Measles has reappeared in the United Kingdom, with 449 confirmed cases to the end of May 2006 compared with 77 in 2005, and the first death since 1992.1,2 Cases are occurring in inadequately vaccinated children and in young adults, leading to concerns that endemic measles could re-emerge. But, as with smallpox, measles could be eradicated. It has been eliminated in the Americas since 2002. The World Health Organization has set 2010 as the target for elimination in the European region, where 29 000 cases were reported in 2004.3 Much ground will have to be regained in the United Kingdom if the 2010 target is to be met.

We review the uptake of the combined measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine in the United Kingdom and Europe, and identify susceptible groups. As clinical experience of measles has declined, doctors in the United Kingdom may not consider the diagnosis nor recognise a case. We also therefore consider the diagnosis, management, and control of measles infection.

Measles epidemiology and transmission

Measles is caused by a single stranded RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus from the paramyxovirus family.4 It is among the most contagious of diseases,5 with a basic reproductive number (R0) of 15-20 (box 1).6 The virus remains transmissible in the air or on infected surfaces for up to two hours, obviating the need for direct person to person contact.5,7 Although genetic drift of the viral RNA is documented,4 measles has only one serotype, and both infection with wild type virus and appropriate immunisation confer longstanding immunity.7 Despite this, measles remains a leading cause of vaccine preventable death worldwide. In 2004 an estimated 454 000 deaths were due to measles.5 Mortality from measles is highest in children aged less than 12 months8 and in the developing world.5

Measles vaccine does not reliably induce immunity in the presence of maternal measles antibody, achieving low rates of seroconversion in children aged less than 12 months. Vaccine efficacy increases to over 90% in the 12-15 months age group.8,10 Thus a trade-off exists between vaccinating early and achieving good levels of immunity. Even with 100% coverage, a single dose schedule allows the gradual accumulation of a pool of susceptible people. A second dose, however, reliably leaves about 99% of those vaccinated immune.10 Because measles is so highly infectious, vaccination of 90-95% of the population with a two dose schedule is required to attain an effective reproductive number of less than 1, and thereby halt the endemic transmission of measles.5,11

Summary points

Measles is again a cause for concern in the United Kingdom, with localised outbreaks occurring especially in communities with lower uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination

Measles should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients of all ages with fever and maculopapular rash

Measles is more severe in infants, adults, and those with compromised immunity

Measles may present without fever or rash in immunocompromised people weeks or months after exposure

Vaccination levels across Europe must be improved and maintained to achieve the goal of measles elimination and to prevent re-emergence of endemic measles

Can measles be eradicated?

In addition to smallpox and polio, measles is one of the few virus infections for which eradication is a feasible goal (box 2). Despite vaccination programmes throughout Europe, measles still remains a major problem, with over 29 000 cases reported in the WHO European region in 2004.3 The Americas were declared free from endemic measles transmission in 2002,3 w2 but cases still occur as a result of importation from other countries, with over a third of US cases linked to Europe.3 w3 Similarly imported cases in the European Union often originate in other European countries.3,12 The WHO Europe strategic plan 2005-10 sets the goal for interruption of endemic measles transmission.3

Sources and selection criteria

We carried out a search of PubMed using the terms “epidemiology”, “surveillance”, “epidemic”, “outbreak”, “diagnosis”, “complications”, “symptoms”, “immunosuppression”, and “pregnancy” in conjunction with measles

For clinical guidelines we accessed websites of the UK Health Protection Agency, UK Department of Health, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and WHO

We also consulted several formal virology texts

Measles in the United Kingdom

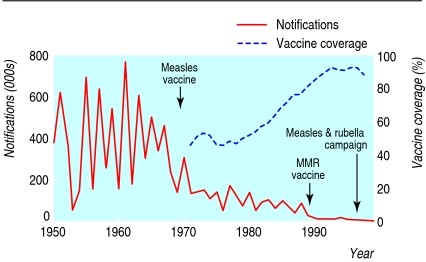

Measles has been a notifiable disease in England and Wales since 1940. In the era before vaccine, cases peaked every 2-3 years, with on average 100 deaths annually.8 Routine immunisation of children with one dose of the single measles vaccine started in 1968,8 with only moderate uptake. This was replaced in 1988 by immunisation against measles, mumps, and rubella, and supplemented by a programme of measles and rubella immunisation of school age children and young people (5-16 year olds) in 1994, to avert an impending measles epidemic.13 By 1995 uptake of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination exceeded 90%. The preschool MMR booster dose was introduced in 1996. Increasing vaccination coverage was mirrored by a fall in notifications from around half a million cases annually in the 1960s and culminated in the interruption of endemic measles transmission (fig 1).12

Fig 1.

