Tick-borne fever (TBF) caused by the bacterium Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) and transmitted by the tick Ixodes ricinus is a common disease in domestic ruminants on the west coast of southern Norway [8]. TBF in cattle and sheep is characterized by high fever, reduced milk yield, inclusions in circulating neutrophils, leucopenia, abortions and reduced fertility. In cattle, the incubation period after experimental inoculation is 4–9 days and the fever period may last for 1–13 days [6,2]. A. phagocytophilum infection normally gives mild to moderate clinical signs, but serious complications including deaths have been observed [15,5]. Clinical signs in cattle may include depression, decreased appetite, coughing, nasal discharge, respiratory signs, swelling of the hind limbs and stiff gate [6,2]. However, the most serious problem associated with TBF, especially in sheep, is the following immunosuppresion, which may predispose to secondary infections [16]. The infection can therefore cause severe lamb losses on tick pasture [17]. In addition, indirect losses such as reduced growth rate have been observed in both young cattle and lambs infected with A. phagocytophilum [14,11].

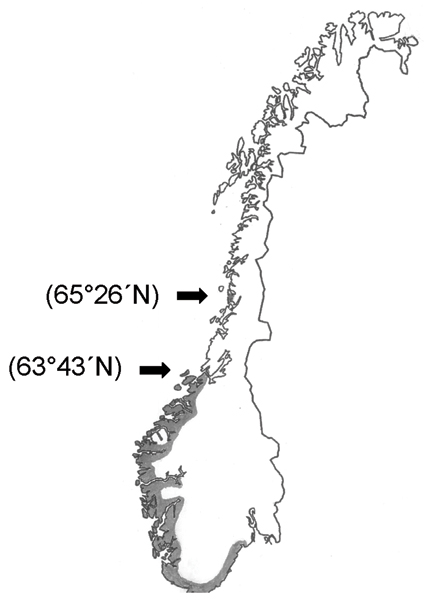

Serological analysis in sheep and wild cervids from southern Norway indicate that A. phagocytophilum infection is abundant on tick-infested pasture [10,12]. The northernmost case of TBF diagnosed so far has been in the county of Sør-Trøndelag (63°43'N) [9], although permanent populations of I. ricinus have been found much further north [4]. Except for Babesia divergens infection in cattle, tick-borne infections in mammalians have not earlier been diagnosed in North Norway [8].

In February 2004, seven pregnant cows were brought from a tick-free area in southern Norway to a farm (Farm A) in Brønnøysund (65°26'N), North Norway, in order to synchronize calving time (Figure 1). The whole flock was turned out on pasture in April/May. Three weeks later four of the purchased animals contracted high fever (40.9–41.2°C) within a period of four days, and two more cows showed high fever one week later. Thus, six of the seven purchased cows reacted with high fever and reduced milk yield. In contrast, clinical signs were not seen in local cattle.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in mammals in Norway (grey area). The latitude for the northern and next most northern case are marked in brackets.

Tick-borne infections were not suspected at that time, and serological testing for antibodies against several respiratory viruses, i.e. bovine coronavirus, bovine parainfluenza virus, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus, and bovine respiratory syncytial virus was inconclusive. Three of these cows became seriously ill and were later euthanasied. Post mortem examination of two cows showed paretic mastitis and endocarditis/polyathritis, respectively, while autopsy of the third cow gave inconclusive results. Unfortunately, no serum or tissue samples were stored for later examination.

In order to replace the lost animals, the farmer received on July 15 three cattle from a farm (Farm B) located in the same municipality as Farm A. The distance between these two farms is around 30 km. Nine days later one of these animals, a three-year-old milking cow, became ill. The most characteristic clinical signs were high fever (>41.0°C), anorexia and a sudden drop in milk yield. No ticks were observed on the cattle. The rectal temperature during the following week varied from 41.2 to 39.5°C. EDTA-blood and whole blood samples were collected on July 30 and a blood smear were prepared and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa. A. phagocytophilum inclusions were detected by light microscopy in 34% of the neutrophils.

In order to investigate if other cattle on Farm A had been exposed to A. phagocytophilum, EDTA and whole blood samples were collected on August 10. The flock size at that time was 15 milking cows and 11 calves. In addition, serum samples from cattle on Farm B were collected (Table 1). This flock consisted of 18 milking cows and 14 calves/heifers.

Table 1.

