Abstract

Mismatch repair is a highly conserved system that ensures replication fidelity by repairing mispairs after DNA synthesis. In humans, the two protein heterodimers hMutSα (hMSH2-hMSH6) and hMutLα (hMLH1-hPMS2) constitute the centre of the repair reaction. After recognising a DNA replication error, hMutSα recruits hMutLα, which then is thought to transduce the repair signal to the excision machinery. We have expressed an ATPase mutant of hMutLα as well as its individual subunits hMLH1 and hPMS2 and fragments of hMLH1, followed by examination of their interaction properties with hMutSα using a novel interaction assay. We show that, although the interaction requires ATP, hMutLα does not need to hydrolyse this nucleotide to join hMutSα on DNA, suggesting that ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα happens downstream of complex formation. The analysis of the individual subunits of hMutLα demonstrated that the hMutSα–hMutLα interaction is predominantly conferred by hMLH1. Further experiments revealed that only the N-terminus of hMLH1 confers this interaction. In contrast, only the C-terminus stabilised and co-immunoprecipitated hPMS2 when both proteins were co-expressed in 293T cells, indicating that dimerisation and stabilisation are mediated by the C-terminal part of hMLH1. We also examined another human homologue of bacterial MutL, hMutLβ (hMLH1–hPMS1). We show that hMutLβ interacts as efficiently with hMutSα as hMutLα, and that it predominantly binds to hMutSα via hMLH1 as well.

INTRODUCTION

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is a highly conserved system which corrects base–base mismatches and insertion–deletion loops arising during DNA replication (reviewed in 1–3). In bacteria, the two protein dimers MutS and MutL constitute the main components of the repair machinery, exerting mismatch recognition and signalling repair initiation. Several eukary otic heterodimers have developed from these prokaryotic homodimers. In humans, hMutSα (hMSH2-hMSH6), hMutSβ (hMSH2-hMSH3), hMutLα (hMLH1-hPMS2) and hMutLβ (hMLH1-hPMS1) were identified, and mutations in their genes (predominantly hMLH1 and hMSH2) segregate with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), a cancer predisposition syndrome (4–7).

Although the repair reaction can be exerted in vitro with protein extracts (8,9), its exact mechanism is still unknown. While MutS and its eukaryotic counterparts are responsible for mismatch recognition (10–13), the function of MutL proteins is more difficult to characterise. They seem to couple mismatch recognition to incision and removal of the nascent DNA strand, followed by resynthesis, which completes the repair reaction.

A major barrier for understanding the initiation of MMR is the seemingly paradoxical interplay of mismatch binding and ATP processing by MutS proteins. While ATP hydrolysis is enforced in the presence of heteroduplex DNA (14,15), ATP binding induces dissociation of MutS proteins from the mismatch (16–20). This raises the question of how repair can be accomplished when ATP hydrolysis, which is likely to signal repair initiation, occurs after ATP binding has induced MutS to leave the mismatched site. Two repair models resolve this conflict by assuming that MutS proteins need to leave the mismatched site in order to search for a strand discrimination signal and to alert the excision machinery. Of these two models, the translocation model assumes that the movement is driven by ATP hydrolysis and serves to loop the faulty DNA duplex prior to strand incision at the base of the arising loop (17). In contrast, the molecular switch model proposes that MutS forms a hydrolysis-independent sliding clamp on DNA after ATP uptake, signalling the finding of a mismatch to repair enzymes located elsewhere on the DNA duplex in a manner similar to G-protein signalling (21,22). Another model suggests that MutS proteins do not lose, but only reduce affinity to DNA after ATP binding, thereby verifying the actual presence of the mismatch. This implies that binding to the mismatch is maintained during repair initiation. Since this model requires a bent DNA to enable MutS to contact the mismatch as well as other proteins bound elsewhere on the DNA duplex, it was referred to as the DNA bending model (23,24).

MutL and its homologues can also hydrolyse ATP (25,26) and bind DNA. Single-stranded DNA is preferred in short substrates (27,28), while yeast MutLα has been found to bind double-stranded DNA efficiently in a cooperative manner when longer substrates are used (28,29). We and others have shown that hMutLα and hMutLβ interact with hMutSα in an ATP-dependent manner, and that this interaction is DNA dependent (27,30,31). While ATP hydrolysis by MutL proteins is essential for MMR (26,32–34), its role within the repair reaction is still unclear. MutL and its eukaryotic counterparts seem to signal mismatch recognition from MutS to downstream proteins [e.g. MutH and UvrD in bacterial MMR (35–37)]. Therefore, MutL proteins have been suggested to be molecular matchmakers, coupling mismatch recognition by MutS to repair (38). The interaction of hMutS and hMutL proteins therefore plays a key role in the initiation of the human repair reaction. However, little is known about the precise contribution of the different ATPases or the protein domains involved in this interaction.

We have previously established an assay using DNA-coupled magnetic beads suitable to produce a specific, ATP- and DNA-length-dependent complex between hMutSα and hMutL heterodimers in protein extracts (27). It was the aim of this study to extend this assay to allow investigation of the protein properties contributing to this interaction. More specifically, we assessed the role of ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα in complex formation and evaluated the contribution of the hMutL subunits hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2 to the interaction. For this aim, we over-expressed hMutLα, hMutLβ, the hMutL subunits hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2, as well as mutants of hMutLα and fragments of hMLH1 in 293T cells. We demonstrate that ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα is not necessary for complex formation, and that the interaction is conferred by the N-terminus of hMLH1, while the C-terminus is responsible for hMutL heterodimerisation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies, reagents and cell lines

Poly(dI·dC) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany), and ATP from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). BamHI and EcoRI were from NEB (Beverly, MA). Alkaline phosphatase was from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). Anti-hMLH1 (G168-728) and anti-hPMS2 (A16-4) were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Anti-hMSH2 (M34520) and anti-hMSH6 (G70220) were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) and anti-hMLH1 (Ab-1) from Oncogene (San Diego, CA). A polyclonal hPMS1 antiserum (39) was kindly provided by Dr Josef Jiricny (University of Zürich, Switzerland). HeLa cells were purchased from DMSZ (Braunschweig, Germany) and grown in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FCS. 293 and 293T cells were grown in DMEM nut mix F-12 (HAM) with 10% FCS. HCT-116 cells were kindly provided by Dr C. Richard Boland (University of California, CA) and grown in DMEM with 10% FCS. All oligonucleotides were purchased from BioSpring (Frankfurt, Germany).

Expression vectors for hMLH1, hPMS2 and hPMS1

The pcDNA3.1 expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing the entire open reading frame of hMLH1 was a gift of Dr Hong Zhang (Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). The pSG5 expression vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) containing full-length hPMS2 cDNA was provided by Dr Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD). Nucleotide and amino acid positions refer to the 2484 bp hMLH1 mRNA (GenBank accession no. U07343.1) and the 756 amino acid hMLH1 sequence (GenBank accession no. AAC50285), respectively (40). The expression vector for hPMS1 was generated by cloning the full-length hPMS1 cDNA into pSG5. In short, total RNA was extracted from human lymphocytes using the TriStar reagent (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany). hPMS1 cDNA was produced by reverse transcription with Superscript II (Invitrogen) using the hPMS1-specific primer 5′-gaacacactctcatgtagtttc-3′ and amplified using the same primer together with 5′-gcaagctgctctgttaaaagcg-3′. The PCR product was gel-purified and cloned into the pCR2.1 cloning vector (Invitrogen). Escherichia coli K12 were transformed and insert-carrying clones were analysed by sequencing. A clone carrying the full-length human PMS1 cDNA corresponding to the published sequence (GenBank accession no. NM_000534) was digested with EcoRI. The insert was gel-purified and cloned into EcoRI-digested, dephosphorylated pSG5. A clone carrying the correctly inserted cDNA was verified by sequencing.

