Abstract

Activation of platelets by exposed collagen after vessel wall injury is a primary event in the pathogenesis of stroke and myocardial infarction. Two collagen receptors, integrin α2β1 and glycoprotein VI (GPVI), are expressed at similar levels on human and mouse platelets, but their individual roles during collagen activation remain poorly defined. Recent genetic and pharmacologic experiments have revealed an essential role for GPVI but have failed to define the role of α2β1 or explain how two structurally distinct collagen receptors might function together to mediate platelet collagen responses. Discriminating the roles of these two collagen receptors is complicated by evidence suggesting that GPVI and platelet integrins may activate a common intracellular signaling pathway. To determine how α2β1 and GPVI activate platelets in response to collagen, we have (i) examined collagen signaling conferred by expression of these receptors in hematopoietic cell lines; (ii) determined the effect of blocking each receptor on the activation of human platelets by collagen; (iii) generated low-GPVI mice in which the α2β1/GPVI receptor ratio has been altered from 1:1 to 50:1 to expose α2β1 function; (iv) studied the collagen responses of mouse platelets lacking LAT, an adaptor protein critical for GPVI but not integrin signaling; and (v) addressed the mechanism by which soluble collagens activate wild-type platelets. These studies demonstrate that α2β1 requires inside-out signals to participate in collagen signaling and that α2β1 is required for collagen activation of platelets when GPVI signals are reduced by blocking anti-GPVI antibody, low receptor number, specific disruption of the GPVI signaling pathway, or forms of collagen that bind weakly to GPVI relative to α2β1. We propose a reciprocal two-receptor model of collagen signaling in platelets in which the nonintegrin receptor GPVI provides the primary collagen signal that activates and recruits the integrin receptor α2β1 to further amplify collagen signals and fully activate platelets through a common intracellular signaling pathway. This model explains many of the genetic and pharmacologic observations regarding collagen signaling in platelets and demonstrates a novel mechanism by which hematopoietic cells integrate signaling by structurally distinct receptors that share a common ligand.

Platelet activation in response to vessel wall injury is an initiating event in atherothrombotic diseases such as stroke and myocardial infarction (22). Collagen is a vessel wall protein known to directly activate platelets (38), and platelet activation by exposed collagen is believed to be an early and important step in the pathogenesis of these diseases. The molecular basis of platelet activation by collagen has been studied for more than 15 years with the identification of two major collagen receptors on mouse and human platelets: the integrin α2β1 (34) and glycoprotein VI (GPVI), a receptor homologous to immune receptors that signals through the transmembrane signaling adaptor Fc gamma receptor (FcRγ) (8). Identification of the roles of GPVI and α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets is essential for understanding the pathogenesis of stroke and myocardial infarction and for the development of new therapies to treat these diseases.

Previous pharmacologic and genetic studies to define the roles of α2β1 and GPVI during collagen activation of platelets have not yielded a clear picture of how these receptors work together to activate platelets in response to collagen. Early models proposed that collagen interaction with the high-affinity receptor α2β1 was required for subsequent interaction with GPVI (2), but we have shown that heterologous expression of GPVI alone at a receptor density equivalent to that in platelets is sufficient to confer collagen adhesion and signaling (6). Loss of GPVI expression in mouse and human platelets results in a complete loss of collagen activation of platelets (26, 27, 29), identifying a necessary role for GPVI but leaving that of α2β1 undefined. Early reports of human α2β1 deficiency states demonstrated bleeding disorders and platelets with severely reduced collagen responses (19, 30). In contrast, mouse platelets lacking α2β1 revealed almost no loss of aggregation responses to collagen (7, 11, 28). These studies are difficult to reconcile and may indicate important species differences, redundant receptor function, or a lack of participation by α2β1 in collagen signaling. The difficulty in distinguishing contributions by α2β1 and GPVI to collagen activation of platelets is compounded by their similar levels of expression on the platelet surface (6); by the possibility that the integrin α2β1, like the fibrinogen receptor αIIbβ3, requires inside-out activation for participation in collagen signaling (17); and by recent studies demonstrating that both receptors couple to the intracellular signaling proteins SYK, SLP-76, and PLCγ2 (10, 12, 32).

To define the roles of GPVI and α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets, we have combined several genetic and pharmacologic approaches. Heterologous expression of collagen receptors in hematopoietic cell lines expressing SYK, SLP-76, and PLCγ2 conferred collagen signaling that was entirely GPVI dependent and unaffected by coexpression of α2β1 unless the integrin was exogenously activated. Activated α2β1, however, contributed to collagen signals, suggesting that the inability of α2β1 alone to confer collagen signaling in cell lines may be due to a lack of integrin activation in these cells. To address the role of the two collagen receptors in human platelets, we used a novel blocking anti-GPVI antibody, 11A12, and the α2-blocking antibody 6F1 (9). Although 11A12 completely blocked collagen signaling conferred by GPVI in cell lines, neither antibody alone significantly blocked collagen activation of human platelets. Collagen activation could be completely blocked, however, by simultaneous exposure to both 11A12 and 6F1, a result that mirrors similar studies performed on mouse platelets (28) and reveals a role for both receptors that is conserved across species. To further expose the role of α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets, we generated mice in which the α2β1/GPVI ratio on platelets was altered from 1:1 to as high as 50:1 by reducing GPVI levels. Surprisingly, low-GPVI platelets lost responses to the high-affinity GPVI-specific agonists convulxin (CVX) and collagen-related peptide (CRP) but had relatively preserved collagen responses. Unlike those of wild-type platelets, however, the collagen responses of low-GPVI platelets were α2β1 dependent, demonstrating a direct role for α2β1 in platelet activation by collagen that is obscured by higher levels of GPVI. To determine whether α2β1 mediated collagen signaling directly through outside-in integrin signals or indirectly through augmentation of GPVI signals, we studied the collagen response of mouse platelets lacking the transmembrane adaptor LAT. LAT is a lipid raft-associated transmembrane adaptor critical for GPVI but not integrin signaling (15). Despite normal levels of surface GPVI, collagen signaling in LAT-deficient platelets was α2β1 dependent. Thus, reducing GPVI signaling from outside or inside the cell reveals a critical role for α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets.

Finally, we have addressed the mechanism by which soluble collagens activate platelets. As previously reported, commercially available soluble collagens activated wild-type platelets, albeit at much higher concentrations than required for fibrillar collagen (11, 28, 35). Like GPVI-blocked, low-GPVI, and LAT-deficient platelet responses to fibrillar collagen, wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagen were α2β1 dependent (11, 28, 35). Soluble collagens could not activate GPVI-deficient platelets, however, and soluble collagens supported adhesion of GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells. Soluble collagens therefore provide another means of reducing but not ablating GPVI signaling to reveal a critical role for α2β1.

Our studies support a model of collagen signaling in platelets in which two structurally distinct receptors regulate and amplify the response to exposed collagen in a reciprocal fashion. In this model GPVI is required to generate the first collagen signal that activates α2β1 which then amplifies collagen signals by using many of the same intracellular signaling effectors. This model resolves many outstanding questions regarding the activation of platelets by different forms of collagen as well as the collagen activation of platelets from genetically modified mice. Reciprocal signaling by integrin and nonintegrin collagen receptors reveals a novel mechanism of functionally integrating receptor signaling in hematopoietic cells and suggests that therapeutic approaches to human vascular diseases based on inhibiting platelet collagen responses must address the role of both collagen receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and animals.

CVX and CRP were from the same sources as described previously (6). Fibrillar type I collagen derived from equine tendon was obtained from Chronolog. Soluble collagens included rat tail type I collagen (Sigma), human placental type III collagen (Sigma), and human placental type I collagen (BD Biosciences). Anti-human GPVI mouse monoclonal antibodies were produced as previously described (6). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated AK-7, anti-human integrin α2 antibody, and anti-rat integrin α2 monoclonal antibody, Ha1/29, were purchased from Pharmingen. TS2/16, anti-human integrin β1 monoclonal antibody was from the American Type Culture Collection. Anti-human integrin α2 monoclonal antibody, 6F1, was a kind gift of Barry S. Coller. EMS16, a snake venom purified from Echis multisquamatus, was a kind gift of Cezary Marcinkiewicz. LAT-deficient mice were a kind gift of Larry Samelson. FcRγ-deficient mice were obtained as previously described (6), and BALB/c mice were used as wild-type mouse controls.