Annual measles notifications and vaccine coverage in England and Wales 1950-99w4

In the late 1990s controversy over the safety of the MMR vaccine contributed to declining uptake. Coverage with a first dose reached a nadir of 80% among 2 year olds in England in 2003-4. Accordingly the effective reproductive number for measles rose from 0.47 (1995-8) to 0.82 (1999-2000), raising the likelihood of outbreaks.14 The renewed threat of endemic measles in London, where in some areas as many as 44% of preschool children and 22% of primary school children were susceptible,15 prompted the 2004-5 MMR Capital Catch-up Campaign. Although vaccination rates in 2 year olds in the United Kingdom have begun to recover,w5 uptake still falls short of requirements, and recent years have seen an accumulation of a substantial pool of the susceptible people required to sustain an outbreak.

Box 1 Terminology for transmission of infection3,9 w1

Basic reproductive number (R0)

Average number of secondary infections resulting from each index case in a fully susceptible population. Measure of transmissibility of an infection

Effective reproductive number (R)

Number of secondary cases resulting from an average index case in a partially immune population. Determined by the fraction of the population that is non-immune and the transmissibility of the infection

Endemic transmission

Existence of a continuous indigenous chain of transmission that persists for more than one year in any defined geographical area. This occurs when the effective reproductive number is greater than 1

Elimination

Defined by WHO as an incidence of fewer than 1 case per million population in a given region

Interruption of endemic transmission

Equivalent to elimination from a geographical region. It occurs when the effective reproductive number is less than 1

Eradication

Worldwide elimination

Box 2 Characteristics of eradicable viral diseases

The virus has no animal reservoir

Chronic infection does not occur or people who are persistently infected are not infectious to others

The virus is genetically stable over time

The infection can be easily and reliably diagnosed

A safe and effective vaccine is available

Susceptible groups in the United Kingdom include:

Unvaccinated children, including those in marginalised communities—for example, travelling families with reduced access to health care2

Young adults born in the United Kingdom between 1970 and 1979, when coverage with single measles vaccine was suboptimal and exposure to the natural disease was on the wane8

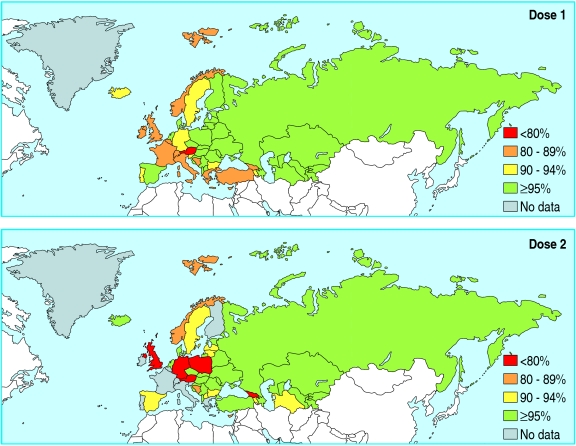

Young adults from Europe and other countries where measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination was introduced at various times and with variable uptake may likewise be unprotected (table 1). In some European countries, coverage levels of greater than 90% have never been achieved so that younger age groups are also at risk (fig 2). Overall, 23-43% of cases in recent outbreaks in the United Kingdom have been associated with importation from countries where measles is still circulating12

Recipients of a single dose of measles containing vaccine

Children aged less than 12 months who have not yet been vaccinated

Immunocompromised people in whom live vaccines are contraindicated16

Table 1.