Generation of vectors for expression of hMutLα ATPase mutants and hMLH1 fragments

The hMutLα ATPase double mutant hMutLα-mpEA was created by site-directed mutagenesis of the hMLH1 and hPMS2 cDNAs (in pcDNA3.1 and pSG5, respectively). The QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following primer sets: 5′-ccagctaatgctatcaaagcgatgattgagaac-3′ (sense) and 5′-gttctcaatcatcgctttgatagcattagctgg-3′ (antisense) for hMLH1, and 5′-gcactgcggtaaaggcgttagtagaaaacagtc-3′ (sense) and 5′-gactgttttctactaacgcctttaccgcagtgc-3′ (antisense) for hPMS2. hMLH1 fragments were generated by PCR amplification of the desired regions of the hMLH1 cDNA. Special primers were constructed to include BamHI restriction sites on both ends of the PCR product as well as start and stop codons in-frame with the new cDNAs. The primers were as follows: 5′-gtggatccatgtcgttcgtggcaggggttat-3′ and 5′-gtggatcctcaactagtgaggttaatgatcc-3′ for LN56, 5′-gtggatccatgagcatcctggagcgggtgcag-3′ and 5′-gtggatcctcaacacctctcaaagactttgt-3′ for LM42, and 5′-gtggatccatggtagctgatgttaggacact-3′ and 5′-gtggatcctcaaaaattggcaaaatcataaa-3′ for LC49. After amplification, the PCR products were purified and ligated into BamHI-digested, dephosphorylated pSG5. Finally, all constructs were sequenced for verification.

Transfection, extract preparation and immunoprecipitation

293T cells were transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation according to standard procedures (41). Briefly, 293T cells were spread in 75 cm2 flasks to 70% confluency in 10 ml of medium 24 h prior to transfection. The medium was replaced 1 h before transfection. The suspension containing the calcium phosphate–DNA precipitate (1 ml) was added to the cell medium. After 5 h, the transfection medium was replaced by fresh medium. Cells were harvested after 24 h and whole cell extracts were prepared.

Similar to nuclear extraction, cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in four times the packed cell volume of hypotonic buffer [10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM DTT]. The suspension was frozen at –80°C and thawed on ice for lysis. This suspension containing both nuclei and cytoplasmatic extract was supplemented with an identical volume of hypertonic buffer [10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 830 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM PMSF, 5 mM DTT, 34% glycerol]. The suspension was rocked on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged (4°C, 23 000 g). The supernatant (whole cell extract) was aliquoted and stored at –80°C. Expression of the desired protein was verified by western blotting in comparison to extracts of untransfected 293T cells (negative control) and extracts of 293 or TK6 cells (expressing wild-type levels of MMR proteins) as a positive control. Nuclear extracts were prepared from untransfected 293, HeLa, TK6 and HCT-116 cells as described previously (27).

Immunoprecipitations were carried out in a total volume of 500 µl containing protein extract, 50 mM TE pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X, 5 mM PMSF, 5 mM DTT and 1 µg of anti-hMLH1 G168-728 (Pharmingen). The incubation was kept at 4°C for 1 h under agitation. Protein G agarose was added and the suspension kept at 4°C for 3 h under agitation. Supernatant was taken off and the agarose was washed three times with 500 µl of washing buffer (50 mM TE pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X, 5 mM PMSF, 5 mM DTT). Precipitated proteins were detached by boiling in sample buffer for 5 min and analysed by western blotting.

DNA substrates and preparation of DNA-coupled magnetic beads

The 81mer DNA substrates were produced as described previously (27). Furthermore, a 200 bp homoduplex substrate was used for this work. This substrate was generated by amplification of a 200 bp fragment of the human hPMS2 cDNA. One of the primers was 5′-labelled with biotin to allow binding to streptavidin-coupled beads. The following primers were used: biotin-5′-gcgagctgagagctcgagtac-3′ (sense) and 5′-gaaacttcaataagatccactccatagtcc-3′ (antisense). The amplificate was purified and coupled to Dynabeads streptavidin as described (27). For every experiment, DNA-coupled beads were produced in excess and aliquoted to ensure homogeneity of all samples.

hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay

The hMutSα–hMutL interaction was assessed essentially as described previously in the DNA binding assay (27). Briefly, cell extract (150 µg protein) was incubated in 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 50 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM DTT and 1 µg of poly(dI·dC) in a total volume of 300 µl for 5 min at room temperature. For investigation of hMutL constructs expressed in 293T cells, 5 µg of this extract was diluted with 145 µg of HCT-116 nuclear extract. For each experiment, two identical samples from one master mix were prepared. Both samples were added to an aliquot of DNA-coupled beads and placed on ice. All subsequent steps were performed on ice. After 20 min incubation, ATP was added to one sample to produce a final concentration of 250 µM. After a further 5 min, the beads were collected with a magnet and the supernatant was taken off. To ensure complete removal of the supernatant, the cup was briefly centrifuged, the beads were again collected and residual buffer was taken off. The beads were then resuspended in 20 µl of elution buffer (700 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF and 0.5 mM DTT) and incubated for 5 min. The beads were collected and the supernatant stored for analysis. A second elution step was performed with 20 µl of elution buffer as above, only with 1000 mM NaCl. This elution was also analysed by western blotting and verified that ATP had taken effect, since it abolished hMutSα signals in this elution fraction (27). Although this elution was always performed as a control, these data have been omitted in most figures. This assay produced a 2–3-fold increase in binding of hMutL heterodimers after ATP addition as evaluated by densitometric analysis.

Western blotting

The proteins were separated on 10 or 12.5% polyacrylamide gels, followed by western blotting on nitrocellulose membranes and antibody detection using standard procedures. hMLH1 was detected with Pharmingen G168-728 except for the blot shown in Figure 8 (top), which was detected with Oncogene Ab-1. Densitometric evaluation of the western blots was performed with GelScan 5.0 Software (BioSciTec, Frankfurt, Germany).

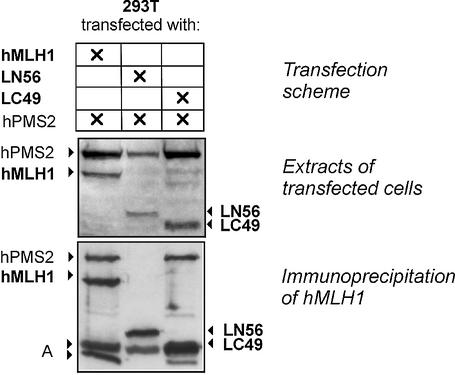

Figure 8.

Expression and co-immunoprecipitation of hPMS2 with hMLH1 fragments. Top: Transfection scheme for cotransfection of 293T cells with hMLH1-hPMS2 (hMutLα), LN56-hPMS2 or LC49-hPMS2. Middle: protein extracts of these transfections were prepared and 50 µg were separated on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel, followed by western blotting and detection of hMLH1 and hPMS2. Bottom: an immunoprecipitation was performed according to the protocol described in Materials and Methods with an antibody against hMLH1 (G168-728; Pharmingen) using 100 µg of the hMLH1-hPMS2 and LC49-hPMS2 extracts, respectively, and 200 µg of the LN56-hPMS2 extract to adjust the experiment to the different expression levels of the proteins. For one experiment, the extract containing hMutLα was used, while the antibody was omitted as a control for successful washing (data not shown). The western blot of the precipitates is shown (hMLH1 and hPMS2 were detected). A, non-specific signals from degradation products and the immunoprecipitating antibody.

