBULIN. (D) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from Ler, fca-1, and the transgenic lines PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS in Ler and PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS in fca-1. The blot was probed as indicated in Figure 2C. Numbers denote relative expression and were calculated as in Figure 2C.

Quantitation of transcript levels in fca-1 revealed that while the level of FCA-β was reduced compared with wild type, there was no corresponding difference in the steady state level of FCA-γ between these plants (Figure 6C). If the negative feedback regulation had a functional consequence for the level of active FCA expression, one would have expected the levels of transcripts β and γ to change reciprocally, i.e. if less pre-mRNA was cleaved and polyadenylated at the promoter proximal site, more pre-mRNA should be available for processing at the distal site. One explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that FCA transcripts in fca-1 mutant plants might be subject to nonsense-mediated decay (Hentze and Kulozik, 1999) due to the introduction of a PTC within exon 13 in fca-1 (Macknight et al., 1997). The transcripts α, γ and δ would all carry this PTC, but FCA-β would not. Equal amounts of β can be detected in fca-1 mutant and wild-type plants overexpressing FCA from the 35S::FCA-γ transgene (see Figure 2C). However, when all the FCA transcripts are quantified, ∼35% less FCA RNA can be detected in fca-1 compared with wild type (Figure 6C). This supports the idea that the steady-state levels of the γ transcript in fca-1 mutant plants are lower than might be expected because of the susceptibility of this transcript to nonsense-mediated decay. Therefore, in fca-1 the expected reciprocal increase in γ levels may be effectively masked by the effect that the PTC has on RNA accumulation.

To test whether the removal of FCA autoregulation would result in elevated levels of the γ transcript in another way, we examined the processing of FCA intron 3 in transgenic plants stably expressing an FCA:GUS reporter gene fusion (PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS) (Macknight et al., 2002). We monitored the effects of loss of FCA function on the processing of FCA intron 3 in vivo by comparing the profile of transcripts expressed from this transgene in wild-type and fca-1 backgrounds. As shown in Figure 6D, there is indeed a corresponding shift in the accumulation of β and γ transcripts between wild type and fca-1: less FCA-β, but more FCA:GUS-γ accumulates in fca-1 compared with wild type.

We conclude that the negative regulation in wild-type plants will cause changes in abundance of the active FCA-γ transcript, and therefore is likely to have a functional consequence for the control of flowering time.

Autoregulation of FCA expression controls the temporal and spatial distribution of active FCA

The processing of FCA intron 3 limits FCA expression in a temporal and spatial dependent manner, restricting elevated levels of γ expression to proliferating cells and to a level that was undetectable (by histochemistry) until 4–6 days after germination (Macknight et al., 2002). To assess the in vivo relevance of negative feedback regulation on this pattern, the expression of the PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS transgene was compared histochemically in fca-1 and wild-type backgrounds. As we had reported previously (Figure 7A–D; Macknight et al., 2002), GUS activity (and by extension, intron 3 excision) cannot be detected until 4–6 days after germination in a wild-type background. When GUS activity is detected, it is limited to regions of active cell proliferation in the shoot and root apices (Figure 7B–D). However, in fca-1, GUS activity is detected earlier (2 days after germination) and in a much broader distribution (Figure 7E–H); i.e. vasculature of cotyledons, shoot apex, emerging leaf primordia, main and lateral roots and in developed leaves. This pattern more closely resembles the expression of FCA promoter:GUS fusions (Macknight et al., 2002). We interpret these data to show that FCA is normally constitutively transcribed, but the negative feedback maintains γ at a low level throughout much of the plant. This autoregulation, however, is either less efficient or does not function in meristematic cells at a specific time in development.

Fig. 7. Histochemical assay for GUS activity in seedlings expressing PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS in a Ler or fca-1 background. (A–D) PFCA:: FCAto exon 5:GUS (Ler) at 2 (A), 4 (B), 6 (C) and 10 (D) days after germination. (E–H) PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS (fca-1) at 2 (E), 4 (F), 6 (G) and 10 (H) days after germination. All panels show seedlings incubated with X-Gluc for 16 h.

We therefore conclude that the autoregulation of FCA expression at the level of intron 3 processing governs the level of active FCA expression in a temporally and spatially dependent manner.