Blood samples from cattle analyzed for A. phagocytophilum infection by blood smear examination, PCR analyses and specific antibodies in the Brønnøysund area.

| Positive | IFA-antibodies | |||||

| n | Blood smear | PCR | n | positive n (%) | Mean antibody level (log10) ± SD | |

| Farm A | 13 | 1 | 1* | 14 | 14 (100%) | 2.81 ± 0.279** |

| Farm B | - | - | - | 18 | 4 (22%)*** | 1.98 ± 0.391 |

Blood smears were prepared from EDTA-blood and stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa. A total of 400 neutrophils were examined on each smear by light microscopy; the number of cells containing Anaplasma inclusions was recorded, and the percentage of infected neutrophilic granulocytes was calculated. The EDTA-blood was also analysed for A. phagocyophilum infection by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.

Briefly, total genomic DNA was isolated from tissue and blood samples using a commercially available kit (DNeasy Tissue kit; QIAGEN) and the DNA content was measured spectrophotometrically. Samples were subjected to a semi-nested PCR strategy, using primers 16S-F5 (5'-AGTTTGATCATGGTTCAGA-3') and ANA-R4B (5'-CGAACAACGCTTGC-3') for initial amplification of a 507 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene in A. phagocytophilum. The subsequent semi-nested reaction with primers 16S-F5 and ANA-R5 (5'-TCCTCTCAGACCAGCTATA-3') produced a 282 bp fragment. The amplified products of the initial PCR were diluted at 1:100 in distilled water, and 2 μl used as a template in the second reaction. PCR was performed in 25 μl reaction volumes containing 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.7 U AmpliTaq Gold enzyme (Perkin Elmer), and approximately 100 ng of DNA. Cycling parameters were 95°C for 5 min, followed by 3 cycles of 94°C, 55–52°C (touchdown of 1.0°C per cycle), and 72°C for 30 s each, another 35 cycles (25 cycles for the semi-nested reaction) of 94°C, 52°C and 72°C for 30 s each, and finally a 5 min incubation at 72°C.

A. phagocytophilum variants were detected by direct DNA sequence determination of PCR products. The PCR products were sequenced in both directions using Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing chemistry and capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 310 instrument (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were visually inspected from chromatograms.

Serum samples were analysed for antibodies to A. phagocytophilum. Since strong serological cross-reactions between all members of the A. phagocytophilum group have been reported [3], the sera were analysed using an indirect immunofluorescence antibody assay (IFA) with a horse isolate (formerly Ehrlichia equi) as antigen. A titre of 1.6 (log10 reciprocal of 1:40) or more was regarded as positive [1,10].

A total of 13 EDTA-blood samples from 12 cows were collected from Farm A. In addition, 14 and 18 serum samples were analysed from Farm A and B, respectively. Results from blood smear examination, PCR analyses and serology are shown in Table 1. One cow from Farm A was positive by PCR analyses and gene sequencing, i.e. the cow with clinical signs in July. A simultaneous infection with two 16S rRNA gene variants of A. phagocytophilum was found.

Only newly purchased animals on Farm A developed clinical disease. Lack of clinical signs in A. phagocytophilum infected cattle may be due to several factors, including cattle breed resistance, genetic variants of A. phagocytophilum, and acquired immunity. Breed resistance may be excluded since all cows involved belonged to Norwegian Red Cattle. Earlier studies in sheep and cattle indicate that several variants of A. phagocytophilum exist and that these variants may cause different clinical and serological responses [15,13]. The genetic variant(s) involved in cattle on Farm B is, however, unknown.

In the present study, immunity in indigenous cattle may have been acquired through exposure to A. phagocytophilum during previous pasture seasons. Calves and young animals may show no signs of clinical infection, except for a moderate temperature reaction [15]. This immunity may be insufficient to prevent later infection from A. phagocytophilum, but may be sufficient to prevent clinical signs [7].

Serological results in cattle on Farm A indicated a widespread exposure to A. phagocytophilum. Although few ticks were seen on the animals, earlier studies indicate that exposure to the bacterium may be common even on pastures with no apparent tick infestation [11]. It may be mentioned that cases of babesiosis had earlier been observed on this farm.

Serological results indicate that cattle on Farm B were also exposed to A. phagocytophilum, although tick-borne infections have never been observed on this farm. The sensitivity of the serological test could have been increased if a strictly homologous antigen had been used, but such an antigen was unfortunately not available.