RESULTS

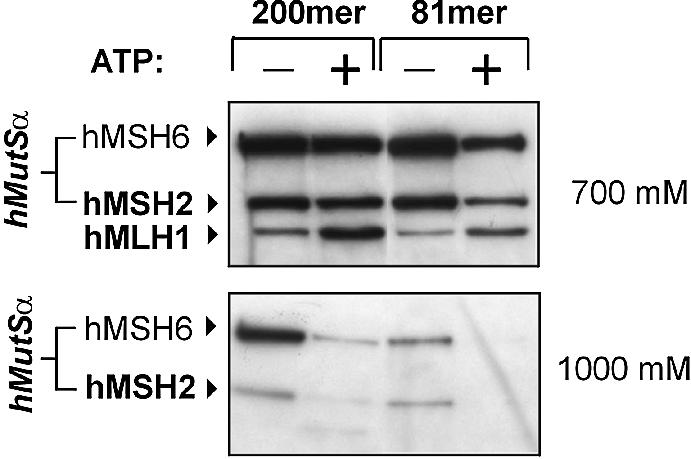

200mer homoduplex DNA improves detection of the specific complex of hMutLα with hMutSα

We have previously demonstrated that hMutLα and hMutLβ bind to DNA substrates coupled to magnetic beads in an ATP-dependent manner only when hMutSα is present (27). This binding therefore represents a specific complex of hMutLα and hMutLβ with hMutSα on DNA. This interaction is improved when substrate length is increased from the previously used 81mer DNA substrate to 200mer DNA. The longer DNA substrate is more efficient in retaining hMutSα in the presence of ATP and also recruits hMLH1 more efficiently (Fig. 1). The 200mer homoduplex therefore supports complex formation of hMutSα and hMutL proteins better than the 81mer homoduplex, which is in agreement with previous findings showing that the interaction depends on DNA length and improves on longer substrates (27,30).

Figure 1.

Complex formation of hMutLα with hMutSα on 200mer and 81mer DNA substrates. HeLa nuclear extract (150 µg) was incubated with 200mer or 81mer homoduplex DNA coupled to magnetic beads according to the hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay described in Materials and Methods. For each DNA substrate, two identical incubations were performed for 20 min. Then, ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of the two mixtures (signified by ‘+’), and incubations were continued for 5 min. The supernatant of the DNA beads was removed and proteins bound to the substrates were eluted in two fractions, first with 700 mM NaCl (top), then with 1000 mM NaCl (bottom). Both elutions were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and blotted. hMSH2, hMSH6 and hMLH1 were detected using specific antibodies. The 700 mM NaCl fraction quantitatively elutes hMLH1 and its partner proteins hPMS1 and hPMS2 (hMutLα and hMutLβ) (27), while both fractions together elute hMutSα quantitatively. The ATP-dependent recruitment of hMLH1 to the DNA substrate becomes visible in the 700 mM fraction. The 1000 mM NaCl fraction serves as control that ATP has taken effect, since this nucleotide abolishes the hMutSα signal in this elution fraction (27).

The hMutSα–hMutL interaction does not depend on mismatched base pairs in this assay (27). Therefore, homoduplex DNA is suitable for the measurement of this interaction, though it is not the substrate of the repair reaction (see Discussion). Since homoduplexes are more easily generated and produced identical results as heteroduplexes in this assay whenever tested, we used the 200mer homoduplex in most of the following experiments. In cases when a contribution of mismatched base pairs to complex formation was possible, we performed additional experiments with heteroduplex substrates in parallel (see below).

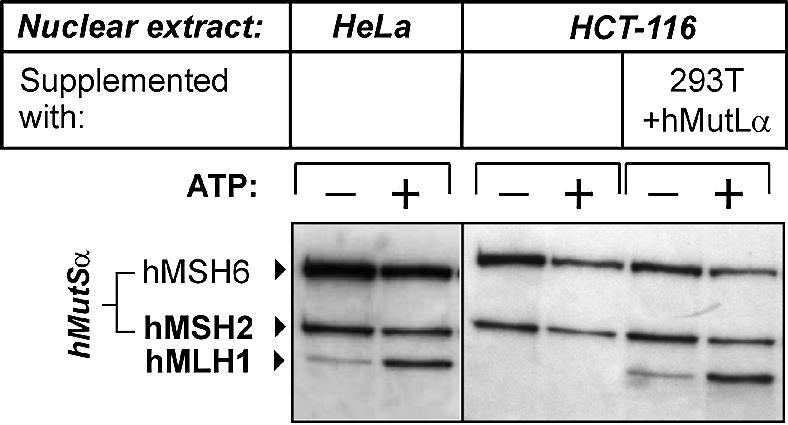

Interaction of hMutLα expressed in 293T cells with hMutSα can be assessed with HCT-116 nuclear extract

293T cells are deficient in heteroduplex repair because of the lack of hMutLα, which is not expressed due to hMLH1 promoter methylation (42). Transfection of hMutLα restores MMR activity of 293T extracts, which has been utilised to study the effect of HNPCC-associated genetic changes of hMLH1 on the MMR status in vitro (42). Since the concentration of hMutLα in extracts of transfected 293T cells drastically exceeds the biological concentration of this heterodimer observable in HeLa or TK6 extracts (Fig. 2), we diluted them with HCT-116 nuclear extract to reduce the hMutLα concentration to biological levels. HCT-116 cells are also deficient in hMutL proteins, and the interaction assay works well with this extract when hMutLα is supplemented (27). This procedure produced a 2–3-fold increase in binding of recominant hMutLα, which is comparable to the recruitment of endogenous hMutLα in HeLa extracts (Fig. 3). This approach therefore allows expression of any desired hMutL construct in 293T cells with subsequent examination of its interaction properties with hMutSα.

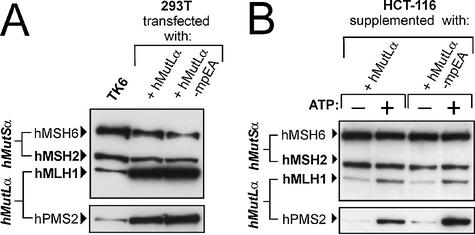

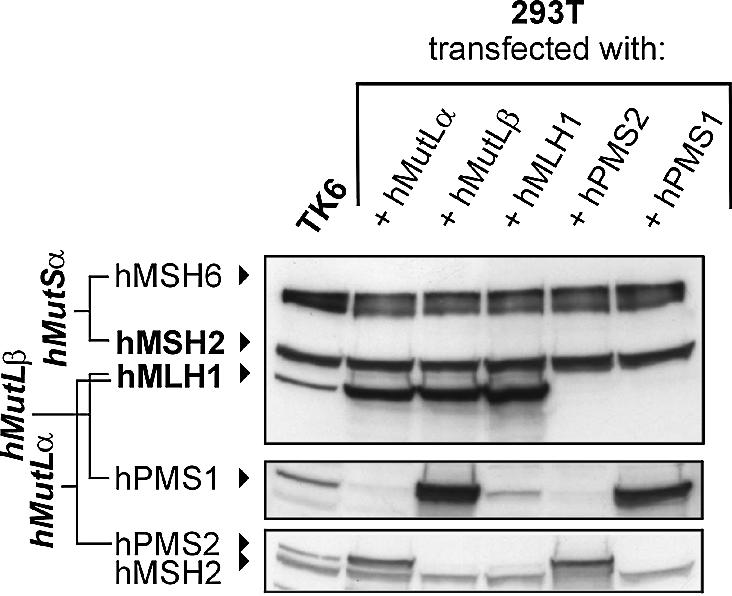

Figure 2.