High overexpression of FCA perturbs Arabidopsis development

The 35S::FCA-γ transgenic line described above carried a fusion between the CaMV 35S promoter and the FCA cDNA (Macknight et al., 2002). Except for flowering earlier, these plants had a similar phenotype to the wild-type Ler. We had previously also generated lines carrying a fusion of the CaMV 35S promoter, chlorophyll a/b binding gene 22L 5′ untranslated leader and the FCA cDNA (35S::cab-FCA-γ), and these lines showed much higher levels of FCA protein than 35S::FCA-γ (Macknight et al., 2002). The highest expressing 35S::cab-FCA-γ lines showed additional phenotypes apart from early flowering (Figure 8) that ranged from small stature (Figure 8C) and premature senescence of rosette leaves (Figure 8D) to arrested development, epinasty and yellowing of the leaves, premature senescence and death (Figure 8F and G). The occurrence of these phenotypes correlated with the level of FCA protein (data not shown). These deleterious effects of FCA overexpression might therefore account for the fine control of FCA expression levels and the evolution of an autoregulatory mechanism.

Fig. 8. High overexpression of FCA is detrimental for Arabidopsis development. (A) Wild-type Ler plants grown in long day photoperiod (16 h light) and (B) close-up of rosette leaves. (C) A transgenic plant expressing the 35S::cab-FCA-γ transgene, grown under the same conditions as the wild-type plant shown in (A). (D) A close-up of the rosette leaves of the plants shown in (C). (E) Wild-type Ler seedlings. (F) 35S::cab-FCA-γ plants that gave a more severe phenotype, shown at the same magnification as (E). (G) The 35S::cab-FCA-γ plants that gave a more severe phenotype, shown at a higher magnification.

FCA autoregulation prevents precocious flowering

A second rationale for establishment and maintenance of FCA negative autoregulation might be to avoid precocious flowering by controlling FLC expression. FCA functions in parallel to the vernalization pathway to down-regulate RNA levels of the floral repressor FLC. FRI acts antagonistically to these pathways to up-regulate FLC expression levels (Simpson and Dean, 2002). To investigate the relevance of the FCA negative feedback control on flowering time, we introgressed the intronless PFCA::FCA-γ transgene with expression driven by the native FCA promoter, as described above, into Ler plants carrying an active FRI allele (introgressed from the SF-2 accession). Ler plants with a functional FRI allele flower later than Ler plants without active FRI (Table I). However, the presence of the FCA-γ transgene overcomes FRI epistasis and plants flower earlier (Table I). The expression of FCA is unaffected in an active FRI background (G.G.Simpson, R.Macknight and C.Dean, in preparation) and thus this distinction is not related to FRI controlling the processing of FCA pre-mRNA. The acceleration of flowering by the PFCA::FCA-γ transgene in a Ler background is relatively modest, since FLC mRNA levels are already low and its role in repressing flowering is minor. However, in winter annuals with active FRI alleles, the dramatic up-regulation of FLC mRNA constitutes the major activity repressing flowering. Therefore, we conclude that removal of the capacity for FCA autoregulation results in an increase in FCA activity that can perturb the balance of the pathways controlling FLC expression, and hence flowering time.

Table I. Flowering time, measured as leaf number, of lines carrying a FCA-γ transgene.

| Construct | Background | Line | Leaf no. in long daysa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ler | 8.6 ± 0.1 | ||

| FCA-γ | Ler | FCA-γ-20-2 | 8.1 ± 0.2 |

| FRI (SF-2) | 21.8 ± 0.3 | ||

| FCA-γ | FRI (SF-2) | FCA-γ-20-2 | 13.5 ± 0.3 |

aErrors indicate ±SE.

Discussion

In this report we show that FCA negative autoregulation results from FCA ultimately promoting premature cleavage and polyadenylation of its own pre-mRNA. This negative feedback functions to limit the level of active FCA-γ expression in a temporally and spatially dependent manner. We demonstrate that FCA autoregulation has functional consequences for Arabidopsis development, since it limits active FCA-γ expression, which is limiting for the floral transition, and it prevents increased expression of FCA-γ, which can be deleterious to Arabidopsis viability. Increased levels of FCA-γ alters the balance of pathways controlling flowering time leading to precocious flowering. Our analysis provides insight into a novel example of post-transcriptional autoregulation, which has important consequences for the life-cycle of Arabidopsis.