National immunisation coverage reported as percentage of target population vaccinated with first dose measles containing vaccine in selected WHO European region member states 1980-2005 (also see bmj.com)w6

| Country | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | — | 40 | 60 | 60 | 75 | 75 |

| Belgium | — | — | 85 | 85 | 82 | 88 |

| Croatia | — | — | — | 92 | 93 | 96 |

| Cyprus | 29 | — | — | 83 | 86 | 86 |

| Czech Republic | — | — | — | 96 | — | — |

| Finland | — | — | 97 | 98 | 96 | 97 |

| France | — | 35 | 71 | 83 | 84 | — |

| Germany | — | 25 | 50 | 75 | 92 | 93 |

| Greece | — | 77 | 76 | 70 | — | — |

| Ireland | — | 63 | — | — | — | 84 |

| Italy | — | 12 | 43 | 50 | — | 87 |

| Netherlands | 91 | 92 | 94 | 94 | — | 96 |

| Poland | 92 | 92 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 |

| Portugal | 54 | 70 | 85 | 94 | 87 | 93 |

| Spain | — | 79 | 97 | 90 | 94 | 97 |

| Switzerland | — | — | 90 | — | — | 82 |

| Turkey | 27 | — | 67 | 65 | 81 | 91 |

| United Kingdom | — | — | 89 | 92 | 88 | 82 |

Fig 2.

Measles containing vaccine (doses 1 and 2) coverage by WHO European region member states for 20043

Clinical manifestations

Measles has an average incubation period of 14 days17 (range 6-19 days)w7 from exposure to onset of rash. The patient is infectious from four days before to four days after the onset of the rash.5 The prodrome lasts 2-4 days and is characterised by fever, malaise, and anorexia. Patients typically look sick and may be wretched, with worsening cough, coryza, congestion, conjunctivitis, lacrimation, and photophobia (box 3).7 w9 Pathognomonic bright red spots with a bluish white speck at the centre (Koplik's spots) are visible on the buccal mucosa opposite the second molar teeth in 60-70% of patients during the prodrome and for up to two or three days after the onset of the rash.4,18

The red maculopapular rash appears first on the hairline and behind the ears, spreading to affect the face then proceeding downwards and outwards to the trunk and the extremities, becoming confluent in places. Generalised lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly may occur.6 The rash begins to fade after three or four days, clearing initially on the skin first affected and leaving behind a brownish discoloration sometimes accompanied by fine desquamation.4,7 In uncomplicated measles clinical recovery begins soon after the appearance of the rash.6 Although the case definition can help identify cases for notification, clinical diagnosis is unreliable and laboratory confirmation is mandatory.

Complications of measles

Complication rates vary by age, geographical region, and outbreak and are increased by immune deficiency, malnutrition, vitamin A deficiency, and intense exposure to measles through household contacts and overcrowding (table 2).19 Mortality is highest in children aged less than 12 months and lowest in 1-9 year olds. Complication rates and mortality then rise into adulthood.8

Table 2.

| Complication | Frequency in developed countries | Susceptible hosts |

|---|---|---|

| Otitis media | 7-9% | Children aged less than 2 years |

| Laryngotracheobronchitis | Children aged less than 2 years | |

| Pneumonia | 1-6% | |

| Diarrhoea | 8% | |

| Hepatitis | 56-66% in adults, rare in children | Adults |

| Febrille seizures | 0.5% | Children |

| Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis | 1 in 1000 cases | |

| Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis | 1 in 25 000 cases (all ages) | Post measles aged under 2 years (1 in 8000 cases) |

| Measles inclusion body encephalitis | Rare | Immunocompromised |

| Giant cell pneumonitis | Rare | Immunocompromised |

| Blindness | Rare (common in developing countries) | Vitamin A deficient |

| Death | 1 per 5000 in United Kingdom |

As a result of vaccination in childhood, people who remain susceptible are now infected at an older average age.9 Paradoxically, as Europe approaches the goal for elimination of measles, a larger proportion of cases occur in adults, in whom complications occur more often and may be more severe.

Respiratory complications

Pneumonia accounts for 56-86% of measles associated deaths.19 Pneumonia may be due to measles or result from superinfection with bacteria or other viruses.6 Giant cell pneumonitis in immunocompromised patients presents with increasing respiratory insufficiency two or three weeks after measles infection.7

Box 3 Clinical case definition of measles from the Centers for Disease Control and Preventionw8

Measles is characterised by a generalised rash lasting greater than or equal to three days and temperature greater than or equal to 38.3°C and the presence of cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis

Clinical vignette

A 32 year old man from mainland Europe was admitted with a one week history of vomiting, diarrhoea, and coryzal symptoms. He was febrile (40°C) and appeared sick and depressed, with bilateral conjunctival injection and a generalised maculopapular rash. He also had hepatitis (alanine aminotransferase 365 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 246 U/l, bilirubin 11 μmol/l). Diagnosis was confirmed by detection of serum measles IgM

Neurological complications

Thirty per cent of patients without symptoms of cerebral involvement have cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis.w10 Electroencephalographic abnormalities are seen in up to 50% of patients.w10 Measles is associated with three distinct encephalitic diseases (table 3).