Expression of hMutLα, hMutLβ, hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2 in 293T cells. 293T cells were either cotransfected with hMLH1-hPMS2 (hMutLα) or hMLH1-hPMS1 (hMutLβ) or transfected with hMLH1, hPMS2 or hPMS1 as described in Materials and Methods. Extracts were prepared according to the protocol in Materials and Methods and 50 µg of total protein were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. For comparison, a 50 µg extract of the MMR proficient cell line TK6 was analysed in parallel. hMLH1, hMSH2, hMSH6 (top), hPMS1 (middle) and hPMS2 (bottom, upper signal; the lower signal is hMSH2) were detected using specific antibodies. The signals of hMutSα (hMSH2 and hMSH6) serve as a loading control.

Figure 3.

Interaction of hMutLα expressed in 293T cells with hMutSα can be assessed with HCT-116 nuclear extract. The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and Materials and Methods. Left: the beads were incubated with nuclear extracts of HeLa cells (150 µg). Right: the DNA beads were incubated with a nuclear extract of the hMutL-deficient cell line HCT-116 (150 µg), or with a combination of HCT-116 extract (145 µg) with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells transfected with hMutLα. In all cases, ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’). Bound proteins were eluted from the DNA beads with 700 and 1000 mM NaCl. The western blot of hMutSα and hMLH1 of the 700 mM elution fraction is shown.

ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα is not necessary for interaction

The presence of ATP is necessary for recruitment of hMutLα by hMutSα (27,31–34,43). Both hMutLα and hMutSα are ATPases. This raises the question of which protein needs to bind or process ATP to start the interaction. The ATP concentration effecting hMutSα–hMutL complex formation is identical to the ATP concentration altering DNA binding of hMutSα [1–10 µM (27)], suggesting a concerted process. It cannot be excluded, however, that the hMutL ATPase may also contribute to complex formation. To investigate whether hMutLα needs to hydrolyse ATP to join hMutSα, we generated a hMutLα mutant (designated hMutLα-mpEA) with one amino acid exchange in the ATPase domains of each of its subunits hMLH1 and hPMS2. Both exchanges (hMLH1 E34A and hPMS2 E41A) alter a conserved glutamate, which is homologous to E.coli MutL E29, to alanine. This glutamate positions a water molecule for a nucleophile attack on the γ-phosphate of ATP, thus catalysing ATP hydrolysis (44). The mutation to alanine abolishes ATP hydrolysis of MutL proteins and MMR in bacteria, yeast and humans (26,31,33). Nevertheless, hMutLα-mpEA and its yeast homologue showed the same ATP-induced conformational changes as the wild-type protein in proteolysis experiments (26,31), demonstrating that the mutations do not attenuate ATP binding and its conformational effects. Furthermore, no reduction of expression and dimerisation was observed in these studies.

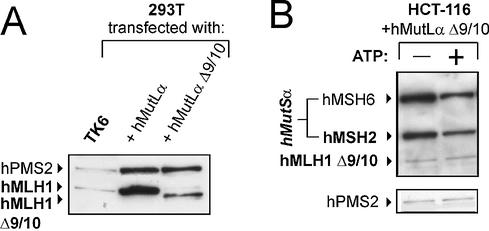

hMutLα-mpEA was over-expressed in 293T cells, and expression levels were similar to those of wild-type hMutLα (Fig. 4A). The ATPase mutant interacted as efficiently with hMutSα as wild-type hMutLα (Fig. 4B), confirming that ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα is not necessary for ternary complex formation.

Figure 4.

Expression of hMutLα-mpEA and interaction with hMutSα. (A) hMLH1-hPMS2 (hMutLα) or hMLH1 E34A-hPMS2 E41A (hMutLα-mpEA) were cotransfected into 293T cells. Protein extracts of the transfected cells and, for comparison, extract of the MMR proficient cell line TK6 (50 µg each) were separated in a 10% polyacrylamide gel and blotted. hMSH6, hMSH2, hMLH1 and hPMS2 were detected using specific antibodies. The signals of hMutSα (hMSH2 and hMSH6) serve as a loading control. (B) The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and Materials and Methods. The beads were incubated with 145 µg of nuclear extract of HCT-116 cells supplemented with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells expressing either wild-type hMutLα or hMutLα-mpEA from the transfection displayed in (A). ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’). The western blots of hMSH6, hMSH2, hMLH1 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM NaCl elution fraction are shown.

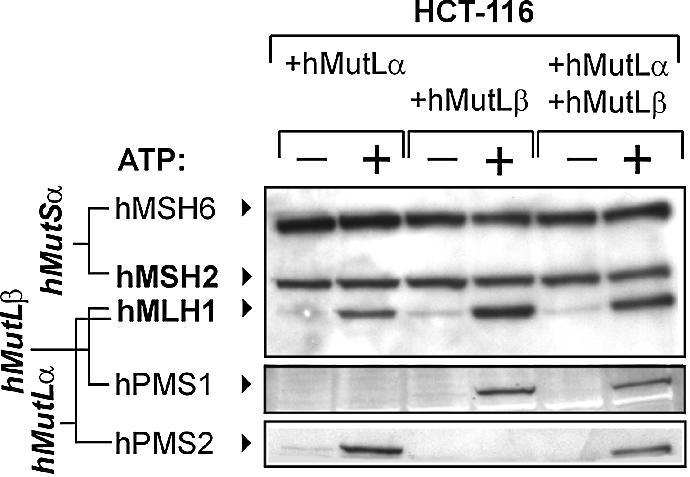

hMutSα can recruit both hMutLα and hMutLβ independently

Both hMutLα and hMutLβ are recruited to the DNA by hMutSα after addition of ATP (27). To assess whether both heterodimers can be recruited only together or also bind individually, we transfected them separately into 293T cells. Both were strongly expressed (Fig. 2, lanes 2 and 3). No hPMS2 was detectable in hMutLβ-transfected cells, while no hPMS1 was detectable in hMutLα-transfected cells, excluding contaminations with the respective hPMS partners. Both hMutL heterodimers interacted efficiently with hMutSα in the assay even when used individually (Fig. 5, lanes 1–4). Furthermore, a mixture of both hMutLα and hMutLβ did not further improve complex formation either (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6), suggesting that binding does not show cooperative effects.

Figure 5.

Interaction of hMutLα and hMutLβ with hMutSα. The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed according to Figure 1 and the protocol described in Materials and Methods with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA. Incubations were performed with a nuclear extract of HCT-116 cells (145 µg) supplemented with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells transfected with hMutLα (lanes 1 and 2), hMutLβ (lanes 3 and 4) or with 2.5 µg of each extract (lanes 5 and 6) from the transfection displayed in Figure 2. ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’). The western blots of hMSH6, hMSH2, hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM NaCl elution fraction are shown.

hMLH1 is predominantly responsible for hMutL-hMutSα interaction

The binding of hMutLα and hMutLβ to hMutSα may be conferred either by one of the hMutL-heterodimer subunits alone or by concerted binding of both subunits simultaneously. To assess which hMutL subunits establish the interaction, we expressed and examined hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2 individually. hMLH1 was as strongly expressed as when transfected with its heterodimeric partners (hMutLα or hMutLβ, Fig. 2). While no hPMS2 was detectable in the extract of hMLH1-transfected cells, a weak co-expression of hPMS1 was observed (Fig. 2, lane 4, middle). Since hMLH1 has been shown to stabilise its heterodimeric partner proteins (39,45–47), this co-expression likely results from stabilisation of endogenous hPMS1.

Although unquestionable evidence exists that neither hPMS1 nor hPMS2 are stable in the absence of their heterodimeric counterpart hMLH1 (see Discussion), we successfully expressed both subunits to high concentrations in 293T cells (Fig. 2, lanes 5 and 6). Neither extract contained hMLH1.