Experimental infection studies in cattle showed that specific antibodies to A. phagocytophilum disappeared between 120 and 210 days after initial exposure [5]. In the present case, the infected cow may have been exposed to the bacterium before it arrived at Farm A. However, the incubation period, fever reaction and serological response indicate that the cow had no previous immunity to A. phagocytophilum. Earlier observation indicates that initial exposure on an endemic pasture increases the risk of clinical anaplasmosis [7].

The geographical distribution and clinical aspects of this infection in cattle in Norway are unknown. Three of the seven cows that were brought from southern Norway to Farm A became seriously ill after showing clinical signs of acute A. phagocytophilum infection [15]. Two of these three cattle developed paretic mastitis. Acute mastitis has also earlier been observed in connection with this infection in cattle [15,5]. In the three cases, however, A. phagocytophilum infection could not be confirmed due to lack of samples.

In conclusion, the present study documents that A. phagocytophilum infection exists in North Norway and indicates that the bacterium has been present but unnoticed in the area for years. Further investigation will be needed in order to characterize genetic variants involved in A. phagocytophilum infection in cattle.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the two farmers involved for their collaboration, and Eivind Hermann and Eli Brundtland for technical assistance.

References

- Artursson K, Gunnarsson A, Wikström U-B, Olsson Engvall E. A serological and clinical follow-up in horses with confirmed equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Equine Vet J. 1999;31:473–477. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1999.tb03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun-Hansen H, Grønstøl H, Hardeng F. Experimental infection with Ehrlichia phagocytophila in cattle. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1998;45:307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1998.tb00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumler JS, Asanovich KM, Bakken JS, Richter P, Kimsey R, Madigan JE. Serologic cross-reaction among Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia phagocytophila and human granulocytic Ehrlichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1098–1103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1098-1103.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl R. The distribution and host relations of Norwegian ticks (Acari: Ixodides) Fauna Norv Ser B. 1983;30:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Pusterla N, Braun U. Clinical findings in cows after experimental infection with Ehrlichia phagocytophila. J Vet Med A. 1997;44:385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1997.tb01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusterla N, Huder J, Wolfensberger C, Braun U, Lutz H. Laboratory findings in cows after experimental infection with Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:643–647. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.643-647.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusterla N, Pusterla JB, Braun U, Lutz H. Serological, hematologic, and PCR studies of cattle in an area of Switzerland in which tick-borne fever (caused by Ehrlichia phagocytophila) is endemic. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:325–327. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.3.325-327.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S. Utbredelsen av sjodogg (tick-borne fever) i Norge (The distribution of tick-borne fever (TBF) in Norway) Norsk Vet Tidsskr. 1997;109:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S. Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) infection in sheep and wild ruminants in Norway. A study on clinical manifestation, distribution and persistence. Thesis, Oslo. 2003. p. 132.

- Stuen S, Bergström K. Serological investigation of granulocytic Ehrlichia infection in sheep in Norway. Acta Vet Scand. 2001;42:331–338. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-42-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S, Bergström K, Palmér E. Reduced weight gain due to subclinical Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly Ehrlichia phagocytophila) infection. Exp Appl Acarol. 2002;28:209–215. doi: 10.1023/A:1025350517733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S, Åkerstedt J, Bergström K, Handeland K. Antibodies to granulocytic Ehrlichia in moose, red deer, and roe deer in Norway. J Wildl Dis. 2002;38:1–6. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuen S, Bergström K, Petrovec M, Van de Pol I, Schouls LM. Differences in clinical manifestations and hematological and serological responses after experimental infection with genetic variants of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in sheep. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:692–695. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.4.692-695.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SM, Kenny J. The effects of tick-borne fever (Ehrlichia phagocytophila) on the growth rate of fattening cattle. Brit Vet J. 1980;136:364–370. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(17)32239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi J. Studies in epidemiology of bovine tick-borne fever in Finland and a clinical description of field cases. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1966;44(Suppl 6):66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldehiwet Z, Scott GR. Tick-borne (pasture) fever. In: Woldehiwet Z, Ristic M, editor. Rickettsial and chlamydial diseases of domestic animals. Pergamon Press, Oxford; 1993. pp. 233–254. [Google Scholar]

- Øverås J, Ulvund MJ, Waldeland H, et al. Tap og tapsårsaker i utvalgte saueflokker (Sheep losses and their causes) Norsk Vet Tidsskr. 1985;97:469–475. [Google Scholar]