Table 3.

Measles encephalitides

| Encephalitic disease | Health state of host | Incidence | Typical age at measles infection | Interval to neurological presentation | Time course | Measles virus in cerebrospinal fluid (brain tissue) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis | Normal | 1:1000 | >2 years | Within two weeks of onset of rash | Monophasic (weeks) | No (no) | 15% fatal; 20-40% sequelae |

| Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis | Normal | 1:25 000 | <2 years | 6-8 years | Progressive (years) | No (nucleocapsids but not infectious virus) | 100% fatal |

| Measles inclusion body encephalitis | Immunocompromised | ? | Any age | 1-7 months after exposure | Progressive (months) | No (nucleocapsids but not infectious virus) | 76-85% fatal; 15% sequelae |

Adapted from Griffin DE. In: Knipe DE, Howley PM, eds. Field's virology, 20016 with permission from Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins.

Gastrointestinal complications

Diarrhoea during measles may also be associated with secondary bacterial or protozoal infections, compounding nutritional deficiency in malnourished populations.6 Clinical hepatitis and asymptomatic hypocalcaemia may occur and are seen more often in adults than in children.20 w11 w12

Vitamin A deficiency and blindness

Serum retinol concentrations are depressed during acute measles infection.w13 Measles is the most important cause of blindness in children in populations with borderline vitamin A status, precipitating frank vitamin A deficiency manifest as xerophthalmia.w14 In the developing world, administration of vitamin A during acute measles decreases morbidity and mortality by 50%.21 WHO recommends that high dose vitamin A be used for all children in countries where the case fatality rate is 1% or more.5

Measles induced immune suppression

Infection with measles virus induces transient immunodeficiency.6 The number of circulating T cells is decreased and there is often a striking leucopenia during acute infection.4,6,22 Production of antibody and cellular immune responses to new antigens are impaired and delayed type hypersensitivity responses are inhibited.7 Infants aged less than 1 year and adults show delayed recovery from lymphopenia.22 Immunodeficiency persists for many weeks after lymphocyte counts have returned to normal, and probably accounts for the high all cause mortality worldwide after acute measles.7

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of measles has a low positive predictive value in settings such as the United Kingdom where the incidence is low.23 w15 Laboratory testing is required to confirm the diagnosis and to guide public health management (box 4).23 w15 Suitable samples should also be strain typed to track the circulation and importation of measles.w16 In the United Kingdom, notification triggers the dispatch of an oral fluid testing kit for sample collection by the patient, parent, or general practitioner.12

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of fever and maculopapular rash include rubella, parvovirus B19, enterovirus, scarlet fever, human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, Kawasaki's disease, meningococcaemia, toxic shock syndrome, dengue, HIV, secondary syphilis, and drug eruptions.

Measles in the immunocompromised host

In patients with deficient cellular immunity, measles often presents as a non-specific illness without the typical rash, thereby eluding diagnosis.4,24 w17 Severe complications of measles may occur in up to 80% of immunocompromised hosts, with case fatality rates of up to 70% in patients with cancer and 5-40% in HIV infected patients.24,25

Measles in pregnancy

Measles may be serious in pregnant women, who may develop potentially fatal pneumonitis.4,6 Infection isassociated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, and low birthweight babies.4 Measles is not known to cause congenital malformations.26

Box 4 Laboratory diagnosis of measles

Salivary swab for measles specific IgM taken within six weeks of onset23 or

Serum sample for measles specific IgM taken within six weeks of onset23 or

RNA detection in salivary swabs or other samples13

Classically

Acute (1-7 days after the rash) and convalescent (10-20 days later) serum samples for measles specific IgG, showing a fourfold rise in titre

Atypical measles

An atypical form of severe measles with prolonged fever, unusual skin lesions, severe pneumonitis, pleural effusions, and oedema may be seen in patients who received killed measles vaccine in the United States and Europe in the 1960s.17

