Abstract

Despite recent progress in elucidating the regulation of methionine (Met) synthesis, little is known about the catabolism of this amino acid in plants. In this article, we present several lines of evidence indicating that the cleavage of Met catalyzed by Met γ-lyase is the first step in this process. First, we cloned an Arabidopsis cDNA coding a functional Met γ-lyase (AtMGL), a cytosolic enzyme catalyzing the conversion of Met into methanethiol, α-ketobutyrate, and ammonia. AtMGL is present in all of the Arabidopsis organs and tissues analyzed, except in quiescent dry mature seeds, thus suggesting that AtMGL is involved in the regulation of Met homeostasis in various situations. Also, we demonstrated that the expression of AtMGL was induced in Arabidopsis cells in response to high Met levels, probably to bypass the elevated Km of the enzyme for Met. Second, [13C]-NMR profiling of Arabidopsis cells fed with [13C]Met allowed us to identify labeled S-adenosylmethionine, S-methylmethionine, S-methylcysteine (SMC), and isoleucine (Ile). The unexpected production of SMC and Ile was directly associated to the function of Met γ-lyase. Indeed, we showed that part of the methanethiol produced during Met cleavage could react with an activated form of serine to produce SMC. The second product of Met cleavage, α-ketobutyrate, entered the pathway of Ile synthesis in plastids. Together, these data indicate that Met catabolism in Arabidopsis cells is initiated by a γ-cleavage process and can result in the formation of the essential amino acid Ile and a potential storage form for sulfide or methyl groups, SMC.

Keywords: methionine γ-lyase, NMR profiling, plant

The sulfur-containing amino acid methionine (Met) is an essential metabolite in all living organisms (1). Besides its role as protein constituent, Met is the precursor of S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), which is the major methyl-group donor in transmethylation reactions and an intermediate in the biosynthesis of biotin, polyamines, and the phytohormone ethylene. Met is synthesized de novo by plants, fungi, and microbes. It is the only sulfur-containing amino acid that is essential for human and monogastric livestock. In these organisms, Met is metabolized through the reverse transsulfuration pathway where the γ-cleavage of the cystathionine intermediate, a reaction that does not exist in plants, allows synthesis of cysteine (Cys) (2). Therefore, Met must be supplied from the diet and, because it is the most limiting essential amino acid in legume seeds, metabolic engineering strategies have been developed to increase the carbon flux into free Met as well as the incorporation of this amino acid into proteins (3).

In higher plants, the neo-synthesized Met molecule originates from three convergent pathways with the sulfur atom deriving from Cys, the nitrogen/carbon backbone from aspartate, and the methyl moiety from the β-carbon of serine via the pool of folates (1). De novo Met synthesis consists of three consecutive reactions localized in plastids (4) and catalyzed by cystathionine γ-synthase, cystathionine β-lyase, and methionine synthase. Several recent studies have indicated that Met synthesis and accumulation are subject to complex regulatory controls in which cystathionine γ-synthase plays a crucial role (5–7).

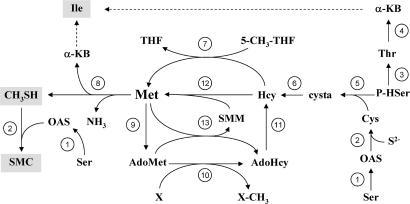

Studies of metabolic fates of Met using the aquatic plant Lemna paucicostata indicated that the synthesis and turnover of AdoMet accounts for ≈80% of Met metabolism, whereas the synthesis of proteins drives ≈20% of Met (for a review, see ref. 8). More than 90% of AdoMet then is used for transmethylation, leading to nucleic acid, protein, lipid, and other metabolites modifications. The resulting homocysteinyl moiety is recycled back to Met and AdoMet by a set of cytosolic reactions designated as the activated methyl cycle. The use of AdoMet for the synthesis of polyamines and, in some plant tissues, ethylene also is accompanied by recycling of the methylthio moiety and regeneration of Met. The last known metabolic fate of Met is unique to plants and leads to the production of S-methylmethionine (SMM), a compound resulting from the AdoMet-dependent methylation of Met. SMM then can donate a methyl group to homocysteine (Hcy) through the reaction catalyzed by Hcy S-methyltransferase, yielding two molecules of Met. The SMM cycle might serve to achieve short-term control of AdoMet levels in plant cells, thus controlling the commitment of one-carbon units into methyl-group synthesis (9–11).

Despite recent progress in elucidating the synthesis of Met and its complex regulation, little is known about the catabolism of this amino acid in plant cells. Several authors have reported that plants or plant tissues emit volatile sulfur-containing compounds such as methanethiol, dimethyl disulfide, or dimethyl sulfide as a consequence of the accumulation of free Met (6, 12, 13). The process responsible for the production of these volatiles and its physiological significance are still unknown.