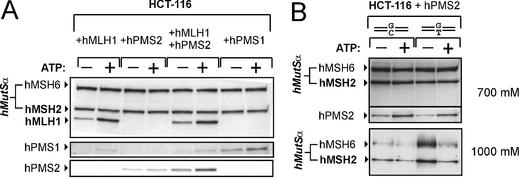

Performance of the interaction assay with these three individual hMutL subunits revealed that hMLH1 interacted efficiently with hMutSα (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, hPMS1 and hPMS2 showed much weaker basic binding and a significantly attenuated ATP-promoted complex formation with hMutSα (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4, 7 and 8). Furthermore, supplementation of hMLH1 restored hPMS2 binding activity as well as its full ATP reactivity (Fig. 6A, bottom, lanes 5 and 6 versus 3 and 4). To exclude that the use of homoduplex DNA instead of a mismatched substrate caused the weak reaction of hPMS2, we compared its interaction with hMutSα on 81mer homoduplex versus heteroduplex DNA. hMutSα showed improved binding to the heteroduplex in the absence of ATP in the 1000 mM elution fraction (Fig. 6B, bottom) as reported previously (27). Although hMutSα therefore clearly reacted to the presence of the mismatch, no difference in hPMS2 recruitment between homo- and heteroduplex substrates was detectable (Fig. 6B, middle).

Figure 6.

Interaction of hMutL subunits with hMutSα. (A) The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and Materials and Methods. The beads were incubated with 145 µg of nuclear extract of HCT-116 cells supplemented with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells expressing either hMLH1, hPMS2 or hPMS1 from the transfection displayed in Figure 2. In one case, the HCT-116 extract was supplemented with two extracts of 293T cells, one prepared from cells transfected with hMLH1, the other from cells transfected with hPMS2 (2.5 µg each). ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’). The western blots of hMSH6, hMSH2, hMLH1, hPMS1 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM NaCl elution fraction are shown. (B) The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with a nuclear extract of HCT-116 (145 µg) supplemented with an extract of 293T cells transfected with hPMS2 (5 µg) according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and the protocol in Materials and Methods. DNA beads coupled with 81mer duplexes were used that were either correctly paired (GC) or contained a mismatch (GT). ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples (signified by ‘+’) prior to elution. The western blots of hMSH6, hMSH2 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM NaCl elution fraction are shown. Furthermore, the western blot of hMSH6 and hMSH2 of the 1000 mM NaCl elution fraction is shown to demonstrate that the presence of a mismatch actually affected hMutSα binding: the mismatch confers a greater elution resistance to hMutSα in the absence of ATP, resulting in increased signals of hMSH2 and hMSH6 on heteroduplex compared to homoduplex (third lane versus first lane). For detailed characterisation of this effect, see Plotz et al. (27).

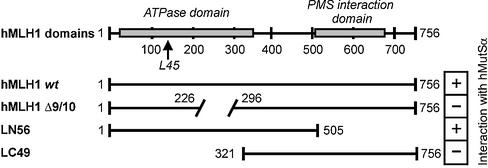

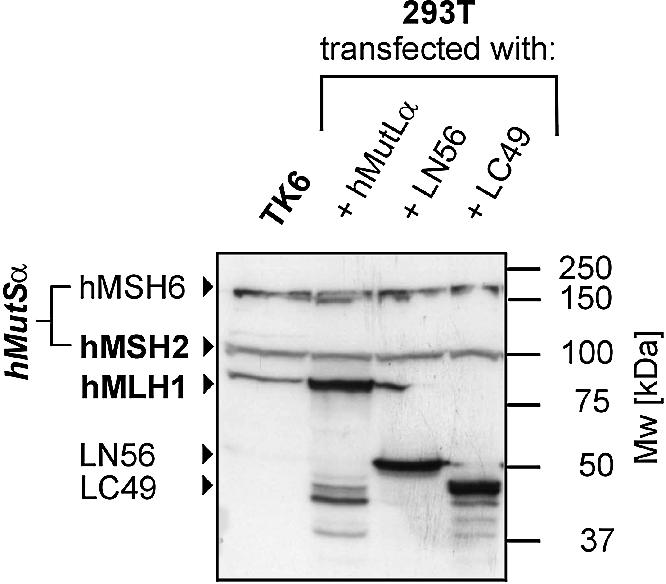

Only the N-terminus of hMLH1 confers interaction with hMutSα

Based on the finding that the interaction of hMutL proteins with hMutSα is predominantly conferred by hMLH1, we generated three fragments of hMLH1 to broadly determine which protein domains are essential for interaction. Three fragments of the hMLH1 cDNA, each containing start and stop codons, were produced and cloned into the pSG5 expression vector. The N-terminal cDNA fragment (LN56) covers amino acids 1–505, the centrally located fragment (LM42) covers amino acids 201–571, while the C-terminal fragment (LC49) included amino acids 321–756. They correspond to proteins of calculated molecular weights of 56, 42 and 49 kDa, respectively.

All three constructs were transfected into 293T cells, but only LN56 and LC49 were strongly expressed (Fig. 7). LM42 could not be detected by western blotting with two different monoclonal antibodies (data not shown). Since both antibodies readily detected LN56 as well as LC49, both must recognise epitopes located in the centre of hMLH1, excluding a pure detection failure. In contrast to extracts of cells transfected with hMLH1, those with LN56 or LC49 did not contain detectable amounts of hPMS1 or hPMS2 (data not shown).

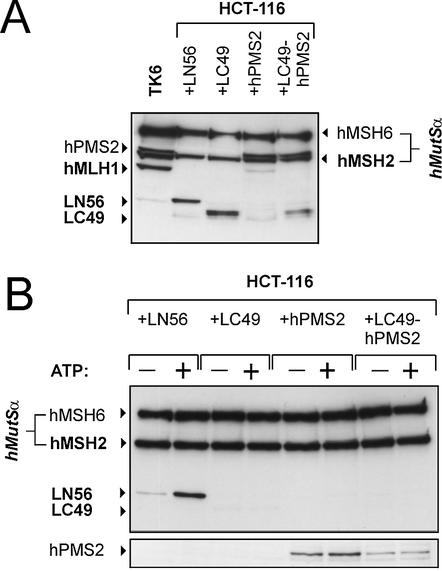

Figure 7.

Expression of hMLH1 fragments in 293T cells. 293T cells were transfected or cotransfected with either hMLH1-hPMS2 (hMutLα), LN56 or LC49. Extracts were prepared according to the protocol in Materials and Methods. Fifty micrograms of total protein were separated on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel. For comparison, a 50 µg extract of the MMR proficient cell line TK6 was analysed in parallel. hMLH1, hMSH2 and hMSH6 were detected using specific antibodies. The hMLH1 antibody also recognised the hMLH1 fragments LN56 (56 kDa) and LC49 (49 kDa). The signals of hMutSα (hMSH2 and hMSH6) serve as a loading control. The non-specific bands visible between 37 and 50 kDa in the extracts of cells transfected with hMutLα (and also, to some degree, in the transfections with LC49) most likely represent degradation products of these proteins.

Co-expression of LN56 or LC49 with hPMS2 showed that LC49 supported expression of hPMS2 more than LN56 (Fig. 8, middle). Furthermore, only hMLH1 and LC49, but not LN56, were able to co-immunoprecipitate hPMS2 (Fig. 8, bottom), proving that the domain for heterodimerisation with hPMS2 is lost in LN56.

While hMutSα recruited LN56 very efficiently to the DNA substrate, neither basic binding nor ATP-dependent recruitment were detectable with LC49 (Fig. 9B, lanes 1–4). Testing the interaction of the LC49-hPMS2 heterodimer showed that LC49 did not support hPMS2 recruitment (or vice versa), underlining that neither hPMS2 nor the C-terminal part of hMLH1 contain domains efficiently supporting interaction with hMutSα (Fig. 9B, lanes 3–8). Since LN56 did not heterodimerise with hPMS2, we did not test the interaction properties of this cotransfection.

