Abstract

Objectives To compare the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy delivered by telephone with the same therapy given face to face in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder.

Design Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial.

Setting Two psychology outpatient departments in the United Kingdom.

Participants 72 patients with obsessive compulsive disorder.

Intervention 10 weekly sessions of exposure therapy and response prevention delivered by telephone or face to face.

Main outcome measures Yale Brown obsessive compulsive disorder scale, Beck depression inventory, and client satisfaction questionnaire.

Results Difference in the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive disorder checklist score between the two treatments at six months was -0.55 (95% confidence interval -4.26 to 3.15). Patient satisfaction was high for both forms of treatment.

Conclusion The clinical outcome of cognitive behaviour therapy delivered by telephone was equivalent to treatment delivered face to face and similar levels of satisfaction were reported.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN500103984.

Introduction

Obsessive compulsive disorder is a disabling mental health illness that tends to be chronic unless adequately treated.1 The economic burden of this disorder is high—the estimated direct and indirect costs are $8.4m (£4.5m, €6.6m) in the United States each year.2 Cognitive behaviour therapy, particularly graded exposure and response prevention, is effective in treating obsessive compulsive disorder.3 The current mode of delivery is a 45-60 minute face to face session with the therapist each week, during the hours of 9 am and 5 pm. Such a mode of delivery results in long waiting lists and precludes access to treatment. Recent mental health policy in the United Kingdom demands more accessible and effective treatments. Thus, alternative models of delivery have been proposed that aim to reduce contact with therapists and make services more accessible.4 Innovations such as computerised cognitive behaviour therapy and facilitated self help still often require patients to attend scheduled clinic appointments.5,6 Although useful, these systems increase throughput and access only for patients who can attend the clinic. Providing treatment over the telephone could increase access to patients who cannot attend clinic appointments for geographical, social, medical, or economic reasons. Telephone delivery of cognitive behaviour therapy is growing.7-9 A pilot study of telephone delivery of such treatment in obsessive compulsive disorder showed potential with regard to effectiveness and reduced therapist time, and a larger open study found a good outcome.10,11

Methods

Design, objectives, and randomisation

We carried out a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial that compared exposure therapy and response prevention delivered either face to face during traditional 60 minute appointments or by telephone with reduced contact with the therapist. We hypothesised that exposure therapy and response prevention delivered by either of these methods will have similar clinical outcomes in the treatment of obsessive cognitive disorder.

Participants

We recruited patients during 2001 and 2002 from two psychology outpatient treatment units in greater Manchester. All patients were assessed at screening clinics, and patients whose main problem was obsessive compulsive disorder were invited to take part. Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder; obsessive compulsive disorder as the main presenting problem; score of 16 or more on the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive checklist; and age 16-65. We excluded patients who had obsessional slowness (a variant of obsessive compulsive disorder), organic brain disease, a diagnosis of substance misuse, or severe depression with suicidal intent, and patients who had been on a stable dose of antidepressants or anxiolytics for less than three months.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure was the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive checklist (self report version).12 This is a 10 item questionnaire, and each question is scored between 0 and 4 (0 no symptoms, 4 severe symptoms). The total score range is 0-7 very mild, 8-15 mild, 16-23 moderate, 24-31 marked, and 32-40 severe. A secondary outcome measure was the Beck depression inventory.13 Satisfaction with treatment was measured using the client satisfaction questionnaire at the initial follow-up visit.14

Procedure

To establish baseline data we assessed patients twice, with four weeks in between. We used permuted blocks with a block size of four to randomise patients.15 Randomisation sheets were drawn up at the first baseline visit and kept by the principal investigator. Therapists randomised patients to treatment groups four weeks later after telephoning the principal investigator to obtain the treatment allocation. Researchers who were blinded to treatment allocation assessed patients at both of the baseline visits, the initial visit after treatment, and at one, three, and six months of follow-up.

Interventions

Face to face therapy consisted of 10 one hour sessions with the therapist on an individual basis. In the first session the therapist explained the rationale of graded exposure and response prevention, which aims to reduce the patient's anxious and fearful reactions through gradual, repeated exposure to anxiety producing situations. In collaboration with the patient, therapists used the assessment data to devise a hierarchy of fears. From this hierarchy, patients and therapists set weekly targets to be completed between sessions. The therapist encouraged the patient to progress though the hierarchy of fears by practising their targets for at least one hour a day and monitoring their progress on a homework sheet. The therapist reviewed homework, helped devise weekly targets, encouraged the use of a co-therapist (relative or friend), pre-empted difficulties, and helped solve problems.