In this study, we have cloned an Arabidopsis cDNA coding a functional Met γ-lyase (MGL), an enzyme catalyzing the γ-cleavage of Met into methanethiol, α-ketobutyrate (αKB), and ammonia. The metabolic role of this enzyme was analyzed in Arabidopsis cells by using [13C]Met and NMR. Beside the accumulation of Met, AdoMet, and SMM, we also identified unequivocally two major metabolites deriving from the catabolism of Met, namely S-methylcysteine (SMC) and isoleucine (Ile). We present here several lines of evidence indicating that the γ-cleavage of Met into ammonia, αKB, and methanethiol is the first event that leads to the formation of these two compounds.

Results

Cloning and Biochemical Characterization of MGL from Arabidopsis.

In various microorganisms and in primitive protozoa (Entamoeba histolytica and Trichomonas vaginalis), Met catabolism is initiated by the γ-cleavage of the molecule (14–17). This reaction is catalyzed by MGL and leads to the formation of αKB, ammonia, and methanethiol (CH3SH). Searches of the Arabidopsis genome for homologs of bacterial MGL detected a small set of genes encoding pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzymes involved in Met/Cys metabolism. The three best hits of the BlastP searches were cystathionine-γ-synthase (At3g01120), cystathionine-β-lyase (At3g57050), and a putative cystathionine-γ-synthase enzyme (At1g33320) for which there is no corresponding EST or full-length cDNA, thus suggesting a pseudogene. The fourth hit corresponded to the At1g64660 gene encoding a predicted protein with 28% to 32% identity (48% similarity) with MGL from Pseudomonas putida and E. histolytica, respectively.

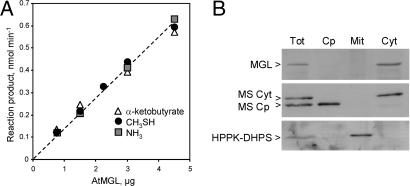

To determine whether the At1g64660 protein is a functional MGL, the full-length coding sequence was cloned into the Escherichia coli expression plasmid pET20b(+), allowing production of a recombinant protein with a C-terminal His tag. The purified recombinant protein exhibited a characteristic absorption peak at 420 nm observed for pyridoxal phosphate-containing enzymes. To investigate the MGL activity catalyzed by At1g64660, we used three assays allowing determination of the three products released during the γ-elimination of Met. As shown in Fig. 1A, equal amounts of CH3SH, NH3, and αKB were detected, demonstrating that the protein has an MGL activity and may therefore be termed AtMGL. The recombinant AtMGL obeyed Michaelis–Menten kinetics with a Km value for Met of 10.6 ± 0.9 mM. This value is elevated but compares well with those determined for other MGL enzymes (0.9–10 mM) (15–17). Together these data indicate that the At1g64660 gene encodes a functional MGL in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 1.

Biochemical characterization of MGL from Arabidopsis. (A) Steady-state analysis of the recombinant AtMGL reaction products. Enzyme activity was measured at 30°C by using three assays to determine CH3SH, NH3, and αKB produced during Met cleavage. The specific activity of AtMGL was 340 ± 40 nmol·min−1·mg−1 of protein. (B) Subcellular localization of MGL in Arabidopsis. Soluble proteins (20 μg per lane) from a total cell extract (Tot), purified chloroplasts (Cp), purified mitochondria (Mit), and a cytosolic-enriched fraction (Cyt) were analyzed by Western blot analysis with polyclonal antibodies raised against AtMGL. The polypeptide detected with the AtMGL serum was 48 ± 1 kDa. Antibodies against Arabidopsis methionine synthase isoforms (cytosolic and chloroplastic polypeptides at 84 and 81 kDa, respectively) and pea hydroxymethyl dihydropterin pyrophosphokinase/dihydropteroate synthase (HPPK-DHPS; mitochondrial marker) were used to analyze cross-contaminations between subfractions (4, 35).

The At1g64660 cDNA encodes a 441-residue protein with a predicted molecular mass of 47,820 Da. The deduced protein sequence did not show any predictable targeting signal, suggesting a cytosolic location of AtMGL. To verify this prediction, we raised polyclonal antibodies against recombinant AtMGL and analyzed the subcellular distribution of the enzyme by Western blotting using chloroplasts, mitochondria, and a cytosolic enriched fraction purified from Arabidopsis cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, Arabidopsis MGL is a 48 ± 1 kDa enzyme located in the cytosol.

NMR Profiling of Met Metabolism in Arabidopsis Cells.