Figure 9.

Interaction of hMLH1 fragments with hMutSα. The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and Materials and Methods. The beads were incubated with 145 µg of nuclear extract of HCT-116 cells supplemented with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells transfected with LN56, LC49, hPMS2 or LC49-hPMS2 from the transfection displayed in Figures 7 and 8. ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’). (A) Western blot of the original incubation mixtures of this experiment showing the presence and adequate concentration of the hMutL constructs in the samples. (B) Western blots of hMSH6, hMSH2, hMLH1 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM NaCl elution fraction are shown.

A hMLH1 deletion mutant does not interact with hMutSα

hMLH1Δ9/10 is a hMLH1 mutant which has lost exons 9 and 10, leading to an in-frame deletion of 210 bp (70 amino acids) in the ATPase domain (amino acids 227–296). This mutant has been described to be associated with HNPCC (48–50), but has also been found as a common splicing variant in healthy volunteers (51,52), which raised the question of its pathogenicity. We have recently shown that this mutant is deficient in strand-specific MMR (42). Expression resulted in an hMLH1 protein of the expected lower molecular mass (Fig. 10A). This deletion mutant showed only very weak basic binding in the hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay, and did not react to ATP addition (Fig. 10B). Analogous to the experiment shown in Figure 6B, we verified that interaction of hMutLα Δ9/10 indeed failed on heteroduplex substrates as well as homoduplex substrates (data not shown). This finding demonstrates that MMR fails at the early step of complex formation with hMutLα Δ9/10.

Figure 10.

Expression of hMutLα Δ9/10 and interaction with hMutSα. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected either with hMLH1-hPMS2 (hMutLα) or hMLH1Δ9/10-hPMS1 (hMutLα Δ9/10) as described in Materials and Methods. Extracts prepared according to the protocol in Materials and Methods were separated on a 10% polyacrylamide gel (50 µg of total protein in each lane) and blotted. For comparison, a 50 µg extract of the MMR proficient cell line TK6 was analysed in parallel. hMLH1 and hPMS2 were detected using specific antibodies. (B) The hMutSα–hMutL interaction assay was performed with magnetic beads coupled with 200 bp homoduplex DNA according to the procedure described in Figure 1 and Materials and Methods. The beads were incubated with nuclear extracts of HCT-116 cells (145 µg) supplemented with a 5 µg extract of 293T cells transfected either with wild-type hMutLα or with hMutLαΔ9/10 from the transfection displayed in (A). ATP (250 µM final concentration) was added to one of two identical samples prior to elution (signified by ‘+’), and bound proteins were eluted from the DNA beads. The western blots of hMSH2, hMSH6, hMLH1 and hPMS2 of the 700 mM elution fraction are shown.

DISCUSSION

The experimental investigation of the hMutSα–hMutL interaction is challenging since it only occurs under certain conditions (in the presence of ATP and a DNA duplex substrate of sufficient length). This restricts the use of classical approaches for protein interaction measurement like co-immunoprecipitation or GST fusion protein pulldown assays. For detailed characterisation of the interaction, it is most promising to capture hMutSα–hMutL complexes on the matrix on which they form, the DNA. This has been attempted in several systems with bacterial, yeast and human proteins using either gel retardation assays or surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy (24,27,30,31,53–55). In the present work, we show that a novel DNA binding assay we recently used for proving that hMutSα interacts with hMutLα and hMutLβ (27) can be extended to investigate the interaction properties of diverse hMutL constructs expressed in 293T cells, providing a flexible tool for detailed characterisation of this interaction.

Both homoduplex and heteroduplex substrates efficiently support interaction in this assay, therefore binding to a mismatch was not a precondition for complex formation under the applied experimental conditions. The complexes arising on homoduplex DNA should not be competent to initiate repair since they have not detected a mismatched site. However, since no difference could be detected between complex formation on faulty and correct DNA substrates, interaction between hMutSα and hMutL proteins may either be possible independently of the type of DNA substrate or hMutSα is (under the experimental conditions used) transferred artificially into a mode it can biologically only assume after encountering a mismatch. Either way, the use of homoduplex substrates does not flaw the general applicability of the assay for the examination of complex formation.

ATP hydrolysis is necessary for the processing of faulty DNA by MMR proteins, and MutL ATPase mutants deficient in ATP hydrolysis are defective in strand-specific MMR of bacteria, yeast and humans (26,31–34). However, the hMutSα–hMutLα interaction occurred under conditions which do not favour ATP hydrolysis (incubations on ice and at relatively low concentration of Mg2+). Furthermore, the interaction is not attenuated by the well characterised point mutation of hMutLα-mpEA, which blocks ATP hydrolysis of hMutLα. This suggests that ATP hydrolysis by hMutLα occurs downstream of the assembly of hMutSα and hMutLα on DNA. This finding supports previous experiments performed with purified proteins and gel-shift assays (31). The possibility that binding of ATP by hMutLα (without hydrolysis) is a precondition of complex formation, however, cannot be excluded by these experiments.

Extensive evidence proves that neither hMSH6/hMSH3 nor hPMS1/hPMS2 are stable in the absence of their respective smaller heterodimeric partners hMSH2 and hMLH1 (39,45–47). This is also illustrated by the observation that cell lines lacking hMSH2 or hMLH1 do not show significant protein levels of hMSH6/hMSH3 or hPMS1/hPMS2 either, even if their genes do not carry mutations. Consequently, we did not expect that transfection of hPMS1 or hPMS2 would yield sufficient protein for further investigations. To our surprise, a high expression of both subunits was achieved in our experiments. This was not attributable to a general stability of hPMS1 and hPMS2 in 293T cells, since this cell line also lacks endogenous hPMS proteins due to the absence of hMLH1. Rather, we assume that the degradation of hPMS proteins was not efficient enough to compete with the strong expression of the subunits in 293T cells after transfection. Nevertheless, hMLH1 exerted a stabilising effect, which became obvious when hPMS2 protein levels were compared in extracts of cells cotransfected either with the N-terminal or the C-terminal part of hMLH1. LC49 exhibited a stabilising effect and could co-precipitate hPMS2, which was not possible with LN56. The results demonstrate that the dimerisation domain of hMLH1 is located within its C-terminus, and that dimerisation with hMLH1 confers stability to hPMS2, confirming previous studies (56,57).

The individual expression of all hMutL subunits further enabled the investigation of their contributions to interaction with hMutSα. Since hMutSα and hMutLα interact not only in cell extracts, but also when used purified (27,30,31), it can be concluded that the interaction is accomplished through a direct contact between both heterodimers. Only hMLH1 efficiently joined hMutSα on DNA in an ATP-dependent manner, demonstrating that hMLH1 predominantly confers this interaction. Although our hMLH1 preparation contained a small amount of hPMS1, it was not hMutLβ that produced this result, since hPMS1-free preparations of the N-terminal hMLH1-fragment LN56 also interacted (see below).

One caveat must be considered in the interpretation of these results: since both hPMS proteins were expressed in the absence of their stabilising partner hMLH1, misfolding may underlie the failure to accomplish interaction with hMutSα. Two important observations, however, disfavour this possibility. First, we expressed hPMS2 in the presence LC49, which conferred stabilisation of hPMS2. Although hPMS2 should therefore be correctly folded in LC49-hPMS2, this heterodimer was unable to interact efficiently with hMutSα either. Secondly, when hPMS2 was complemented with hMLH1, the reactivity of hPMS2 was fully restored: hPMS2 was folded correctly enough to re-establish an interacting hMutLα heterodimer with hMLH1. One can therefore state that the interaction of hMutSα with hMutL heterodimers is predominantly conferred by hMLH1. Nevertheless, the finding that the hPMS subunits have a very weak interacting ability suggests that PMS1 and PMS2 contact hMutSα once the complex has been established by hMLH1.