Telephone therapy consisted of one face to face session with the therapist that covered the same material as the first session of the face to face arm, followed by eight scheduled weekly telephone calls of up to 30 minutes in length. Treatment was the same as in the face to face arm, but it was delivered in a shorter period of time and the therapist sent homework sheets to the patient. The therapist's role was the same as in the face to face arm. The final session consisted of a one hour face to face treatment session.

Treatment was delivered by two trained and experienced cognitive behaviour therapists (one therapist at each site delivered both forms of treatment). Consistency of treatment was maintained by therapist manuals, fortnightly supervision of both therapists (where notes were scrutinised), and training days every four months during the first year of the study.

Sample size and statistical methods

We analysed the data on an intention to treat basis and assumed that missing data were missing at random. Because the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive checklist score would be expected to change over time, we did not use the “last observation carried forward” method to imput data.16,17 To assess non-inferiority of the two treatments, we computed the two sided 95% confidence interval of the difference between treatments.18 Using this method, the experimental treatment is not inferior to the control treatment at a 2.5% level if the upper boundary is below a prespecified margin of non-inferiority,18,19 in this case 5 units on the Yale Brown checklist. With 40 participants in each group (allowing for attrition of eight in each group) and a within group standard deviation of 7.9,20 the study would have 80% power to reject the null hypothesis that telephone therapy is inferior to face to face therapy.21 Adjustment for baseline values of the Yale Brown checklist and Beck depression inventory would be expected to increase power by giving narrow confidence intervals. We used Stata 8 to analyse the data.

Results

Flow of participants, follow-up, and sample characteristics

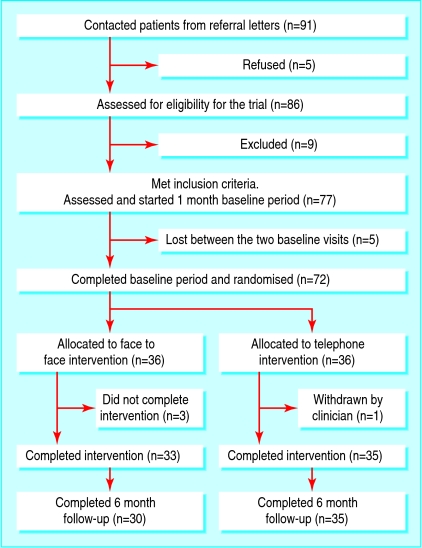

We invited 91 patients to be assessed and five declined (fig 1). Thus, we assessed 86 patients for eligibility and excluded nine (two with a Yale Brown checklist score > 16; two with suicidal intent; one with substance misuse; and four with problems not connected with obsessive compulsive disorder: one health anxiety, two posttraumatic stress disorder, and one social phobia). Five of the 77 patients that we recruited did not attend for baseline assessment. Four of the 72 participants allocated to treatment (36 for each arm) did not complete their treatment (three did not attend appointments and one was withdrawn from the telephone arm owing to increased depression and suicidal ideation deemed by the therapist to warrant a face to face appointment) and three patients were lost to follow-up at six months. Table 1 shows the key baseline characteristics for each group.

Fig 1.

Flow of participants through the trial

Table 1.

Baseline data of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder treated with cognitive behaviour therapy. Values are number (%) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Treatment delivered by telephone (n=36) | Treatment delivered face to face (n=36) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 33.4 (9) | 30.4 (10) |

| Mean duration of obsessive compulsive disorder in years (SD) | 15.3 (11) | 14.9 (11) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Married | 15 (42) | 12 (33) |

| Single, widowed, or divorced | 16 (44) | 15 (42) |

| Cohabiting | 5 (14) | 9 (36) |

| Sex: | ||

| Female | 20 (56%) | 23 (61) |

| Male | 16 (44) | 13 (25) |

| Employment: | ||

| Employed | 25 (69) | 22 (66) |

| Unemployed | 9 (25) | 10 (28) |

| Other | 2 (6) | 4 (11) |

| Treatment site: | ||

| Stockport | 20 (56) | 19 (53) |

| Macclesfield | 16 (44) | 17 (47) |

| Treatment history: | ||

| Past psychological treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder | 14 (39) | 11 (31) |