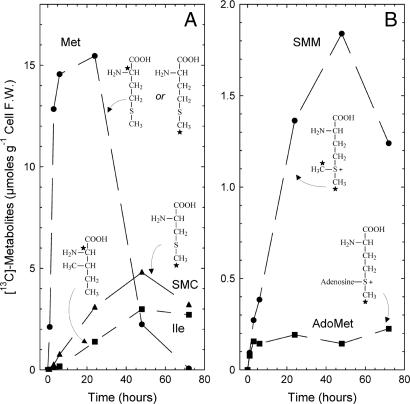

Metabolic profiling of Met metabolism was performed by using Arabidopsis cells fed with 2 mM [13C2]Met or [13C5]Met. As shown in Fig. 2A, the intracellular Met concentration increased rapidly [maximal uptake rate ≈5 μmol·h−1·g−1 fresh weight (FW)] to reach a maximal value after 24 h of incubation. At that time, all of the exogenous Met had been taken up, and the intracellular Met concentration was ≈500-fold higher than in control cells (20–30 nmol·g−1 FW). Then, the intracellular Met concentration started to rapidly decline, indicating a fast metabolism. From [13C5]Met feeding experiments, we were able to identify [13C5]SMM, [13C5′]SMM, and [13C5]AdoMet. In contrast to Met, AdoMet concentration quickly reached a plateau value (0.15–0.25 μmol·g−1 FW) after 3 h of incubation (Fig. 2B). Because control cells contained 20 ± 5 nmol AdoMet g−1 FW, these data indicated a 10-fold increase in AdoMet concentration after Met addition. This rapid increase followed by the steady value reflects the high turnover of AdoMet through the methyl cycle activity in the cytosol (4) and a tight control of the pool. Also, the unique capacity that plants have to transfer a methyl group from AdoMet to Met (9, 10) is illustrated by the accumulation of SMM in Arabidopsis cells (Fig. 2B). Indeed, although SMM concentration was too low to be determined in control cells, this compound reached a maximal value of ≈2 μmol·g−1 FW after 48 h of incubation with Met. These data are in accordance with the assumption that the SMM cycle in plants serves to prevent accumulation of AdoMet (10).

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of Met incorporation and metabolism in Arabidopsis cells. Cells were fed with either 2 mM [13C2]Met or 2 mM [13C5]Met and harvested at the indicated time intervals, and perchloric acid extracts were analyzed by [13C]-NMR. The accumulation of Met, SMC, and Ile is shown in A and that of SMM and AdoMet is shown in B.

In addition to AdoMet and SMM, our experiments revealed previously unsuspected metabolites deriving from Met. Indeed, feeding experiments with either [13C2]Met or [13C5]Met revealed peaks corresponding to [13C2]isoleucine (Ile) and [13C4]S-methylcysteine (SMC), respectively (Fig. 2A). The time-course accumulation of these compounds differed from that of AdoMet or SMM because Ile and SMC could not be detected during the first 3–6 h of incubation with Met. The Ile concentration was ≈0.15 μmol·g−1 FW in control cells and increased by 20-fold after 48 h of incubation with Met. Ile is an essential branched chain amino acid synthesized from threonine (18). The first intermediate of this pathway is αKB, a compound formed through a reaction catalyzed by threonine deaminase. SMC was not detectable in control cells before the addition of Met. This compound has been measured in relatively large amounts in several legume seeds but could not be detected as a product of sulfur assimilation in other plant species (2). The biosynthetic route for this compound is unclear; SMC can be formed by the methylation of Cys using AdoMet or SMM as a methyl group donor or by a side reaction catalyzed by O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase in the presence of O-acetylserine and CH3SH (2).

Our feeding experiments with Met were systematically associated with a characteristic smell, typical of sulfur-containing molecules. The use of [35S]Met and [14C5]Met indicated that the volatile compounds emitted by cells derived from both the sulfur and the methyl group of Met. These data suggested that Arabidopsis cells accumulating Met emitted CH3SH and, most probably, its oxidative form dimethyl disulfide (CH3SSCH3), as previously observed for other plants with an altered Met metabolism (12, 13).

Met Catabolism in Arabidopsis Cells Is Initiated by a γ-Cleavage Process.

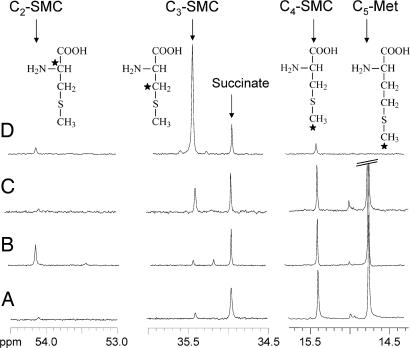

The data presented above indicate that the catabolism of Met in Arabidopsis cells is associated with the formation of Ile and SMC. Also, the γ-cleavage of Met results in αKB, NH3, and CH3SH production. It is thus possible that αKB serves as a precursor for Ile synthesis and that CH3SH reacts with O-acetylserine, an activated form of serine (Ser), to produce SMC. To test this possibility, we followed the catabolism of [13C5]Met in the presence of either [13C2]Ser or [13C3]Ser. As shown in Fig. 3, we could observe, in addition to [13C4]SMC that derives from [13C5]Met, peaks corresponding to [13C2]SMC or [13C3]SMC when [13C2]Ser or [13C3]Ser were added in the medium, respectively. This dual-labeling of SMC clearly indicated that this molecule was produced from the nitrogen/carbon skeleton of Ser and the methyl group of Met. In addition, when Arabidopsis cells were cultivated for 24 h in the presence of [13C3]Ser and CH3SH (no addition of Met), a resonance corresponding to [13C3]SMC was detected (Fig. 3D). This peak was not visible in the absence of CH3SH (data not shown). This result indicates that CH3SH diffused within the cells and could directly react with the acetylated derivative of Ser to generate SMC.