This negative regulation provides an explanation for our previous failure to overexpress FCA-γ protein from intron-containing transgenes (Macknight et al., 1997, 2002): When FCA-γ protein reaches a threshold level it will ultimately promote proximal poly(A) site selection within intron 3 of its own pre-mRNA, and therefore prevent the further accumulation of γ transcript. Consistent with this, we had previously found a dramatic increase in the accumulation of FCA-β, but only a modest increase in γ levels, when the FCA gene was overexpressed with the CaMV 35S promoter (Macknight et al., 1997). Consequently, it is only when the cis element within intron 3 required for this negative feedback is removed that active FCA-γ transcript can be overexpressed. FCA is a highly conserved plant protein and the alternative processing of its pre-mRNA is also conserved (Macknight et al., 2002). The relatively large size of intron 3 is conserved in FCA from other plants and transcripts equivalent to FCA-β and -γ can be detected in all plant species that we have examined (Macknight et al., 2002; unpublished data). This suggests that attempts to manipulate flowering time in other plants by the overexpression of FCA may also require the removal of intron 3 from expression constructs.

The processing of FCA intron 3 limits FCA-γ expression in a temporal and spatial dependent manner (Macknight et al., 2002). The production of elevated levels of transcript γ is restricted to regions of active cell proliferation such as the shoot and root apices, and this up-regulation cannot be detected until 4–6 days after germination. Our analysis here indicates that FCA is present and functional in regulating its own expression before then. This has implications for understanding how FCA regulates FLC levels, as it suggests that FCA might also regulate FLC expression throughout the plant and not just within the meristematic regions. Alternatively, the localized elevated level of FCA expression seen in proliferating apical cells at 4–6 days after germination may be associated with the timed down-regulation of FLC expression. Since elevated levels of FLC expression can be detected by northern analysis of fca-1 seedlings at 3 days after germination (Gendall et al., 2001), the localized up-regulation of FCA expression does not seem to be a prerequisite for its ability to regulate FLC. In order to distinguish between these possibilities we are now examining the expression of FLC:GUS reporters in these backgrounds in detail.

That transcript γ accumulates in regions of active cell proliferation at a specific time in development indicates that FCA negative feedback is less effective in these cells at this time. Since these regions are actively dividing prior to this localized upregulation of FCA expression, this distinction cannot be correlated with cell proliferation alone. Notably, we have found that the expression pattern of the PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS transgene is unaffected when combined with 35S::FCA-γ (data not shown). This indicates that these regions are resistant to negative feedback of FCA expression. This may be due to an increased activity of splicing factor(s) in these cells promoting intron 3 excision or a reduction in polyadenylation factor(s) required to carry out negative feedback. It has previously been shown that cell-specific changes in the expression level of constitutive RNA processing factors such as the essential polyadenylation factor, CstF64, can affect poly(A) site selection and alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs (Takagaki et al., 1996). FCA-β and -α appear to be non-functional by-products of the negative regulation of FCA expression by proximal poly(A) site selection. Since negative regulation by proximal poly(A) site usage is not effective in apical meristems, then the alternative splicing that produces FCA-δ (which is also non-functional in flowering time control; Macknight et al., 2002) may have evolved as another means to negatively regulate FCA expression in these cells.