Generation of HEL cells and RBL-2H3 cells expressing GPVI and/or integrin α2, or GPVI-RIIa.

Stable clones of RBL-2H3 and HEL cells were obtained by using previously described methods (6).

Calcium signaling assays.

RBL-2H3 and HEL cells were labeled with Fura-2am (Molecular Probes), and calcium signaling was detected as previously described (6). Platelet calcium assays were performed in an identical manner, except that 10 μg of Fura-2am/ml was added to human platelet-rich plasma obtained as previously described (6).

Aggregation and adhesion assays.

Human and mouse platelet aggregation assays were performed as previously described (6). RBL-2H3 cell adhesion assays were performed as previously described (6).

Construction of the GPVI-RIIa chimeric gene.

Extracellular domain of human GPVI was amplified from a plasmid containing GPVI cDNA with the following primer pair: 5′-ATCGGATCCATTTGAGGAACCATGTCTCCATC-3′ and 5′-ATCCAAGCTTGGCGCGCCCTTGGTGTAGTACTGGCGG-3′. The amplified 0.8-kb fragment was subcloned into pBluescript KS(−) generating pBS-GPVI-0.8. The transmembrane domain and intracellular domain of FcγRIIa was amplified from a plasmid containing FcγRIIa cDNA with primer pairs (5′-ATCCACGCGTCCTCTTCACCAATGGGGATCATTGT-3′ and 5′-ATCCCTCGAGTCAATGGTGATGGTGATGATGAC-3′). The amplified 0.4-kb fragments was subcloned into pBS-GPVI-0.8 at AscI and XhoI sites, generating plasmid pBS-GPVI-RIIA. The final chimeric construct GPVI-RIIa consists of the extracellular domain of GPVI and the transmembrane and intracellular domain of FcγRIIa, and the correct construction was confirmed by sequencing.

Generation of GPVI-RIIa transgenic mice.

The BamHI/XhoI 1.2-kb fragments of GPVI-RIIa was cloned into a retroviral vector (MIGR1) at the XhoI and BglII sites. To drive platelet-specific expression of GPVI-RIIa, the 2.4-kb EcoNI/SalI fragments of MIGR1-GPVI-RIIa containing GPVI-RIIa and green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA flanking an internal ribosomal entry site sequence was blunt ended with Klenow, ligated with NotI linker, and subcloned into pNASS-Ibα.GFP at NotI sites. The resulting plasmid pIbα-GPVI-RIIa-GFP was digested with AscI and SphI to release a fragment containing GPIbα promoter sequences driving the expression of GPVI-RIIa and GFP. Transgenic animals were generated by using standard oocyte injection protocols by the Transgenic Core Facility in the University of Pennsylvania. The expression of GFP in founder mouse tail blood was detected by flow cytometry. Transgene-positive founder lines were bred onto an FcRγ-deficient mouse background.

Western blotting.

Mouse and human platelets were pelleted as described for the calcium signaling assay. Mouse and human platelet pellets were lysed in 1× sample buffer, and Western blotting was performed with the anti-GPVI monoclonal antibody 6B12 as previously described (6).

RESULTS

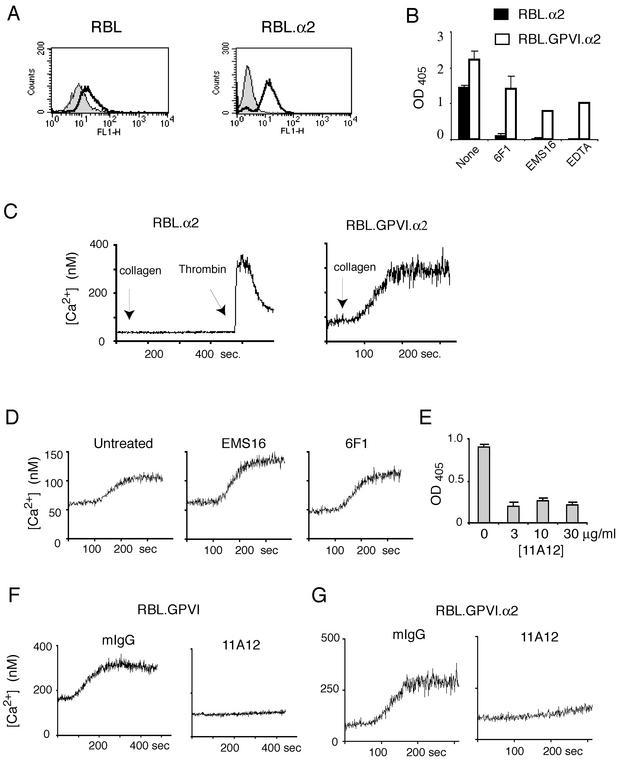

Expression of GPVI but not α2β1 confers collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells.

The RBL-2H3 cell line is a rat hematopoietic cell line that expresses the intracellular signaling proteins SYK, SLP-76, and PLCγ but is null for GPVI and expresses very low levels of the integrin α2 (Fig. 1A) (6, 20). We have previously shown that expression of GPVI in the RBL-2H3 cell line is sufficient to confer collagen signaling when GPVI receptor density matches that in human platelets (6). To determine whether expression of high levels of α2β1 alone was sufficient to confer collagen responses in these cells, we generated RBL-2H3 cells in which human α2 was expressed in association with rodent β1 (RBL.α2, Fig. 1A), a combination previously demonstrated to form a functional collagen receptor (42). To test whether expression of α2β1 augmented collagen responses in GPVI-expressing cells, we also generated RBL-2H3 cell lines that coexpressed human GPVI and α2 (RBL.GPVI.α2). Expression of α2β1 on RBL-2H3 cells conferred collagen adhesion under static conditions that could be blocked by the α2-blocking snake venom EMS-16 (23), by the anti-α2 antibody 6F1, or by the removal of cation with EDTA (Fig. 1B). As predicted by previous experiments performed with GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells (6), adhesion of RBL.GPVI.α2 cells to collagen was also directly mediated by GPVI and could only be partially blocked with anti-α2 blocking agents or with EDTA (Fig. 1B). Despite adhesion to collagen, no calcium signaling was detected in RBL.α2 cells in response to collagen, although RBL.GPVI.α2 cells exhibited robust calcium responses to collagen (Fig. 1C). To detect a contribution by α2β1 to collagen signaling in cells expressing both receptors, RBL.GPVI.α2 cells were exposed to EMS16 or 6F1 (Fig. 1D). Surprisingly, no effect on collagen signaling was noted with blockade of α2β1.

FIG. 1.

Expression of GPVI, but not integrin α2β1, confers collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells. (A) Expression of α2 integrin in wild-type (RBL) and α2-expressing (RBL.α2) RBL-2H3 cells. Endogenous rat α2 was measured by using the anti-rat α2 antibody Ha1/29 with secondary FITC-conjugated anti-hamster antibody in wild-type RBL-2H3 cells (left) and expressed human α2 measured by using FITC-conjugated anti-human antibody AK-7 in RBL.α2 cells (right). (B) Expression of α2 or GPVI confers static adhesion to collagen. RBL-2H3 cells expressing either integrin α2 (RBL.α2) or integrin α2 plus GPVI (RBL.GPVI.α2) were analyzed for adhesion to a collagen-coated plate for 30 min with or without 6F1 (10 μg/ml), EMS-16 (10 nM), or EDTA (5 mM). Note that the binding of RBL.α2 cells to collagen was cation dependent and inhibited by the anti-α2 agents 6F1 and EMS16. In contrast, the binding to collagen of RBL.GPVI.α2 cells was resistant to these treatments. (C) GPVI but not α2β1 confers collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells. RBL.α2 and RBL.GPVI.α2 cells were labeled with Fura-2 and intracellular calcium responses to collagen (10 μg/ml) or thrombin (10 nM) was measured. (D) Blockade of α2β1 does not reduce collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells expressing both GPVI and α2β1. RBL.GPVI.α2-mediated calcium signaling in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) was measured in untreated cells and in cells treated with high concentrations of EMS16 (500 nM) or 6F1 (100 μg/ml). (E) The anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 blocks GPVI-mediated collagen adhesion in RBL-2H3 cells. RBL-2H3 cells expressing high levels of GPVI (RBL.GPVI-173 [6]) were assayed for adhesion to collagen-coated plates for 15 min with or without pretreatment with 3, 10, or 30 μg of 11A12/ml. (F) Anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 blocks GPVI-mediated collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells. Calcium signals in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) were measured in RBL.GPVI-173 cells after treatment with 11A12 (20 μg/ml) or nonspecific mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (20 μg/ml). (G) Blockade of GPVI with 11A12 inhibits signaling in RBL-2H3 cells expressing both GPVI and α2β1. Calcium signals in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) were measured in RBL.GPVI.α2 cells after treatment with 11A12 (20 μg/ml) or nonspecific mouse IgG (20 μg/ml).