Fig. 3.

Representative in vitro [13C]-NMR spectra showing SMC synthesis in Arabidopsis cells. Perchloric acid extracts were prepared from cells incubated for 24 h in the presence of the compounds indicated below and analyzed by [13C]-NMR. Magnifications of the resonance peaks of C2, C3, and C4 of SMC are shown. Cells were grown in the presence of 2 mM [13C5]Met (A); 2 mM [13C5]Met plus 0.5 mM [13C2]Ser (B); 2 mM [13C5]Met plus 0.5 mM [13C3]Ser (C); and 2 mM [13C3]Ser plus 2 mM CH3SH (D). The amount of SMC produced was 3.1–3.4 μmol·g−1 FW in experiments A–C and 5.9 μmol·g−1 FW in experiment D.

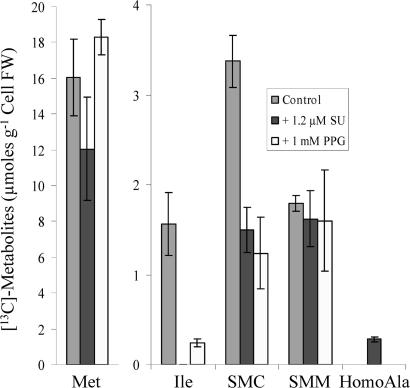

The synthesis of Ile is blocked by sulfonylurea such as methyl sulfometuron, a potent inhibitor of acetohydroxy acid synthase, the enzyme catalyzing the second step in the pathway (19). In the presence of this inhibitor, the catabolism of Met in Arabidopsis cells was not associated anymore with the production of Ile, as expected (Fig. 4). In addition, SMC was still produced, although in a lower amount, indicating that the γ-cleavage reaction of Met still occurred. Because the substrate of acetohydroxy acid synthase is αKB, it was logical to think that this compound should accumulate in the presence of sulfonylurea. This result was not the case, but we detected small amount of α-aminobutyrate (homoalanine), the transaminated product of αKB (Fig. 4), as already described for plants treated with sulfonylurea (19).

Fig. 4.

Effects of sulfonylurea and propargylglycine on Met catabolism in Arabidopsis cells. Cells were incubated for 24 h in the presence of either 2 mM [13C2]Met or 2 mM [13C5]Met plus either 1.2 μM methyl sulfometuron (sulfonylurea, SU) or 1 mM d,l-propargylglycine (PPG). Perchloric acid extracts were analyzed by [13C]-NMR. The presented results are the average of three distinct experiments ± SD.

MGL belongs to the γ-subfamily of pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzymes and, like the other members of this family, is inhibited by propargylglycine (14, 17). As shown in Fig. 4, the simultaneous feeding of Arabidopsis cells with 2 mM Met and 1 mM propargylglycine resulted in a 3- to 6-fold decrease of Ile and SMC in the treated versus control cells, whereas Met and SMM were not affected. From these data, we can conclude that propargylglycine significantly impaired the γ-cleavage of Met, the first process toward Ile and SMC synthesis.

MGL Expression Is Induced by High Met Concentration.

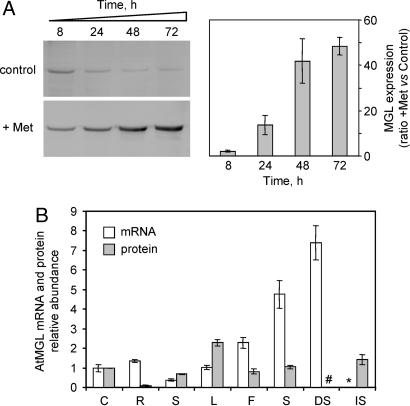

Identification of MGL as the first enzyme involved in Met degradation in Arabidopsis cells raises the question of the physiological function of this catabolic route. Indeed, the apparent Km of AtMGL for Met was high (≈10 mM), and the amount of free Met in Arabidopsis cells grown under standard conditions was 25 ± 5 nmol·g−1 FW. Assuming that all intracellular Met is located in the cytoplasm, we estimated that the cytoplasmic concentration is not >150–200 μM, which is 50 times lower than the Km value measured for the recombinant enzyme. This finding, together with the 3–6 h lag phase needed for the onset of SMC and Ile production (Fig. 2A), suggested that this catabolic pathway operates preferentially when Met has accumulated above a certain value in the cytoplasm. Western blots shown in Fig. 5A indicated that MGL was expressed under standard growth conditions and was strongly induced in Arabidopsis cells accumulating Met. Indeed, although the amount of MGL gradually decreased in control cells during the growth phase, the addition of 2 mM Met in the culture medium resulted in a strong induction (up to 40-fold) of the enzyme (Fig. 5A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the AtMGL mRNA steady-state level indicated that the induction of the protein in Met-treated cells was not associated with transcript accumulation (data not shown), thus suggesting a posttranscriptional control of the amount of the enzyme.