To begin to address the molecular basis of FCA mediated negative feedback we showed that cleavage and polyadenylation of intron 3 is ultimately promoted by FCA and is not an indirect effect resulting from FCA blocking the use of the distal poly(A) site. Given that FCA can bind RNA in vitro (Macknight et al., 1997), it is possible that FCA protein binds to its own pre-mRNA to control this processing directly. Consistent with this possibility and the fact that pre-mRNA processing is a nuclear event, we found that FCA is localized to the nucleus. Since an intact FCA WW protein interaction domain is required for this regulation, it is possible that FCA interacts with factors that either inhibit splicing of intron 3 or promote proximal poly(A) site usage more directly. Alternative polyadenylation can be intimately connected to alternative splicing as the analysis of mammalian calcitonin/CGRP and immunoglobulin transcripts has revealed (for a review, see Zhao et al., 1999). The processing choice in FCA most closely resembles that found in IgM heavy chain transcripts, where two poly(A) sites, each forming part of a different 3′ terminal exon, are present on the primary transcript. The competing processing sites that define the splicing and polyadenylation signals are suboptimal, and it has been proposed that small changes in the efficiency of either the splicing or polyadenylation reactions could tip the balance in favour of one of the processing reactions. Consistent with this, changes in the abundance of either splicing or polyadenylation factors can alter the efficiency of these respective processing events (Zhao et al., 1999). It is possible that a different mechanism is involved in the regulation of FCA. Since we found no increase in the transcript α (from which intron 3 is not processed) when FCA was overexpressed, and indeed found elevated levels of unspliced intron 3 in loss-of-function fca backgrounds, it seems more likely that FCA promotes poly(A) site selection rather than inhibits splicing. Consistent with this, we have recently found that FCA interacts with a conserved 3′ end processing factor, Pfs2p/FY, through its WW domain and that this interaction is genetically required for FCA autoregulation (Simpson et al., 2003). Clearly, it will be interesting to dissect this process further at the molecular level.

In other cases of post-transcriptional autoregulation of gene expression by RNA binding proteins the mechanism involved is closely related to the normal function these proteins perform. For example the splicing factors Drosophila tra-2 (McGuffin et al., 1998) and Arabidopsis atSRp30 (Lopato et al., 1999) autoregulate their expression by controlling splice-site selection of their own pre-mRNAs. However, not all autoregulation of RNA-binding protein expression occurs by a mechanism related to their normal function. For example, the mammalian splicing factor, U1A, autoregulates its expression by inhibiting polyadenylation of its own pre-mRNA (Boelens et al., 1993; Gunderson et al., 1994). Nevertheless, these findings at least raise the possibility that FCA functions in the control of flowering time through the control of 3′ end formation. Northern analysis has not yet revealed a significant reciprocal accumulation of full-length FLC and truncated FLC transcripts in wild-type and mutant fca plants, but we do not yet know whether the regulation of FLC by FCA is direct. In addition, since transcripts that are polyadenylated upstream of an in-frame stop codon are targeted for degradation (Frischmeyer et al., 2002), regulated FLC transcripts may simply not accumulate to detectable levels.