To confirm that collagen signals in RBL-2H3 cells were dependent upon GPVI-collagen interaction, a blocking anti-human GPVI monoclonal antibody, 11A12, was generated. The antibody 11A12 blocks both collagen adhesion and collagen signaling by GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells at low antibody concentrations (Fig. 1E and F). Like GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells, the collagen responses of RBL-2H3 cells expressing both GPVI and α2β1 were blocked by 11A12 (Fig. 1G). These experiments confirm that collagen signaling in RBL-2H3 cells is conferred by GPVI but not α2β1 even if both receptors are present.

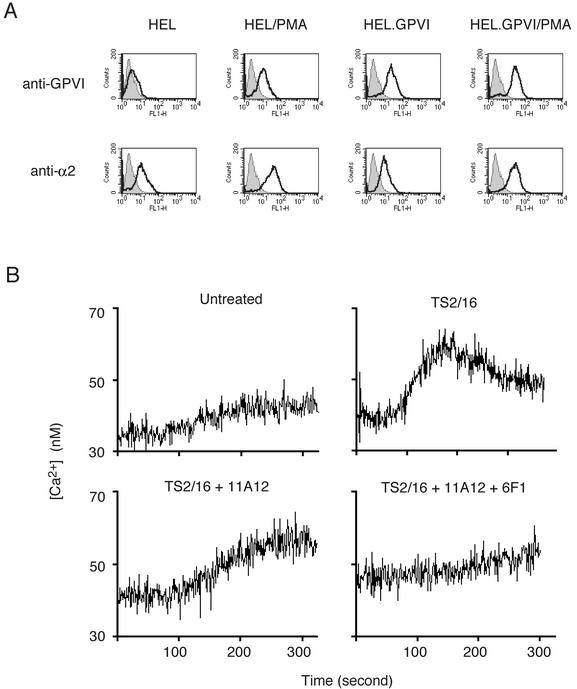

Exogenous activation of α2β1 confers collagen signals that are resistant to the anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 in HEL cells.

Platelet integrins are maintained in an inactive state and do not bind soluble ligand until they are activated by intracellular signals through a process known as inside-out signaling (31). Studies of the fibrinogen receptor αIIbβ3 in the megakaryocytic HEL cell line have revealed that these cells, unlike platelets, are unable to generate the inside-out signals required to activate this integrin (13). These studies suggested that the failure of RBL.α2 and RBL.GPVI.α2 to exhibit α2β1-dependent collagen signaling responses might be due to an inability to activate α2β1. To test the possibility that α2β1 requires activation to participate in collagen signaling, we used the human megakaryocytic HEL cell line and the TS2/16 antibody, an anti-human β1 antibody that, when bound to α2β1, increases the integrin's affinity for ligand (1). Unmanipulated HEL cells express low levels of α2β1 and GPVI that may be augmented by treatment with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (3, 4) (Fig. 2A). Neither unmanipulated nor PMA-treated HEL cells demonstrated collagen responses (data not shown). Since collagen responses in RBL-2H3 cells are highly dependent upon GPVI receptor density (6), we stably transfected HEL cells with a GPVI-expressing vector to further boost the level of GPVI (HEL.GPVI, Fig. 2A). When treated with PMA, HEL.GPVI cells generated small calcium signals in response to collagen but these could be significantly augmented by activating α2β1 with TS2/16 (Fig. 2B). Unlike collagen-responsive GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells, however, collagen signals in TS2/16-treated HEL.GPVI/PMA cells were resistant to the blocking anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 and could only be blocked with the blocking anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 and anti-α2 antibody 6F1. These results suggest that α2β1 may participate in collagen signaling responses in an activation-dependent manner. By extension, the failure to confer signaling in RBL-2H3 cells with expression of α2β1 is likely to be due to an inability to activate the integrin.

FIG. 2.

The integrin α2β1 participates in collagen responses in HEL cells in an activation-dependent manner. (A) Generation of HEL cells expressing high levels of GPVI and α2β1. To generate HEL cells expressing high levels of the collagen receptors GPVI and α2β1, unmanipulated or GPVI-transfected cells were matured with PMA treatment. GPVI and α2 surface expression was detected by using FITC-11A12 and FITC-AK-7, respectively. HEL, unmanipulated HEL cells; HEL/PMA, PMA-treated HEL cells; HEL.GPVI, HEL cells in which human GPVI is stably expressed through a transgene; HEL.GPVI/PMA, HEL.GPVI treated with PMA. (B) α2β1 contributes to collagen signaling in HEL cells after exogenous activation. Calcium signaling in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) was measured in HEL.GPVI/PMA cells untreated or pretreated with the activating anti-β1 antibody TS2/16 (50 μg/ml, top panels). Calcium signals in TS2/16-treated HEL.GPVI/PMA cells in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) were also measured in the presence of the blocking anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 (30 μg/ml) with or without the blocking anti-α2 antibody 6F1 (30 μg/ml, lower panels). Note that the inhibition of collagen signaling conferred by TS2/16 treatment requires blockade of α2β1 in addition to GPVI.

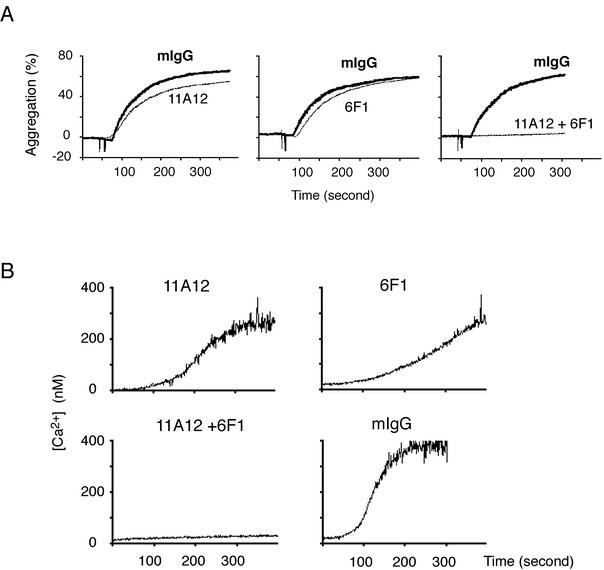

Blockade of both α2β1 and GPVI is required to inhibit collagen activation of human platelets.

Augmentation of collagen signaling by exogenously activated α2β1 in HEL cells suggested that in platelets both receptors are likely to participate in collagen signaling. To test the role of each receptor for collagen activation of human platelets, aggregation studies were performed with blocking antibodies against α2, GPVI, or both. At higher concentrations of collagen (>10 μg/ml) very little inhibition was seen with blockade of either α2β1 or GPVI alone, but virtually complete, synergistic inhibition was observed with simultaneous blockade of the two receptors (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained through analysis of calcium signaling induced by collagen, although small reductions in calcium flux are detectable with inhibition of each receptor alone (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with those obtained in the HEL cell system with activated α2β1 and demonstrate the participation of both receptors during collagen activation of platelets.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of collagen activation of human platelets requires blockade of both GPVI and α2β1. (A) Inhibition of collagen-induced platelet aggregation requires treatment with both the anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 and the anti-α2 antibody 6F1. Gel-filtered human platelets (2 × 108/ml) were treated with 30 μg of 11A12/ml, 30 μg of 6F1/ml, or both for 5 min prior to measuring platelet aggregation in response to 30 μg of collagen/ml. Similar results were obtained by using 10 and 100 μg of collagen/ml (data not shown). (B) Inhibition of collagen-induced calcium signaling requires both the anti-GPVI antibody 11A12 and the anti-α2 antibody 6F1. Calcium signaling in response to collagen (10 μg/ml) was measured by using the same antibody conditions as in panel A. Note the synergistic inhibitory effect of blocking both GPVI and α2β1 on platelet activation by collagen.