Fig. 5.

MGL expression patterns in response to Met and in different Arabidopsis organs. (A) MGL protein expression in Arabidopsis cells treated or not treated with 2 mM Met. Total soluble proteins (20 μg per lane) were analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against AtMGL. At each time point, the ratio between MGL levels in treated versus control cells was measured by using the ECL Plus Western Blotting detection reagents and a Typhoon 9400 scanner (data are means ± SD from two independent cell cultures). (B) AtMGL mRNA and protein expression levels in Arabidopsis organs. Protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting as described above: cell suspension cultures (C), roots (R), stems (S), rosette leaves (L), flowers (F), siliques (S), dry mature seeds (DS), and seeds imbibed with water for 24 h at 4°C (IS). Steady-state AtMGL (At1g64660) mRNA levels were obtained from the Arabidopsis microarray database Genevestigator (www.genevestigator.ethz.ch). The protein and mRNA levels relative abundances were referred to the expression found in cell suspension cultures. #, no detectable protein; ∗, no data available from the microarray database.

To further address the physiological function of MGL in planta, we compared the expression pattern of the enzyme (as determined by Western blot analysis) with microarray data available in the Arabidopsis Genevestigator database (20). As shown in Fig. 5B, the MGL protein is present at different levels in all examined organs, except in dry mature seeds where the protein could not been detected. There is no direct correlation between the accumulation of the AtMGL protein and the corresponding transcript. For example, rosette leaves exhibit a low level of the AtMGL mRNA but the highest amount of the protein, and, contrarily, the highest transcript level found in dry seeds is not accompanied by the accumulation of the enzyme. Also, the AtMGL protein is highly expressed in imbibed seeds, suggesting that transcript accumulation at the dry mature stage is a prerequisite for a rapid production of MGL during the imbibition process. The discrepancy between mRNA and protein levels could not be correlated to any particular status of free Met in the different plant organs, which contain comparable amounts of free Met (20–70 nmol·g−1 FW) (21). Together these data suggest that MGL could participate in the regulation of Met homeostasis in all plant organs and could play an important role in the resumption of cell metabolism during germination.

Discussion

Because of the central position of Met in many cellular processes, the homeostasis of this amino acid must be tightly controlled. The main reactions involved in the synthesis, utilization, and degradation of Met in higher plants are summarized in Fig. 6. The production of SMM through the AdoMet-dependent methylation of Met has been proposed to achieve short-term control of AdoMet level and to function as a storage or transport form of Met when this amino acid is present in excess (9–11). Our results corroborate these findings because Arabidopsis cells that accumulate elevated amounts of Met are able to maintain a low and steady concentration of AdoMet while they accumulate large amounts of SMM. The accumulation of this compound cannot deal, however, with a large excess of Met, possibly because of the energy cost of the synthesis (one ATP per SMM molecule), and Met must be removed through other ways. From our data, we could estimated the metabolic fate of incorporated Met as follows: after 24 h of incubation, 45% of Met taken up from the medium was recovered as free Met, 5% was converted to SMM, and 40% was cleaved to produce CH3SH, NH3, and αKB (the remaining 10% could not be determined by NMR and could correspond, in part, to Met incorporated into proteins). Most of CH3SH produced by the γ-cleavage of Met was released from the cells as a volatile compound, whereas 25% was used for the production of SMC.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of Met metabolism in Arabidopsis. Compounds resulting from the γ-cleavage of Met are indicated in gray frames. 1, serine acetyltransferase; 2, O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase; 3, threonine synthase; 4, threonine deaminase; 5, cystathionine-γ-synthase; 6, cystathionine-β-lyase; 7, Met synthase; 8, MGL; 9, AdoMet synthetase; 10, methyltransferases; 11, AdoHcy hydrolase; 12, Hcy S-methyltransferase; 13, AdoMet:Met S-methyltransferase. cysta, cystathionine; OAS, O-acetylserine; P-HSer, O-phosphohomoserine; 5-CH3-THF, 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate; THF, tetrahydrofolate; Thr, threonine.