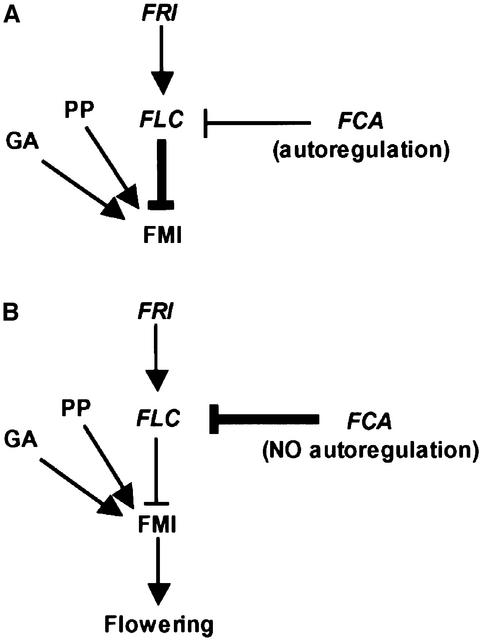

Removal of FCA negative autoregulation changed the interaction of the autonomous and FRI pathways. The antagonistic functions of FCA and FRI determine the levels of FLC mRNA in non-vernalized plants (Figure 9). Since flowering time is directly correlated with FLC levels, the balance of FRI/FCA activities is key to ensuring the correct timing of flowering. In wild-type winter annuals, FRI is epistatic to FCA function so FRI activity maintains high FLC mRNA levels, thus preventing flowering and causing plants to over-winter vegetatively (Figure 9A). Vernalization overcomes the FRI up-regulation of FLC resulting in flowering in spring. A change in epistasis between FRI and FCA, through removal of the negative autoregulation of FCA, changes the reproductive strategy of the plant, causing a shift from winter annual to rapid-cycling habit, namely flowering without the need for vernalization (Figure 9B). A winter annual habit is considered to be an adaptation to growth in different climates, for example being advantageous in localities with moderate winters and/or hot, dry summers. A requirement for this habit would therefore act as a strong selection for maintenance of FCA negative autoregulation. The main control of FLC expression in rapid-cycling accessions carrying loss-of-function fri alleles is the autonomous pathway. These accessions are adapted to environments where rapid flowering is beneficial. It is clear that mutations that affect the threshold at which FCA will autoregulate its expression will affect the available level of active FCA and hence the level of FLC mRNA. Natural variation in this autoregulation could therefore provide a mechanism by which FLC levels are controlled to facilitate adaptation to environment through regulated flowering time. The analysis of FCA autoregulation in natural Arabidopsis accessions varying in flowering time should be informative with respect to these selective forces. One rationale for characterizing the regulation of the autonomous pathway was to understand the molecular basis of cues that regulate flowering. This analysis reveals that the level of FCA limits flowering time in a manner effectively pre-set by FCA itself. This may constitute the molecular basis of an endogenous cue controlling flowering time. However, it will be interesting to investigate the influence of environmental cues on this regulation.

Fig. 9. Model of the interplay of flowering time control pathways. (A) FRI represses flowering in the absence of vernalization by up- regulating the floral repressor, FLC, which antagonizes the promotive effects of the photoperiod (PP) and gibberellin (GA) signal transduction pathways on the activation of floral meristem identity genes (FMI). (B) When FCA autoregulation is removed, increased FCA activity perturbs the quantitative interaction of these pathways. Increased FCA activity down-regulates FLC, enabling the FMI genes to respond to the promotive pathways and accelerate flowering. Promotive activities are denoted by arrowheads, repressive activities are denoted by T-bars.

We have discovered that the major mechanism controlling FCA expression is post-transcriptional autoregulation at the level of pre-mRNA processing, possibly through alternative polyadenylation. Although the consequences of alternative splicing and alternative polyadenylation on gene expression can be similar, we know relatively little about the mechanisms that underpin alternative polyadenylation. We have recently identified a mutant defective in FCA autoregulation at the level of poly(A) site choice. Therefore, in addition to unravelling the complexities of flowering time control, our characterization of the regulation of FCA expression may also provide a new genetically tractable means to study the molecular basis of alternative polyadenylation.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The mutants fca-1 and fca-4 were provided by M.Koornneef (Koornneef et al., 1991). The 35S::FCA-gene and the 35S::FCA-γ, 35S::FCA-δ, 35::cab-FCA-γ, PFCA::FCA-γ, PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS transgenic lines were as described in Macknight et al. (1997) and Macknight et al. (2002), respectively. Arabidopsis seeds were sown aseptically in Petri dishes containing GM medium as described in Macknight et al. (2002), stratified for 2 days at 4°C and planted in soil (mixture of Levingtons M3 compost with grit) at the four-leaf stage. Plants were grown in controlled environment rooms at 20°C under the conditions described in Macknight et al. (2002). Flowering time was measured by counting the number of rosette leaves at flowering.

RNA analysis

Three to 4 g of plant tissue from 2-week-old seedlings were ground in liquid nitrogen, and homogenized in NTES buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS). Total RNA was phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) (7.5:5 v/v) extracted, LiAcO and ethanol precipitated and resuspended in 200 µl of DEPC-treated water. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated from ∼400 µg of total RNA using oligo(dT) and streptavidin paramagnetic particles (Promega). Poly(A)+ RNA was ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 20 µl of DEPC-treated water and fractionated in formaldehyde–agarose containing gels. RNA was transferred to Hybond N+ nylon filters (Amersham) by conventional northern blotting.