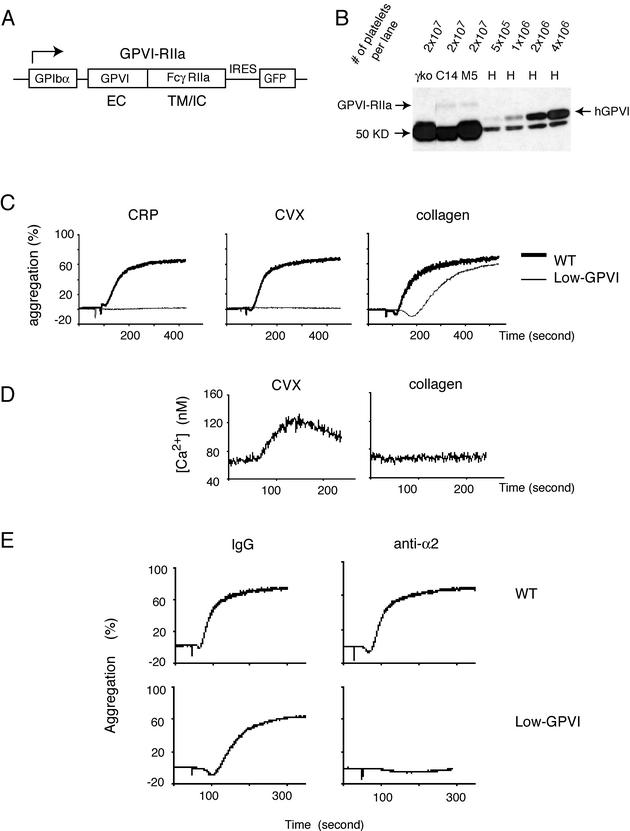

Low-GPVI platelets signal in response to collagen but not the GPVI-specific agonists CVX or CRP.

Although our experiments supported a significant role for α2β1 during collagen activation of human platelets, both mouse and human GPVI-deficient platelets are unresponsive to collagen (26, 27), and α2β1-deficient platelets have near-normal collagen responses (11, 28). Given the requirement for α2β1 activation observed in HEL cells, we hypothesized that during collagen stimulation α2β1 might require GPVI for inside-out activation and, once activated, perform a signaling function redundant with that of GPVI. To expose such a role for α2β1 during collagen signaling in platelets, we generated mice with altered collagen receptor stoichiometries such that the GPVI/α2β1 ratio was radically skewed in favor of α2β1. Since GPVI expression requires coexpression of the FcRγ chain, FcRγ-deficient mouse platelets lack surface GPVI and are completely unresponsive to collagen (27). It is not currently known whether mouse platelets express FcRγ partners other than GPVI. To generate low-GPVI platelets without rescuing other FcRγ partners, we therefore engineered transgenic mice expressing a GPVI-FcγRIIa chimera (GPVI-RIIa) under control of the GPIbα promoter and crossed these transgenics onto an FcRγ-deficient background (Fig. 4A). The GPVI-RIIa chimeric receptor contains the extracellular domain of human GPVI and the transmembrane and intracellular domains of the human platelet Fc receptor FcγRIIa. FcγRIIa is known to signal through the same intracellular signaling pathway as GPVI-FcRγ and is expressed independently of FcRγ in human but not mouse platelets (5, 24). Using this strategy we generated two lines of mice, M5 and C14, whose platelets express levels of GPVI-RIIa that are ca. 2% that of GPVI on normal human platelets and that we designate “low-GPVI” platelets (Fig. 4B). Although only results obtained by using M5-derived low-GPVI platelets are shown, M5 and C14 platelets exhibited identical responses to CVX, CRP, and collagen (data not shown). Low-GPVI platelets express wild-type levels of α2β1 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Integrin α2β1 is required for collagen responses in low-GPVI mouse platelets. (A) Schematic of the GPVI-RIIa transgene used to generate mice with low-GPVI platelets. GPIbα, the GPIbα promoter; EC, human GPVI extracellular domain; TM/IC, FcγRIIa transmembrane and intracellular domains; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site. (B) Low-GPVI platelets express GPVI-RIIa at a level equal to ca. 2% of the GPVI on human platelets. To generate low-GPVI platelets, two GPVI-RIIa transgenic founder lines, M5 and C14, were bred onto an FcRγ-deficient background to eliminate native GPVI. The expression level of GPVI-RIIa in these two lines was measured by Western blotting with an antibody that recognizes the extracellular domain of human GPVI (clone 6B12) and compared to that of human platelet lysates from various numbers of platelets. Note the increased size of GPVI-RIIa relative to wild-type human GPVI due to the presence of the longer FcγRIIa intracellular tail. The 50-kDa band detected in both wild-type human and transgenic mouse platelets is also detected in FcRγ-deficient platelets that lack GPVI and is a background band. (C) Low-GPVI platelets respond to collagen but not to the GPVI-specific agonists CVX or CRP. The aggregation responses of low-GPVI (GPVI-RIIa+/+; FcRγ−/−) and wild-type platelets (3 × 108/ml) to CVX (10 nM), CRP (150 μg/ml), and collagen (30 μg/ml) are shown. Each experiment is representative of three to five experiments with similar results. (D) The GPVI-RIIa receptor is efficiently activated by CVX but not collagen in RBL-2H3 cells. GPVI-RIIa-expressing RBL-2H3 cells were tested for calcium signaling in response to CVX (10 nM) or collagen (10 μg/ml). Note that GPVI-RIIa responds preferentially to the high-affinity GPVI ligand CVX. (E) Low-GPVI but not wild-type platelet collagen responses are dependent upon α2β1. Low-GPVI and wild-type platelets were pretreated with the blocking anti-α2 antibody Ha1/29 (10 μg/ml) or control IgG (10 μg/ml) prior to stimulation with collagen (30 μg/ml). This experiment is representative of three experiments with similar results.

Unlike wild-type platelets, low-GPVI platelets exhibited no aggregation response to the high-affinity GPVI ligands CVX or CRP (Fig. 4C). Remarkably, despite a virtually complete loss of GPVI-specific responses, low-GPVI platelets had relatively preserved collagen responses (Fig. 4C). Low-GPVI platelets did exhibit a right shift in their collagen dose response that was in proportion to the level of GPVI-RIIa receptors expressed (Fig. 4C and data not shown). To rule out the possibility that collagen might be a more potent agonist for the GPVI-RIIa chimeric receptor than for wild-type GPVI, we characterized the responses of GPVI-RIIa to collagen and CVX in GPVI-RIIa-expressing RBL-2H3 cells. As previously reported for GPVI (6), expression of GPVI-RIIa at modest levels in RBL-2H3 cells conferred signaling responses to the high-affinity GPVI ligand CVX but not to collagen (Fig. 4D). Thus, preferential preservation of collagen responses in low-GPVI platelets is not due to a difference in ligand preference between GPVI and GPVI-RIIa receptors.

Collagen activation of low-GPVI platelets is mediated by α2β1.

Signaling in response to collagen but not GPVI-specific agonists in low-GPVI platelets is consistent with the function of a second receptor that recognizes collagen but not CVX or CRP. To determine whether α2β1 is responsible for collagen signaling in low-GPVI platelets, we compared the sensitivity of wild-type and low-GPVI platelets to α2β1 blockade with the blocking anti-α2 monoclonal antibody Ha1/29 (25). As observed in human platelets (Fig. 3A), blockade of α2β1 in wild-type mouse platelets results only in a slightly delayed aggregation response to collagen (Fig. 4E). In contrast, blockade of α2β1 completely blocked low-GPVI platelet responses to collagen (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, analysis of a third transgenic line whose platelets express levels of GPVI-RIIa that are ca. 10% that of GPVI on normal human platelets revealed an intermediate phenotype in which inhibition of α2β1 significantly reduced but did not ablate platelet collagen responses (data not shown). These results demonstrate that collagen responses in low-GPVI platelets are mediated by the integrin α2β1 and suggest that as GPVI levels increase the role of α2β1 becomes increasingly redundant.