The examination of hMLH1 fragments revealed that its N-terminus is sufficient for interaction with hMutSα (Fig. 11). Based on considerations of crystal structures of MutL, the area between the loops L45 has been suggested to serve as interaction interface for MutS (Fig. 11) (44). The finding that hMLH1Δ9/10 fails to interact suggests that exons 9 and 10 may incorporate a domain essential for complex formation. Although this deletion is distant from the loops that are homologous to L45, it does not disqualify this area as interaction transmitter, since it was also observed that formation of this interface depends on both nucleotide binding and N-terminal dimerisation (44). Both functions are likely abolished in hMLH1Δ9/10.

Figure 11.

Diagram of the hMLH1 constructs. In the top diagram, the hMLH1 protein is shown with its functional domains as known to date. Numbers refer to amino acid positions. hMLH1 encodes a protein of 756 amino acids including a highly conserved N-terminal ATPase domain (‘ATPase domain’) as well as a variant C-terminal domain (‘PMS interaction domain’), which has been suggested to confer dimerisation with hPMS1 and hPMS2 (56). The ATPase domain also incorporates the conserved loops L45, which have been suggested to contain the MutS–MutL interaction interface in bacterial MMR (44). The diagrams below show the localisation of the hMLH1 fragments LN56 and LC49 as well as the hMLH1 Δ9/10 protein in comparison to the full-length protein. Right: +, interaction; –, no interaction.

Since the N-terminus incorporates the ATPase domain as well as the hMutSα–hMutLα interaction domain, it is possible that the interaction may alter ATP processing by hMutLα, thus accomplishing signal transduction from hMutSα over hMutLα to downstream proteins.

If it is true that interaction and ATP processing of hMutLα are closely coupled, deletions in the ATPase domain may abolish interaction even while a putative interaction interface still is present. Another aspect complicates the precise localisation of the interacting region: as recently shown, the hMutSα–hMutL interaction is DNA length dependent and fails on short DNA substrates (27,30,31). Additionally, MutL proteins bind single- and double-stranded DNA (27,28,58) and contain putative DNA binding domains within their N-terminal halves (25,44). This is supported by our finding that LC49 did not show even basic binding to the DNA substrate. These observations strongly suggest that hMutSα–hMutLα interaction depends on DNA binding by hMutLα (27,30). Assuming that DNA binding by hMutLα is a precondition for complex formation, mutational inactivation of either the interaction interface or the DNA binding activity may result in an interaction failure. Further studies will be necessary to disentangle the mutual influences of hMLH1 domains concerned with DNA binding, ATP processing and hMutSα interaction.

We have recently demonstrated that both hMutLα and hMutLβ interact with hMutSα on DNA in an ATP-dependent manner (27). hMutLβ could not be attributed with a role in in vitro MMR (39), and its putative contribution to HNPCC (59) has recently been refuted (60). The findings of the present study show that hMutSα nonetheless strongly recruits hMutLβ in the absence of hMutLα. Furthermore, hPMS1 has an intrinsic ability to bind hMutSα (which is, although being much weaker than that of hMLH1, stronger than that of hPMS2), suggesting a biological significance of this interaction. When both hMutL heterodimers are present, they may either together form quaternary complexes with hMutSα and DNA or distinct ternary complexes. Since both hMutL heterodimers bind predominantly by their hMLH1 subunit, it is likely that both heterodimers compete for binding to hMutSα. Further studies need to examine how many hMLH1 binding sites the hMutSα heterodimer has.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Marc Wormek and Nicole Weber for their assistance in the performance of the experiments. This work was in part supported by research grant F15/99 from the University of Frankfurt to J.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jiricny J. (1998) Replication errors: cha(lle)nging the genome. EMBO J., 17, 6427–6436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marti T.M., Kunz,C. and Fleck,O. (2002) DNA mismatch repair and mutation avoidance pathways. J. Cell. Physiol., 191, 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modrich P. (1997) Strand-specific mismatch repair in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 24727–24730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltomaki P. (2001) DNA mismatch repair and cancer. Mutat. Res., 488, 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch H.T. (1999) Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 86, 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papadopoulos N. and Lindblom,A. (1997) Molecular basis of HNPCC: mutations of MMR genes. Hum. Mutat., 10, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raedle J., Trojan,J., Brieger,A., Weber,N., Schafer,D., Plotz,G., Staib-Sebler,E., Kriener,S., Lorenz,M. and Zeuzem,S. (2001) Bethesda guidelines: relation to microsatellite instability and MLH1 promoter methylation in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann. Intern. Med., 135, 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu A.L., Welsh,K., Clark,S., Su,S.S. and Modrich,P. (1984) Repair of DNA base-pair mismatches in extracts of Escherichia coli. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol., 49, 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes J. Jr, Clark,S. and Modrich,P. (1990) Strand-specific mismatch correction in nuclear extracts of human and Drosophila melanogaster cell lines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 5837–5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su S.S. and Modrich,P. (1986) Escherichia coli mutS-encoded protein binds to mismatched DNA base pairs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 5057–5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishel R., Ewel,A. and Lescoe,M.K. (1994) Purified human MSH2 protein binds to DNA containing mismatched nucleotides. Cancer Res., 54, 5539–5542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alani E., Chi,N.W. and Kolodner,R. (1995) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2 protein specifically binds to duplex oligonucleotides containing mismatched DNA base pairs and insertions. Genes Dev., 9, 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palombo F., Gallinari,P., Iaccarino,I., Lettieri,T., Hughes,M., D’Arrigo,A., Truong,O., Hsuan,J.J. and Jiricny,J. (1995) GTBP, a 160-kilodalton protein essential for mismatch-binding activity in human cells. Science, 268, 1912–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjornson K.P., Allen,D.J. and Modrich,P. (2000) Modulation of MutS ATP hydrolysis by DNA cofactors. Biochemistry, 39, 3176–3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackwell L.J., Bjornson,K.P. and Modrich,P. (1998) DNA-dependent activation of the hMutSalpha ATPase. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32049–32054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alani E., Sokolsky,T., Studamire,B., Miret,J.J. and Lahue,R.S. (1997) Genetic and biochemical analysis of Msh2p-Msh6p: role of ATP hydrolysis and Msh2p-Msh6p subunit interactions in mismatch base pair recognition. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 2436–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen D.J., Makhov,A., Grilley,M., Taylor,J., Thresher,R., Modrich,P. and Griffith,J.D. (1997) MutS mediates heteroduplex loop formation by a translocation mechanism. EMBO J., 16, 4467–4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackwell L.J., Martik,D., Bjornson,K.P., Bjornson,E.S. and Modrich,P. (1998) Nucleotide-promoted release of hMutSalpha from heteroduplex DNA is consistent with an ATP-dependent translocation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 32055–32062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gradia S., Subramanian,D., Wilson,T., Acharya,S., Makhov,A., Griffith,J. and Fishel,R. (1999) hMSH2-hMSH6 forms a hydrolysis-independent sliding clamp on mismatched DNA. Mol. Cell, 3, 255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iaccarino I., Marra,G., Dufner,P. and Jiricny,J. (2000) Mutation in the magnesium binding site of hMSH6 disables the hMutSalpha sliding clamp from translocating along DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 2080–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishel R. (1998) Mismatch repair, molecular switches and signal transduction. Genes Dev., 12, 2096–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gradia S., Acharya,S. and Fishel,R. (1997) The human mismatch recognition complex hMSH2-hMSH6 functions as a novel molecular switch. Cell, 91, 995–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junop M.S., Obmolova,G., Rausch,K., Hsieh,P. and Yang,W. (2001) Composite active site of an ABC ATPase: MutS uses ATP to verify mismatch recognition and authorize DNA repair. Mol. Cell, 7, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schofield M.J., Nayak,S., Scott,T.H., Du,C. and Hsieh,P. (2001) Interaction of Escherichia coli MutS and MutL at a DNA mismatch. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 28291–28299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ban C. and Yang,W. (1998) Crystal structure and ATPase activity of MutL: implications for DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell, 95, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomer G., Buermeyer,A.B., Nguyen,M.M. and Liskay,R.M. (2002) Contribution of human mlh1 and pms2 ATPase activities to DNA mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 21801–21809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plotz G., Raedle,J., Brieger,A., Trojan,J. and Zeuzem,S. (2002) hMutSalpha forms an ATP-dependent complex with hMutLalpha and hMutLbeta on DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 711–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drotschmann K., Hall,M.C., Shcherbakova,P.V., Wang,H., Erie,D.A., Brownewell,F.R., Kool,E.T. and Kunkel,T.A. (2002) DNA binding properties of the yeast Msh2-Msh6 and Mlh1-Pms1 heterodimers. Biol. Chem., 383, 969–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall M.C., Wang,H., Erie,D.A. and Kunkel,T.A. (2001) High affinity cooperative DNA binding by the yeast Mlh1-Pms1 heterodimer. J. Mol. Biol., 312, 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackwell L.J., Wang,S. and Modrich,P. (2001) DNA chain length dependence of formation and dynamics of hMutSalpha.hMutLalpha.heteroduplex complexes. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 33233–33240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raschle M., Dufner,P., Marra,G. and Jiricny,J. (2002) Mutations within the hMLH1 and hPMS2 subunits of the human MutLalpha mismatch repair factor affect its ATPase activity, but not its ability to interact with hMutSalpha. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 21810–21820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tran P.T. and Liskay,R.M. (2000) Functional studies on the candidate ATPase domains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MutLalpha. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 6390–6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spampinato C. and Modrich,P. (2000) The MutL ATPase is required for mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 9863–9869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall M.C., Shcherbakova,P.V. and Kunkel,T.A. (2002) Differential ATP binding and intrinsic ATP hydrolysis by amino-terminal domains of the yeast Mlh1 and Pms1 proteins. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 3673–3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Au K.G., Welsh,K. and Modrich,P. (1992) Initiation of methyl-directed mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 12142–12148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall M.C., Jordan,J.R. and Matson,S.W. (1998) Evidence for a physical interaction between the Escherichia coli methyl-directed mismatch repair proteins MutL and UvrD. EMBO J., 17, 1535–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall M.C. and Matson,S.W. (1999) The Escherichia coli MutL protein physically interacts with MutH and stimulates the MutH-associated endonuclease activity. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 1306–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang W. (2000) Structure and function of mismatch repair proteins. Mutat. Res., 460, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raschle M., Marra,G., Nystrom-Lahti,M., Schar,P. and Jiricny,J. (1999) Identification of hMutLbeta, a heterodimer of hMLH1 and hPMS1. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 32368–32375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bronner C.E., Baker,S.M., Morrison,P.T., Warren,G., Smith,L.G., Lescoe,M.K., Kane,M., Earabino,C., Lipford,J., Lindblom,A. et al. (1994) Mutation in the DNA mismatch repair gene homologue hMLH1 is associated with hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer. Nature, 368, 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J. and Russel,D.W. (2001) Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, NY.