Treatment

Uncomplicated measles in immunocompetent people is usually self limiting.7 Antibiotics should be considered for the treatment of possible secondary infections. Children should be excluded from school for five days after the onset of the rash.w7

Prevention

Indications for vaccination are summarised in box 5. All susceptible people should be protected from measles regardless of age, and the need for protection from mumps or rubella should also be considered. In general, those born before 1970 are likely to have had measles, but there is no upper age limit for vaccination. Importantly, there are no safety concerns about giving MMR vaccine to immune people. Vaccine viruses are not transmitted and do not pose a threat to susceptible contacts. Indeed, efforts should be made to minimise the risk of exposure of immunocompromised people to measles by appropriate immunisation of any unprotected household contacts or other close contacts..

Box 5 Indications and contraindications for measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination

Indications8

Children aged 12-15 months, followed by a preschool booster given as soon as three months after the first dose

Older children and adults who have not already received two doses and who may not be protected (for example, born after 1970) should receive one or two doses as required. The second dose should ideally be given after three months, but can be given at any subsequent time

HIV positive people who are not severely immunocompromised

When protection is urgently required the second dose can be given one month after the first. But in a child aged less than 18 months at the time of the second dose, a third preschool dose is recommended

Contraindications16

Pregnant women

Immunocompromised people

Those who have had a confirmed anaphylactic reaction to any of the viral vaccine components or to neomycin or gelatin

Box 6 Post-exposure prophylaxis

MMR vaccine8

MMR vaccine may be effective if given within 72 hours of exposure to susceptible people more than 9 months of age. Note that a first dose given before 12 months does not count towards the two dose schedule

Human normal immunoglobulin prophylaxis8

Prophylaxis with human normal immunoglobulin should be considered within five days of exposure for:

Severely immunocompromised patients

Pregnant women negative for measles IgG

Children aged less than 9 months

Susceptible people who have been exposed to measles may be protected by measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination within 72 hours of exposure, as vaccine induced measles antibody develops more rapidly than natural antibody. Human normal immunoglobulin may be used for post-exposure prophylaxis in vulnerable patient groups in whom MMR vaccine is contraindicated (box 6).

Conclusion

The United Kingdom is experiencing an upsurge in measles cases, with the first reported death since 1992. Localised outbreaks are occurring among unvaccinated children and adults, sometimes initiated by an imported case from Europe or elsewhere. Measles in adolescents or adults can be moderately severe. Infants aged less than 12 months and the increasing population of immunocompromised people are at particular risk as a result of the gaps in herd immunity. In 2006 measles again needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of fever and generalised maculopapular rash and as a possible cause of deteriorating health in immunocompromised patients. The renewed threat of endemic measles highlights the need to achieve and maintain high levels of vaccination coverage throughout Europe if the 2010 goal for elimination is to be met.

Tips for general practitioners

Any patient thought to be susceptible to measles should be offered measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination unless contraindicated

Measles is highly infectious and may be transmitted from four days before to four days after the onset of the rash

MMR vaccine may be used as post-exposure prophylaxis within 72 hours of exposure except when contraindicated

Post-exposure prophylaxis with human normal immunoglobulin within five days of exposure should be considered when the contact is immunocompromised, less than 9 months old, or both seronegative and pregnant

Every suspected case of measles should be notified. Clinical diagnosis is not reliable and it is therefore essential to return the oral fluid sample for laboratory confirmation

Additional educational resources

World Health Organization (www.who.int/topics/measles/en)—includes links to mortality burdens from measles worldwide, clinical features of infection, elimination, and surveillance goals

Health Protection Agency (www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/measles/menu.htm)—general information on measles and epidemiology of measles in the United Kingdom

US Centers for Disease Control (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/submenus/sub_measles.htm)—information on measles and measles epidemiology and surveillance in the United States

Information for patients

NHS immunisation information. MMR the facts (www.mmrthefacts.nhs.uk/)—information on measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination

Supplementary Material

References w1-w17 and a longer table of uptake of MMR vaccine by WHO European region member states are on bmj.com

References w1-w17 and a longer table of uptake of MMR vaccine by WHO European region member states are on bmj.com

We thank Alice Gem for secretarial help with this manuscript.