Two pathways leading to Met catabolism have been described. The first route is initiated by transamination of Met, forming 4-methylthio-2-oxobutyric acid (KMBA). It has been characterized in a variety of animals (22), in yeasts (23, 24), and in Lactococcus lactis (25). [13C]-NMR studies performed in yeast cells indicated that KMBA was mainly decarboxylated then reduced to produce methionol or, in a lower extent, cleaved by a demethiolase activity to produce CH3SH and αKB. Neither SMC nor Ile were detected in these experiments. In our studies, we could not detect the production of KMBA or methionol, thus indicating that the catabolism of Met in Arabidopsis cells is not initiated by a transaminase activity. Our results indicate that Met degradation in Arabidopsis cells is initiated by a γ-cleavage of the molecule, producing NH3, CH3SH, and αKB. This second route is initiated by MGL (EC 4.4.1.11), a pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzyme also found in some microorganisms (14–17).

In Arabidopsis, MGL is a cytosolic enzyme encoded by the At1g64660 gene. MGL is present in Arabidopsis cells grown under standard conditions and in all analyzed organs, except in quiescent dry mature seeds, thus suggesting that this enzyme probably is involved in the regulation of Met homeostasis in various situations. In seeds, the MGL protein synthesis is strongly induced during the imbibition period from a pool of preexisting mRNA. These data suggest an important role of the enzyme in the germination process. If this hypothesis holds true, metabolic engineering strategies of the Met γ-cleavage reaction is a promising way to produce seeds with an improved Met content. Also, we demonstrated that the MGL protein accumulated when the intracellular level of free Met has reached an elevated concentration (10–15 mM). Likewise, it was shown that the previously unknown enzymatic system that degrades Met in pumpkin leaf discs was induced by Met (13). The induction of MGL expression in plant tissues in response to high Met levels is possibly a response to bypass the elevated Km of the enzyme for Met (≈10 mM).

It was previously shown that plants that accumulate high concentrations of soluble Met were characterized by the emission of CH3SH and dimethyl disulfide (12, 13). Our feeding experiments with Met, Ser, and CH3SH (Fig. 3) indicated that part of CH3SH could be condensed to an activated Ser molecule to form SMC. This reaction likely involved O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase, an enzyme that normally condenses O-acetylserine with sulfide to produce Cys and acetate (2). Indeed, in support to our in vivo data, in vitro experiments previously showed that plant O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase has the capacity to form SMC in the presence of O-acetylserine and CH3SH (26). An alternative route for SMC synthesis in Arabidopsis could be envisaged by comparison with selenium (Se) metabolism in Astragalus species. These plants have the ability to hyperaccumulate Se and possess a Se-Cys methyltransferase that catalyzes the synthesis of Se-methylselenocysteine by using either AdoMet or SMM as methyl sources (27). The closest Arabidopsis homologs of the Se-Cys methyltransferase found in Astragalus correspond to the three isoforms of the enzyme Hcy methyltransferase that operates in the SMM cycle (Fig. 6) (10, 28). Because these three isoenzymes have a very poor activity with Cys as substrate and are inhibited by Met, their involvement in the synthesis of SMC is very unlikely. Together these data suggest strongly that Arabidopsis cells do not have the capacity to methylate Cys and that SMC synthesis is caused by a side reaction of O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase in the presence of O-acetylserine and CH3SH.

The physiological significance of SMC production is not known. SMC is present in relatively large amount in the seeds of several legumes, and there are some lines of evidence indicating that SMC is metabolized, with its methyl moiety, at least, being incorporated into the methyl of Met (2). In our experimental conditions, we could not identify metabolites deriving from SMC, but in vivo NMR experiments allowed us to determine that SMC was produced in the cytoplasm and then rapidly transferred to the vacuole (data not shown), thus suggesting a storage role for the molecule. Our NMR profiling data also established that the C2 of Met was recovered as the C2 of Ile, thus indicating that part of αKB produced by the γ-cleavage of Met in the cytosol can be transported to plastids and integrate the Ile biosynthetic pathway. Thus, in situations of excess Met, this γ-cleavage process results in the salvage of the nitrogen/carbon backbone of Met into another essential amino acid, Ile, and in the formation of a potential storage form for sulfide or methyl groups, SMC.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) cell suspension cultures were grown under continuous light (40 μE·m−2·s−1) at 23°C with rotary agitation at 125 rpm in Gamborg's B5 medium supplemented with 1 μM 2-naphtalene acetic acid and 1.5% (wt/vol) sucrose. Cells were subcultured every 7 days, and Met feeding experiments were started the third day of growth. For each NMR determination, cells (8–10 g fresh weight) were kept in a volume of 0.2 liter and stirred continuously at 125 rpm in the presence of the 13C-labeled compound for the required time. 13C-labeled products (99%) were purchased from Leman (Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France), and all other biochemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France).

Perchloric Acid Extracts.