The 5′ leader FCA probe was a 284 bp PCR-amplified DNA fragment (primers: forward 5′-AATTCATCATCTTCGATACTCG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGCTAGGGCTGCTTCCACG-3′), corresponding to nucleotides 22–306 of FCA DNA. To normalize loading, membranes were stripped in boiling 0.5% SDS and rehybridized with a β-TUBULIN coding region probe (Snustad et al., 1992). Blots were exposed to PhosphorImager screens (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunodetection of FCA protein

To isolate proteins, 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 1 ml Trizol (Gibco-BRL). Protein pellets were washed in guanidine hydrochloride (95% EtOH), EtOH 100% and resuspended in 100 µl of (8 M urea, 40 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) buffer. Approximately 20 µg of protein from each sample were resuspended in 2 vol. of SDS loading buffer (62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 2% w/v SDS, 10% v/v glycerol, 5% v/v 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 0.05% w/v bromophenol blue). The samples were boiled for 5 min and the insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was then separated on a denaturing 8% polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto Immobilon-PVDF membrane (Millipore). FCA polyclonal antibody (KL4) serum was used at a dilution of 1:1500 (v/v). The immunoreactive proteins were visualized using Pierce picosignal reagents, with the secondary antibody diluted 1:2000 (v/v), and by exposure to X-ray film (Amersham Hyperfilm) for 10 s to 5 min.

Transient subcellular localization

FCA:GUS fusion from PFCA::FCAto TGA:GUS (Macknight et al., 2002) was transferred to pMF6 by digestion with SalI and KpnI and cloning into pMF6 cut with XhoI and KpnI. Transient transfections of onion epidermal cells were performed as described previously (Varagona et al., 1992), except 10 µg of DNA was used to coat 2 mg of 1.6 µm gold particles. Nuclei were counter-stained for 10 min with 10 mg/ml DAPI.

Determination of GUS activity in transgenic lines

Histochemical GUS staining of transgenic Arabidopsis plants was performed as described in Jefferson et al. (1987). Seedlings grown in Petri dishes on GM medium were harvested from the plates at different time points and placed directly in 1 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide (X-gluc). Samples were incubated at 37°C overnight.

Molecular determination of the presence of fca-1 and fca-4 alleles and PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS transgene

The fca-1 allele was detected by PCR using the primers GSO344 (5′-AACCTCTTCACAGTCCACAGGG) and GSO345 (5′-TTGGCCGTA GATTAATGTTCAAAGG). After amplification, PCR products were digested with MseI (NEBL), which only cuts in the mutant allele producing 158 and 30 bp fragments.

To detect the fca-4 allele we used primers flanking the breakpoint in this allele. We designed a primer specific for the AT4g1550 gene (GS0505, 5′-GGTAGCAGCTTTATACAGTATGC-3′) and combined it with an FCA-specific primer (Fw4, 5′-ATGAGTTATCTTGCCC ATAAC-3′). A PCR product of the expected size (210 bp) was obtained only from fca-4 DNA.

To verify the presence of the PFCA::FCAto exon 5:GUS transgene, PCR amplifications were performed using FCA intron 3- (Fw3, 5′-GTT GAGTAGCTCTTATGTCTG-3′ and Fw4, 5′-ATGAGTTATCTTG CCCATAAC-3′) and GUS- (318, 5′-CACCAACGCTGATCAATTCC-3′)] specific primers. PCR fragments of the expected size, 1424 (Fw3 and 318) and 731 bp (Fw4 and 318) were obtained.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Ruth Bastow, Robert Sablowski, Ian Henderson and Louise Jones for comments on the manuscript. We thank Paul Jarvis for making FCA:GUS and Paul Dijkwel for jointly undertaking the nuclear localization experiments. V.Q. was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educacion y Cultura of Spain and an EU Marie Curie Fellowship. We acknowledge funding from a Core Strategic Grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and BBSRC grant 208/CAD05634.