Contributors: PA did the literature searches. PA and EMM wrote the manuscript. EMM is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: EMM has received sponsorship from Aventis Pasteur MSD towards attending conferences in the past five years.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Health Protection Agency. Measles cases so far in 2006. Press statement dated 15 June 2006. www.hpa.org.uk/hpa/news/articles/press_releases/2006/060615_measles.htm (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 2.Health Protection Agency. Increase in measles cases in 2006, in England and Wales. Commun Dis Rep Wkly 2006;16:3. www.hpa.org.uk/cdr/archives/2006/cdr1206.pdf (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 3.World Health Organization Europe. Eliminating measles and rubella and preventing congenital rubella infection. WHO European region strategic plan 2005-2010. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2005:1-34. www.euro.who.int/document/E87772.pdf (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 4.Gershon AA. Measles virus (rubeola). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone, 2005: 2031-8.

- 5.World Health Organization Media Centre. Fact sheet No 286 revised March 2006. Measles. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs286/en/print.html (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 6.Griffin DE. Measles virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins, 2001;1: 1401-41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shneider-Schaulies S, ter Meulen V. Measles. In: Zuckerman AJ, Banatvala JE, Pattison JR, Griffiths PD, Schoub BD, eds. Principles and practice of clinical virology. 5th ed. Chichester: Wiley, 2004: 399-426.

- 8.Department of Health. Measles. In: Immunisation against infectious disease. 2005:1-24. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/12/44/88/04124488.pdf (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 9.Anderson RM, May RM. Immunisation and herd immunity. Lancet 1990;335: 641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meissner HC, Strebel PM, Orenstein WA. Measles vaccines and the potential for worldwide eradication of measles. Pediatrics 2004;114: 1065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Agency. Measles website. www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/measles/menu.htm (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 12.Ramsay ME, Jin L, White J, Litton P, Cohen B, Brown D. The elimination of indigenous measles transmission in England and Wales. J Infect Dis 2003;187: S198-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vyse AJ, Gay NJ, White JM, Ramsay ME, Brown DW, Cohen BJ, et al. Evolution of surveillance of measles, mumps, and rubella in England and Wales: providing the platform for evidence-based vaccination policy. Epidemiol Rev 2002;24: 125-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen VA, Stollenwerk N, Jensen HJ, Ramsay ME, Edmunds WJ, Rhodes CJ. Measles outbreaks in a population with declining vaccine uptake. Science 2003;301: 804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gay N, Ramsay M. Potential for measles transmission in London. London: Health Protection Agency Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, 2004: 1-5.

- 16.Department of Health. Contraindications and special considerations. In: Immunisation against infectious disease. 2006:1-7. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/12/86/07/04128607.pdf (accessed 29 Jun 2006).

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Infection National Immunization Programme. Measles. In: Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. The pink book. Updated 9th ed. Waldorf, USA: Public Health Foundation, 2006:125-44. www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/pink/meas.pdf (accessed 21 Jun 2006).

- 18.Perry RT, Halsey NA. The clinical significance of measles: a review. J Infect Dis 2004;189: S4-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duke T, Mgone CS. Measles: not just another viral exanthem. Lancet 2003;361: 763-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shalev-Zimels H, Weizman Z, Lotan C, Gavish D, Ackerman Z, Morag A. Extent of measles hepatitis in various ages. Hepatology 1988;8: 1138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussey GD, Klein M. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin A in children with severe measles. N Engl J Med 1990;323: 160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada H, Kobune F, Sato TA, Kohama T, Takeuchi Y, Abe T, et al. Extensive lymphopaenia due to apoptosis of uninfected lymphocytes in acute measles patients. Arch Virol 2000;145: 905-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown DWG, Ramsay MEB, Richards AF, Miller E. Salivary diagnosis of measles: a study of notified cases in the United Kingdom, 1991-3. BMJ 1994;308: 1015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, McCarthy CA. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA 1992;267: 1237-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss WJ, Monze M, Ryon JJ, Quinn TC, Griffin DE, Cutts F. Prospective study of measles in hospitalized, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected children in Zambia. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35: 189-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel M. Congenital malformations following chickenpox, measles, mumps and hepatitis. Results of a cohort study. JAMA 1973;226: 1521-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.