At each time point, 0.2 liter of the cell suspension culture was collected to determine the amount of 13C-labeled compound that had been incorporated within the cells. Cells were washed with distilled water to remove all traces of external 13C-labeled compound, weighed, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder with 0.9 ml of 70% (vol/vol) perchloric acid and 250 μmol of maleate (internal standard). After thawing, the suspension was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min to remove particulate matter, and the supernatant was neutralized with 2 M KHCO3 to approximately pH 5. The supernatant then was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove KClO4; the resulting supernatant was lyophilized, dissolved in 2.5 ml of water containing 10% (vol/vol) D2O, and neutralized to pH 7.5.

NMR Measurements.

Spectra of neutralized perchloric acid extracts were recorded on a Bruker NMR spectrometer (AMX 400, wide bore; Bruker BioSpin, Wissembourg, France) equipped with a 10-mm multinuclear probe tuned at 100.6 MHz for [13C]-NMR studies. The [13C]-NMR acquisition conditions were as described (29). Spectra of standard solutions of known compounds at pH 7.5 were compared with that of perchloric acid extracts of Arabidopsis cells. The definitive assignments were made after running a series of analyses to determine the pH-dependent chemical shift of perchloric acid extracts in which the authentic compound was added (30). The yield of recovery (≈80%) was estimated by adding known amounts of authentic compounds to frozen cells before grinding. The chemical shifts were (in ppm): [13C3]Ser, 61.14; [13C2]Ile, 60.42; [13C2]Met, 54.78; [13C2]SMC, 54.11; [13C3]SMC, 35.33; [13C5]SMM, 25.43; [13C5′]SMM, 25.39; [13C5]AdoMet, 24.07; [13C4]SMC, 15.35; and [13C5]Met, 14.71. Spectra were analyzed with MestReC Lite software (Mestrelab Research, Santiago de Compostela, Spain).

AtMGL cDNA Cloning.

A full-length cDNA coding AtMGL (At1g64660) was obtained by PCR amplification of an A. thaliana (var. Columbia) cDNA library constructed in pYES (31). Primers MGL1 (5′-GAGACATATGGCTCATTTCCTCGAGACAC-3′) and MGL2 (5′-GAGAGAATTCATTCTGAGGAATGCTTTCTCG-3′) that overlap the initiation Met codon and the stop codon of At1g64660, respectively, and create NdeI and EcoRI restriction sites (underlined) were used for the cloning of AtMGL into the pET20b(+) expression vector (Novagen, Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). The resulting plasmid, pET-AtMGL, encodes a fusion between the complete ORF of At1g60660 and a C-terminal hexa-histidine tag. The pET-AtMGL construct was introduced first into E. coli DH5α and sequenced on both strands (Genome Express, Meylan, France) and then introduced into E. coli BL21 CodonPlus (DE3) RIL cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Overexpression and Purification of Recombinant AtMGL.

E. coli BL21 cells harboring pET-AtMGL were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing carbenicillin (100 μg·ml−1) until A600 reached 0.6. Isopropylthio-β-d-galactoside was added (0.4 mM), and the cells were grown further for 16 h at 37°C. Cells from 0.5-liter cultures were collected by centrifugation (4,000 × g for 20 min), suspended in 15 ml of buffer A (50 mM KPi, pH 8.0/500 mM NaCl) containing 10 mM imidazole and a mixture of protease inhibitors (no. 1873580; Roche Applied Science, Meylan, France), and then disrupted by sonication. The soluble protein extract was separated from cell debris by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 30 min and applied onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) previously equilibrated with buffer A containing 10 mM imidazole. After successive washes with buffer A supplemented with 10, 30, and 50 mM imidazole, the recombinant protein was eluted with buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. Fractions containing AtMGL were pooled, dialyzed against 20 mM KPi (pH 7.5) and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and concentrated by centrifugation (Microsep, 30 kDa cut-off; Pall Life Sciences, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France).

Assays for MGL.

MGL activity was measured by using three different assays to follow the production of (i) αKB using a coupled assay with lactate dehydrogenase (32); (ii) ammonia using a coupled assay with glutamate dehydrogenase (33); and (iii) CH3SH with 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) (34). Because the last assay was the most sensitive, it was used subsequently for all kinetic determinations. The standard assay mixture contained 50 mM Tricine-Na (pH 7.2), 20 μM pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, 25 mM l-methionine, 0.5–5 μg of AtMGL, and 0.1 mM DTNB in a final volume of 400 μl. The reaction was initiated with the enzyme, and the formation of thiophenolate was monitored continuously at 412 nm (ε412 = 13,600 M−1·cm−1) and 30°C. For the αKB assay DTNB was replaced by lactate dehydrogenase (3.4 units) and NADH (200 μM). The coupling assay for ammonia determination contained glutamate dehydrogenase (4.5 units), αKB (10 mM), and NADH (200 μM). In both assays, the reaction was initiated with the recombinant AtMGL, and the oxidation of NADH was followed at 340 nm and 30°C. The initial velocities were linear for at least 5 min, and rates varied linearly with the enzyme concentration.