| Past psychological treatment for other mental health disorder | 14 (39) | 14 (39) |

| Past drug treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder | 19 (53) | 17 (47) |

| Currently taking antidepressants | 22 (61) | 15 (42) |

Clinical outcome

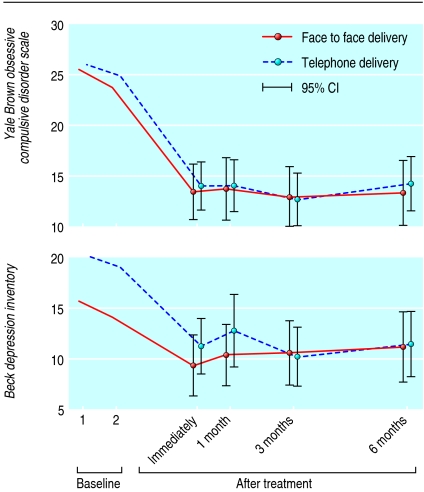

Figure 2 shows the mean scores for the obsessive compulsive disorder and depression scales in the two treatment groups. A mean Yale Brown checklist score of 25 before treatment indicates obsessive compulsive disorder of marked severity. Table 2 gives the mean values for each treatment group. Differences between the two sets of baseline scores for the obsessive compulsive disorder checklist and depression inventory were not statistically significant (mean difference for Yale Brown checklist 1.4 (95% confidence interval 0.32 to 3.13) and for Beck depression inventory 1.3 (1.96 to 4.56)).

Fig 2.

Scores for Yale Brown obsessive compulsive disorder checklist and Beck depression inventory from first baseline visit to six months of follow-up

Table 2.

Main outcome measures and effect of treatment in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder

|

Measure

|

Treatment delivered by telephone

|

Treatment delivered face to face

|

Adjusted*mean difference between treatment groups (95% CI)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | No | Mean (SD) | No | ||

| Yale Brown obsessive compulsive disorder score | |||||

| Before randomisation: | |||||

| 1st baseline visit | 25.9 (4.9) | 36 | 25.5 (5.5) | 36 | |

| 2nd baseline visit | 24.9 (4.7) | 36 | 23.7 (5.8) | 36 | |

| After randomisation: | |||||

| Immediately after treatment | 14 (6.9) | 35 | 13.4 (7.7) | 33 | −0.59 (−3.51 to 2.34) |

| 1 month follow-up visit | 14 (7.3) | 33 | 13.7 (8.5) | 32 | −0.92 (−4.31 to 2.47) |

| 3 month follow-up visit | 12.6 (7.5) | 34 | 12.9 (7.7) | 29 | −1.11 (−4.60 to 2.37) |

| 6 month follow-up visit | 14.2 (7.8) | 35 | 13.3 (8.6) | 30 | −0.55 (−4.26 to 3.15) |

| Beck depression inventory score | |||||

| Before randomisation: | |||||

| 1st baseline visit | 20.2 (10.4) | 36 | 15.7 (8.5) | 36 | |

| 2nd baseline visit | 19.1 (10.6) | 36 | 14.1 (9.1) | 36 | |

| After randomisation: | |||||

| Immediately after treatment | 11.2 (8.0) | 35 | 9.3 (8.5) | 33 | −0.52 (−3.66 to 2.63) |

| 1 month follow-up visit | 12.7 (10.1) | 33 | 10.3 (8.4) | 32 | 0.13 (−4.01 to 4.27) |

| 3 month follow-up visit | 10.1 (8.4) | 34 | 10.6 (8.4) | 29 | −1.79 (−5.65 to 2.08) |

| 6 month follow-up visit | 11.5 (9.5) | 35 | 11.1 (9.1) | 29 | −2.46 (−6.38 to 1.47) |

| Score on client satisfaction questionnaire | |||||

| Immediately after treatment | 28.74 (3.6) | 34 | 29.84 (2.9) | 32 | −0.81 (−2.46 to 0.84) |

Analysis of covariance: adjusted for baseline Beck depression inventory score, baseline Yale Brown obsessive compulsive disorder score, and site.