- 42.Trojan J., Zeuzem,S., Randolph,A., Hemmerle,C., Brieger,A., Raedle,J., Plotz,G., Jiricny,J. and Marra,G. (2002) Functional analysis of hMLH1 variants and HNPCC-related mutations using a human expression system. Gastroenterology, 122, 211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu L., Hong,Y., McCulloch,S., Watanabe,H. and Li,G.M. (1998) ATP-dependent interaction of human mismatch repair proteins and dual role of PCNA in mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 1173–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ban C., Junop,M. and Yang,W. (1999) Transformation of MutL by ATP binding and hydrolysis: a switch in DNA mismatch repair. Cell, 97, 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung W.K., Kim,J.J., Wu,L., Sepulveda,J.L. and Sepulveda,A.R. (2000) Identification of a second MutL DNA mismatch repair complex (hPMS1 and hMLH1) in human epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 15728–15732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brieger A., Trojan,J., Raedle,J., Plotz,G. and Zeuzem,S. (2002) Transient mismatch repair gene transfection for functional analysis of genetic hMLH1 and hMSH2 variants. Gut, 51, 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang D.K., Ricciardiello,L., Goel,A., Chang,C.L. and Boland,C.R. (2000) Steady-state regulation of the human DNA mismatch repair system. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 18424–18431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu B., Parsons,R., Papadopoulos,N., Nicolaides,N.C., Lynch,H.T., Watson,P., Jass,J.R., Dunlop,M., Wyllie,A., Peltomaki,P. et al. (1996) Analysis of mismatch repair genes in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer patients. Nature Med., 2, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kohonen-Corish M., Ross,V.L., Doe,W.F., Kool,D.A., Edkins,E., Faragher,I., Wijnen,J., Khan,P.M., Macrae,F. and St John,D.J. (1996) RNA-based mutation screening in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 59, 818–824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hutter P., Couturier,A., Membrez,V., Joris,F., Sappino,A.P. and Chappuis,P.O. (1998) Excess of hMLH1 germline mutations in Swiss families with hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer, 78, 680–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charbonnier F., Martin,C., Scotte,M., Sibert,L., Moreau,V. and Frebourg,T. (1995) Alternative splicing of MLH1 messenger RNA in human normal cells. Cancer Res., 55, 1839–1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Genuardi M., Viel,A., Bonora,D., Capozzi,E., Bellacosa,A., Leonardi,F., Valle,R., Ventura,A., Pedroni,M., Boiocchi,M. et al. (1998) Characterization of MLH1 and MSH2 alternative splicing and its relevance to molecular testing of colorectal cancer susceptibility. Hum. Genet., 102, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Galio L., Bouquet,C. and Brooks,P. (1999) ATP hydrolysis-dependent formation of a dynamic ternary nucleoprotein complex with MutS and MutL. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2325–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bowers J., Tran,P.T., Joshi,A., Liskay,R.M. and Alani,E. (2001) MSH-MLH complexes formed at a DNA mismatch are disrupted by the PCNA sliding clamp. J. Mol. Biol., 306, 957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Habraken Y., Sung,P., Prakash,L. and Prakash,S. (1998) ATP-dependent assembly of a ternary complex consisting of a DNA mismatch and the yeast MSH2-MSH6 and MLH1-PMS1 protein complexes. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 9837–9841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guerrette S., Acharya,S. and Fishel,R. (1999) The interaction of the human MutL homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 6336–6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kondo E., Horii,A. and Fukushige,S. (2001) The interacting domains of three MutL heterodimers in man: hMLH1 interacts with 36 homologous amino acid residues within hMLH3, hPMS1 and hPMS2. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1695–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bende S.M. and Grafstrom,R.H. (1991) The DNA binding properties of the MutL protein isolated from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 1549–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicolaides N.C., Papadopoulos,N., Liu,B., Wei,Y.F., Carter,K.C., Ruben,S.M., Rosen,C.A., Haseltine,W.A., Fleischmann,R.D., Fraser,C.M. et al. (1994) Mutations of two PMS homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Nature, 371, 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu T., Yan,H., Kuismanen,S., Percesepe,A., Bisgaard,M.L., Pedroni,M., Benatti,P., Kinzler,K.W., Vogelstein,B., Ponz de Leon,M. et al. (2001) The role of hPMS1 and hPMS2 in predisposing to colorectal cancer. Cancer Res., 61, 7798–7802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]