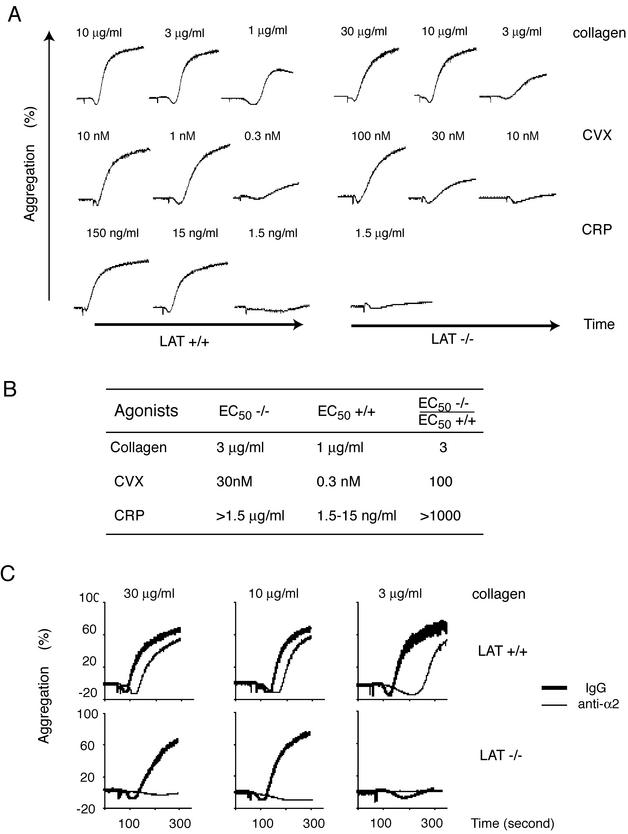

Despite normal levels of GPVI, collagen activation of LAT-deficient platelets also requires α2β1.

The ability to activate low-GPVI platelets with collagen but not CVX or CRP mirrors the response of platelets lacking the transmembrane adaptor LAT (15). As previously reported, LAT-deficient platelets exhibit only a mild reduction in platelet collagen responses but a profound reduction in the response to the GPVI-specific agonists CVX and CRP (Fig. 5A). A comparison of the dose-response curves of wild-type and LAT-deficient platelet aggregation reveals a 3-fold rightward shift for collagen and 100- and 1,000-fold rightward shifts for CVX and CRP, respectively (Fig. 5B). To determine whether the collagen responses of LAT-deficient platelets are α2β1 dependent, we tested the effect of the blocking anti-α2 antibody Ha1/29. Like low-GPVI platelets, even strong LAT-deficient platelet responses to collagen were virtually ablated by α2β1 inhibition (Fig. 5C). The requirement for α2β1 is not related to a reduction in GPVI receptor number since the surface expression of GPVI and α2β1 receptors on LAT-deficient platelets was indistinguishable from that on wild-type platelets (data not shown). These results demonstrate that reducing GPVI signaling in platelets from outside the cell by lowering the receptor number or from inside the cell by impairing GPVI signaling reveals a critical role for α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets.

FIG. 5.

α2β1 is required for collagen responses in LAT-deficient mouse platelets. (A) Aggregation dose-responses of wild-type and LAT-deficient platelets to collagen and the GPVI-specific agonists CVX and CRP. Gel-filtered platelets from wild-type (LAT+/+) and LAT-deficient (LAT−/−) platelets were exposed to various concentrations of collagen, CVX, and CRP, and platelet aggregation was measured. Note the small right shift observed in LAT-deficient platelets in response to collagen compared to the large right shifts observed for CVX and CRP. This experiment is representative of 3 experiments with similar results. (B) The 50% effective concentration (EC50) of platelet aggregation responses of wild-type (+/+) and LAT-deficient (−/−) platelets. The EC50s were calculated based on the aggregation responses to collagen, CVX, and CRP shown in panel A. Note that the increases in EC50 for LAT-deficient platelet responses to the GPVI-specific agonists CVX and CRP vastly exceed that for collagen. (C) Collagen responses of LAT-deficient platelets require α2β1. Wild-type (LAT+/+) and LAT-deficient (LAT−/−) platelets were pretreated with 30 μg of the blocking anti-α2 antibody Ha1/29 or IgG control/ml, and the response to various concentrations of collagen was measured. Note that even strong responses of LAT-deficient platelets to collagen are ablated by inhibition of α2β1, whereas wild-type platelets exhibit only a slight delay in the aggregation response.

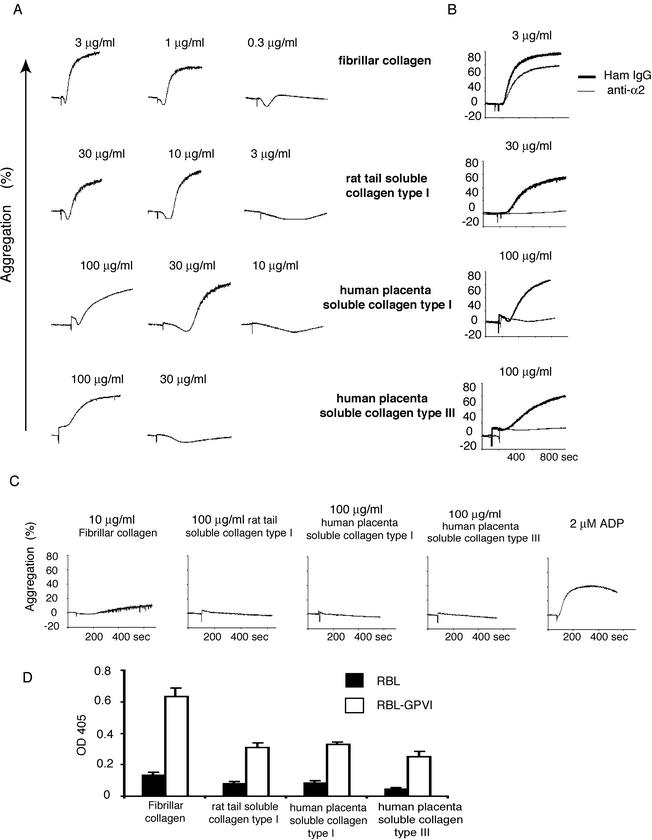

Activation of wild-type platelets by soluble collagens is α2β1 dependent but soluble collagens interact with GPVI.

The partial digestion of fibrillar type I and type III collagen yields more soluble forms of collagen that have been reported to bind preferentially to α2β1 and not GPVI (11, 16, 17, 28, 35), suggesting that these forms of collagen might activate wild-type platelets in a manner analogous to the activation of low-GPVI and LAT-deficient platelets by fibrillar collagen. As previously reported (11, 28, 35), two commercially available forms of soluble type I collagen (derived from rat tail and human placenta) and a soluble type III collagen (derived from human placenta) stimulate aggregation of wild-type mouse platelets but do so much less efficiently than fibrillar collagen (Fig. 6A). Thus, wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagens are right shifted in a manner similar to that of low-GPVI and LAT-deficient platelet responses to fibrillar collagen. Like low-GPVI and LAT-deficient platelet responses to fibrillar collagen, wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagens are sensitive to blockade by the anti-α2 antibody (Fig. 6B) (11, 28, 35). However, both fibrillar and soluble collagen aggregation responses are lost in FcRγ-deficient or GPVI-blocked platelets (Fig. 6C) (11, 28), suggesting that some residual interaction with GPVI is required for soluble collagen to activate platelets. To test whether soluble collagens can interact with GPVI, we performed static adhesion assays with wild-type and GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells. Expression of GPVI conferred adhesion to soluble collagens, although adhesion was weaker than that obtained with more fibrillar collagen (Fig. 6D). These results demonstrate that although activation of platelets by soluble type I and type III collagens requires α2β1, soluble collagens can bind GPVI weakly, and GPVI is required for activation of platelets by soluble collagens.

FIG. 6.

Wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagens are α2β1-dependent but soluble collagens interact with GPVI. (A) Aggregation responses of wild-type platelets to fibrillar and soluble collagens. Aggregation dose-responses of wild-type mouse platelets to two forms of soluble type I collagen (derived from rat tail and human placenta) and one form of soluble type III collagen (derived from human placenta) are shown in comparison to fibrillar type I collagen. Note that wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagens are right shifted up to 100-fold. (B) Aggregation responses of wild-type platelets to soluble but not fibrillar collagen require α2β1. The effects of the blocking anti-α2 antibody Ha1/29 (anti-α2) and nonspecific hamster IgG (Ham IgG) on the response of wild-type platelets to three forms of soluble collagen and to type I fibrillar collagen are shown. Note that wild-type platelet responses to soluble collagens but not fibrillar collagen require α2β1. Similar results were obtained with human platelets and the 6F1 antibody (data not shown). (C) Activation of platelets by soluble and fibrillar collagens requires GPVI-FcRγ. FcRγ-deficient platelet responses to activating concentrations of fibrillar and soluble collagens are shown in comparison to the G protein-coupled receptor agonist ADP. Note that soluble collagen responses require GPVI as well as α2β1. (D) GPVI mediates adhesion to type I and III soluble collagens. Wild-type RBL-2H3 cells and RBL-2H3 cells expressing GPVI (RBL.GPVI) were analyzed for adhesion to plates coated with fibrillar type I collagen or soluble type I and III collagens. Note that expression of GPVI confers adhesion to soluble collagen as well as to fibrillar collagen, but to a lesser extent.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of human and mouse platelets have yielded a complex picture of the platelet response to collagen. Two important collagen receptors, integrin α2β1 and GPVI, have been identified, but whether and how they function together during collagen activation of platelets has been unclear. In the present study we utilized a number of methods, including heterologous expression in cell lines, blocking monoclonal antibodies, genetic experiments in mice, and different forms of collagen to define the function of each receptor. Our results support a unique two-receptor system in which integrin and nonintegrin collagen receptors function in a reciprocal manner to activate platelets in response to collagen.

Our studies address two outstanding issues regarding collagen activation of platelets: the sufficient roles of GPVI and α2β1 and whether platelet collagen receptors function independently or in an integrated manner. Analysis of collagen receptor-expressing RBL-2H3 cells demonstrates that GPVI but not α2β1 is sufficient to confer collagen signaling, a result consistent with the preservation of collagen responses in α2β1-deficient but not GPVI-deficient mouse platelets (7, 11, 27, 28). The inability of α2β1 to confer collagen signaling and the complete loss of collagen signaling observed in GPVI-deficient platelets may indicate that α2β1 functions only as an adhesive receptor for collagen. Alternatively, α2β1 may require inside-out activation to participate in collagen signaling, a process that may be deficient in RBL-2H3 cells (13) and in which GPVI might be required to generate the activating signal in an experimental system in which collagen was the sole agonist present. To expose an inside-out signaling defect in cell lines, we exogenously activated α2β1 by using the TS2/16 antibody in HEL cells that express both α2β1 and GPVI. TS2/16-mediated α2β1 activation generated collagen signals that, in contrast to those in untreated cells, could not be inhibited by a blocking anti-GPVI antibody. These studies support previous work demonstrating an increase in the binding of soluble collagen (a relatively specific α2β1 ligand, discussed further below) after platelet activation (17) and suggest that α2β1 participates directly in collagen signaling in an activation-dependent manner.

If GPVI alone is sufficient for collagen signaling and α2β1 requires inside-out activation signals generated by GPVI to participate in collagen signaling, the role of α2β1 might only be exposed by drastically reducing but not ablating GPVI signals. To reduce but not eliminate GPVI signaling in platelets, we used four approaches: (i) pharmacologic inhibition of GPVI with a blocking anti-GPVI antibody; (ii) generation of mice with platelets expressing very low levels of GPVI; (iii) selective interruption of GPVI but not integrin signaling with platelets lacking LAT, a lipid raft-associated transmembrane adaptor; and (iv) activation of wild-type platelets by soluble collagens that are relatively but not absolutely specific ligands for α2β1. Remarkably, although these approaches reduce GPVI signaling in distinct ways from both outside and inside the cell, they result in virtually identical phenotypes: severe loss of platelet responses to GPVI-specific agonists but relatively preserved platelet collagen responses that are dependent upon α2β1 function.

Inhibition of human platelet collagen responses required blockade of both GPVI and α2β1, a result identical to that observed with blocking anti-mouse GPVI and anti-mouse α2 antibodies (28, 36). The inability of anti-GPVI antibodies to completely block platelet collagen responses in both species is most likely due to the fact that pharmacologic inhibition, unlike genetic ablation, is not absolute. GPVI-blocked platelets therefore retain enough GPVI signaling to activate α2β1, which then supports collagen responses unless it is simultaneously blocked. These results reveal a significant role for α2β1 during collagen activation of platelets and suggest that pharmacologic approaches designed to inhibit these responses may require blockade of both integrin and nonintegrin receptors. These results also provide evidence for the conservation of collagen receptor function across species and suggest that there is no need to postulate the existence of two distinct GPVI-binding sites for collagen to explain prior results with blocking anti-GPVI antibodies (36).

To genetically expose the role of α2β1, we generated mice with platelets in which the α2β1/GPVI receptor ratio is shifted radically in favor of α2β1, while retaining a small number of GPVI receptors to provide inside-out signals for α2β1 activation during collagen exposure (these are referred to here as low-GPVI platelets). Low-GPVI platelets expressing as few as 30 to 40 receptors per platelet (6) exhibited relatively preserved aggregation responses to collagen despite the loss of aggregation responses to the high-affinity GPVI-specific ligands CVX or CRP. Unlike wild-type, but similar to GPVI-blocked human platelets, low-GPVI platelet collagen responses were α2β1 dependent, a result supported by a recent study of platelets with a less drastic reduction in GPVI receptor density (37). Thus, reducing GPVI-mediated collagen signals either through pharmacologic blockade or through genetic reduction in receptor number results in collagen signals that are supported by the integrin α2β1.

How does α2β1 support collagen responses in GPVI-blocked and low-GPVI platelets? α2β1-dependent signals may be explained either through a direct and/or an indirect mechanism. In a direct mechanism, activated α2β1 binds collagen and generates independent outside-in signals that are sufficient to fully activate platelets. In an indirect mechanism, activated α2β1 functions as a coreceptor to enhance signaling through GPVI or an unidentified collagen receptor. To distinguish between direct α2β1-mediated signaling and indirect α2β1-mediated augmentation of GPVI signaling, we studied platelets lacking LAT, a lipid raft-associated transmembrane adaptor critical for GPVI but not integrin signal transduction.

Recent studies of integrin outside-in signaling in platelets have revealed that both the integrin receptor for fibrinogen (αIIbβ3) and GPVI-FcRγ signal through the non-receptor tyrosine kinase SYK (40), the adaptor SLP-76 (14), and the phospholipase PLCγ2 (39). Recent studies of platelet spreading on the α2β1-specific peptide ligand GFOGER suggest that α2β1 also utilizes these signaling molecules during outside-in signaling (12). Thus, platelets lacking SYK, SLP-76, or PLCγ2 are deficient in both fibrinogen spreading and activation by GPVI-specific agonists in addition to being unresponsive to collagen. In contrast, LAT-deficient platelets exhibit an almost complete loss of signaling responses to the GPVI-specific ligands CVX and CRP but spread normally on fibrinogen (Fig. 5) (15, 33). Thus, the transmembrane adaptor LAT is a signaling protein utilized preferentially by GPVI-FcRγ but not by integrins in platelets. This is consistent with studies demonstrating that during collagen stimulation of platelets GPVI but not α2β1 associates with lipid rafts (21, 39; data not shown), where LAT is exclusively localized (41). It is also consistent with the observation that intracellular signaling responses to collagen in GPVI-blocked platelets are identical to those in untreated platelets except for a nearly complete lack of LAT phosphorylation (36). Thus, our finding that LAT-deficient platelet collagen responses are mediated by α2β1 despite normal levels of surface GPVI is most consistent with direct activation of platelets by α2β1 outside-in signals.