Clinical outcome at all four time points was equivalent for both treatment arms. At six months of follow-up the adjusted estimate of the effect of treatment was 0.70 (-2.71 to 4.11) for the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive checklist and 1.51 (-2.23 to 5.25) for the Beck depression inventory—a slight reduction in the mean value for telephone compared with face to face delivery. All confidence intervals for the Yale Brown checklist score are within 5 units; this suggests that the treatments are equivalent. Between the start of the treatment and the six month follow-up visit, mean scores on the Yale Brown checklist dropped by about twice the prespecified margin of non-inferiority in both treatment groups.

The data for the Yale Brown obsessive compulsive checklist were less complete at the six month follow-up in the face to face treatment group (30 of 36) than in the telephone group (35 of 36). Patients not followed up at six months had a worse Yale Brown checklist score at the assessment immediately after treatment (mean 21, SD 3.5, n = 3) than those who were followed to six months (mean 13.4, SD 7.2, n = 65) (P = 0.07). This suggests that the mean Yale Brown checklist score at six months may be slightly underestimated for the face to face treatment group.

Treatment was deemed clinically relevant if the mean pretreatment score was reduced by two standard deviations or more after treatment.22 Treatment was clinically relevant in 49 patients (72%)—27 (77%) patients in the telephone treatment arm and 22 (67%) in the face to face treatment arm.

Satisfaction

Total scores on the client satisfaction questionnaire ranged from 0 to 32 (higher score indicates greater satisfaction). Patients were very satisfied with treatment, and the results were similar for both treatments (table 2).

Blindness

We assessed the level of blindness of the independent assessor by asking them to guess the patients' treatment status at one month of follow-up. Nine of the 72 patients directly or indirectly revealed their treatment status to the assessor. The assessors guessed 35 (56%) of the remaining 63 correctly and 28 (44%) incorrectly.

Discussion

The clinical outcome of cognitive behaviour therapy delivered by telephone was equivalent to treatment delivered face to face at all four follow-up time points and patients reported similarly high levels of satisfaction. The effect size of treatment was 2.5, which is as large or larger than other studies of face to face (individual or group) cognitive behaviour therapy in obsessive compulsive disorder.3

Comparison with other studies

The characteristics of our patients (age, sex, current use of antidepressants, and duration of obsessive compulsive disorder) are similar to other studies on this disorder.23-25 Yale Brown checklist scores before and after treatment are also similar to other studies that have used exposure on its own or as part of a cognitive behavioural intervention.20,23,24 Sample size in our study is equal to or greater than most other studies of cognitive behaviour therapy in this disorder.23-25 The attrition rate in our study was low compared with other studies; this contrasts with reports that patients with obsessive compulsive disorder often refuse exposure treatment.25 Only one patient was lost from the telephone arm of the trial. Reasons for the low attrition rate in both treatment arms are unclear. Both clinics had long waiting lists (12 months or more), so perhaps the participants were all highly motivated. It is also possible that the experienced therapists were particularly good at engaging patients.

Implications

Telephone sessions were 30 minutes (50%) shorter than face to face sessions; this equates to more than a 40% saving in the therapist's time. This has important economic implications. Our findings support the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for obsessive compulsive disorder,3 which encourage cognitive behaviour therapy delivered by telephone.

Limitations

We did not include a control (no treatment) group. However, we found no differences between the two sets of baseline scores so few improvements were made in the absence of treatment. This finding is consistent with other studies.26,27 We did not compare treatment with another psychological intervention. However, other studies that have used interventions not based on cognitive behaviour therapy, such as relaxation and anxiety management, have shown poor results.23,28 Patients in our study were followed up for six months only, which precludes conclusions on the long term efficacy of telephone treatment. Finally, our findings may only be relevant to settings in which patients are treated by experienced therapists in departments that specialise in cognitive behaviour therapy. Further investigations are needed into the acceptability by clinicians of delivering treatment by telephone.