Western Blot Analysis.

Total soluble proteins from Arabidopsis cells or plant organs were extracted by grinding powdered samples in 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and a mixture of protease inhibitors. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used as a source of soluble proteins. Chloroplasts and mitochondria were isolated and purified with Percoll gradients as described (4). A cytosolic-enriched fraction was prepared from Arabidopsis protoplasts by using the procedure described in ref. 4. Proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE and electroblotted to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were probed by using AtMGL polyclonal antibodies produced in Guinea pigs (Centre Valbex, Villeurbanne, France), and detection was performed by chemiluminescence. Protein quantification was achieved by using the ECL Plus Western Blotting detection reagents and a Typhoon 9400 scanner (GE Healthcare Europe, Saclay, France).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Elisabeth Gout for wise advices in the analysis of NMR data, Dr. Gilles Curien (Laboratoire de Physiologie Cellulaire Végétale) for gift of the “CGS3” plasmid, and Drs. Renaud Dumas and Claude Alban for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- Met

methionine

- SMC

S-methylcysteine

- AdoMet

S-adenosylmethionine

- SMM

S-methylmethionine

- Hcy

homocysteine

- αKB

α-ketobutyrate

- MGL

Met γ-lyase

- FW

fresh weight

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

References

- 1.Ravanel S, Gakiere B, Job D, Douce R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7805–7812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovanelli J, Mudd SH, Datko AH. In: The Biochemistry of Plants. Miflin BJ, editor. Vol 5. New York: Academic; 1980. pp. 453–487. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galili G, Hofgen R. Metab Eng. 2002;4:3–11. doi: 10.1006/mben.2001.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravanel S, Block MA, Rippert P, Jabrin S, Curien G, Rébeillé F, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22548–22557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curien G, Ravanel S, Dumas R. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:4615–4627. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacham Y, Avraham T, Amir R. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:454–462. doi: 10.1104/pp.010819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Onouchi H, Nagami Y, Haraguchi Y, Nakamoto M, Nishimura Y, Sakurai R, Nagao N, Kawasaki D, Kadokura Y, Naito S. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1799–1810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1317105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giovanelli J. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:419–453. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocsis MG, Ranocha P, Gage DA, Simon ES, Rhodes D, Peel GJ, Mellema S, Saito K, Awazuhara M, Li CJ, et al. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1808–1815. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranocha P, McNeil SD, Ziemak MJ, Li C, Tarczynski MC, Hanson AD. Plant J. 2001;25:575–584. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bourgis F, Roje S, Nuccio ML, Fisher DB, Tarczynski MC, Li C, Herschbach C, Rennenberg H, Pimenta MJ, Shen TL, et al. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1485–1498. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.8.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boerjan W, Bauw G, Van-Montagu M, Inze D. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1401–1414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.10.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt A, Rennenberg H, Wilson LG, Filner P. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:1181–1185. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias B, Weimer B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3327–3331. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3327-3331.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKie AE, Edlind T, Walker J, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5549–5556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka H, Esaki N, Soda K. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1985;7:530–537. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokoro M, Asai T, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T, Nozaki T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42717–42727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh BK. In: Plant Amino Acids. Singh BK, editor. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1999. pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaner DL, Singh BK. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:1221–1226. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann P, Hennig L, Gruissem W. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:407–409. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Lee M, Chalam R, Martin MN, Leustek T, Boerjan W. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:95–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livesey G. Trends Biochem Sci. 1984;9:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arfi K, Landaud S, Bonnarme P. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:2155–2162. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2155-2162.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perpete P, Duthoit O, De Maeyer S, Imray L, Lawton AI, Stavropoulos KE, Gitonga VW, Hewlins MJ, Dickinson JR. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1356.2005.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao S, Mooberry ES, Steele JL. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4670–4675. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4670-4675.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikegami F, Kaneko M, Kamiyama H, Murakoshi I. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:697–701. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuhierl B, Thanbichler M, Lottspeich F, Bock A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5407–5414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ranocha P, Bourgis F, Ziemak MJ, Rhodes D, Gage DA, Hanson AD. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15962–15968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mouillon JM, Ravanel S, Douce R, Rébeillé F. Biochem J. 2002;363:313–319. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gout E, Bligny R, Pascal N, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3986–3992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elledge SJ, Mulligan JT, Ramer SW, Spottswood M, Davis RW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1731–1735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czok R, Lamprecht W. In: Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Bergmeyer H, editor. Vol 3. New York: Academic; 1974. pp. 1446–1451. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kun E, Kearney EB. In: Methods of Enzymatic Analysis. Bergmeyer HU, editor. Vol 4. New York: Academic; 1974. pp. 1802–1806. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellman GL. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rébeillé F, Macherel D, Mouillon JM, Garin J, Douce R. EMBO J. 1997;16:947–957. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]