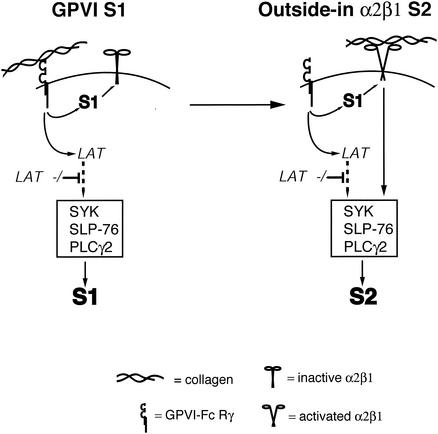

Our studies support a model of collagen signaling in platelets in which an integrin and a nonintegrin receptor function in a reciprocal fashion to generate common activating intracellular signals in response to a common ligand (Fig. 7). In this model, the nonintegrin receptor GPVI is required to generate the first signal, S1, which engages the integrin α2β1 through inside-out activation. In the setting of high GPVI receptor density, unlimited access to collagen, and unimpaired GPVI signaling, GPVI-mediated signals are sufficient to fully activate platelets. However, when the GPVI S1 is reduced by GPVI receptor blockade, low GPVI receptor density, or impaired GPVI signaling, the integrin α2β1 is required to generate subsequent signals, S2, for full platelet activation. Significantly, this model does not exclude an α2β1 coreceptor function by which it might also augment GPVI-mediated signals. However, coreceptor function alone cannot explain the requirement for α2β1 in LAT-deficient platelets where GPVI is expressed at a high level. This model fits the accumulated cellular and genetic data regarding collagen activation of platelets: (i) platelets lacking GPVI or FcRγ have lost the ability to activate α2β1 in response to collagen and therefore cannot respond to collagen despite normal α2β1 expression; (ii) α2β1-deficient platelets express high enough levels of GPVI to make α2β1 unnecessary for collagen signaling under experimental conditions using collagen suspensions; (iii) SYK, SLP-76, and PLCγ2 are required for signaling downstream of both collagen receptors; and (iv) LAT-deficient platelets have lost most but not all GPVI signaling and thus are able to activate α2β1 and generate α2β1-dependent signals. Since the reports of α2β1-deficient human individuals with reduced platelet collagen responses preceded the ability to measure GPVI levels (19, 30), it is tempting to speculate that these individuals may have also had reduced GPVI function.

FIG. 7.

Reciprocal model of collagen signaling by GPVI and integrin α2β1 in platelets. A proposed model of collagen signaling mediated by GPVI and integrin α2β1 is shown. GPVI is postulated to provide the first collagen signal, S1, that mediates inside-out activation of α2β1. In the presence of normal levels of GPVI, large amounts of collagen and LAT, the GPVI-derived S1 is sufficient for platelet activation by fibrillar collagen. Activated α2β1 is postulated to generate a second collagen signal, S2, that is LAT independent and sufficient to activate platelets. α2β1-generated signals are proposed to be required when GPVI signaling is low, e.g., due to antibody blockade, low receptor expression, loss of LAT, or exposure to soluble collagens that bind preferentially to α2β1. Both GPVI and α2β1 are believed to activate SYK, SLP-76, and PLCγ2. The position of LAT is meant to demonstrate its critical role downstream of GPVI but not α2β1 rather than to indicate that it lies upstream of SYK or SLP-76.

Our model predicts that a pure α2β1 ligand would be unable to independently bind or activate resting platelets due to an inability to generate the signal required to activate the integrin (i.e., S1). Soluble collagens, generated by partial enzymatic digestion of fibrillar type I or type III collagen to a form lacking the complete quaternary structure of native banded collagen, have been described as such a ligand (11, 16, 17, 28, 35). Significantly, type III collagen that has been highly purified to remove all traces of fibrillar collagen has been demonstrated to behave as an α2β1-selective ligand and bind platelets only after exogenous activation of the α2β1 integrin with TS2/16 antibody or endogenous activation by other platelet receptors (16, 17). In contrast, other forms of soluble collagen have been reported to mediate platelet adhesion and activation independently but require α2β1 to do so (Fig. 6) (11, 28, 35). A straightforward explanation for these observations is that forms of soluble collagen capable of activating platelets retain a small amount of GPVI interaction that is sufficient to activate α2β1. This mechanism is supported by the observation that soluble collagens require GPVI to activate platelets (Fig. 6C) (11, 28) and by the ability of soluble collagens to support adhesion of GPVI-expressing RBL-2H3 cells (Fig. 6D). Thus, platelet responses to soluble collagens can be explained on the basis of a severe but not absolute loss of GPVI activation with retention of α2β1 interaction, resulting in platelet responses that phenocopy those of GPVI-blocked, low-GPVI, and LAT-deficient platelets to fibrillar collagen. The use of a soluble-type collagen also provides a logical explanation for the results of a study of collagen signaling in platelets performed prior to the molecular identification of GPVI that demonstrated α2β1-dependent signaling mediated by Syk and PLCγ2 (18). A model of reciprocal signaling by GPVI and α2β1 therefore provides an explanation for the collagen responses observed both with platelets from genetically engineered mice and wild-type platelets with different forms of collagen.

The development of a dual receptor system in which integrin and nonintegrin receptors respond reciprocally to a common ligand suggests that each receptor contributes a specialized component of the platelet response to exposed collagen. Since GPVI responses to collagen are highly dependent upon receptor density (6), it is possible that GPVI-collagen interactions regulate the primary, graded signaling responses to vessel injury, whereas α2β1 mediates rapid secondary adhesive and signaling responses once a threshold level of GPVI-collagen interaction has been reached. Since platelet-collagen interactions are believed to participate in primary platelet adhesion and activation events in the setting of flowing blood, such a system might have evolved to allow platelets to respond differentially but with adequate speed to varying degrees of vascular disruption and collagen exposure. Further testing of this model will provide greater insight into the role of integrin signaling during platelet activation and facilitate the development of novel therapeutic agents designed to block or slow the platelet collagen response in the setting of vascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cezary Marcinkiewicz for providing EMS16, Barry Coller for providing 6F1 antibody, Skip Brass and Ed Morrisey for thoughtful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, Larry Samelson for LAT-deficient mice, and Ying Liu and Ke Lu for valuable assistance with mouse husbandry and genotyping.