What is already known on this topic

Cognitive behaviour therapy delivered by telephone may offer help to people with obsessive compulsive disorder

What this study adds

Telephone delivery of cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder results in equivalent clinical outcome and similar levels of patient satisfaction as traditionally delivered face to face approaches

This form of treatment delivery is an accessible intervention that can reduce costs and therapist time

Contributors: KL conceived and designed the study, obtained funding, drafted the manuscript, and is guarantor. DC, DR, and RG helped conduct the study. CR helped design the study and analyse the data. GH helped design the study. SH and CJ helped interpret and analyse the data. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding: NHS Executive North West (Research and Development Fund).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: South Cheshire local research committee M125/01; Stockport ethics committee RJC/SPR/1809.

References

- 1.Marks IM. Fears, phobias and rituals: panic anxiety, and their disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- 2.Dupont RL, Rice DP, Shiraki S, Rowland CR. Economic costs of obsessive compulsive disorder. Med Interface 1995;8: 102-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Obsessive compulsive disorder. Clinical guideline 31. www.nice.org.uk/CG031 (last accessed 18 Aug 2006).

- 4.Lovell K, Richards DA. Multiple access points and levels of entry (MAPLE): ensuring choice, acceptability and equity for CBT services. Behav Cogn Psychother 2000;28: 379-91. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Beverley C. Computerized cognitive behaviour therapy: a systematic review. Behav Cogn Psychother 2004;32: 31-55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Den Boer PCAM, Wiersma D, Van Den Bosch RJ. Why is self-help neglected in the treatment of emotional disorders? A meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2004;34: 959-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr DC, Lokosky W, Bertagnoli A, Goodkin DE, Wende J, Dwyer P, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis disorder. J Clin Consult Psychol 2000;68: 356-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer RL, Birchall H, McGrain L, Sullivan V. Self-help for bulimic disorders: a randomised controlled trial comparing minimal guidance with face-to-face or telephone guidance. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181: 230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNamee G, O'Sullivan G, Lelliott P, Marks I. Telephone-guided treatment for housebound agoraphobics with panic disorder: exposure vs relaxation. Behav Ther 1989;20: 491-7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovell K, Fullalove L, Garvey R, Brooker C. Telephone treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Cogn Psychother 2000;28: 87-91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor S, Thordarson DS, Spring T, Yeh AH, Corcoran KM, Eugster K, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2003;32: 13-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman WK, Ramussen SA, Price LH, Mazure C, Henninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale: development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46: 1006-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4: 561-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attkinson C, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire: psychometric properties and correlations with service utilisation and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Planning 2003;5: 233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pocock S. Clinical trials. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 1990.

- 16.Lavori PW. Clinical trials in psychiatry: should protocol deviation censor patient data? Quality of life assessment in clinical trials: methodolocigal issues. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992;6: 29-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shrout PE. Clinical trials in psychiatry: a comment. Quality of life assessment in clinical trials: methodological issue. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992;6: 49-50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis A, Ebbutt AF. Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. BMJ 1996;313: 36-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Wang SJW. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence of randomized trials. JAMA 2006;295: 1152-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Balkom AJ, De Haan E, Van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KAL, Van Dyck R. Cognitive and behavioural therapies alone versus in combination with fluvoxamine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Nervous Ment Dis 1998;186: 492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elashoff JD. nQuery advisor version 5.0 user's guide. Los Angeles, CA, 2002.

- 22.Jacobsen NS, Traux P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59: 12-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindsay M, Crino R, Andrews G. Controlled trial of exposure and response prevention in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171: 135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordioli AV, Heldt E, Bochi DB, Margis R, Basso de Sousa M, Tonello JF, et al. Cognitive-behavior group therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Psychother Psychosomat 2003;72: 211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogel PA, Stiles TC, Gotestam KG. Adding cognitive therapy elements to exposure therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: a controlled study. Behav Cogn Psychother 2004;32: 275-90. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor K, Todorov C, Robillard S, Borgeat F, Brault M. Cognitive-behaviour therapy and medication in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder; a controlled study. Can J Psychiatry 1999;44: 64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones MK, Menzies RG. Danger ideation reduction (DIRT) for obsessive compulsive washers: a controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 1998;36: 959-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fals-Stewart W, Marks A, Schafer J. A comparison of behavioural group therapy and individual behaviour therapy in treating obsessive compulsive disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993;181: 189-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]