References

- Boelens W.C., Jansen,E.J., van Venrooij,W.J., Stripecke,R., Mattaj,I.W. and Gunderson,S.I. (1993) The human U1 snRNP-specific U1A protein inhibits polyadenylation of its own pre-mRNA. Cell, 72, 881–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischmeyer P.A., van Hoof,A., O’Donnell,K., Guerrerio,A.L., Parker,R. and Dietz,H.C. (2002) An mRNA surveillance mechanism that eliminates transcripts lacking termination codons. Science, 295, 2258–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendall A.R., Levy,Y.Y., Wilson,A. and Dean,C. (2001) The VERNALIZATION 2 gene mediates the epigenetic regulation of vernalization in Arabidopsis. Cell, 107, 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson S.I., Beyer,K., Martin,G., Keller,W., Boelens,W.C. and Mattaj,L.W. (1994) The human U1A snRNP protein regulates polyadenylation via a direct interaction with poly(A) polymerase. Cell, 76, 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze M.W. and Kulozik,A.E. (1999) A perfect message: RNA surveillance and nonsense-mediated decay. Cell, 96, 307–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth S.R., Valverde,F., Ravenscroft,D., Mouradov,A. and Coupland,G. (2002) Antagonistic regulation of flowering-time gene SOC1 by CONSTANS and FLC via separate promoter motifs. EMBO J., 21, 4327–4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R.A., Kavanagh,T.A. and Bevan,M.W. (1987) GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J., 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson U., West,J., Lister,C., Michaels,S., Amasino,R. and Dean,C. (2000) Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science, 290, 344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., Hanhart,C.J. and Van der Veen,J.H. (1991) A genetic and physiological, analysis of late flowering mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Gen. Genet., 229, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., Alonso-Blanco,C., Peeters,A.J.M. and Soppe,W. (1998) Genetic control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol., 49, 345–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopato S., Kalyna,M., Dorner,S., Kobayashi,R., Krainer,A.R. and Barta,A. (1999) atSRp30, one of two SF2/ASF-like proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana, regulates splicing of specific plant genes. Genes Dev., 13, 987–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macknight R. et al. (1997) FCA, a gene controlling flowering time in Arabidopsis, encodes a protein containing RNA-binding domains. Cell, 89, 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macknight R., Duroux,M., Laurie,R., Dijkwel,P., Simpson,G. and Dean,C. (2002) Functional significance of the alternative transcript processing of the Arabidopsis floral promoter FCA. Plant Cell, 14, 877–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin M.E., Chandler,D., Somaiya,D., Dauwalder,B. and Mattox,W. (1998) Autoregulation of transformer-2 alternative splicing is necessary for normal male fertility in Drosophila. Genetics, 149, 1477–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels S.D. and Amasino,R.M. (1999) FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell, 11, 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels S.D. and Amasino,R.M. (2001) Loss of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity eliminates the late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and autonomous pathway mutations but not responsiveness to vernalization. Plant Cell, 13, 935–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouradov A., Cremer,F. and Coupland,G. (2002) Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell, 14, S111–S130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page T., Macknight,R., Yang,C.-H. and Dean,C. (1999) Genetic interactions of the Arabidopsis flowering time gene FCA, with genes regulating floral initiation. Plant J., 17, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon C.C., Burn,J.,E., Perez,P.P., Metzger,J., Edwards,J.A., Peacock,W.J. and Dennis,E.S. (1999) The FLF MADS box gene: a repressor of flowering in Arabidopsis regulated by vernalization and methylation. Plant Cell, 11, 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon C.C., Rouse,D.T., Finnegan,E.J., Peacock,W.J. and Dennis,E.S. (2000) The molecular basis of vernalization: the central role of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 3753–3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G.G. and Dean,C. (2002) Arabidopsis, the Rosetta stone of flowering time? Science, 296, 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G.G., Dijkwel,P.P., Quesada,V., Henderson,I. and Dean,C. (2003) FY is an RNA 3′-end processing factor that interacts with FCA to control the Arabidopsis floral transition. Cell, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Snustad D.P., Haas,N.A., Kopczak,S.D. and Silflow,C.D. (1992) The small genome of Arabidopsis contains at least nine expressed β-tubulin genes. Plant Cell, 4, 549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki Y., Seipelt,R.L., Peterson,M.L. and Manley,J.L. (1996) The polyadenylation factor Cst-64 regulates alternative processing of IgM heavy chain pre-mRNA during B cell differentiation. Cell, 87, 941–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varagona M.J., Schmidt,R.J. and Raikhel,N.V. (1992) Nuclear localization signal(s) required for nuclear targeting of the maize regulatory protein Opaque-2. Plant Cell, 4, 1213–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Hyman,L. and Moore,C. (1999) Formation of mRNA 3′ ends in eukaryotes: mechanism, regulation and interrelationships with other steps in mRNA synthesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 63, 405–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]