This work was supported by grants from the NHLBI (H.C. and M.L.K.), the AHA (M.L.K.), and the W. W. Smith Charitable Trust (M.L.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alon, R., P. D. Kassner, M. W. Carr, E. B. Finger, M. E. Hemler, and T. A. Springer. 1995. The integrin VLA-4 supports tethering and rolling in flow on VCAM-1. J. Cell Biol. 128:1243-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes, M. J., C. G. Knight, and R. W. Farndale. 1998. The collagen-platelet interaction. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 5:314-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlanga, O., R. Bobe, M. Becker, G. Murphy, M. Leduc, C. Bon, F. A. Barry, J. M. Gibbins, P. Garcia, J. Frampton, and S. P. Watson. 2000. Expression of the collagen receptor glycoprotein VI during megakaryocyte differentiation. Blood 96:2740-2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger, S. R., M. M. Zutter, S. Sturgill-Koszycki, and S. A. Santoro. 1992. Induced cell surface expression of functional α2β1 integrin during megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 leukemic cells. Exp. Cell Res. 202:28-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chacko, G. W., A. M. Duchemin, K. M. Coggeshall, J. M. Osborne, J. T. Brandt, and C. L. Anderson. 1994. Clustering of the platelet Fc gamma receptor induces noncovalent association with the tyrosine kinase p72syk. J. Biol. Chem. 269:32435-32440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, H., D. Locke, Y. Liu, C. Liu, and M. L. Kahn. 2002. The platelet receptor GPVI mediates both adhesion and signaling responses to collagen in a receptor density-dependent fashion. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3011-3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, J., T. G. Diacovo, D. G. Grenache, S. A. Santoro, and M. M. Zutter. 2002. The α2 integrin subunit-deficient mouse: a multifaceted phenotype including defects of branching morphogenesis and hemostasis. Am. J. Pathol. 161:337-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemetson, J. M., J. Polgar, E. Magnenat, T. N. Wells, and K. J. Clemetson. 1999. The platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily closely related to FcαR and the natural killer receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29019-29024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coller, B. S., J. H. Beer, L. E. Scudder, and M. H. Steinberg. 1989. Collagen-platelet interactions: evidence for a direct interaction of collagen with platelet GPIa/IIa and an indirect interaction with platelet GPIIb/IIIa mediated by adhesive proteins. Blood 74:182-192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao, J., K. E. Zoller, M. H. Ginsberg, J. S. Brugge, and S. J. Shattil. 1997. Regulation of the pp72syk protein tyrosine kinase by platelet integrin αIIbβ3. EMBO J. 16:6414-6425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtkotter, O., B. Nieswandt, N. Smyth, W. Muller, M. Hafner, V. Schulte, T. Krieg, and B. Eckes. 2002. Integrin α2-deficient mice develop normally, are fertile, but display partially defective platelet interaction with collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10789-10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue, O., K. Suzuki-Inoue, W. L. Dean, J. Frampton, and S. P. Watson. 2003. Integrin α2β1 mediates outside-in regulation of platelet spreading on collagen through activation of Src kinases and PLCγ2. J. Cell Biol. 160:769-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennings, L. K., S. M. Slack, C. D. Wall, and T. H. Mondoro. 1996. Immunological comparisons of integrin alpha IIb beta 3 (GPIIb-IIIa) expressed on platelets and human erythroleukemia cells: evidence for cell specific differences. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 22:23-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judd, B. A., P. S. Myung, L. Leng, A. Obergfell, W. S. Pear, S. J. Shattil, and G. A. Koretzky. 2000. Hematopoietic reconstitution of SLP-76 corrects hemostasis and platelet signaling through αIIbβ3 and collagen receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12056-12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd, B. A., P. S. Myung, A. Obergfell, E. E. Myers, A. M. Cheng, S. P. Watson, W. S. Pear, D. Allman, S. J. Shattil, and G. A. Koretzky. 2002. Differential requirement for LAT and SLP-76 in GPVI versus T-cell receptor signaling. J. Exp. Med. 195:705-717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung, S. M., and M. Moroi. 1998. Platelets interact with soluble and insoluble collagens through characteristically different reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14827-14837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung, S. M., and M. Moroi. 2000. Signal-transducing mechanisms involved in activation of the platelet collagen receptor integrin α2β1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8016-8026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keely, P. J., and L. V. Parise. 1996. The α2β1 integrin is a necessary co-receptor for collagen-induced activation of Syk and the subsequent phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ2 in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26668-26676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kehrel, B., L. Balleisen, R. Kokott, R. Mesters, W. Stenzinger, K. J. Clemetson, and J. van de Loo. 1988. Deficiency of intact thrombospondin and membrane glycoprotein Ia in platelets with defective collagen-induced aggregation and spontaneous loss of disorder. Blood 71:1074-1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura, T., H. Kihara, S. Bhattacharyya, H. Sakamoto, E. Appella, and R. P. Siraganian. 1996. Downstream signaling molecules bind to different phosphorylated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) peptides of the high-affinity IgE receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271:27962-27968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Locke, D., H. Chen, Y. Liu, C. Liu, and M. L. Kahn. 2002. Lipid rafts orchestrate signaling by the platelet receptor glycoprotein VI. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18801-18809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lusis, A. J. 2000. Atherosclerosis. Nature 407:233-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcinkiewicz, C., R. R. Lobb, M. M. Marcinkiewicz, J. L. Daniel, J. B. Smith, C. Dangelmaier, P. H. Weinreb, D. A. Beacham, and S. Niewiarowski. 2000. Isolation and characterization of EMS16, a C-lectin type protein from Echis multisquamatus venom, a potent and selective inhibitor of the α2β1 integrin. Biochemistry 39:9859-9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenzie, S. E., S. M. Taylor, P. Malladi, H. Yuhan, D. L. Cassel, P. Chien, E. Schwartz, A. D. Schreiber, S. Surrey, and M. P. Reilly. 1999. The role of the human Fc receptor Fc gamma RIIA in the immune clearance of platelets: a transgenic mouse model. J. Immunol. 162:4311-4318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendrick, D. L., D. M. Kelly, S. S. duMont, and D. J. Sandstrom. 1995. Glomerular epithelial and mesangial cells differentially modulate the binding specificities of VLA-1 and VLA-2. Lab. Investig. 72:367-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroi, M., S. M. Jung, M. Okuma, and K. Shinmyozu. 1989. A patient with platelets deficient in glycoprotein VI that lack both collagen-induced aggregation and adhesion. J. Clin. Investig. 84:1440-1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieswandt, B., W. Bergmeier, V. Schulte, K. Rackebrandt, J. E. Gessner, and H. Zirngibl. 2000. Expression and function of the mouse collagen receptor glycoprotein VI is strictly dependent on its association with the FcRγ chain. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23998-24002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nieswandt, B., C. Brakebusch, W. Bergmeier, V. Schulte, D. Bouvard, R. Mokhtari-Nejad, T. Lindhout, J. W. Heemskerk, H. Zirngibl, and R. Fassler. 2001. Glycoprotein VI but not α2β1 integrin is essential for platelet interaction with collagen. EMBO J. 20:2120-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieswandt, B., V. Schulte, W. Bergmeier, R. Mokhtari-Nejad, K. Rackebrandt, J. P. Cazenave, P. Ohlmann, C. Gachet, and H. Zirngibl. 2001. Long-term antithrombotic protection by in vivo depletion of platelet glycoprotein VI in mice. J. Exp. Med. 193:459-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nieuwenhuis, H. K., J. W. Akkerman, W. P. Houdijk, and J. J. Sixma. 1985. Human blood platelets showing no response to collagen fail to express surface glycoprotein Ia. Nature 318:470-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Toole, T. E., D. Mandelman, J. Forsyth, S. J. Shattil, E. F. Plow, and M. H. Ginsberg. 1991. Modulation of the affinity of integrin alpha IIb beta 3 (GPIIb-IIIa) by the cytoplasmic domain of alpha IIb. Science 254:845-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obergfell, A., B. A. Judd, M. A. del Pozo, M. A. Schwartz, G. A. Koretzky, and S. J. Shattil. 2001. The molecular adapter SLP-76 relays signals from platelet integrin αIIbβ3 to the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5916-5923. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Pasquet, J. M., B. Gross, L. Quek, N. Asazuma, W. Zhang, C. L. Sommers, E. Schweighoffer, V. Tybulewicz, B. Judd, J. R. Lee, G. Koretzky, P. E. Love, L. E. Samelson, and S. P. Watson. 1999. LAT is required for tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ2 and platelet activation by the collagen receptor GPVI. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8326-8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santoro, S. A. 1986. Identification of a 160,000 dalton platelet membrane protein that mediates the initial divalent cation-dependent adhesion of platelets to collagen. Cell 46:913-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savage, B., M. H. Ginsberg, and Z. M. Ruggeri. 1999. Influence of fibrillar collagen structure on the mechanisms of platelet thrombus formation under flow. Blood 94:2704-2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulte, V., D. Snell, W. Bergmeier, H. Zirngibl, S. P. Watson, and B. Nieswandt. 2001. Evidence for two distinct epitopes within collagen for activation of murine platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 276:364-368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Snell, D. C., V. Schulte, G. E. Jarvis, K. Arase, D. Sakurai, T. Saito, S. P. Watson, and B. Nieswandt. 2002. Differential effects of reduced glycoprotein VI levels on activation of murine platelets by glycoprotein VI ligands. Biochem. J. 368:293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilner, G. D., H. L. Nossel, and E. C. LeRoy. 1968. Aggregation of platelets by collagen. J. Clin. Investig. 47:2616-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wonerow, P., A. Obergfell, J. I. Wilde, R. Bobe, N. Asazuma, T. Brdicka, A. Leo, B. Schraven, V. Horejsi, S. J. Shattil, and S. P. Watson. 2002. Differential role of glycolipid-enriched membrane domains in glycoprotein VI- and integrin-mediated phospholipase Cγ2 regulation in platelets. Biochem. J. 364:755-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodside, D. G., A. Obergfell, L. Leng, J. L. Wilsbacher, C. K. Miranti, J. S. Brugge, S. J. Shattil, and M. H. Ginsberg. 2001. Activation of Syk protein tyrosine kinase through interaction with integrin β cytoplasmic domains. Curr. Biol. 11:1799-1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang, W., R. P. Trible, and L. E. Samelson. 1998. LAT palmitoylation: its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T-cell activation. Immunity 9:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zutter, M. M., S. A. Santoro, J. E. Wu, T. Wakatsuki, S. K. Dickeson, and E. L. Elson. 1999. Collagen receptor control of epithelial morphogenesis and cell cycle progression. Am. J. Pathol. 155:927-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]